The following article was published in Calendars (2020-2096) for the exhibition of the same title of Heman Chong’s work, in 2011 at NUS Museum, Singapore.

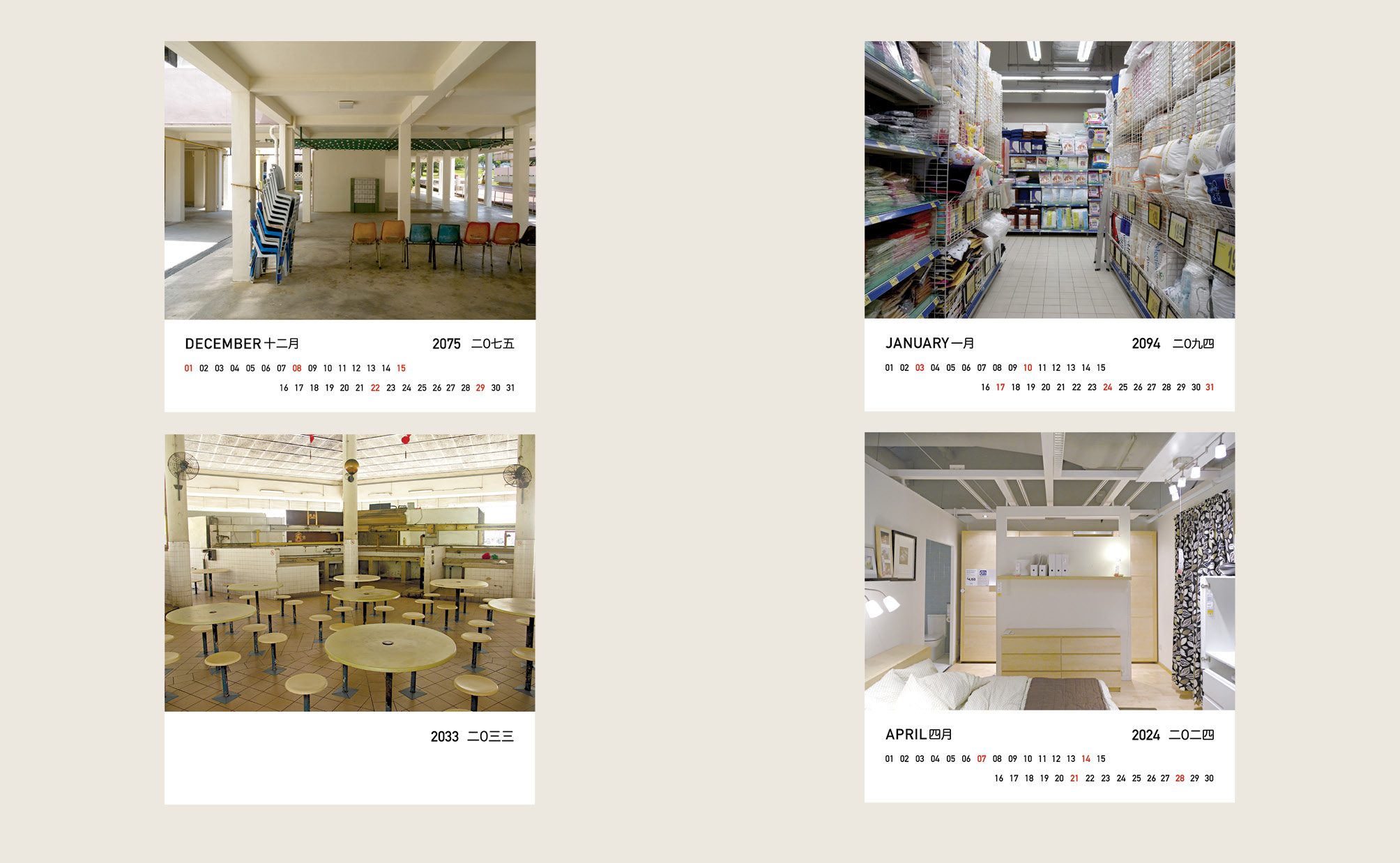

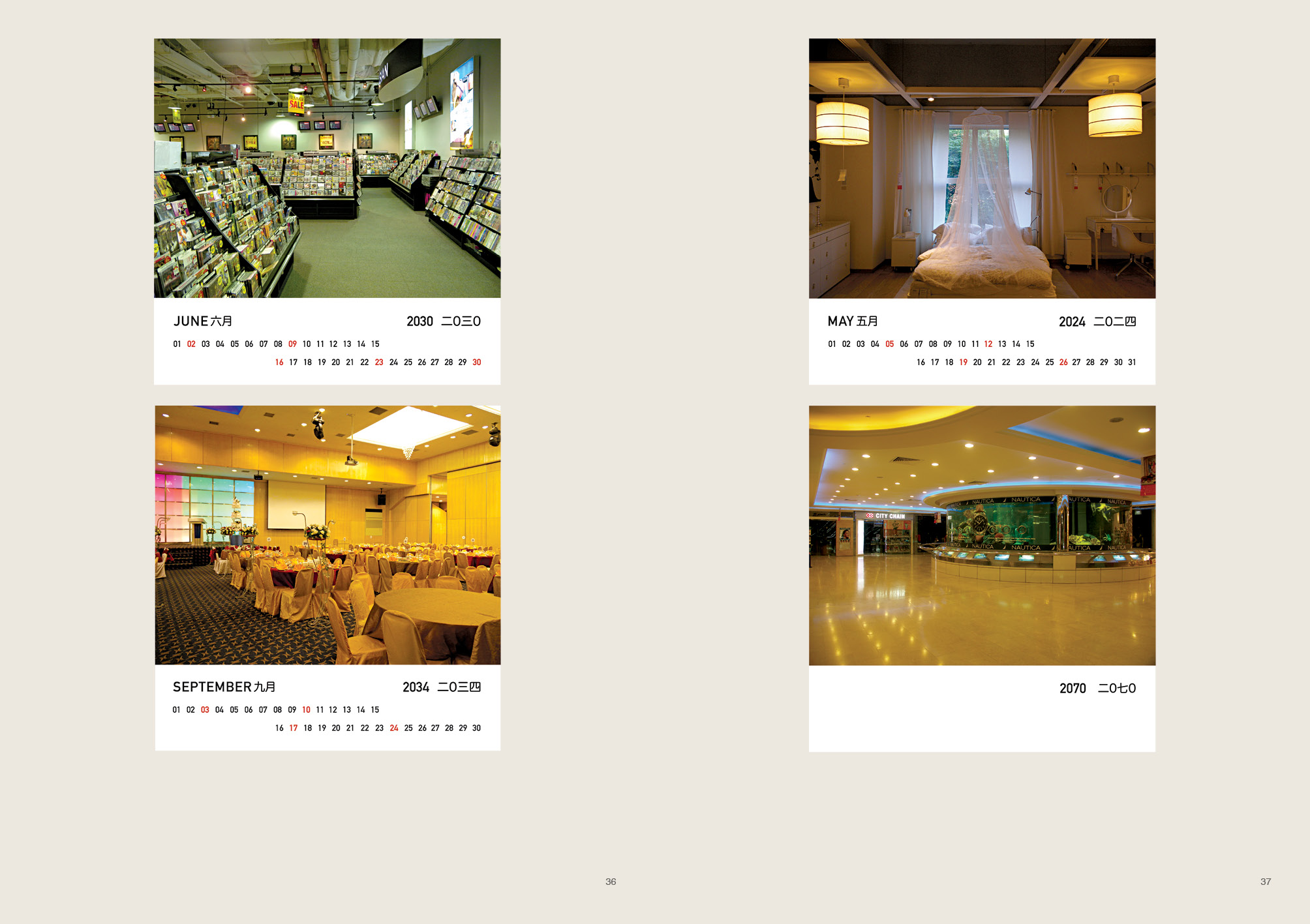

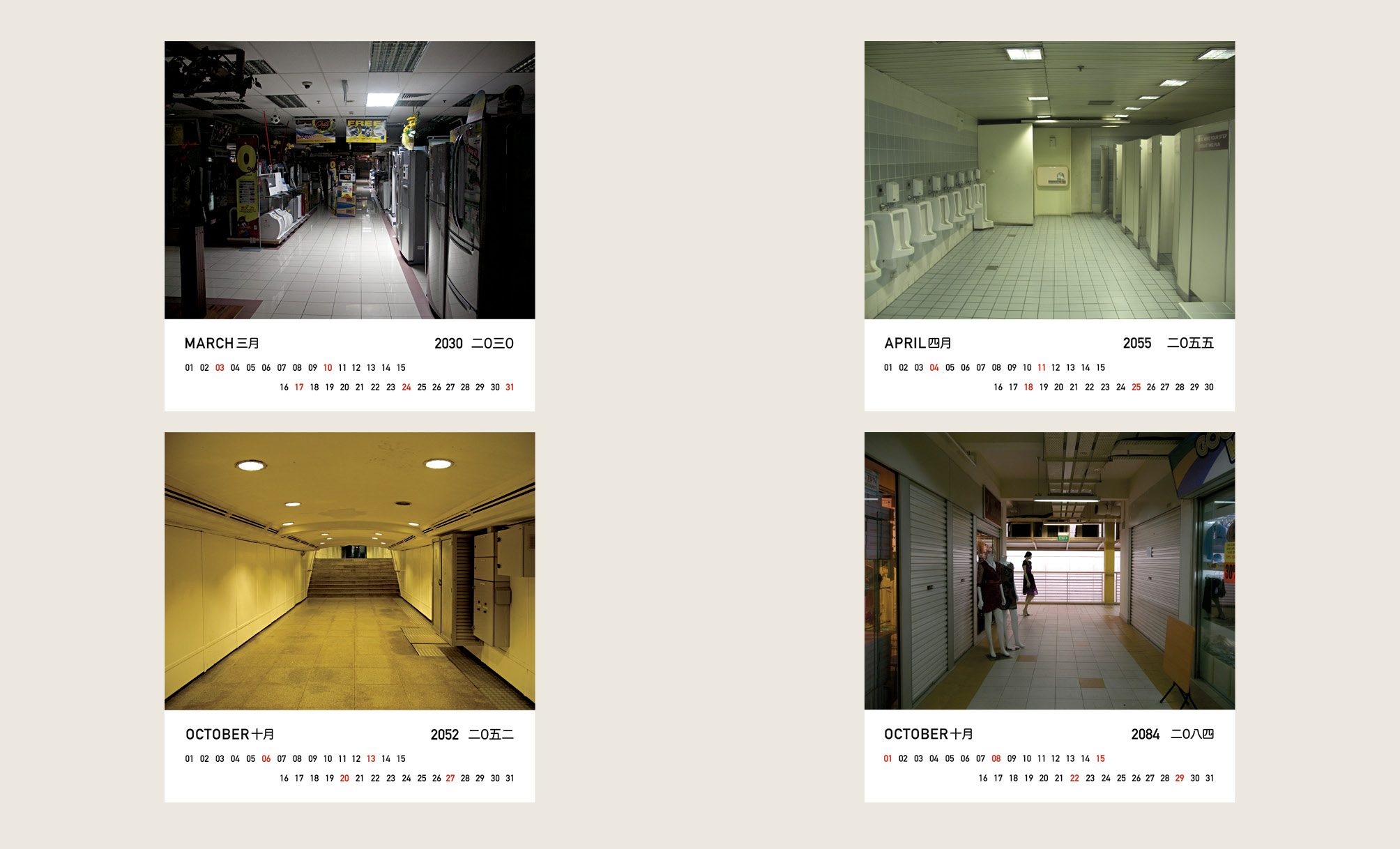

Heman Chong’s installation at the NUS Museum consists of 1,001 photographs presented as 2020 to 2096 calendars. Collated over a period of seven years, the production of these images was guided by a set of simple rules: these photographs are taken during periods of public access, and that they are emptied of people. Photographed in various parts of Singapore, places visited by the artist included public housing estates, shopping malls, eateries, tourist sites, and an airport; these emptied spaces were conceived as tableaux, within which subjectivities may be deployed or e nacted by their viewers, complicated by a conceptual interplay with the calendar as a notion of linear time. Chong describes the work, installed in a gridded format occupying an entire gallery, as a “dream machine”, an intriguing apparatus without an operations manual characterised by its servitude to the impulse of imaginings rather than objectively determined: “How can this construction be useful to anybody except myself?” Heman Chong discusses Calendars (2020-2096) with Ahmad Mashadi in relation to his expansive practice as artist and a curator, and authorial strategies that involve collaborations, appropriations and quoting, and synoptical devices that facilitate modes or reception.

