Rirkrit Tiravanija is an artist who can easily pass through different fields of cultural knowledge. Born in Rio de Janeiro, and based in New York and Chiang Mai, he speaks of being Thai, of Buddhistic culture, of activism, democracy, being a host or not being a host, making dinner, friends, strangers, an artist making Art and not making Art, a nomad.

In recent years, Rirkrit’s work have poked holes in our beliefs in epistemological realms. Some say one approach to achieve that is through science fiction. And perhaps this begins with H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, an idea that time is not necessarily linear, expressed as far back as 1895.

Inspired by this, Rirkrit produced in a 2014 exhibition, Time Travelers Chronicle (Doubt): 2014 – 802,701 A.D., at STPI Singapore. His work centred on investigative and fictional logs of time travel chronicles – travelling through space measured by time. In a sense, these works (as well as in his 2017 exhibition Exquisite Trust) are akin to ‘maps’ (“the vastness of time collapsed into a single encounter”)1 cluttered with insignas of pop culture (and today all culture is pop). Whether in monotype print, or created with the cast paper, or 3D printed, there is a tortoise, a hummingbird, SpongeBob, bonsai plants and yes, a martini glass – with an olive on a stick. There are unfathomed lines of connections between and among the many signs, and we may have to wear a helmet (created by future technologies) to help us decode them.

Or eschew the syntax of things.2 We are in SpongeBob’s “surreal realm of Nothingness.”3 And in that surrealness, that dream, “To wake up under the tree. Again.”4 A prediction and predilection of SpongeBob. Again. A déjà vu. A Time cycle. A repetitive blip on the radar.

Until then, according to Rirkrit, the present Utopia is chaos. “The further one travels, the closer one returns to doubt.”5

To be a traveller, to leave, to roam, to arrive (maybe), to be a nomad and, as such, exist outside philosophical thought.6 The ‘math compass’ or ‘sextant’ are relegated to the role of relics to be displayed as artefacts in a museum of the traveller’s chronicles: a déjà vu of a past encounter.

The chronicling cannot be separated from the chronicler – positionalities in the web of experience. Self-conscious, the chronicler safeguards the quest for meaning; is there an ‘I’ in the ‘who am I?’ The quest is in constant calibration either with or against the politics of vision.7

His work punctures comfortable force fields of epistemes, attempts to break free of them; introducing the familiar with the unfamiliar making it familiar again. ‘Citing’ cultural practices and imageries, and giving them these strange new contexts, inciting us to calibrate and recalibrate, so as to extend beyond or even recreate what we ‘know.’ Never settling into any field, which perplexes us, because it recalls ‘The Truth is out there,’ pulled into tension with ‘I want to Believe,’ X-filean8 clichés that dog us as we manoeuvre and fumble through our existence. The pull of the Utopian, the unfamiliar, strangeness effected by a sense of déjà vu.

The following interview9 gives an insight into Rirkrit’s thoughts, though it can only serve as oblique references to his work, as ‘dreaming’ and déjà vu can only be shadows or echoes, uncertain.

Rirkrit Tiravanija (b. Buenos Aires, Argentina) is a Thai artist, based in New York, Berlin and Chiang Mai, and is widely recognised as one of the most influential artists of his generation. His work defies media-based description, as his practice combines traditional object-making, public and private performances, teaching, and other forms of public service and social action. He is often cited as lending to critic Nicolas Bourriaud’s observations on and definition of Relational Aesthetics (Paris: Les Presses du réel, 2002).

Tiravanija is on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University, and is a founding member and curator of Utopia Station, a collective project of artists, art historians, and curators, which was seeded in Venice Biennale in 2003. Tiravanija is also President of an educational-ecological project known as ‘the land foundation,’ located in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

In recent years, he had exhibited twice in Singapore at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI): in 2014 with Time Travelers Chronicle (Doubt): 2014 – 802,701 A.D. and in 2017, in a group exhibition Exquisite Trust.

Susie

In your food events, what does the preparation and serving of food facilitate? I recall how you and my M.A. classmates took over the preparation — including the marketing — of food that you served at my place way back in 2006 or 2007 in Singapore. All I could do was enjoy the process and the food. What you did then was circumnavigate through all the classmates’ homes to engage in this process which involved, at times, family and cats.

