Emergencies, like most human phenomena, repeat themselves. Sometimes, they repeat in the same place in another time, or in another place at almost the same time. However, they also repeat themselves in an imperceptible form that essentially emerges out of the same but hidden structural mechanisms. When they do repeat or show up again, it may be shocking to those who do not recognise their earlier incarnations; maybe because such emergencies do not evoke sharp consciousness or memories of images or sounds in a daily life-flow—when time passes smoothly and individuals do not experience the time and space of this emergency collectively—thus the boundary of a daily emergency is limited to the personal space and do not travel across other domains. They are also not documented in a way to be remembered and recognised in the future as an emergency, or a memory of an emergency.

Emergencies in an urban setting like Shanghai, with a population of 250 million, bear all the above features.

Photo by Chen Yun, 2005

On a sunny day in 2005, a young man sitting in a bench reading his mobile messages (in an era before smart phones) while a sculpture of the famous author Ding Ling (땀줬) sat next to him, reading a book.

For a term paper, I paid several visits to Duolun Road, a street in Hongkou District, in north Shanghai in the autumn of 2005. The street has been known as Duolun Road Cultural Celebrities Street since when I was in high school. This long title, though sounding a bit odd in English, makes good sense in Chinese and has been established over the years. In fact, the widening of this once narrow pass was a result of demolishing earlier houses and architectures. After the transformation, the street was made pedestrian-only and new sculptures of famous literary figures (or cultural celebrities) were set up to commemorate the left-wing literary movement once happened here in 1920s and 1930s.

Duolun Road (뜩쬈쨌) was constructed in 1912. Its original name was Darroch Road (注있갛쨌), after the British missionary John Darroch (1865-1941), who fled to China like many foreign missionaries in the early 20th century and later purchased this piece of land to attract investors and businesses. Although this road and its surrounding neighbourhood theoretically belonged to the Chinese settlement, it was built as one of those extra-settlement roads by the colonial government of Shanghai Municipal Council (1854 – 1943). As people could build houses without planning permissions, the road was soon filled with villas of exotic styles, in lanes paved by developers and businessmen.

The convenient location of this area and the relatively cheap cost of housing made it easier for a particular kind of writers and artists to live and work here. It is next to the major Japanese settlement in Shanghai (Japanese residents who had migrated to Shanghai continuously since 1870s) and was filled with numerous cinemas and publishing houses. The most well-known group is called The Chinese League of Left-wing Writers, a progressive literary organisation spearheaded by Lu Xun. It was by then an underground literary group, active between 1930 to 1935.

That summer of 2005 the street looked quiet and beautiful. It was by no means a busy street. In fact, it was much quieter than any of its narrow backstreets. In one of my chats with local residents, an old gentleman complained that the newly paved surface of Duolun Road made it extremely slippery for cyclists and pedestrians; one could simply stand at the iconic L turn of the street and witness them falling down during rainy days. Residents recall the old surface of this road, made of tiny pebbles and stones cast in mud, when falling raindrops over this surface added to the rhythm of traffic. People hardly fell down on Duolun Road in those days.

Eleven years later in 2016, Shanghai Biennale was curated for the first time in its 20 years of history by a non-Western international curator/group Raqs Media Collective (based in Delhi, India), and I was invited to join the curatorial team. I proposed to curate a project called 51 Personae, an off-site programme consisting of 51 events in the city of Shanghai based on the life experiences and potentials of ordinary people. An open call was announced on the Labour’s Daily (the official newspaper of Shanghai Federation of Trade Unions) on 5 May, days after the International Labour Day. It occupied half of a full page in the Culture and Sports section.

From the first month of 2016 till the beginning of the 11th Shanghai Biennale in November, we have been busily looking for the potential “personae” around us. Open call is one way (although 80% of the applications are from artists with their standard proposals of their works for an exhibition) and personal channels seem to be no less important than the public channels. One day, I was told by a friend of an artist, Eileen, who has recently moved out of her rented apartment in Jingyun Li, Hongkou District. She had sublet from Ms. Cheng Shaochan (넋紹窄), who was also given notice to leave the building. He briefly described Eileen’s situation to me, and it seems to be a typical story of demolition. A major difference is that this occurred in Jingyun Li, an area famous for being one of the former residencies of Lu Xun and his left-wing writer friends and the conserved neighbourhood architectures. Then, why was Ms. Cheng forced to relocate? I have been observing and interviewing such cases in Shanghai since 2013 and I strongly feel that such an ongoing story should become one of 51 Personae’s, so that it could be staged, learnt, told, discussed, and documented. Not as part of an official documentation or archive but a story that can be participatory and fluid in its approach. This for me is what 51 Personae as an art project should accomplish.