Mashadi

You work with multiple projects moving quickly from one to the next; Calendars (2020-2096) consist of vast set of images, completed over a lengthy period. You described the project’s immensity by its references to “time, space, situation”. Conceptually one imagines the project sustains a particular approach of practice. Where do we start?

Chong

We can start by talking about the value of coherence in an artistic practice that is situated in the context of today; how can we measure the value of an artist’s contribution to the language of art, and in turn, to the landscape of cultural and knowledge production? Viewing the situation from my perspective as a relatively young artist from Singapore who has more or less discarded a trajectory of production that revolves around the usual suspects of specific mediums like installation, painting, sculpture as grounding points (which is something that is prevailing, not only in Asia, but across the other continents as well), I am much more interested in working with these methods as conceptual vehicles for a basis of discussion about issues and things surrounding us. For example, I am interested in how a series of painted images; images of book covers could, very quickly become, an auto-biographic tool which then very quickly shifts into a series of hysterical recommendations to people of which books they should read. So, in a way, it’s somehow about surpassing the need to focus on one’s ego, to extend a dialogue beyond the idea of the self into something much larger.

Mashadi

That is interesting. It is that very question of coherence in which many had commented on a sense of ambivalence on your part. We can go into the specifics at a later stage of the discussion. For now, let’s push on with some generalities. Where the demands of contemporary production involve multiple negotiations, the coherence being referred here disavows any formal categories and instead, as you pointed out, revolves around manners of working and attitudes. In other words, you develop conceptual strategies and it is within these conceptual strategies that we may locate productive perspectives of an artistic practice, an autobiography as you put it. There are so many things to unpack here. Let me start by asking you if you can expand the phrase you beautifully used “…to extend a dialogue beyond the idea of the self into something much larger”. It seems to me it demands another way of thinking about the “authorial” and “authorial strategy”, not effacement of self, but rather affording into the practice forms of slippages arising from contexts, peoples, and encounters…

Chong

I feel very strongly that our identities are constructed around the things we associate ourselves with. And I am also conscious of the fact that I exist in a very privileged situation where I have an abundance of associations to work with. The questions that often haunts me are: What will I do with all this material? Is there a way to use it so that it reflects both a private world and the world at large? How can this construction be useful to anybody except myself? Do I want my work to be useful at all? One strategy that I have imagined over the years is to perform a set of recommendations, namely of novels, to the ‘audiences’. This, of course, extends directly from the conceptual legacy of ‘pointing at things’. I feel happy when people email me to talk about a certain novel they have just read because of a painting that I made, or a mention of that novel in an interview, and how we can come together not to talk about me or my work, but to discuss certain interpretations of that novel. For me, it’s important to have such a basis for any kind of conversation, a plateau, where we are teaching each other something, learning from one another.

Mashadi

I guess you are referring to ‘identities’ in the potentials as something indeterminate, something situational perhaps. The projects of where you work alongside others carry risks. Based on what you have just said, the writing project Philip (2006) is an interesting one… you brought a group of people together—artists, designers, curators—to initiate a ‘science fiction writing workshop’ eventuating with a publication. Here the term collaboration is structured with pre-assigned roles and process, and the outcome—the book—identified. The otherwise singular voice of the author is replaced with a sequence of different voices, each simultaneously pushing and pulling as one struggles to sustain one’s intertwined status as an individual and as part of a collective. Here, in many ways ‘process is form’, and that at times necessitate one to embrace the potentials of failure (at times we fetish over it). To what extent, as a project initiator, do you surrender to risks?

Chong

I guess the thing about empathy is that when we start to feel for someone, when we begin to bridge ourselves to another, we start to change. And there is a great desire inside me to want to change. Not so much as a moralistic exercise (for the better) or having a day out (for the worse), but something that falls in-between the two (for better and for the worse). No, I don’t really want to consider risk as part of the equation, because I’ll be too afraid to do anything that might foster change. Within the context of Philip, we soaked ourselves in this atmosphere of being impulsive, of writing whatever we wanted that immediately became part of a larger imagining. It was super interesting to how the entire ecology within the novel was literally constructed out of the multiple viewpoints that each of the participants brought with them, and how their cultural and emotional baggage contributed to the minute details that became the architecture of the world. At the same time, it became very clear, very early on in the project that two of the participants in the writing workshop, Steve Rushton and Francis McKee, both had this amazing ability to be able to juxtapose and edit the worlds into a singularity. There was a lot of trust involved in that situation, where we knew that our input into the novel would be weaved together in a way that could become something… readable.

