Souvenirs from the Past that Never Was1

As a phenomenon that implicates memory and perception, warping our sense of space and time in the process, déjà vu – no matter how many times we have experienced it – leaves us puzzled every time. Imagine being in a certain place, taking in the setting and the objects within it, on one hand certain that we have been there previously but, on the other, our instincts signal that we are experiencing this scene for the first time: “I have been in this room before; the table of books with the lamp and the vase are so familiar to me… yet I cannot place when exactly I saw them last.” Our perception insists that there is something that we are trying to recall here, yet our memory tells us that there is nothing in the past that corresponds to what we are seeing in the present. It is this disconnection between perception and memory felt in déja vu that evokes a sense of strangeness and, within that fleeting moment, it is not uncommon that we begin questioning the accuracy of what we perceive and what (we think) we remember.

For the Italian philosopher Paul Virno, the experience of déjà vu, as described above, points to one of its distinct characteristics regarding the nature of the past it implicates. Compare déjà vu, for instance, with remembering the birth date of a loved one: while that date may be recalled with confidence, the time that we try to recollect in déjà vu is ultimately less certain. Thus for Virno, déjà vu is concerned not with the recollection of a “dateable, defined” past that unquestionably occurred in a specific location at a given point in time, but rather a sort of “past in general” that may not have happened at all.2 Characteristic of déjà vu, unlike the memory of past birthday celebrations that is anchored to a specific moment that has gone by, is that it conjures a kind of non-chronological past, a past without a definite position in time. As such, déjà vu is a unique mode of experiencing time.

Another characteristic of déjà vu, as observed by different writers from an Oxford English Dictionary entry of the term,3 points to the sense of familiarity that the experience evokes: the definition of déjà vu states it to be “the correct impression that something has been previously experienced; tedious familiarity…”4 In his book on déjà vu, Peter Krapp notes that such a characteristic of déjà vu is also present in Walter Benjamin’s interpretation on kitsch, a subject that began to be a point of academic reflection by the early 20th century against the backdrop of rampant mass industrialisation and the increasing commodification of art. For Benjamin, the appeal of kitsch – typically mass-produced knick-knacks that decorate the corners of the domestic home – lies in its familiarity. Kitsch objects produce the effect that “this same room and place and this moment and location of the sun must have occurred once before in one’s life,”5 and this sensation matters more than whether or not that past moment had actually occurred. In Benjamin’s account, kitsch makes apparent the familiarity that characterises déjà vu.

In this essay, building from the temporal characteristics of déjà vu as identified by Virno as well as the link between déjà vu, familiarity and kitsch drawn by Benjamin, I wish to extend the discussion by focusing solely on the kitsch objects of souvenirs. While souvenirs typically function as a marker of memory – an “I♠NY” t-shirt as a keepsake from a trip to New York City, for example – I draw attention instead to souvenirs of unvisited places – for instance, a Merlion fridge magnet that may have been bought in Batam without one having been to Singapore at all. While souvenir studies typically focus on its role in embodying the memory of firsthand, lived experiences, I try instead to position the souvenir in terms of the experience of déjà vu as theorised by Virno and Benjamin. To do this, I will refer to an exhibition I co-curated for Singapore Art Week 2016, entitled Fantasy Islands, paying particular attention to its exploration on the issues that surround souvenirs.

I propose that the familiarity evoked by the souvenir is symptomatic of a particular process of staging a national narrative: it is by facilitating an imagination about a place that souvenirs familiarise it. Here, I extend Susan Stewart’s theorisation on the ‘longing’ that souvenirs implicate, by asserting that the souvenirs discussed in this essay present a particular longing for familiarity within the necessarily alienating and foreign dynamics of global tourism. However, in contrast to Stewart’s perspective that longing is a pathological state linked to nostalgia, I see longing as a productive force in its capacity to reveal what Virno refers to as a “potential now.” I conclude by offering the view that souvenirs from places that were never visited make the distinction between nostalgia and déjà vu evident. This essay proposes a way of interpreting souvenirs beyond its usual preoccupation with nostalgia by analysing it according to the framework of déjà vu, thereby emphasising dimensions of the souvenir that are not necessarily tied to the memory of the places that the souvenirs are meant to represent.

