This essay builds its argument around the relationship between contemporary art and art history. There is a tension that underlies this relationship mainly because the modernity of art is increasingly unable to regulate the interests of the contemporary, which in turn could not seem to elude the modern as its foundational discourse.

That said, the modern art museum persists to encompass the contemporary in the belief that the modern is always emergent and self-renewing, capable of marking the progressive in the contemporary. This modernity has shaped the history of art history as a discipline forged in the 19th century and linked to the formation of the museum, the nation-state, and a particular phase of capitalism.1 The discipline of art history has experienced a crisis of its methodology and scope, and has tried to expand itself beyond its zone of expectations. This expansion, however, has failed to radically reorganise its methodology. It tries very hard and, sometimes, belabours in vain to represent other art worlds through the very procedures of explanation that have refused them. In other words, it is imperative for art history to recast itself or to cast itself elsewhere: in the afterlife of the modern that conceived it. In this endeavour of recasting, we ask: How does an emergent modality of critical inquiry conceptualise this elsewhere and in this afterlife?

In Southeast Asia, the writing of the history of art has not been strictly guided by the discipline of art history. In terms of scholarship, the history of art proceeds from the concept of comparative modernity, with modernity as the main mode of explaining art and its vehicle for comparison across diverse art worlds. It is also through this concept of modernity that a range of differences plays out: non-modernity, anti-modernity, post-modernity, tradition, contemporary, and so on. The other mode is the ethnographic that tells stories of artists and the ecologies in which they work. It serves as an alternative to a strict art history, in light of the absence of a deep archive of art. The third mode is the contemporary in which the history of art is, at a certain level, narrated and reflected upon through the production of art in the present; a present that reflexively implicates the conditions under which art has been historicised.

This excursus looks at four instances in Southeast Asian art that foregrounds the contemporary as a mode of access to art history. These instances offer up four themes about the relationship between art history and the contemporary as well as speak to the concerns of this problematic dynamic, namely: the supposedly paradoxical liaison between past and future. The rubric of art history and the contemporary at a significant level indices this constant “déjà vu”— a recurrent condition that actually exemplifies the comparative, in which the progressive is arrested by the antecedent; or the vision of a possibility is bedevilled by an anxiety of history. What might be productive to contemplate is how theory puts in place the terms “end” and “post” in the exceptional markers of the self-consciousness: the modern, the colonial, and the historical.

