The catastrophic shock awakens an acute awareness of the past. It triggers an understanding, albeit belated, of the linear order of events leading up to the calamity. What before was barely legible now reads loud and clear. Yet again, Walter Benjamin’s argument stands—events of the past gain their historical meaning retrospectively.1 And yet, every time such a moment of catastrophic clarity arrives, it comes as a surprise. As if suffering from a peculiar type of collective memory disorder, we are unable to make sense of the past. Long-term memory remains intact, but the recent past is not registered. Unable to produce new memories, we end up living in an endless now. Stuck in an infinite loop, we are doomed to repeat the past, and unable to imagine the future.

Back in the 1980s, Frederic Jameson characterised postmodernism by this very kind of historical amnesia.2 The postmodern subject, claimed Jameson, had lost their sense of linear temporality—the past, present, and future were replaced by a “series of pure and unrelated presents in time.”3 With no cultural forms capable of articulating the present, the endless now starts to resemble a composite in which the present is saturated with the past to the extent that it almost feels right. But it doesn’t feel right. Amid countless catastrophes layering upon one another, the endless now has slowly become an “end times.”4 For only today is guaranteed, never tomorrow—as Günther Anders once put it, speaking of the doctrine of mutually assured destruction.

Our task today is to fight this selective amnesia—to try to remember that the future was once possible. Perhaps it will soon be again. Since with each catastrophe comes the potential for historical rupture, the subversion of the order of things.5 Moments of regression hold a redemptive potential to reveal the contingency of historical order, and to open up space for new social configurations to emerge.

With this potential comes a demand—that the society that created the catastrophe progresses beyond it. And for that to happen, we will need to start remembering, learning, and mourning. We are haunted by the unprocessed trauma of the Soviet catastrophe. In turn, this trauma triggers compulsive repetition: “If the suffering is not remembered, it will be repeated. If the loss is not recognised, it threatens to return.”6

And it is back. We failed to do the work, to remember and to mourn, and today amidst the catastrophe brought on by Putin’s Neo-imperialist regime, we cannot afford to fail again. Only the impulsion to remember can overcome the compulsion to repeat.7

1 On the Concept of History

2 Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

3 Ibid. 27

4 Anders, “End-Times and the End of Time”

5 Diner 9

6 Etkind 16

7 Freud, Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through

References

Anders, Günther. “Endzeit und Zeitende (End-Times and the End of Time),” 1959. Translated excerpt from German by Hunter Bolin. In Apocalypse without Kingdom, in E-flux journal, Issue #97, February 2019, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/97/251199/apocalypse-without-kingdom/

Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Volume 4: 1938-1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 389-400.

Diner, Dan. “Zivilisationsbruch: Denken nach Auschwitz.” Fischer, 1988. Translated in part as The Limits of Reason: Max Horkheimer on Anti-Semitism and Extermination from the book Beyond the Conceivable. California, 2000.

Etkind, Alexander. Warped Mourning: Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied. Stanford University Press, 2013.

Freud, Sigmund. Remembering, Repeating and Working-Through (Further Recommendations on the Technique of Psycho-Analysis II). 1914.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Duke University Press, 1991.

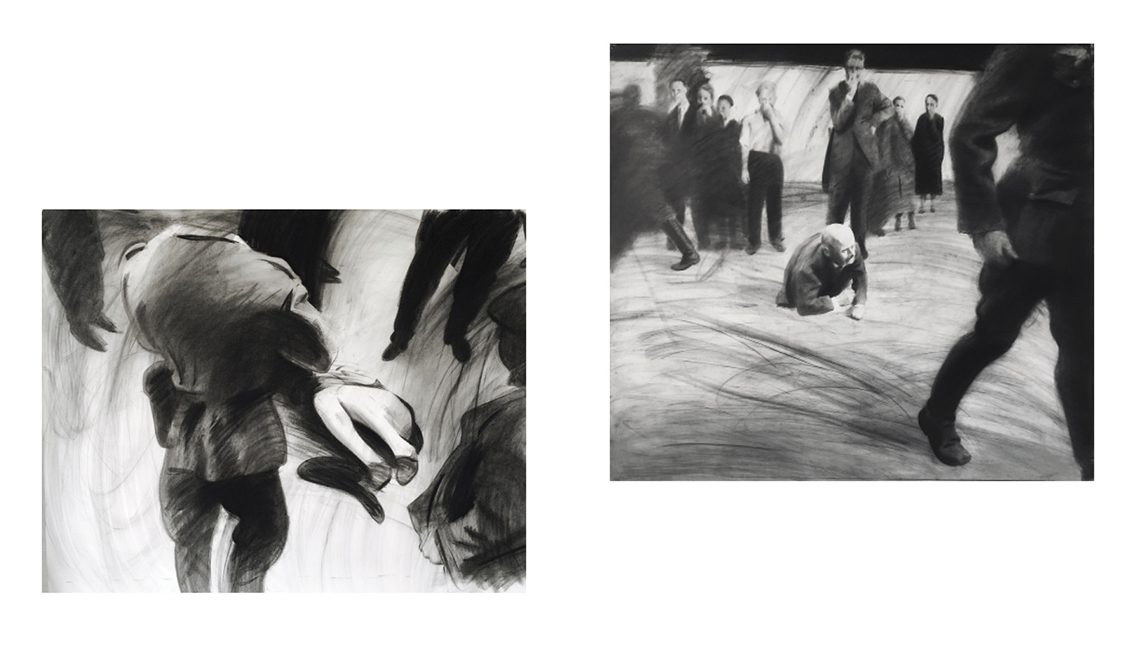

Nikita Kadan

Pogrom

2016–2017

charcoal, wash, paper

Courtesy the artist and Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN – Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie)