“A Past in General” and the “Potential Now”

Discussion about the strangeness of déja vu often revolves around Freud’s theorisation of the phenomenon.6 Like the phenomena of chance encounters and the double, Freud’s déja vu brings us into the realm of the uncanny, where the familiar and the unfamiliar lose their distinction and are seen to be symptomatic of a pathological “compulsion to repeat,” aimed at fulfilling repressed desires. Yet a theoretical framework that pathologises déja vu may not, in fact, prove helpful for the purpose of teasing out what déja vu reveals about concepts that are related to our understanding of time. For instance, it neglects questions regarding the nature of a past that is conjured by déja vu, what it reveals about our constructs of memory, and how this influences our conceptions of history.

For Benjamin, such an experiencing of time – seemingly problematic due to its inherent obscurity – nonetheless plays an important role in the way we understand the workings of history. His interpretation of déjà vu explains to us the relationship between past, present and future that is operative there. In déjà vu, we are transported “unexpectedly” to the past, and while the sensation “affects us like an echo,” “the shock with which a moment enters our consciousness as if already lived through tends to strike us in the form of a sound” occurs simultaneously.7 While this may remind us of Proust’s description of involuntary memory, Peter Szondi and Peter Krapp argue that unlike Proust, whose search for lost time propels him deeper and deeper into the past, Benjamin seeks a connection between the past and the future: whereas Proust preserves the past as impenetrable and inaccessible, Benjamin sees the past as something that unfolds into the future.8 Even though the memory that emerges from déjà vu may be false, it is nonetheless important to consider what kind of future that such a reliving of the past opens toward: “if I have been in this situation, I might know what will happen next; there might be a clue left for me of what is yet to come.”9

This line of argument that gives a specific position to déjà vu in the historical experience – which is conventionally centred on the dynamics of remembrance and forgetting – is pushed further by Virno. He argues, somewhat controversially, that not only is déjà vu not a mere lapse in either memory or perception, it is in fact the very condition for historical possibility. Here, Virno’s argument goes beyond two dominant understandings of history: firstly, that history is an endless quest to put together pieces of the past in the present in order to preempt a vision of the future and secondly, the Nietzschean tradition that sees an active forgetting as necessary for history, because one needs to learn to forget (i.e. be unburdened by the past) in order to move forward. Both, according to Virno, rests on the assumption that any knowledge of the past serves to affirm the now that we are living through. This leads to a danger in the way history is understood, which Virno refers to as “modernariat”, where the endless fragments of the past are gathered solely to affirm and validate what happens in the now.10

According to Virno, what déjà vu reveals is the dual-dimensionality of the now: the “actual now” and the “potential now,” that are being remembered as it is being perceived. As Hiyashi Fujita notes, this conception of déjà vu as both memory and perception is already theorised by Henri Bergson, for whom “the cause of déjà vu is perceiving a certain scene at the same time as recollecting the memory that is currently being perceived.”11 In déjà vu, memory and perception – which in any other experience would remain distinct from one another – becomes entwined; we can no longer maintain that perception is a property of the present moment and memory as that of the past. This two-fold nature of the now that is exposed in déjà vu opens an alternative version of how history may be construed: “learning to experience the memory of the present means to attain the possibility of a fully historical experience.”12

The past conjured by déjà vu may seem false and illusory – and thus easily overlooked – but Virno’s study is instructive in terms of situating its position within a larger consideration of the historical experience.13 Drawing from Bergson, Virno explains that déjà vu summons not a “dateable, defined,” particular past, but a “past in general”, highlighting that, in déjà vu, what matters “is not this or that former present” but rather “a past that has no date and can have none.”14 As déja vu evokes, in the present, a “past that was never actual”, it thus underscores a “potential now” that must not be overlooked in the experience of history.

A Longing for Familiarity

For Susan Stewart, longing is a manifestation of nostalgia, a phenomenon that brings an idealised past into the present and makes it seem more real. In her book, Stewart explains that physically, different forms of longing come to be manifested in the objects of the “miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir and the collection,” and that it is the souvenir, in particular, that signifies the “longing of the place of origin” where the “authentic” – whether experience or object – is encountered.15 As a narrative-generating device, the souvenir creates myths of authenticity: this is no more apparent in an increasingly mediated world where the body no longer becomes the primary mode of perception, and where claims for authenticity are inevitably linked to the articulation of “fictive domains” such as the “antique, the pastoral, the exotic.”16

