I

In November 2015, as chief curator for Fundación Alumnos47 in Mexico City, I invited Erick Meyenberg to create a piece for Proyecto Líquido. Desire. Proyecto Líquido uses diverse curatorial formats and aesthetic experiences to investigate the production and exchange of affections as axes of existence that provoke imaginary and tangible operations. Proyecto Líquido. Fear, 2012, focussed its interest on the fields of action indicated by these operations, and on their aesthetic, poetic and political consequences. Through the hybridisation of media, genre subversion and live art, Proyecto Líquido. Desire, 2016, continues this investigation through the commissioning of 11 artworks in public spaces of the Basin of Mexico, by artists Ale de la Puente, Tania Candiani, Erick Meyenberg, Sam Durant, Dr. Mayeski and The Luminous Resistance, Noé Martínez and María Sosa, Interspecifics, Bettina Wenzel, Wen Yau, Mariana Castillo Deball and Carlos Sandoval and Pablo Helguera.1

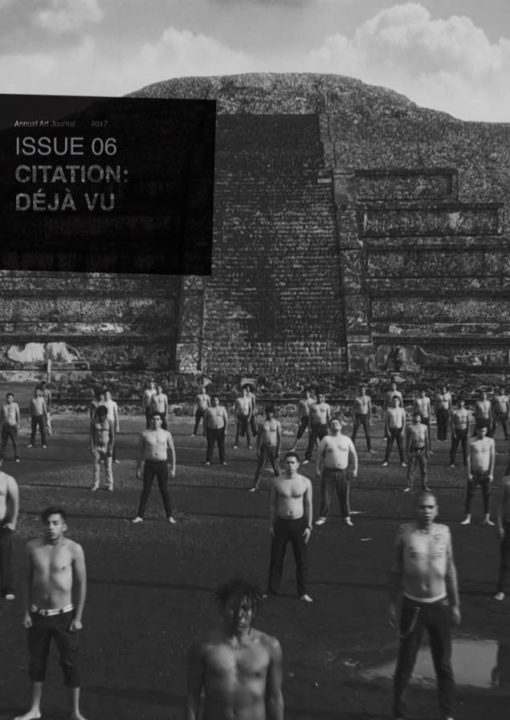

“We have never given a permission like this before.”2 Aspirants was a filmed performance at the ancient pyramid site of Teotihuacan, 4o minutes outside of Mexico City: a sound and video installation, with around 200 young men, that played on the double meaning of aspiration:

- to long, aim, or seek ambitiously; be eagerly desirous, especially for something great or of high value (usually followed by to, after, or an infinitive):to aspire after literary immortality; to aspire to be a doctor.

- to rise up; soar; mount; tower.3

Proyecto Líquido. Desire worked around many legal and administrative loopholes, and took place in sites where contemporary art had never been presented before. With Aspirants, the curatorial and production team managed to gather a group of young men who aspired to be football players, soldiers and drug dealers, to perform the exercise of inhaling and exhaling in front of the Pyramid of the Moon.

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Still taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.

II

‘It is estimated that around 200 individuals were sacrificed

at the same time on the occasion of the construction of the temple.

The majority of male skeletons have been interpreted as warriors.4

On November 9th, 2016, around 200 young Mexican men lined up on the Avenue of the Dead in front of the Pyramid of the Moon in Teotihuacan. An anticipant army. A choir of wet, mutant, preconscious aspirations. On that day, an epistemic mechanism was formulated generating deeply affective experiences in our contemporary warriors, the sacrificed, whose audacity and radicalism are tattooed on their chests close to the heart, in that tiny fold where desire lies hidden. Histories converged of men from a country whose myths no longer justify the disposal of souls, bodies and dreams. There no longer exists any ritual or bloodshed that becomes epic.