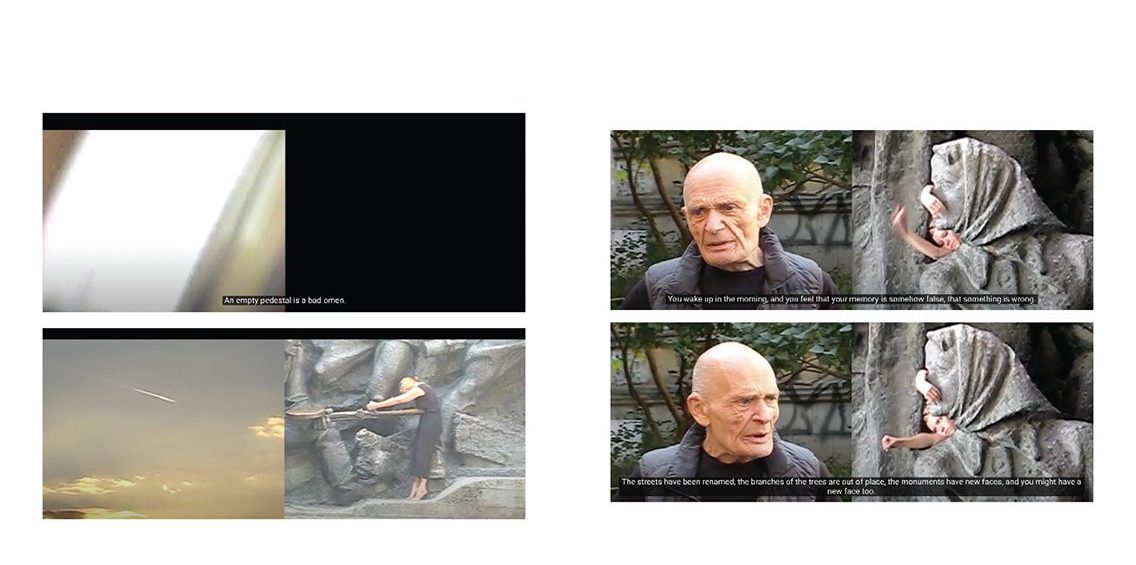

Dana Kavelina

There are no Monuments to Monuments

2021

2-channel video, 34:35min in colour, sound.

