Erase (v.)

c. 1600, from Latin erasus, past participle of eradere, “to scrape out, scrape off, shave; to abolish, remove.” Of magnetic tape, from 1945.1

McDonalds Trabant, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Being

“Between the experience of living a normal life at this moment on the planet and the public narratives being offered to give a sense of that life, the empty space, the gap, is enormous.” – John Berger2

My grandfather was incarcerated in a Russian Gulag from age 16 to 21. Once released, he sailed the world on merchant ships, and settled in a country (Germany) he had never lived in before. In and out of prison, reluctant to submit to (absolutely any kind of) authority, he became a serious alcoholic and died young. Unless drunk he never spoke, but then no one wanted to speak to him, neither his wife nor his children, themselves also damaged people. And then there was me.

I was the only one he agreed to speak with, and so, while I lived with them during bouts of homelessness, I became the one through whom the others conversed.

My grandfather’s stories were vivid, always the same, tortured; they revealed modes of torture that damaged his body and mind forever. In response, I continually made up stories about superheroes and avengers. In their company, my grandmother and mother expected me to be like them. Stop talking. Stop making up stories. Be silent. Be silent. After all, they were silent too. They could not unlearn the idea that speaking was dangerous. Only my grandfather really spoke (when he chose to), perhaps at me, but certainly into me. I loved him. I was seven when he said that I, too, was torturing him with my questions, that they made holes in his belly, and he showed me that belly, which was indeed full of holes.

Towards Erasure

Today the vast majority of dominant cinema, regardless of genre, mode or even thematic concerns, feels like a childhood toy: something to hug, something to remember fondly, something that finally reassures, and which, as a result, can effectively be forgotten. It has lost its activating fuse, producing an international cinematic conservatism and passive audiences, upholding what film-maker Peter Watkins as long ago as 1967 termed the ‘monoform’: a delivery structure where all the complexities of life, society and history, regardless of the severity, mundanity or grace of the themes, are reduced into the same formal narrative engine, as predictable and recognisable as a famous fast food chain, and offering a similar ‘comfort’.

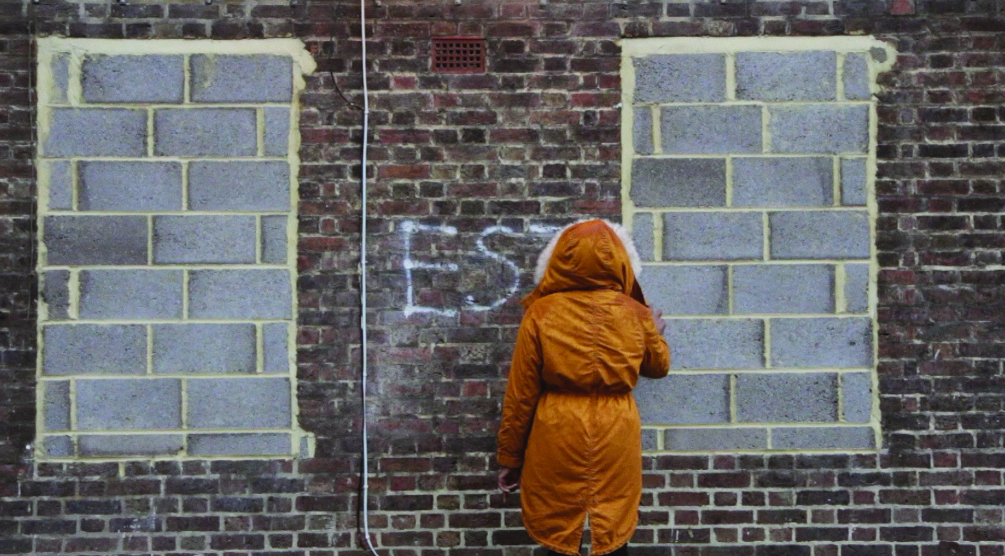

Estate, Fugitive Images

Before its workings are understood, the power of cinema is often evasive, slippery. At the opposite end (its result) is what is often termed powerlessness, a feeling that accompanies the sense of being made invisible, insignificant, a voice that does not count. However, what surfaces, closer to obstinacy, rather than resilience, is a making visible, and not in response to erasure, but regardless of it.