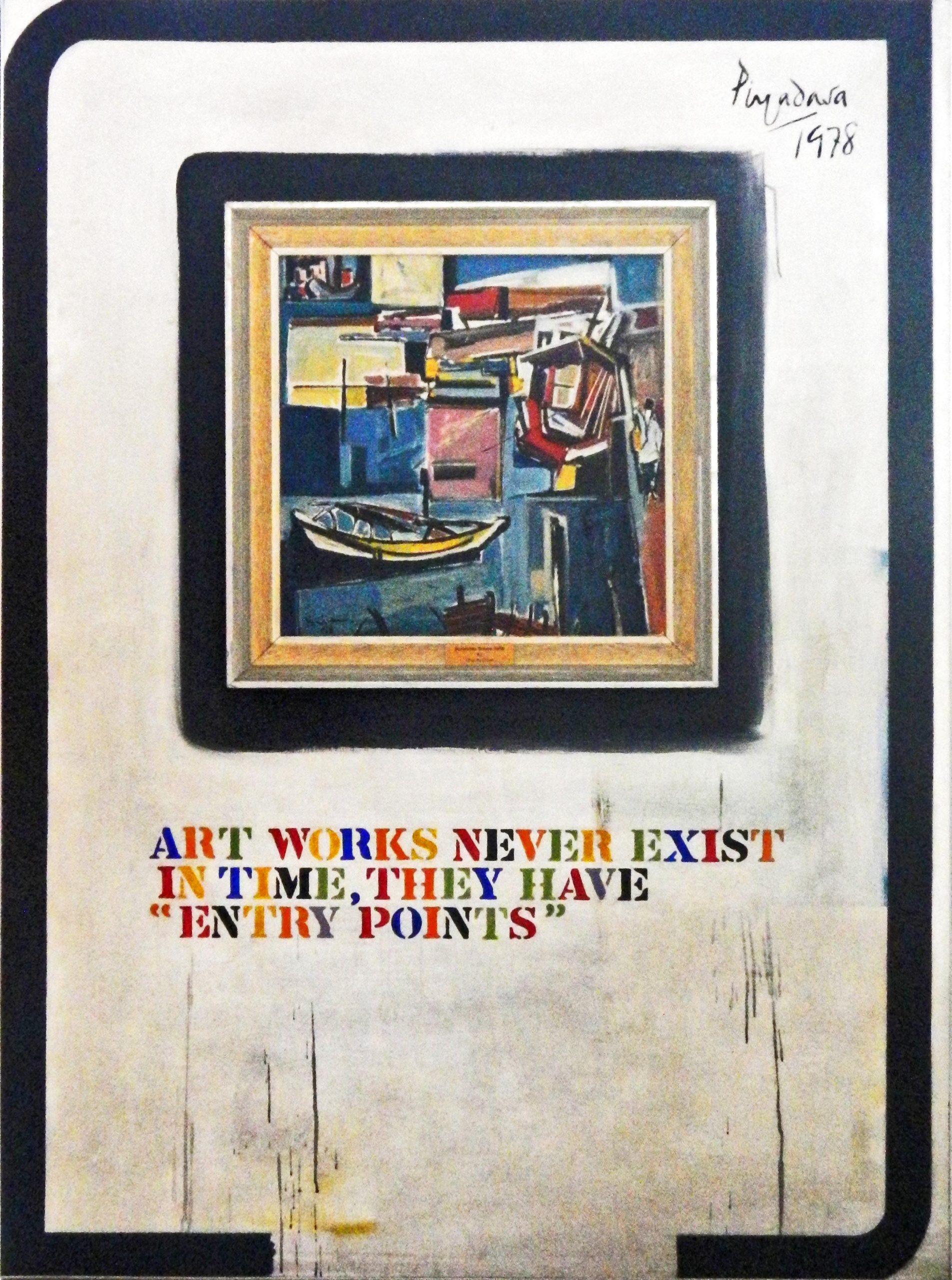

Redza Piyadasa,

Entry Points, 1978.

Mixed media.152 x 112 cm.

Collection of National Art Gallery Malaysia.

