… to make a stone feel stony, man has been given the tool of art…By ‘estranging’ objects and complicating form, the device of art makes perception long and ‘laborious’ …

—Victor Shklovsky1

… You can pick up any given stone anywhere in this country and can be certain that something happened at that very place in those dark times, too … —Michaela Melián, in conversation.

… The iterability of the trace (unicity, identification, and alteration in repetition) is the condition of historicity—as too is the structure of anachrony and contretemps …

—Jacques Derrida 2

Plath, Nils. The Trace of Stones and Memory Work: Michaela Melián on the Historicity of Re-representations. In ISSUE 08: Erase. Singapore: LASALLE College of the the Arts, 2019. pp. 81-105.

Like so many others, this city is built on sand. The city, any city, our city that continues to challenge us to reflect, in the words of Paul Valéry,3 on how it creates and shapes us, in its role as a surface and ground for the many assemblies that Judith Butler dedicated some notes to in recent years, concerning the future of democracy.4 One where the “descent of structures to the street” took and takes places, as Jacques Lacan pointed out to Michel Foucault, looking back at the May of 1968.5 A ground on which to position oneself temporarily, in view of the history in which youthful demonstrators here and elsewhere, once upon a time 50 years ago, seemed hopeful of discovering an unlikely utopia, seemingly promised in one of their popular slogans, which was coined by the protagonists of the Situationists International and painted in translation across many walls, not only those in what had been known as the ‘Capital of the Nineteenth Century’6: “Sous les pavés, la plage (Beneath the pavement, the beach).” Even deeper run the layers here that Sigmund Freud failed to mention in Civilization and its Discontents, where he came up with the analogy of the city of Rome as the human psyche7: 13,000 feet underground, the oldest volcanic stones from the geologic era of the so-called early Permian era, almost 290 million years old; then 6000 feet of mighty salt crusts and 2500 feet of cap rock (coloured sandstone), 890 feet of Muschelkalk, 446 feet of Keuper, and finally 164 feet of loose sediment from the Quarternary period. Sealed by artistry and craftsmanship the ground covers the results of several thrusts of the Scandinavian inland ice and multiple tectonic movements during thousands of years and many long-forgotten reigns, which created these layers invisible to the human eye. In this city, the stone floor made for walking is traditionally composed of slit massive, polished granite rocks millions of years old from the Silesian landscape, each about three by four feet, enclosed by random rows of small cobblestones that run like a mosaic along the fronts of the houses and the edge of the sidewalks. This pavement pattern remains the signature of the public sphere in this city, even when, over time, other natural and prefabricated stones have supplanted the cut and worn-smooth granite rocks in more and more areas. It is this city, the capital of more than one Reich, that had witnessed its own destruction into rubble. Pedestrian sidewalks: a regular texture over which couples and passers-by come together and part, where they head to a destination or meander aimlessly, meet or disregard on-comers, where they invite attention and long to be watched, only to finally disappear behind the facades or in the next side street. Eighty years later, with some massive interruptions and breaks in local and global history, these sidewalks are also crowded by those who have no choice but to conduct themselves as Bertolt Brecht advised illegal and political activists in the poem in his Handbook for City-Dwellers from 1939—a book that might be still purchasable from the second-hand bookseller around the corner:

Part from your comrades at the station

Go into town in the morning with your coat buttoned up

Find yourself a quarter, and when your comrade knocks

Do not open, O do not open the door

But

Erase the traces!

If you run into your parents in the city of Hamburg or elsewhere

Pass them like a stranger, turn a corner, do not acknowledge them

Pull that hat they gave you down over your face

Do not show, O do not show your face

But

Erase the traces!8

Right here on my block, as well as elsewhere, the arrangement of the signature stones is broken up in front of several building entrances. Single concrete cobblestones, bearing a brass plate with engraved names and dates, have been embedded in the mosaic. Markers of events from a still-current past that most will gloss over without awareness; these events can be read about in the preface of another book long out of print and possibly found on the shelves of bookstores. It is a preface that connects stories about streets and locales with very personal memories of one of the most crucial days in German history:

I remember being eight years old; one night, lying in my room facing the main street, I was suddenly woken up by a loud, high pitched sound. At first, I thought I had heard laughter, and once I was fully awake I perceived a clanking noise, the loud shattering of glass, and then the dull thuds of riding boots, with shouting in between. Then, a shrill cry was audible, more yelling and muffled voices, and at the end of it, engines started up, their sound soon receding. The next morning I saw a completely wrecked and ransacked store. The shop window with the name Hertz was in smithereens, and among the shattered glass on the sidewalk I remember seeing red spots washed over with water. 9

Engraved on the so-called Stolpersteinen—literally, “stumbling stones”—are the names, dates, and some very brief information about the fate of those who lived in those houses at one point, those who were deported and murdered during the Nazi era in Germany. As the result of a private initiative, more than 70,000 of these stones have been placed in the sidewalks of many German and European cities and towns since 1992. As impediments or obstacles, they are meant to make the passers-by pause and reflect upon the history of the place in memory of those victims. Yet, the stumbling stones are not uncontroversial, and not everyone embraces them as well-intentioned memory aid. While some property owners dislike them and consider them perpetual eyesores, others view them with good reason as examples of an all-too-simple mode of remembrance, as a form of memory kitsch. A vocal part of Munich’s Jewish community rejects them as an inappropriate means of commemorating the dead and has circumvented the laying of any stones in the city, arguing that they would only invite desecration and that stepping on the names of the ones murdered would be disrespectful and degrading.

Instead, since 2010, Munich as the capital of the state of Bavaria has a virtual memorial for the victims of National Socialism: Memory Loops by the artist Michaela Melián. Multi-layered and large in scale, intangible, highly complex, and made to incite a shift in one’s perception of the visible layers of this city, where the Bavarian royalty formerly resided, the piece comprises 475 audio tracks—300 in German and 175 in English. Each one of the tracks is a collage of one or several voices thematically tied to the individual location in the cityscape. All of them can be downloaded or listened to online (www.memoryloops.net) or via phone on site. Memory Loops—an intermediate work that has garnered several art awards—recounts the history of the city the Nazis called the “capital of the movement,” by using historical materials from the time of National Socialism (NS) and later accounts of witnesses, describing the discrimination, persecution, and exclusion to which people in Munich—Jews, oppositional political activists and resistance fighters, the gay population, church members, Romani people, and others—were subjected to under the NS regime. Michaela Melián, who studied art and music in Munich, is deeply connected to the city, as an artist who has worked there for decades. Today she lives in a nearby Bavarian village. In her works, dating back to the 1980s, Melián focusses on body and gender politics and issues, on memory work, and on representations of German history. She applies multiple media in her work: using installation and performative formats, producing classic works for the wall and on paper, as well as audio works, radio plays, and recordings on vinyl and CD, as well as sound works for public spaces and the internet.

The following conversation took place in early 2019 in Hamburg, Germany, where Melián works as a professor of time-based media at the Hochschule für bildende Künste (HFBK). It was conducted in German and translated into English by Nils Plath:

Nils Plath

Can you say something about how you developed Memory Loops, its structure and various elements?