Courtesy the artist

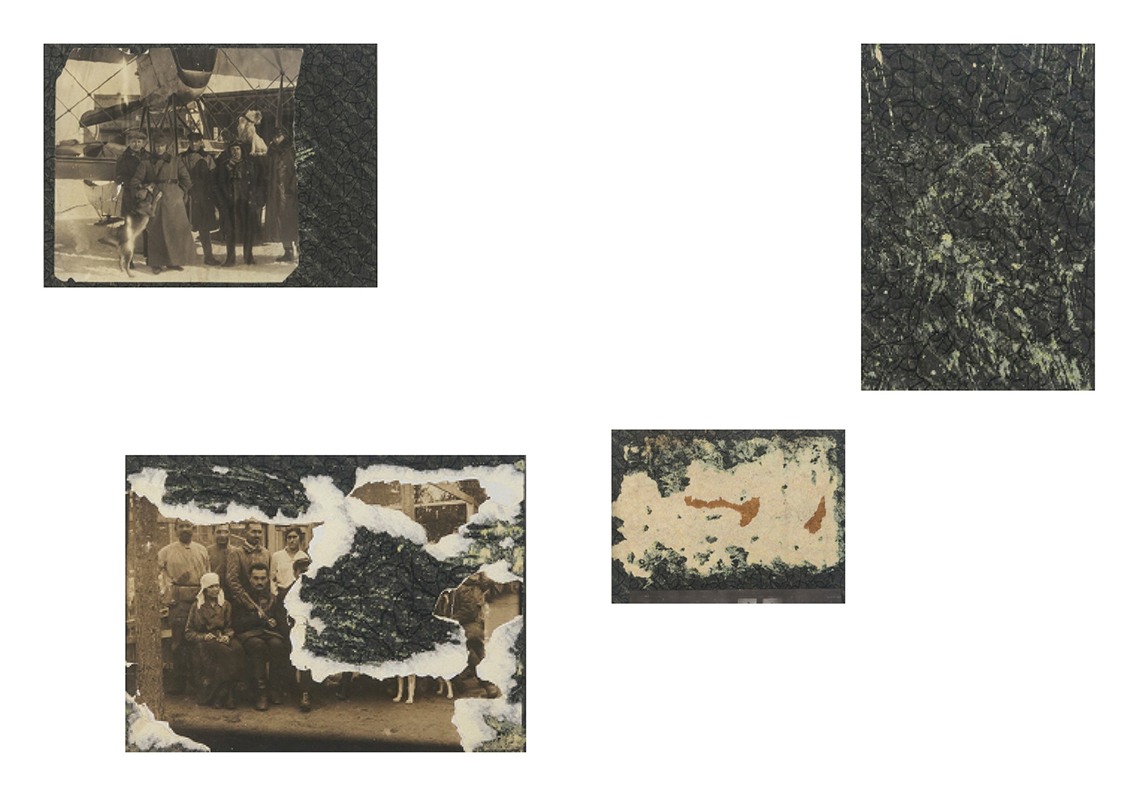

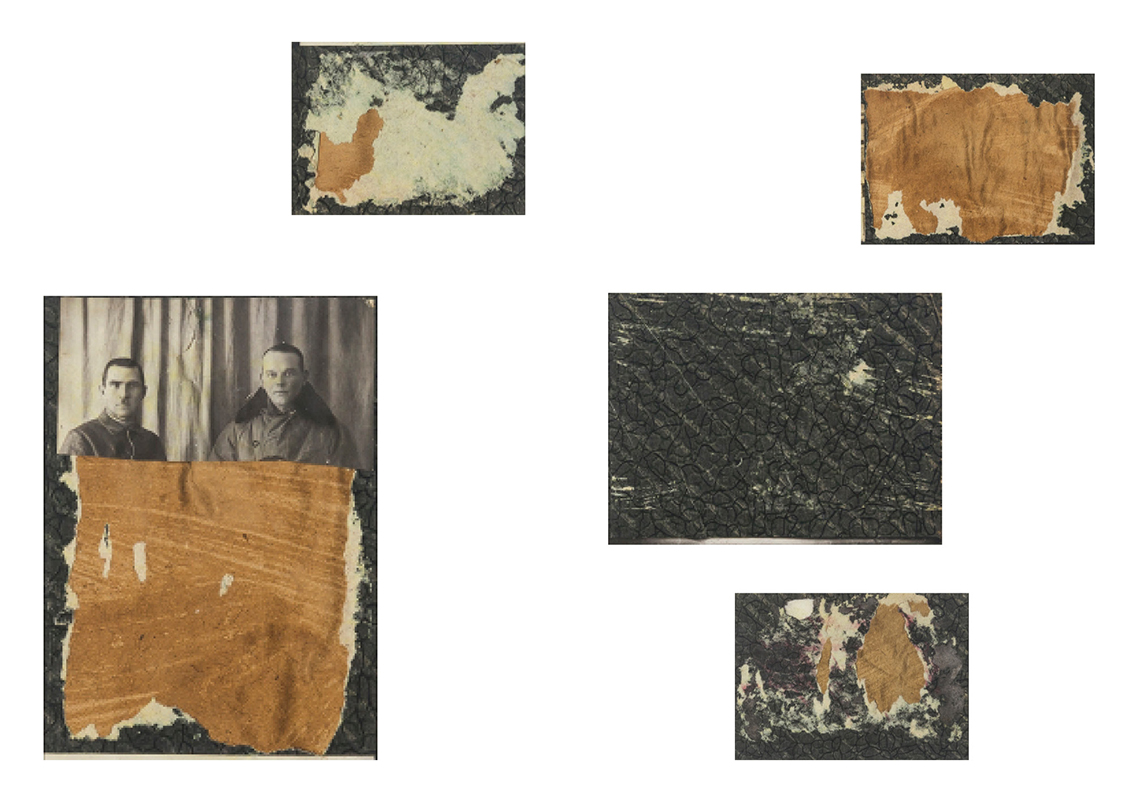

Mikhail Tolmachev

Pact of Silence

2016

22 c-prints

7-channel IR sound-installation

Courtesy the artist

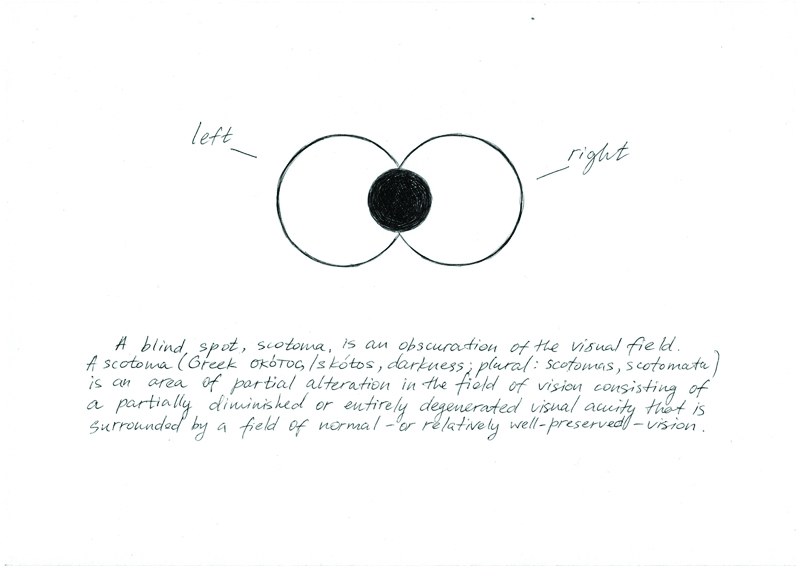