Coming from different areas of Mexico City, these men bring all kinds of experiences from the hazardous, precarious socio-economic conditions in which many live, along with their aspirations. In the Plaza of the Moon, they form an image that dislocates, in the national and international imaginary, the place this architectural complex has occupied for hundreds of years. While maintaining the militaristic nature of the Teotihuacan elite, the natural and artificial geometry of a space that contains other stone and organic bodies was experienced. Sky, hill, pyramid, human bodies in sequence and synchronism. A plane that devours its predecessor in a collective sentence that escapes to infinity.

We seek to add immaterial value to the dream of aspiring to a Mexico aware of its reality and its history.5

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Still taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.

III

Citation is a strategy that, through accumulation, works as a way of constructing histories and identities, by mobilising affects via narratives that can produce consensus or emphasise difference. Who we reference and who we acknowledge creates a political grammar that renders thought and knowledge visible. An interlocking of subject, time and place, evidence of the productiveness of intellectual and artistic labour, saturated with epistemological-ontological tension.6 Who said did what when. Citation practices provide frames of reference and legibility; they can be dedications and critical tributes that come from annotations and unfold into variations of the textual, the visual and the sonic. Yet, through repetition and not appropriation, citation can also blur its own skills for selection and interpretation, and fall into a dominant mode of citation practice: precluding disruptions necessary for the practical and theoretical shifts that lead to creative processes. Can one experiment creatively with citation, explore this epistemological-ontological tension that reveals power structures within any form of production? The following is an exercise in citation. I pile them up under the text itself in order to try and produce a second body of meaning. I try to use citations—as many as I can find in Erick Meyenberg’s artwork Aspirants, as well as citations the artist pulled together for the film we created, a 40-second loop—as a stratigraphic activity,7 as descriptive of a coming together of authorship, times and places. Of psycho-political and spiritual operations. Citation here, I propose as a writer, with thanks to the artist’s work, is a permeable structure of cultural imagery that can gather the forces needed to expose hidden ideological agendas. It all depends on who reads these citations, when and where—subject positionality changes everything. This stratigraphic activity of citation builds metaphors that may escape the image of Aspirants, metaphors that overflow and become excess, residue that may or may not become a narrative. Conscious citation practices offer new structures for historical events. They produce ‘something’: affect, materiality, relations, presentness, orientations, positions, attitudes. ‘Something other than.’ They are indications of accumulated social pulses. Citations are proof of circulation, of interrelatedness, of habits of thought or manifestations of discomfort, of doubt and vulnerability, of autonomy or of the pillars which convenience leans. Citations pile up everywhere, as past intensities and textures of the social mingle with the confusions of everyday materiality.

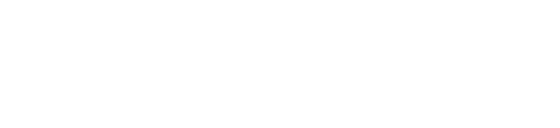

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Still taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.

IV

Citation is a practice I believe is related to what Craig Owens calls “the allegorical impulse.”8 A gap connecting past and present, where textual, visual and sonic memories are preserved and come forward. Adding through replacement of meaning by doubling texts, images and sound. To unfold and momentarily reveal the dissolution of meaning, the tiger’s leap,9 only to double back over. Transparency of signification or not, we are left estranged, left with fragments and ruins to be deciphered. Every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.10 Technique, perception, procedure. Reading one text through another. Fragmentary, intermittent, chaotic. Material depth. Through the frequency of citation, time is altered, metaphors are created and sometimes interrupted during their formation to advance something else. Longing, expectation, déjà vu. Familiarity through the overlapping of past and present. Also déjà vécu: having lived through something via the anticipation of that something. Images become other, pure potential, unstable and hopefully unpredictable. Through the reading of citation, another possible artwork is being formed. Otherness. Synchronicity of meaning. Citation varies perception and recognition. And works with density, as an element that allows to draw a network of relations between artists of different generations living in different countries; and adversity, a state of existence that connects artistic production with history and its local conditions. Citation can work here to question those relations and connections, producing open-ended debates. Citation practices are beckoned by ethics and, if congruent, may evoke the beauty within connectedness of thought, within pronouncement and announcement after borrowing, and the impact of taking from and making it your own.

