Keeping the Distance – Introduction

Lockdown, circuit breaker, and social distancing are some of the words and notions of disruption that became a lived reality for people around the globe in 2020 and much of 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic has caused us to change regular rhythms and altered movement patterns in everyday life. The symmetry of work, relationships, and routine activities were severely unsettled with few answers to questions of when it will end, or when the new normal might begin. Our bodies were made to spatially distance, which may be more accurately described as physical distancing defined by mathematical measures taking the form of metres or the number of people we were allowed to meet, rather than social distancing which could be overcome through the use of technology. These circumstances subsequently had severe impacts on tertiary dance education in Singapore and globally.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that traditional notions of teaching and learning in tertiary dance education at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) were halted for several months. Dance lessons that would normally take place in a studio setting were either replaced by homework or moved online. As a consequence of these shifts in delivering the learning objectives, educators were unexpectedly forced to learn and improvise with digital media and enact a fundamental shift in the way they communicated and interacted with students. In other words, all of a sudden, tertiary dance education took place via laptops and desktop computer screens which subsequently heavily influenced the accessibility and fluidity of dance learning, creation, and performance.

At NAFA, this was followed by the implementation of blended methods of teaching and learning towards the end of 2020, where on some days lessons were taught online, and on other days a limited number of students could take part in face-to-face teaching within a restricted dance studio setting at the academy. While using digital media in dance learning, exploration, dance creation and performance practices is not at all new in the 21st century, it was imposed upon dance educators as the only way – albeit temporarily – forward within the given circumstances of COVID-19.

Communication in dance learning, creation, performance and movement exploration naturally includes physical expression and the use of our human senses while training, exploring or performing together.1 It also includes facial expressions, haptic communication and the use of space to communicate and interact with each other.2 This is especially the case in dance improvisation lessons. Wearing face masks and not being able to have any physical contact, due to COVID-19 restrictions imposed at that time by Singapore’s Ministry of Health, limited students’ abilities to connect and understand facial or even verbal queues in communicating with each other. From a pedagogical perspective, this has created challenges and opportunities simultaneously. How, for example, can we achieve and deliver dance improvisation curriculum objectives while dealing with the inability to read each other’s facial expressions, the incapacity of students to experience any physical contact, and the lack of opportunity to learn and explore dance in a collective space?

In the following paragraphs I critically reflect, analyse, and discuss how my approach to teaching and learning has shifted and changed throughout the process of planning and delivering dance improvisation lessons online in late 2020. I begin with a short definition of what I am referring to as dance improvisation and the use of self-study research as a method for inquiry.3 This is followed by a reflection and analysis of challenges I faced during the initial planning and implementation phase for the online lessons, and how these challenges created new opportunities for interdisciplinary learning. I conclude the paper by discussing the learning outcomes and new skill sets students have been able to acquire, as well as the pedagogical benefits I have been able to gain by expanding my own teaching dexterities and practices.

Improvisation and New Learning Environments

Dance improvisation combines the creation and execution of bodily movement instantaneously. The movement creation by dancers or dance students thereby originates without any pre-planning.4 Blom and Chaplin explain dance improvisation as a “creative movement of the moment” and method “of tapping the stream of the subconscious without intellectual censorship, allowing spontaneous and simultaneous exploring, creating and performing” of dance to take place.5

Exploring bodily movement possibilities through improvisation can also break “culturally determined taboos about body boundaries and personal space.6 For example, in dance improvisation individuals can physically experience how to communicate through sensing others, as well as exploring how their bodies react to touch and being touched as a way of non-verbal communication. In turn, this process can lead to an increase in bodily and psychological comfort in individuals.7 During the process of teaching dance improvisation online, students were not able to experience these notions of bodily interaction within a shared space.

Student’s learning environments play an important part in the action of, reaction to, and interaction between individuals in dance improvisation as well.8 In other words, in dance improvisation lessons students can realise the “embeddedness of thought in experience as it emerges” during and through their physical interactions and in relation to the environment that surrounds them.9 Whether they are in a dance studio or exploring their moving bodies as a response to a particular site within an urban environment, for example, can play a part in stimulating their interactions.