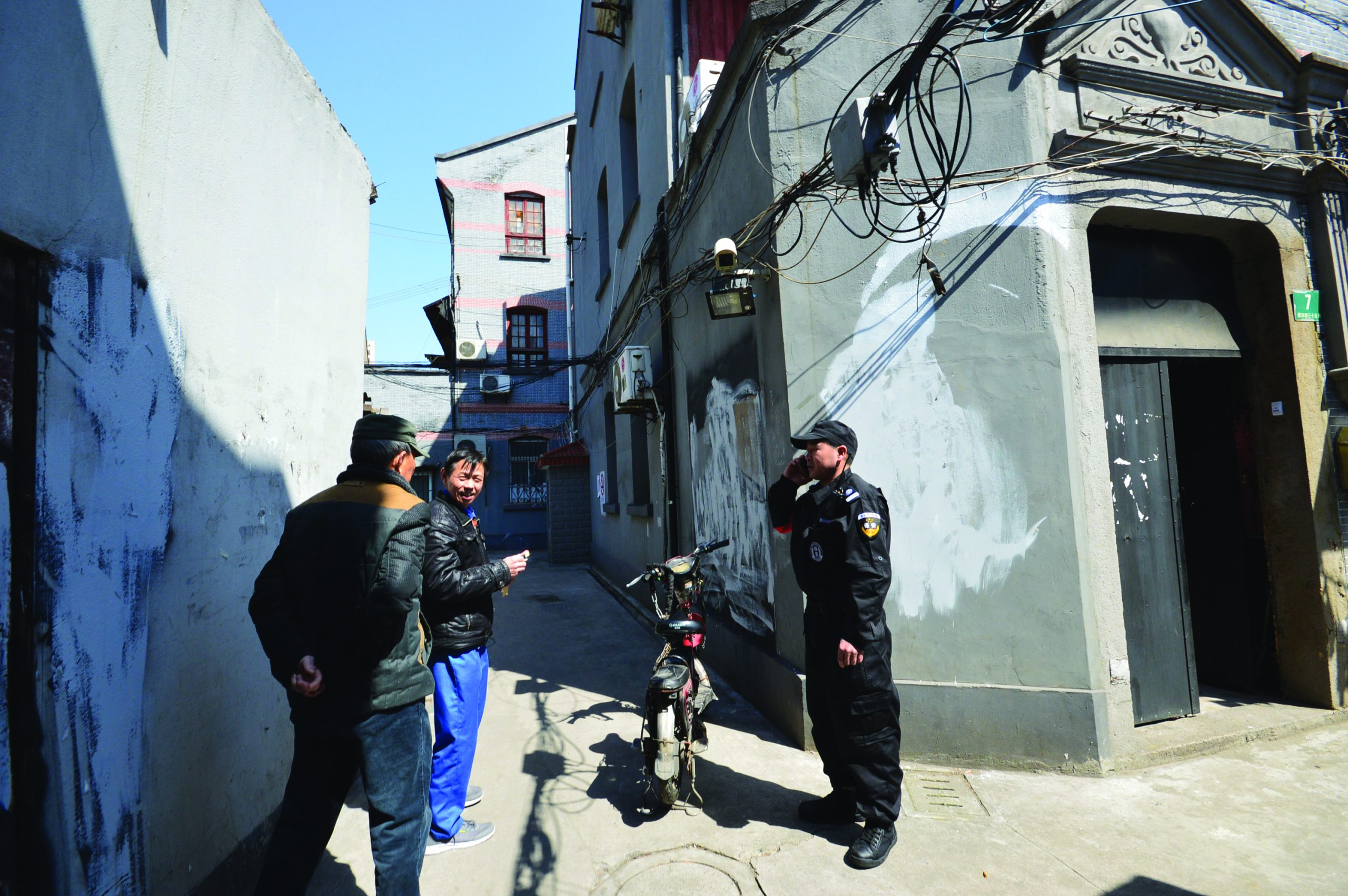

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

With the help of Eileen, I made an appointment with the owner of the house, Ms. Cheng. Ms. Cheng expressed her interest in 51 Personae even before we met. On 23 August 2016, Eileen and I took Shanghai Metro Line 3 and dropped off at Dongbaoxing Road Station and walked through a ruin which was once a vivid neighbourhood since 1920s. Metro Line 3 is an elevated metro line that shares the route with Songhu Railway (1876 – 2000) in its northern passage and it is exactly this railway that brought prosperity to Duolun Road, North Sichuan Road and Jingyun Li. The railway served as an infrastructure attractive to residents and developers in the 20th century, just like metro lines will increase the price of real estates along its line in the 21st century.

