C. K. was a friend from National Service1. I was a trooper and he was a medic from another platoon in the same company. Even then, I remember having chatted with him on various occasions. Neither of us particularly enjoyed national service, but he had a cheerful disposition, which might have been his coping strategy. After our discharge from the army in 1993, we kept in minimal contact. I learnt that he became an award-winning journalist and an occasional film actor. On November 3, 2012, in The Straits Times, for which he once worked, I read of his death. He had been found dead two evenings earlier on his bed in his single-occupant apartment; a doctor certified that he had died of heart failure. He was 39 years old.

I gagged upon reading about C. K.’s death. Perhaps it was my body’s gut response to the sad and shocking news. He was a peer, a year younger. His diabetic condition reminded me of my mum’s and my own possible affliction of the same. I became aware of my minuteness, mortality and vulnerabilities, especially since I was living alone in my personal studio during the harshest winter ever in Berlin: I could well be in C. K.’s shoes anytime.

Regardless of differences in living conditions and belief systems, most people are afraid of dying. I think there are three main reasons why people fear death. First, they fear the unknown; those who think there is heaven fear what they will get in hell. Second, they fear the pain before death. Third, they fear losing the things they have in this life—the pleasures, the material things, their loved ones. Furthermore, people don’t like dying alone because, as a conclusion to life, dying while having people around you means you have had a well-lived life. Dying knowingly alone means you are weird or you have not lived well. Dying helplessly alone implies some regret in life.

Before learning of C. K.’s death, I was researching into solo passing as a largely academic exercise. Around that time, I was in the midst of preparing for my solo exhibition (entitled Some Detours), which was a requirement as a resident artist at Künstlerhaus Bethanien in Berlin. Aiming to map out the variety and complexity of solitary situations as a way to editorialise my own solitude, I had planned to produce and show three new works: a set of paintings of floor plans referring to solitary spaces, from the series Dwelling; Skeletal Retreat No. 1, a sculpture of the framework of a tree house; and, Corridors No. 1: Solitude, a collection of texts on solitude. For this purpose, I had already started a small archive of news clippings about people who had died alone. The art pieces planned were abstractions of my ongoing research.

C. K.’s passing grounded things in reality. Instinctively, I started expanding and systematising my existing archive of solitary death case studies. With the help of a research assistant, I amassed more news clippings of lone deaths and disappearances and had the information keyed into specific cells on a spreadsheet. It soon dawned on me that another new work had to be made.

The philosopher Gilles Deleuze observes that domestic cats know better than humans how to die: They will slowly walk towards a corner before stopping, then quietly collapsing and passing out for the last time; some even leave their owners’ home, as if wanting their departure to be a private and fuss-free affair. That dying alone seems less an issue for cats than it is for humans led me to wonder: Did C. K. suffer much, or did he die peacefully, or cheerfully even, in his sleep— which is, for some, the most ideal way to go? Did he prefer leaving alone as he did, or with loved ones around? Could C. K.’s lone death be less wretched and terrifying than I had first imagined? Why should C. K.’s death be a matter of concern for the rest of us anyway? I wanted to make a matter-of-fact piece to work through my questions about dying alone. And I wanted it to be as indifferent about dying alone as cats appear to be.