This was obviously very different from enacting this event in the “gallery.”

Rirkrit

Well, my initial interest in food and the circumstances surrounding cooking—the preparation of food and the social relationship—[stemmed from] my interest in questioning Western colonialist hegemonic prescription of otherness. I was looking at encyclopaedic collections of museums in the West, i.e. the Metropolitan Museum in New York; the Museum of Natural History in New York; the Field Museum in Chicago; the Art Institute of Chicago (where there is a large holding of Thai artefacts), [and] finding myself asking, “What are ‘they’ thinking of me, when ‘they’ look at these artefacts, and am I in that position?” The position of otherness, the position of the object, of the process without knowing. How is the centre circumscribing the periphery and assigning positions, assigning values, naming, categorising, making representations of the unknown; and pressing their language into knowledge, into history, into cultures?

I was interested in, what I assigned to myself, the need to retrieve culture, to retrieve my identity, from the assigned hegemony; and in [using] the process of making dinner, making cuisine, making (in my own image) my daily circumstances, as ways to make different readings, different meaning, differentness as the otherness.

Of course in my culture (Thai), and perhaps in many cultures, the situation of living, the conditions prescribed in the living condition are visibly (have been, and perhaps now in flux) prioritised over the objectness of life. In Thai culture, togetherness is practised without much apprehension, without much negotiation, as our values are not assigned to the external (objectness) but rather to the internal. The spatial value of private and public are [neither] assigned nor given, property (was) not demarcated with centres and peripheries. We enter into the spaces of otherness without feeling the others apart, but rather we enter into togetherness. We give what we have without the expectation of reciprocity, without return, as the return will always come in the future (afterlife, or next life, perhaps).

So, it was not about making Art; it was not about having to act or make or produce Art, but rather to act and be in the moment, to do and be in the nature. Perhaps, in the West, making and being and doing and living in a particular context, all those movements can be circumscribed as Art. The everyday as I live it becomes my retrieval (of culture) of myself within the hegemony forced upon my existence; to live in the everyday, the normal, the ordinary, the unspectacular, is the resistance to become commodified.

Susie

There are many ways of looking at this as an “art event,” and yet not. What are you thoughts about this?

At the land foundation

Courtesy of the artist

Photo: Francesca Grassi, 2004.

Rirkrit

So, yes, I’d rather be eating and drinking with students, with friends, with strangers, than [making] Art.

Susie

Could you speak about the role of the host in some of your projects?

Rirkrit

I am not at all interested in [being] a host, I think we are all hosts and we are all guests. Hosting implies one giving and another receiving; as I have mentioned above, I am interested in togetherness and, in that, there cannot be hierarchy, there cannot be the other. But I like the biological host, which implies carrying parasites, carrying otherness within, making a destabilised whole.

Susie

From social practice to civil protests, based on images that are culled from mass media, can you speak about the protest drawings and how it relates to your other projects –Demonstration Drawings (2006) for instance?

Rirkri

As mentioned, I am interested in destabilised centres, it’s an interest in representation, [interest] in the known versus the unknown, the mass versus the few, the receiver and the transmitter. Perhaps it is [because of the] confluence of circumstances that people (the mass) are becoming more visible. The faceless now have Facebook, that one is instantly “liked,” the confluences of the private becoming public. Perhaps the language (usage) needs to also become more resistant, more poetic and less self-centred. The condition of a demonstration is about the poetics of representation, of voices, of refusing to be identified and named by the centre, by the hegemony.

Susie

Your practice feels very democratic and non-hierarchical, how did this kind of practice come about?

Rirkrit

Perhaps growing up in a Buddhistic culture, and I mean culture rather than religion. The religion is still hierarchical and the assignment of power is important to those in the religion when, in fact, it is only a practice. It is about circumstances and how one can live best under those circumstances, to practice (what is that anyway?) and raise oneself beyond oneself. Democracy is (presently) like [any other] religion. We are all asked to conform to the ideal of such an idea, as it is used and interpreted by the hierarchy, the hegemony; as an alibi to circumscribe us and corral us into believing that we are living without hierarchy, without hegemony; that we have a voice and that we are entrusted with the rights to speak and be heard. But who is listening and who is speaking? We can see and hear that we are living in the delusional sea of Democracy. Access to speech is meaningless when that speech is just a tweet of abbreviated thoughts.

