Music sits firmly at the core of Song-Ming Ang’s artistic practice. The subjects of his artworks have included pop-stars, music playlists, and aural ‘guilty pleasures’. Rather than focusing purely on the sonic dimensions of music, Ang frequently examines the reception of music, what it means to us and how it shapes our selves as cultural beings. Listening is rarely simply listening. We oscillate between the beat of the music, its lyrics, melody, how it makes us feel and the memories and emotions that it triggers. A connection is formed between the sound of the music, and what is lodged within us.

Ang did not become an artist via the usual art school route. He has a Bachelor of English Literature from the National University of Singapore (2005) and a Masters in Aural and Visual Cultures from Goldsmiths College (2009). This diverse background is reflected in his approach to making art: Ang does not limit himself to one particular medium or method, working instead from an idea for which he tries to find the best process and outcome. His practice has spanned sound to writing, painting to video, interactive performance to reassembling an entire piano (Parts and Labour, 2012).

Ang engages primarily with popular music. By ‘popular’ music, I specifically mean music that, according to Theodor Adorno’s definition, adheres to a standardised formula, as opposed to ‘serious’ music1, which includes national anthems, church hymns, jazz (famously railed against by Adorno), rap, rock and the genre of pop music. All of these forms of music are subject to their own particular structure, though one that evolves and shifts over time.

A Metallica fan, versus a Bob Marley fan, versus a Celine Dion fan all carry very different cultural stereotypes. Our musical choices allow us to cultivate our own identity, both through what we relate to, and what we exclude. This is seen clearly in Ang’s performance Guilty Pleasures (2007), which explores musical shames in the format of a listening party. Here, Ang engages his audience to share and talk about a song that they consider to be their guilty pleasure, before playing the song for all to listen. It has since become a published book containing selections from a hundred contributors: artists, curators, musicians and writers. The project highlights the way that music is coded so that certain types of music imply certain types of people. In the nineties in Singapore, when Western rock was ‘in’, seventeen-year-old Ang suddenly felt ashamed of his love of Leon Lai, one of the biggest pop-stars in the Mandarin/Cantonese pop circle2. Sometimes the music that we love does not fit with the external image that we wish to portray or the group that we wish to fit into, which is often why we do not dare to admit to certain private pleasures.