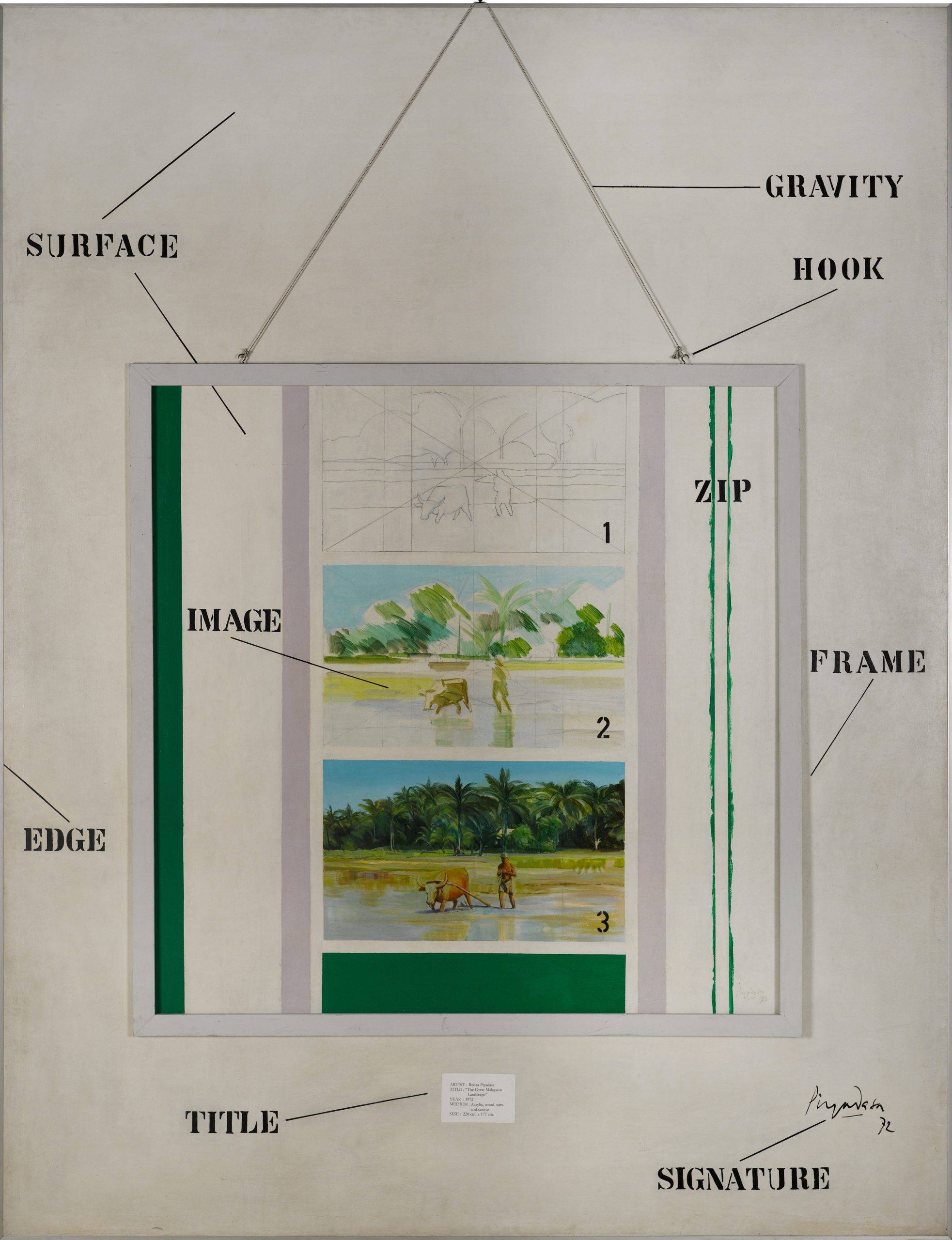

Redza Piyadasa,

The Great Malaysian Landscape, 1972.

Acrylic and mixed media. 152.5 x 106 cm.

Collection of National Art Gallery Malaysia.

Thesis 1: The contemporary locates trajectories.

“Art works never exist in time, they have ‘entry points.’” This quote is taken from Redza Piyadasa’s mixed-media work titled Entry Points (1978). It assimilates a 1958 painting by Chia Yu Chian titled River Scene into an otherwise bare canvas, stained only by trickles of paint, a broken border, and the stenciled sentence that disfigures the scene of the painting. Piyadasa’s comment tracks the modernity of art in terms of trajectories, not origins; transpositions, not lineage nor linearity. The idea that the work of art is approached through “entry points,” as opposed to having a fixed temporal existence, significantly skews the history of modernity. In particular, its self-fulfilling prophecy of progress may actually be a chronicle of a stasis foretold. Interestingly, the presence of the artist and the painting references the Nanyang School/Style.2 Chia Yu Chian was studying in Singapore at the time the work was painted, and this may have been Piyadasa’s way of calling out an entry point into a modernity in Southeast Asia that is being consolidated as a region—through a school of artistic and cultural thought—under the aegis of the Nanyang or the South Seas.

Phaptawan Suwannakudt,

Nariphon I, 1996.

Detail (image with the tree).

