Introduction

The words crisis, life-changing, disruptive and transformative are oft-repeated terms used to describe the effect of the pandemic on education and learning. According to UNESCO, on “1 April 2020, schools and higher education institutions (HEIs) were closed in 185 countries, affecting 1,542,412,000 learners, which constitute 89.4% of total enrolled learners.”1 These worldwide statistics include learners in pre-primary, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels of education, demonstrating the widespread impact of closures across the education industry. There is an urgent need in trying to understand the effects of this disruption to education, both in the now and in the future and this can be seen in the growing number of articles and publications since last year—in Singapore for example, the National Institute of Education (NIE) webpage “Education Related Covid-19 Articles”2 has over a hundred articles. The abstracts on the website show that some articles address the sudden changes that students and teachers have had to face in switching from classroom teaching to online or blended teaching while other articles offer practical tips for educators and parents. A third category of articles is more forward-thinking, and predicts that this rupture will, in fact, act as catalyst for positive change in educational methodologies.3 While many countries had to shut down schools and colleges completely, in Singapore, after a brief period of completely online interaction, we have been relatively lucky to be able to resume face-to-face classes from September 2021 albeit, with some restrictions. Since March 2020, my classroom experience has included various permutations and combinations of online and face-to-face teaching. The classes that I taught in this time period are all within the purview of contextual studies,4 which include supervising final year students during their dissertation. Building on the global scholarship that is being produced about the impact of COVID-19 on education, this paper offers a study of my teaching experience at LASALLE College of the Arts since the advent of COVID-19 in March last year.

In what follows, I reflect on how this disruption has transformed the ways in which coursework is planned and executed, the lessons learnt through coping with these unprecedented changes and to examine the suitability of the innovations made as a response to disruption. This reflective process will show that periodic reflection of our own practice, be it in the classroom or on the stage, is an important mindset to have as theatre educators whether during disruptive times or otherwise.

The Background

My entire teaching experience prior to COVID-19 was in teaching students face-to-face and therefore it was a steep learning curve to acclimatise to remote teaching. To help in this reflective process, I researched online teaching and the creation of curriculum for online teaching hoping to find a framework of reference. In one of the books that I read, The Online Teaching Survival Guide by Boettcher and Conrad, the authors provide a table to explain different types of courses which provided a framework for my teaching experiences.5 The table is presented below.

Types of Courses | ||

Proportion of Content Delivery Online | Type of Course | Description |

None | Traditional – Face-to-Face | No online technology. |

1 – 29% | Web facilitated | Web-based technology used to facilitate what is essentially a face to face course – usually a course management system or a website to post syllabus and assignments. |

30 – 79% | Blended / Hybrid | A blend of online and face to face delivery. Most of the content is delivered online, typically using online discussions with some face to face meetings. |

80% or more | Online | Most or all of the content is delivered online. Typically has no face to face meetings. |

Table 1 Description of different types of courses. Adapted from Boettcher and Conrad6

I have been teaching part-time in LASALLE since 2007 and over the years I have taught both diploma and BA students a variety of subjects. The curriculum has, of course, changed many times over these years and the ways in which the classes have been structured and delivered have a large part to do with the different Programme Leaders and their vision for the courses. Despite the many changes, what has been consistent through the years is that all the courses were a combination of traditional face-to-face and web facilitated courses as described in the first two types of delivery shown in the table above. It is only after the disruption of COVID-19 that we experienced the other two types—the blended/hybrid and the fully online courses—which I will address later in this paper.

Disruption:

Reactions and Responses to the Changes Caused by the Pandemic

Phase 1 – March 20207

The courses that I taught till March 2020 had a clearly established rhythm that was thrown into disarray by COVID-19. The response to the first break in rhythm was perforce reactive rather than proactive. The first wave of disruptions we had to manage was the reduced class sizes when we were told at times to split the class into two groups. The first attempt was to have the two groups in two different rooms at the same time and teach one group face-to-face while the other group would watch this on a screen facilitated by Zoom. While this worked for the group in class with the lecturer, the other group tended to get distracted and switch off. As an educator, I found this highly frustrating as my attention was continuously split between the ‘live’ group in front of me and the online group on my computer and I worried that I was not doing justice to either of the groups. Another issue was the initial unfamiliarity with Zoom—both from a software as well as hardware end—and juggling that with the PowerPoint slides that I used for teaching was challenging. In retrospect, this was obviously a short-term solution that was more about keeping the classes going than ensuring that the learning taking place is centre stage. Another experiment that I tried was to split the class time into two so that each group had some live interaction. As the duration of the classes were fixed, I could only spend half the duration of the class with each group and this meant that the content was not being delivered as planned and had to be modified to fit the timeframe. However, this was not ideal as the group not having the live interaction either had to do some reading or watching related to the subject. As these were younger diploma students who were unused to self-directed learning, there was a vast variation in how they complied with the instructions. While some of the students tried hard to be engaged in the given activity, I could sense that they were disturbed and distracted by the ones who used this opportunity to mess around. Finally, as this was the first time I was trying to do something like this, there was no frame of reference for the students or myself. This too would change in a very short time with the start of the circuit breaker8 in April when we had to go completely online.

