“The time frame of four minutes and thirty-three seconds is purely an artificial parameter, so that period of time we can listen and concentrate to the music of the environment which is constantly ongoing, it never ceases and is continually varied. We never listen to the environment; we’re too busy listening to the thoughts in our head.” –Margaret Leng Tan, Singapore GaGa

For historians, echo provides yet another take on the process of establishing identity by raising the issues of the distinction between the original sound and its resonances and the role of time in the distortions heard. Where does an identity originate? Does the sound issue forth from past to present, or do answering calls echo to the present from the past? If we are not the source of the sound, how can we locate that source? If all we have is the echo, can we ever discern the original? Is there any point in trying, or can we be content with thinking about identity as a series of repeated transformations? –Joan Scott, “Fantasy Echo: History and the Construction of Identity”

Sound Inventory

We take for granted that smell is a powerful trigger of memory, yet what we often forget is that in an ever-changing urban space like Singapore, smell is elusive and impossible to record. Demolishing old buildings, old spaces, and natural spaces means that these smells are gone for good—to be replaced with smells of new paint, new concrete, new carpet, and regulated temperature-controlled environments. Sounds though, sounds can be preserved, and these sounds become echoes when digitally recorded standing in for a very bodily memory of space. After all, sound is how our city touches us, touches our body by making our very insides vibrate. From the oscillation of our eardrums, to the pounding in our chests and the ringing that remains in our skulls, sound is by definition a corporeal experience.

Tan Pin Pin’s Singapore GaGa is mostly concerned with city sounds of a subtler nature: busker songs that wind their way around our hearts, the cacophony of footsteps in an underpass, the specific hollow echoes of void decks and an eclectic range of songs that reflect the city’s polygot, cosmopolitan, postcolonial nature. Re-watching the film is letting the city caress you all over again, but with the sad awareness that even filmed only nine years ago, Tan’s film is already a dated, historical document. Her insistence on our focus on the aural however, makes for a particularly visceral nostalgia—although it also begs a few questions: what does it mean to be touched by an echo of a past Singapore? And can an echo ever really replace what is lost, or is it, as the theorist Joan Scott suggests, a repetition which “constitutes alteration… the echo [which] undermines the notion of enduring sameness that often attaches to identity” (291)? Is it somehow, radically, even more than the material reality that initially produced it? Every time someone watches Singapore GaGa, sitting through its fifty-five minutes of contemplative, non-narrative musings, we pay tribute yet again to our complicated histories and listen better for their echoes in the spaces in our city.

Since Tan’s film, there have been many other attempts at reclaiming the complexity and sociality of Singapore’s spaces. Aside from Tan’s own work Invisible City (2007), as a scholar of literature, I find I often turn to Tan Shzr Ee’s genre-bending book Lost Roads: Singapore (2006) as a way of re-experiencing the city as:

a scrapbook—of real and imagined experiences; of half-remembered stories from family, friends and strangers; of interrupted memories; of anecdotes disengaging and dysfunctional; of rabidly untrue rumours; of bizarre signs and notices spotted in unremarkable corners; of overheard conversations and useless laundry lists… throwaway epiphanies that have presented themselves in the course of my travels through ulu1 Singapore. (10)

It is this unpredictable inventory of unverified stories, truncated memories and minute throwaway details that disrupt the orderly, conformist and capitalist spaces of the city. These spaces are resolutely not for profit, whether they are sacred, natural, domestic, fictional, or an unwieldly combination of the above. Tan Shzr Ee’s invocation of them can be seen as a tactic in the de Certeausian sense, and Tan Pin Pin’s modus operandi is similar. Both writer and documentary-maker then, inscribe in their work the power to at least temporarily resist the over-planned and over-determined nature of Singapore. While Singapore GaGa is ostensibly a documentary, it latches on to the similarly random, fragmented and unremarkable—“throwaway epiphanies”. Tan Pin Pin’s use of editing techniques also plays with the temporal nature of sound, silence and memory, often holding on to empty frames and pauses to create a contemplative rhythm that is sorely missing in Singapore’s cityscapes. The medium of Singapore GaGa however, means that we physically re-experience this urban inventory with each viewing. In fact, Tan’s curation of these echoes is such that we might even begin to experience city sounds differently after watching her work—perhaps pushing us to a more intimate conception of our city.

