The citing and appropriation of music from other sources by composers and performers has been commonplace for many centuries. The following is an account of the use of quotations from the Classical era, the Jazz era and in American Popular music from the mid- to late 20th century. This essay discusses aural traditions, the appropriation of culture and racial tensions in the transformation of original music into new works. This essay also explores the quotation of Popular music in Classical music and vice versa, the unique practice of musical mockery and the communication of coded messages in music.

The Greatest Form of Flattery

Before the conservatory system emerged in Paris in the 1800s, composers developed their craft by studying and, in some cases, literally copying successful music of the past. The fact that many of Beethoven’s greatest hits can be traced to Mozart—with no intent to hide the origin—would indicate that copying ‘best practices’ was one of the most accepted ways of learning the craft of composition at the time. Another celebrated story about this process concerns a young J.S. Bach reaching into a cupboard late at night to secretly copy a manuscript that his older brother forbade him to use. That Bach learned his craft by copying contemporary hits is further emphasised by his transcriptions of great concertos by his Italian contemporaries, especially those of Vivaldi.

Composers commonly used structures and distinct forms of successful compositions in their own work. As Charles Rosen demonstrated,1 Schubert famously used the finale from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in G, Op. 31, No. 1 as a blueprint for the finale of his own Piano Sonata in A Major, D959. The finale of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor borrows nearly exactly from the finale of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in D minor, K.466. Brahms, in turn, based the finale of his D minor Piano Concerto, Op. 15 on that of Beethoven’s. The finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony became particularly fertile ground for this type of ‘structural quotation’. Robert Schumann (in his Fantasy in C, Op. 17, 1st Movement) and Liszt (in his Piano Sonata in B minor, Op. 53) used the overall structure of the Ninth’s finale as the architectural plan for their own masterpieces.

Like musicians in the pre–conservatorium era in Europe, the learning of Jazz music in America in the early 20th century happened in an experiential way, not in an academic setting. Jazz musicians have often outright rejected the academic approach to learning music. Jazz was formed in the musical polyglot of New Orleans—in brothels and bars in Storyville—and has always retained a romantic connection to the street as its source of authenticity. Lawrence Berk opened Schillinger House in 1945 and dedicated it to the teachings of his mentor, the great polymath Joseph Schillinger, and the Schillinger System of Musical Composition. This later became Berklee College. A systemised approach to teaching Jazz was subsequently formulated in the mid-1960s at Berklee by people like Jerry Coker, David Baker and Jamie Aebersold. The phrases of earlier Jazz musicians were transcribed (for example, the Charlie Parker Omnibook), analysed and appropriated into a system of patterns for the study of Jazz improvisation. Books full of these musical quotations were transformed into Jazz exercises and published as ‘how-to’ approaches to learning Jazz. Many have argued that the dissection of Jazz for academic teaching has been detrimental to the genre. Two decades earlier, in the 1940s in New York, Miles Davis had dropped out of Julliard to play with Charlie Parker on 52nd Street, forsaking the classroom for the musical education of the jam session.

In its purest form, Jazz is studied like an aural tradition. The language of Jazz is passed down from improviser to improviser through live performances and recordings. Novices listen, analyse and imitate their heroes. Modern Jazz musicians quote musical excerpts taken from early Jazz recordings and incorporate them into their own playing as a rite of passage. This form of quotation serves as a learning mechanism, provides an aural connection and is a show of respect for masters of the past. The improvisational language of Jazz music and its cultural traditions could be said to be kept alive through this form of quotation where listeners can hear echoes of Louis Armstrong or John Coltrane in the performances of contemporary musicians.