On that summer day, we walked through the “neighbourhood” right at the back of Duolun Road. It did not look like the neighbourhood as I had known back in 2005. The once crowded small streets are deserted except for a few people who seem to be stragglers of the land acquisition or simply who were in the business of recycling the materials and taking over the land for their employers. I wondered what Lu Xun and his friends would feel if they had lived till today. Lu Xun passed away in 1935, before the next page of Shanghai and China’s history. Since most of the houses were constructed with wood and bricks, the demolished materials were recycled back into bricks and wood structures, particularly those used as beams and pillars, which will be collected and sold to third parties—part of the demolition economy.

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

Ms. Cheng, in her late 50s, now lives in a small bedroom on the second floor, sparing the larger rooms for her tenants (one was Eileen who had just moved out, and another girl who lived on the third floor whose belongings were later removed from the house along with the belongings of Ms. Cheng). She now spends half of her time in Shanghai and another half in Minneapolis, where her son lives. The interior layout of this three-storyed Shikumen (literally stone gate) house was largely unaltered, keeping to its original structure, except for the position of the staircase which she shifted from the back door to the front—which she later felt was not an ideal change in terms of fengshui. However, this staircase later served to stage the 51 Personae event.

Before she purchased the house, it had been used as a dormitory for workers in a small factory. Before 1949, she heard that the house belonged to a musician and his family. Like many private houses, this one was obviously acquired after 1949 by the government and thereafter became government estate, of which the government can decide its land use. When Ms. Cheng purchased the right of lease of this public house from the government (represented by a real-estate company), she gained the right to permanently rent this house and use it. All is fine and binding as long as the house exists. The house will exist because of Lu Xun and his legacy but Ms. Cheng was forced to negotiate a deal with the government who now wants the house back for other use.

The first day we met, we talked for two hours—covering her reminiscences from her childhood to the current situation. The conversation was later edited as a first-person narrative and printed out as a brochure for the 51 Personae event on 8 February 2017, during the 11th Shanghai Biennale. Besides the brochure, which participants of the event may take away, books and journals on the modern history of Hongkou and Lu Xun Studies were piled up on her desks and tables. Ms. Cheng had been independently carrying out historical research as a hobby since when she was young. As early as in 1990s, she shared much of her research that gathered important information on comfort women in Hongkou area with local university scholars. However, she does not agree with the one-sided patriotic narrative produced out of these historical materials as part of the nationalism argument that prevailed during these years.

She showed me a letter, she received from The Bureau of Housing Security and Management of Hongkou District, captioned: “Report on the housing expropriation compensation agreement made to Cheng Shaochan.” She has written in red, remarks on this letter such as “robbers and rogues” and “intimidating and threatening.” She underlined “the need for renovation of old houses in locations with poor infrastructure” in this letter and commented in red: “the government creates false names (to legitimise its expropriation of the houses).”

At the end of the conversation, she added that she also wondered why she had never been approached by a decent government officer but only men wearing colourful shorts and slippers, who were in fact employed by the government real-estate company to do the job. Why, after all, did she have to return her place of residence to the government for an unknown cultural purpose? Why could she as an individual not contribute to the cultural character by continuing to live there? Above all, the proposed compensation from the government was far below market value of this house and she could not afford to obtain a similar house here with the compensation.

The street of Donghengbang Road has always been home to a street market.

Photo by Chen Yun

The main gate of Jingyun Li is on Hengbang Road, a lively street which used to be a street market. Street markets have been traditionally an important form of urban life in Shanghai where people purchase daily items and fresh foods in the morning and at dusk. However, since 1990s, it has been regarded as something low and ugly, as if the city can no longer bear such indecency and shall replace them with indoor markets. With the gentrification of the city, and the demolishing of the old neighbourhoods, street markets are disappearing. After Duolun Road became Street of Cultural Celebrities, a grand gate was set up at the back door of Jingyun Li which the residents never use.

Photo by Chen Yun, 23 August 2016.

