Sam I-shan. Disintegration Loops. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: LASALLE

College of the the Arts, 2019. pp. 107-137.

Page 107

Ivy Ma, Walking Towards, 2012, Pastel, graphite, printed ink on archival paper, 94 x 170 cm

page 108-109

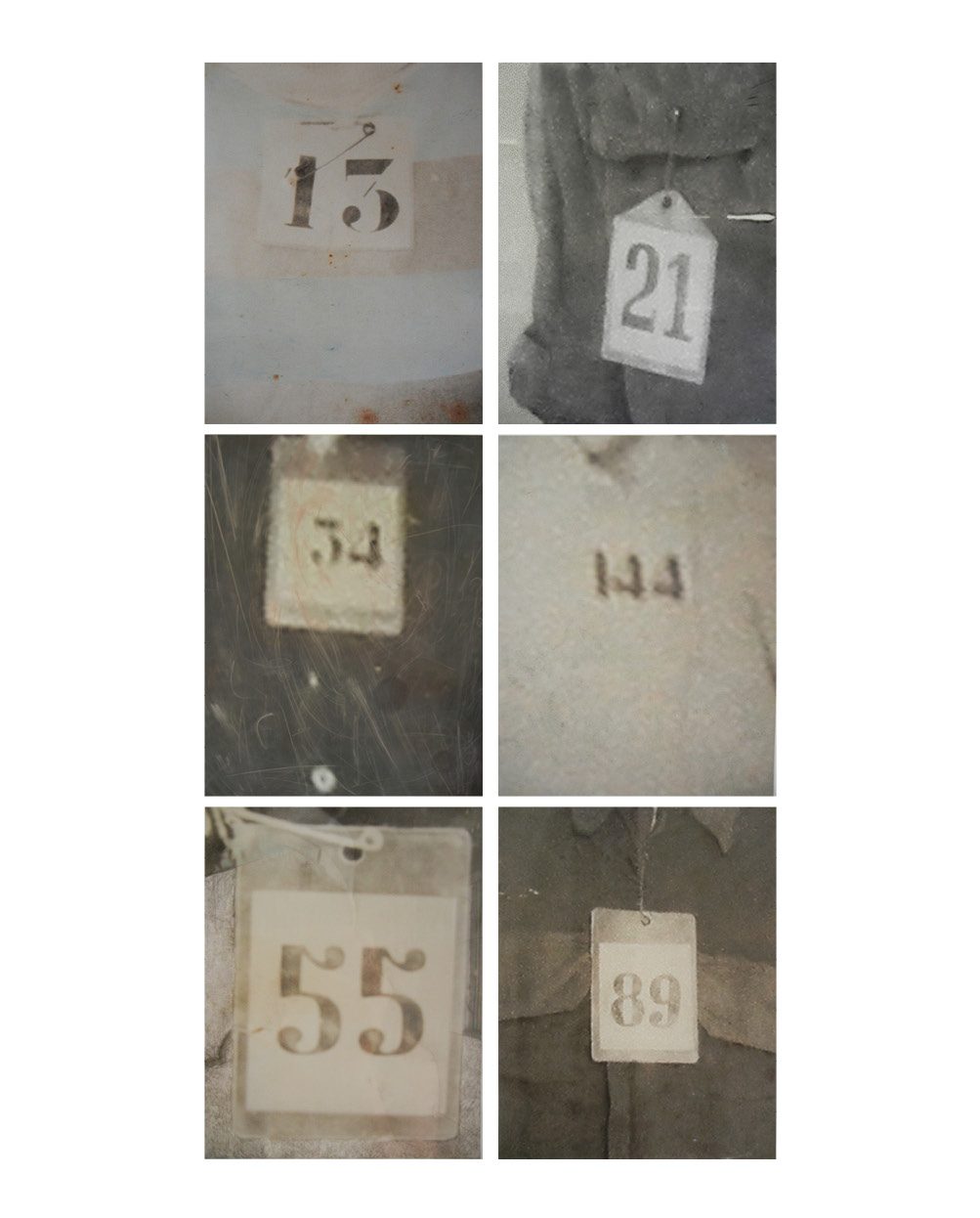

Ivy Ma, Numbers Standing Still, 2012

Pastel, graphite, printed ink on archival paper (set of 11)

78.6 x 60 cm (each)

Ivy Ma, Numbers Standing Still (detail), 2012

Ivy Ma, Numbers Standing Still. Installation view at Hong Kong Museum of Art

Image courtesy of the artist and Hong Kong Museum of Art

Ivy Ma

Numbers Standing Still

2012

Ivy Ma (b. 1973, Hong Kong) works with images from archival and cinematic sources and creates “drawing interventions”—an elaborate process of erasing and drawing into and over existing images. The images she works on are themselves fragmented or indistinct, and possess transient details such as discarded objects or empty spaces. These visual representations and modifications of purposefully “minor” histories that parallel established records, suggest a history of forgotten things that inform and direct our lives as much as any grand narrative. Her work has been exhibited in Hong Kong, Japan, Taiwan and China, and she has participated in artists’ residencies in San Francisco, New York and Helsinki.