Ownership and the Transcendence of Appropriation

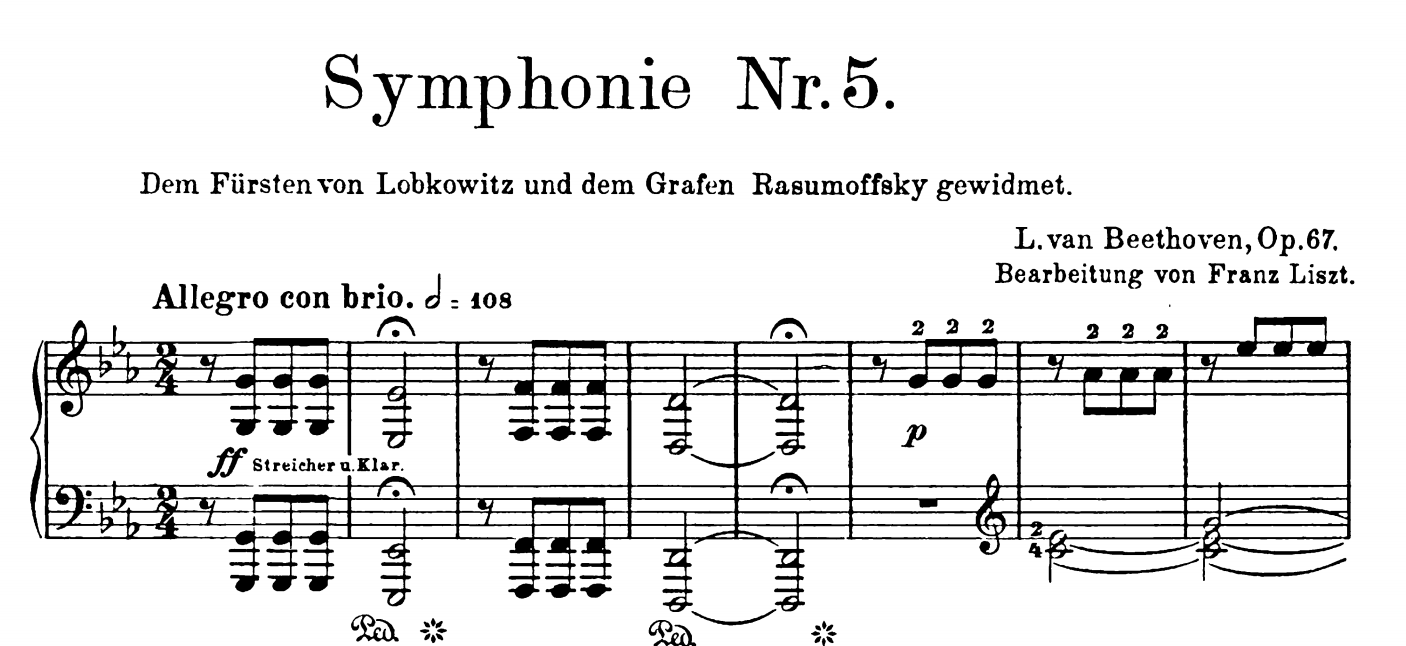

It is one thing to musically appropriate and another to appropriate, then utterly possess the original and transform it into your own image. Beethoven practically made a career out of it. Perhaps the most iconic Classical music motif of all time is the opening four notes to his Fifth Symphony in C minor, Op. 67. Beethoven remade the common rhythmic pattern of this Symphony into a brand identity, and any composer using a similar rhythmic pattern after would be heard to be invoking the great master. Yet the rhythmic pattern, Fate Knocking on the Door, of his Fifth Symphony was utterly common in his time, and often used in accompaniment and melodies. For example, see the opening of Clementi’s Piano Sonata in G minor, Op. 34, No. 2, composed in 1795:

Opening of Clementi’s G minor Sonata, Op. 34, No. 2 (edited by Moscheles)

Opening of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67

(transcribed by Liszt)

Here we have the iconic rhythmic gesture of Beethoven, and the key he made so famous, C minor. A brief glance at the two examples above illustrates a very small step from the Clementi excerpt to the iconic Fifth Symphony opening (and also to the opening of Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata, composed three years after Clementi’s sonata). Clementi was a colleague, friend and eventual business partner of Beethoven, and one about whom Beethoven spoke with great admiration. Yet, today, who remembers Clementi’s Piano Sonata and who does not know the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony?