While improvisation students would naturally interact through their moving bodies, the COVID-19 pandemic, and its ensuing need to shift teaching and learning to online platforms, made these physical and simultaneous spatial explorations impossible. Needless to say, this has created various challenges for student learners, such as accessibility, spatial, and motivational challenges while learning in their homes. It also created numerous challenges from an educator’s perspective. These include overcoming obstacles in achieving the learning objectives, as well as the need to adjust the way I communicate lesson content to students. In hindsight, these experiences led me to critically reflect on my approaches to teaching and learning in tertiary dance education in general.

Endorsing Self-Study Research

One of the initial questions that came to my mind after a circuit breaker lockdown was announced by the government of Singapore from April to June 2020 was: how could dance improvisation be taught via a laptop or desktop computer? I also asked myself how I would be able to deliver the curriculum objectives and learning outcomes of NAFA’s Dance Programme regarding dance improvisation. Discussions with local colleagues and other dance pedagogues from around the globe revealed that they were asking themselves similar questions.

Teaching dance improvisation is complex and requires trust and empathy in the interactions between student learners and lecturers.10 Hence, stepping into the mostly unfamiliar realm of online teaching required me to find opportunities to maintain a trusting and empathetic exchange with students, as well as overcoming some cognitive and emotional barriers in planning and delivering dance improvisation coursework online. These barriers mostly existed due to the firm belief that dance and dance improvisation can only be taught in-depth with students and lecturers being physically present within a given learning environment, such as a dance studio. However, as this was no longer feasible during that early point of the pandemic I needed to overcome these thoughts in order to be able to expand on my teaching skills and practices.

I subsequently started to reflect on cognitive and emotional aspects alongside previous teaching experiences during the planning and ensuing online teaching processes. Existing literature on self-study research and various teaching practices were thereby beneficial.11 For example, I critically analysed how teaching online is or can be different to being physically present within a studio teaching context.12 Moreover, I explored how dance improvisation online lessons can be taught in various ways while also emphasising NAFA’s curriculum objectives. This included the importance of providing students an enriching teaching and learning experience. I noted these thoughts and ideas in a research journal in which I regularly reflected upon my teaching practices.

The regular reflection on my thoughts, ideas and teaching experiences subsequently led me to overcome the initial challenges I addressed above. In other words, self-study research helped me to transform my thinking about teaching dance improvisation online.13 It has also helped me to expand on my teaching practices in ways I could not foresee prior to the need to shift to online teaching and learning.

From a different perspective, the use of self-study research to critically reflect on my teaching practices has enabled me to uncover thoughts and emotions that can also be perceived as a form of qualitative data informing this research.14 I explain more on these thoughts and findings in what follows.

Overcoming Challenges

Shifting away from teaching dance improvisation within a studio context entails overcoming curriculum delivery challenges, accessibility and technical issues, spatial challenges, and at times motivational challenges where some students became uninterested in part due to the lack of social interaction during the home-based learning period. I explain these challenges in greater detail below.

Curriculum Delivery

The aims and objectives of the Dance Improvisation module at NAFA’s Dance Programme include the development of creative skills through structured and guided movement explorations. Over the duration of their studies, students get to experience various approaches to dance improvisation while an openness to sensitivity and responsible movement exploration is emphasised. Demonstrating safe dance practices, as well as being compassionate when working with others, is also reflected in the anticipated learning objectives of the academy.

Furthermore, the dance curriculum expects students to display an ability to apply and maintain corrections given by their lecturers, as well as developing a capacity to discover their personal voice during dance improvisation. Teaching and learning strategies to achieve these aims and objectives include practical improvisation exercises, studio observations, peer discussions, the use of audio-visual material, and formative feedback by lecturers.

While most of these curriculum objectives are arguably common practice in tertiary dance education, these were created based on the assumption that students and lecturers are physically present while the teaching and learning process takes place. As COVID-19 restrictions required learning to take place online, my colleagues and I faced the challenge of addressing and delivering these learning objectives while making online learning in dance improvisation interesting and accessible for all students.

Creating Accessible Learning

Some of the most challenging issues to consider while shifting to online teaching was to create accessible learning for all students. This included reflections on how improvisation exercises may be structured and subsequently be undertaken by students within the spatial constraints of their homes. For example, while some students live in, or have access to, large spaces where they can easily move around and dance safely, other students live in small spaces with little room to safely explore their moving bodies. I did not know about any individual student’s circumstances regarding their new or makeshift learning environments until after the first online dance improvisation lesson.

Fig. 1 NAFA dance alumni Aloysius Tang improvising at his Singapore home, 2021.