The source images of Ivy Ma’s series Numbers Standing Still are from the Security 21 Prison (S-21), formerly the Tuol Seng in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and are based on the photographs that Khmer Rouge cadres took of each prisoner upon their arrival before they were sent on to interrogation, torture, and in almost every case, death. The prison operated from 1976 to 1979, and was methodically run, with every prisoner numbered, and their appearance, measurements and confessions meticulously documented with images and written records. Out of the 15,000 committed to the prison, a mere 14 persons are known to have survived, and the photographs that remain serve as a critical commemoration of the victims of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Ma’s allusion to this grim history is elliptical. She re-photographed selected prints displayed in the prison—now a genocide museum—and strategically cropped them to remove contextual evidence, then used techniques of scraping and mark-making to further obscure their figurative meaning. In particular, her intervention removes one of the striking aspects of the source photographs: the face of the victim. The face is assumed to be indexical to identity and personhood in the same way that causal links are inferred between reality and a photographic image. Instead, her photographs are composed so as to focus on the number tags given to each prisoner, with only the appearance of collars, buttons or a sleeve in the images suggesting that each tag is pinned to or hung somewhere on a person’s upper body. She marked and modified the surface of each image with pastel and graphite, and arranged the selected numbers into the order “1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144.” First described by mathematicians on the Indian subcontinent c. 400 BCE, these numbers have been called the Fibonacci sequence after Italian mathematician Leonardo of Pisa published them in 1202. Each subsequent number in the sequence is the sum of the two preceding it, and this pattern can be read from mathematical models of naturally spiralling forms such as snail shells, flowers and galaxies, and has many applications in art, architecture and music.

Ma’s series delicately posits several simultaneities: it acknowledges the role of photography as powerful visual evidence while alluding to its limits in the revelation of truths; and it is also a double decontextualising, recognising the reality of individual victims, while forestalling the viewer’s ability to voyeuristically view their identities. The question of the viewer’s gaze in relation to these photographs is not an easy one to address. The sheer number of prisoner images in the Tuol Sleng archive, and the way that they have often been presented en masse, whether at the genocide museum, or in other publications or institutional settings, has always been rife with complications. The affective power of these images mean that any display often focusses on their genuinely emotive qualities as visual remnants of atrocity, instead of providing sufficient and proper historical, social or biographical context about the conditions of their production as photographic artefacts.

Ma’s treatment of these source photographs may be read as a head-on tackling of this problem of decontextualising: by removing and obscuring even more visual information than the displays themselves already do, she has abstracted the image down to the barest signifier of this historical moment. The numbers, which were originally assigned by prison authorities as a logistical convenience and to categorically dehumanise the prisoners, take on the moral weight of human tragedy when they are recursively considered, as the sequence that they are presented in implies the sheer number of victims under the abominable practices of the Khmer Rouge regime, and suggests how the single-minded and relentlessly efficient pursuit of a position can result in disaster when taken to its logical extreme. Indeed, while the numbers of those tortured and killed at Tuol Sleng have been well-documented, it is not as widely known that just around a fifth of all those brought to the prison were ordinary citizens, and many of the remaining were Khmer Rouge cadres who were themselves imprisoned and killed when the revolution began to turn in on itself, eliminating through a series of violent purges tens of thousands of its own from all ranks of the army, commune, provincial and governmental administration. By reading the Fibonacci sequence into these genocidal acts, Ma suggests how evil can build upon evil, and exponentially multiply.