The history of American folk and Popular music in the forms of Gospel, Blues and Jazz could be seen as a history of appropriation and transcendence of European music by African Americans. By appropriating European musical building blocks and forms, and combining them with the rhythmic complexities and emotional directness of African music, new musical forms that transcended the original materials were created.

The Paris World Exposition in 1889 had a similar effect on European composers. Debussy appropriated the ‘exotic’ sound world of Southeast Asian music, particularly that of the Gamelan he heard at this historical event, which resulted in new ways of musical expression that marked the beginning of the Modern era of tonality and orchestration in Classical music.

Ironically, given the appropriation of European music by African-Americans in the early part of the 20th century America, a continuing injustice felt by African-American musicians was the appropriation of the styles of music that they had developed by Caucasian musicians for their own profit and success. Even though Jazz was undoubtedly created by early African American pioneers like Buddy Bolden, King Oliver and Louis Armstrong, the first ever recording of Jazz was by a Caucasian band (The Original Dixieland Jass Band, 1917). Furthermore, the most highly paid bands in the commercial heyday of Jazz in the 1930s were Caucasian bands like the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, and the orchestras of Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller.

The musicians’ strike of 1942-44 was America’s “longest strike in entertainment history” involving a dispute about royalties being paid to musicians by record companies. During this time no union musician could make a commercial recording.2 What was particularly in dispute was the copyright of melodies. Chord progressions and song forms were less of an issue and this led to musicians recomposing new melodies over the appropriated chord structures of Popular songs. Typically, these songs came from musicals penned by immigrant Jewish songwriters (educated in European conservatories) in New York’s Tin Pan Alley like Jerome Kern, Cole Porter and George Gershwin, among many others.

In the early 1940s, during this creative ‘blackout’, there emerged a new form of cutting edge Jazz called Bebop in the after-hours jam sessions in places like Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem. The practice of appropriating a song’s chords and form and composing new melodies for them became the bedrock upon which the musical style of Bebop was created. By using this method, numerous standard pop songs became ‘owned’ by the Beboppers, and were transformed into a new musical language. The chords and forms for Popular tunes like Honeysuckle Rose became Scrapple from the Apple; Whispering became Groovin’ High, and even Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm was transformed into countless new compositions by Bebop musicians.

At first, the Bebop fraternity was made up of African American musicians who had grown tired of the bland, commercial and formulaic ‘Swing Bands.’ The Beboppers wanted to create a style of music that the Caucasian musicians could not imitate. Bebop was extremely fast and technically demanding. It was more rhythmically complex, and the melodic shapes that they had created over the old song forms were more angular, irregular and unpredictable. The intention of this music was famously unsuitable for dancing and singing. It was a radical backlash of the Caucasian dominated ‘Swing Band’ establishment. The extremes that the Beboppers went to, in forging an original musical style appropriated from European song forms, has been widely recognised by historians and critics as the apogee of African American musical creativity.

Musical Codes and Passwords

An aspect of African music inherent in the later forms of American music was the idea of subliminal coded messages embedded in the music itself. Traditional African drumming used coded messages embedded in their rhythms and the structures of their beating, to send signals to other people in the tribe and even over great distances to neighbouring tribes. Individuals would take turns to solo within these drum groups, further embellishing the code of the idea and adding their own personal comments to the musical discourse. When African slaves arrived in America they were denied their language, customs and music as a way of forcing their assimilation into subservient roles within their new alien society. To communicate with each other, slaves invented sign languages and, in particular, coded ways of singing and making music.

For slaves in the New World, an early form of this coded musical language was the work song performed by chain gangs and later, groups of emancipated African-American workers. For instance “…the all black ‘gandy dancer’ crews used songs and chants as tools to help accomplish specific tasks and to send coded messages to each other so as not to be understood by the foreman and others.”3

One of the first and greatest Jazz stars of the 1920s and 30s, Duke Ellington, said: “people send messages in what they play, calling somebody, or making facts and emotions known. Painting a picture, or having a story to go with what you were going to play, was of vital importance in those days.”4

The famed Jazz saxophonist Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker was the undisputed leader of the Bebop movement and was also its spiritual talisman. To play like Bird, and be accepted into this underground fraternity, many musicians thought you had to live like Bird. This went as far for some as developing a heroin addiction like he had. Musicians in this group who were hooked, and in need of a fix, would whistle the first few bars of one of his tunes titled Parker’s Mood as a musical password, to signify that there were other addicts nearby, and it would be possible to score.