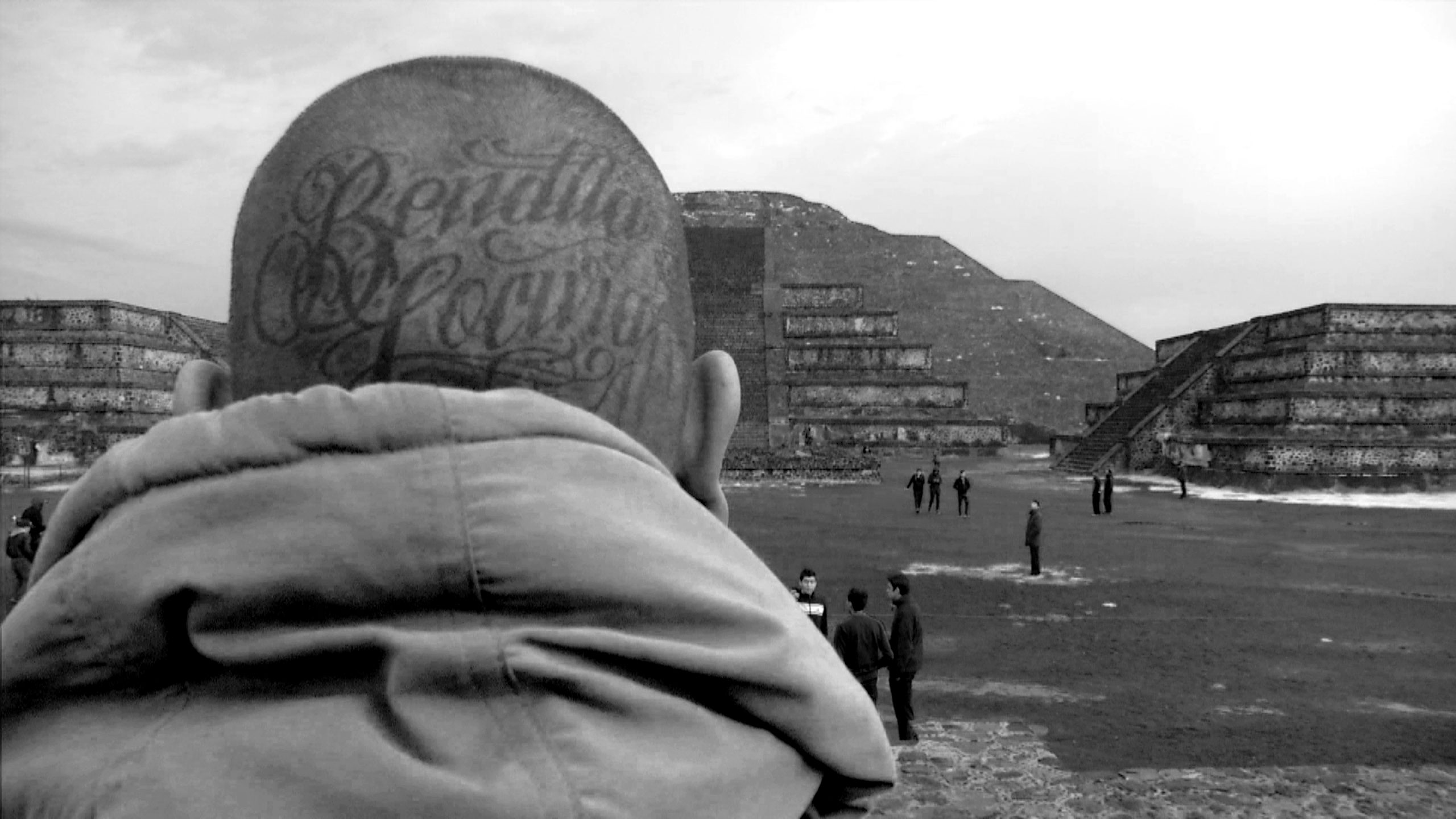

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Still taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.