Here I will explore, though my own approach to making films, various manifestations of and challenges to power (especially in its ‘behind-the-scenes’ identity, from covert military operations to city planning). For the past 10 years my work has focussed on the often under-explored and under-expressed intersections of public and private memory, especially in relation to place, communities and to structural and political violence.

Estate, Fugitive Images

Throughout, my approach has been socially collaborative, in content, form and production. Formally, my films seek to open (for both the participants and audience) a space for consideration of the shifting border between documentary and fiction, using long-term observations, interventions in real-life situations, re-enactments, found materials, archival traces and ‘always the honouring of lived experience.’ I seek an ethically engaged, culturally resonant expression of shared humanity, and a co-existence with larger ecologies (beyond human-centred subjectivity).

So…

I have set out these criteria:

To reject the erasure of place, history, relations and difference.

To acknowledge my own lifelong experience of these concerns, and the class expectations and restrictions that accompanied my own journey into an understanding of these structural assaults.

To find a visuality that is not only in opposition to (or merged with) the erasure as we, in different ways already experience it, in our surroundings, in our bodies, in our minds, and in our ways of sensing each other.

To enable a making and embracing of an aesthetic that allows for the presence of ambiguities, of a tone that might be called troubling, unsettling (unable and unwilling fully to be reconciled or resolved) and yet, in spite of that, to voice a complex solidarity for and with each other.

To understand that each film is a form of making and briefly finding ‘home’, a moving from being-forced-to-dwell-inside one structure to making, along with others, another structure in which the existential complexity of our life in the world as we find it (and seek to make it) is allowable.*

Against Erasure of Place

Estate a Reverie (2015)

Estate, Fugitive Images

Estate, a Reverie speaks to and of a city long inhabited by a huge diversity of communities (whether focussed around ethnicity, nationality, belief, gender or sexuality, and not forgetting, of course, finance, class and vocational groupings), a territory whose complex identity is at stake within the unfolding and accelerating narrative of globalised gentrification or ‘development’. It is a zone whose buildings, functions and populations are being challenged by ‘incursionist’ forces—of speculative capital, architecture and commerce—threaten the current spectrum of ways of being in this location.

The film tries to make sense of a process that is regarded in public discourse as inevitable, one that declares public housing in its original sense to be dead, made obsolete by the market ‘choices’ of a neoliberal world, one shaped by both finance and consumer capitalism.

What is the movement, subtly, of perception, accompanying this shift? The privatised city (including militarised domestic vehicles, private healthcare, schooling, roads and more) has at its mirror image, the ‘other’. We often cannot precisely ‘see’ how power works, and mostly we do not even notice it, until we (some bodies more than others) are subjected to its full force.

Clichés and stereotypes in policy and commentary are reinforcing ideas of the abject, alongside an accompanying sectional ‘public’ fear. This instigates a further spread of the private sphere (structurally, legislatively and mentally) into the public realm, intended to make certain groups of people ‘feel’ they are not welcome: not welcome to participate, unable to, and in fact undesired. Strangers in their own time and place.

Estate, Briony Campbell

Estate, Fugitive Images

I had lived on the Haggerston estate in East London for most of my adult life and campaigned for many years alongside other residents to get the buildings repaired. Decades of neglect and intentional underfunding meant that they were in terrible condition. We were not successful in saving them and, once I knew that the estate would soon be demolished, I started filming.

It feels important to note that Estate has not been made ‘about’ this community but has been made ‘from’ it. Through a variety of filmic registers and strategies, the film seeks to capture the genuinely utopian quality of the last few years of the buildings’ existence, a period when, because demolition was inevitable, a refreshed sense of the possible, of the emergence of new, but of course time-specific, social and organisational relationships developed, alongside a revived understanding of how the residents might occupy the various built and open spaces of the estate.

Crucially, the film challenges what a documentary about housing might look like and be, even at this time of acute crisis within UK provision. I made a very conscious decision to move away from the statistical and expository towards a poetics of everyday life.