Photo: Aloysius Tang

This made it initially challenging to plan exercises that are in line with curriculum objectives as well as safe dance practices.

Another salient issue to consider was students’ access to digital media and electronic devices. While more affluent students own laptop computers, have high-speed internet access, and possess the most up to date mobile phones and software, other students had to deal with internet connectivity issues or a lack of access to sophisticated computer hardware. While I was not aware of every student’s socioeconomic background, during the very short planning stage before moving to online learning, I did know that every student has a smart phone with video recording capabilities. I thus decided to try and make use of this common denominator in order to create equal learning opportunities for all students throughout the course.

Moreover, I decided to incorporate the use of video recording as one of the main tools to help students explore dance and the moving body, record and share their movement experiences, and to subsequently reflect on their learning through discussions with their peers as this is in line with the curriculum objectives. In general, students very much enjoyed this somewhat unusual approach to dance improvisation lessons, though over the duration of the semester some motivational challenges started to emerge.

Motivating and Engaging Students

As mentioned above, some students had little room to move while learning from home. In most instances, these learners were also the ones with internet connectivity issues. Based on my observations and reflecting on feedback from students, I assumed that the combination of spatial challenges and connectivity issues led to a lack of motivation to learn in some students.

Another concern that led to motivational challenges was the lack of physical interaction between students during lesson time, but also outside of regular curriculum hours. As Singapore’s population was legally required to stay at home due to COVID-19 restrictions over a prolonged period of time, students were feeling somewhat unmotivated to learn on some days as there was no end to the pandemic in sight and feelings of being physically isolated started to play their part.

The sum of these challenges subsequently led me to think, reflect, and re-imagine how I could facilitate online learning while also delivering the curriculum objectives in Dance Improvisation. Moreover, I asked myself how I could make online learning interesting, accessible, inclusive, and yet challenging enough to make students curious to learn more about what dance is or what dance could be.

Finding and Creating Opportunities

The need to overcome curriculum, accessibility, and motivational issues naturally opened the door to exploring new possibilities in teaching dance improvisation. The initial thought, and probably fear, I had was how dance improvisation could practically be taught online while also taking these issues into account. Rather than just teaching about dance improvisation and the underlying theoretic principles, some of which are discussed above, I wanted to find a way to let students physically explore their actions and reactions to given tasks and subsequently analyse and discuss these with their peers within a group setting.

In general, I did not change any content that I would normally include in dance improvisation lessons throughout a semester. The improvisation lesson content includes, for example, the physical experience and exploration of Rudolf von Laban’s movement qualities to develop students’ body awareness, the exploration of space and differing places with and through the moving body, playing with varying movement motifs, examining different cultural dance forms and their approaches to movement exploration, creation and performance, as well as looking at differing music genres in order to discover how our bodies can become the visual aspect of music by physically portraying what we hear, or to distort music in order to provoke actions or reactions in an audience. These topics can be taught online and practised while learning from home. What differs in comparison to studio teaching and learning, however, was the way students communicate with each other, as well as how students and I interacted throughout the process.

Transforming Communication

Under normal circumstances, dance improvisation lessons take place in one of the dance studios at NAFA. Occasionally students and I would also visit other spaces and places on campus in order to develop and explore site-specific dance improvisation. Whether students improvise at a site-specific location or in a dance studio context, the communication that takes place during these lessons includes verbal communication, the use of bodily senses, and physical touch between students. As shifting dance improvisation lessons online did not enable students to use their bodily senses or touch as ways of interaction, I needed to find differing notions to not replace but to facilitate methods or create spaces where some lively virtual interactions among students could take place.

I therefore split students into several groups who worked together in separate breakout rooms on Zoom. Each of these groups then discussed given tasks and decided how each individual student would undertake an improvisation exercise in their home. Each student was tasked to video record themselves with their mobile phone, and to subsequently share their improvisation exercise with their group members to reflect and discuss their thoughts and experiences. At the end of every lesson, one student from each group shared their video recorded improvisation exercise with all other groups. After students shared their videos, I started to facilitate discussions on the learning content and their thoughts and understanding about their moving bodies, but also on the way they documented themselves via video recordings throughout the process.