Focusing solely on the function of the souvenir in embodying the memory of past experiences, for Stewart, the souvenir serves to “authenticate the experience of the viewer.”17 The souvenir, as neither an object of “need or use value,” speaks through a “language of longing” to represent events that are deemed “reportable.”18 Interestingly, Stewart continues to explain the “incompleteness” of the souvenir: first, by being an object that represents an event or experience (e.g. a Big Ben pencil case as a souvenir from a visit to London), and second, it must remain incomplete to allow the supplementation of a “narrative discourse.”19 Specifically, the souvenir generates a narrative of the originary place of the authentic experience, thus simultaneously signifying a nostalgic longing to return to that place and authenticate the memory of having been to that place in the past.

In Stewart’s theory, ‘longing’ is symptomatic of the “social disease of nostalgia,”20 where the present experience of the souvenir is marked by an impossible desire to return to the time where the place symbolised by the souvenir was visited; putting it differently, the “actual now” is characterised by the futile yearning for a “dateable, defined” past. However, in the case of déjà vu, such a past, as the above discussion on Virno’s theory explains, is non-existent: we have never been to that place previously. While Stewart is certainly helpful in explaining the sense of longing that the souvenir embodies, could this longing be felt even in the absence of such firsthand experiences, in the case of souvenirs of places that were never visited? In Virno’s terms, such souvenirs uncover a “potential now” that refer to a “past that was never actual,” in other words: to déjà vu rather than to memory. The question that then needs to be posed is: how does longing operate in déjà vu, in the absence of a past place that may be relived in its memory? If the souvenir is tied to the time of déjà vu rather than memory, then what kind of longing does it manifest – what does it long for?

Early 20th century theorists of mass culture define kitsch against the backdrop of rampant industrialisation and the resulting rise of a mass culture of consumption. A “genuine culture” that takes time to fully mature is replaced by an artificial culture that, belonging to an elite few, developed rapidly and whose reach encompasses the many. Kitsch – quick to produce and reproduce, formulaic, and imitative – embodied this new artificial culture that is perceived as “a debased form of high culture.” Benjamin’s theorisation of kitsch, similar to other thinkers from the period, is shaped by such an intellectual backdrop and is unique in its mention of kitsch’s familiar appeal. On one hand, kitsch objects embody modernity in being mass-produced. On the other hand, rather than being treated as a modern shock of the new, kitsch is similar to folk art in being known, prosaic and mundane: the lure of kitsch is “like the feeling of wrapping oneself into an old coat.”21 Krapp notes further that for Benjamin, kitsch is able to return us to this familiar space-time – regardless of whether such a space-time ever existed at all – because déjà vu does not simply entail a “rational repetition and recognition, but rather a different experience of space-time.”22 In other words, the warped space-time that déjà vu generates allows us to hark back to a space-time of familiarity, in spite of its illusory, non-actual nature.

In the absence of an “authentic,” “lived,” firsthand experience of a place – as in the case of déjà vu – the souvenir then cannot be seen to stand for a longing to return to that place. Yet despite such absence, déjà vu retains a sense of familiarity, and it is a longing towards it that the souvenir thus points to. If, as in the instance that Stewart puts it, the souvenir is tied to the memory of a place once visited, then the resulting longing is driven towards a recoil to the past place. However, given that the souvenir is linked instead to déjà vu, the souvenir signifies a longing for familiarity instead. In déjà vu, the souvenir does not embody a search for a past that has happened; instead, it signifies the search for the sense of familiarity so much so that it does not matter if the past really happened or not.

Souvenirs from the Past that Never Was

For Singapore Art Week 2016, I was involved in a curatorial project entitled Fantasy Islands that sought to explore the relations between Batam and Singapore. Among other trajectories, an area that was examined in the project was tourism and how it facilitates the construction of “island-fantasies.” The title of the exhibition itself drew from the name of the resort Funtasy Island, located on the northwestern tip of Batam, advertised to be “the largest eco park in the world.” Managed by a Singapore-based developer, the resort stood largely incomplete at the time of exhibition, and a Singaporean newspaper during that time reported a possible dispute between Singaporean and Indonesian authorities over ownership of Pulau Manis, the island where the resort is located.23