Michaela Melián

First, it is important to know that for this invitation-only competition, I came up with the idea for a monument that had no preconceived or designated location in town to start with. Because the politicians involved could not decide on a place where to put it. I had gotten the impression that they hoped somebody would come up with ideas that allowed them not to sacrifice a piece of property at all. The complex history of Munich is the very reason for this. All the prominent locations it would have been destined for—like the Odeonsplatz or the Königsplatz—are in the heart of town, but do not belong to the city. It is the state of Bavaria that has the say over them. And while the city government that had this idea for the monument for the victims of National Socialism in Munich was a progressive one at the time, the state was ruled by a conservative right government. The two do not share any common ground when it comes to cultural projects. When invited to participate, I thought the whole thing would just be a dud, something that would not come off, and would not be realised in the end. That is why I came up with the idea for an immaterial work of art, an audio work. I also find it highly problematic in principle to place a symbolic stone somewhere in the public sphere so that it then serves a political function. While certain city tours lead to it, of course, most pedestrians and drivers passing by are unaware of what it stands for. It is nothing else but a form of official political relief effort to come to terms with the past symbolically. To counter this, I wanted something different. It was my idea then to somehow tell a story about this uncannily massive history of erasure that had taken place here—an erasure of personal narratives that depict politics, as well as life itself. Thus I thought of ways of how to recount stories and histories from lives back then, which might happen today, too. Thinking about this makes me, in fact, a bit wary and fearful in today’s world. I knew there were many sources, oral histories that a generation before me, the one of 1968, had already collected and saved. Eyewitness accounts from survivors. Most of the materials were scattered in various, often private archives—of documentary filmmakers, for instance. Like Katrin Seybold’s; she was a leftist filmmaker and writer who did a lot of research about the family and circles of Sophie and Hans Scholl, members of the resistance group Weiße Rose who were both murdered by the Nazis. As well as about the lives of Romani families and communists. For a long time, her films were hardly shown in official institutions, because she was regarded as a sympathiser with the radical left. I was lucky that I got access to some of her films right before her death, and I used passages from several of her works for my audio tracks. Today, parts of many of her films can be seen at the NS documentation centre in Munich, where they are part of the permanent collection. I also used other people’s archives, as well—radio journalists’, for instance. And from the Dachau concentration camp memorial site. The latter was originally initiated by former inmates. They did not want to lose their memories and started recording each other’s stories early on. My first sources were those audio files that I had transcribed. That was a very labour-intensive endeavour. Most of the material had only been published in excerpts, never in full. It was my idea to link particular traces to particular locations in the city. So that it all would form a nexus or network of stories that could be tracked and explored. At certain locales there would be clusterings: the police headquarters being one of them. Several different stories took place there: some policemen’s, as well as the story of a demonstrator taken into custody, stories of Romani people and communists. Some of their stories would continue at different places: the train station for instance, because someone was arrested, or deported from there. And so on. The stories allowed me to weave a matrix over the entire cityscape. The research was very time-consuming, and it took long hours to transcribe everything with the help of students. Followed by half a year in the studio for the recordings, and the score that accompanies all of the tracks. While already in production, we continued to develop the project to see how to connect the stories with each other in the best possible way. And in coming up with more ideas on how to program it all in order to make sure that listeners are not guided all too much. It was important to me not to take the listeners by hand.

Nils Plath

In order not to create a didactic piece of work…

Michaela Melián

I did not want to design just another guided walking tour or course through town that you just have to follow. It was my aim to enable everyone to come up with her or his own narrative path while listening. To explore new layers every time. In the beginning there was still the idea to devise some kind of guided tour that would get visitors from one important site to the next. But it would have meant giving them instructions on how to progress through the city. I wanted to avoid that by any means. And guarantee the experience of a more mental tour of their own.

Nils Plath

What I find striking about the project is how different layers of time collide. How experiencing Memory Loops makes you realise the asynchronicity of the various spaces present at once. All the documents and witness accounts continue into the past and the future. They force us to wonder how laws and ordinances came into effect in the first place, and what this could mean for our own future. At the same time, when experiencing the public sphere through the audio files, you can think of the many other events particular places in the city have seen: the Bavarian Soviet Republic of 1919 for example, the days of the Olympic Games in 1972 (and the Munich massacre by Palestinian terrorists), or the gay life of Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Michaela Melián

That is exactly it. All places allow for various interpretations, invite them; the architecture embodies several moments at once. And in the case of many laws, it is very apparent how they continued to be like echoes from the past. Section 175 had long-lasting repercussions. [It was a provision of the German criminal code that made homosexual acts between men a crime in 1871; it was broadened by the Nazis in 1935 and brought thousands of men into concentration camps. The law was not removed from the books until 1994.] Those men affected could not apply for indemnity without outing themselves and thus running the risk of being prosecuted again in postwar (West) Germany. This is just one strain of the many terrible, enduring situations in the German legal system. Without specifically alluding to them, those are connections I narrate with the help of different tracks.

The various sources I used should make it clear that very different forms of narratives are possible when constructing a history and images of the past. There is one track in which you learn about all the cultural events that took place on November 9, 1938, the day of the pogrom. It is 12, or maybe even 15 minutes long, and lists every movie and every theatre performance on that evening. When listening to the narrative voices and hearing the names of theatres that are still there today, you cannot but wonder what the audiences must have seen on their way home. The Münchener Kammerspiele, one of the leading theatres in town, is right across from where an orthodox synagogue, a school, and a kindergarten once stood. It is quite clear that people who walked home from the theatre must have passed by and seen what was going on that night. But why do we only have the eyewitness accounts of the victims? My father was the one who made me aware of this. He was a child back then, ten years old, and a member of the choir for the opera house. They performed that evening, and got out rather late, and had to walk by the synagogue. If kids had walked by there that evening …

Nils Plath

… where were the ladies in the fur coats? And what did they witness? And what did they erase from their memories?

Michaela Melián

Exactly, we do not have any public accounts from them. My dad only told me about his memories when I inquired about it. I was curious to find out how it felt for him to live in Germany back then, as the son of a migrant worker, coming from Spain, in this very nationalist society. That is when he told me about witnessing that November 9th.

Nils Plath

This is already an answer to the question about what you think are some of the “strong motifs,” as the author and filmmaker Alexander Kluge calls them, in your own work. Because of how analytical they appear to be, your works do not seem to deal with you as a primary figure at first glance. There is a certain sense of distance at play. And yet, your works cause viewers to ponder questions about belonging and origin, about the historical contexts we are part of, and thus, the role of observer and producer, of which you are an integral part.

Michaela Melián

As an artist, I always found it very difficult to take myself as the starting point for inquiry. That is not what I wanted. There are many female artists in a certain feminist tradition that make their own faces, their own bodies the first point of analysis. I am interested in a more conceptual approach: a mode of translation. This has a lot to do with me, too, of course. It is very much my own mode of translation, my way of analysis. For one of my works, titled Studio, I rephotographed rooms, inspired by Virgina Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. I wondered what rooms in which a female artist can work in would look like. This is still a pressing matter today: How to divide work and life, how to integrate it? This is why rooms became of interest to me. From the study of Karl May, the inventor of the German notion of the Western who never travelled to America; to Sigmund Freud’s consulting room and couch; to Eileen Gray’s studio and the rooms at the Weissenhof-Siedlung in Stuttgart, an offspring of the Bauhaus. In many of the photographs and Xerox copies I took, my own hand is present while holding the book or turning the pages. I am in the image. And then I connected all of the reproduced black and white images by hand, by stitching them together with colored thread. There are very personal aspects like this in many of my works.

[In his “Theses on the Concept of History” (1940), the theorist Walter Benjamin—for whom questions about housing were also of foremost importance for his thinking on aesthetics and politics, because he saw them as central for the various notions and realisations of concepts of work and social existence, the individual and the collective—marks the point that historicism “virtually erased” the memory of the revolutionaries and theorists of the Paris Commune of 1871. In the seventh of his theses, Benjamin writes: “And all rulers are the heirs of those who conquered before them. Hence, empathy with the victor invariably benefits the rulers.”10 It is not only the historical materialists mentioned by Benjamin who know what that means, and what it means to try to come to terms with the fact that, as he writes, the cultural treasures “owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” With her various works produced over the course of more than three decades, Melián is part of this very tradition as a critical observer of the history of erasures in various strands of history writings affecting the multiple and asynchronous here and now. Her interest for a long time had lain primarily with the effacing of female protagonists and their creative and critical productions in art and culture. That was a starting point. Visualisation became a way for Melián to counter the dominant forms of the transmission of cultural artefacts and ideas from one owner to the other (always tainted by barbarism, as Benjamin had pointed out) as well as the perpetual constructing of a certain lineage through which the self-acclaimed “victors of history” (Benjamin) attempt to legitimise themselves.]

