Out, damned spot! out, I say!

One: two: why, then, ‘tis time to do’t.

Hell is murky! Fie, my lord, fie! a soldier, and afeard? What need we fear who knows it, when none can call our power to account?

Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him.

Lady Macbeth1

Seeing spots can give one a sense of disarray especially if one is guilty of scheming someone’s disappearance. Spots have an illusionary quality, captivating in its preposition, yet stubborn in how they remain within our field of vision even after one has looked away. Since being introduced to literature in my teens and being somewhat a neurotic at school (I used to double check my daily actions), I have always resonated with the cautionary tale of Lady Macbeth’s ‘red-spotted’ hallucination: the washing of a pair of imaginary blood-stained hands, over and over again. In thinking about erasure in contemporary art, this example, one of obsession, madness and even possession comes to mind. For this preoccupation of the human condition to erase seems to arise from a general inclination for us to remove or correct an error, so as to make it better.

But we never know what ‘better’ is.

The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has spent a large part her life painting with dots as a metaphor to obliterate her anxieties. ‘Dots’ would fictitiously appear in her daily life and environment ‘filling up and taking over’ her real space.2 Kusama’s ‘apparition’ of dots is to do with an intense psychological inclination to ‘cover up’ negative and positive space so as to arrive at a new paradigm, one in which the dots ‘float like a caste net’. Whether there is a difference between spots and dots, I believe there is a correlation between Lady Macbeth and Kusama as both ‘see patterns’ due to their sense of trauma and anxiety. These recurring patterns seem like abstract translations of their own biological system of cell networks and particles at play. Both imagine these organisms as shapes that come to life either as bringers of anguish or that of relief. One is tormented and eager to remove them while the other sees them as a protective presence, able to calm and bring about a positive change of mind.

Yayoi Kusama

Dots Obsession

2015

Installation, mixed media. Installation view: Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark

Photo: ©YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo / Singapore / Shanghai