Mashadi

Does it prompt a newer regard in your thinking about the public? You earlier remarked on the importance of public reception to the works. How easy was it to engage a readership where the integrity of art in its final form should be negotiated to solicit the potentials of collective production, a fluid plot that is contingent on accumulative and sequential contributions from each participant?

Chong

We discovered that there is an audience that craves to encounter a process as such. And that finally, it was this process that drew them into reading the novel. It has also to do with the distribution of the novel. Initially, we printed a hundred copies as a first edition, to raise funds to cover the production costs of the project (which worked) and then we had the second ‘run’ parked within Lulu, a print-on-demand service. We also distributed the novel freely as PDF, without any charge. Who wouldn’t want a free copy of a science fiction novel?

Mashadi

Joint authorships like Philip is one aspect of your practice. Ends (Compiled) (2008) takes on a different approach, It affords you to take on a ‘collaborative’ strategy that is appropriative rather than one that involves negotiations. You chose passages from published books written by various authors. Here we can return to your thoughts on a practice having an autobiographical inference, in a sense that passages in Ends, actually may suggest ways predicaments interact with ironies or suspended resolutions sketched out by these respective authors. You chose from Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker (1937) “… striving to win for their race some increase of lucidity before the ultimate darkness…”. It is about the idea that entity is part of a collective organism, and knowledge is relational to one another, finality unattainable…

Chong

On some days, I sometimes feel that I am eternally damned to just merely being someone who can quote very well, and never seen as a artist who can actually produce something original. It is, perhaps, my greatest anxiety in my life. Even if appropriation has very clearly been validated by both institution and individuals as a completely legitimate way of producing meaning, I guess, personally, I’ve always wished that I never used it. Somehow, it’s something that’s way too flippant. Too easy… Even though Ends (Compiled) was in fact, an extremely well choreographed work, both in the selection of texts and the way it has been presented as a sculpture, I remain dissatisfied. At the same time, it remains to be a very useful tool especially when I’m asked to ‘interact’ with a certain preconceived idea from a curator about a certain situation or a space… what I’m trying to say is that appropriation is great when you need to develop something like a ‘non-denial, denial’ or a ‘non-event, event’.

Mashadi

By the phrase ‘non-denial, denial’, you are referring to attempts in developing formal and conceptual tensions that resists curatorial or institutional affirmations?

Chong

It is not so much an act of resistance as much as a reminder that, like it or not, we live in complex times and as a result, frameworks drawn of out of easy categorisations can fail in an extremely uninteresting way. Just take for example, how contemporary ‘Southeast Asian’ is being defined: most curators would gladly take on tribalism and animism over conceptualism and intellectualism…

Mashadi

We had discussed the question of the ‘authorial’ as an artistic predicament, but in many ways it is within your curatorial practice that the question seems most urgent… Difficult to tell if it is an extension of art practice. We worked together several times in particular for We (2008) and Curating Lab (2009) where you referred to the collation of materials we gathered for the exhibition and the artworks as ‘collecting’. It seems to me this is a way to remind ourselves that they have agency while at the same time ‘possessed’ in the manner in which the quotations you just referred to have resonance in saying things that may (or may not) be defined to one’s positions.

Chong

The two roles are interchangeable and I have never sought to define them in strict terms. Just as I have never really played the ‘Asian artist’ card in an explicit manner (especially when invited to shows in Europe and North America), even if a lot of my work deals with a lot with the various trajectories in which intellectualism and conceptualism has failed to take root in Southeast Asia. I don’t have a desire to take up mantles that would allow for easy compartmentalisation. I have observed, in the past ten years of being an artist and playing such a loosely defined role, it has this effect of distancing myself from curators and gallerists who find my work ‘too confusing and too difficult’, but at the same time, I have also encountered a group of curators and gallerists who are completely into this definition. For example, I know for a fact, that the Singapore Art Museum is one institution that has dismissed my work as being ‘too international’ for their taste.