Within Bebop, the idea of being in on a private musical joke or showing solidarity to a rebellious musical movement grew out of the racist exclusion of African Americans from the commercial profits of the music that they had created, and can be linked back to the codified ways of communication embedded in the musical expressions of slaves. It was not surprising that African American Jazz musicians developed the habit of sending musical signals to those who were ‘in the know.’ This included not only musical gestures, but a whole new vocabulary of euphemisms to describe the music and the people who played it. ‘Bad (Arse)’ typically referred to someone who was exceptionally good at performing Jazz. If someone was ‘hip’ they were one of the group, someone in the know, and they were able to ‘get’ the music and understand its hidden language.

Introducing the Everyday into the Sublime

A once vibrant source of musical quotation for Classical composers came from Popular music. Classical musicologists tend to designate Popular tunes that survived as folk music, making it more ‘acceptable’ to use for the loftier aims of great composers. All of the greats quoted from the Popular music of their day.

For example, the Bach family made a musical game of quoting Popular music and creating spontaneous canons and fugues from them. This was apparently their version of light party entertainment. Beethoven is said to have used two Popular tunes of his day for the second movement of his Sonata No. 31 in Ab, Op. 110. The two tunes translate into My cat has just had kittens and I’m a slob, you’re a slob. They follow the music of the first movement, one of the loftiest and most sublime musical utterances ever.

As far back as the 16th century Popular tunes infiltrated the great polyphonic music of the Catholic mass—the ‘parody’ or ‘imitation’ masses would use as source material Popular songs of the day. An equivalent today might be a mass composed from melodies, bass lines, rhythms and harmonies from a Popular musician, a veritable ‘Missa Gaga.’ Perhaps the outcomes of Vatican II in the 1960s to transform the Latin mass into English, including the composition of folk inspired Popular hymn styles, could be seen as an historical throwback to these earlier times.

When it comes to the use of Popular musical quotes in Classical music, there seems to be a special place reserved for the use of children’s tunes. One of Mozart’s most beloved variation sets is based on Ah vous dirai-je, maman or what we may more commonly know as Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Chopin quotes one of his homeland’s most beloved Christmas carols, a lullaby for the baby Jesus, Lulajże Jezuniu, in the B section theme of his Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, Op. 20. Mahler uses the tune, Frère Jacques, for the finale of his Symphony No. 1, cleverly using the minor mode to hint at sinister undertones to this happy melody. Debussy quotes two of his favourite children’s tunes multiple times, Nous n’irons plus a bois and Do, do, l’enfant do.

In America, the Beboppers and the Jazz musicians who followed would insert quotations of Popular songs into their solos to refer to “experiences that artists associated with the titles or the key lyrics of songs…Roy Haynes [Jazz drummer] fondly recalls an occasion when Charlie Parker improvised a ‘burning’ [intensely creative] solo in which he quoted The Last Time I Saw Paris repeatedly ‘in different keys.’ Unable to contain his curiosity afterwards, Haynes asked Parker what actually had happened ‘the last time’ Parker saw Paris[!]5

“Sometimes, [in a Jazz performance] the titles of compositions serve as instructional codes, as when soloists quote tunes like I Got Rhythm or I Didn’t Know What Time It Was when the rhythm section begins to lose its coordination, destabilising the beat.”6 Not unlike some of the coded purposes of earlier work songs to achieve synergy between groups of workers on a chain gang, if a drummer was playing out of time or the bass player started slowing down, a soloist (other member of the band) might quote these well-known tunes to send a musical message to his fellow players to listen out, catch up, and get back together musically with the rest of the group.