Phase 2 – March/April 2020

The few weeks of online classes before the close of teaching was a painful learning curve, perhaps more so for me as an educator than for the students. The rude shock of realising that what worked for me in face-to-face teaching was failing abysmally when on Zoom was disturbing. For example, one of my classes was with a group of students that are not very vocal in class and one of the strategies that I had utilised successfully to draw them into discussions was to approach a student and ask a question so that it seemed to be a one-on-one chat. When I tried this on Zoom, we had technical issues such as some of their microphones not working or the bandwidth dropping so that they could not turn their cameras on, etc. Further, the virtual distance made connecting with the students even harder.

In addition, there was also the ordeal of working from home—not just for me but perhaps, here, more for the students. We inhabit two spaces simultaneously while videoconferencing—the physical space as well as the virtual space and each of these come with their own challenges. The virtual space is impacted by variations in bandwidths, hardware, software and a steady connectivity while the physical space is a shared space with friends or family. I well remember the first time a young child—a sibling of one of my students—wandered into the space while we were having a heated discussion on theatre and sexuality. The startled look on my face when I stopped speaking mid-sentence made the whole class laugh. In later discussion with the students, many expressed their discomfort and disorientation in having to convert their family space into a ‘college’ space.

On reflection, this is not a unique problem. In an article in Postdigital Science and Education titled “Quarantined, Sequestered, Closed: Theorising Academic Bodies Under Covid-19 Lockdown” the author, Lesley Gourlay, reports on an interview study conducted at a large UK Higher Education institution during the COVID-19 ‘lockdown,’ analysing the accounts of six academics. She states that:

the sudden and enforced nature of the lockdown necessitated this sort of creative improvisation, in which spaces which were hitherto private, domestic, and intimate are changed in their nature, arguably becoming outposts of the campus and the world of work.9

The author goes on to suggest that the screen becomes a kind of “portal” through which a professional identity must be performed.10 This is an interesting notion that suggests that we need to rethink and re-evaluate our understanding of ‘campus’ as no longer being a fixed, material space. The idea of a ‘virtual’ university is not completely new, but, in this case, the necessity for a sudden change in mindset as both educators and students have to shift from the expected physical classes to virtual ones was a struggle for everyone.

Another issue I faced was the difficulty that the students experienced in staying alert and listening during online sessions. This is an issue experienced by other educators, for example, according to D’Cruz and Dennis, in their article “Telematic Dramaturgy in the Time Of Covid-19,” their students too found the experience very fatiguing:

far from any feelings they associated with making a live performance, they were more like zo(o)mbies. Professor of sustainable learning Gianpiero Petriglieri (cited in Jiang 2020) attributes this state of not-aliveness to a perceptual dissonance that causes conflicting feelings and states that this is exhausting for participants.11

This “not-aliveness” was something that troubled me deeply when faced with online teaching. Both as a theatre practitioner and educator, I realised that I cherished and privileged the ‘liveness’ that is central to both theatre and teaching. I realised how important this was in the classroom when I was faced with virtual teaching—not being in the same physical space left me feeling as though I had lost some of my senses and that this made ‘reading’ the reactions of the students extremely difficult.