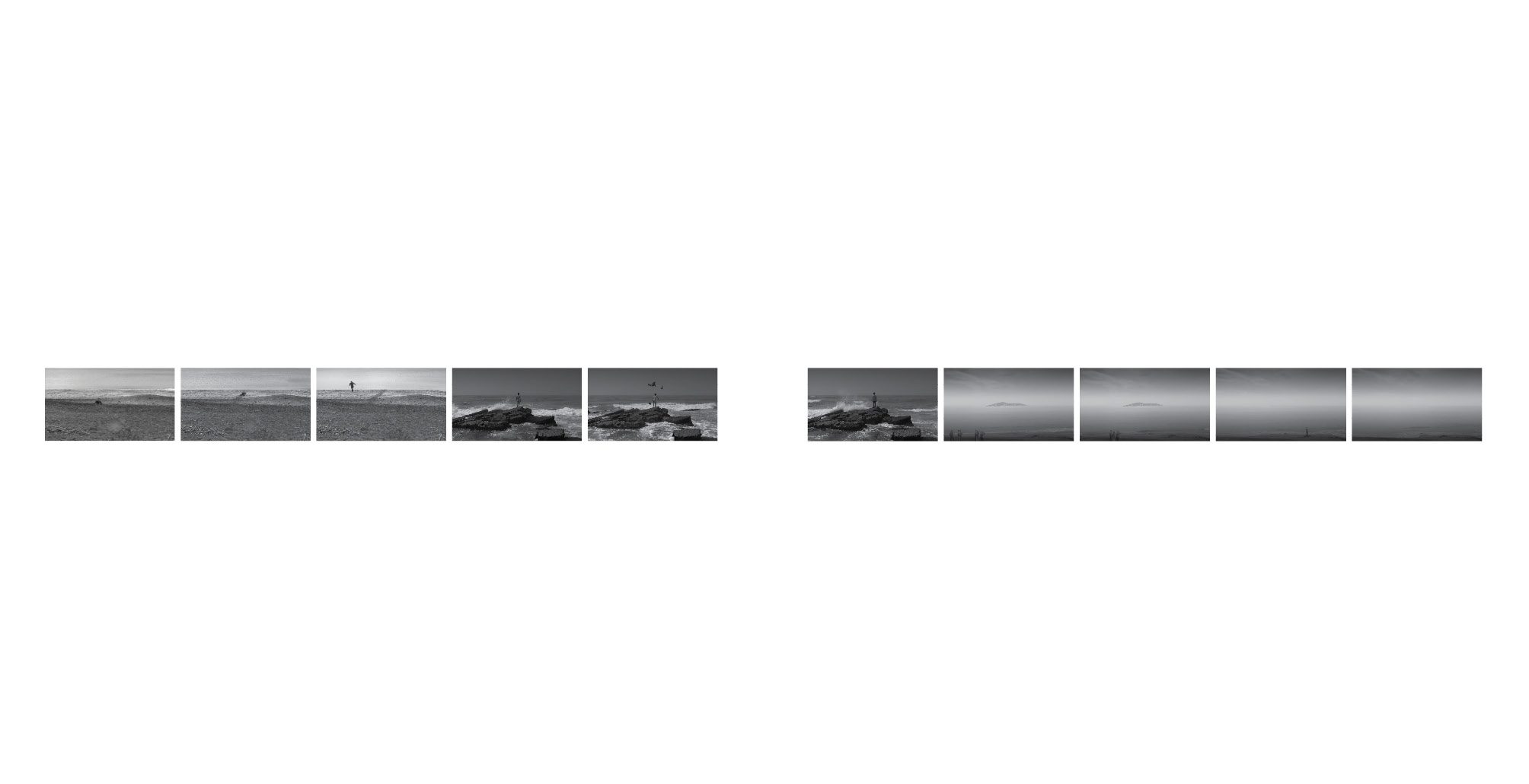

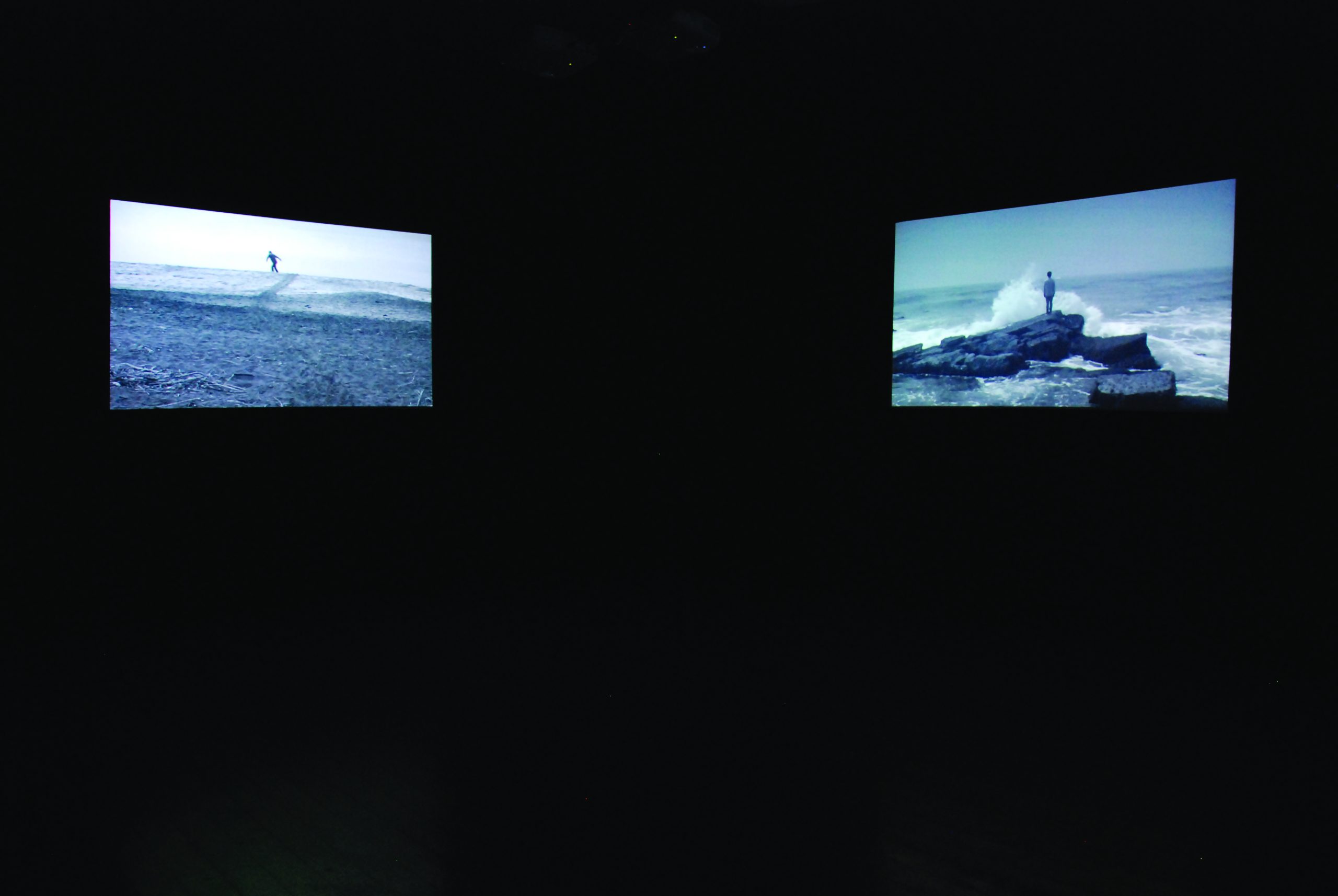

Han Ishu, Form of Sea (detail), 2012

3-channel HD video installation, 5:03 mins, black and white, sound

Images courtesy of the artist

Han Ishu, Form of Sea. Installation view at Kyoto Art Centre

Image courtesy of the artist and Kyoto Art Centre

Han Ishu, Form of Sea. Installation view at Japan Media Arts Festival

Image courtesy of the artist

Han Ishu

Form of Sea

2012

Han Ishu (b. 1987, Shanghai, China) lives and works in Tokyo, Japan. His films, video installations, performances and photography raise questions of national and territorial identities, and explore the contingent role of cultural and popular iconography in socio-political contexts. His works have been featured in solo exhibitions in URANO Gallery, Tokyo, MoCA Pavilion, Shanghai, Koganecho Site-A Gallery, Yokohama, and in multiple group exhibitions in Japan, the U.S., U.K., Hong Kong, Taiwan and Southeast Asia. He has participated in artist residencies with the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, International Studio and Curatorial Program New York, and Tokyo Wonder Site, and is a recipient of the Asia Cultural Council Grant, amongst other awards.