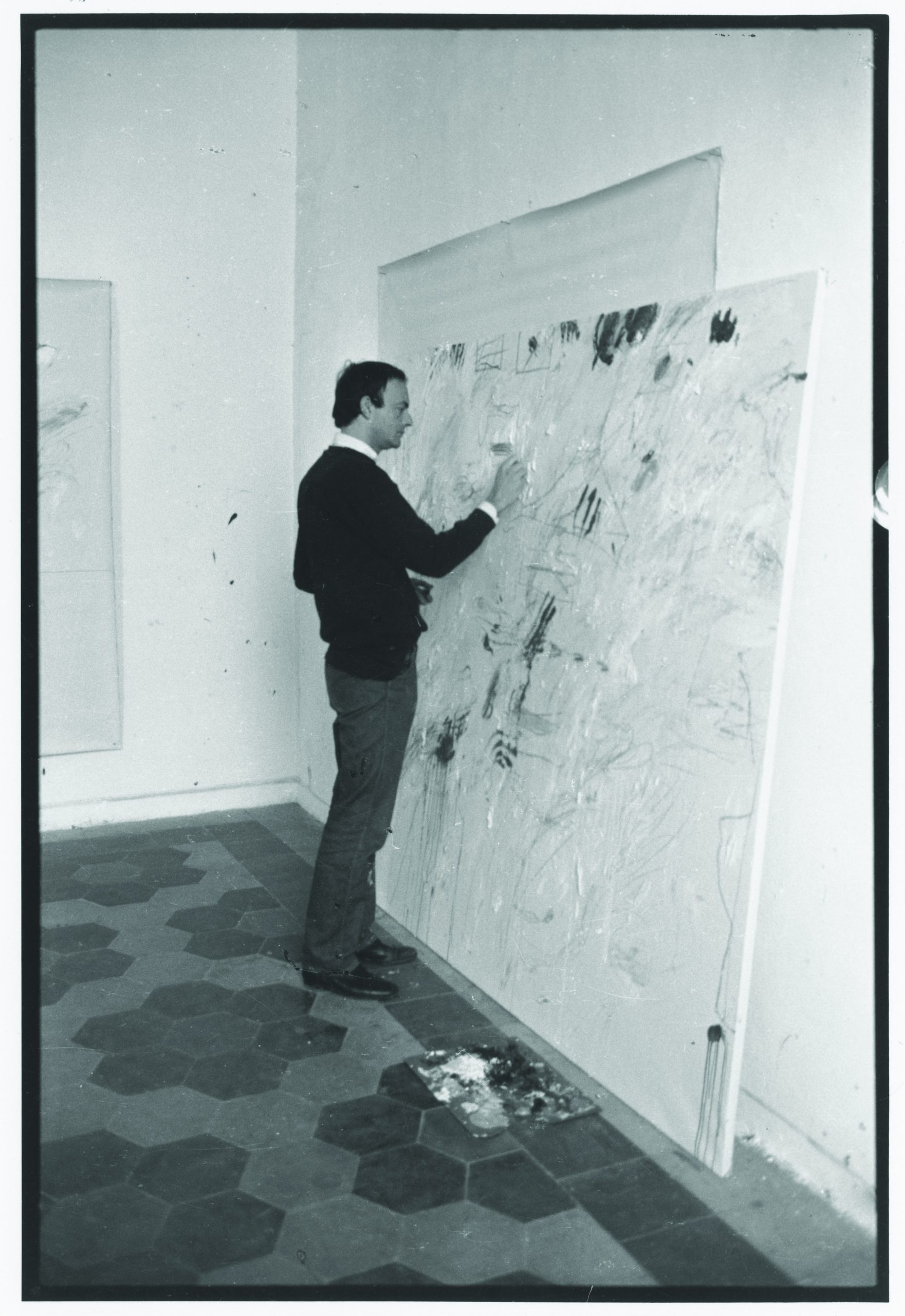

As a young art student, I was told never to apply the colour red as an underpainting. The reason was because any tint that is subsequently applied on top of it would be affected by the warm intensity of its source. Red, once seen, is irreversible to the eye. The colour red appears frequently in Cy Twombly’s paintings. Works like The Ferragosta Paintings from the early 60s and Wilder Shores of Love 1985 tend to emerge as a scattered sprawl of paint, where doodle lines and smudges concur. Lines also appear as writing and can dissolve within a span of a single picture frame.3 Lines also appear as writing and can dissolve within a span of a single picture frame. The rubbing away of information or the covering up of it, make up an overall ‘impression’ of expressionistic debris. It’s as if the act of wiping out connects the distances between each element, resulting in a multiplicity of traces. A Twombly painting reveals parts of its former ‘existences’, some more stubborn than others. Representationally, the act of painting (with sticks, hands and rags) and erasing synthesises and romanticises the biological and psychological. In one moment, pigment can be sprinkled to suggest droplets of excrement and another, an implosion of circular smears as if plants were being caressed or stepped on. The example of red, whenever it appears as a hue, it is either left over from a vigorous application or seen as coming through a mist of white and greys, rubbed away or around by a slight of hand.

Cy Twombly nel suo studio a Roma, 1962

(Cy Twombly in the studio, Rome 1962)

Photo: ©Mario Dondero

Film screenshot of Notebook on Cities and Clothes (starring Yohji Yamamoto)

dir. Wim Wenders, 1989

Photo: ©Ian Woo

Yohji Yamamoto, who once related that he was not a fashion designer but a seamstress, started his career working on clothes by cutting its material to make shapes as a ‘covering and protection’ for the body. For Yamamoto, designing clothes was about looking for the right balance of the asymmetrical and the body.

What is this sense of balance?