Nils Plath

Since the early works in the 1980s and 1990s, a number of female figures have appeared prominently in your work (such as Tomboy, 1995), such as Emma Goldman, Tamara Bunke, Erika Mann, Bertha Benz, Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Patsy Montana, Renate Knaup-Krötenschwanz …Those were comments on the erasure of female figures from the histories of culture, politics, and art … and signs for upholding traditional hierarchies and the patriachichal order …

Michaela Melián

I was looking for female role models. I wanted to see how to shape a context for work and life, and how others had coped with the challenge. It was difficult enough then to get some information about certain women who interested me. Emma Goldman, for instance. There were just a few feminist archives and initiatives one could contact and correspond with via post. Today, all research seems much easier. But it is still very surprising how much is lost forever or difficult to rediscover. I noticed that once again during my current research about some of the highly prolific women from the Bauhaus. Very little is known about many of them, and very few to none of their works are still there. The internet promises permanence, but things do disappear. Or they were never present in the first place. Much of the information about my parents’ generation never found its way into the archives of the World

Wide Web. These are facts and processes that we have to be critically questioned. I am interested in finding these gaps or vacancies, to either fill them in my own way, or shed light on why they might be there …

Nils Plath

You were trained as a musician at the conservatory in Munich before studying art, then became a founding member of F.S.K. (Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle), which started as a well-regarded art school band in the early 1980s and still exists today. You have also released three solo albums of electronic music on one of the leading music labels in Germany—Monika Enterprise. Music seems to play a much greater role than ever before in your artistic work in recent years, too.

Michaela Melián

It is totally true that the music and audio plays a more crucial role now. After studying music, I was convinced that I could only ever perform in a band context. F.S.K. was of great importance for me, as an artist collective and platform for discourse. All of the members were involved with different artistic forms of expression: Thomas [Meinecke] as a writer, Justin [Hoffmann] as a curator, Wilfried [Petzi] as a photographer and documentarist of exhibitions, Carl [Oesterhelt] as a musician. We had our very own discursive apparatus. As it was for so many in my generation, it was most important for me not to limit myself to one mode of expression or one medium. What I learned from playing in the band was how to avoid identifying with something that might be taken for granted as a given entity. We were all about rejecting the idea of the origin and all notions of originality. Instead, we aimed to deconstruct the myth of artistic existentialism and therefore re-appropriated found materials…

Nils Plath

Attempting your very own form of participant observation … in accordance with Roxy Music’s slogan “Remake/Remodel” … 11

Michaela Melián

Absolutely. Adapted to ever-new circumstances and conditions. That is still very valid for me today. I was educated by the band, and I find nothing more appalling than the claim that you do what you are or have become. There are certain motifs and themes I continue to pursue, of course, and particular procedures are important for me. But I want to readjust them constantly and make them fit for contemporary modes of viewing.

Nils Plath

… as well as listening. Your exhibitions most often transform public locations or galleries into audio spaces. Temporarily. Making one aware of the often invisible histories of architectual places and their utilisation that affect the way we perceive meaning via sight and sound. From Ignaz Guenther House (2002), to the most recent radio works performed at the broadcasting hall of the Deutschlandfunk.

Michaela Melián

That came over time, when it was getting easier to realise certain audio works. With the help of the computer, of course. As an artist who could only afford so much for producing new works, it made a big difference to me to be able to record my own audio tracks. I have always worked with galleries, but I did not have access to great budgets. The computer changed the game for me. It was also a historical turning point, because many female artists started to record and produce. Even though there are still not enough of them. I got really involved in this audio world, because it started to be great fun for me and I realised that I know a lot about it. During my time at the music conservatory, I even considered becoming a sound engineer at one point. I think the importance of music in my work is still growing.

Nils Plath

One could say this audio practice is another mode of weaving or stitching for you. Materiality has always been a focal point in all of your works. In a previous conversation you stated that it is all about incorporating theoretical reflections into the materiality of the individual work. One can see this in the various needle-and-thread works of yours, as well as hear it in your most recent release, the album Music From a Frontier Town (2018). As a kind of homage to Don Gillis’s eponymous tone poem from 1940, you used a selection of audio tracks from the record collection of the Amerikahaus in Munich (a cultural centre run by the US government) consisting of 1630 LPs that were left behind when it closed in 1997, to record four movements, with audible scratches and grooves.

Michaela Melián

For me, weaving is a pivotal practice. Because there is never one standpoint that can be taken as undisputed, because things are all related. Multiperspectivity is always a given for me, and I have yet to take a stance and position for myself. I am interested in marking modes of production that have a certain allure. And problematise their own contexts. This is what draws me to time-based art and media. I like the fact that these works can potentially withdraw from the art market, are easier to reproduce—think Andy Warhol and Walter Benjamin—and more difficult to archive and be sold. The complex relationships of the narrative and the structure necessarily demand some sort of translation that leaves the analytical behind and finds a new artistic expression in and through the handling of the work’s material. It is a rather difficult task to forget about the analytical, or to let it sink in, so that other transformational forces can take over. What I like about music is that words are often unnecessary and that music can affect the body in its own, very unique ways. It can be very seductive. Words can play a role, as well as the materiality, of course. It is usually a long search for me. The work must not be a mere illustration. So much is certain.

Nils Plath

Music has something ephemeral about it. In the early 1990s, your husband Thomas [Meinecke], who also works as a radio DJ, once told me that he preferred talking about sounds and music on the radio than writing about them. Because on the air, words can be send off so perfectly, instead of fixing them in print on a page, he said. What kind of notion of history is inscribed in your work? All of them seem to be informed by a certain site-specificity [even very different works, such as Bertha Benz (1998), Festung (1999), Triangel, (2002), or Electric Ladyland (2016)]. They convey some institutional critique of historical writings [Rückspiegel (2009), Speicher (2008)] or a salute to impactful predecessors [Sarah Schumann und Silvia Bovenschen (2012)], and often deal with female representations. A point of contact seems to be a certain interest in the structure for social coexistance or living together…

Michaela Melián

The social, yes. The contexts in which life is made possible. In the end I am interested in the history of ideas of artists that indeed tried to have an influence. Starting with Bertolt Brecht and Walter Benjamin … where analysis meets poetology. And at the same time a utopian longing. I would not want to forget or erase that.

Nils Plath

Not to forget or to erase a certain utopian longing … do you mean in their work or in yours?

Michaela Melián

Both in theirs and in mine. Can art change something, is a question often raised. You cannot put it that way, of course. But there can be a longing within yourself, that it could potentially have that ability. As something that you hope for and can incorporate, even if only in very subtle way. So that it might be deciphered over time or conveyed in unforeseen ways. Such things do play a role. What fascinates me most about artistic production in general—be it in the so called fine arts, literature, or film—is the delivery of a certain worldview or a snapshot in time of a historic situation. The very best art work on the Holocaust is Claude Lanzman’s film Shoah. The author or artist is very visible in it. Even if you think that he goes too far when he shows up some of the people in certain moments of the film, it still remains a great statement and a very important work of art.

Nils Plath

… especially due to the length of some scenes and the film’s duration as a whole, nine hours, which makes it impossible to conceive and comprehend the film in its entirety.