Han Ishu has always been connected to port cities: he was born in Shanghai, China, raised in Aomori, Japan, and lives and works in Tokyo. Shanghai’s historical and present-day economic and cultural importance is tied to its status as major trading port and cosmopolitan costal metropolis. Meanwhile, Aomori is the northernmost capital city on the main island of Japan and a major fishing port since the Edo period. The precursor to the current Port of Tokyo, the Edo Port, was one of five opened to foreigners following the signing of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States in 1858, which formed the basis for Western economic penetration of Japan and heralded a raft of commercial agreements widely referred to by the Japanese as an “unequal treaty system.” The notion of social identities emerges frequently in Han’s work, and is often explored through the trope of the ocean, particularly in relation to indeterminate, inconstant and contested borders and territories.

Form of Sea is a three-channel work that combines and builds upon three videos that have, in common, a horizon or landscape line that splits the screen, with tiny human figures or terrain relating performatively to the sea. In one of the videos, the artist is shown crawling toward the ocean and remaining in the surf for a while before getting up and running back toward the beach. He endlessly tries to occupy the water but is always forced to retreat back to the land. The grey, grainy totality of each half of the sand and sea mean that the distinction between them is demonstrated primarily by the movement of the figure in relation to the physical line that demarcates them, that is itself always changing as the ebb and flow of the waves sculpt and change the shore.

In the other two videos, the sea fills most of the screen, with the horizon dividing it. One of these works documents a performance by Han, who stands on a rock outcrop and proceeds to remove all his clothing, flinging each piece into the sea. However, the video is shown in reverse, so the clothes seem to return to his body, even as the waves dramatically recede rather than crashing onto the shore. This work was made after the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 devastated the Tohoku region (where Aomori is situated), killing more than 20,000 and triggering a nuclear disaster that caused massive damage and destruction. The repeatedly retreating waves in this work appear almost like a poetic counterpoint to the terrifying tsunami that swept away so much, expressing the hopeless but very human wish to avert disaster by representing its reversal.

In the third video, an island floats on the horizon and slowly sinks into the sea as small figures, who appear to be sightseers, watch and take photographs from the shore. Han made this work by filming the seascape and combining it with a three-dimensional rendering of one of the five land masses that make up the Senkaku Islands, which he found on a satellite map. Located in the East China Sea, and equidistant between Japan and Taiwan, they are called Senkaku by the Japanese, Diaoyudao by the Chinese and Diaoyutai by the Taiwanese. With a total area of about seven square kilometres, these uninhabited islands are the site of long-standing territorial disputes between the three countries. Their respective claims are based on varying frames of reference, including older accounts of voyages and discoveries, annals and maps, as well as utilitarian evidence such as land surveys, population registers and treaties. Critical ostensibly because of their proximity to key maritime routes, fishing grounds and possible oil reserves, the islands’ strategic location also means that they would be valuable for any country with ambitions to compete with the United States for military primacy in the Asia-Pacific region. Regardless of the true or perceived value of these islands, governments have also historically made claims of territorial sovereignty so as to signal political priorities to a domestic audience and advance their strategic agendas regionally and internationally. The subtle appearance and disappearance of the island in the video, its inaccessibility underscored by the remote observing human figures, implicitly points at these political sleights of hand, and bring these abstract conflicts back to the materiality of land in a melancholic, muted way.

Page 120 – 125

Taiki Sakpisit, Trouble in Paradise (film stills), 2017

HD digital video, sound, colour. Duration: 13:00 mins

Images courtesy of the artist

Taiki Sakpisit

Trouble in Paradise

2017

Taiki Sakpisit (b.1975, Japan) lives and works in Bangkok, Thailand. His experimental films and moving image installations explore sites, spaces and moments haunted by personal and historical memory, and feature complex soundscapes made in collaboration with sound designers. With its dense iconographic lexicon, his work often makes elliptical references to the myths and socio-political climate of contemporary Thailand. He has had several solo exhibitions, the most recent at S.A.C. Subhashok The Arts Centre, and his film projects have been shown and awarded at numerous international film festivals.

Taiki Sakpisit’s film works are haunting assemblages with non-linear, sometimes enigmatic narrative structures. His striking images, which are often montaged in extended takes, slow motion and layered dissolves, are accompanied by non-diegetic soundscapes composed by the sound artists he collaborates with. Otherwise, his process of conceiving his films and sourcing archival material, to shooting on location and editing, is primarily a solitary one. The result is a highly personal and densely interwoven universe of visual iconography, formal techniques and aesthetic choices, from which themes related to Thailand’s history, society, religion and politics can be read.

The opening intertitles of Trouble in Paradise1 refer to “being and nothingness, absolute nothingness,” and “the city of no concern, the city of nirvana.” A key aspect of Buddhism is the doctrine of “non-self,” namely the absence of an unchanging soul or essence in every living entity. Nirvana is a state where true emptiness is fully realised; what is understood as conventional reality disappears into this “absolute nothingness.” This textual preamble is followed by the first of several recurring images of tunnel- or path-like spaces in the work. A channel of rock leads into a shadowed cave, seeming to invite the viewer to leave the world of perceivable fact and enter a place of uncertainty where anything might be discovered.