Susie

Tell us about the land foundation project and your community activism. What is the current status? Unfortunately the online website is rather limited.

Rirkrit

The land foundation is ongoing; the rice is growing and mangoes ripen on the trees, everyone around is active and projects are in the process of being realised. It’s difficult to describe a process, or a length of time which we have no interest [in measuring], or [defining]. I suppose, we would like it to be itself, have its own life, perhaps the land (always without capitals, purposefully) is a good example of a host. It is a host of others, a host of organisms which coexist without hierarchy, without order. It hosts parasites without the fear of losing itself, it does not intend to represent but is, in itself, a representation. The lack of information is as intentional as it is unnamed or uncapitalised. It is and can be what we want it to be [as a collective], and what we want it to be for ourselves. Perhaps it is a state of being everything and nothingness.

Susie

For your work, DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY, what is the “same sky?” and how do you posit the question of difference?

Rirkrit

Right now in the world we have a problem with difference. [The] reason why we are not in a better world is [because we are] not understanding difference in a big way. If we think we are supposed to be in better place because we have gone through civilisation and nightmares; if we [should] be in a better place and we are not, we have to ask why and the ‘why’ can be answered by Donald Trump. Because we are still voting for people like Donald Trump. Giving power to people who don’t really care about [a] better world. They only care about themselves. That’s everywhere. It makes problems in Thailand look small. We thought Populism is such a huge problem; it really divided the country. Now the [world’s] Number One Democracy is being shredded by stupid idiotic ideas. Humanity is incapable of betterment. Consciousness doesn’t go further.

Susie

What is Utopia to you?

DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY

Art Basel in Basel 2015

© Art Basel

Rirkrit

– Chaos.

Susie

Not the reverse?

Rirkrit

Western [ideas] of order and sameness, and maybe Singapore’s as well, is wrong. It is not possible to make [humans] conform to structure. That’s not Utopia. Utopia is everybody being different and being able to live together. Chaos; living in chaos and not blowing up and killing everyone – that’s Utopia.

Susie

This idea of living together and this idea of sharing…

Rirkrit

It’s not about sharing.

Susie

We do share the sky?

Rirkrit

With Donald Trump there won’t be a sky, there will be a big ozone hole. We will all burn to death. [For him] to be put in a position of a world leader and to have no compassion… if there was any inkling of it, it is all pretence. [That’s] how world war starts. They do not see a future, the future is false. To say I am doing this so that America becomes great again. What kind of reality is that? To be ‘great’ over whom?

We need to reconsider what is the sky we are living under, and there will be [oppositions]; there will be people coming together. For the people coming together, they have to understand why it’s not just a reaction, not just ‘against’ something. It has to be ‘for’ something. That’s what [we have to] make sure we understand. Everyone has different issues they are concerned [about], everyone has different realities, but in the end we all have to think about each other.

So, if you thought that we could make a dinner, and everyone could come and sit and eat together, and talk to each other, and that would change the world; and well, it hasn’t really changed the world, [then] what does it mean? It means we have to keep going, we have to keep doing it—keep pounding into their heads that we have to sit with other people, understand that difference and respect that difference, and smells and sounds and – codes.

DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY

Art Basel in Basel 2015

© Art Basel

Susie

Do you think success [is also dependent on privilege]? When you say making dinner and all that – who is able to do that?

Rirkrit

To have time to think is a privilege. A lot of people do not have time to think because they have to survive. That’s what I am saying—because everyone is coming out, reacting, and trying to resist. But one has to understand that, maybe, it’s not about resistance but more about understanding the other. You are not there to think for someone else.

Susie

As an artist what is your role?