V

Past11 and present combined to mirror12 the future. Time is distended into aligned bodies. Instances of mutation through inhalation, exhalation. Sky,13 hill,14 pyramid,15 human formation. Isolated coding producing estrangement. One paradigm for the allegorical work is the mathematical progression.16 Anticipation and desire biting into each other. Ouroboros or the feathered serpent.17 Architecture,18 landscape painting,19 film and performance falling and folding into each other. Like the breath: ascending, pausing, descending. As a wound that reveals the unravelling of its own suture. “… the crack being the very essence of human sensuality, it is what drives pleasure. Likewise, when we perceive death, our breath is taken away, in some way, at the supreme moment, we stop breathing.”20 “Allegory concerns itself, then, with the projection – either spatial or temporal or both of structure as sequence; the result, however, is not dynamic, but static, ritualistic, repetitive.”21 “What happened did indeed happen, but there is something that only happens if it happens in full, perpetual present in rotation.”22 “Allegory superinduces a vertical or paradigmatic reading of correspondences upon a horizontal or syntagmatic chain of events.”23

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Still taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.

VI

Alejandro Sarabia and Natalia Moragas note: “Teotihuacan is one of the most important archaeological sites in Mesoamerica. Scientific investigations on the site have opened the way to knowledge about and understanding of, the different social processes involved in, for example, the economic, urban, political, architectural areas during the development of the Early Formative period in America.”24 This influence determined the social structure of diverse cultural fields throughout the Classical and Post-Classical eras in the Mexican Altiplano that affected the organisational apparatus of succeeding civilisations, creating an imaginary of pre-Hispanic civilisations that extends to the present-day and forms part of the strong rise of national identity.

Teotihuacan therefore interests us as an area in which to deepen, through art and education, our understanding of these social processes that have shaped both the identity and visual representations of a society located in the Basin of Mexico. A group of young Mexicans and their different aspirations – aspirations directly linked to the social, economic, religious, cultural and political history of the Basin of Mexico, and to Teotihuacan as the centre for the production of knowledge, power and identity – are the means by which this interest may be fulfilled.

Teotihuacan and the Pyramid of the Moon permit a more profound look at the history of this ancient city and a closer analysis of its significance to contemporary Mexico. We are reviewing the Spanish chronicles of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, Francisco Javier Clavijero and Fray Juan de Torquemada, of travellers and scholars such as Humboldt and Madame Calderón de la Barca, of Charnay, Chavero and García Cubas, together with modern archaeologists such as Leopoldo Batres, Manuel Gamio, Alfonso Caso, and Jorge R. Acosta. We are also revising more contemporary research led by Saburo Sugiyama, Leonardo López Luján, Rubén Cabrera and Lina Manzanilla, among others. We need to understand the year 1917 as a key moment in time when past and present were integrated into an anthropological project with the founding of the Department of Anthropology by Manuel Gamio for the interdisciplinary study of the ancient and contemporary population of the Valley of Teotihuacan. This is essential to our artistic proposal, our goal also being the transdisciplinary (art, education, history, anthropology, philosophy and archaeology) integration of the past and present into one work of art, thus significantly contributing to the production of our country’s cultural heritage through serious study and inter-institutional collaboration.

Much has been written about the different types of research on the Basin of Mexico – architectural, urban, social, anthropological – for generating urban, social, political, public law, participatory development programs, projects, etcetera. In addition to generating government policies for solving current needs and emergencies in the area, the Basin of Mexico also embodies experiences and the ways in which public, urban and cultural policies, in the exercise of human action, are manifested.

All these actions shape the landscape of the Basin of Mexico. The clear manifestations of the image that is projected in public spaces show the effect of these actions. Inhabiting a city is the effect of modelling space and constructing the landscape according to the image of our desires, our policies and our dreams. The construction of a landscape requires the ability to stimulate the image of a desire and make it a reality.