Everything Old is New Again

Everything Old is New Again, a song by the late singer-songwriter/recording artist, Peter Allen, touches upon a very human issue concerning a longing for days gone by or ‘the good old days’, when love seemed easier, people appeared nicer, values were much better, life much simpler and there was a tenuous but lingering illusion of hope for a better future:

Don’t throw the past away

You might need it some rainy day

Dreams can come true again

When everything old is new again

Generation after generation of musicians, songwriters and performers continue to bear out this Peter Allen theme of ‘everything old is new again’ when ‘dreams can come true again’, through the appropriation of identifiable musical motifs from ‘the good old days.’ Direct and indirect quotation, identifiable variations of themes, digital sampling and often the wholesale hijacking of compositions are common practice in the creation and production of Popular Music, especially if the original source music is in the ‘public domain.’

Two classic examples of the wholesale appropriation of Classical compositions in Popular music can be found in Elvis Presley’s 1960 #1 hit, It’s Now or Never, and the 1965 #2 U.S. pop hit record, A Lover’s Concerto, by the African American girl group, The Toys. Based on the music of Italian composer, Eduardo di Capua, O Solo Mio transformed into It’s Now or Never with the help of English lyrics written by Aaron Schroeder and Wally Gold. A similar accomplishment was achieved by the two, now legendary American songwriters of A Lover’s Concerto, Sandy Linzer and Denny Randell, who drew their hit song from Minuet in G Major by Christian Petzold (a composition previously credited to J.S. Bach), found in Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach (1725), which is a compilation of the works of a variety of composers of the late 17th and early 18th centuries. However, the two songwriters changed the original 3/4 time meter to 4/4, which is the basic pulse of Rock & Roll and Popular dance music in general. They also made minor adjustments to the original melody in order to accommodate the flow of their added lyric. The record sold more than two million copies, and has benefitted from numerous cover versions and motion picture features—quite an accomplishment for music written more than one hundred years prior.

Two iconic examples of appropriating portions of musical content from Classical compositions are the product of pop singer-songwriter/recording artist, Eric Carmen. Having attended the famous Cleveland Institute of Music as a child, Carmen gained an obvious affection for the music of Russian composer, Sergei Rachmaninoff, basing two of his most famous pop hits, Never Gonna Fall In Love Again and All By Myself, on the adagio from Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2, and the second movement (Adagio sostenuto) of his Piano Concerto No. 2 in C minor, respectively (being from a family of Russian immigrants, I wonder if there is a more deep-rooted connection to the music of Rachmaninoff that inspired Carmen to appropriate his music and apply it so effectively). Unfortunately, Carmen was under the mistaken impression that both Rachmaninoff compositions were in the public domain and, not surprisingly in today’s litigious climate, was approached by the Rachmaninoff estate informing Carmen otherwise. An agreement was reached, whereby the Rachmaninoff estate would receive 12 per cent of the royalty income of both songs).

An even more extreme and odd example of this quest for ‘things past,’ the pops, scratches, hiss and generally degraded sonic ambience of old vinyl recordings, that digital technology was to magically eradicate with the advent of the compact disc, are now being introduced back into Popular recordings through software plugins specifically designed and developed to emulate those previously unwanted sounds that were once considered dreaded distractions. Record producers are adding those previously cursed sounds back into their pristine digital recordings to give them a ‘retro’ or ‘dirty’ sound. ‘Dirty’ is in, and ‘clean’ is out, which largely took root among the African American musicians and producers in the early days of Rap, Hip Hop, and House Music beginning in the 1980s, not for the reasons stated above but, because the lo-tech instruments available to them at the time were cheap. Expensive analogue instruments, previously out of reach to most people, were literally being thrown out in favour of the new false messiah of digital instruments, and now, those trashed instruments are demanding a premium far above their original selling price, if they can be found. Even in this way, “everything old is new again” has taken root in the obsessive production of ‘analogue-modelled’ software synthesisers.

Musical Mockery and Situational Jokes

There are several instances where the use of a musical quotation to mock someone exceeded the fame of the original composition. Two iconic examples of great compositions that resulted from musical competitions involved Mozart in one instance and Beethoven in the other.