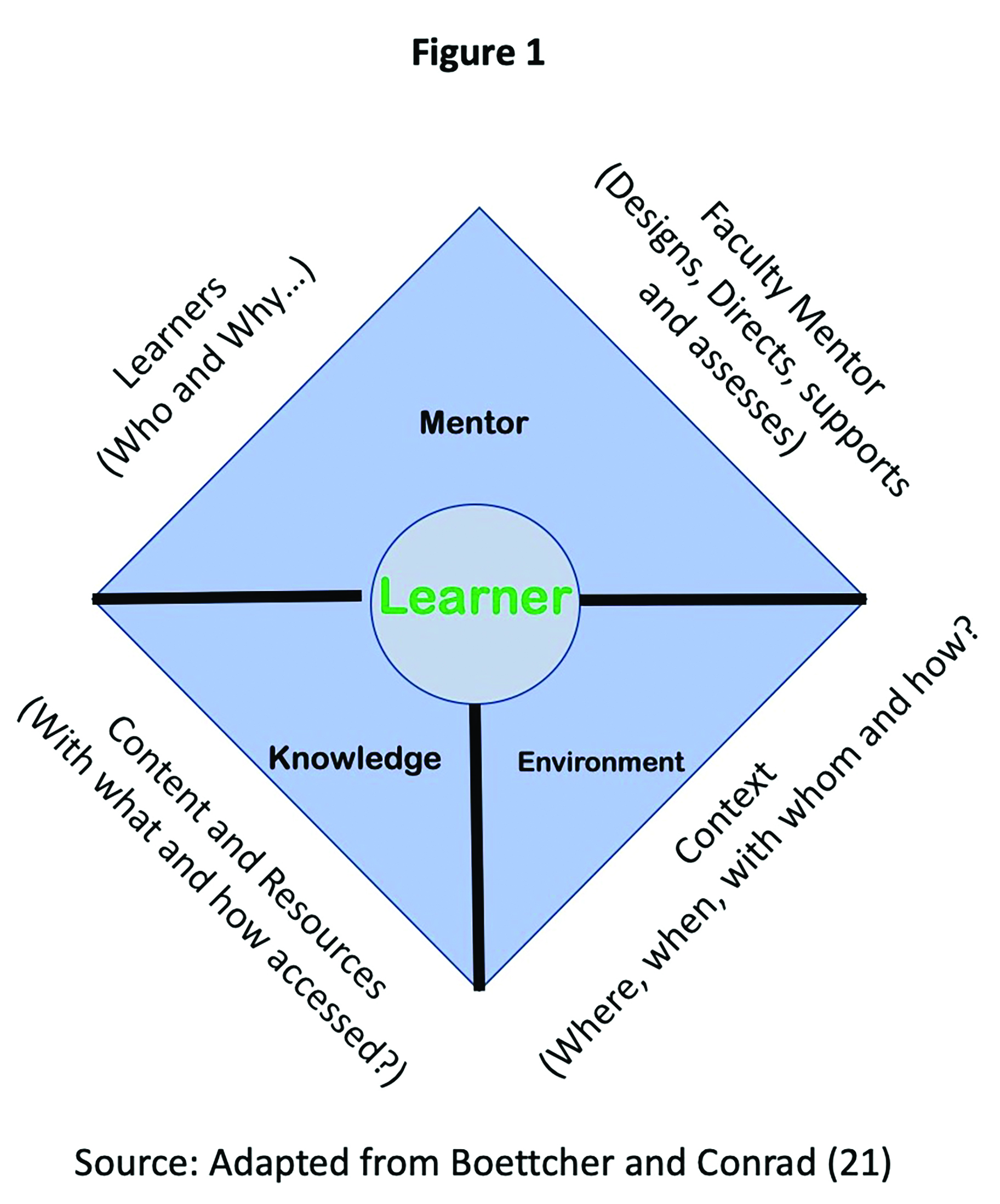

Obviously, the way in which the content was delivered by me during those weeks of lockdown was far from ideal. Boettcher and Conrad list ten core learning principles that guide the design and delivery of online courses where the first principle to follow when creating an online course is that “every structured learning experience has four elements with the learner at the center.”12 These elements are:

- The learner as the center of the teaching and learning process

- The faculty mentor who directs, supports, and assesses the learner

- The content knowledge, skills, and perspectives that the learner is to develop and acquire

- The environment or context within which the learner is experiencing the learning event13

This is illustrated in the following figure which again emphasises the importance of learner-centric approaches.

Fig. 1 The Learning Framework (adapted from Boettcher and Conrad).

Firstly, as I have mentioned before, the courses were planned for face-to-face delivery and in taking them online in such a sudden fashion, there were inevitable difficulties. The most challenging of those being “the environment or context within which the learner is experiencing the learning event.”14 I would contend that for most students studying online courses, there is already an acceptance of the very nature of remote study while, for our students, this new learning environment was forced upon them. However, within a week or so I found that most of the students had adapted to the virtual nature of the classes—perhaps because of their familiarity with social media while I, as a teacher, still struggled with the virtual world. Quite apart from having to adjust to this new mode of content delivery, what I missed the most, is being able to ‘read’ their reactions. The silence when I asked a question or asked for an opinion…waiting…hoping for a response is terrifying.