Proyecto Líquido. Desire evolves from this condition: to catalyse our image in space, to build a landscape that measures up to our desires. An understanding of artistic action and artwork as reflections of desire in the space we inhabit, represented through a series of works of art presented in public spaces within the Basin of Mexico.

Taking as one of our references the academic article by Alejandro Sarabia and Natalia Moragas on the investigations carried out at Teotihuacan, we propose a project that integrates history, archaeology, identity, the building of a nation, youth, and our historical present: “To speak of Teotihuacan is to consider the development of the socio-political complexity, consolidation and development of the urban phenomenon, the expansion of the ideology and the religion of a culture into a macro-regional concept, the design of long-distance trading networks, and other issues.”25

Over a century after its foundation, the ancient city of Teotihuacan has created an identity defined by its architecture and nourished by the experience of living in it; the organisation of this city with its talud-tablero composition establishes the vision of an infinite path, an organisation, and a type of orderly thinking. The Avenue of the Dead, located South to North, makes up the cosmology of the ancient inhabitants in the landscape of Teotihuacan. At the end of the Avenue lies the Plaza of the Moon whose principal architectural structure is the Pyramid of the Moon. Framed by the natural landscape of the area, the pyramid was built during the Tzacualli phase and is oriented and aligned towards the Cerro Gordo Mountain.

José María Velasco, Pyramid of the Sun, 1878. Oil painting.

Painted from the Pyramid of the Moon in Teotihuacan, Mexico.

On display at the National Museum of Art, Mexico City.

Image courtesy of MUNAL (Museo Nacional de Arte).

The event we are proposing involves filming 200 people in a pyramid formation, within the Plaza of the Moon, mirroring the Pyramid of the Moon. The reason we want to work in Teotihuacan is as follows: our interest in the site stems from our desire to deepen, through art and education, our understanding of the social processes that have shaped the identity and visual representations of a society located in the Basin of Mexico. A group of young Mexicans and their different aspirations – aspirations directly linked to the social, economic, religious, cultural and political history of the Basin of Mexico, and to Teotihuacan as the centre for the production of knowledge, power and visual culture – are the means by which this interest may be fulfilled. We seek to add immaterial value to the aspirations of a Mexico that is aware of its reality and its history. We are also interested in developing, in our team of 200 applicants, knowledge about and awareness of what was and what is Teotihuacan.

The Pyramid of the Moon comprises seven superimposed buildings decorated with ritual and sacrificial deposits that celebrate and consecrate each new stage in the construction of the pyramid. These findings lead to a reconsideration of the systems of government and religion at Teotihuacan. Anthropologists, Lawrence Sugiyama and George L. Cowgill (who is also an archaeologist), are two important references for the project due to their in-depth investigations into the architecture-landscape-body relationship, and we are interested in exploring their ideas about ritual and sacrifice from a contemporary perspective.26 Both these researchers mention the importance of young men to the consecration of the city.

Part of our research is also based on the ideas of Octavio Paz in relation to the Mesoamerican pyramid:

The geometric, symbolic representation of the cosmic mountain was the pyramid. The geography of Mexico tends towards the form of a pyramid as if there existed a secret but obvious relationship between natural space and symbolic geometry, and between the latter and what I have called our invisible history… the pyramid is an image of the world; at the same time that image of the world is a projection of human society. If it is true that man invents the gods in his own image, then it is also true that he finds his likeness in the images that the sky and the earth offer. Man makes the human landscape human history; nature converts this history into cosmogony, the dance of the stars.27