Mashadi

Yes, identities forced along notions of ethnicity and nation can be quite a burden, which good or bad, are forms of currency in art-making and reception, here as much as elsewhere. I think it is not a question of resistance, but rather perhaps insisting for a critical engagement that acknowledges the contingency of multiple contexts and references. Your focuses on technology, society and fiction, and your methodical, almost hyper-rationalised use of texts and graphics are calculated to insist this is a difficult proposition?

Chong

I refer to a work that I made in 2009 entitled The Forer Effect, an appropriation of a text within an experiment by Bertram R. Forer that has the same nickname. He issued a personality test to his students and told them that they would each be receiving a unique personality analysis that was based on the test results. They were to rate their analysis on a scale of 0 (very poor) to 5 (excellent) on how well it applied to themselves. In reality, each received the same analysis:

‘You have a great need for other people to like and admire you. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved. Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.’

On average, the rating was 4.26. Only after the ratings were submitted, Forer revealed that each student had received identical copies composed by him from various horoscopes of the day.

In light of this, what I’m trying to say is that while words don’t come easy to most people when they are trying to define a situation, to some, they come a little too easy.

Mashadi

Let’s discuss this obliquely in relation to the current Calendar project which was conceived sometime back, before you left Singapore for New York. You had undertaken a number of photographic book projects focusing on Singapore sites before initiating the Series. What were they? What did you aim to achieve in these book projects?

Chong

I never have had a master-plan for anything in my life. Mostly, I just improvise and adapt along the way. The reason why I mention this is because, when you look at Calendars (2020-2096), you will get the impression that from the very beginning of the project, I knew what I want to do. Which is completely not the case at all. When I began to photograph these interior spaces accessible to all (most) people, I did it because I was searching for a new idea, a new beginning, a new way to collect images. I believe very strongly in the power of observation, where you will literally just look at something, break it down in your head in the most logical way possible and then ‘archive’ that sensation of that image. I don’t have a photographic memory, and that is why I rely on photography for that part of the process. These spaces, they intrigue me, on a structural level and also on an emotional level. Somehow, I know that they are so susceptible to change, to every sway of policy, to every new wave of capital… In a way, it was the same with the books I made, about specific sites in Singapore. The first was about Telok Blangah Hill Park, where the National Parks Board commissioned this totally insane structure which runs from the foot of the hill to the top, something we came to know of as ‘Forest Walk’. I am inherently interested in how ideas affect spaces, and how spaces can be representative of certain things that we (or more aptly, ‘they’) would be concerned with, at a certain point of time. In this case, somebody really had this idea of a nature reserve that is accessible to ALL, including the least attractive people of society, the handicapped—people without any means of mobility. They built a huge metal structure, which functions as a giant meandering ramp up (and down) this hill. I find this completely fascinating, how they even could start of conceive of such an idea. How does a conception about a GIANT RAMP UP A HILL start?

Mashadi

From the perspective of production, the project is unburdened by any assumptions on outcomes. I understand that it is largely conceived along the need to generate fresh trajectories of practice, but the notion of cities suddenly emptied of its inhabitants is rich in its potential, not least in science fiction. You spent time in places like shopping centres during opening hours waiting just for the right moment to capture a scene without anyone present. Is there a conceptual underpinning here defined by ideas connected to plausible settings in science fiction? Or is there a commentary element—dystopia of sorts?

Chong

I would say that Calendars (2020-2096) locates itself within a conceptual framework of utilising gestures, in this case, that of waiting and appropriating images within a specific moment, that moment of absolute emptiness, which can be quite rare considering how densely populated Singapore is. But at the same time, it has this dimension where I am also interested in formulating a kind of fictional landscape, one which reflects all the concerns of dystopic narratives, especially of the ‘last man on earth’ genre. This genre often deals with a global cataclysm which results in the near annihilation of the human race. Whether it’s an ecological disaster or a full-blown biochemical infection, the stories usually become humanitarian; they are stories of how humans can survive the worst possible situations.

So in a way, I am interested in staging the landscape in which these stories occur, and to use them as banal images for a banal activity, that of recording time…

Mashadi

Based on your earlier remarks, the Telok Blangah project seems to conceptually point towards the ironies and contradictions of spatial production… and in some ways in same manner in which we regard science fiction as having its furtive roots of criticality with the contemporary, the Telok Blangah and Calendar projects seek a placement into the current day.