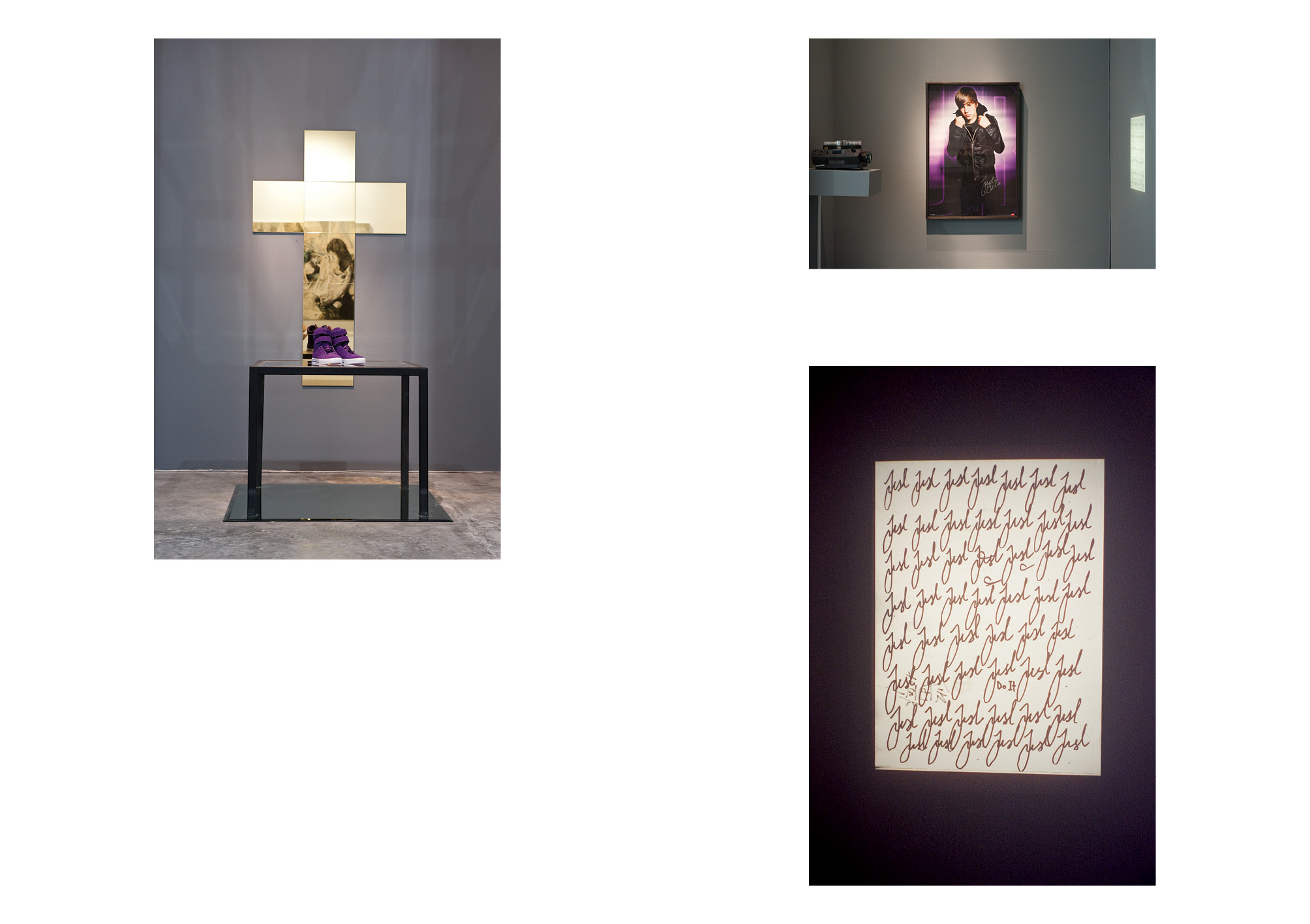

Fulfilling a very specific stereotype of tween idolatry is Justin Bieber, a teenage singer who has been transformed into a product through the careful cultivation of symbols surrounding him—initially, and most notably, his hairstyle. Ang’s installation My World (2013) appears as a shrine to the pop icon. The piece includes gold-tinted mirrors arranged in the shape of a crucifix, purple high-top sneakers identical to the singer’s atop a glass table, an autographed poster of Bieber, a silver ‘painting’ made from the endless lines of the marker pen used to sign the poster, and finally a 35mm slideshow that document three months’ worth of Bieber signatures practised by Ang.

The revelation that the poster is not the real deal but instead the final outcome from the painstaking signatures by Ang the imposter, emphasises that in the music world there is a doubling between the real Justin Bieber, who exists somewhere eating, sleeping, breathing; and this other fake constructed Justin Bieber which has become a greater force composed of symbols that we can primarily buy: the haircut, sneakers, drop-crotch pants. On closer inspection we also see that one sneaker is stuck down with a piece of chewing gum, implicitly suggesting that not all is as it seems and this constructed shrine (and by extension Bieber’s constructed image) could all fall down at any minute. Ang simultaneously positions himself as pretend-fan by making the monument, and imitator of the symbolic Justin Bieber. The gap between the ‘authentic’ version and the fake of Bieber & Bieber, and Ang & Bieber share a tenuous link, where the imposter can potentially take on a life of its own and overtake or replace the ‘real’. Music here is notably absent, acting instead as the spark for the constructed image of Bieber and therefore becoming intertwined in our consciousness with these symbols.

Following a more innocent idea of music that is emotionally transferred onto a treasured object is Ang’s Stop Me If You Think That You’ve Heard This One Before (2011). Here, the vinyl album sleeves of Belle and Sebastian, indie darlings of the early noughties, each sit below a painted watercolour circle of a single hue that is derived from within the original album cover. Belle and Sebastian are one of Ang’s personal sentimental favourites. Here, album covers become precious objects, imbued with the music that they represent, and can mean almost as much as the songs themselves for the memories of a particular time, place and emotional connection that they generate.