What makes the film’s polyphony so powerful is its eschewing of any grand narrative to describe a city-state whose officials are so obsessed with its teleological progress. Indeed, Tan deliberately creates a cognitive dissonance between the official state narrative and everyday life by overlaying the artificial performance of summiting a mountain (complete with patriotic song soundtrack and fake inflatable mountain) during the annual National Day celebrations with the lonely song of a busker plying his trade in an impersonal covered walkway.

This is not to say that there are no narratives in Tan’s work—there are in fact, one might argue, incredibly important ones. And they are all the more significant for having been hidden, forgotten or just ignored in plain sight for so long. On a meta-filmic level, Tan refuses to impose any overarching moral or message to Singapore GaGa. This means that these corporeal echoes stitched together by her work, leave both the stories and the viewers themselves to find a more complex and nuanced meaning in what it means to make echoes in Singapore’s spaces. This is an ongoing phenomenon, since, as Singapore GaGa demonstrates, what we think of as the present is always becoming the past.

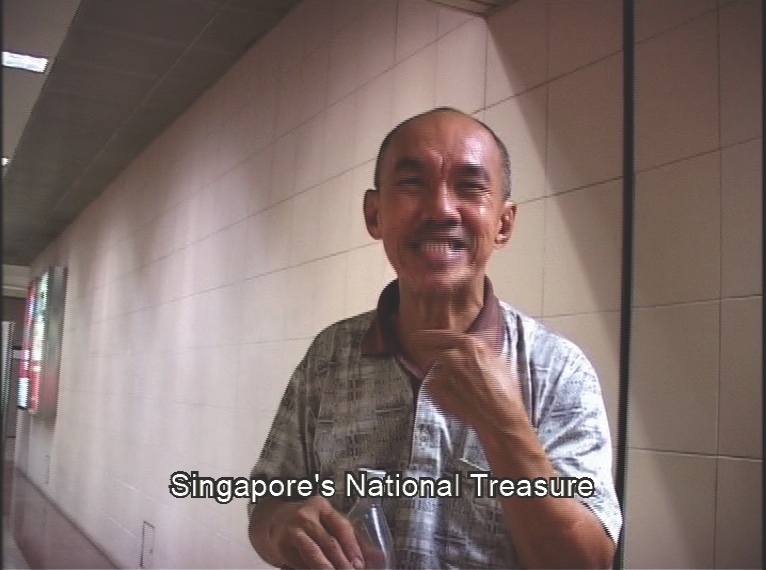

Echoes denote spaces enclosed in some form, making them ubiquitous in a built-up city-state like Singapore. Most of Tan’s film occurs in interiors, private and public (even the void deck and the National Stadium are to some extent interior in the sense that their spaces and echoes are delineated by man-made structures)—with the notable exception of a scene towards the end of the film where groups of unnamed people release lighted lanterns into the sky. What follows in these notes then, is a brief revisiting of these spaces of the film and a re-consideration of their echoes both literal and metaphorical. This means focusing on certain parts of Tan’s film at the expense of others—certainly a whole other essay can be (and needs to be) written about Tan’s rediscovery of the stories of the harmonica player Yew Hong Chow, the communist guerilla fighter Guo Ren Huey and the ventriloquist Victor Khoo. But what piques my particular interest is how Singapore GaGa inhabits the spaces that we all share and pass through every day: the covered walkways, underpasses, trains, void decks, streets, and taxis in a constantly kinetic city.

Here is where the city touches us most, where its sounds echo in our bodies, and yet where we are, as Margaret Leng Tan notes, the least aware since “we’re too busy listening to the thoughts in our head.” This is a brief, fragmentary inventory, an echo of other echoes:

Covered Walkway

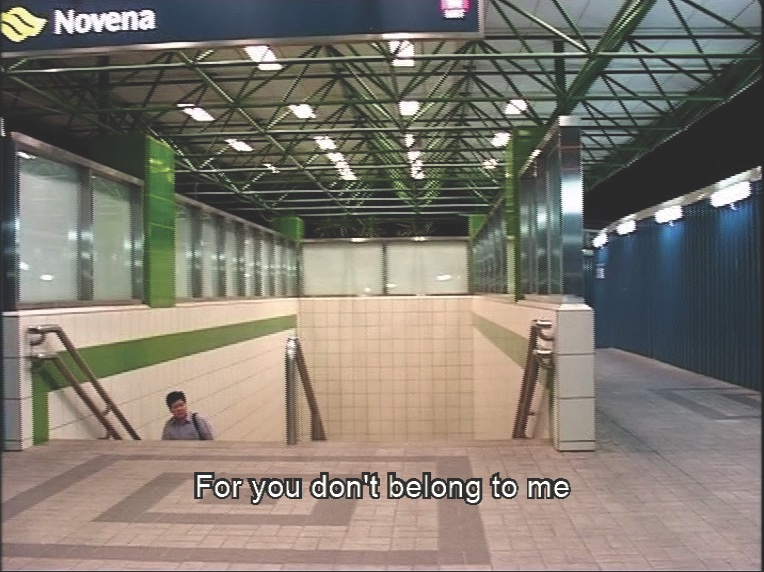

One of Singapore GaGa’s most deliberate cuts—the one that shows an authorial hand immediately in this documentary—is the fade from an audio track of exploding fireworks—the most obvious symbol of patriotism and success in Singapore to the opening chords of the song “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights” performed by the busker Melvyn Cedello. The boom and echo of fireworks, perhaps a little more tinny and canned on screen than in real life, is an annual occurrence in Singapore, and is in fact something that most of us only experience on television. Yet, Tan plays with a deeply ingrained association between fireworks and patriotism in the Singapore psyche, with all its childhood inculcation of national songs, echoing unbidden in our heads. What is everyday life in Singapore however, is but emerging from an MRT2 station into a temporarily covered walkway to come across a busker who is being studiously ignored by all the passers-by. The walkway is a liminal space of transition which makes Tan’s cut to the interior of a plane landing in Singapore all the more logical. They are both places we all pass through, their enclosures echoing with emotion, their time limited and fleeting. The fact that the walkway is boarded off for further construction by sheet metal also highlights the instability of this space, its limits oddly defined by Cedello’s echoey song. His song is makes us realise that even this non-space, this abstract space, is actually a space of potential, of sociality, of the city.

Underpass

The indifference that greets Cedello is the same one that the busker Gn Kok Lin faces—and in these scenes, in what looks like a downtown underpass just outside a train station, Tan is careful to show the low, claustrophobic ceilings and the closed circuit-camera that seem to pin the people down as they walk rapidly to their various destinations, oblivious to Gn’s enthusiastic performances. His use of the harmonica and popular tunes pierces through the white noise of footsteps and the murmur of the crowd.

Tan’s increasingly rapid jump cuts in this scene turn the ordinary into a rhythmic symphony, one that is cut short by the intervention of an SMRT official—a reminder that public space or a commons has to be actively sought out and created in Singapore. But how can one miss something that has not been there for so long?

Tan’s film here takes the everyday aural experience of footsteps, the diegetic music of the busker and transforms another anonymous space into one resonant with life and meaning: a subterranean tunnel suddenly awash with the carnivalesque.

Void Deck

The scene of avant-garde pianist Margaret Leng Tan playing her toy piano in an Ang Mo Kio void deck3 is perhaps the only “staged” scene in Singapore GaGa. In a sense, this makes it the heart of Tan’s film and crucially, a moment of fictionality in what is ostensibly a non-fictional documentary. Having a celebrated experimental pianist set up a toy piano in the void deck of a public housing flat and proceed to perform John Cage’s notorious 4’33” becomes, arguably, a moment where the fantastical encroaches onto the everyday. And the pianist’s choice of music, or rather performative silence, works almost in the genre of magical realism, where the quotidian sounds of the most ubiquitous space in Singapore are amplified and rendered disproportionately significant through the sheer doggedness of our collective focus. This scene turns up the volume of silence; it reveals the minuscule complexities of space produced by the sounds of the environment, what Margaret Leng Tan later calls the “music of the environment.” This moment of fantasy is inherently and intensely participatory in nature. Much of Singapore GaGa invites us to listen to the city’s echoes, but it is in this heart of the movie where we are almost forced or aggressed into doing so. Part of this is of course due to the nature of Cage’s work: 4’33” is a rather difficult 4 minutes and 33 seconds of arbitrary silence—Margaret Leng Tan recounts, in the film, how her first performance of the piece in Singapore, led to an audience member angrily storming out, which she says “was just perfect!” Yet, Tan’s film adds another meta-layer to this, as audiences are expected to sit through a single unwavering shot frame of performer and piano, letting our own minds turn up the volume of the background noise in the scene: the shuffle of feet, the cries of birds, the rustle of leaves, the chatter of inhabitants in and outside the frame. We are called to, indeed coerced into becoming fully aware of this filmic space, through the very bodily experience of sound.