In director Wim Wenders’ film documentary Notebook on Cities and Clothes, the protagonist Yamamoto is seen initialising the pillar of his new shop building in Tokyo.4 He signs the concrete surface with a piece of white chalk, stands at a distance and looks. Seeing that it is not ‘right’, he summons the assistant to rub it out while he has another go. The first attempt at signing is almost unnatural as he corrects the curves by drawing over the initial lines he made. The assistant rubs off the chalk with a wet rag in a combination of circular motions, then completes the task from left to right. One sees and experiences the name disappearing from first name to last name. This sequence occurs several times. We are given a glimpse into how when observing someone write, it engages within us opinions of character that are revealed both in handwriting and body language.

What was Yamamoto looking for while erasing his signature again and again? Throughout the repeated attempts, he ponders his last strike, an awkward pause followed by another probing stance. Perhaps it’s the scale of the signature, which is larger than the usual for signing a document. He goes over a clean slate—carte blanche—in short succession, like a sadistic punishment to himself for being so important. An attempt at making a human mark in response to the architecture of its time, performing the ‘perfect’ move so that his name gathers a sense of proportion while relinquishing an effortless dance.

The scene is tense, but why would it not be?

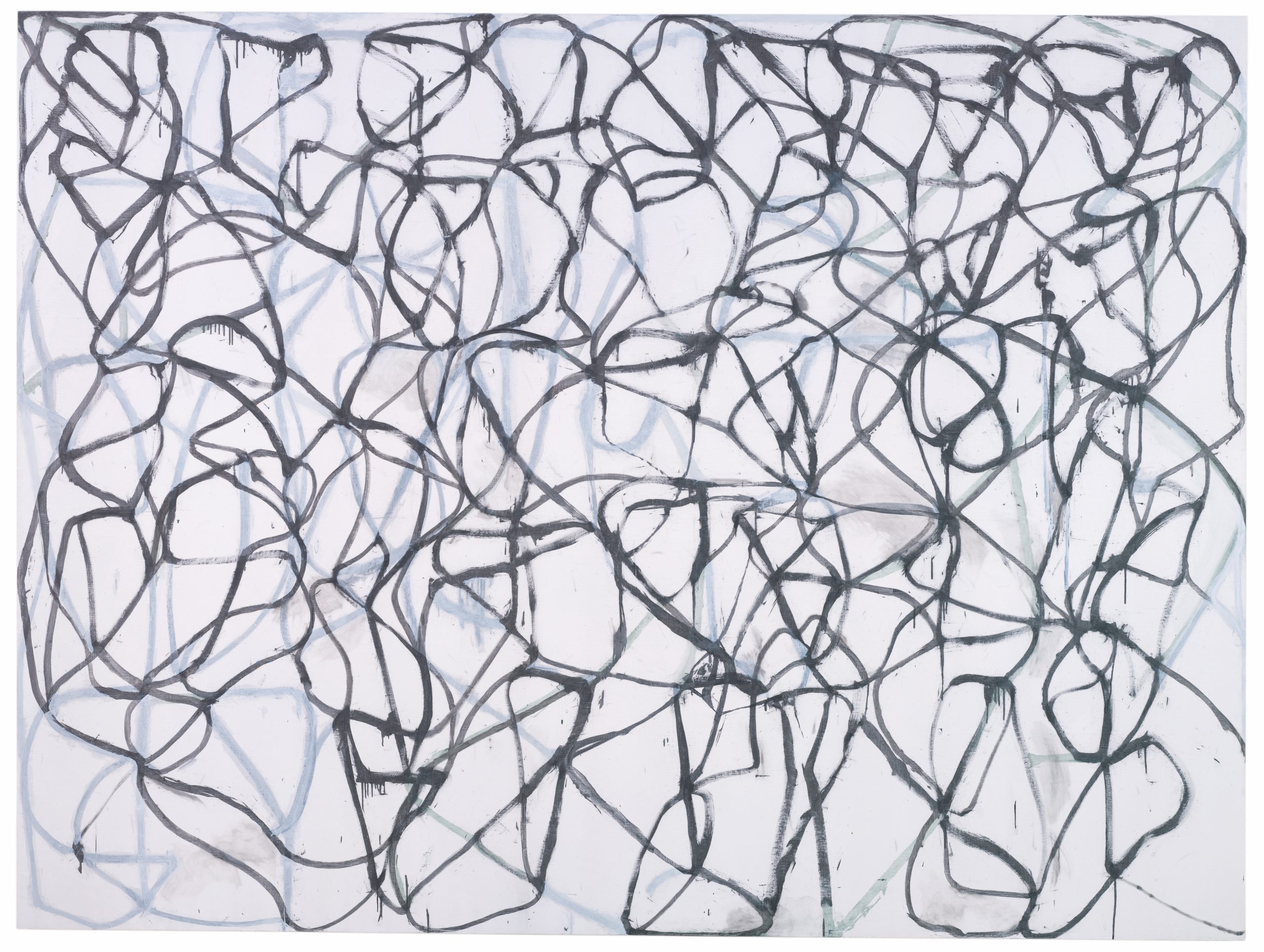

I first came across Brice Marden’s work at a drawing exhibition in London that was curated by the artist Michael Craig-Martin.5 The exhibition, entitled Drawing the Line, contained a work on paper that comprised Marden’s characteristic drawings of interweaving vine-like lines to form a vertical map. Upon closer examination, I saw white paint being used as a corrective material to hide lines that were of no use. It immediately gave me a sense of comfort to know that he made mistakes! The ‘correction’ later reconciled within me the importance of authenticity and ‘doubt’ in the field of art making. Cancelling and concealing with Tipp-Ex are customary methods used in modern-day office work. But in what spirit is it done? With grace or anguish? Marden develops his work in the former as it is with grace that he wilfully and delicately paints over lines and marks that he has drawn. In Marden’s painting, Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge), lines intertwine organically like branches of a plant bending, tilting, twirling to map its way in accordance to an improvisational force. The series of work which was influenced by the Tang Dynasty poetry of Han Shan, hints at calligraphic writing or a kind of structure that suggests the plotting of directions. Lines appear upfront, back and forth, shifting between the space of a picture.6 His initial process involves drawing a layer of lines, which he later paints over them in white. He then overlays a fresh layer of line drawings which move in completely different directions. The correlation of the two gives the painting an airy movement as if the past (covered) and the present, like the growing stages of a plant, are uncovered before us.