Michaela Melián

You can’t forget about it, once you’ve seen it. There are images as well that have such an impact. With many layers. Paintings from the Renaissance, for example, might apparently convey a religious content, but simultaneously also transport other layers that provide a closer look at some sociotheoretical contexts—gender relations, the relations between church and state, the economic conditions of the time. I find it fascinating how artworks allow you to immerse yourself in them. I find that exemplary. My own view of history might be a time-based, historical image; and while I am interested in the places where I work and live, and the places I’m familiar with, it is Germany that I am interested in as a country. A country with a history that makes us stumble everywhere.

Nils Plath

Germany is the environment where you hit upon traces of the Shoah anywhere you go, you once stated in an interview about Memory Loops.

Michaela Melián

Every institution—even the ones founded after 1945, owing to their predecessors—and every family history is marked by Germany’s past. You can pick up any given stone anywhere in this country and can be certain that something happened at that very place in those dark times, too. I find it important to bring that to mind today, when many are newly attracted to old ideas of racism and nationalism.

Nils Plath

A search for traces is what your work entails. Traces of the circumstances that got others and you to the site where you meet [like Föhrenwald, 2005, a reconstruction of the history of a small community near Melián’s home, a former work camp and camp for displaced persons after WWII]. You do deliberately avoid the German term Heimatkunde in it, this compound word that cannot simply be translated into English as “homeland studies,” because of Germany’s haunting past. [An exemplary past (in its negativity) that some in today’s world like to erase from the collective memory once and for all; whereas art works show a decisive resistance towards closure, all too easy attribution, and populist amnesia—like those paintings by Gerhard Richter displayed in 2016 under the title Birkenau, or the memorial for the victims of the Shoah in Hamburg-Harburg’s city hall square (near where Melián teaches), conceived by Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz: a 12-metre lead-covered pillar erected in 1986, meant to be written over, that was then lowered into the ground over the next seven years and thus became a symbol for the burying of memories.]

Michaela Melián

I have a troubled relationship with the term Heimat (homeland) … because it is just a construct. Naturally, I was born somewhere, but I feel a sense of belonging only where my longing or yearning find some correspondence. That can be in a very different place from the one I was born in. And maybe even far from where my mother tongue is spoken. Right at the time of the German unification, our band tried to distance ourselves from this new German Heimat, after we had invested quite some time and effort into researching and rerecording some of the remains of German and central-European musical traces in the U.S.A. in the second half of the 1980s. It became clear to us that there was a new positive stance towards German nationalism in the country, which we rejected and did not want to be part of. This missing sense of belonging and the sense of being uprooted also play a dominant role in my own work, along with the longing to leave one’s country or town of origin that sometimes is implanted over generations. The idea of trying to find a better life somewhere else can be strong, and can yet also create some ghost pain when one feels rejected and unwelcome in the new place.

Nils Plath

This attention to people’s longings and to socio-political determinations is something that spans your entire body of work, from the early works dedicated to Tania Bunke, Che Guevara’s East German girlfriend, to your latest works for bridges over the river Rhine in Cologne, for which you referred to the history of the composer Jacques Offenbach, who had a Jewish family background in Germany.

Michaela Melián

This attentiveness comes with my looking at the contexts I grew up in as a musician and an artist. Not seeing many professional female musicians making it on the classical circuit while I was studying music, and even fewer composers and conductors. And then finding out about women in the arts, through Fluxus. I have always tried to discover potential spaces that enable the procedures necessary to realise my interests and my work. How can one combine a specific female longing with a professional longing? Who are the potential role models? Circumstances might appear to be better today, with much more information at hand. But that does not mean that the struggle is all over. Far from it. As Silvia Bovenschen once stated: When resources grow smaller, everything is subject to renegotiation. Not the greatest prospect, for sure. We will see.

In his essay on some of Bertolt Brecht’s poetry, Walter Benjamin commented on the last verse of the poem quoted above:

‘Make sure, when you turn your thoughts to dying

That no gravestone reveals where you lie

With a explicit inscription indicting you

And the year of your death, which convicts you!

Once again,

Erase the traces!’

This instruction might be the only one that is already obsolete; taking care of the illegal has already been the on-going task of Hitler and his men.12

One can count no less than 53 Stolpersteine on the sidewalks of the four streets surrounding my block, one of them named after the German national poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one other being the address of the only synagogue in the city that was not torched during the government-organised pogrom in November 1938 (although still vandalised and desecrated), because neighboring apartment buildings are so close they would have been in danger of also going up in flames. These are the names on the stones: Richard Benjamin, Charlotte Benjamin, Bertha Jacoby, Josef Nadler, Frieda Plotke, Benno Itzig, Hedwig Itzig, Heinz Itzig, Hans Witkowski, Frieda Witkowski, Lieselotte Witkowski, Jakob Schmul, Anna Schmul, Jenny Basch, Kurt Salomon, Clara Oberski, Max Keil, Gertrud Keil, Ruth Keil, Georg Herrmann, Gertrud Herrmann, Alfons Themal, Julie Bernstein, Karin Jenny Ascher, Anna Krone, Margarete Krone, Zilla Krone, Paul Francke, Selma Schubert, Martin Lwowski, Hedwig Holschauer, Wolfgang Gehr, Käthe Gehr, Franz Gehr, Hedwig Wolfsohn, Else Wolfsohn, Julius Oppenheim, Ernestine Zeida, Haim Zeida, Karoline Frey, Fritz Frey, Lilli Reisner, Alfred Nathan Reisner, Paula Baer, Caspar Baer, Joachim M. Aronade, Esther Weiss, Hanns Kornblum, Sally Kornblum, Josef Chaim Weinberger, Anna Weinberger, Irma Noomi Weinberger, Norbert Naftali Weinberger. Almost all of them were deported and murdered. Some committed suicide after suffering humiliations and being deprived of their rights. Two of them were able to escape on child transports to England or into exile to Palestine. One survived the camps.