Besides the experience of living in it, Teotihuacan is nourished by the discoveries, documents and research by historical figures such as Leopoldo Batres, Lorenzo Boturini, Brantz Mayer, Antonio García Cubas, Manuel Gamio, Gumersindo Mendoza, and José María Velasco, among others. Velasco documents the area for scientific purposes, but the results of his documentation built a vision of the landscape as a symbol of identity, still strong, that became a myth of nation. For Erick Meyenberg, the artist, and for me, the curator and researcher, Velasco’s landscapes in the Museo Nacional de Arte (National Museum of Art in Mexico) have fed the vision for our project. In 2012, Dr. Peter Krieger, renowned researcher at the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Institute of Aesthetic Research, National Autonomous University of Mexico) published Transformaciones del paisaje urbano en México. Representación y registro visual (Transformations in Mexico’s Urban Landscape. Representation and Visual Record), in which he reconstructs the history of our city and part of the Basin using carefully selected visual material from the National Museum’s Foundation.28 In this reconstruction or eco-history, José María Velasco’s visual investigations are an essential part of modernity’s imprint on the landscape of the Basin.

Just as Velasco’s aesthetic and scientific views on the area provide us with information, the landscape and perspective of nationalism later resulted in the creation of a new way of visualising the area. Artistic expression in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through the middle of the 21st century asserted its influence on Mexican cinema, which is why another fundamental reference for the aesthetic research of our proposal is cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa’s work:

I think that by incorporating cinematic photography into the Mexican visual arts movement, I incorporated the Mexican landscape in the form of the equilibrium, chiaroscuros, skies and dramatic clouds that we have here, and all that in the service of cinematography in order to obtain a very Mexican image in black and white photography…29

Figueroa’s visual shots assert the type of influence and aesthetic created by the artistic movements of the time, and highlights man’s desire to situate his longings within a framework comparable to nature. Figueroa extols a vision of Mexico, filled with desolate spaces that reverberate with nationalist tones. Obsessed with the emblematic, he brings together visual rhetoric and national discourse. This visual discourse is largely fed by the desolate landscape of the Mexican imaginary. Figueroa’s cinematography is placed at the service of the construction of the national imagination similar to the landscapes that Velazquez painted of Teotihuacan. The eye feeds the vision that man has of the world, the perspective held by inhabitants of the Basin during that time regarding their identity and their geographical, political and cultural relationship to the Basin of Mexico. Thus, Erick Meyenberg seeks to comment on the construction of the identity of this region, the Basin, by means of these four axes outlined for the creation of a nation: history, landscape, city-state (Teotihuacan), and film, as the building blocks of myths.

The artist reflects on the construction of the Pyramid of the Moon in reference to the Cerro Gordo mountain because, in addition to being thought of as a construction that alludes to the goddess of water and fertility, it is, from an aesthetic viewpoint, a construction that is clearly linked to the geography of the place. This type of construction, friendly towards and consistent with the landscape, indicates the strong connection that the ancient peoples had with their environment. The amount of effort required to build such a monument only registers when you think of the time it took and the number of men needed to perform such a feat. This artistic action is related to the desire of all men to build and modify their territory.

The proposal consists of a film recording of the group of 200 young men in formation in front of the Pyramid of the Moon: the youths, there by direct invitation, will be filmed performing the subtle action—inhalation and exhalation—that opens up enquiries into desire, and the aspirations of the youth of our country. The image pays homage to the site and its importance in our contemporary lives. It is also an image of the identity of the young people of Mexico: one that stems from the ancient inhabitants, architecture, geography and landscape, juxtaposed with the need to make visible their aspirations for a better life. To quote Paz: “Living history as a rite is our way of accepting it.” This is what we want to achieve. A ritual that speaks of our history.

Rarely does an artist have the opportunity to present their work in a space so full of tradition and history. This film prioritises the tangible heritage and therefore Teotihuacan will not be affected. We are sure this will be a unique piece of work in the history of Mexican art by recognising and paying tribute to this unique site, and promoting the preservation of the historical, symbolic and cultural memory of our country.

VII

Filmed action Aspirants30

The project seeks to compile the aspirations31 of young Mexican men through a film that demonstrates the violent and precarious conditions experienced by the Mexican population today. At the same time, the film highlights their desires and dreams for a better life.