Christopher Wool’s paintings remind me of someone wiping off grease while some of the more elegant gestures seem like the repeated figure eights from an ice-skating ring. Usually, it’s fast, like a quick burst of energy released before you. The use of text figure dominantly in Wool’s work, but before any of it gets read, it is usually morphed by painterly disruption.7 Visually, one can see where the image of writing has been shifted and made to move. The paintings seem to be physically made with large movements as if the words did an abrupt exit from the edges of the canvas. Aesthetically, it’s the opposite of Marden’s slow dive. It is made out of black paint, without overlays, very direct, simple like punk music. The final product is less text than ‘all-over’ image, with the painting suggesting the appearance of an incident: an experience of media glitch, the image of sound, or a close-up snippet from a car chase from some black-and-white movie. The ‘erasure’ of a Wool painting is equivalent to the invisible pulse of a city—alive and in motion.

Brice Marden

Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge)

1989-1991

Oil on linen. 274.3 cm x 365.8 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Purchased through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis. Photo: ©2012 Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I discovered 4’33” by composer John Cage and his book Silence when I was an undergraduate student in England. Both of these items dealt with some form of removal of memory, in this case, music as melody. He advocated, in his treatise, the rediscovery of an awareness for the sounds of the real world.8 As a piece of music, ‘4’33” was a three-movement score for any number of performers in which they are not to perform within the specified time and duration. In fact, I once ordered a CD of this particular piece from the now-defunct Tower Records and ended up in an hour-long debate with the sales person about why I should not buy this piece of ‘empty’ music. Since its inception, ‘4’33” has influenced generations of avant-garde contemporary musicians and composers. What it did was provoke an extreme gesture that there was no such thing as silence and that the element of sound, like a piece of found object in visual art, can be considered as real-time music. The idea was to merge the boundaries that govern our audio perception of the world. This provided a ‘passport’ that inspired many musicians to explore timbres and overtones, the extraneous sounds from instruments and the natural environment.