Therefore, when I reflect on those weeks, I am afraid that instead of the student being at the centre of the learning experience, being directed and supported by me, it was more a case of doing something and hoping for the best. Therefore, it is fair to say that during this phase, neither the planning nor the execution satisfied the first principle to follow while planning an online course that “every structured learning experience has four elements with the learner at the center.”15

Another principle that Boettcher and Conrad write about is “Principle 10: We Shape Our Tools, and Our Tools Shape Us” where they explain that, “that learning occurs only within a context and is influenced by the environment.”16 However, while in traditional classrooms this environment is created by personal interaction, the tools that shape the environment in a virtual space are our personal computers, tablets, mobile phones etc., “these tools create an environment that is transformed and infused with powerful psychological learning tools.”17 The communication patterns between teachers and students change and many teachers struggle with this as they move from being the centre of classroom communication to its periphery. Further, in this kind of online learning environment, the students have the power to customise their learning experience. Therefore, a thorough knowledge of the tools that create this new learning environment is vital. Indeed, at the end of that semester, as faculty reflecting on the weeks of online instruction, there was the realisation that where we failed the most was in not having a clear plan for the realities and difficulties of online teaching.

Phase 3 – Semester 1 September to December 2020

The planning for the first semester of the academic year starting in September 2020 needed to be agile as we had to account for face-to-face, blended and online learning. In the chapter “An Introduction tTo Rethinking Pedagogy for a Digital Age” authors Beetham and Sharpe explain the importance of ‘design’ in planning a class and explain that:

Classroom teaching with minimal equipment allows us to tailor our approach to the immediate needs of learners. Tutors can quickly ascertain how learners are performing, rearrange groups and reassign activities, phrase explanations differently to help learners understand them better, guide discussion and ask questions that challenge learners appropriately. With the use of digital technologies, all of these pedagogical activities require forethought and an explicit representation of what learners and teachers will do.18

Thus, the process of course redesign requires extensive reflection and planning in order to transform the learning process. The Programme Leaders and Contextual Studies Lecturers for the BA in Acting and Musical Theatre courses discussed best-case scenarios and worst-case scenarios and planned for them. We discussed innovative ways in which we would adapt to using online tools to help student learning. I came across the term “disruptive innovation” in an article titled “The Transformation of Higher Education After the COVID-19 Disruption: Emerging Challenges in an Online Learning Scenario” while researching for this paper which, in retrospect, explains what we attempted to do. According to the authors García-Morales et al.

Disruptive educational innovation replaces existing methodologies and modes of knowledge transmission by opening new alternatives for learning. It also introduces new advances in education systems through information and communication technologies.19

We had to rethink and redesign the way the curriculum would be delivered as well as learn to incorporate technology in new and innovative ways. It is this kind of innovation that would hopefully lead to “the transformation of the role of students and the way they absorb and use educational knowledge.”20

While it is difficult to quantify, I do believe that we did achieve some of that innovation and transformation in the last academic year. We did manage to ensure that there was greater student-centred learning through the incorporation of more digital material. For example, we were lucky enough to have an expert in Sanskrit drama in India, the eminent Professor Rustom Bharucha, kindly record a masterclass on the Natyashastra and the play Shakuntala which included pre-readings on the subject, recordings of performances as well as a talk that provided excellent context. This was extremely valuable in giving the students access to specialised knowledge on a completely digital platform curated especially for them. The reason this example of self-directed digital learning worked is perhaps because it was designed with forethought and a clear understanding of learning outcomes specific to this situation. A further advantage was that as all the material was online, the students could access and digest the material at their own pace—this is an example of asynchronous learning which is controlled by the student, which is very important in online and blended learning environments.

Another innovation that was very popular with the students was the inclusion of debates in class. I have had debates in class before but they were more impromptu and the idea was to generate a healthy, critical discussion. Therefore, here, it was not the debate per se that was innovative but the way in which we managed to conduct it in a hybrid learning environment. Despite the fact that some students presented the debate via Zoom and some students were in class with me, it was heartening to see that the level of involvement of the students was the same across the board. Maybe the mitigating factor here was that each group of students got a turn to be in class during the three debates that were conducted.

The pastoral care that we included in the planning was to conduct frequent feedback sessions and to ensure that both the in-class groups as well as online groups had sufficient one-on-one time with the lecturer. This again proved very effective as the students felt that their concerns were being addressed and at the same time, as the teacher, I was given the confidence that we were moving in the right direction.