\

\

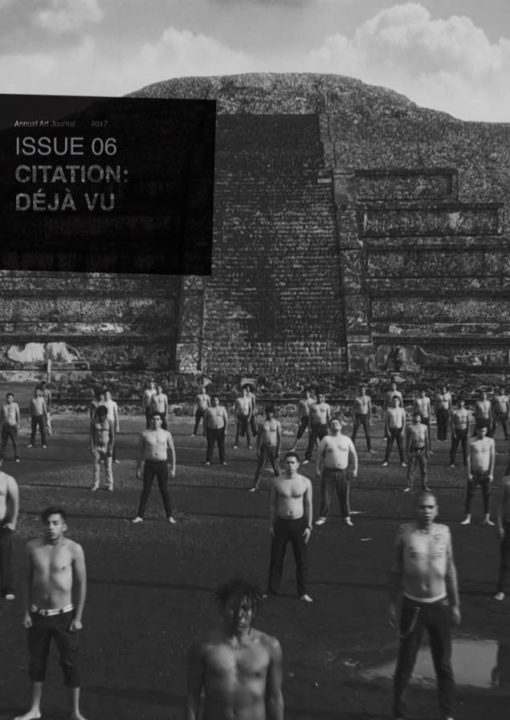

Figure 1. The Funtasy Island marketing booth at HarbourFront Centre.

Courtesy of the author.

The photograph (fig. 1) was taken at Singapore’s HarbourFront Centre, a shopping mall that doubles as a ferry terminal and connects Singapore to nearby Indonesian ports, including the island-city of Batam. Looking at this photograph, the “island” appears staged by property developers to appeal to potential buyers and tourists. It conjures an image of the possibility of being a global citizen that divides him/herself between two different islands in two different countries. During the course of the project, I reflected upon the tourist experience as it is shaped by particular types of places: the borders that exist between the two islands, the ferry terminals or ports at both Singapore and Batam, and shopping malls as places of consumption visited by tourists.

During my research, I observed groups of tourists who, benefiting from the high-accessibility of ferries between Batam to Singapore, extended the cosmopolitan narrative of cross-cultural engagement in the form of shopping (here, phrases like “shopping-holidays” come to mind). One of my earlier visits was to Batam’s Nagoya Hill, the island’s largest shopping mall, and one could easily make out from the variety of shops and goods on offer at Nagoya Hill that it is catered for lower-middle class consumers, as we can see from the image of a shop called “Orchard Shoppes Avenue” (fig.2). It is a part-fashion, part-souvenir shop, yet it was harder to find souvenirs from Batam than souvenirs from anywhere else in the world. Although t-shirts, bags, and baseball caps with Singapore logos and slogans are placed where people would easily find them, souvenirs from Batam were actually buried under and hidden away. I speculated that part of the reason for this may be that, to many Indonesian migrant workers at Batam (the majority of whom are not passport-holders), it is seen as more prestigious and sophisticated to give souvenirs of Singapore to friends and family back home, even though they have never set foot in Singapore.

Figure 2. Orchard Shoppes Avenue, a souvenir shop in Batam’s Nagoya Hill.

Image courtesy of Eldwin Pradipta.

This leads us to question the nature of souvenirs in our time of tourism. As part of the exhibition (fig. 3) display, we included souvenirs bought from the two islands, even if they did not represent Batam or Singapore directly. Among these were miniatures of Eiffel Tower, Dutch windmills, Malaysia’s Petronas Tower. They were considered important parts of the exhibition as they allowed us to question the relationship between souvenirs and memory. If souvenirs function primarily as markers of memory – conventionally, they serve to remind us of the places we bought them from – then what sort of experience are we trying to get by buying souvenirs of places from which we have never been?

Figure 3. Fantasy Islands, exhibition view of souvenirs.

Image courtesy of Fantasy Islands team.

To put it differently, if what we are trying to experience is not the Eiffel Tower, the Dutch windmills, Petronas Tower, and so on, as they were “lived” – since we never had firsthand encounters with them – then what role do these souvenirs play in ascribing value to the places that they are supposed to represent? Here, a form of déjà vu – an experience of the “past that was never actual” – is evoked by souvenirs that are bought without one having been to the place that the souvenir symbolises. It appears that what we are trying to recollect is not, in Virno’s terms, a “dateable, defined past” that was obtained from firsthand experiences, but rather a past that never, in fact, took place.