Estate focusses on the ‘structure’ of its eponymous architecture not only because it is where we lived, but also ‘how we lived.’ The film explores the multiple implications of what most explicitly defined us to other people, while simultaneously challenging that often all too monocultural definition and revealing the complexity and breadth of the population it housed. The film seeks to counter the many myths and clichés of our mainstream representation with a celebration of spirited existence and asks how we might resist being framed and objectified through externally imposed ideas towards class, gender, (dis)ability, economy and ethnicity, and even simply the building in which we sleep and wake.

Against Erasure of Difference

Taskafa, stories of the street (2013)

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

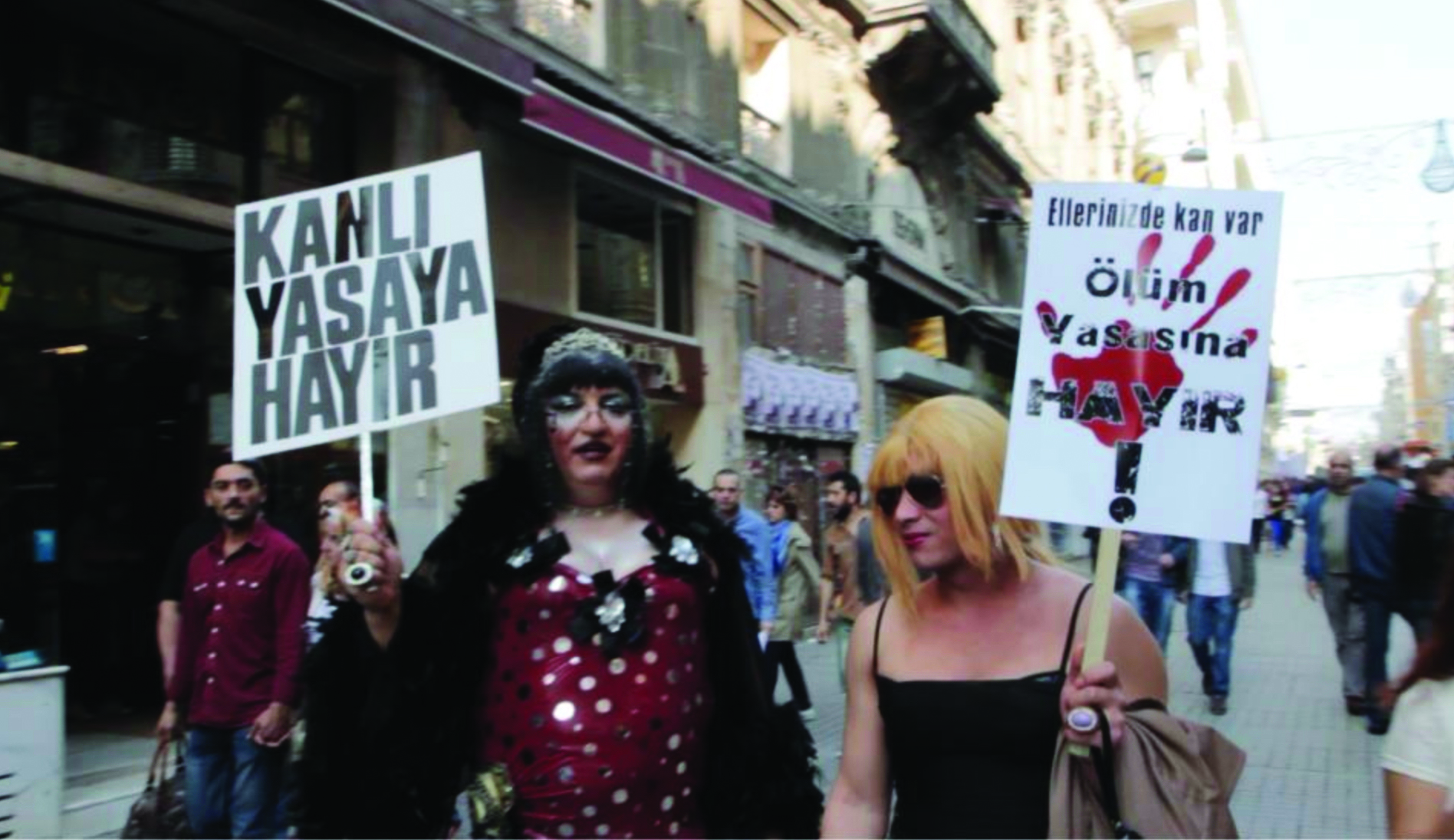

Taskafa (from the Turkish: stone-head, hard-headed) is a film about memory and the most necessary forms of belonging, both to a place and to history, through a search for the role played in the city by Istanbul’s street dogs and their relationship to its human populations. Through this exploration, the film opens a window on the contested relationship between power and the public / communities of the city. It challenges categorisation (in location and identity) and charts the ongoing struggle / resistance against a single way of seeing and being.

Despite several major attempts by Istanbul’s rulers, politicians and planners over the last 400 years to erase them, the city’s street dogs have persisted thanks to an enduring alliance with widespread civic communities and neighbourhoods, which recognise and defend their right to coexist.

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Taskafa, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Taskafa gathers the voices of diverse Istanbul residents, shopkeepers and street-based workers, all of whom display a striking commitment to the well-being and future of the city’s street dogs (and cats), free of formal ownership but fed and cared for by numerous individuals. Navigating from the rapidly gentrifying city-centre district of Galata to the residential islands of the Sea of Marmara and beyond, Taskafa maps a history of empathy with, and threats to, these distinctive urban residents.

I had collaborated on the film with the late John Berger, whose novel King gave me the key to the story. King, a story of hope, dreams, love and struggle, is told from the perspective of a dog belonging to an economically and socially marginalised squatter community facing disappearance, even erasure. In Taskafa, this voice is gifted to a wider community and imbued with a range of perspectives: to dogs, a city and, finally, to history. Berger’s text and delivery accompany the viewer on a journey from Karaköy to Hayirsiz Ada, the island where, in the 1800s, tens of thousands of dogs were exiled to die.