Phase 4 – Semester 2 January to April 2021

Even with the change in Semester two of most classes going face-to-face, some of these practices continued—for example, greater student engagement in the classroom via research and discussion. In every class, some of the students would present their research on a chosen topic related to the subject of the class leading to discussions which ranged from thought-provoking to hilarious. On a side note, I was absolutely thrilled and gratified when I heard Peter Sellars, (one of the keynote speakers at the Arrhythmia: Performance Pedagogy and Practice, an online international conference held June 3-5 2021) talking about making students the teachers and the importance and impact on their learning when they have to teach others.

It would be fallacious on my part if I didn’t acknowledge that there were things that I tried which did not have the effect that I intended. I came to realise that some of the courses that I taught were rather content-heavy and that this did not carry over very well into the hybrid or blended learning scenario. For instance, I found that I had too many examples of tradition and culture that the students had to learn about in order to contextualise the theatrical forms we were studying as part of Asian Theatre. I had to re-evaluate and jettison some of the material and rather than prioritising content I prioritised learning the core concept—that the traditional theatre forms that they study are heavily informed by the culture. It is no wonder that Boettcher and Conrad state as their fourth learning principle “all learners do not need to learn all course content; all learners do need to learn the core concepts.”21

My experience with Boettcher and Conrad’s fourth type of course—the fully online course—came about in the second semester when I was asked to teach the Common Module course for level 1 Diploma students.22 This was a unique and valuable learning experience for me as I would be teaching pre-prepared lesson plans completely online on the Zoom platform. Each of these lesson plans was prepared by lecturers from a variety of disciplines but would be delivered by me to the class that I was assigned. Simultaneously, the same content would be taught by different lecturers to different classes with a cumulative total of more than 400 students.

Crystal Lim-Lange in a CNA commentary “COVID-19’s Education Revolution—Where Going Digital Is Just Half the Battle” talks about the Minerva Project, a futuristic university headquartered in San Francisco and their innovative approach which focuses on interacting and drawing responses rather than instructing.23 Founded in 2011 by Ben Nelson, Minerva offers undergraduate programmes where all learning is done online. At the heart of their education philosophy is the idea of “active learning” where the emphasis is on how students learn and not on what they learn.24 As Lim-Lange explains, “Lessons started with a ‘hook’ at the beginning of a new learning topic—a visually stimulating image, an emotionally striking story or a thought-provoking question that caught attention, then students were placed in breakout rooms to work on short live projects.”25 She could very well have been describing the lesson plans that I was given to teach. What made this course special was that each lesson was organised around learning about a central concept and the discussions, class activities and post-classroom extensions were all geared towards this. I had the opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of this approach during the one-on-one tutorial when the students gave very positive feedback on their experiences.

On reflection, what made this course work is perhaps that it was designed for online teaching and that it followed Boettcher and Conrad’s first principle that every structured learning experience has four elements with the learner at the centre.26 The learners had access to course content including the slides used in class, the videos as well as other reading material that they could access before and after the class. The teacher was more a mentor who guided the student’s through the learning process rather than delivering content through a lecture. This, again, resonates with Boettcher and Conrad, who go on to explain that, “the fourth element, the environment, answers this question: ‘When will the learning experience take place, with whom, where, and with what resources?’”27 The learning took place over Zoom during a fixed time and the resources used were online resources as well as breakout rooms for discussion. Therefore, in this case, the course design comes close to what the authors describe as being the most effective one for online courses.

Transformation: Changes That Are Here to stay

The above reflections demonstrate that we have struggled but coped and, at times, triumphed in planning and delivering courses in a variety of ways. One change that is maybe here to stay is the need to strategically use technology in our course design. In their chapter “Designing courses for e-learning” authors Sharpe and Oliver maintain that in courses that need to incorporate more technology into their design to cater to blended learning environments it is the redesign process that is crucial for transforming the learning experience. This redesign process examines the current course design for things that work and will not work in a blended environment as well as the student feedback. They recommend that the redesign process must be done as a team and that the staff have the time to properly integrate face-to-face and online material.28 They caution that technology shouldn’t be treated as a ‘bolt on’ and used blindly alongside existing course design. Instead, they recommend that the most useful approach is to try and incorporate technology into a course with a constant questioning of its purposes and how it serves the teaching process:

This ongoing, transformative engagement with teaching serves a double purpose: it guides the use of technology, but at least as important, it provides academics with the incentive to reflect upon their teaching and learn from the problems that technology adoption can create.29

This is a recommendation that we should most certainly follow as part of the periodic reflection of our own practice, be it in the classroom or on the stage, is an important mindset to have as theatre educators during disruptive times or otherwise. What started as a redesign process to cope with the sudden disruptions has instilled in me a new desire to come up with innovative ways in which course content can be taught, be it online or in a classroom. As part of this reflective process, I have come to realise that my understanding of pedagogy has had its own transformative journey from teacher-centric methodology to a more learner-centric methodology which encourages active learning.