On Christmas eve in 1781, Mozart was summoned by the Emperor Joseph II. Instead of being asked to play, however, Mozart found himself being introduced to Muzio Clementi and soon in competition with him. At the behest of the Emperor, Clementi duelled Mozart, at least to a draw, to Mozart’s everlasting, bitter chagrin. Nearly 10 years later, Mozart composed one of his operatic masterpieces, The Magic Flute. In the overture, Mozart composed a three-voice fugue, using one of the most effervescent themes he ever wrote.

But that fugue subject was lifted nearly note for note from the opening of one of the compositions Clementi performed during their duel so many years before, the Clementi Sonata in Bb Major, Op. 24, No. 1.

Given Mozart’s lifelong animosity towards Clementi, and the bitterness he must have felt over having met a rival he couldn’t easily defeat, it is credible that Mozart used Clementi’s theme in part to show him up. Clementi obviously took the joke personally, for in every subsequent publishing of his sonata during his long life, he made sure to always mention that his sonata was composed long before Mozart’s Magic Flute.

One of Beethoven’s greatest hits also resulted from an improvisation contest. Daniel Steibelt, a German-born composer and pianist who was Beethoven’s contemporary, challenged him to a musical duel. The story goes that Steibelt went first, leafed through a recent composition, then dramatically tossed it aside before beginning his improvisation.

When it was Beethoven’s turn, he reportedly picked up the composition Steibelt had tossed aside, turned the last page upside down, then began to improvise on the theme that emerged from the final eight measures. As Beethoven’s improvisation became ever more impressive, Steibelt realised he was being made the brunt of a joke and left, supposedly never to return.

Years later, Beethoven used the musical quote from Steibelt’s composition for his Piano Variations Op. 35 and the finale to his Symphony No. 3 in Eb, the ‘Eroica’, Op. 55. Given Beethoven’s often-confrontational [JC15] relationship with his contemporaries, it is believable that he used the theme from his crushing victory to remind all competitors who was the king.

There are many examples of Jazz musicians using musical quotations in reaction to the environment they might be performing in, providing a situational joke for the benefit of the aficionado’s presence—whether they be other band members or audience members—if they were ‘hip’ enough. Again Charlie Parker was one of the most ingenious proponents of this technique:

…. he could see something happening and play upon it on his instrument. Like, he’d see a pretty girl walk into the club we were playing. He’d be playing a solo and all of a sudden he would go into A pretty girl is like a melody where ever he was [in the form of the song we were playing] and make it fit in. Or someone was acting a little crazy and he would play something to fit that.7

Parker famously quoted the opening bassoon melody of The Rite of Spring at the moment he saw Igor Stravinsky sit down in the club he was playing. Apparently Stravinsky nearly tipped his drink over and everyone roared with laughter at the musical quotation of his famous work. One of the best examples of Parker playing a musical quote that has yet to be decoded was his spontaneous use of the sea shanty The Horn Pipe over the bridge of probably one of the most demanding and stylistically archetypical works of the Bebop era, Ko Ko (created over the song form of Cherokee) recorded in 1945. The quotation is in plain sight, but todate no one has deciphered the meaning of the quote and why he played this seemingly innocuous ditty in the middle of, arguably, one of his most well known masterpieces.

In the early 21st century, technology enabled musicians to sample or ‘lift’ music from any piece of music that has ever been recorded. In the past few decades, the advent of Hip Hop and RnB heavily sampled music from other genres and movements like ‘plunderphonics’ that only used samples of other people’s music to create post-modern musical collages of sourced materials meshed together. Before we had the technological capacity to cut and paste music instantly from one format to another, composers indulged in musical duels and mocked each other by copying a rival’s work and then making it sound better and more commercially successful. Early African American Bebop musicians used the standardised forms of pop songs from musical theatre shows to create a whole new form of Jazz and continue the traditions of coded messages embedded in African drumming and Pop composers in America were appropriating excerpts from the European Classical music tradition to create top-selling hit songs.