Offering a moving collage of testimonials on the inestimable value of non-human populations to the emotional and psychological health of the city, together with a striking statement of witness to advocacy and persecution across the centuries, Taskafa both portrays, and embodies the spirit of protest and enduring solidarity on which it closes (with a mass demonstrations opposing the latest municipal proposals to clear the city of its street animals).

Taşkafa is not finally about dogs as such. It is about the way people seek to belong, still and ever more so now, to a larger context than themselves, one which respects other creatures and wishes them to play a significant role in their lives. The key issue is not whether we live securely, especially in its ‘official’ sense, but rather that we do not lose touch with the shared reality that surrounds us.

Against Erasure of Histories

Erase and Forget (2017)

Erase. Courtesy of Bo Gritz

“You already know enough. So do I. It is not knowledge we lack. What is missing is the courage to understand what we know and to draw conclusions.” – Sven Lindqvist3

Lt. Col. James Gordon ‘Bo’ Gritz turned 80 this year. ‘The American Soldier’ for the Commander-in-Chief of the Vietnam War was at the heart of US military and foreign policy—both overt and covert—from the Bay of Pigs to Afghanistan. He was financed by Clint Eastwood and William Shatner (via Paramount Pictures) in exchange for the rights to tell his story. Their funding supported his ‘deniable’ missions searching for American POWs in Vietnam. He has exposed US government’s drug running, turning against the Washington elite as a result. He has stood for President, created a homeland community in the Idaho backlands and trained Americans in strategies of counter-insurgency against the incursions of their own government. What does it mean to have lived a life like this? Gritz’s life is a contested, contentious and very public one, unfolding glaringly in the media age. It is a life made from fragments, from different positions, both politically and in terms of their mediation.

Lights, Camera…

In Erase and Forget my interest is not merely in what ‘really happened,’ but in the actor’s historical becoming, the context of which remains contradictory, able to be assembled only from shards. My experiments with role-play, re-narration, re-enactment and the montage of ‘document’ and ‘fiction’ have been part of a methodological quest to find an expression that promises no immediate or direct access to historical truth, but whose processes articulate and analytically ‘perform’ the dramatic, narrative and generic conditions of the production of historical truth and its personnel.