Acrylic and gold leaf on silk. 165 x 80 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

One such trajectory is the critique of art itself within the practice of artmaking, rendering the “critical” formative of the “artistic” at the fringes of autonomy. As a conceptual artist in the minimalist, kinetic, and constructivist vein, who questioned the basis of modern art and later the discourse of nation in Malaysia, Piyadasa first tried to reconceive the form of art, in his own words, as a “meta-language” within the purview of a Western avant garde. According to him: “My arrival at conceptual art engagements by the mid-1970s was prompted by the need to transcend the limitations of a painting/sculpture dichotomy as defined by Western art historicism. The attempts to break down separations between painting and sculpture were central preoccupations of the 1960s, very much a part of my generation’s concerns.”3 In this specific instance, contemporary art opens up a new way of imagining how art takes place, and is not merely mapped out across or grafted onto a grid called Art History. Here, the contemporary creates the conditions of the historical in relation to the passage of art.

Phaptawan Suwannakudt,

Nariphon III a, 1996.

Detail (image with three girls on the left).

Acrylic and gold leaf on silk. 90 x 90 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

According to Piyadasa’s account of the history of modern Malaysian art, in his earlier work The Great Malaysian Landscape (1972), “a conscious attempt has been made to focus on what has been termed the ‘eye/mind’ conflict in modern painting by the use of visual and verbal components.” This reflexivity lies in “a parody of the painting-within-a-painting situation…in which the stenciled words draw attention to…rhetoric governing…modern painting…. (and) questions about the nature of painting.”4 Here, the contemporary artist is also an art historian, and so conflating the tasks of production and historicisation that are performed, impressively, by the same person.

Thesis 2: The contemporary reinvests tradition.

There is the impression that the contemporary is the opposite of tradition, and that tradition needs to be transcended so that change can happen. Contemporary art has complicated this notion. The artist Phaptawan Suwannakudt from Thailand exemplifies the condition in which the contemporary cannot be rendered possible without the skill honed in the context of tradition. Tradition may mean the supposed knowledge generated before the time of the modern. What the contemporary tries to do is to cross the unnecessary gap between modernity and tradition. Phaptawan is the daughter of the esteemed Thai mural painter Paiboon Suwannakudt, and learned the techniques of mural painting under his guidance. When Paiboon died in 1982, Phaptawan, who spent her childhood in a Buddhist temple, assumed the role of her father and completed commissions for temples and hotels in Thailand for 15 years. Phaptawan’s practice has been a conversation between this history of skill and talent, on the one hand, and the demands of the present on subjectivity and agency, on the other. At this point, the question of gender and locality intersects with the conditions of migration. When Phaptawan moved to Australia in 1996, she described herself as a “Thai mural painter”5 but began painting on easels instead of the wall. Her work over the years, however, has revealed an array of expressions that enhance while simultaneously lightening the burden of this characterisation of the self. In many of her pieces, she is able to reflect on displacement and resettlement, and references modernism and customary forms of image making. For instance, her first paintings in Australia titled the Nariphon series (1996), feature gum tree figures in the scene. She relates that she “unconsciously painted a gum tree bearing its girl-shaped fruits to tell a story of an incident in a province of Thailand when a 12-year old girl was sold by her parents.” In a later work titled Journey of an Elephant (2007), she paints the trees she encountered in Sydney, names them in a language she knew intimately, and layers them with the text of a short story her father had written. This layering of worlds, texts and visions is also evident in Three Worlds (2009).

The art critic Flaudette Datuin points out that it was Phaptawan’s father “who taught her to discipline her hand through a mindfulness honed by meditation and guided by the Buddhist conviction that the ‘mind is the body and the physical is a vessel,’ from which we depart when we die. Form in Buddhist painting, she believes, is likewise a ‘vessel, in which the mind of the painter dwells. The mind dwells on the work during the process of painting, and when it departs, I leave the vessel behind. My work moves on from one vessel to another.’”6 Datuin further states: “when she was 14, for example, she asked her father why the line and form of water in his mural paintings did not look like the water she sees in a nearby river. Her father sent her back to look at the river again but this time with her eyes shut. ‘He then told me to empty the visual from eyes of flesh and see again.’ When she begged her father to teach her how to paint, he asked her to draw leaf after leaf, thousands of leaves, page after page. When she started painting murals herself, she did so with a watchful mind that observes the moment and movement of the brush/pencil entering and departing the surface. And every time she ‘arrives at the departure,’ she ‘catches the moment of the unattached mind. The watching of the mind will carry you through several enterings and departures [over] and over again.’”7

Thesis 3: The contemporary redistributes the modern.