Despite the Belle and Sebastian album sleeves, the artwork takes its title from The Smiths’ song “Stop Me If You Think That You’ve Heard This One Before”. Indeed, it turns out we have ‘heard’ this one before. In a clever double twist, Ang’s work is an appropriation of Jonathan Monk’s 2003 piece of the same title. Visually, the main difference between the two is that Monk uses The Smiths’ records while Ang uses Belle and Sebastian’s. It is almost as if Monk set himself up for Ang’s appropriation by using this title about repetition. Given the popular music subject of the work, perhaps it is more appropriate to step outside art world terminology (appropriation) and instead suggest that Ang has created a ‘cover version’ of Monk’s artwork Stop Me If You Think That You’ve Heard This One Before, performed by Belle and Sebastian, produced by Song-Ming Ang.

The ‘cover version’, where a song originally recorded or made popular is recorded by somebody else, is a unique example of music’s ability to transport us or even split us in two (metaphorically of course). In Ang’s recent performance Can’t Help Falling in Love at Insitu in Berlin (2013) he spoke about how, when listening to a cover, he still hears the initial version echoing underneath the track; or in his words, ‘experiencing one while thinking of the other’. He compared Joy Division’s dark and despairing original, “Love Will Tear Us Apart”, to Nouvelle Vague’s troppo-café-lite version. Ang couldn’t resolve whether or not this was an insult to its predecessor as it completely erased the melancholy and weight of the original; or whether it was a pleasant tune unto itself, perhaps adding light to the dark. For Ang, it is the tension between the original and the new version that determines the value of a cover version. Despite the sweetness of the Nouvelle Vague version, in this case it is impossible to listen to it without hearing the Joy Division version. Like a ghost, the original piece haunts it.

Music is particularly good at conjuring spirits. David Toop writes: “Listening… is a specimen of mediumship, a question of discerning and engaging with what lies beyond the world of forms.”3 It allows us to do the impossible, to travel back in time, to feel things that we have once felt and to imagine things that we may one day feel. The voice of a dead singer can be brought immediately to us via a stereo, just as a particular track may take us to a former version of ourselves, in a different location with people who no longer exist in our lives.

Ang deliberately bridges this psychic gap between the past and present in Be True to Your School (2010), which is a five-channel video work where former students of a Japanese primary school attempt to remember their school song. Lines include “Looking up Mount Tsukuba, I set my dreams high as the mountain. Dedicated to study with high spirits are four hundred robust youths”. In the videos, there is a disparity between the aspirational words that the men sing, and their older bodies in adult attire. One can’t help but wonder whether or not they have indeed fulfilled the hopes and dreams outlined in their school song.

Looking then at the men’s faces smile and fill with pride as they recall the song lyrics, they seem to turn back into their schoolboy selves. It is as if a spirit is conjured up and the young boy and older man coexist for a moment in time. Similar to what we see in the video, The Fugs’ band-member Steven Taylor writes: ’]“I had experienced in the punk clubs, the sense of being in-between, neither inside of nor outside of myself, in a place where individual identities are not lost in undifferentiated wholeness, but rather seem to phase in and out.”4 Through the recollection of music, these men can be multiple selves: not only do they themselves experience this, we as viewers can also see it.

These fluid identities spoken about by Taylor allude to the fact that music can transform and transport. Music not only activates multiple beings within us; it can be used by us to form our own identities (as we have seen earlier with our guilty pleasures) as well as consciously or unconsciously summon up past feelings and experiences. Ang’s practice points towards the notion that music does not function simply unto itself. Through his exploration of our diverse relationships to music, we see the various shifts that music undergoes within us: from the symbols that overtake the original sound, as with Justin Bieber; and the sentimental attachment to physical objects such as album covers; to the more complex overlays of past and present in cover versions and remembered childhood songs. Music has a tendency to separate itself from its source and mutate within us. There is a split that occurs between the music itself, its multiple meanings and the way that it adheres to our psyches and surrounding objects. In Ang’s works, echoes ring out from the original sonic triggers and duly assume lives of their own.

Be True to Your School (2010)

Five-channel video (each video approximately 2-3 minutes)

Guilty Pleasures (2007)

Listening Party

Photo credit: Jan Rothuizen

My World (2013)

Installation: autographed poster, slide projection, framed photograph, marker painting, gold-tinted mirrors, glass table, clear mirror, sneakers, chewing gum

Photo credit: Deanna Ng

Stop Me If You Think That You’ve Seen This One Before (2011)

Seven water colour paintings and seven 12” vinyl records.

Each painting 52 x 52 cm (framed). Each record 32 x 32cm.