The Chinese characters of Jingyun Li were written in very humble calligraphy, as humble as the main gate when it was built in 1925: the gate opens to a lower middle-class real estate for residents who want a convenient location but who cannot afford to rent something better. Lu Xun moved here in 1927, only two years after the lane was built. It was a practice for tenants to give a big sum of money to the owner of the estate to acquire the right to lease. Under such a lease, Lu Xun moved into No. 23 Jingyun Li in October 1927. Two years later, he moved to No. 17 while Rou Shi (1902-1931), a young and enthusiastic progressive writer who was supported by Lu Xun moved into No. 23. Rou Shi was killed on 8 February 1931 along with another four left-wing writers in Shanghai, after being betrayed by someone within the Communist Party.

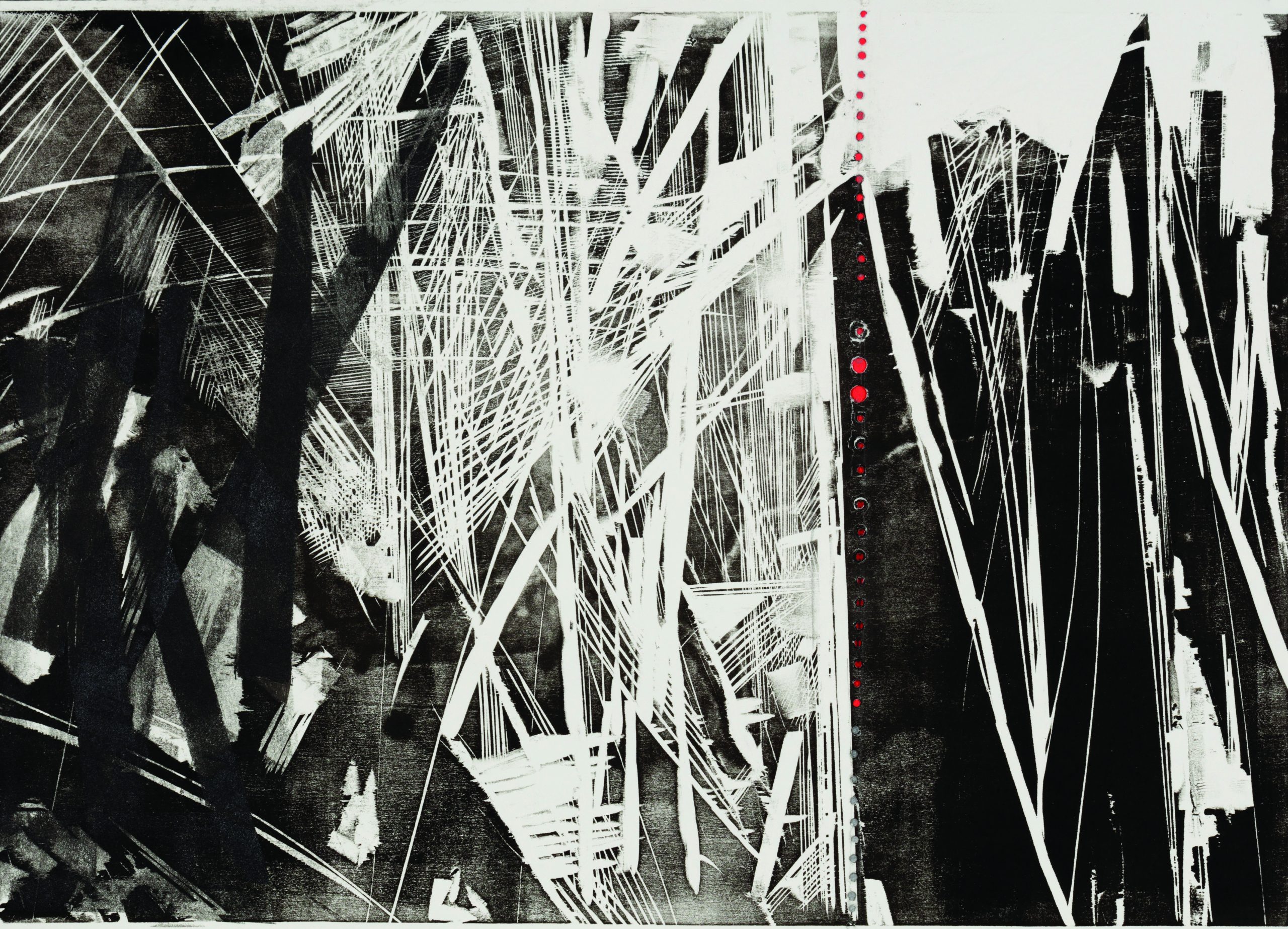

Lu Xun (1881-1936) was the first to consider foreign woodcut prints and to recognise the effective potential of using the medium to serve the needs in China, as propaganda and to promote social change. He is considered the father of the Modern Woodcut Movement of the 1930s and 1940s and a leading figure in modern Chinese literature and education. Through his lectures and writings, Lu Xun called for a new form of art that gave voice and passion to the people: the woodcut print.