An important element in the climate of contemporary art is the market. It is an issue that is, more often than not, repressed in the discussion of the aesthetic or isolated as a sociological matter, as if the production of art were not either a critique or affirmation of the capital that has produced it in the first place. The couple, Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan, confronts the market by way of art history. The artists converse with the art of Antonio Calma, someone who bears the stigma of being labelled a Mabini artist, a term assigned to painters who are deemed commercial. The term comes from the street on which they ply their trade, the same vicinity in which some conservative painters in 1955 relocated their works, after walking out of a competition in the annual salon that, according to them, favoured modernism. Mabini, therefore, serves as a sign of decline and persistence, an enduring salon des refusés that is contemporaneous with modernity. Calma is the Aquilizans’ contemporary in the art world; but he only makes sense in Mabini while the Aquilizans are supposedly global artists in biennales and art fairs.

Isabel and Alfredo Aquilizan,

FRAMED: Mabini Art Project at Art Fair Philippines, 2016.

Installation view. Courtesy of Alfredo Jojo Gloria and Art Fair Philippines.

In the hands of the Aquilizan couple, the works of Calma are subjected to different configurations: stacked into a column or a pile of canvasses, cut up and reframed, recast as minimal sculpture or readymade conceptual art that is totemic or muralist in aspiration, but still retaining the signature of a fragmented, miniaturised Calma. He has become some kind of a co-author, or cooperator, of contemporary art that has mutated into abstract, impressionist, informel, brut, nouveau realist, and so on. What happens to Calma is difficult to track, which is why this provocation is indispensable—it is at once so disturbing and so beautiful, with Mabini art finally becoming contemporary and museum-worthy, though slaughtered, so to speak. It is only through this slaughter that it achieves an aesthetic quality meaningful in the legitimate art world, but it is a slaughter that nevertheless denies it its own tradition on the street where it lives. This process of transformation of Mabini painting from commercial painting into an installation began in 2007. In a way, contemporary art reverts to a history of kitsch to achieve its valence of modernity.

In Art Fair Philippines in 2015, a reprise of this project was staged. A documentary was exhibited alongside a motley of pictures. In this theatre, Antonio Calma sat comfortably for the camera, posed against the fabled and majestic Mount Arayat, the mountain that presides over his place. Calma was actually ensconced. After all, this is his social world, his art world. He is a painter of landscapes, including the one that frames him. It is one that he sells quite copiously in his trade. He is what they would have called, back in the day, oftentimes with condescension if not outright derision, a Mabini artist; in our own time, he persists to stand his ground with his own gallery in Pampanga and Tarlac—a nest feathered by an atelier of artists and a cohort of loyal clients.

For the Aquilizans, the discourse around Mabini is a viable site from which to think about the circulation of art and the creation of its value: from the origins of the market during the reign of Fernando Amorsolo in the first half of the 20th century to present day scenarios in which primary and secondary markets briskly interact (sometimes vertiginously brisk). Mabini references a lot of logics vital to the commerce of art. It also implicates the afterlife of 19th century academic realism as a foundation of tourist and souvenir art in the American period when the Philippine exotic would be accessed partly through paintings of tropical charm and colonial curiosity. It relocates Amorsolo, the most well known Philippine painter in the first half of the 20th century, from a revered master of romantic realism, who is seemingly beyond the machinations of money, to a purveyor of taste and things in a wider economy of both kitsch and collectible. Finally, it complicates the notion of the contemporary itself. How do artists like the Aquilizans appropriate the lively practice and ecology of Calma in the context of contemporary art? Can Calma survive the translation or is it only the Aquilizans who gain from this contentious gesture? Both Calma and the Aquilizans have been recognised because of this project: exhibition presence for the latter and business prospects for the former. Can there be reciprocal mimicry here?