The first of five sections then follows: Summer depicts an anonymous-looking interior corridor with yellow-tinged walls lit by fluorescent light. The season of summer suggests a time of warmth and natural largesse, or youth and fruition, but the artificially-lit stillness and receding shadows of the corridor setting, lined by closed doors that harbour unknown spaces, suggests a man-made foreboding instead. The next section, A Ball, features blue and green points of light that dance across the frame. The camera also catches the flicker of another kind of light that could be a candle flame, or the edge of an eye, or a hand cupping the lens, a presence that is almost always just out of focus. The lights then increase in frequency and distance, changing their scale and intensity to appear like headlights or strobe lights in a distant landscape. The scene then shifts abruptly to one of a forest in broad daylight. This third section, Paradise, shows a buffalo standing in the middle of a narrow clearing formed by a receding line of trees. The images fade to show two or three more of these silent beasts as the soundtrack swells and rises, becoming more urgent, and almost siren-like. The next section, Earth, shows sai sin, or white sacred threads, tied in a grid pattern, looped around a person’s head, or wound around their fingers. During temple ceremonies, these threads link the monks and statues of the Buddha to devotees, with associated merit symbolically passed along the thread from them toward all the people in the temple. When the thread is unbroken or circular, the connection is believed to be more powerful because the circle is continuous. Other devices associated with temple worship, including an image of a monk, pieces of gold leaf, a candle flame and incense are layered atop each other, and gradually dissolve as what appears to be branching veins grow and spread across the monk’s face. However, this is soon revealed to be a leafless tree growing out of a lake and silhouetted against a dark mountain and grey sky, which is also the last chapter in the film, Earth Again, before the screen fades to black.

The hypnotic, droning soundtrack to these images does much to create a dream-like atmosphere, and the way that the sequences build up throughout the film initially suggest a kind of ascension through various pathways toward a condition of idyll, where everything appears to be as it should. Intimations of circularity—from the white sacred threads, or doubled reflections within the frame, or images of water that appear at the beginning and end of the film, appear to describe the kind of equilibrium typically associated with Buddhist world views. However, the unease that lurks within the images, particularly in the way they dissolve into and follow one another, suggest that this state could be one of unresolved limbo rather than harmonious balance. The “trouble” described in the film’s title, and the double presence of “earth” and “earth again,” suggest that the usual process of birth, aging, death, rebirth, and redeath in the cycle of existence has been somehow ruptured, and things are not as they are or could be. The beauty and power of Taiki’s work lies in the oracular possibilities that arise from its rhythmic and intuitive juxtapositions of image and sound. The qualities of disquiet and awe that this creates, and the imaginative associations that are sparked might equally evoke the turbulent cycle of protests, elections and coups that has marked decades of Thai politics, or simply indicate the horror of a cosmos gone awry.

Page 128 – 131

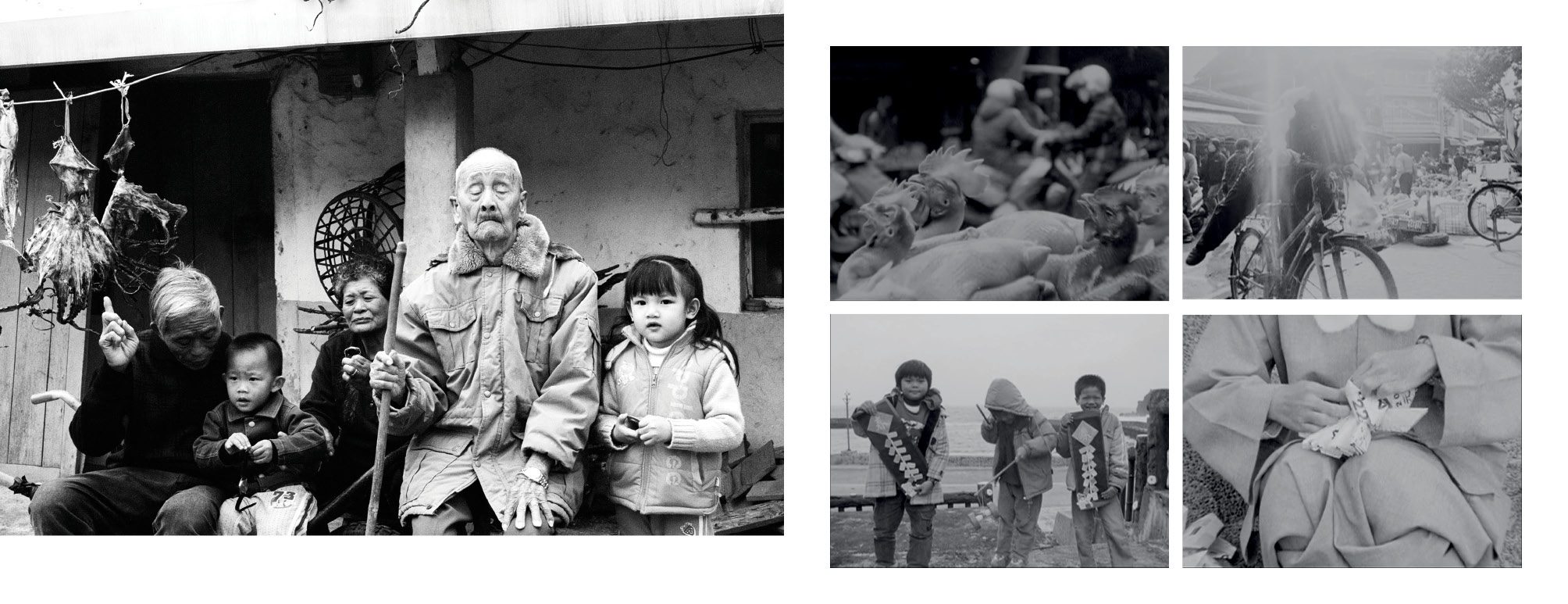

Ye Mimi, They Are There But I Am Not (film stills), 2009

16m film transferred to digital, sound, black and white

Duration: 6:55 mins

Images courtesy of the artist

They Are There But I Am Not

Written by Ye Mimi

Translated by Steve Bradbury

A watch is there but time is not

Time is there but people are not

People are there but chickens are not

A parrot is there but God is not

Three o’clock is there but nine o’clock is not

Spring is there but winter is not

A calendar is there but the numerals are not

My right eye is in today

But my left eye is still in yesterday

My left knee is in the day after tomorrow

But my right knee is arriving at the year after next

Was this 500 year-old ocean touched by 500 year-old hands?