A woodcut print by Li Hua (1901-1994), who was regarded by some as the best student of Lu Xun, depicts the scene of a six-day woodcut print workshop hosted by Lu Xun in a rented space not far from Jingyun Li, from 17 to 23 August, 1931.1 The teacher Uchiyama Kakechi was invited by Lu Xun as the instructor and Lu Xun himself did the translation for the younger generation of woodcut print artists. Li Hua was not among the 13 students who had participated in this workshop, which was an iconic event marking the beginning of the Chinese woodcut print movement, but he had been in constant correspondence with Lu Xun since late 1934 from whom he received his instructions on art.

Lu Xun often brought works of German artist, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), to class and till the end of his life, promoted her works in China. In September 1931, to commemorate the death of Rou Shi and other left-wing writers, Lu Xun chose a print by Kollwitz entitled Sacrifice and published it in the first issue of magazine Beidou. This was also the first time that Kollwitz and her woodcut print works were introduced to China.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan, 7 February, 2017.

Ultimately it was Ms. Cheng who curated her own 51 Personae event. She knew what she wanted to do and when it will be done. She set the date 8 February 2017 for the event because that was exactly 86 years after Rou Shi was killed. She selected four woodcut paintings by Zhao Yannian (1924-2014) and said she wanted to know how they would look like if they are enlarged and printed at the two facades of her Shikumen house, within the lane and on the street of Hengbang Road. She knew where these images would go and we would merely facilitate and realise this project as a collective effort.

The day started early in the morning, when a group of open-call recruited participants and our friends gathered in Jingyun Li, ready with the huge plastic canvas which bore the image of the “Madman”. Cutting out the stencil and spray painting, it took almost one whole day for more than 10 people working continuously to finish. But when they were done, the final outcome resembled a book page.

(No. 31), woodcut print, 1985. Photo by Chen Yun on 7 February 2017.

To commemorate the centenary of the birth of Mr. Lu Xun, 1981.

Photo by Chen Yun on 7 February 2017.

Although he was only 10 years old when Lu Xun passed away, and had not been taught by Lu Xun directly like his own teacher Li Hua, Zhao Yannian recalls his connection with Lu Xun’s famous novel A Madman’s Dairy (1911) after the Cultural Revolution:

I read A Madman’s Diary again and again, and realised that the “Madman” is not only not “mad”, but indeed a real person who knows right from wrong.

He was “frank”, “reasonable” and “brave”.

How could the idea and composition of the painting really show the repression and resistance of the madman in the limited space of the painting? This was the first and most difficult problem I encountered. I drew a lot of sketches, arranged them and deliberated them over and over again, trying to figure out the relationship between Lu Xun’s original thoughts and my composition.

In the end, I chose to use the image and temperament of a clear, sensible, brave and confident maniac to portray him. I used a flat knife to carve, emphasised the combination of blocks and surfaces, and created a strong dynamic tone through a large contrast of black and white.

Right: Younger participants of the event sitting on the stairs and chairs listening to a neighbour (in the middle, holding a newspaper). Photo by Chen Yun, 7 February 2017.

At the evening of this long day, more people joined the gathering for the screening of a short documentary film (shot by Li Yafeng and produced by 51 Personae) on the accounts of an old gentleman Mr. Dai Fengwei (left in green of the left photo) who introduced the history of Gongyifang (무樓렌), a nearby neighbourhood also under expropriation. Mr. Dai was also a man who refused to leave, but on that evening we were told that he has been forcibly evicted by a mob of government-employed gangsters and expelled from his home where he lived since when he was five. The presence of Mr. Dai was a precursor of what woud happen to Ms. Cheng. Mr. Dai passed away one year later but his stories were documented and always remembered when we continue to observe and engage with Ms. Cheng in the days to come.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan.

Photo by Xu Ming.

One day in March 2018, when Ms. Cheng left home to visit Japan, her tenant was forcibly evicted by a mob. All their belongings were removed from the house and the door openings were sealed up with hollow bricks which were light and easy to pile up to form a ‘wall’. Strangely, after one year of rain and heat, the original spray-painted woodcut image at the south facade looked clearer than the year before. What had been washed away was the white paint that had been applied roughly to cover and censor the woodcut print image. What had been added over the ‘hidden eye’ of this image was a police notice.