These questions are not masked in the art fair. Rather, they are laid bare, better for the public of the art fair to keenly revisit questions of value and the social life of commodities. In previous collaborations with Calma, the Aquilizans had radically intervened to make Calma’s oeuvre look like much more than it is in Mabini and its satellite retail outlets. In this fair, the Aquilizans decided to pursue another trajectory. They practically transplanted the gallery of Calma from its home grounds to the premises of the fair, and set it up as a gallery like any other display at the event. Iterations of the corpus of Calma, as at the Fair, has been significantly mediated by the Aquilizans and by this, the discipline of art history encroaches to historicise it. This cohabitation is meant to confuse, to productively confuse, so that the idea of the market and its political economy are viewed from a broader vantage, and that the modernism of art does not elude the critique usually reserved for commercial interests enslaved by lucre. An argument can be made that it is commerce all over, just like the salon hang of the works in both the galleries of Calma and the Aquilizans. And if it is so, is there nothing outside it? Does inserting Calma into the art fair circuit merely indulge the market, or does it finally disabuse it?

Thesis 4: The contemporary masters and mimics the Western gesture.

The work of the artist Mahendra Yasa, who works in Bali, exemplifies this final thesis. In contemplating contemporary form, he is seemingly bedevilled by a double vision: the vision of Balinese painting that has defined the idyllic conception of Bali and the vision of Western art, specifically American modern art, in an effort to overcome the dichotomy sustaining those binary visions. What he does is to transpose the techniques of Balinese painting to simulate the effect of so-called Western modernism. The effect is mimicry of the Western and mastery of the Balinese, an overinvestment in the production of surface almost on the level of obsession and devotion related to craft and ornament. It also references the viable commerce of painting in Bali that simulates Western style and exploits the local expression.