Or were these 500 year-old hands touched by the 500-year old ocean?

They break time with their feet

And then pretend they’re out in space

Time isn’t there but it is

They are there but I am not

Time isn’t there but it is

They are there but I am not

Before before is behind

Behind behind is before

As the oldest person turns back

She becomes the youngest

As the youngest person turns back

She becomes the oldest

Time isn’t there but it is

They are there but I am not

Time isn’t there but it is

They are there but I am not

Ye Mimi

They Are There But I Am Not

2009

Ye Mimi (b. 1980, Taiwan) is a poet and filmmaker. A graduate of the MFA Creative Writing Department at National Dong Hwa University, Taiwan and the MFA Film Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she is the author of three volumes of poetry. Working with both digital and celluloid film, she makes poetry films that improvise new landscapes and scenarios through a collage of words, images, performances and interactions. Her work has been shown at Taiwan Contemporary Culture Lab, Museum of Contemporary Art Taipei, and international film festivals and poetry festivals in New York, Berlin, Rotterdam, Cairo and others. Her books have been translated into English and Dutch.

Ye Mimi makes what she calls poetry films, reflecting how her art practice is rooted equally in text and image. In They are There But I Am Not,2 Ye delivers the lines of the titular poem in an intimate, whispering voiceover, juxtaposed with images primarily shot in Green Island and other places in southwest Taiwan including Chiayi and Liuying. Taiwan’s southern regions, where the country’s oldest city and former capital Tanian are located, are rich with history, folk tradition, and architectural and cultural remnants from Dutch and Japanese colonial rule. Green Island, located off the country’s south-eastern coast, is known in more recent times for being the site of a penal colony and re-education camp for political prisoners during the White Terror, Taiwan’s period of martial law from 1949 to 1987.

These complex histories, however, are not overtly foregrounded in the work, with place and site hinted at instead by the specificity of local produce and religious custom, or scenes set on the island’s coast. A rotating cast of island residents, including students, a tai chi group, a spring roll hawker, longan factory workers, a Buddhist nun, a god, a parrot, and chickens, among other credited players, appear performing their daily employment activities and routines, working with their hands, making meals, or going to the market. Some are also shown interacting with various kinds of timekeeping devices: presenting clocks to each other and occasionally toward the camera, or playing games such as passing around balloons on which clock faces are drawn, then stamping them into shreds.

These gestures and actions suggest various ways of experiencing the passage of time: post-capitalists might define it as gainful labour alternating with permitted moments of leisure, but time is also a thing that has the potential to be relative, contingent and playfully overturned.

Rather than the interminable forward march of historical events, the film posits a broader, more philosophical take on temporality that speculates about the various shapes time can take, ranging from the circular to the fragmented, and the visible to the absent. The poem uses antithesis within each line and across the verses to suggest that divergent elements can complement as well as oppose. The accompanying images add another layer, at times undercutting, and at other times substantiating Ye’s utterances, which further disorder the narrative causality of sound and image. By the end of the poetry film, the pronouns “they” and “I” of the title and the refrain shift in meaning to irreverently negate any universalist claims to knowledge and ideologies of progress.