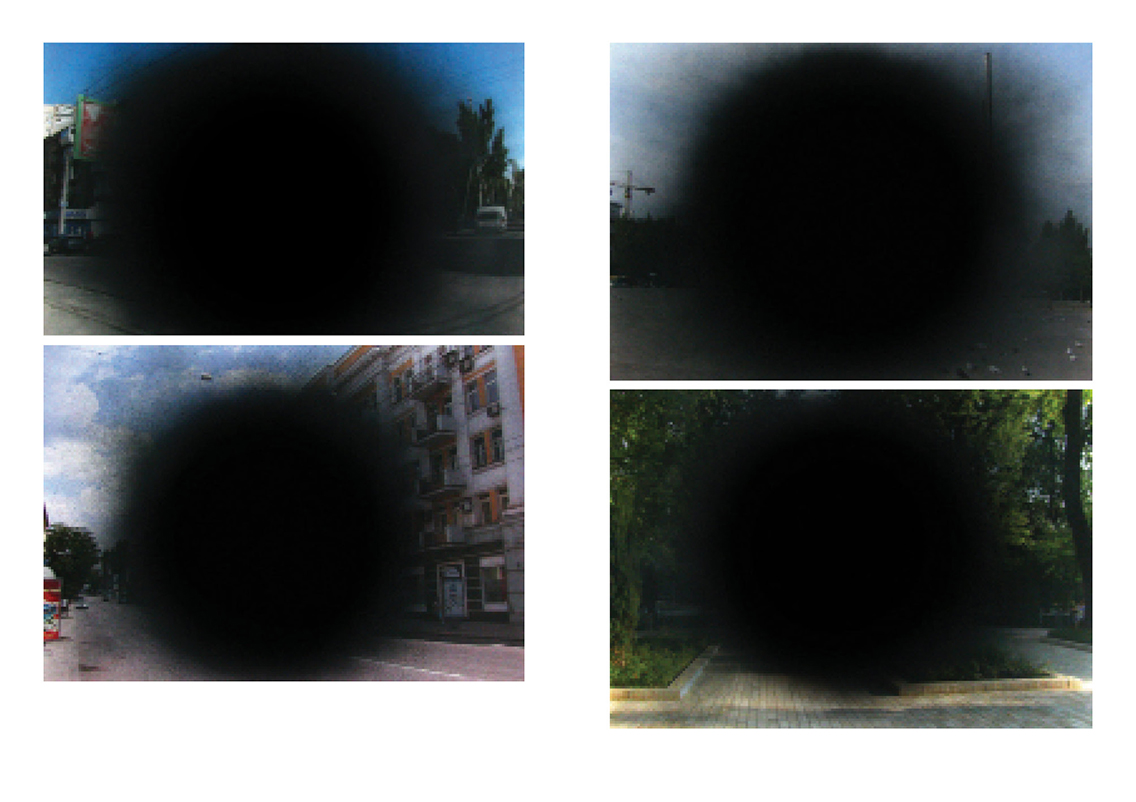

Mykola Ridnyi

Blind Spot

2014–2015

acrylic spray on c-print

42 x 59.4 cm each (8 of a series of 20 works)

pen on paper

21 x 29.7 cm each (2 of a series of 4 drawings)