A composer whom I found interesting in his use of erasure in sound recordings from our environment as an instrument was Alvin Lucier. In his iconic music recording and performance of I am sitting in a room, he reads aloud the following self-reflexive text:

I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now.

I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed.

What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech.

I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.9

The reading of the above information was recorded and played back repeatedly, each time, gradually emphasising the sound of the frequency and acoustic timbre between the voice, room, microphone and tape machine. At some point, the audio information is no longer audible, but is instead replaced by a pulsing loop of cascading rhythms veering towards feedback. Here, there is a ‘taking over’ of the narrative data by a technological ‘ghost’ which is ‘captured’ by the methods of recording. The sound recording device as an apparatus is unlike that of a brush or rag for painting, but it is used to emphasise the phenomena of body and atmosphere. Abstraction as sonic form is the indeterminate cast, shaped and captured. Akin to the layered bleed of ink on a sheet of paper, erasure as a positive rather than negative activity has taken place. The speech of Lucier’s voice is another kind of ‘handwriting’, characterised by the tremor of the voice like the increments of a person’s handwriting.

My first son, Asher, keeps a sketchbook of animation illustrations. Recently, I found him using a piece of paper as a protective layer to absorb the bleed of the markers from infiltrating the rest of the papers. The resulting ‘protective material’ fascinated me. It was an image in which the history of his ‘decisions’ made from the entire sketchbook was captured to create its own animation. I related this to Lucier’s methods of recording where an element of distortion had been built up by a machine. The absorbent paper in this sketchbook was no different from the machine. The distribution and overlapping of ink marks and animated figures regathered to form a manga palimpsest. In addition to this discovery, it also resurfaced the use of negative information, or rather, support systems of art as ways to discover the ‘unknown’, or rather, ignored activities of the mind and body.

Asher Woo

Absorbent paper from Asher Woo’s Manga sketchbook

Marker on paper

29.7 cm x 21 cm

Photo: ©Ian Woo

In 100 Layers of Ink, Yang Jiechang uses the idea of the arbitrary task as a means to merge the concept of ink painting and Chinese history. The Chinese revolution had ‘put away’ the relevance of ink painting from her people.10 This relevance is the poetry of space and time which characterises the invention and awareness of poetic phenomena in early Chinese paintings. This ‘empty’ space as ambiguous perspective is also the basis for the development of abstraction in America, specifically in the works of Willem de Kooning and Robert Rauschenberg. In fact, Rauschenberg had famously ‘erased’ a drawing of de Kooning’s as a way to ‘find’ what was ‘left’ of it.11 Interestingly, Yang’s approach here is the opposite of subtracting. This is also due to the materiality of ink painting where liquid dries to reveal a state of being. Once ink is dried, it is irreversible. The only way is to layer on top, creating two or more illusions of space or matter depending on the context of what is being expressed. But essentially, Yang sees the act of overlapping in his painting as a form of reduction as found in his interview extract with Li Yu-Chieh:

Li: Is this a kind of addition?

Yang: Well, if you repeat this boring gesture every day, it becomes a means of reduction. I studied a technique fundamental to Song and Yuan dynasty painting in which colours and glue alum solution are applied repeatedly to achieve the saturation of colour: three layers of glue alum solution and nine layers of colour. For example, the red would be a bit transparent but it has many layers and differs greatly from when you apply it only once. 100 Layers of Ink employs a similar technique. Black became not just black; there is light in it.12

Saying that black has a form of light through his layering methods, Yang sees his approach as a way to create a kind of space. This space is complex as layers of the ink’s crystallisation is indeterminate, caused by the way the mineral of the ink dries over what has occurred before.