Michaela Melián

Föhrenwald

2005

Double slide projection with sound, 160 slides + 1 CD (Master), 59:35 mins

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

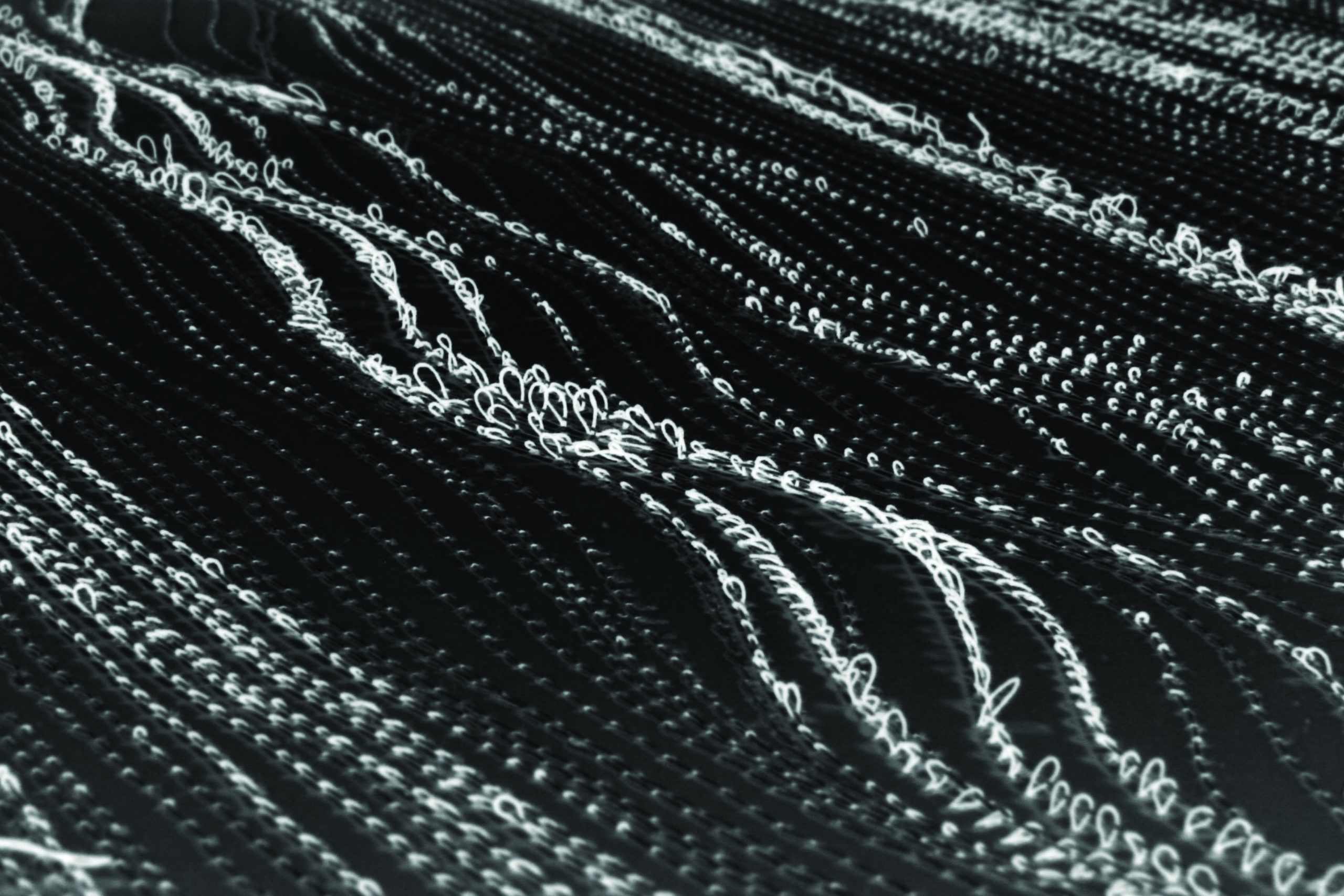

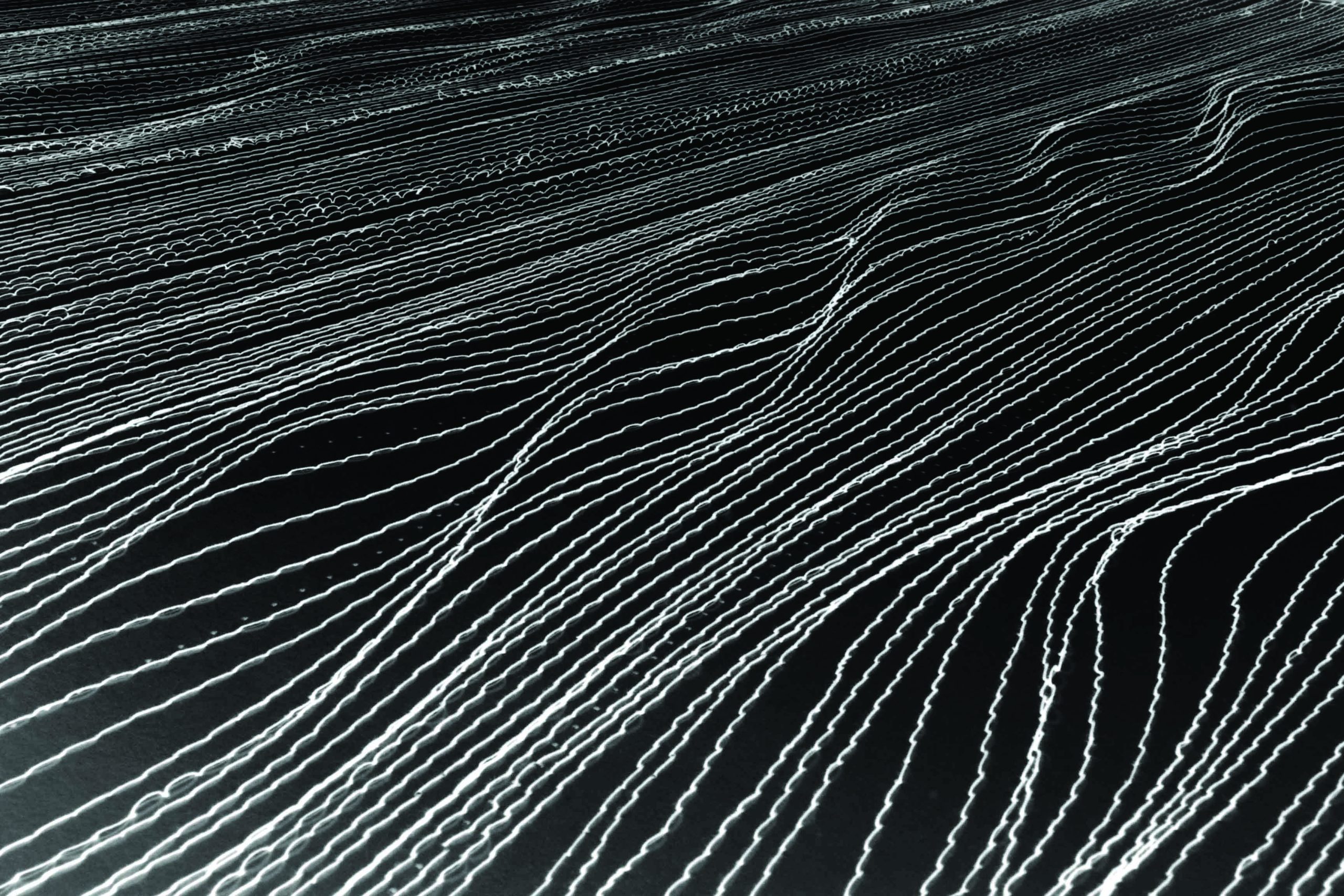

Michaela Melián

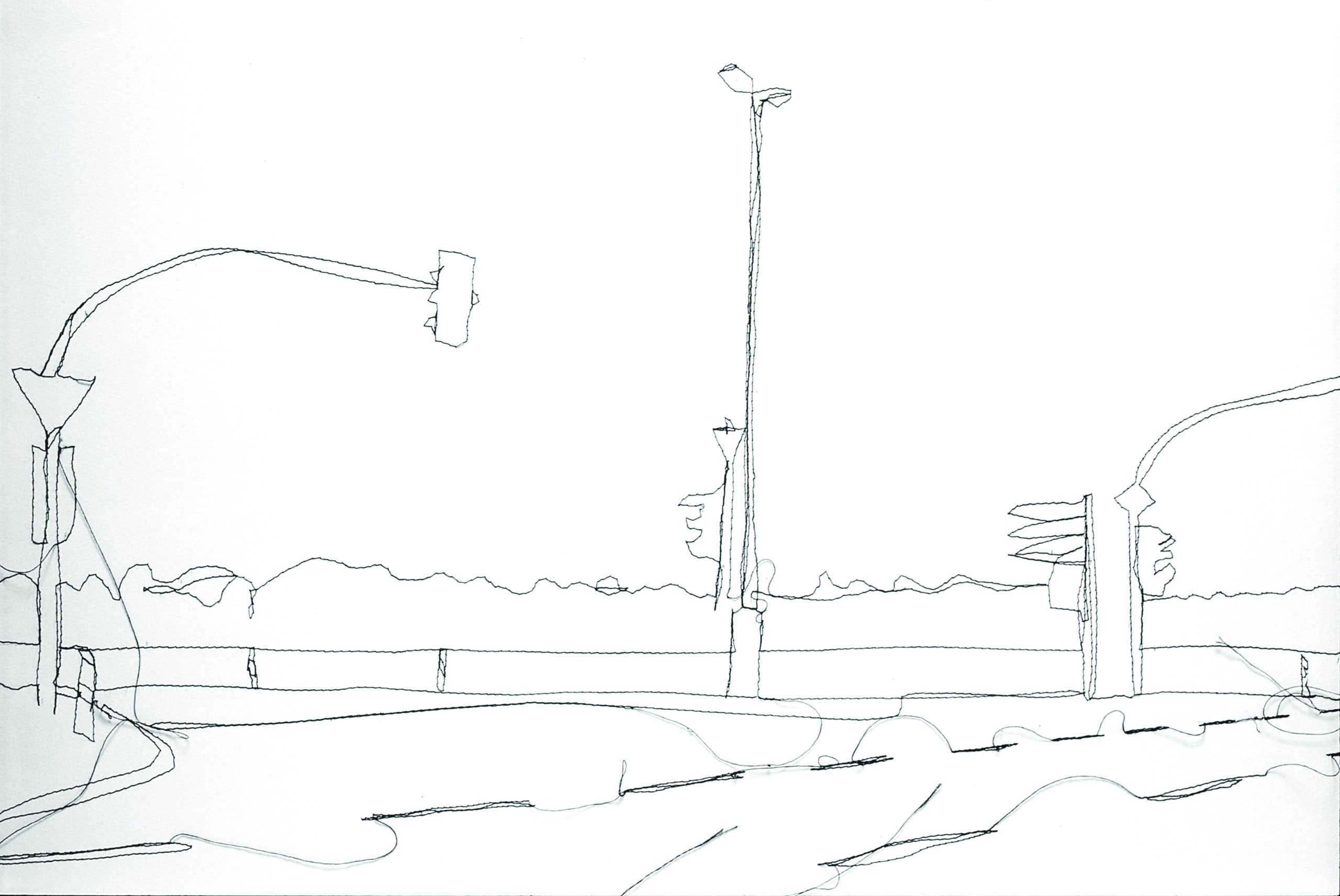

Straße

2003

Sewn drawing, thread, paper

42 x 56 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