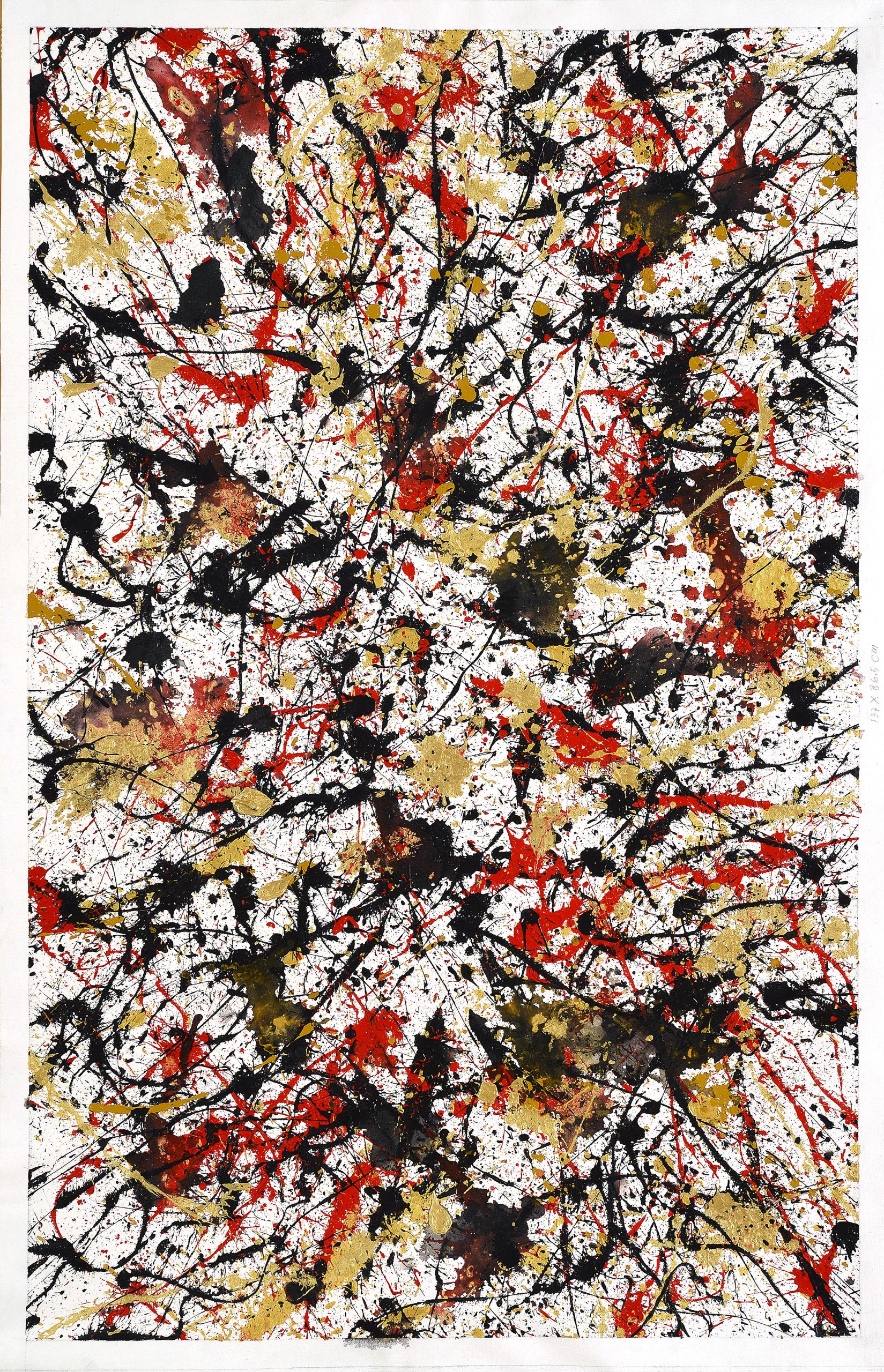

Gede Mahendra Yasa,

Rorschach #1A, 2013.

Acrylic on canvas. 86.5 x 137 cm.

Courtesy of the Artist.

The critic Enin Supriyanto, who describes this disposition as “post Bali,” argues that what Mahendra Yasa seems to ask is this: “What is the meaning of painting today. If all the techniques, materials, styles, as well as iconographies…can be very easily reinstated on a canvas though realism and appropriation without requiring thought processes or subjective aesthetic considerations.”8 In one series, Mahendra surveys the masterpieces of Western art history in the Balinese Pita Maha style of painting which is mobilised to portray landscape. In his Jackson Pollock series in 2011, the abstract expressionism effect is faithfully depicted but in a mode so graphic it negates the gestural impulse of the style; the same is true of his Robert Ryman series in 2008, in which he represents whiteness photorealistically through lower contrast and careful chiaroscuro, not conceptually as object. In the face of this painstaking and elaborate project, we cannot help but wonder about the necessity of labour, and have mixed feelings of sadness and the sublime. Moreover, the aptitude and the diligence reinscribes Balinese as part of contemporary art through the appropriation of the traditional technique and the modernist object of Pollock’s drip or Ryman’s colour: the techniques of depicting flora and landscape transfigure the modernist fixation on the signature gesture and the facture of the inventive object. Alternating in this scheme are repetition and overinvestment, imitation and originality, trace and rigour, tourist art and contemporary art, the found image and the critical image.

In all these forays by Southeast Asian artists, the reflection on art history becomes a reflection on landscape, the evocation of place, its idealisation and corruption in certain discourses of distinction such as: nation, region, spirituality, gender, belongingness to an abode, and its role as refuge in the diaspora. This demystification of landscape ultimately translates into a sense of locality, something that hints at a possibility: that the spectre, or the unconscious, of the contemporary is the local that in turn significantly shapes the history of modernity and continues to haunt the present with the contingency of place, the entry points of modernity, and the histories of art in Southeast Asia.

This paper was developed from a presentation at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo 20th Anniversary Public Symposium titled “To Unravel Our Readings of History,” held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, November 1, 2014.