By February 2019, two years after our 51 Personae event, the woodcut print image was covered by a notice board with one-sentence description of the history of Jingyun Li. A tourist/patriotic route called Lu Xun Trail was curated by the local cultural bureau in the effort to claim the significance of the left-wing literary history. Ironically, by that time, the neighbourhood which once served as both a living space and a protection for those left-wing progressive writers is almost flattened. The backstreet of Duolun Road is left in ruin and the only houses that still stood there were in Jingyun Li. Only cultural celebrities and their legacies remained but were left placeless, and out of place.

Photo by Chen Yun.

Since the house itself will not be torn down thanks to Lu Xun, one rainy winter morning in February 2019, Ms. Cheng moved back to her house with the help of friends. The house was empty. The ACs were gone and the gas, water and electricity had been cut off. Ms. Cheng went to the public service departments and asked to be reconnected with gas, water and electricity supplies. So she got them back, along with other secondhand furniture that can host her again in the house.

One day, she showed me some socks that she knitted when she was teaching a knitting workshop in Minneapolis. I then realised that she is very talented in knitting and has been interested in it since when she was six. And knitting seems to be a productive and positive way of telling her story, which I will not call a personal tragedy, but something that needs to go public exactly because it is not personal in many senses. I suggested that she knit her stories into the socks and share it with others who may be interested in stepping on the oppressive forces all around them. Or, to invite others to put on her socks and share the same stance with her. She soon produced many pairs of socks, some bearing the initiative JYL and the number 7, and some with Chinese characters of Chaiqianban (demolishing and relocation office). She joined us and presented the socks at the abC Art Book fair in Shanghai and at a special booth of 51 Personae at Power Station of Art. The socks, attractive for their unique colours, patterns and forms, were sold for 15-20 RMB and made popular purchases.

Photo by Cheng Shaochan

Photo by Mira Ying

Inspired by Ms. Cheng’s socks, our artist friend, Yingchuan, designed a silk scarf based on a fable that she had written called Max and animals dance in the belly of the big snake; it teaches how to negotiate with evil forces even when one is swallowed by them. The work is called A Letter from Jingyun Li. This picture (above) shows Ms. Cheng under this flag-like silk scarf on the National Day fair at Power Station of Art.

Photo by Emma Mou

Just one month after that, Ms. Cheng found herself evicted again. All her secondhand furniture was gone and moreover, the staircase between the first and second floor was demolished. Ms. Cheng, daughter of revolutionary parents who were buried in the same martyrs’ cemetery as Rou Shi, decided that she will stay in the house on the second floor. She received her supplies by the rope-and-basket system, and by that time, many people including Emma, who had spent a couple of months with her on the third floor (and whose belongings were also removed along with Ms. Cheng’s belongings) gave her support of various kinds. Young people who learnt about her story online came to the house to spend nights with her, in fear that another forced eviction might happen for a third time.

And the forced eviction did happen once again in one night in December 2019. When that happened, she decided to live in the local police station, where she had taken up temporary residence during the last eviction. People continued to visit her at the police station and to give her supplies and support. During the day, she would sit at the very last row of the reception hall, while at night, she will sleep in a smaller separate room with AC. When everyone thought that she would be living in the police station for a few more days till the government sent a representative to negotiate with her, she was unexpectedly brought away by the police to be sent to a custody-asylum in north Hongkou, on Shuidian Road. But since her registration (hukou) was in Shanghai, she did not qualify to be admitted there. Consequently, she was sent back to the police station; however this time, she decided to sleep in front of the Sub-district Office of North Sichuan Road) just adjacent to the police station. The following morning, she was brought by force into the Sub-district Office where she lost connection with all the relatives and friends for 11 days before she was released.