Street/Taxi/Radio

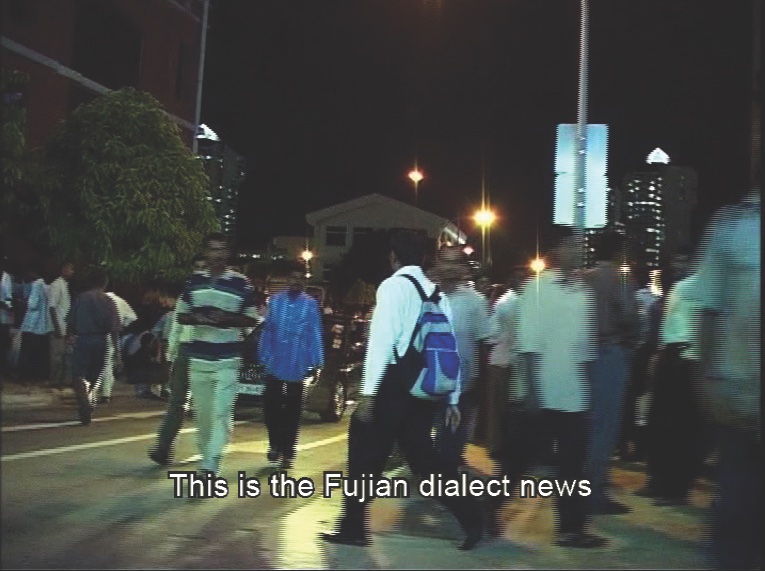

But of course, this moment of singular focus is a moment of fancy—much more in keeping with the rhythms of the city is Tan’s layering of multilingual textures in one of the film’s most complex transitions. It begins with a simple tracking shot of Serangoon Road in Little India where scores of migrant workers are milling about. The sound that cuts above all of the bustle comes from a bus attendant shouting into her loud hailer—her repetitive call of “Kaki Bukit! Kaki Bukit!” while literally naming the destination of her buses also reflects the complex geography of migrant labour as it crisscrosses the island. These echoes illuminate how transnational flows of labour redefine these spaces. But not content with one view, the film reveals that the camera’s perspective comes from inside a taxi.

The sound in this segment then abruptly switches to the cocoon-like atmosphere in the taxi: the low hum of the engine and air-conditioning coupled with the deeply nostalgic sounds of a news bulletin in a Chinese dialect. In this scene, Tan offers a distillation of Singapore space; her artistic gesture renders the moment uncanny and highlights the multiple layers of soundscapes in the city, which in turn reference a space at the crossroads of many Asian cultures, histories and classes. This is a complex spatio-temporality—and Tan’s distillation of this single moment, jolt us back into a recognition of the heterogeneity of our spaces.

The film’s transition here to the air-tight, sound-proof space of the radio studio is particularly fascinating; the studio broadcasting the Chinese dialect bulletins is a distinctly heterotopic space and one that carries the burden of so many alternate voices and histories. In a sound-proof studio, there are no echoes—yet the voices of these old tongues continue to echo all over the island, as evidenced by their presence in moving taxis. These voices, available for a limited, contained time and space each day, bring to mind a plethora of lost stories, voices of grandparents, babysitters—languages suddenly given a brief flash of recognition when used in official tones for news: economic reports, stories of crime or government policy. One becomes aware of how these are not just languages of transaction, intimacy or the familial—they are also rich with possibility and technical detail. They have the ability to be in fact, both private and public—rendering a misguided debate over a “mother tongue” moot.

Watching and Re-watching

For me, the twin emotions that are evoked and re-evoked in my watching and re-watching of Singapore GaGa are discovery and loss, uncovering and then losing these already disappearing sounds. Are these echoes more or less than their original sources? In any case, their immortality is ensured by their place in Tan’s work, their deliberately associative meandering defying any attempt at a grand national narrative. The film begins and ends with the National Day Parade and the busker Melvyn Cedello’s rendition of “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights,” a looping echo of the film’s echoes. In the covered walkway, passers-by seem more taken by Tan’s camera than Cedello’s music; counter-intuitively Singapore GaGa nudges us ever so gently to pay more attention to the latter—the source of the recording, not the method or recording itself. Is this at all possible? We are left only with an echo, an echo that changes with us as we listen to it over and over again.