It is a way of exploring relationships between image, memory and historical representation in a context—covert operations—where such explorations are fraught. It is therefore a film about films, the making of historical actors and ‘superheroes’ in order to justify an enemy. And, crucially, it investigates structures of concealment instead of invisibility, where a profound unmaking of the possibility of seeing with our own eyes is in operation.

The imbrications of Hollywood mythmaking and national policy formation reach back to the first half of the last century. It was not merely that Hollywood directors were seized by the hubristic urge to shape the extraordinary dreams and everyday opinions of the masses, but rather that figures within the administration actively sought to harness such hubris.

Here, fiction cinema offers an access point that allows for both the recovery of logistical detail and the plotting out of a historical mise-en-scene of which such details are elements. Fiction creates reality. Hollywood and political structures in the United States are tightly knit. On a material level, there are exchanges of personnel and funds. Hollywood regularly employs (often retired) covert operators and military staff as advisers, and the story rights of military operations often become the properties of major studios. Where the purchase of such rights is, by definition, often after the fact, on occasion funding precedes the event.

The flow of finance and support between Hollywood and the military is not unidirectional. The Pentagon contributes by providing army assistance (advisers, helicopters, use of bases, etc…) to productions that it deems supportive of US policy. Such films inform the climates of public opinion within which that policy operates. They open imaginative spaces and arenas of ethical consideration in which certain kinds of military operations are validated. Furthermore, Hollywood cinema serves as a curious, discursive space for policy makers (and thus for speechwriters as well as scriptwriters). Ronald Reagan, on numerous occasions, publicly drew on the Rambo series to articulate his foreign policy vision and configure his political aspirations.

…(Covert) Action!

Gritz was part of a world where deniability lies at the forefront of action on the uncertain line between knowing and unknowing. The spectral nature of covert operations lies in their being, officially, ‘neither confirmed, nor denied.’ Thus, the spectral is produced by official discourse, but admissible to it only as that which cannot be admitted. However, rather than a product of official denial, it is the outcome of ‘deniability’. This involves not the denial of a particular event but denying official authorisation of an event.

Dislocating action and intention, cause and effect, creates a shadow realm from which strategic operations march forward like zombies—an operation appears to have been carried out in the absence of an originating order. The action is spectral in as much as it seems to escape the laws of causality that govern the rest of the world—it is an effect without identifiable cause.

The spectral can be thought of as power’s penumbra – precisely an effect of the potential to ‘project power.’ Indeed, the potential for covert operations is variously publicised: covert operations are an acknowledged instrument of policy. Thus, spectrality is more an effect of an administration’s covert operations capability than of any particular operation. Thus, the spectral issues from the encounter between a highly publicised capability and the mechanics of deniability.

While any given mission may be invisible, the spectral threat of those missions is often broadcast in a spectacular fashion. The very visibility of Hollywood renditions of covert operations does nothing to diminish their spectrality. On the contrary, the spectral subsists in the spectacular: if it is the penumbra of power, it is also the shadow of the spectacle.

Covert operations are institutionally accepted as an essential instrument of government policy and today, of course, increasingly privatised. Thus, without the need to invoke shadowy conspiracies, the very machinery of democratic governance produces a host of spectres.

When an image (page 24) of Gritz and his Cambodian mercenaries who fought the ‘secret war’ in Laos was published in General Westmoreland’s memoirs A Soldier Reports (1976), Francis Ford Coppola, making Apocalypse Now (1979) (based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) and narratively transplanted to the Vietnam War) asked for permission to use this image, with the intention that Marlon Brando’s (who played the renegade US Colonel, Kurtz) face be pasted over Gritz’s. This request was refused by the Department of the Army.4

In 1979, Gritz had given up his formal military career to prepare for his prisoner-of-war recovery mission, Operation Lazarus (1982-83). Lazarus was short of money, and this shortfall was collected from various sources. William Shatner, otherwise known for his role as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, helped bridge the gap by providing US$10,000 in exchange for the rights “to tell his (Gritz’s) life story.” Clint Eastwood provided the remaining US$30,000 in return for an unofficial option on the story rights to the mission itself.