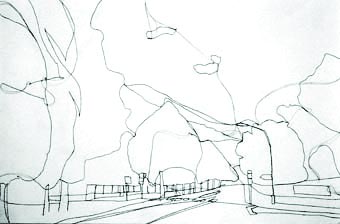

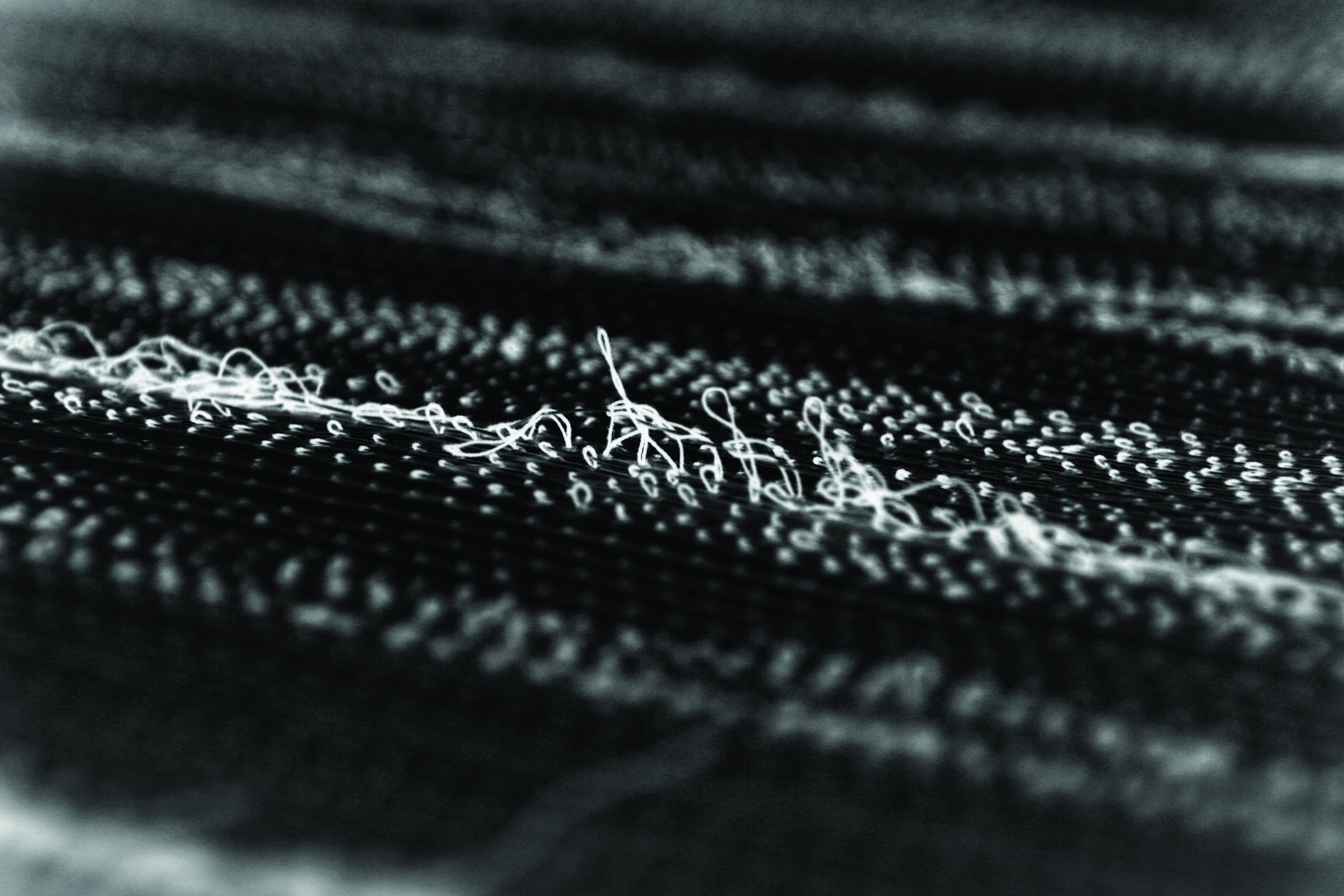

Michaela Melián

Straße

2003

Sewn drawing, thread, paper

42 x 56 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

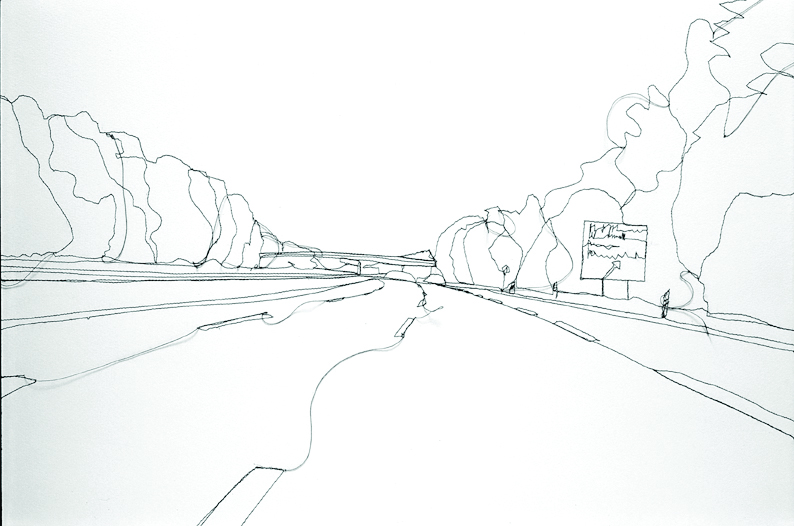

Michaela Melián

Straße

2003

Sewn drawing, thread, paper

42 x 56 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Straße