Another realisation that I came to during this research process is that I am not alone—apart from my College colleagues, of course. I was heartened by the sheer plethora of blogs, newspaper articles, journal articles and even books that address the issues that are challenging the field of education and, in particular, theatre education. Perhaps the flip side of the globalisation that allowed for the rapid spread of the coronavirus is the global networks that have been formed to address the problems caused by the same virus. An excellent example of this is ATHE’s Theatre Online Pedagogy and Online Resources that provides ideas, links and how-to knowledge for theatre educators.30

From a pedagogic perspective, there is a gathering momentum of writing that examines the transformation happening in education and the performing arts—from writing in academic journals to books, researchers are gathering data and postulating models that will probably transform the ways in which we understand education. For instance, authors Li et al. in their journal article “A Hybrid Learning Pedagogy for Surmounting the Challenges of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Performing Arts Education,” published in June 2021 conducted a survey of teachers and students at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts to assess how effective the ‘hybrid learning’ implemented during the second semester 2020/2021 was.31 Not surprisingly, their conclusion is that the success of a hybrid pedagogy depends on the effective melding of technology, learning environment and a blend of synchronous and asynchronous learning—in other words a successful course redesign such as those recommended by Sharpe and Oliver.32 Routledge alone has numerous publications such as Online Teaching and Learning in Higher Education During COVID-19 – International Perspectives and Experiences edited by Roy Y. Chan, Krishna Bista and Ryan M. Allen which came out in August 2021 and others such as Performance in a Pandemic edited by Laura Bissell and Lucy Weir, and Pandemic Performance – Resilience, Liveness, and Protest in Quarantine Times edited by Kendra Capece and Patrick Scorese which are due to be published in 2022. An inevitable inference at this point is that irrespective of the end of the pandemic we cannot go back to where we were before. The challenges that we have faced have irrevocably forced a transformation, not just in the ways that we teach but in our very understanding of pedagogy.

On a personal level, the issue that had troubled me the most at the beginning of this reflective process was my own resistance to teaching online—as, perhaps, at the core of this resistance is the idea of ‘liveness.’ In my decades of experience in theatre, the embodied experience of acting and experiencing theatre is something that I have cherished. Further, teaching in a conservatoire where experiential learning is encouraged and fostered, the ‘liveness’ of theatre seems to take centre stage. Therefore, both as a theatre maker and as an educator ‘liveness’ is something that I perceive as being essential to my practice. However, looking back not just at my own teaching experience but at the ways in which theatre makers have not just coped with but overcome restrictions this resistance seems short sighted. Writer Toczauer offers glimpses into the experience of various educators and their innovative methods and, while there are some successes, many of them feel certain kinds of subjects need face-to-face interactions.33 On the other hand, examining the “strengths and limitations of Zoom for generating affective qualities (such as intimacy, immediacy, kinaesthetic energy) associated with live theatrical performance” D’Cruz and Dennis conclude that despite their initial resistance and the scores of:

practical, technological, emotional and pedagogical problems generated by being forced to teach and make creative work online, most students enjoyed the experience of developing their media skills and learning how to work in the online space as live performers.34

Nevertheless, not surprisingly, in both these articles and many others that I have read there is a decided preference for going back to ‘live’ theatre.

However, this does not preclude the fact that perhaps it is time to re-evaluate my understanding of what ‘liveness’ means in education. Perhaps the screen is not as much of a barrier as I perceive it to be. Looking back at my experiences with supervising students for the dissertation this year which were completely online, I did not feel any sense of discomfort or resistance. If anything, the online nature made the sessions more intimate and focused and free from the constraints of finding a common physical space to meet. Therefore, I would say the most obvious transformation is in my own attitude to teaching and learning. While it would be presumptuous on my part at this stage to suggest that disruption is something that educators need in order to innovate, perhaps a bit of disruption is sometimes necessary in order for us to periodically rethink, reassess and reinvent our approaches to teaching.