The short video recordings by each individual student subsequently served as a source of reflection on their own learning. It also served as a way to share what everyone achieved during an online lesson in their respective homes. By using this approach to teaching and learning within this context I aimed to address various educational objectives, such as accommodating different learners’ needs and stimulating the creative potential of students through interdisciplinary learning.15 Using this approach to teaching and learning also enabled me to address NAFA’s curriculum objectives.

Over the duration of the semester, students accumulated a number of video excerpts that eventually became a video diary of their dance improvisation learning journey. As part of recording their learning progress, I also asked students to take it a step further and think about how they could use the camera in different ways while filming. This was aimed to foster what students explore, or what they are trying to communicate through bodily movement and spatial exploration. At the end of the semester each student was then tasked to present a three to five minute short film that incorporated some of the module content with their recorded learning journey. While I did not grade the short film as part of the Dance Improvisation module, using this approach to teaching and learning enabled me to address all curriculum objectives on one hand, while on the other hand opening up new dimensions for interdisciplinary learning.

Interdisciplinary Learning

The use of video recording and sharing helped to bridge the spatial divide between the students and I. In turn, it also opened up opportunities to learn about the moving body from entirely different perspectives. Rather than concentrating on exploring a given motif through bodily movement within the context of a dance studio, students were practising in their homes which are very different spaces and places. For example, each student’s home consists of different dimensions, textures, light, and sounds, which added various scopes to the form of a dancer’s bodily movements. It also added numerous possibilities on how to capture and record movement and dance by means of film.

By using video recording as a method to capture, share, and reflect upon dance improvisation lessons during the pandemic, I was able to make the learning journey equally accessible for all students, regardless of their socio-economic background. This was vitally important to me as I, in line with Eeva Anttila, Mariana Siljamäki, and Nicholas Rowe, as well as Charis-Olga Papadopoulou, amongst others, perceive the role of educators to be at the forefront of promoting inclusive teaching and learning.16

While integrating technologies in education might be challenging in some respects, such as with regard to the nature of dance as a subject of study, it does create opportunities by making education accessible and potentially engaging.17 Moreover, using video as a means to capture, share, and reflect upon the student learning journeys also enabled me to adhere to the core principles and values of inclusive education. The student feedback about this approach to teaching and learning was very positive throughout the semester.

Over time, practising dance improvisation at home and video recording the exercises started to become both somewhat familiar and yet remained a very unique experience for students. As each individual’s home added its own dimension to dance and the moving body, I encouraged students to also explore how and to what extent they could use different camera angles and camera movements while recording their dance improvisation exercises. The ensuing editing work with the film material subsequently opened up new learning opportunities beyond the art of dance itself.