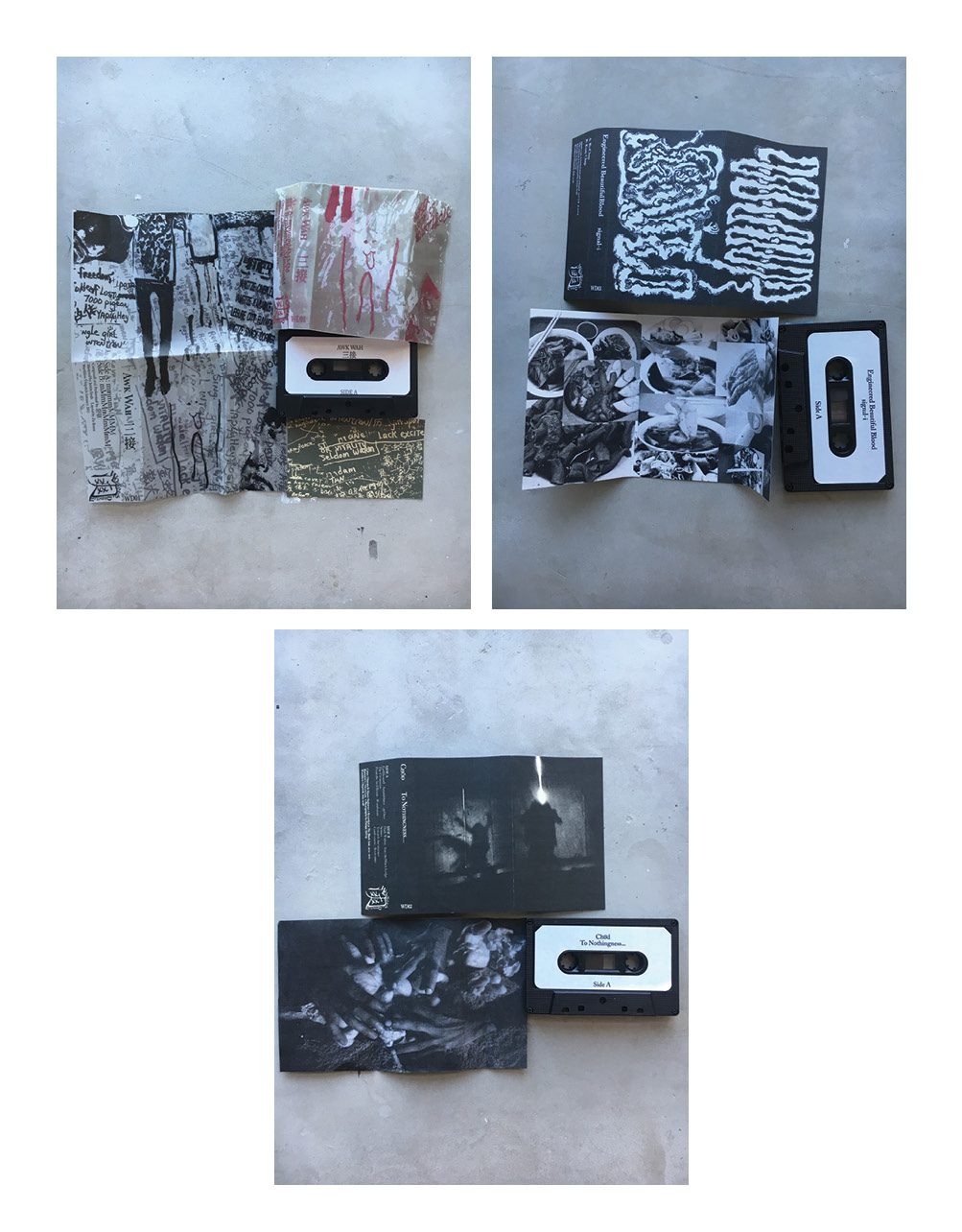

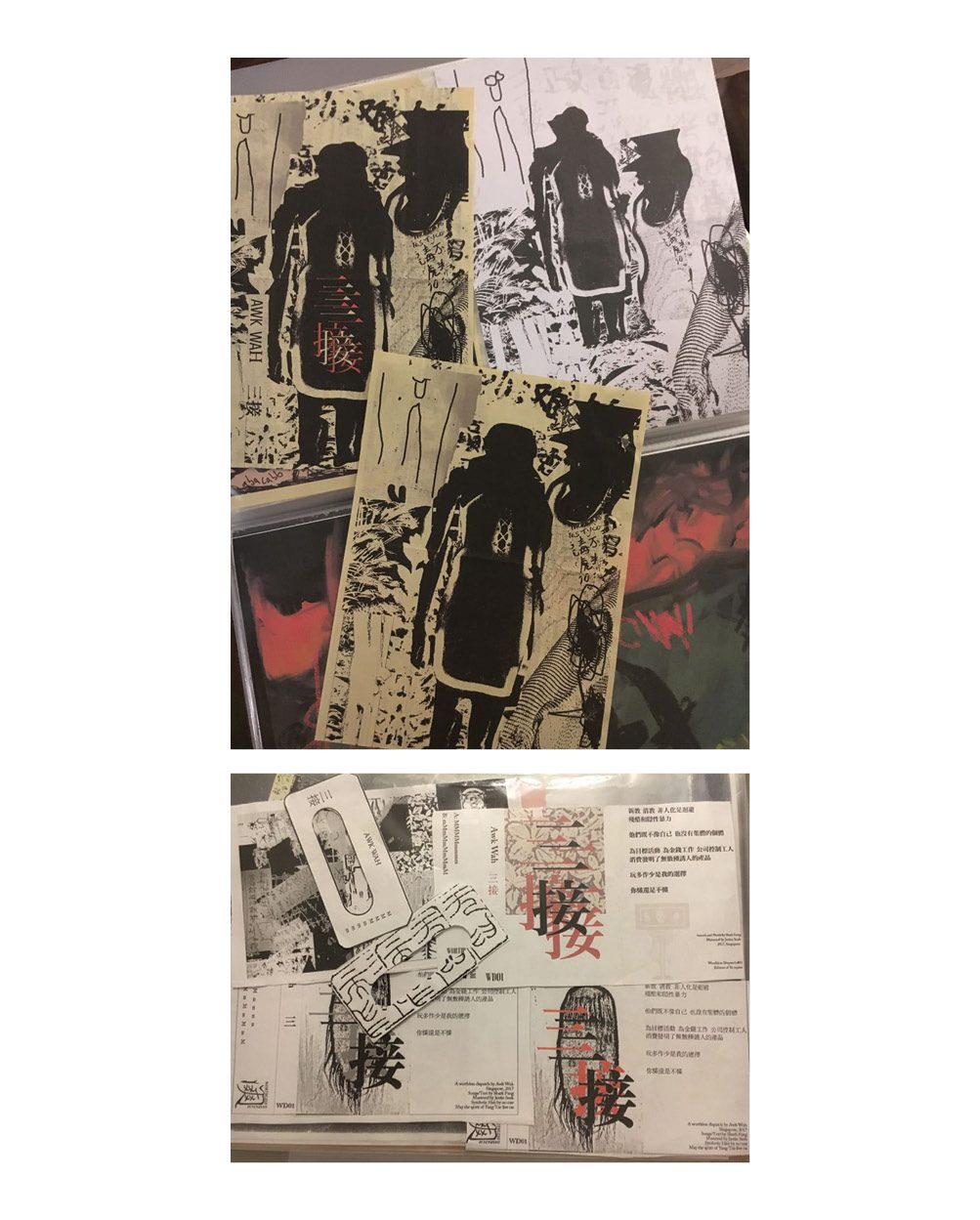

Releases from Low Zu Boon’s Worthless Dispatch cassette label

Low Zu Boon/Worthless Dispatch

Design prototype for 01, AWK WAH, 三接, 2018

Low Zu Boon

Worthless Dispatch

Low Zu Boon (b. 1984, Singapore) loves to watch, write and present cinema, and remains severely indebted to the medium’s possibilities. He worked as a film programmer at the National Museum of Singapore Cinematheque (2011-2015) and the Singapore International Film Festival (2015-2018). In 2018, he started Worthless Dispatch, a cassette tape label with a limited run, and is currently working with The Observatory as their company manager.

