In this article, I will describe a project which is still in progress: a translated video archive of radical re-elaborations of Javanese wayang kulit puppetry. Although this project is very specific in terms of its content, its philosophy and methodologies might be akin to those of projects in other fields and artistic disciplines. Therefore, although I will describe the specificities of this project, my objective is to examine its more general implications.

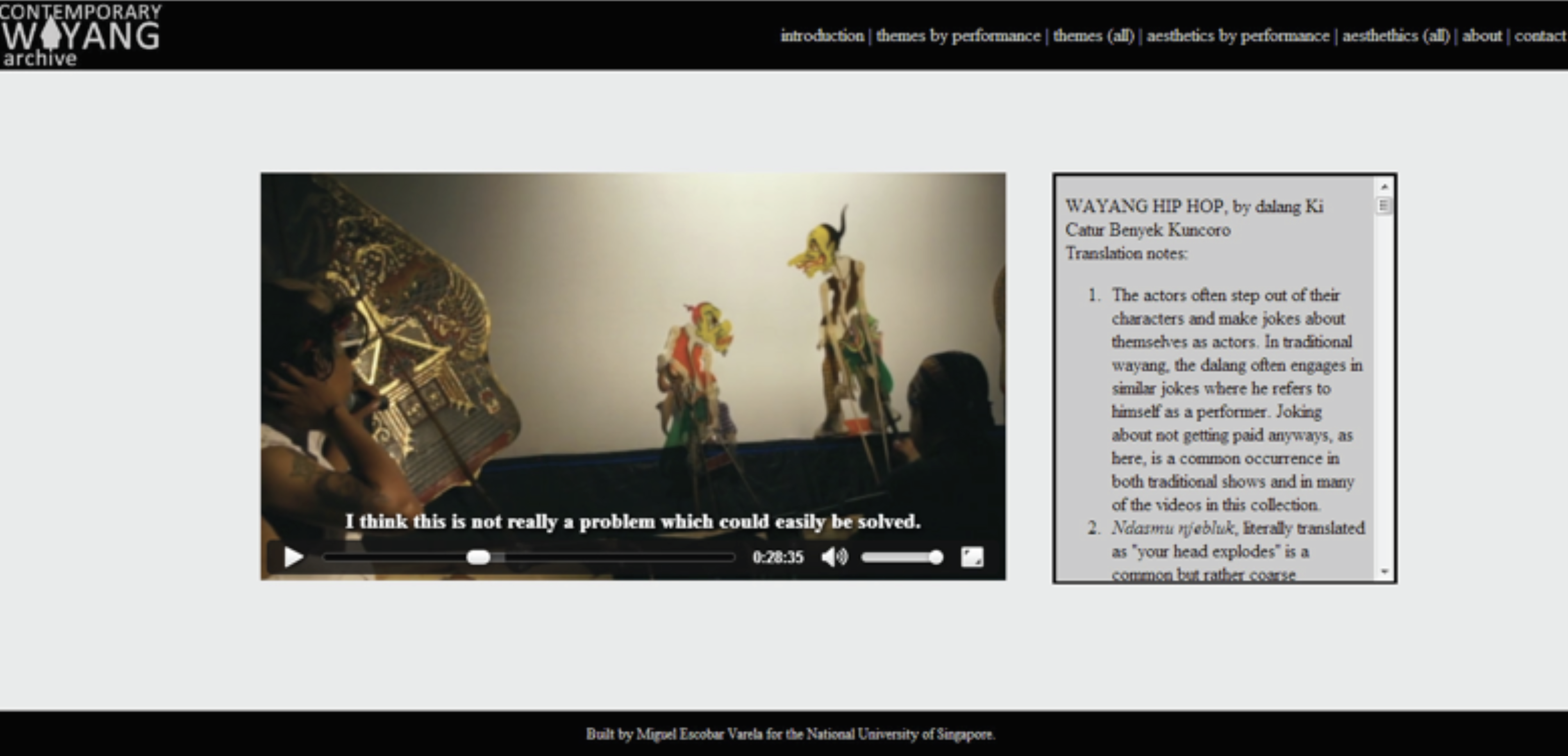

Translation on the website is not limited to a direct rendering of the words used in the performances in another language. Rather, it encompasses contextual explanations specific to each performance, general introductory notes and glossaries. All of these elements, taken together, add an explanatory layer to the videos. This layer was designed to provide the visitors of the website with an interactive set of options, allowing them to navigate through the subtitled videos—pausing and rewinding them at will—while reading through the notes and consulting the explanations. Since all of these materials are interrelated and serve the same purpose, I propose to call them the ‘Digital Mediation Ecology’ of this online archive. Mediation here means that these materials have an intermediary role, allowing for visitors that are not familiar with the cultural and linguistic universe of wayang to learn about the complexities of this art form and about the rich web of references that springs from the performances.