Courtesy the artist

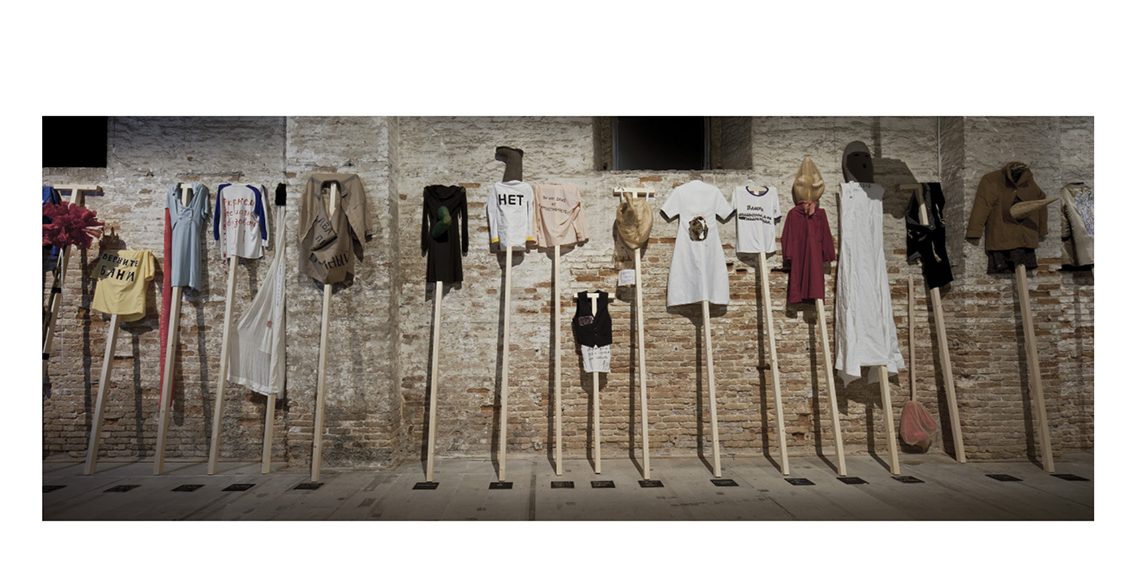

GLUKLYA /Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya

Clothes for the demonstration against false election of Vladimir Putin

2011–2015

textile, handwriting, wood

Courtesy the artist and AKINCI, Amsterdam,

Photo: Alessandra Chemollo; Courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia, with the support of V-A-C Foundation, Moscow

Lesia Khomenko

After the End

2015

A series of watercolours in box-frames under milk glass

Courtesy the artist

In December 2021, amidst yet another wave of political repressions, Russia’s Supreme Court ordered the closure of Memorial International—Russia’s oldest human rights group, founded in the late 1980s to document and study political repressions of the Soviet Union and present-day Russia. The decree was carried out under the “foreign agent” legislation, which indiscriminately targets organisations and individuals seen as critical of the government.

In the fall of 2011, the MediaImpact International Festival of Activist Art took place in Moscow as a special project of the IV Moscow International Biennale of Contemporary Art. The group exhibition, public lectures, and discussions had gathered a great number of local and international artists and activists. Performances and artistic interventions spilled out into the streets and public spaces of Russia’s capital. Just a few months later, the same streets had witnessed some of the biggest protests in Moscow since the 1990s.

I happen to have the catalogue of the MediaImpact festival, which I had conveniently ‘forgotten’ to return after borrowing it in 2013 from the St. Petersburg office of an international arts organisation I was working at at the time, thankfully, amid the frenzy of a “foreign agent” inspection, no one noticed that catalogue had gone missing. Flipping through it now in 2022, as the Russian army is bombing Ukrainian cities, as people in Russia are being arrested for even a slight suspicion of protest activity, to see the documentation of an activist art festival taking place in Moscow feels bizarre, almost unbelievable.

On the following pages are reminders of the recent past, when for a brief moment it felt like another future was possible, and perhaps soon it will be again.

Non-Governmental Control Commission, Vote Against All, 1998

Photograph

Courtesy the artist

Source: http://osmopolis.ru/protiv_vseh/gallery/a_138

Non-Governmental Control Commission, Barricade, 1998

Documentary film (released in 2015)

Courtesy of Russian Art Archive Network (RAAN)