2003

Sewn drawing, thread, paper

42 x 56 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

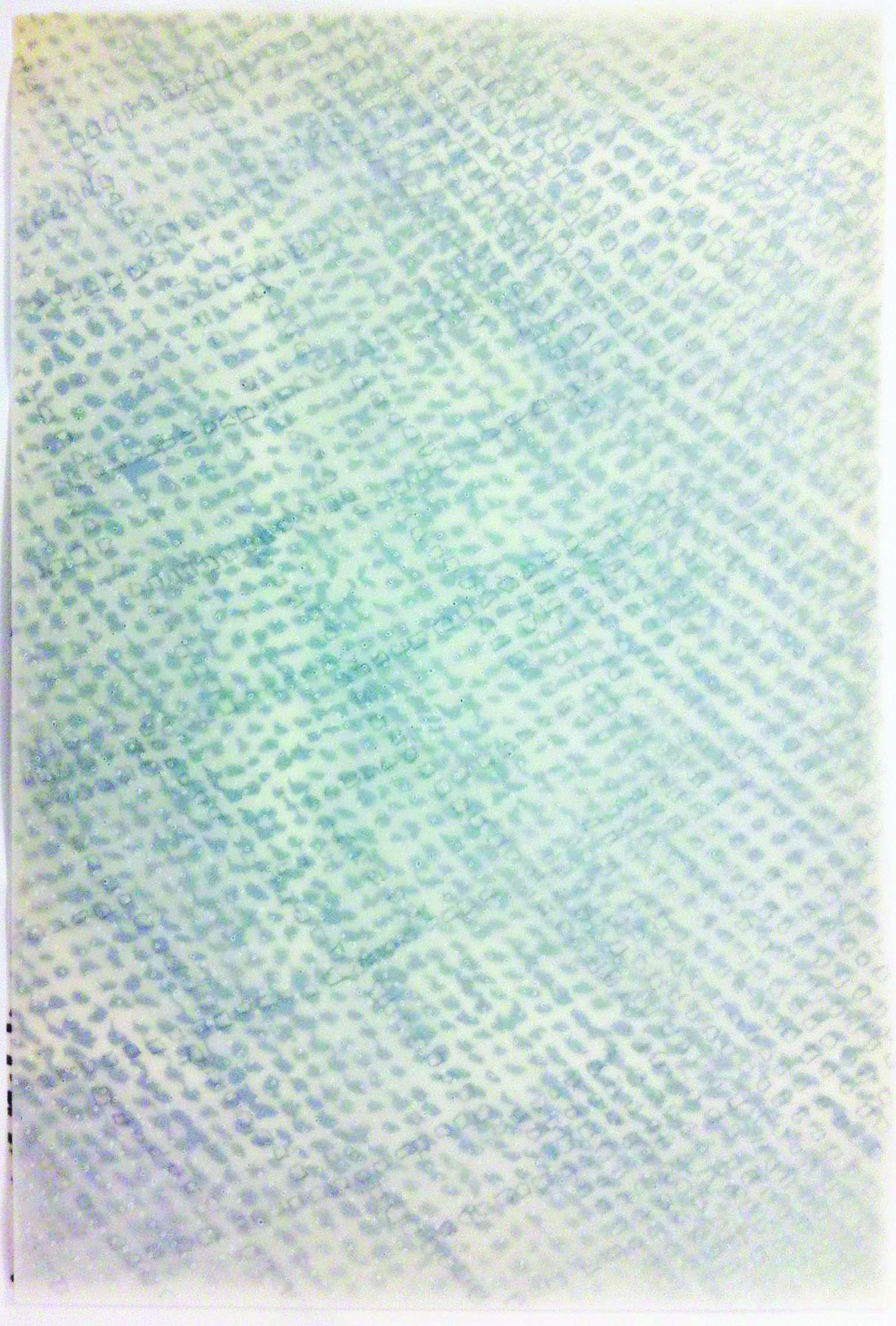

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Three-layered parchment paper

42 x 30 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

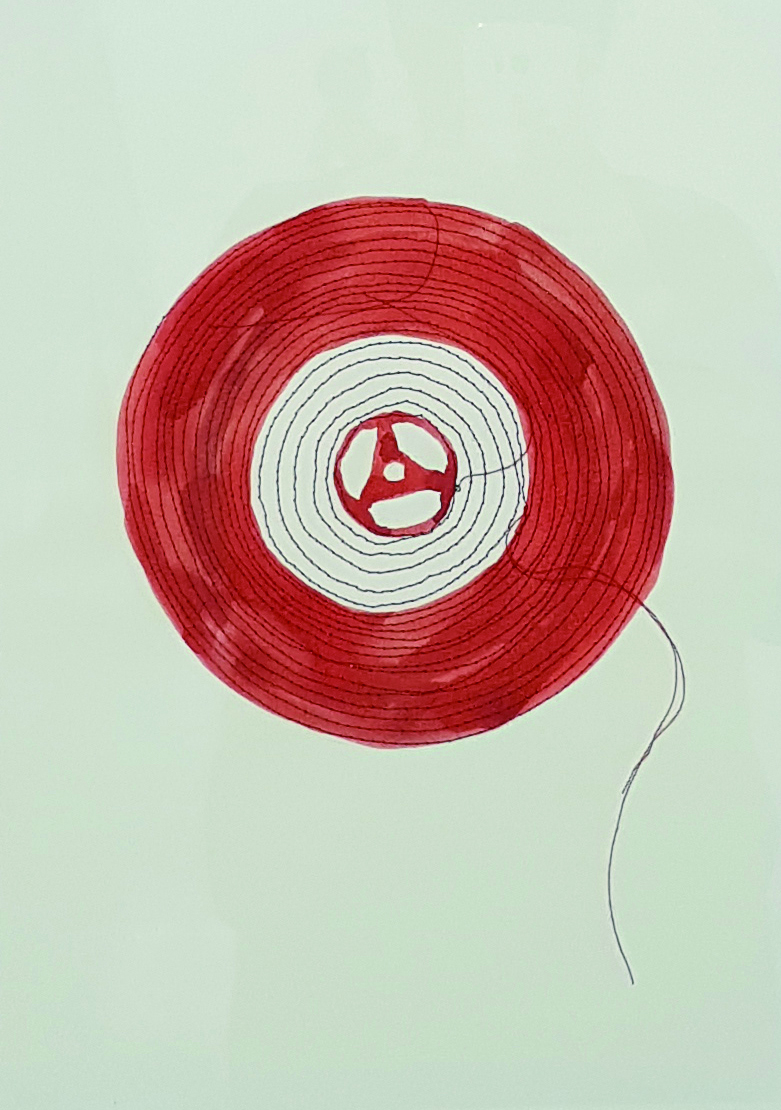

Michaela Melián

Single (Rot)