1 A screenshot of the development version of the online archive.

I believe that this understanding of translation places this project after a long line of anthropological and humanist projects that aim at offering an understanding of how art works within different cultures. As Edward Said wrote: “The task of the humanist is not just to occupy a position or place, nor simply to belong somewhere, but rather to be both insider and outsider to the circulating ideas and values that are at issue in our society or someone else’s society” (2004:76). Inspired by this understanding of humanism, this web archive aims to allow for this dual perspective, by opening up an avenue into the understanding of that which is at stake, ethically and aesthetically, in the most radical re-elaborations of Java’s oldest performance tradition.

The Archive

The Contemporary Wayang Archive (CWA) includes two dozen video recordings of new versions of Javanese wayang kulit called wayang kontemporer [contemporary wayang]. All of these performances were recorded in the past decade. Five of them were recorded especially for the archive, while the rest were part of the personal collection of the dalang (puppet-masters). Combining tradition and new influences, these performances are more accessible than the traditional ones and they represent, thematically and formally, key trends in sociocultural change patterns in Indonesia.

In order to appreciate the significance of these new versions, there are several features of traditional performances which one must consider. Although traditional performances are still common and held in high respect, young people living in cities consider them too inaccessible for three reasons. First, they are too long. A traditional performance lasts seven to eight hours. Not surprisingly, barely anyone witnesses the entire show, which begins at 9pm and ends at around 4am. The first scene, called adegan jejeran, conventionally consists of an audience scene in front of a king. This scene can last up to two hours and most of the dialogue consists of formulaic exchanges between the king and the emissaries who wish to address him. This formulaic talk is a necessary precursor to the discussion of the main problem or perkara. In other words, during most of this scene there will be no direct mention of the main dramatic problem of the performance. The perkara will only be discussed toward the end of this scene, which might well be one hour and a half into the performance. This usage of time sits in stark opposition to the fast-paced narratives to which many people are becoming used to through mass media.

Secondly, the performances are linguistically complicated. A traditional performance is delivered in Javanese, a highly registered language. In a Javanese conversation, speakers must chose the correct register or level in which to address an interlocutor, which can be ngoko, madya or krama. Each of these levels has its own vocabulary set and there is very little overlap among them. This high degree of semantic variation is so diverse that one could almost think of the levels as constituting independent languages. Young people living in cities are increasingly less interested in mastering all these levels, and the most polite one, krama, is falling in disuse. Besides these conventional levels, a wayang performance also makes use of kawi, an old version of Javanese which is closely linked to Sanskrit and which few people understand nowadays.

Thirdly, the performances are too far removed from the everyday life of young spectators. The stories are based on the spiritual quests of the heroes of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, the Javanese adaptation of the eponymous epics of Indian origin.

However, new versions of wayang bend these traditional rules. The performances in the archive last between forty-five minutes and three hours, and they often use exclusively the lowest register of Javanese (ngoko) or they are delivered in Indonesian instead, the official language which is rapidly replacing the vernacular languages in the performing arts. The stories are also adapted to be closer to the world of spectators. They can be adaptations of old stories or new stories all together. Sandtiama Lagu Laga (2012), by Nanang Hape, is an example in case. This combination of theatre and wayang explicitly compares the biography of two wayang characters, Gatotkaca and Karna, with the lives of young people living in Jakarta.

Another example is Pertaruhan Drupadi by Slamet Gundono. This performance narrates the episode of the Mahabharata where Puntadwa loses his wife Drupadi on a bet. Eventually, he will gain her back, but in the meantime she faces the threat of rape by the Kurawa—the sworn enemies of Puntadewa and his brothers. Infuriated, she sets on a trip around the world, seeking justice, and meets then-president of the United States George Bush. This scene is a good example of how the comic genius of Slamet Gundono brings together the Mahabharata story and contemporary affairs.