Source: https://russianartarchive.net/en/catalogue/document/V1429

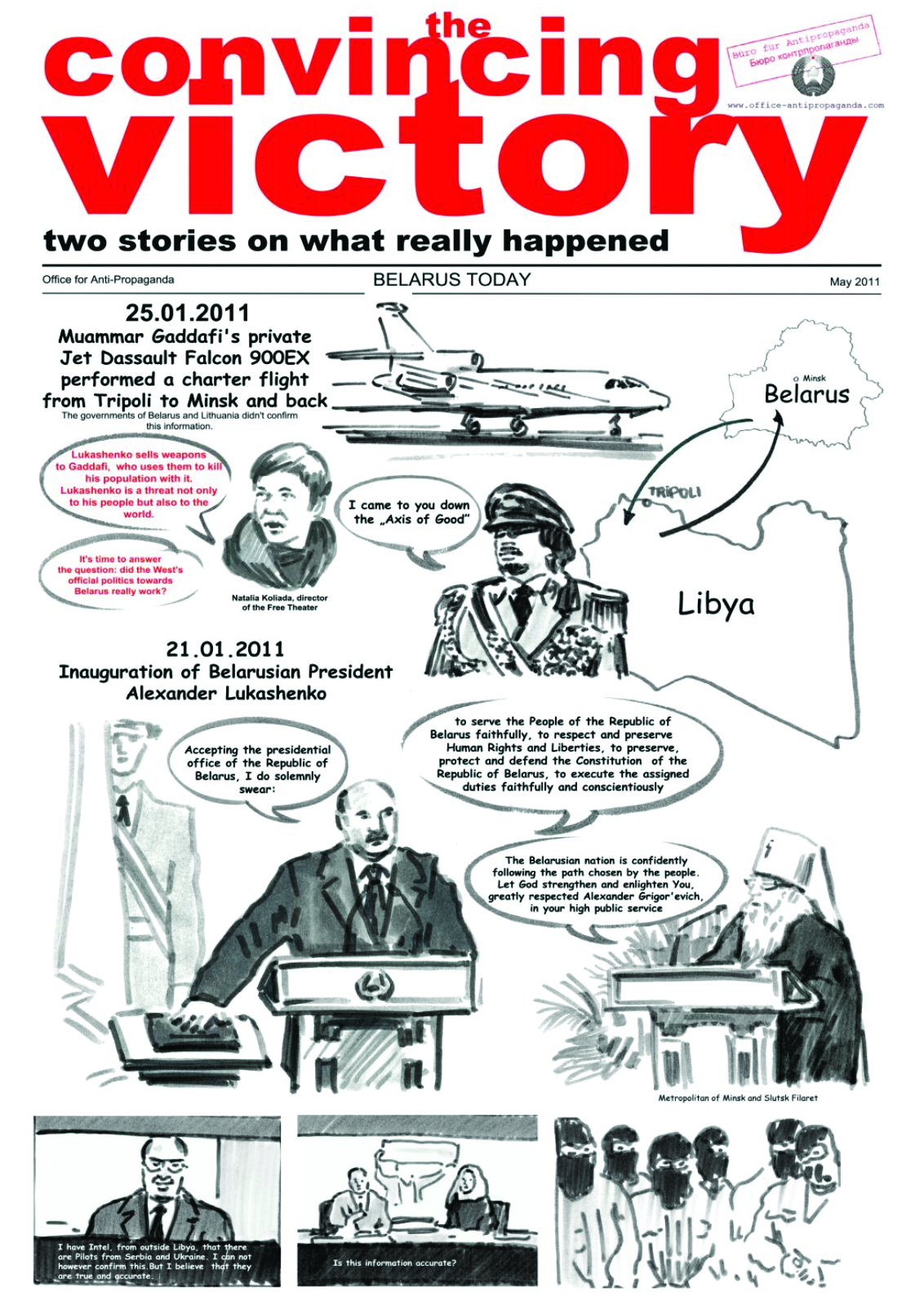

Marina Naprushkina, The Convincing Victory: two stories on what really happened, May 2011

Newspaper

Courtesy the artist

Note:

The 12 pages of the continued political comics illustrate how the situation unwound in Belarus after the

presidential elections in December 2010. All the latest developments—i.e. political repressions, balance-of-

payments and economic crises, a bomb attack in Minsk subway, etc.—are described from two viewpoints: the

first one shows how they are interpreted by the state propaganda machine, the other presents information taken

from independent mass media and blogs.

Oleksandr Volodarsky, Chemistry, 2013

Book

Courtesy the artist

Note:

Chemistry is a collection of writings and drawings that the anarchist Oleksandr Volodarsky kept while serving

time in a penal colony.

Yevgenia Belorusets, Mobilisation, 2012

Video, photographs, text

Courtesy the artist

Source: https://belorusets.com/work/video-mobilisation

Note:

“Whenever I’ve taken part in poorly attended protests, passers-by and accidental spectators have always looked on with undisguised surprise. At some point, it struck me that the demonstration’s subject and goals were meaningless—whether it was about education, labour laws, or brutal violations of human rights.

We invited people enjoying a day off in the centre of Kyiv to take part in a brief improvised protest, which was recorded in stills and on video cameras. The protests were held in advance of legal proceedings to determine the fate of two illegally imprisoned social activist-artists, Dmitry Solopov and Alexander Volodarsky.

Participants were invited to speak out in defense of the two activists, against anti-refugee discrimination, against the violation of prisoners’ rights, or against the criminalisation of political activism and imprisonment for minor offenses. They were offered several banners to choose from; they were also allowed to turn their backs to the camera or hide their faces. For the majority of participants, this was the first protest of their lives. Lots of people refused to take part, while a few of those who agreed only decided to take a stand on the condition that their faces could remain hidden behind the banners. In this case, perhaps the only reliable thing was the banner they held in their hands—like the last bastion, preserving them from the dangers of political life.” Yevgenia Belorusets

Matvei Krylov, You are not Alone, 2011

Cut-out board

Courtesy the artist

Note:

This cut-out board was originally designed for the exhibition Mokhnatkin (Artists supporting Sergey Mokhnatkin) in Sakharov Center. Russian artists had collectively organised a number of exhibitions, happenings, and Internet campaigns in support of the political prisoner Sergey Mokhnatkin who became an accidental victim of a long-lasting political struggle between the authorities and the opposition.