Thus, a future history was at once made possible and purchased. The story of prisoners of war brought home, or in other words, returned, through the initiative of one man operating beyond the law and without official sanction, was just the kind of patriotic tale of heroism and redemption that Hollywood was hungry for. However, a restaging of the mission (i.e. the Hollywood film) depended very much on an initial staging congruent with the conventions and dictates of its Hollywood paymaster.

Erase, Andrea Luka Zimmerman

Operation Lazarus generated sensationalised news coverage on all three major US networks, as well as triggered a campaign to discredit Gritz. He claimed he was prepared for the smears and suggested that his mission, at the highest levels, had a different ultimate objective: was not my idea. I got a letter. Perot admits General Tighe called me to conduct a covert mission into Laos. They thought that because I was Westmoreland’s soldier, if I say there aren’t any, then there was closure on this issue.” See also Gritz’s testimony before the Senate Select Committee Testimony & Depositions, November 23rd, 1992: General Eugene Tighe, Director, DIA, requested H. Ross Perot sponsor a private effort to determine whether or not any U.S. POWs were left alive. “Perot called me to his EDS, Dallas office in April 1979. He instructed me accordingly: ‘I want you to go over there and see everyone you have to see, do all the things you need to do. You come back and tell me there aren’t any American prisoners left alive. I don’t believe it and I’m not interested in bones.’”’]“not to recover prisoners of war but to confirm their non-existence.”5 Effectively, what the administration wanted was a spectacular illustration of absence, and the high visibility of ‘nothingness’ was intended to banish the spectres of those supposedly still missing. So, having initially conjured the spectres as a means of prolonging the war and then as a means of negotiating the peace, the administration now wanted to banish those spectres through the spectacle of the covert operation.

Of course, the very notion of a spectacular covert operation is paradoxical. As is the fact that Gritz was chosen to lead the secret mission precisely because of his visibility. In the end, Gritz never returned with any prisoners, but each return was haunted by the spectre of prisoners that his very missions were involved in producing.

In the same period, William Casey (CIA Director during the Reagan years) brought in some of the country’s top public relations firms to advise him on how to sell his two pet projects—supporting the Contras in Nicaragua and the Afghan Mujahedeen—to a dubious American public. He called this “perception management.”6

Ronald Reagan, at the 1988 annual Republican Congress fundraising dinner said, “by the way, in a few weeks, a new film opens, Rambo III. You remember in the first movie Rambo took over a town. In the second, he single-handedly defeated several Communist armies, and now in the third Rambo film, they say he really gets tough. It almost makes me wish I could serve a third term.”7

There is another, rather less widely distributed film that stands as testimony to the Reagan government’s dedication to the ‘Gallant People of Afghanistan.’ Untitled and shot on Super 8 sound stock in the fall of 1986, it is the record of a ‘secret’ training programme for Afghan Mujahedeen on US soil.

Most of the training was carried out in a disused mine in Sandy Valley, not far from the small desert town in which Gritz was and remains resident. At one stage, the footage shows Gritz winding up a detonator cable leading to a huge plastic container-bomb that explodes in spectacular fashion. It leaves behind an enormous crater in the desert earth and is cause for enthusiastic cheering from a largely off-screen crowd. A little further into the reel, Gritz, presiding over a bucket of ball bearings, instructs his traditionally clad Afghan trainees in the making of homemade claymore mines. Explaining what will happen once the many ball bearings penetrate their targets, he makes the allusive suggestion to “just think of it as Hollywood.” These bomblets are baked in apple pie tins and then detonated in close proximity to human-shaped paper targets. After the explosion, Gritz inspects the targets and shouts triumphantly: “All the Commissars are damaged!”