DALANG. So George Bush was taking a shower. He came out of the White House, looking arrogant and vain because he had just attacked Iraq and won the war against Saddam Hussein. Apparently his favorite music was not dance, disco or jazz… but Bendrong from Banyumas.

BUSH. Who is looking for me?

DRUPADI. I am the one looking for you.

BUSH. Who are you? I am busy.

DRUPADI. Are you truly George Bush?

BUSH. Yes. The President of America.

DRUPADI. I ask for your help, the Kurawa want to rape me.

BUSH. And you are asking for my help? Alright. What do I get in return?

DRUPADI. I ask for help and you immediately talk about payment. Is this really a president? I don’t have anything.

BUSH. Then it’s impossible. There must be something given in return. Something that will benefit my country. We accept oil, we would really like some oil, even if it’s cooking oil.

DRUPADI. This can’t be true, I am asking for help! You are supposed to look after the safety of the world. You should be able to help anyone. I was neglected by my husband who put me in danger.

BUSH. Oh, that’s a menial problem. I am only interested in big events, such as the presidential election in Indonesia. […] Your problem is insignificant.

Similar instances of comic—and more serious—adaptations of the stories to the contemporary world populate the performances in the archive. Aesthetically, these performances are a mixture of traditional conventions and new media. Some of them use other music, such as Hip Hop, Rock and Jazz instead of the conventional gamelan musical accompaniment. Another dimension of aesthetic experimentation refers to the puppets and the materials from which they are made. The word kulit means leather, which refers to the material conventionally used for making the puppets. But in kontemporer versions, leather is often replaced by other materials, such as old bicycle parts, plastic, condoms, dried grass and cooking utensils.

By shortening the duration of the performances, adapting the stories to the contemporary world and introducing new media, the dalang have found a way to maintain the relevance of the wayang tradition. These performances matter because they show how tradition is being adapted to current times. As such, they offer a kaleidoscopic view of sociocultural change in contemporary Java.

Challenges

The objective of the translation on the website is not only to offer a version of the Javanese and Indonesian utterances in English, but to explore the subtleties and richness of the allusions, jokes, and parodies contained in the wayang kontemporer performances. Wayang is highly allusive and the jokes depend on the interpretive competence of the spectators. This project aims to generate a sense of this competence through subtitles, notes and explanations. Wayang is also highly symbolic and relies on very stable, strict and easily recognisable conventions. The transgressions and modifications of these conventions are only meaningful when one understands how they differ from normative expectations.

The translation notes in the website will not only clarify aspects of the language which are difficult to translate into English; they will also explain the usage of music, stories and movement conventions. It aims to allow for an understanding of why these choices are meaningful—or offensive or critical—in their original context. Explaining the complex network of allusions and re-elaborations of aesthetic conventions in kontemporer performances poses different challenges, linked to wayang-specific performance conventions, language games and topical allusions. In what follows, I will explore different examples of all of this.

Conventions

As an example of the conventions used, we can consider the kayon, a large puppet that has very important symbolic and dramatic functions. Shaped like a leaf, this symbol-laden object represents the world in its entirety. In the front, there is a house guarded by two giants armed with club-like weapons called gadha; they represent the dangers in the world. Half-hidden by the building, a pool located beneath the house represents life. The face of kala makara, which represents time, is placed over the house and flanked by a buffalo (representing honesty) and a tiger (representing strength). A tree, which symbolises an individual person’s life journey, grows on top of the head of kala.

The kayon is always planted at the centre of the gedebog or banana tree at the beginning of a performance. When the performance begins, the dalang will move it to the side. At the end of each scene, it will be shortly placed in the centre once more. A slight inclination of the kayon indicates the progression of dramatic time: depending on the angle, one can know the pathet of a particular scene. The pathet structure corresponds to subdivision of the performance into three main sections, with specific musical modes. A kayon can also be used to represent transformations of characters from one state to another, and forces of nature, like fires and floods.

The wayang kontemporer performances often respect the conventions of the kayon’s iconography and functions. However, an extra layer of meaning is often added when new versions of the kayon—with specific meanings—are made for the performances. An example is Catur Kuncoro’s Wayang Republik, a performance that retells the story of the participation of the city of Yogyakarta in the Indonesian struggle for Independence against the Dutch in 1943-45. Although the kayon in this performance has the same shape as a traditional one, its symbolic tapestry has been adapted to represent the city of Yogya. It is believed that the spiritual power of the city depends on the fact that the kraton or Sultan’s palace is located in the centre of a line between the sea and the volcano. The palace, the ocean and the volcano are all represented in the kayon. This puppet fulfills the same dramatic function as the traditional ones. But its subtle re-elaboration of the symbols of the kayon add to the semiotic complexity of the performance. It is not discussed in the play by the dalang, but the notes explain its symbolism. As such, this explanation is part of the translation efforts of the website.