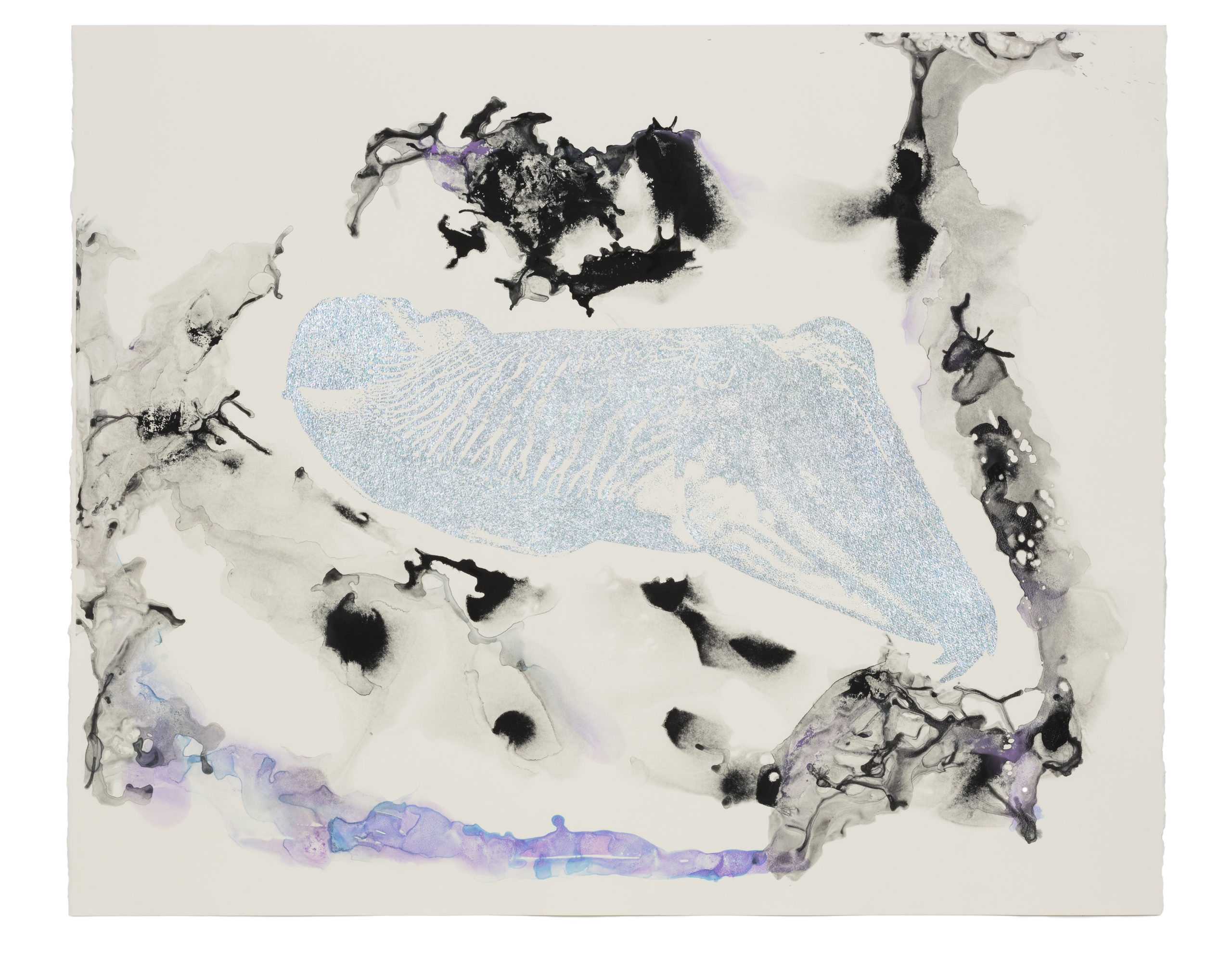

Untitled 2017, (bodhisattva appears in crimson tide), 2016.

Water-based monotype, metal foil on Saunder’s paper, 114 x 140 cm.

Artwork produced at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore

© Rirkrit Tiravanija/STPI.