2013

Ink and thread on paper

36 x 25 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Föhrenwald

2005

Double slide projection with sound, 160 slides + 1 CD (Master), 59:35 mins

Edition of 5

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

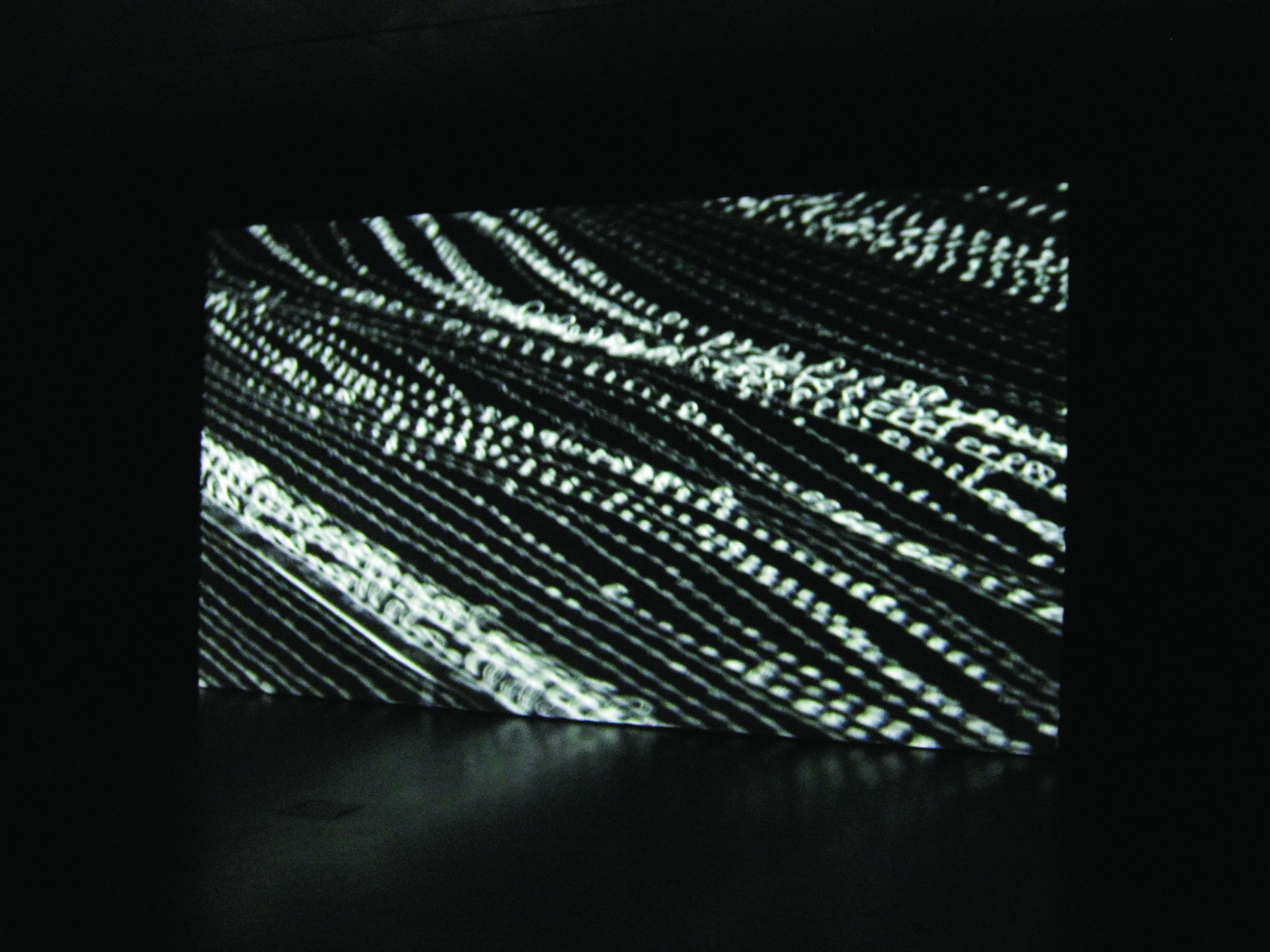

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Still from video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

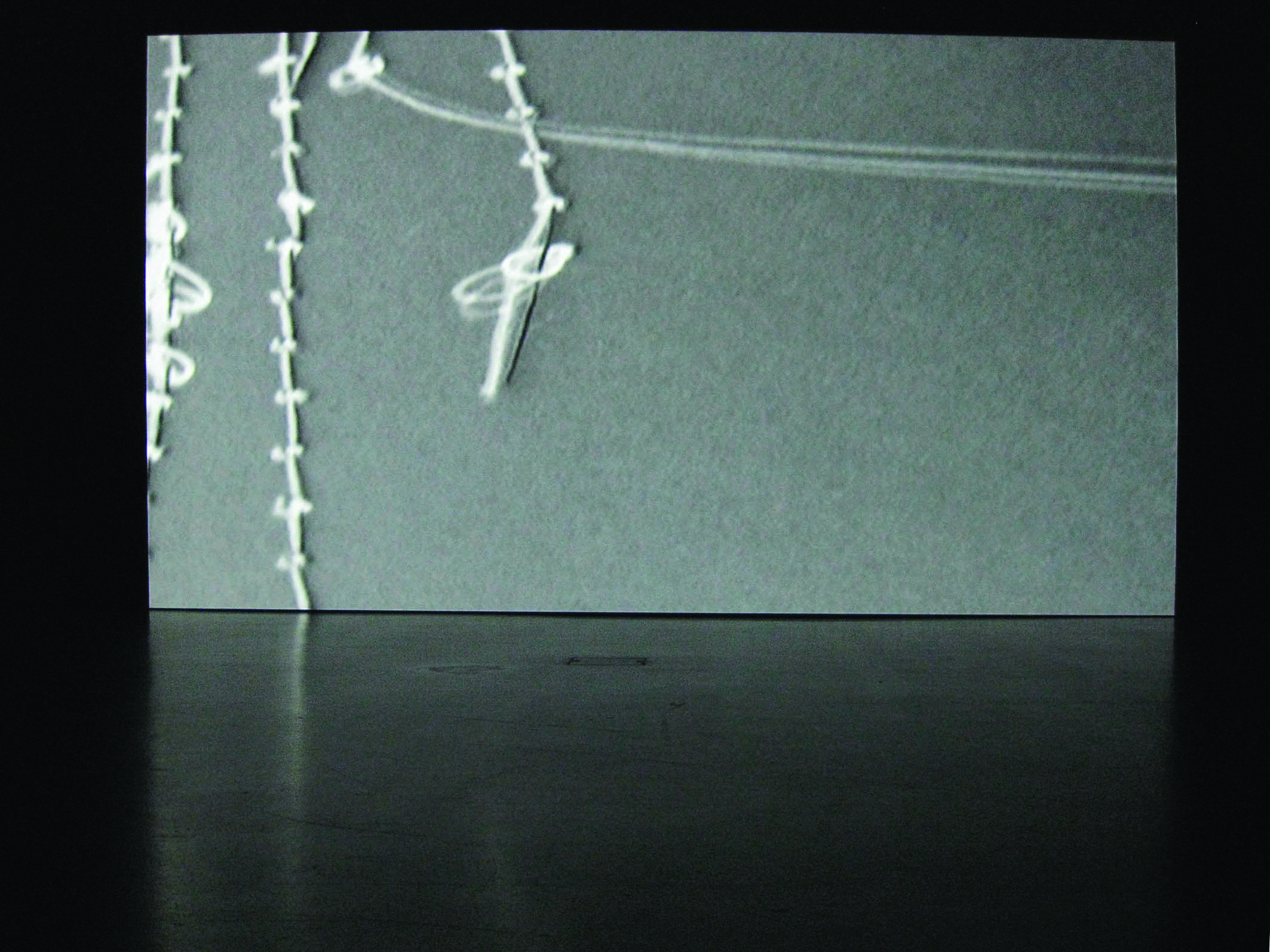

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Still from video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Still from video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Still from video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Installation view at Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, Austria, 2009

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Video and sound installation, DVD, format 4:3, with soundtrack in German/English, 53 mins

Edition of 5

Installation view at Lentos Kunstmuseum Linz, Austria, 2009

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross, Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2014

Thread, paper

56 x 42 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross,

Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2014

Thread, paper

56 x 42 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross,

Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission

Michaela Melián

Speicher

2008

Thread, paper

56 x 42 cm

Photo courtesy of Galerie Barbara Gross,

Munich, and Michaela Melián

Printed with kind permission