References to Topical Events

Many of the performances refer to topical political figures and events, which also require contextual explanations. As an example, I will discuss Enthus Susmono’s version of the story Dewa Ruci. A conventional wayang show always includes a scene called gara-gara where the punokawan or clown servants come on stage and make jokes that relate the world of the story being presented to the world of the spectators. In this particular performance, Enthus references specific politicians in Indonesia by name, and imitates the voice of the late ex-president Gus Dur. These linguistic and metalinguistic references are also explained by the contextual notes.

2 A conventional kayon used in a performance

(four kayon can be identified in the image).

3 The kayon especially made for Wayang Republik.

Sometimes the references to topical events are not made through words and voices, but through the shape of the characters used. For example, in Wayang Kampung Sebelah, some ‘guest’ performers are introduced. One of them is Minul Dara Tinggi. From her appearance, people now that this puppet represents Inul Daratista, a famous dangdut singer whose provocative, sexy performances and scanty clothes caused a great controversy in Indonesia at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Linguistic Playfulness

Even though the linguistic conventions of kontemporer performances are simpler than those of traditional performances, they still rely on a complex usage of the language. An understanding of the linguistic jokes is crucial to the enjoyment of a performance. As an example, we can consider Wayang Kancil, a performance that uses folk tales protagonised by animals to explore pressing environmental concerns. In one of the episodes of the performance, the main character is a crocodile, which is introduced by the dalang in the following way:

DALANG. It is said that once, on the banks of the Bengawan river, there was a creature, called Crocodile. He was a crocodile, and not a playboy. [1]

4 A puppet representing Inul Daratista.

The number in brackets refers to one of the translation notes. The translation in English tries to maintain the meaning of original utterance, but the play on the sounds is lost. In Javanese, the word bajul [crocodile] is phonetically close to mbajul [a verb that means “to try seduce women, especially ones that one was not previously acquainted with”].

Though similar phonetic jokes abound, there are other ways in which the playfulness of the language is important for understanding the performances in the archive. It has already been explained that the way one addresses an interlocutor in Javanese depends on the relative status of speakers. Even though kontemporer performances privilege the usage of ngoko [low Javanese] and Indonesian, the characters still address each other by choosing one of thirty-two honorifics which demonstrates their relative status. These honorifics range from sinuwung, which is used to address a God, to mas bro, a slang honorific of recent invention used to address friends. A direct English translation would overlook the playfulness and diversity allowed by this choice of honorifics. Therefore, the translation has chosen to preserve the original honorifics in the English subtitles. An information box next to the explanations and translation notes, contains a full list of the honorifics, with explanations and usage examples.

This section has explored the main challenges of translating the wayang kontemporer shows and explained how subtitles, notes and explanations of visual and additive signs were built into the Digital Mediation Ecology of the website.

Specificities

Translation is perhaps as old as language itself. But there are some specificities of using this within a digital environment worth considering. These features are also possible due to the accessibility of the archive, whic will be freely available online.

Correctability: The accessibility also implies that inaccuracies in the translation can be detected by a large community of users and that different versions of the translation can be made available. It is in principle possible to host entirely different translations of the same videos in the same server, allowing viewers to compare the perspectives of different translators.

Modularity: The project can be used as a component of other research projects. A built-in capacity to generate links to specific parts of the videos will be included, making it easy for other researchers or students to share links to specific parts of the videos, easily embedding this in other academic works.

‘Close watching’: The videos can be seen over and over. As the users go back and forth, they can choose from the different array of explanatory material made available, allowing for a different kind of attention to be paid to specific parts of the videos. We can think of a ‘close watching’, as a parallel to close reading.

None of these features are unique to this project and that is where their strength lies. Several similar archives exist and we can expect many more in the near future. It is not a stretch of the imagination to picture that this might become a new research paradigm in the performing arts, where online translated videos supplement more conventional performance analysis. In such a case, Digital Ecologies of Mediation would certainly change the way that academic writing is carried out.