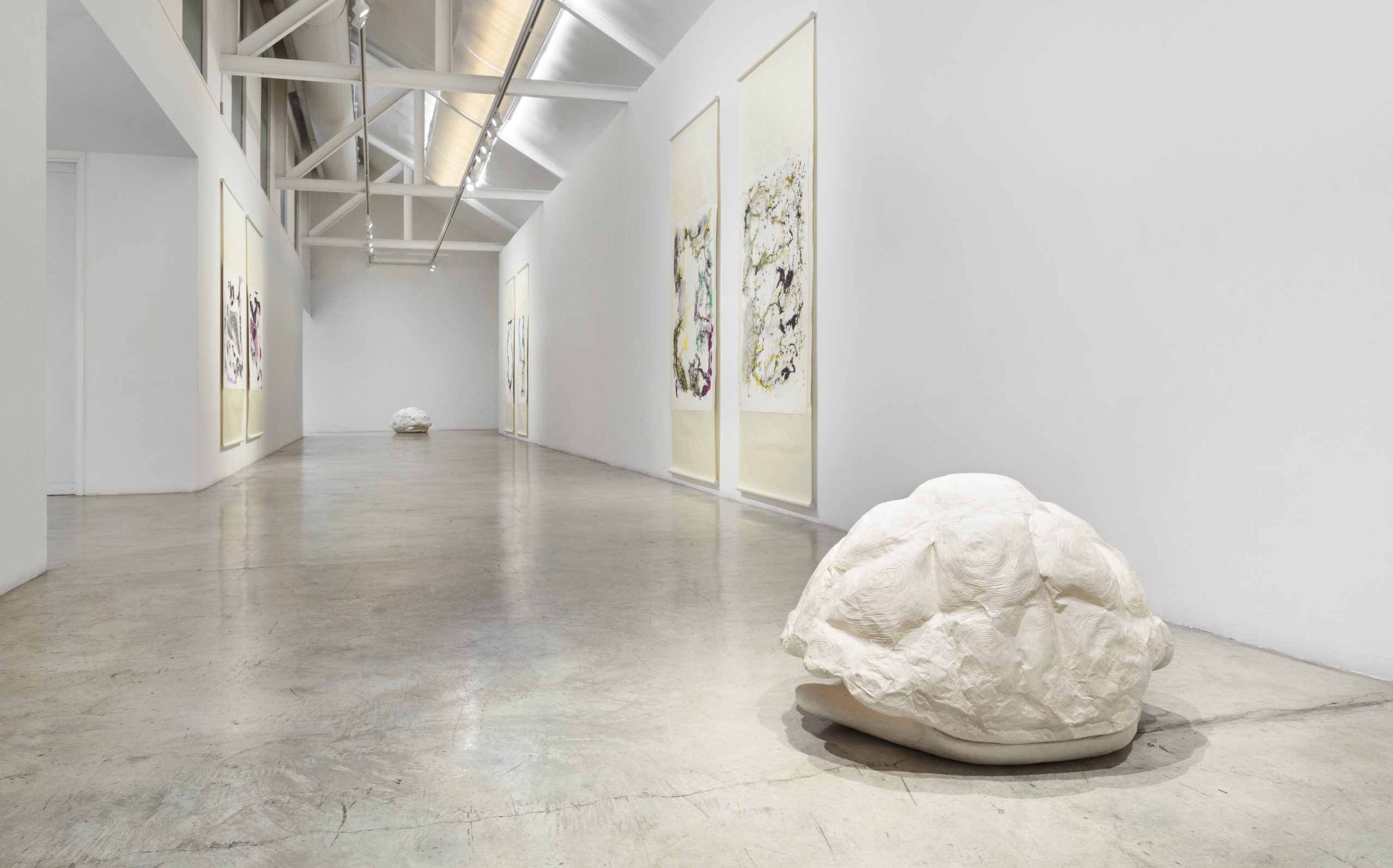

Installation images of “Exquisite Trust (Blindly Collective Collaborations)”, STPI Gallery, 2017.

Courtesy of STPI. Photo: Katariina Traeskelin

Untitled 2017, (bodhisattva reflections in the silver seas), 2016.

Water-based monotype, metal foil on Saunders paper, 114 x 140 cm.

Artwork produced at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore

© Rirkrit Tiravanija/STPI.

Installation images of “Exquisite Trust (Blindly Collective Collaborations)”, STPI Gallery, 2017.

Courtesy of STPI. Photo: Katariina Traeskelin

Rirkrit

My role is to sit here and make statements that will get into the magazine [laughs]. And hopefully more people will read it. [The] life of an artist is to live [out those statements] and maybe, one day, people will look at it and realise that it’s possible. I always think one has to…I’d like say I’m living the way I talk. Because a lot of people are not living the way they talk. So that is my concern.