Yang Jiechang

100 Layers of Ink—Silent Energy

1992-1993

Set of 6 paintings, ink on xuan paper and gauze, 410 x 290 cm (each)

Installation view of Silent Energy, Museum of Modern Art Oxford, 1993

Photo: ©Yang Jiechang. Courtesy of Yang Jiechang

If we think that Yang’s use of ink is mystical and abstract, then another example of using the concept of appropriation as well as a similar layering of ink can be seen in Qiu Zhijie’s painting entitled Assignment No 1. Copying the Orchid Pavilion 1,000 Times (1990-95), a photographic documentation of the process of calligraphic learning and writing. Zhijie uses a poem composed in the fourth century by Wang Xizhi as a starting point to overlay the Chinese characters over each other 1000 times on the same sheet of paper to create an ancient and rudimentary form of time lapse.13 This performative act can be read as both a reflection and subversion of the Chinese literati tradition. In contrast to Yang’s pure black space, this work sees the build-up of writing in ink, smudged while morphing from information to material. A change, generating the concepts of learning and memory buried through repetition. Here, erasure as cancellation is an animated critique of a dissolving legacy.

The weight of history is one of the challenges every artist faces within the 21st-century climate of political instability and upheaval. The surreal and grim disappearance of the twin towers has become a key moment in contemporary history that marked how we should be wary of our cultural assumptions or the ways we communicate with each other. In Every Page of the Qur’an, Idris Khan scanned 1953 pages of the Qur’an using a version of his father’s book. It was an experiment suggested by his father, using technology and photography as a way to compress time and image. Khan was also, at the time, influenced by the writings of Roland Barthes and Susan Sontag, authors whose ideas commented on the methods and nature of image reproduction.14 In repeating and overlaying images and texts by digital scanning, a quality of depth develops similarly to the ways in which a computer is able to pick up details through pixilation. This develops into a dense overlay of stacked data, which at some point, begins to pick up the fissures and atmospherics of the image rather than the information. The process also disrupts the precision of the scanner’s eye, allowing the indeterminacy of layering to conjure up an x-ray version of a book that is ‘read simultaneously’ in time and space. This, together with the history of the Qur’an as subject-matter, provides the viewer with new insights into both the still life as a ‘sacred object’ and the ‘Word of God’ as a possible image. The superimposition brings together the new and old technology that celebrates the faith and currency of Islam.

Idris Khan

Every… page of the Holy Qur’an, 2004

Lambda digital C-print mounted on aluminium, 136 cm x 170 cm

Installation view of A World Within, The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2017

Photo: Jonathan Shaw

When you start working everybody is in your studio—the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas—all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you are lucky, even you leave.

John Cage paraphrased by Philip Guston15

The above anecdote had stayed with me since graduate school. An idea like this was important especially for someone coming out of art school and going into the real world. Cage’s resonance about artistic vision, the courage to be different and that last line, “even you leave” is not for everyone. Taken in its entirety, it’s almost a religious calling for a life of dedication and service. Some would say this could be a rather dangerous thing. But it actually sounds rather positive, an encouragement that if you keep at it, you will find something. Here, erasure is seen in the practice of art as a gradual distancing from attachments and influences; to not be sentimental, to move ahead into the unknown.

To erase, whether by removal or building up, situates the eccentric man as of two minds in the search of new forms of communication. From text to speech, signs and symbols, erasure enhances the visual and sonic, heightening the ‘felt’ of the artist’s ‘personality’ trait. These forms of articulated sensibilities reach for ideas of existence that are complex, embracing the primal and intuitive while challenging accepted notions of the rational and proven world. To erase is to make unclear something that previously was or thought to be sufficient in its status. It is to highlight the ‘blur’ as memory, the appearance or disappearance of matter as encounter or visitation; a suspended moment in time to the observer or listener in question. Erasure situates and highlights the body and material world as phenomenological evidence of man’s decisions and actions. Erasure edits and essentialises to ‘discover’ itself.