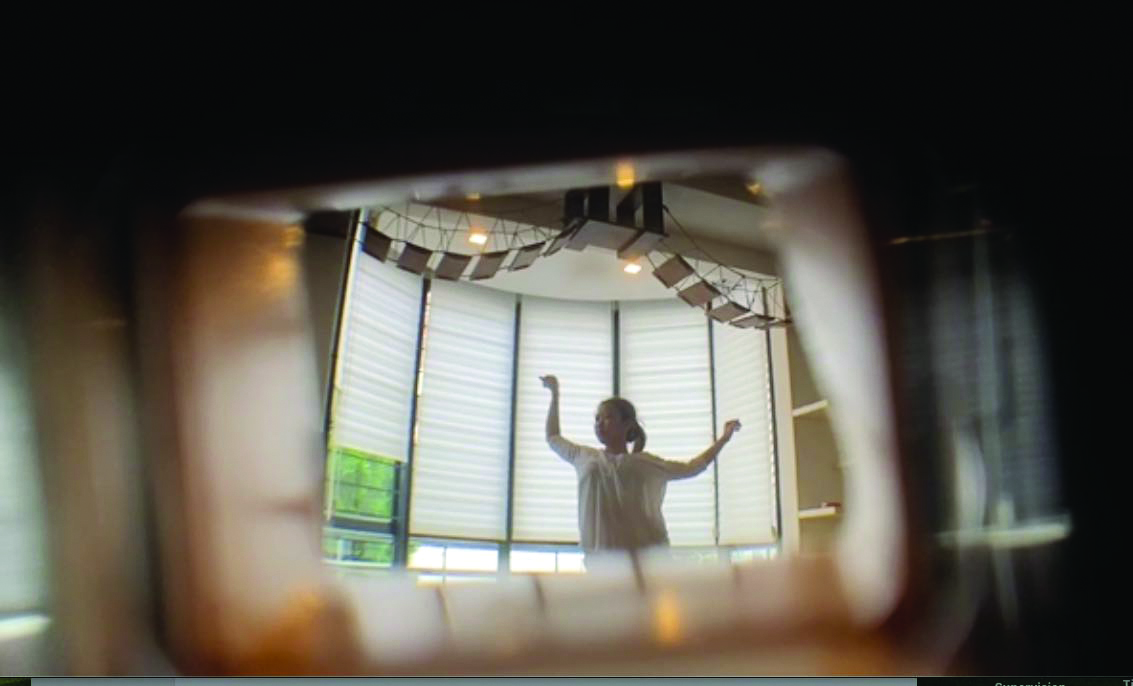

Perspective Taking

It was very interesting to note that while the students I was working with are very versatile in dance improvisation and creative in dance making for performances on a theatre stage, they perceived it as challenging to see dance from different perspectives to that of dance studio or theatrical settings. I thus asked myself, how I could get students to explore different perspectives on bodily movement, dissimilar spatial dimensions, and varying textures of light, for example. I also asked myself how I could teach students to take the spectator’s point of view; in other words, how could they learn to see through the eyes of a viewer?

To gradually untangle students’ confusion about how they could film their moving bodies from different angles and perspectives, I first suggested recording themselves from three different camera angles without any camera movement and by improvising with the same given movement task. Students could also ask to get recorded by one of their family members if they wished to do so. The considerations students had to emphasise included how different camera angles can change or influence the way a viewer may understand improvised movement material, how the spatial positioning of the moving body within a room can affect its mode of expression, and what influence different textures of light may have to the meaning of movement. Very bright light near a window in combination with some enthusiastic and fast movement may suggest a very happy person enjoying the sunshine, for example, while a very slow moving body in a dark and shady corner may point to some suspicious or sad movement expressions.

Fig. 2 NAFA dance student Sophie Lim exploring camera work at her Singapore home, 2021.

Photo: Sophie Lim Yann Yu

This exercise was then repeated by students with their cameras being required to either zoom in or zoom out while filming a dance improvisation exercise from each of the three respective angles. The final two steps were to allow the camera to travel while filming the moving body, and to zoom in or zoom out as the camera was travelling along various spatial pathways while recording the dancer moving in her or his respective place and space. The film material that students collected over the duration of the semester subsequently required editing to create their final product, a short dance film.

The exploration of dance through the lens of a camera added an additional perspective to the teaching and learning in dance improvisation. This interdisciplinary approach also added very personal dimensions to students’ works, which in turn required me to provide students with personal feedback. In line with existing research on the benefits of providing students with positive feedback about their ideas and achievements, students appeared to be more motivated, confident, and determined to master given tasks after receiving positive personal feedback about their learning.18 The feedback I provided for each individual student encompassed a mix of written and verbal formative feedback throughout the semester.

Learning Technology

As mentioned above, the video material that students collected over the duration of the semester was thought to serve as a starting point to create a short dance film. While I did not grade the dance film as part of the improvisation module, I did perceive the creation of the individual dance films as an important learning goal and in a sense tangible learning outcome at the end of the semester.

Most of the dance students, as well as myself, had only very modest knowledge and experience in film editing prior to the discussed semester. I therefore encouraged students to share their ideas and experiences with various video editing software during online discussions at the end of some of the improvisation lessons. In hindsight, I was more than positively surprised by how eagerly and passionately the vast majority of students engaged in these dialogues, as well as in the post-production work for their dance films.

The topics that were deliberated during these discussions included matters concerning the improvement of camera work, which editing software was preferable, as well as how to add music and adjust soundscapes in relation to the visual material. The learning about these technology issues was an additional bonus to the teaching and learning practices in dance improvisation.

Overcoming the challenges of not knowing where to start with teaching and learning dance improvisation online led to what Deirdre Ní Chróinín, Tim Fletcher, and Mary O’Sullivan describe as “pedagogical innovation.”19 In other words, the restriction and need to shift to online education has actually helped the emergence of new pathways in teaching and learning dance improvisation by fusing the learning process with another discipline, video/film making. Moreover, while I did not know how to teach dance improvisation online at first, I did find one possible pathway through critically reflecting on established teaching and learning methods and the subsequent search for strategies to create an engaging and challenging learning process despite COVID-19 restrictions being put in place. I thereby needed to embrace the use of technology and change my somewhat routine teaching and learning practices.