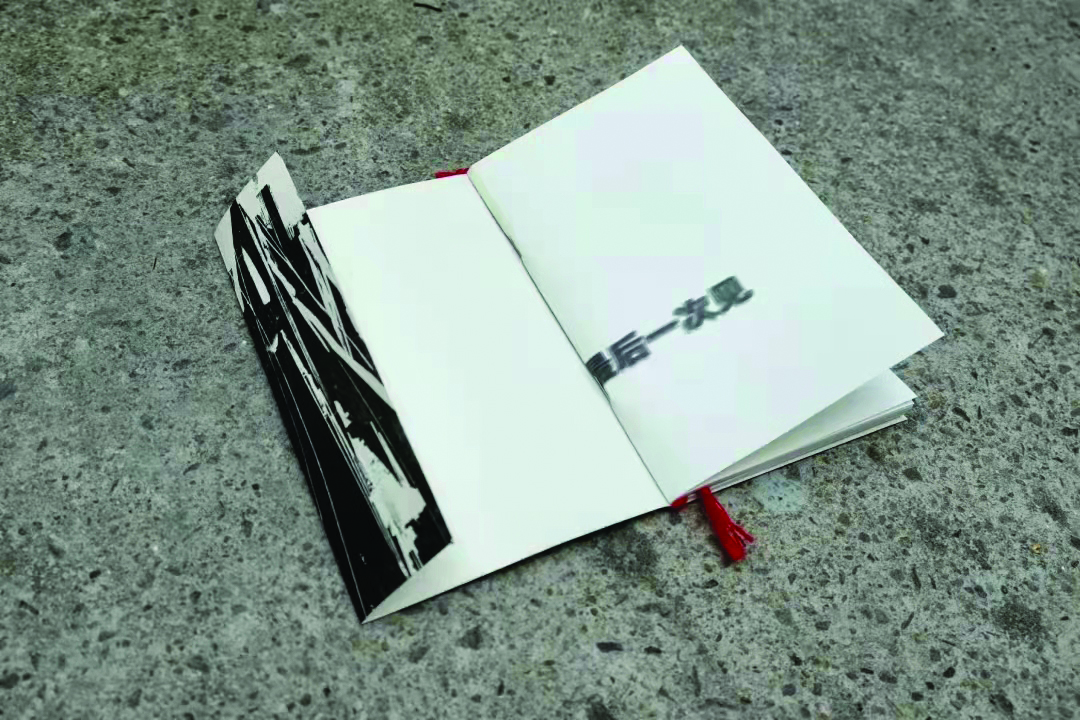

Image courtesy the artist.

During these 11 days, Emma and I began to invite about 40 people to contribute to a writing commission under the title of The Last Time I Saw. We invited them to describe the moment of their last meeting or encounter with Ms. Cheng, either it be two years ago, or two days ago. We selected and edited 26 pieces and finally compiled them into a little book. We arranged them (either poems or essays) in a timeline from earliest to the most recent. The little book also became a witness/expression of an ‘emergency’ moment that went all the way back to two years prior to the moment when Ms. Cheng went missing. The contributors did not necessarily know one another but they share one commonality which is that they knew Ms. Cheng and shared her concern regarding her problem. They were all witnesses of an emergency which they felt did not happen only to Ms. Cheng as the one who was evicted and refused to leave her house, but an emergency that mattered to everyone in our own daily life experience. Memory, if not captured immediately, may go blurry and may never again be more accurately told in a documentary format.

The cover of this book was gifted to us by an anonymous woodcut print researcher and artist. She produced this piece earlier that year and found this work appropriate to serve as the cover of the book. Wild Grass was also the title of a famous prose collection by Lu Xun. The book was ‘published’ a week before Wuhan Lockdown in January 2020. The contributing authors were the first readers of this book, and through this, they became aware of a bigger picture of Jingyun Li event.

Photo by Mira Ying

Since 2018, 51 Personae has been using “Jingyun Li No. 7” as the address of the project, printed on the copyright page of each 51 Personae work. Ms. Cheng never returned to Shanghai since Covid-19 broke out in 2021.

Emergencies, like most human phenomena, repeat themselves. In the case of Jingyun Li, 51 Personae had attempted to tease out and engage with what constitutes a long-term emergency, an emergency that may not look obvious as an emergency to most people most of the time, but is.