After the post-9/11 US investigation of Afghanistan, editors at a local US news outlet, Channel 8, cut their bulletin item to footage of Rambo. The voiceover explains the unorthodox editing: “You’ve heard of the Hollywood Rambo, who ploughed the cinematic jungle of South East Asia looking for American POWs.” On screen, we see Rambo in a shooting frenzy, firing a 50mm cannon. Rambo shoots the gun from his hip, which is followed by a match-cut to Gritz shooting an even bigger gun, also from the hip. As Gritz shoots, the television voiceover continues: “We’ll meet the real deal, Bo Gritz.”8 The report then went on to reveal the American locale of the Afghan training.

Television conflates Gritz with the fictional Rambo in order to make sensational news. By conflating them, and thus sensationalising the covert, what Channel 8 does is to occlude the conditions by which Gritz’s Afghan training was made. Everything singular about this film is erased, including the terrible events from which it emerged. By producing Gritz as ‘the real deal,’ television produces the irrecoverable historical real (i.e. the past) as merely a parasitic supplement of fiction.

Spectacular realist fiction, then, precedes the events upon which it is ostensibly based. And this is something of an inevitability in a mass media environment which rehearses as well as scripts the conditions of sociability, namely those common fictions through which the world can be apprehended, those conventions that allow for a popular imagination to distance itself from the violence that underpins it.

The violence of Channel 8’s treatment of Gritz’s Afghan training film seeks to erase its detailed relationships with the past—the discursive conditions by which it can be received as evidence of something other than the spectacular performance of a fictionalised character. James ‘Bo’ Gritz becomes the ‘real’ Rambo, for the media (and to himself) because it serves the media precisely to be able to talk about ‘real life’; and it serves Gritz to reinvent himself as the ‘real deal,’ to suture himself into a mise-en-scene in which his own carefully collected documentation can be apprehended as evidence, and be celebrated as a hero. As Gritz says, “Why should I act like Hollywood when it is Hollywood’s job to act like me?”9

In summary, then, we can see how Reagan plots out his foreign policy imperatives along the trajectory of the Rambo franchise, which reciprocates by riding and intensifying the wave of euphoria generated by the apparent success of that foreign policy. There are interesting parallels between these public policy statements, the spectacular renditions of that policy’s effects, and Gritz’s own film record of one of the covert operations that embodied the policy’s strategic implementation. This record becomes an element in the public construction of Gritz’s character, used as it is in the local Channel 8 news report. This construction erases—precisely through violent spectacle—the actual violence of which Gritz was an agent. Gritz participates in this violence through the directorial relationship he forges between himself and Rambo as a fictional character, which finally entails reducing his utterances to fictional clichés.

Erase, courtesy of Bo Gritz

The word ‘secrete’ has two senses that appear to be in peculiar tension with one another: to exude, and to make secret. It is this peculiar tension that informs the relationship between spectacular representations of covert military operations in cinema and the spectral violence of the actual ‘theatres of operation.’ On the one hand, Hollywood is willing to create the conditions of possibility for covert operations so that it might then recover them in spectacular fashion. Shatner and Eastwood both funded covert missions with an eye to their future Hollywood renditions. In this sense, Hollywood has the capacity to secrete a spectral violence. But this secretion, in order that it might be successfully recovered as spectacle, must be secreted as secret. The covert operation must be ‘secret’ in order to be authentic. Here, then, the covert operation is pretext for, and projection of, its own spectacular re-enactment.

This process of secretion, however, is chiasmatic. The covert operation may, in some instances, secrete its own Hollywood creation (for example, Eastwood claims Gritz’s proposal was that he, Eastwood, stage a faux action movie production on the Thai-Laos border to serve as cover for Gritz’s mission). Here the spectral secretes the spectacular in order to make itself secret.10

It is this process of mutual secretion, of projection and reflection, that Erase and Forget aims analytically to perform. The insertion into a fictional scenario of a historical actor whose biography is purportedly the basis of that scenario’s script is a strategy that has yielded rich results. This mise-en-abyme strains the coherence of both the biographical and the fictional scripts, and in so doing, reveals the generic imperatives that guarantee these discourses’ very coherence.

Against Erasure of Relations

Here for Life (2019)

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

A collaboration with Adrian Jackson, founder of Cardboard Citizens (a theatre company comprised of homeless and former homeless people, whose acting method is based on Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed) and the performers, Here for Life, travels alongside 10 Londoners. All have lives shaped by loss and love, trauma and bravery, struggle and resistance. They grapple with a system that is inherently stacked against them.