This conversation arose out of a discussion about making and exhibiting film and music with analogue formats. Photochemical film and magnetic tape are considered relatively stable media, if produced and preserved in the right archival conditions. As with many analogue systems, the primary conservation question is to prevent the degradation of material data, as opposed to the problems of technological obsolescence and compatibility that arise from the use of digital.

The prevalence of photographing on film, shooting on celluloid, and reproducing music on vinyl or magnetic tape has risen and fallen with changes in technology and demand, but the last few years have seen a quiet resurgence of interest in rediscovering these formats. Digital recording technology is associated with technical sophistication, complexity and control, while analogue is associated with warmth, texture and authenticity. However, the reality is that music is more often than not made and disseminated with a combination of analogue and digital techniques. The evolution of these forms and formats reflect the circumstantial peculiarities of the ways that music can be created and consumed.

Low Zu Boon as told to Sam I-shan

(12 April 2019, Singapore)

Underground tape culture began in the late 1970s and early 1980s when musicians would release their music on cassettes through a system of mail order or trade, postal deliveries and magazine advertisements. It’s still operating healthily—and stealthily—in the present, but in combination with different audio media and communication channels. It can be quite surprising that nostalgia isn’t always involved when listening to and working with tape as a medium. I actually got into collecting tapes simply because I didn’t have other ways of accessing music I was interested in, especially certain kinds of experimental or electronic music.

The first cassette I got was by an Italian artist, Maurizio Bianchi, from Mirror Tapes, a Kuala Lumpur-based publisher and distributor of experimental music active between 2010 to 2011. I typically search for hard-to-find music on Discogs, a comprehensive database where you can also buy and sell records. I’ve also been looking for music that I have always heard about but never listened to in person, especially industrial genres that have not been profiled much in compilations of Singapore music. I also happen upon finds: for instance, I recently acquired cassettes from the collection of Philip Cheah, co-founder of BigO magazine, because I was looking for some works by Nunsex, a band with roots in thrash metal, punk and industrial noise. BigO was critical for the development of the independent music scene in the 1980s and 1990s and many musicians and bands sent tapes to them.

I started Worthless Dispatch as a way to work together with some musicians that I admire. One of the reasons why I release on tape is that it is the most inexpensive media to duplicate. Vinyl is costly to produce, and the CD is a format that no longer sells well. The cassette as a form of physical media is affordable but still seen as a collectible by people who want something analogue. Personally, I am indifferent about digital distribution and there is no virtue to giving easy access to materials online. Everything works well on a tape unless one wants a very precise kind of tonal quality, but the kind of music I release and listen to myself doesn’t require that. In fact, the clarity of a CD can be jarring because it is the equivalent of watching something on a LCD screen. The way that music is recorded on a tape is enough for any kind of listening.

I began with Awk Wah3 because I heard a particular performance by him at Melantun Records, a temporary installation and performance space in Far East Plaza organised by Ujikaji for State of Motion 2017. There was no fixed schedule so he just played on and on, mumbling softly in Chinese. It felt different from his usual more abrasive work, and I was curious about this direction, so I asked him if he wanted to work on something, and we ended up with the first release, 三接. It’s a record that has the quality of a sketch, with each side one enunciation. After that was Chöd’s4 To Nothingness, a collaboration between Dharma and Shaun Sankaran based on jam session recordings made between 2011 and 2013. The next release was Engineered Beautiful Blood’s5 signal-i, an older album that Shark Fung and Wei Nan remastered for this release, with the song titles changed. Following these are records from Laek1yo,6 Yuen Chee Wai and Grisha Shakhnes. Laek1yo breaks the mould a bit because it’s probably the most different from the others I’ve done so far. This release, Chicken Rice, is his first official record, as his songs have previously been distributed mostly online as discrete tracks. I’ve played his music on various occasions, but people don’t always enjoy it, perhaps because his approach to spreading political awareness is to piss people off. But I’ll tell you who got into it. I was fined for littering—it was a cigarette butt—and had to do a CWO (Corrective Work Order) at Bukit Merah. There were quite a few of us so we were divided into groups and assigned a supervisor who would tell us where to go and sweep. I played Laek1yo for the other people in my group and it was a hit.

The process of making a record is quite flexible. The musicians know the format, and have a sense of what the length and rhythm is, as long as what they make runs between half an hour to one hour. Even the duration of the A side and the B side is not always fixed, as long as we are able to separate the songs so that the two halves are about even. Once I get the tracks, we master for cassette. I work with an analogue media company based in Canada that is one of the more prominent players in tape production. The interesting thing is that I never get the exact number of tapes I order because they will record until all the tape on the reel is used, so the final quantity hovers around what I request. I’ll keep two for archival purposes, and the rest are sold, or more often, not.

The cassette covers I design myself and print at home. For Awk Wah’s 三接, the image references are from my photographs, including graffiti I documented in a very smelly Queen Street kopitiam toilet, the old Yangtze cinema and Golden Mile Complex. I’ve actually started drawing and painting again because of the cover art I have to do for the cassettes.

I choose what to release based on serendipity, or shared interests, especially when the attitude and outlook that informs our mutual intentions is mostly in sync. I’m planning a total of ten releases, and am about halfway at the moment. The artists I work with have an element of the obscure, and may cross different genres, but what they have in common is that there is something “off” about each one of them. The kind of music I like is like the kind of films I enjoy, I look for new feelings, new-found expressions, things that get my hair standing.

My approach and the artists’ philosophies are reflected in the label’s name. It doesn’t state any aspirations or gesture toward impossibly evolving projections of growth, which we all know is the abstract cause of our failings as a society. Neither does it pander toward some kind of stance against the economy of public taste. In the end, there is not much interest in, or value placed on these releases, and there is nothing in return other than whatever personal joy it brings you. Perhaps expecting anything more than the release itself is just fantasy, but that’s OK.

Images page 134-135 courtesy of the artist