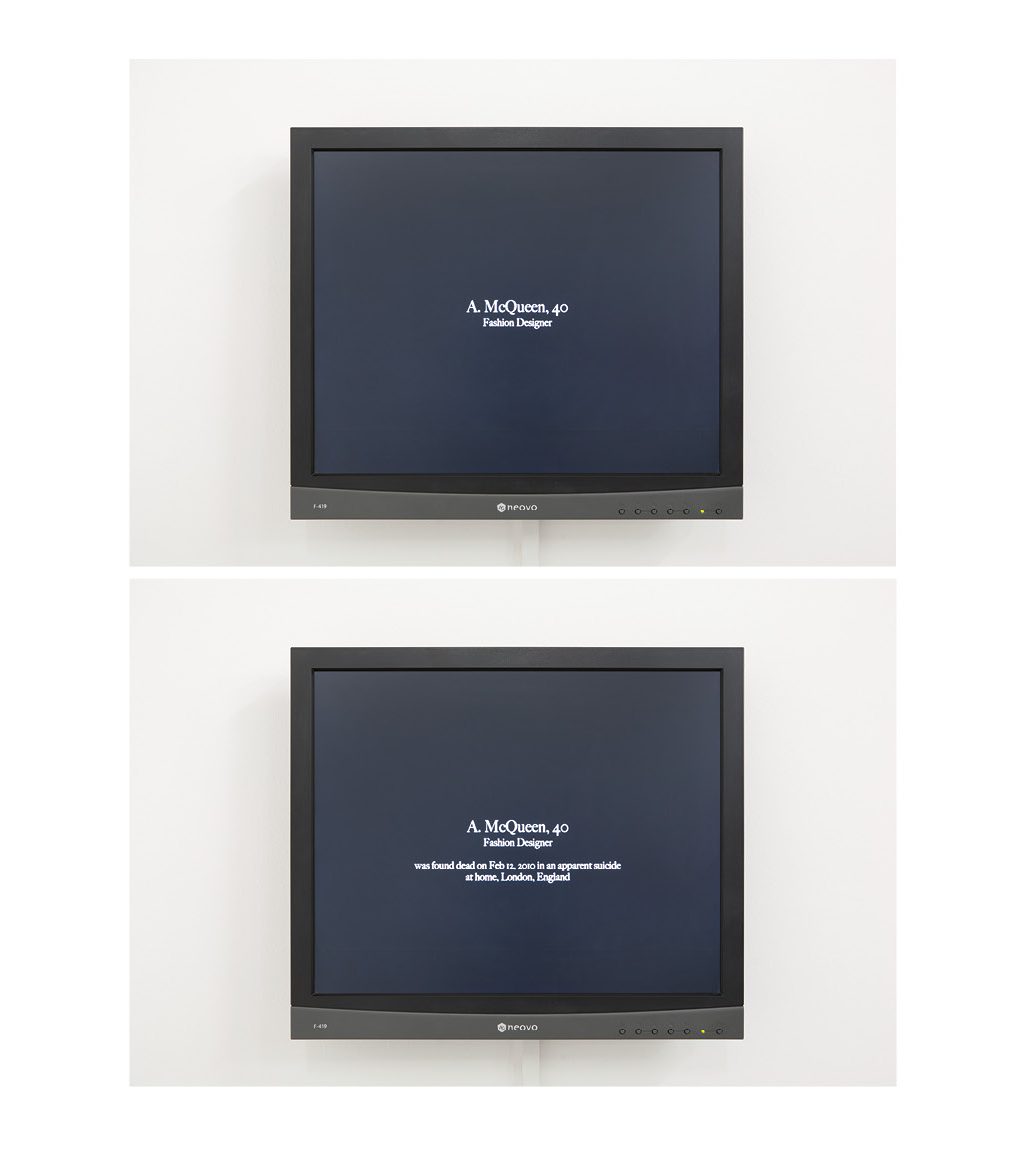

The eventual piece, entitled Gone Solo, is a fourteen-minute video obituary of lone deaths or disappearances. It consisted only of text—no image or sound—collected and selected from the mass media about people who died or were last seen alone.

Of the hundreds of case studies of solo goers in my archive, about forty made it into the work. My selection was based on diversity: a variety of age groups, ethnic backgrounds, places and time periods of death, occupations and contexts was as important as a mix of famous names and unknown ones. I initialised the first names as I did not want the obviousness of the deceased’s gender to hinder viewers’ identification. Each case study appears through a two-step fade-in: First the deceased’s name, age and profession (or social category) appear at the centre of the otherwise black screen. Then the cause and place of death follow below, if not the context of the discovery of his or her body or body parts. The order of appearance, alphabetical by first names, is aimed at conjuring the most startling juxtapositions.

Quite a few featured cases involved a time lag between death and discovery. This often happened to people who lived alone (such as Y. Vickers, a former Playboy model, who was found in 2011, a year after dying at home), or those involved in unfortunate situations like murders (R. Boyd) and suicides (fashion designer A. McQueen).

Not all the deaths were necessarily painful and long-drawn. D. Carradine, an actor and martial artist, was found dead in a hotel room in Bangkok of autoerotic asphyxiation.

The situation-specific deaths were especially poignant. The bookseller C. W. Law was crushed to death in 2008 by falling books in his stock room in Hong Kong, giving a most ironic twist to the common wish to die in the company of one’s loved ones. Or consider A. Hugeuenard, whose life work was in nature conservation and who died a day after a fatal bear attack in a national park in the USA. G. Park passed away in his prison cell, as did many of his fellow convicted murderers.

After reading a few cases, as I have observed, the viewer will get into the rhythm and start making calculated guesses and precise recollections of how each person had died. At times, they are correct, especially for famous cases like B. J. Ader’s disappearance at sea on a lone sailing trip between Massachusetts and Ireland. Most of the cases, however, throw viewers off their expectations. These include those bordering on the bizarre: Pope J. Paul I, who died seated upright, must be one such case, as is A. E. Lim, who was found dead on the wires of a generator. Sometimes, no body was found. Only two pieces of bones of S. Fossett, a businessperson and aviator, were found a year after he was reported missing on a lone flight. There are even cases where the lone death occurred in the busiest of public spaces: Architect L. Kahn was found three days after dying of heart attack in a toilet in a train station, and an unnamed lone traveller was discovered dead sitting among fellow travellers on a bench in a train station.

Gone Solo is not an expression of admiration for or an appeal to sympathise with those who had died alone. It is perhaps more a token of gratitude to those people who had found themselves in situations of solitary departures, whether intentionally or helplessly, gracefully or wretchedly, happily or miserably. They have nothing to teach or tell us. Even if they set out to impart something to us, I doubt we can understand what they have been through. So why am I grateful? I thank these soloists, reclusive leavers and vanishing acts for rehearsing on our behalf the end of our own meagre lives.

Michael Lee

Gone Solo (14 of 90 video stills)

Digital Video – 14min

2013

Edition of 6 + 2 AP

Photo: Ute Klein