Chong

But also to suggest that our imaginations are also important in placing ourselves into the everyday, that we have possibilities to imagine ourselves inside and outside of situations. For me, this is one of the crucial skills of a good artist.

Mashadi

The decision to present those images as calendar illustrations was made during the period of photography?

Chong

Yes. I took seven years to complete the entire project, and a huge part of it was to allow for a series of divergences to occur without any kind of prior planning involved. So a lot of it was left to chance, and one of the results, for example, was to use the photographs as accompanying objects to the actual marking of time.

Mashadi

How many images are there in total? How are these images organised according to the years, and are there particular ways in which the images are being clustered? At some point you decided that the large body of images were best mobilised as an exhibition. You mentioned earlier about the forms of subjectivities and your wish to facilitate through these images. How do you intend to display them? It seems that placing the images and into a calendar format allows you to intimate towards some of the conceptual interests you were talking about. The subject of post-apocalyptic (or even post-rapture) world may directly be inferred. The calendar, the suggestion of an impending event, gives a millenarist tinge to the work? And the condition of present as another.

Chong

There are 1,001 images in all. I arranged the photos according to a series of categories, which are evident in the spaces themselves—corridors, shop fronts, big rooms, small rooms, etc. There are also some categorised by sites—Depot Road, Haw Par Villa, IKEA, etc.

There’s a lot of contestation with the actual presentation, and I think it might be best at this point to follow a certain grid within the space, and to show all 1,001 pages containing all seventy-seven years of calendars within a single plane. I chose the year 2020 to start the calendars as a result of an observation about the idea of 2020 as the year in which all the problems in the world could possibly be ‘solved’. In many political press releases, we can notice this kind of promise, and of course, we now understand that these projections do not necessarily mean that any of the promises can or will be fulfilled. We constantly have to manage this sense of disappointment when it comes to such statements from the people that we thought we could place our trust in.

Mashadi

In that respect the images can also be taken in relation to specific potentials, beyond a universalising notion of time markers resplendent in economic or social programmes. These are specific locations whose economic, social and even political utilities are shaped by prevailing structures and responses to the same. Does that put you in an uncomfortable position as observer/commentator, offering a critique on the politics that informed the production of such spaces and their dystopic inevitabilities?

Chong

I don’t see it as an uncomfortable position at all. I think art is a language in itself, and has its own potentials. I don’t want to apologise for speaking this language, but at the same time, I acknowledge that this language can only be understood by a very limited community, often causing a lot of misunderstandings when art projects are discussed within other fields like sociology or politics. In recent years, a lot of artists have been working in this field of producing knowledge, and while I appreciate a lot of the material generated from these projects, it is something that I don’t want to do, at least not in the way of producing knowledge like how an academic would. I prefer to work along the lines of subjectivity and speculation, and mostly, I just let things go wild, let them become hysterical. In my work, I don’t want to place the emphasis on ‘making sense’.

Mashadi

Yet there are formal elements that insist we look at them as enquiries of spatial organisation, order, placement, tonal value etc. In that sense there is a generousity that imbibes the viewer’s place. These images cam be ‘free floating’ too, their significations negotiated by the viewer themselves. Their post-apocalyptic reference inflected by conditions of spectatorship…

Chong

It is about constructing a kind of dream machine, a space which allows for dreaming of all sorts… How these spaces, dislocated as photographs immediately become empty stages which all kinds of things can occur.

Mashadi

To end, can we go back to the question of the ‘authorial’, how an artist’s relationship with his viewer is a complicated one? The ‘synoptical’—the invocation of an expansive and general view of things—affords multiplicity of perspectives and readings. To what extent do you regard its limits? I am thinking about One Hundred Years of Solitude, the work that you presented for the Singapore Biennale in 2008. It conflates many things… the original book by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the billboard as a capitalistic expression of imposed desire, and predicaments as currency of negotiation…

Chong

A project that has been on my mind for a long time is to write to all the political ministries around the world that regulate advertising in public spaces, and to propose that they would reserve a certain amount of advertising space for the promotion of novels. While there is no certain quantifiable data that reading novels (at least the ones that are worth reading) makes for a better society, we can all at least agree on the fact that we would have less of half-naked models with unreal bodies in skimpy white underwear to confront.