Susie

Let’s get back to food as metaphor, in this case – your relational work. At the last we touched on non-hierarchical and democratic ideas.

Rirkrit

I’d rather say ‘open.’ Those words are understood as if they mean more, and actually they are just words. What I’m trying to say is it’s more about accepting. Accepting the other.

Susie

In terms of the gallery, and in terms of practising art in the gallery system, who is the other?

Rirkrit

I’m in every other system; I don’t think I’m in one system. The gallery is one system to use, to put things out. I don’t think of it that way. The ‘other’ is everybody like myself. It’s not about [the] gallery or not [the] gallery or street or museum. Everything is the same. [I work with a gallery] and, actually, galleries support a lot that is not supported outside of it. A lot of ideas come out of [the] gallery, a lot of art comes out of people being supported by galleries, so I don’t see it as being you know… it’s how you use it. But I don’t see the point [of it being] the only system. I do many things that nobody sees; it doesn’t mean I have to make it visible.

Susie

At the beginning of this interview you were saying, “making normal again.” Does that mean not having the (and this is my word) trappings of the gallery?

Rirkrit

You are only trapped by yourself; it’s not the gallery, it’s not anything, it is just yourself.

Susie

Bodhisattva coming out here [laughs].

Rirkrit

You are the trap, not the gallery and, again, it’s about how you use it. [There are] galleries who try to do very good things and promote very good things but, of course, it’s not the only way.

Susie

What are the other ways?

Rirkrit

The other ways, for me, are to do everything you can do, if possible; or not do anything at all. There are reasons to do things and reasons to not do things. That’s all the other ways.

Susie

With you, is everything so well considered?

Rirkrit

No, I am not enlightened [laughs]. We are always trying to figure things out. Some people try to figure different things. I’d like more balanced things, a more balanced life. On the other hand, if I get to say things because people want to have someone say something, then I would say it. I mean, personally, I would like to sit under a tree and not speak to anyone. But at the same time, if there are things to be said and to be done, and you can do it without killing yourself, then you should do it.

Susie

The point I’m trying to get at, is whether there is an inside and outside of [the] gallery for your practice.

Rirkrit

Why would you want to have an inside and outside? No, I mean there is always an inside and [an] outside, but it does not mean that it’s divided. You live a life; you can’t split your life. If I’m making dinner for 100 people, it doesn’t mean I’m making a show; I’m just making dinner for 100 people. Actually it’s easier to make dinner for 100 than dinner for two. [If] you are going to make something, you might as well make it for more. If you are going to put in energy to make something, it’s the same energy. So it’s harder to make just for two, because you use as much energy, and then there’s less. So I don’t see it, I don’t make the dichotomy. I think it’s like, the world thinks in dichotomies but that doesn’t mean one needs to.

Susie

Does it apply to your life, of being born somewhere else and being in Thailand now. Do you feel in that sense of being categorised, or demarcated? At some points, you identify yourself as a Thai national and at some points, hearing you speak, it’s as if your position is as an American.

Rirkrit

No, I don’t feel that. I criticise everything [laughs]. I speak about America because it’s what everybody is measuring up against, you know? Or Americans like to think that everyone is measuring up to them. But no, I don’t privilege it.

I’m reading Édouard Glissant. He’s talking about a kind of nomadism as a kind of creative act, and creativity being, a relational thing. So he’s coming form Martinique, a former colony [of France], and he can’t be bothered to resist speaking French, to fight the colonialist. Because for him, language can be used creatively and it’s creativity that makes the difference. At least that is how I’m interpreting it. Which means it’s true—I can be in whatever structure and I would, just say, be creative; use it in a way that is not oppressive. The book is Poetics of Relation. He’s from Martinique, the Caribbean. It’s about being Creole. It’s about creating another language out of whatever exists. And, one could say, in the context of proper language and proper structure, that it’s an abuse of language. But, rather than that, one could also say that abuse can be creative input. So language is changing.

Susie

How about Singlish, using English badly?

Rirkrit

Yes, but that’s an identity formation. It’s not about [creativity]. It’s more about what’s the attitude. If you are using [it] creatively, you are not oppressed. If you use it because you are oppressed, then you are oppressed.

Susie

Do you think we are all nomads today?