Profile

200 Mexican men between 18 and 25 years of age who live in Mexico City and the hazardous socio-economic conditions of the metropolitan area; men who hope to find more security through drug trafficking.

VIII

To all participants32

At a time such as the one we are living in today, in a country like Mexico where citizens ‘disappear,’ we need young people who, through their presence and attitude, make the population of Mexico aware of the reality and urgency of their desires and aspirations for a better life; and we want to bring everyone together to make this clear once and for all.

The symbolic action you are about to perform, and we would like to say how deeply grateful we are for your presence and participation, will attempt to unite this collective dream. However symbolic it may be, it requires real people with real intentions, and this is the reason why we have summoned you all here. We ask for your total concentration and that during the filming you focus your mind and body on that dream of a better life to which each one of you aspires. May the conviction that change is possible be perceived throughout your whole body!

The intention of this small action is to relate the history of our country to the present, to you. It involves a military formation in front of the Pyramid of the Moon and the convocation of a collective breath, referencing an army of young men from Teotihuacan who were all sacrificed at the same moment hundreds of years ago.

Please do not overestimate the magnitude of small actions. However simple they may seem, we are convinced that this small action will arouse deep reactions in the people who see it. But in order to achieve this result as powerfully as possible, we need your complete cooperation, your absolute concentration, and for you to work together as a great team, as a great army.

We have nothing further to say other than thank you for your decision to participate, and we hope that this will also be a great experience for you, as it already is for us.

Many thanks to everyone,

Erick Meyenberg and the team at Fundación Alumnos47

IX

Aspiration Exercise

By Nadia Lartigue (Choreographer).

The exercise consists of breathing together. It’s very simple, but as we will be close to 200 bare-chested people, we must try to synchronise our breathing. A person will be in front to help guide the action and tell you when to inhale (lift the arms) and when to exhale (lower the arms).

Below is a brief description of the action.

Initial or neutral position

Standing, legs slightly apart (just past shoulder height), arms held down the length of the body with the palms of the hands turned towards the thighs. Looking to the front, a serene and present face. Lips relaxed.

Exhalation (10 seconds)

The next time you inhale, slowly let the air out through the slightly-open mouth, producing a subtle blowing sound between the lips while imagining a thread of smoke coming out. This movement is accompanied by the gaze moving diagonally down to the front and down (45o) as you exhale. Relax the shoulders and let them drop gently forward, feeling how your hands fall five to 10 cm down along your thighs.

Inhalation (10 seconds)

Imagine that the air is coming from your feet and going up to your head. Begin to slowly draw in air through the nose, counting up to 10 seconds. During that time, inflate the ribs and chest upwards and sideways while bringing your gaze up from diagonally down and to the front to diagonally up and to the front (45o). Your shoulders open (without raising them up to your ears), while the expression of your eyes is that of someone looking at the distant horizon with great seriousness and conviction.

Try to hold the air up for another five seconds without moving and with a very firm expression.

Repeat the exhalation and inhalation for 10 seconds.

When everyone inhales and exhales at the same time, we will attain the image of one single body that breathes and generates one same energy.

Aspirants

The exercise consists of breathing together. It’s very simple but, as we will be around 200 bare-chested people, we must try to synchronise our breathing.33

One of Erick Meyenberg’s aspirations was to create, through his art piece, an environment of sound through 200 men breathing, inhaling, and exhaling in unison. Though it seemed like a simple action, it brought 200 young people to where the Avenue of the Dead ends. It is a simple action that leaves something inside your body: a desire, a dream, a failure or an aspiration. An aspiration that is sown within the breast of each of these men; a symbolic action that begins with a discourse on a generation’s circumstance, and evolves into an assertion of the will’s desire.

Top

Erick Meyenberg, images taken from Google for open call in October 2016.

Right

Erick Meyenberg, Aspirants, 2016. Video, 40 seconds, loop.

Filmed action in Teotihuacan for Proyecto Líquido. Desire.

Stills taken from video by Julien Devaux.

Images courtesy of Fundación Alumnos47.