They dance together, steal together, eat together; they agree and disagree, celebrate their differences and share their talents. They cycle, they play, they ride a horse. The lines between one person’s story and another’s performance are blurred and the borders between reality and fiction are porous.

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

Eventually they come together on a makeshift stage in a place between two train tracks. They spark a debate about the world we live in, who has stolen what from whom, and how things might be fixed.

We felt it important to make this film now, with those who are engaged in a daily struggle with the structural violence of our society, as they are so readily exoticised, victimised and ‘othered’ in a number of different ways through widespread and repeated cultural tropes. We worked with our troupe over a long period of time in order to work through these issues, and to allow the participants agency over their stories. So, together, we explored what stories can be told, across and beyond difference and fixed ways of seeing and feeling. Perhaps most importantly, our film seeks a tenderness in this search, in both the making and expression.

I am a perennial observer, wishing to understand how images may be opened up to show us the richer variant meanings contained within them. Misconceptions about one another are largely structural, then internalised as if they were personal, inevitable traits or failings. It has so much to do with relatability. And misconceptions, of course, are shared across these intersections. This awareness played a significant role in our working with the troupe, and also with ourselves: starting from our own stories, what we share, and then how we might give life to another’s story without simply assimilating it into a dominant narrative.

Making a film with people always includes questions of (self) doubt / censorship (what we exclude because we see it from a particular position, fear, etc). This film is about storytelling in a literal as well as more associative sense, where the specifically situated, through rigorous examination and open telling, might speak to the ‘universal’, to the common ground.

For…

My intention in each work has been to create what I could call an activating metaphor; an image or concentration of form that is both actually itself undeniably in the world and also an energising metaphor of larger concerns. In Taskafa, it is the canine; in Estate, the building; in Erase and Forget, military conflict—both overt or covert—speaks to many other ruptures. And in Here for Life, the squatted performance ground holds and meets the marginalised bodies / lives of the film’s performers.

Here for Life, Zimmerman, Jackson, Artangel

I am informed here by what Angela Davis (and others) have observed about the need for new metaphors that convey the truth and lived experience of our times. She says, for example, for most women, people of colour and working-class citizens, it is much less about ‘hitting a glass ceiling’ in which reaching this far are the privilege of only those few, than it is about staying steady on a ‘collapsing floor.’ I am with those who are trying to stand.

Seen

In The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (1973), the late Ursula K. Le Guin tells of lives lived in a city of harmony, peace and happiness. When the citizens of this settlement learn that their peace is dependent upon the condition of one child kept in darkness and squalor, initial outrage is soon followed by a general forgetfulness of this suffering. However now knowing, and unable any longer to stay within the city’s wall, some choose to walk away. Le Guin writes that: “The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away…”11

*End Note

Three of the films surveyed offer perspectives from the ‘margins’, as it were, from people who live restricted lives within majority structures and find, by various means, ways of co-existing in frames more of their own making (even if temporary). In these terms, it might appear that Erase and Forget is a spectrum pole apart, a commentary from inside one version of that majority structure mentioned, and in this case arguably its apex, the ‘military-industrial complex.’ However, Gritz’s own experience of that machinery lie in closer proximity to the others than might first appear. The working-class son of a combat military family, with few employment options open to him, Gritz’s life (through his own experience and understanding of the workings of power) has turned an inherited class and economic marginalisation into a personal even philosophical one, and has led him to make his own forms of ‘home’, successfully or otherwise, in a variety of locations and scales, where the practice of a direct engagement with social need and aspiration has been as necessary as in the other cases.

Acknowledgements

My thoughts above emerge from many conversations, for Taskafa with John Berger, Gülen Güler and Bill McAllister; Estate with Lasse Johansson, David Roberts and Ruth Marie Tunkara; Erase and Forget with Michael Uwemedimo; Here for Life with Taina Galis, Therese Henningsen and Adrian Jackson. With gratitude to Gareth Evans for his invaluable contribution over many years to my thinking these things through.