Rirkrit

We could be because we have access to everything. And I don’t mean we have to move. We can go everywhere without moving. We are trying to walk around a frame and we don’t get an answer. That is the point. We don’t want to pin everything down. You can’t. You have to understand you are always moving. [That’s] always the problem with Western philosophy: they think they can pin everything down, and then they realise it’s a mistake, it’s not true. And there’s always another truth.

Susie

Which becomes a contradiction.

Rirkrit

Not a contradiction, we are not frozen. Again this comes with creativity. If we are no longer creative, we would not have a future.

Susie

What do you think is the objective of creativity?

Rirkrit

To not be dead. To be alive.

Susie

To be alive, as in, to have a reason to be alive?

Rirkrit

To be alive means to accept change and to move through that, and that’s part of the problem of not understanding difference. If you don’t understand change, you can’t understand difference. You are changing all the time and everything else around you is changing. Therefore, they are not going to be the same.

Susie

And here, we can go back to Donald Trump.

Rirkrit

We can’t expect White and Germany to rule the world all the time and be happy with the best jobs, which is what Trump says he wants to have again. It comes from not understanding difference. And if you don’t understand difference you will never make a better world. Because [Trump] just wants to make the world a picture that [he believes] in. Which is not even true. The 50s and even 60s were not the best of times; whatever they thought was the best of times were not. It’s a fragmented [idea of] reality. They were blowing nuclear bombs on paradise. That’s not making a better world. I have to think a lot about why we are trying to do anything. Why? What for? [I] used to say, as [an artist], I would like to make people more conscious. Actually, people are not becoming more conscious. There’s more knowledge, there’s more information, but they are not becoming more conscious. They are becoming dumber. Why? I’m not blaming anyone, I’m just asking “why?” Maybe when we are thinking about a better world, we are just thinking about ourselves.

Susie

So thinking of a better world brings us back to the idea of a Utopia.

Rirkrit

Well, it’s about thinking of others, maybe it’s about thinking holistically. You can’t think in fragments, you have to think about the bigger picture.

Susie

It’s difficult to pin down something like that. It’s rhetorical.

Rirkrit

No you don’t pin it down, you just do it.

Untitled 2017, (a drop in the drain can change the ocean), 2016.

Installation view.

Casting with STPI handmade mulberry paper, 55 x 75 x 85 cm.

Artwork produced at STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery, Singapore]

© Rirkrit Tiravanija/STPI. Installation images of “Exquisite Trust (Blindly Collective Collaborations)”, STPI Gallery, 2017.

Courtesy of STPI. Photo: Katariina Traeskelin

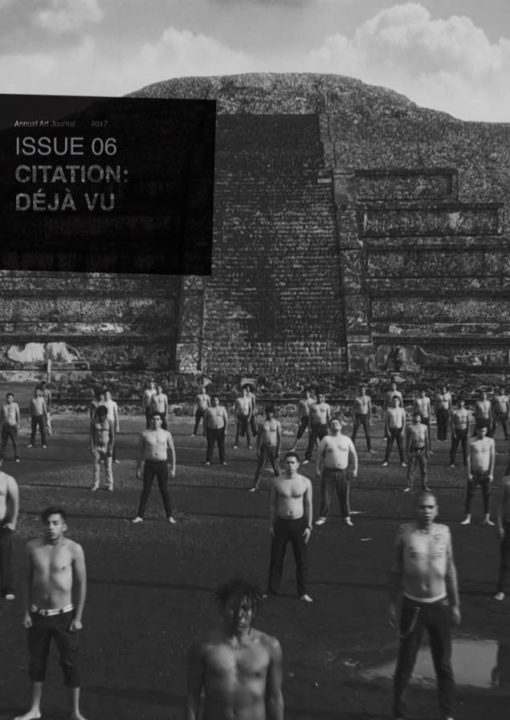

untitled (demain est la question), 2015

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris

Photo: Florian Kleinefenn, 2015.

untitled (all those years at no. 17e london terrace), 2012.

Courtesy of the artist and kurimanzutto, Mexico City

Photo: Estudio Michel Zabé, 2012.

untitled (tilted teahouse with coffeemachine), 2005

Courtesy of the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

Photo: Sillani, 2005.

© Rirkrit Tiravanija