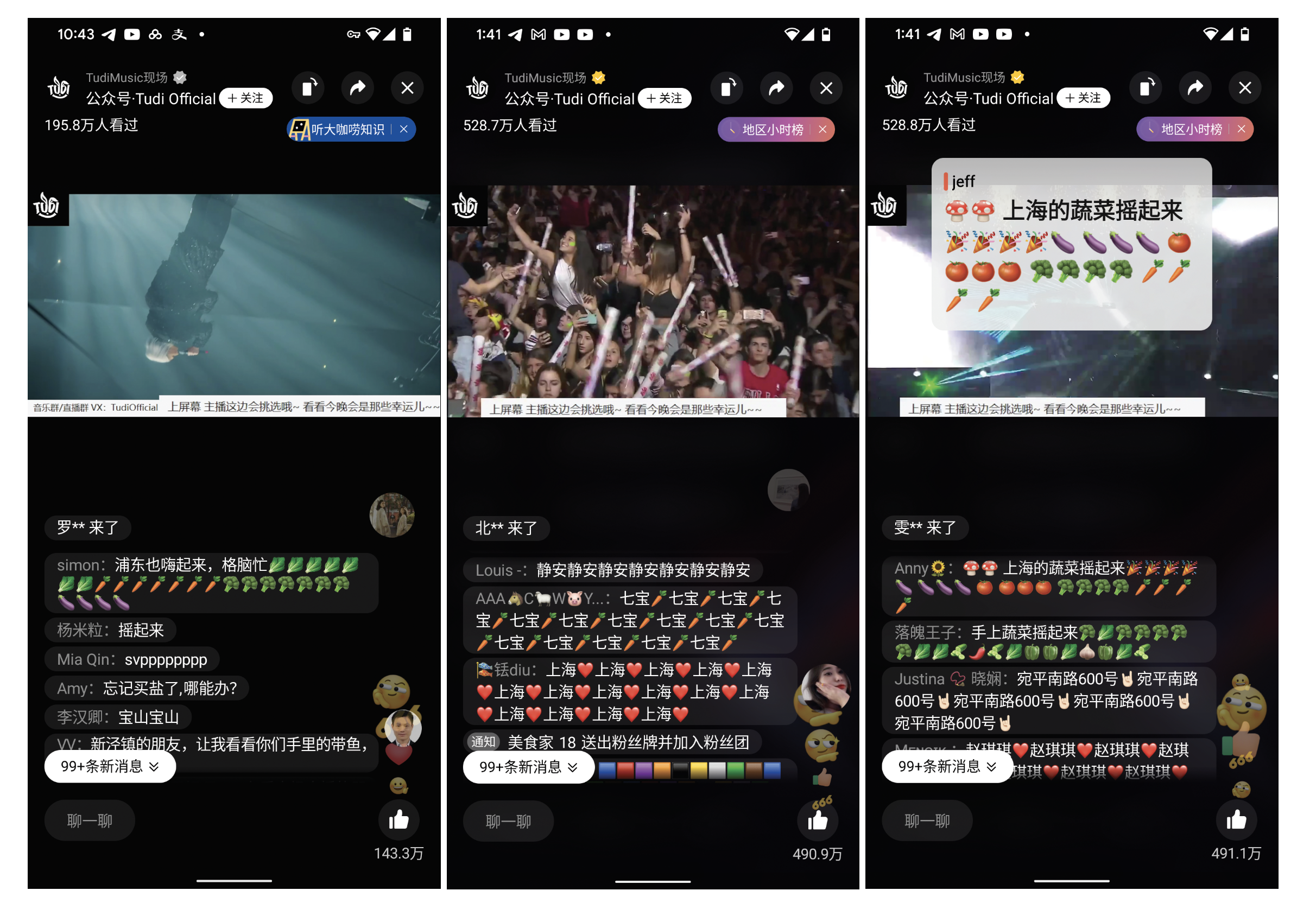

Screenshots by Chen Yun.

An online Spring Festival Gala attracted more than 5 million participants at the night of 31 March 2022. Starting from midnight of 1 April, the West part of Shanghai (Puxi) went officially into lockdown indefinitely. Before that, the East part of Shanghai (Pudong) had been in lockdown for two weeks. Under an ominous cloud, people had rushed to the markets to get whatever foods available at whatever price.

This online Gala was a playback of Ultra Music Festival 2022 at Bayfront Park (March 25-27) in Miami on an electric music wechat video-channel called Tudi Music. Tudi Music did not expect a viewership of a 5-million strong audience, mostly from Shanghai, who participated with passion and spirits no lower than those in Miami, shaking carrots, cabbages and onions in your hands and calling out the names of the neighbourhoods where they are from. This bottom-up celebration of the uncertainty of the Shanghai 2022 Spring Covid lockdown can be seen as a collective activation of an impending state of emergency.

The lockdown following that midnight lasted for an entire two months, when people were not allowed to leave their apartments or their neighbourhoods. Streets were emptied with only vehicles for emergencies and necessities. The city went vacant and the most only obvious sounds heard were from the sirens of ambulances. The cost of this silent spring in Shanghai is still yet to be documented, recognised, and understood—it needs a long-term effort from artists and cultural workers. I have flashbacks of the scene of Ms. Cheng collecting food with a rope-and- basket from the window of her second floor as I write this photo essay. If that was a moment when a personal experience has the power to infiltrate a small part of the public, then likewise we—drawing from our own daily lives—as witnesses as a city of 25 million to this spring of 2022, have the power to open our eyes and hearts to observe the sufferings of others and think about the mechanism behind the ‘emergencies’.

Image courtesy the artist.