Victoria Lomasko, Chronicles of Resistance, 2011

Ink on paper

Courtesy the artist, Copyright the artist

Note:

“2012 was marked by heavily attended protests by the Russian opposition. For the first time since the early 1990s, the protest movement in Russia attracted worldwide attention. Many people anticipated an “orange” revolution… Beginning with the elections to the State Duma, on 4 December 2011, until November 2012, I kept a graphic ‘chronicle of resistance’ in which I made on-the-spot sketches of all important protest-related events. I will try now to recall and describe the protests, in which I was involved as a rank-and-file albeit regular participant.” Victoria Lomasko

Bombily Group, We don’t know what we want, 2008

Photo documentation of performance

Courtesy of Vlad Chizhenkov archive and Garage Archive Collection

Source: https://russianartarchive.net/en/catalogue/document/F5078

Note:

On May 1 2007—International Labour (Workers) Day, Bombily blocked Bolshaya Polyanka Street in Moscow with a six-metre slogan “We don’t know what we want.” Soon the group was detained by the police, and subsequently, the photo documentation was destroyed The performance was reenacted in the Tushino tunnel and

on Ivanovskoye highway on July 12, 2008. The action was held with the participation of the art group Voina and others.

Pasha 183, True to the Truth 19.08.91 Reminder, 2011

Screenshot documentation by author of life-size stickers of riot police over doors of Moscow metro station.

Source: http://183art.ru/putch/putch.htm

Note:

In True to the Truth 19.08.91 Reminder, the heavy swinging doors of the Krasnye Vorota metro station were covered with life-sized stickers of “OMON”—the Russian riot police. The title alludes to the 1991 Soviet failed coup d’état attempt by hardliners of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party to forcibly seize control of the

country from Mikhail Gorbachev.

Artists’ Bios

Yevgenia Belorusets (b.1980, Ukraine) is a photographer and writer. She is the co-founder of Prostory, a journal for literature, art and politics, and a member of the interdisciplinary curatorial group, HudRada. Her works move at the intersections of art, literature, journalism and social activism, between document and fiction. Her artistic method was established in her long-term projects such as Gogol Street 32, which portrays the residents of a communal apartment building engaged in their daily activities in a slowly decaying living environment. Another is the project Victories of the Defeated which comprised of a series of documentary photographs, texts and interviews, and was dedicated to the coal miner communities which continues to exist in Eastern Ukraine on the very edge of military conflict. To accomplish this work Yevgenia Belorusets visited cities near and in the war zone of Donbas Region in Ukraine between 2014 and 2017.

Bombily Group is an art collective created by the artist and curator Anton Nikolaev in 2004. Members include Anton “Madman” Nikolaev and Alexander “Superhero” Rossikhin, former members of Oleg Kulik’s studio. The name “Bombily” refers to a colloquial name for a private cab driver engaged in illegal taxi services.

GLUKLYA / Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (b. 1969, former Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, Russia) lives and works in St. Petersburg and Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Considered as one of the pioneers of Russian Performance, she co-founded the artist collective The Factory of Found Clothes (FFC) using conceptualised clothes as a tool to build a connection between art and everyday life and the Chto Delat Group, of which she has been an active member since 2003. In 2012, FFC was reformulated into The Utopian Unemployment Union, an inclusive project uniting art, social science, and progressive pedagogy, giving people with all kinds of social backgrounds the opportunity to make art together with the help of artist method embracing the Human Fragility. In 2017, Gluklya passionately threw herself into the research of the Integration Politics and its implications for newcomers, and for this purpose, rented a studio at the former prison Bijlmer Bajes in Amsterdam. The long-term project was concluded with the performative demonstration Carnival of Oppressed Feelings on 28 October, 2017, and presented in Positions #4 at the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven) in 2018-2019. Gluklya’s work Clothes for Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin has been presented at the 56th Venice Biennale of Art (la Biennale di Venezia) in All the World’s Futures, curated by Okwui Enwezor (2015).

Nikita Kadan (b. 1982, Kyiv, Ukraine) is a visual artist and activist who creates paintings, graphic works and installations. His pieces, often developed in collaboration with representatives of other fields (architects, sociologists, human rights activists), address collective memory and historical politics. He is a co-founder of the artistic group R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space), established during the Orange Revolution, and the curatorial-artistic collective HudRada.

Dana Kavelina (b. 1995, Melitopol, Ukraine) is an artist and filmmaker. She graduated from the Department of Graphics at the National Technical University of Ukraine (Kyiv). Her works have been exhibited at the Kmytiv Museum, Closer Art Center (Kyiv), and Sakharov Center (Moscow). She has received awards from the Odesa International Film Festival and KROK International Animated Film Festival.

Lesia Khomenko (b. 1980, Kyiv, Ukraine) is a multidisciplinary artist that reconsiders the role of a painting medium and constructs complex critical statements around it. In her practice, Khomenko deconstructs narrative images and transforms paintings into objects, installations, performances, or videos. Her interest lies in comparing history and myths, revealing tools of visual manipulation. She is co-founder of R.E.P. (Revolutionary Experimental Space) since 2004 and since 2008, a member of the curatorial group HudRada, a self-educational community based on interdisciplinary cooperation. She is a tutor, and a programme director of Contemporary Art at Kyiv Academy of Media Arts.