The firsthand, direct involvement with a place that is missing from this experience opens up an imagined realm of longing: that place maintains its distance, remaining far and unattainable, and we begin to long for a kind of acquaintanceship despite the fact that we were never there. It is this lack of embodied presence that is substituted by the souvenir, and, as such, the souvenir functions as a familiarising tool, rather than a tool for remembering: the place that one never visited ceases to be so foreign as we acquaint ourselves with the way it is symbolised by the souvenir. Here, the souvenir does not provide an affirmation of a supposedly authentic experience; rather, it serves to momentarily sever the distance that exists between the two places. For instance, France may be an alien territory, but a tea towel bearing images of baguettes and Eiffel Towers make it seem familiar and accessible.

At the risk of hasty generalisation, a distinction may be drawn between the figure of the explorer and the tourist. In her study on souvenirs, Beverly Gordon refers to the 19th century ethnographer Arnold van Geppen, who states that: “A man at home, in his tribe, lives in the secular realm; he moves into the realm of the sacred when he goes on a journey and finds himself a foreigner in a camp of strangers.”24 Unlike van Geppen’s explorer who leaps into the unknown and holds the act of travel as a kind of sacred pilgrimage due to the sense of discovery and authenticity it promises, the tourist moves within the commoditised circuit of package holidays and pre-booked tours that spectacularise the “authentic” experience. For the tourist, what is desired is not necessarily proof of firsthand experience – “I have seen with my own eyes the grandeur of the Eiffel Tower and the couple kissing underneath it” – but an affirmation of the place which the souvenir testifies to, whose identity has been idealised through the complex maze of marketing, advertising and branding strategies. As such, the souvenir not only validates the branded identity of the site but also familiarises it, rendering it if not intimate, then certainly recognisable. It tames the site so that it no longer appears inaccessible. It matters less that one has never visited Paris, Singapore or Batam, and more that the souvenir symbolically reduces the distance – real and imaginary – that remains between places.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the beginning of this essay, déjà vu bewilders us as it stands at the intersection between memory and perception; it is the momentary disconnect between what we perceive and what we remember that envelope déjà vu with a distinct sense of strangeness. Freud’s account of the phenomenon positions it, under the “uncanny,” as a pathological symptom to be remedied; while the influence of Freud’s framework is no doubt far-reaching, it remains limited in addressing, for instance, the temporal dimension of déjà vu as well as the role of physical objects in shaping the way déjà vu is experienced.

An alternative framework for analysing déjà vu is offered here by referring to the characteristics of déjà vu as identified by Benjamin and Virno. Here, Benjamin is instructive for two reasons: first, for putting forth an interpretation of déjà vu that is not confined to memory and the idea of an inaccessible past, and suggesting, instead, that déjà vu is part of the historical experience where the past unfolds to the future; and second, for linking déjà vu to kitsch by emphasising the felt dimension of familiarity. The temporality of déjà vu is elaborated further by Virno, who asserts that déjà vu reveals a “past that was never actual”—a dateless, non-chronological past that is experienced in an alternative version of the present moment, which he refers to as the “potential now.” Regarding kitsch objects and the déjà vu experience, this essay focuses solely on souvenirs from places that one has never been to, refers to Stewart’s idea of longing, and suggests that the “potential now” opens up a dimension of longing for familiarity – rather than a longing for what Stewart calls the “authentic” experience of places that were visited in the past – within the alienating setting of global tourism.

The focus on souvenirs from unvisited places is drawn from the curatorial project entitled Fantasy Islands, in which I was involved as a co-curator. Though the project was specifically centred on the relations between Batam and Singapore, it nonetheless opened an opportunity to consider the contemporary role of souvenirs. Observations made during the project showed that souvenirs do not necessarily represent the memory of firsthand experiences of a particular place. While nostalgia may be a defining trait of souvenirs that are attached to a person’s firsthand experience and the wish to recollect that experience from memory, souvenirs of places that were never visited evoke instead a déjà vu in its quest for familiarity. Nostalgia is driven by the desire to reclaim memories of the past; such reclamation is prohibited from déjà vu, and souvenirs of unvisited sites may be seen as its material manifestation. Additionally, it must be noted that, rather than representing an impossible longing to return to past places, such an approach to souvenirs presents instead a desire to domesticise and demystify foreign lands that are beyond one’s reach – a desire that is no doubt shaped by concerns such as social accessibility, which is a pertinent issue that lies outside of the scope of this essay.