Embracing Change – Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic created opportunities to expand on well-established teaching and learning practices in tertiary dance education at NAFA and beyond. It also paved the way to critically reflect on and challenge my own pedagogy through the use of self-study research as a method of inquiry. This analysis subsequently helped to expand my capabilities and pedagogic practices in teaching dance and dance improvisation.

While the existing dance curriculum at NAFA sets the guidelines and establishes what learning outcomes students should be able to achieve within this module, I found one possible pathway to realise these aims and objectives while delivering the module online instead of in a dance studio. More explicitly, I created an interdisciplinary learning process by using video recording as a notion to capture, share, and reflect upon dance improvisation lessons during the isolation brought about by the pandemic. Observing students’ engagement during the learning process and reflecting on the learning outcomes and approach to teaching I took during the semester, it can be argued that while not without its challenges, teaching dance improvisation online can be beneficial for students’ learning journeys in tertiary dance education.

One benefit of teaching and learning dance improvisation online is the opportunity to develop new skill sets. For example, home-based learning helped students to think in different spatial dimensions by exploring the moving body from very different perspectives to that of well-established teaching and learning practices within a dance studio setting. While dance studios provide a blank canvas that students can draw on with their moving bodies to create shapes, pathways, and moving images, dancing at home requires students to negotiate the space with other objects and living species, such as chairs, sofas, or sometimes even their pets. They therefore had to analyse and solve such spatial challenges in order to fulfil the learning tasks. The challenge for me as the facilitator of the learning process was to guide students virtually instead of being physically present during the lessons. This shift in the approach to education was, retrospectively, an enriching experience.

Another skill set students acquired was interdisciplinary learning. In addition to using video recording as a means to capture, share, and reflect upon dance improvisation lessons by each individual, students learned how to plan, create, and subsequently edit moving images that portray dance as a way of expressing diverse connotations. Moreover, while commencing with the collection of short exercises that were filmed from different angles and perspectives by students themselves or one of their household members, the film material finally amounted to what can be seen as a dance improvisation diary of their home-based learning journey. Students later edited their film material to create a short dance film on their own as an additional learning outcome of the Dance Improvisation module.

At the core of dance and dance improvisation is the communication and expression of meaning through the moving body. Movement can thereby be created as a response to a feeling or sensual understanding. Listening and reacting to one’s senses is also a crucial part in the communication between dancing individuals, and arguably between individuals in general. Shifting dance improvisation lessons online meant that the physical distance that the use of technology created required students to find different modes of communication to that of physically sensing each other. Discussions students and I had after various online improvisation lessons revealed that not being able to physically sense others actually helped students to develop a better awareness of this vital notion of communication. In other words, the distance to others helped students to become more aware of themselves and reconnect with their senses. This learning outcome was a somewhat unexpected benefit of learning online.

Throughout the process of teaching and learning online it was important to provide students with guidance and ongoing positive formative feedback about their development in dance improvisation and their overall studies. The lack of social interaction with peers that normally occurs on campus during an academic year appeared to be one reason why some students seemed to occasionally become demotivated or uninterested to learn and achieve. I therefore perceived it as vital to reserve some time at the end of every lesson to facilitate group discussions during which students could share their thoughts and experiences while learning from home. Besides talking about the learning content, these conversations were also important to stay connected during this challenging time.

Dance learning, dance teaching, or simply dancing is a process that does not only require a bit of physical space for people to move their bodies. Dance is arguably also a social process in which people move together for reasons of joy, excitement, or as a way of challenging each other. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted our daily routines and altered some of our regular life rhythms. This was particularly so for tertiary dance education where learning from home was no longer optional due to the pandemic. In fact, it was the only way forward for dance education during much of 2020 and 2021. The use of technology helped to overcome some of these disruptions.

Using technology to teach and learn is not new or uncommon. While the use of technology in tertiary dance education is arguably here to stay, some of the questions that need to be addressed by educators and future research include what impact online learning may have on the physical development and training of dance students in the long term, as well as how the awareness of people’s feelings and sensual connections may be impacted by the lack of physical presence in online learning. While change is inevitable, and the arts are arguably a driving force for change and advancement in society, it is important to be mindful about the long-term impacts shifting pedagogies might cause in tertiary dance education.