Matvei Krylov (b .1989 in Orenburg region, Russia) is a political activist and actionist artist. He works with poetry protest evenings and organised dissident traditions like Mayakovsky Readings, as part of his engagement with political issues. He had earned time in Buturskaya Prison, as well as the Alternative Prize of Activist Art.

Victoria Lomasko (b. 1978, Serpukhov, Russia). Drawing on Russian traditions of documentary graphic art, Victoria Lomasko explores contemporary Russian society, particularly the inner workings of the country’s diverse subcultures, such as Russian Orthodox believers, LGBT activists, migrant workers, sex workers, and collective farm workers in the provinces. Her work has appeared in Art in America, The Guardian, GQ and The New Yorker and in exhibitions globally, including at Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna, Austria; Garage Museum, Moscow, Russia; GRAD at Somerset House, London, UK; and the Cartoonmuseum Basel, Switzerland.

Marina Naprushkina (b. 1981, Minsk, Belarus) is a political feminist artist and activist. Her diverse artistic practice includes video, performance, drawings, installation, and text. Her work engages with current political and social issues. Naprushkina works mainly outside of institutional spaces, in cooperation with communities and activist organisations. She focuses on creating new formats, structures, and organisations that are based on the capabilities of self-organisation. In 2007, Naprushkina founded the Office for Anti-Propaganda that concentrates on power structures in nation-states, often making use of nonfiction material such as propaganda issued by governmental institutions. Starting as an archive on political propaganda, the “Office“ drifted to a political platform. In cooperation with activists and cultural makers, Office for Anti-Propaganda launches and supports political campaigns, social projects, publishes underground newspapers.

Non-Governmental Control Commission was founded by Anatoly Osmolovsky in 1989. Anatoly Osmolovsky (b. 1969, Moscow) lives and works in Moscow. He is an artist, theorist, curator, teacher, and one of the founders of Moscow Actionism. From 1990 to 1992, he was leader of the group E.T.A. Movement (Expropriation of the Territory of Art). In 1992, he became editor-in-chief of the journal Radek. In 1993, he formed the group Nezesüdik and In the late 1990s, he created the group Non-Governmental Control Commission. In 2011, he founded the journal Base and the institute of the same name.

Pasha 183 (1983–2013, Moscow) also known as Pavel 183, was a Russian graffiti artist based in Moscow. His work often carried social critically engaged messages over public structures, and he was best known for his grayscale photorealist spray painting.

Mykola Ridnyi (b. 1985, Kharkiv, Ukraine) lives and works in Kyiv, Ukraine. He graduated in 2008 from the National Academy of design and arts in Kharkiv, where he got his MA degree in sculpture studies. Ridnyi combines different artistic activities: he is an artist and filmmaker, curator and author of essays on art and politics. He is a founding member of the SOSka group, an art collective based in Kharkiv in 2005. The same year he co-founded the SOSka gallery-lab, an artist-run-space in an abandoned house in a centre of Kharkiv. Under Ridnyi’s lead, the gallery-lab was instrumental in the developing the artistic scene in the region before it closed in 2012. He curated a number of international exhibitions in Ukraine, among them After the Victory (CCA Yermilov centre, Kharkiv, 2014); New History (Kharkiv museum of art, 2009); and others. Since 2017 Ridnyi is co-editor of Prostory, an online magazine about visual art, literature and society. In 2019 he curated Armed and Dangerous, a multimedia platform that brought together video artists and experimental film directors in Ukraine. Ridnyi works across media ranging from early collective actions in public space to the amalgam of site-specific installations and sculpture, photography and moving image which constitute the current focus of his practice. In recent films he experiments with nonlinear montage, collage of documentary and fiction. His way of reflection social and political reality draws on the contrast between fragility and resilience of individual stories and collective histories. His works are in the permanent public collections of Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, Ludwig Museum in Budapest, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Arsenal City Gallery in Bialystok, V-A-C foundation in Moscow and others.

Mikhail Tolmachev (b.1983, Moscow) is a visual artist who investigates alternative documentary practices. He is looking for aesthetic strategies to explore various constructions of reality and how they form temporality, space and agency. With installations, photo etchings, and spatial interventions he examines the intersections of realism and imagination, technology and territory. Mikhail studied documentary photography in Moscow and Media Arts in the Academy of Visual Arts Leipzig. For his work he extensively collaborates with architects, writers, sound-engineers, poets and historians. Mikhail‘s work was presented internationally, at the Kyiv Biennial, Tate Modern, Moscow Biennial, Moscow Museum of Modern Art, MUSA Vienna and Kunstverein Karlsruhe amongst others. He is based in Moscow and Leipzig.

Oleksandr Volodarsky (b. 1987) is a Ukrainian left-libertarian political activist, publicist, performance artist, and blogger. In the past, he was a member of the independent student union Direct Action, the Autonomous Workers’ Union, and the All-Ukrainian anarchist association called the Libertarian Coordination. He is a programmer by profession. From 2002 to 2009 he studied in Germany and since November 2009 he has lived and worked in Kyiv.