After Russia1

Are not dreams in some manner already fictive? Or does the word ‘fictive’ together with ‘dreams’ refocus our attention on the work of art, be it art, poetry, novel or film. Nevertheless, these forms are not involuntary nor the direct result of the unconscious as of dreams. Rather, they are conscious, deliberate acts of creation, the makings of the imagination. This is their great value precisely because they can draw upon history, events, life as much as the imagination. As such, the significance of these artistic forms is to be found in their capacity to create a space for hope, desire and belief. They are the stuff of dreams.

The films of Andrei Tarkovsky did just that. Apart from a small handful of documentaries and books, Tarkovsky made seven feature films before he died at the age of 54 in 1986. His films were Ivan’s Childhood (1962), Andrei Rublev (1966), Solaris (1972), The Mirror (1975), Stalker (1979), Nostalghia (1983) and The Sacrifice (1986). Individually these films are each quite extraordinary. And together, these films, in different ways, explore the concept of ‘fictive dreams.’ They are often times based on true historical events or on novels, shaped in the form of allegories or parables that each are a measure of and reflect on the exigencies of life. Speaking about Andrei Tarkovsky, the film director Ingmar Bergman once reflected:

When film is not a document, it is a dream. That is why Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all. He moves with such naturalness in the room of dreams.

And, Tarkovsky himself wrote in his book Sculpting in Time that:

Faced with the necessity of shooting dreams, we had to decide how to come close to the particular poetry of the dream, how to express it, what means to use…All this material found its way it’s the film straight from life, not through the medium of continuous visual arts.2

Tarkovsky’s films were often categorised as ‘Science Fiction,’ a genre in which fictive imaginings spin off the real. This fictive real suggests a parallel world, a future time or alien presence. Traditionally, this genre, especially in Russia, served as a critique of society, of totalitarian governments and lack of free will, a dystopia in short. We can well remember the novels of Yevgeny Zamyatin (amongst others) we published and banned in the early period of the Soviet Union. Tarkovsky’s films are not based simply on an imagined future. Rather, they weave historical memory and an imagined past, a past out of which the real can be shaped and understood.

Tarkovsky’s first film Ivan’s Childhood (1962) tells the story of 12-year-old orphan boy Ivan and his experiences working for the Soviet army as a scout behind the German lines during World War Two. However, it was his second film Andrei Rublev (1966) that begins to explore more extensively what we are calling the world of the fictive real. Presented3 as a tableau of seven sections in black and white, the film depicts medieval Russia during the first quarter of the 15th century, a period of Mongol-Tartar invasion and growing Christian influence. Commissioned to paint the interior of the Vladimir cathedral, Andrei Rublev leaves the Andronnikov monastery with an entourage of monks and assistants, witnessing in his travels the degradations of his fellow Russians, including pillage, oppression, torture, rape and plague. Faced with the brutalities of the world outside the religious enclave, Rublev’s faith is shaken, prompting him to question the uses or even possibility of art in a degraded world. After Mongols sacked the city of Vladimir, burning the very cathedral that he has been commissioned to paint, Rublev takes a vow of silence and withdraws completely, removing himself to the hermetic confines of the monastery.

The film’s final section concerns a boy named Boriska who convinces a group of travelling bell-makers that his father passed on to him the secret of bell-making. The men take Boriska along, and are quickly enthralled by the boy’s ambition, determination, and confidence that he alone knows how to build the perfect bell. Boriska is soon commanding an army of assistants and peasant workers. Rublev appears; at first standoffish and mistrustful of the boy, he finds himself drawn to Boriska’s courage and unselfconscious desire to create. Moved to put aside his vow of silence, Rublev serves finally as the boy’s confessor, and he finds that, through Boriska, his faith, and art, have been renewed.

The film ends with a montage of Rublev’s painted icons in colour.

It was not until some six years later that he was able to release his third feature film Solaris (1972). The work goes beyond the boundaries of the historical real, uncovering a fictive world whose characters are filled with hope and disenchantment.

Co-written and directed by Tarkovsky, the film was an adaptation of the Polish author Stanislaw Lem’s novel Solaris (1961). Both the novel and film are largely set aboard a space station orbiting a fictional planet ‘Solaris.’ The scientific mission has stalled because the crew of three scientists have each fallen into an emotional crisis. A psychologist is flown out to the space station to evaluate the situation, but finds himself experiencing also the same mysterious phenomena as the crew.4 The planet Solaris is trying to make contact with the crew by reaching into their subconscious and creating living replicas of whatever it finds locked in there. A replica of the psychologist’s wife, who committed suicide years before, appears to him on board the space station and they embark on an intense affair. The replica is an embodiment of his lost love and the residual guilty memory he has of her. Romantic fulfilment becomes an ‘an impossible ideal buried in the past.’

Following Solaris, Tarkovsky made The Mirror (1975), a non-narrative, stream of consciousness, autobiographical film-poem that blends scenes of childhood memory with newsreel footage and contemporary scenes examining the narrator’s relationships with his mother, his ex-wife and his son. The oneiric intensity of the childhood scenes in particular are visually stunning, rhythmically captivating, almost hypnotic.5 Tarkovsky weaves together scenes of nature and mundane everyday life with archival footage of events that have occurred within the narrator’s lifetime, notably The Spanish Civil War, the Sino-German conflict during World War Two and the Atomic Bomb. These two sets of images contrast with one another.

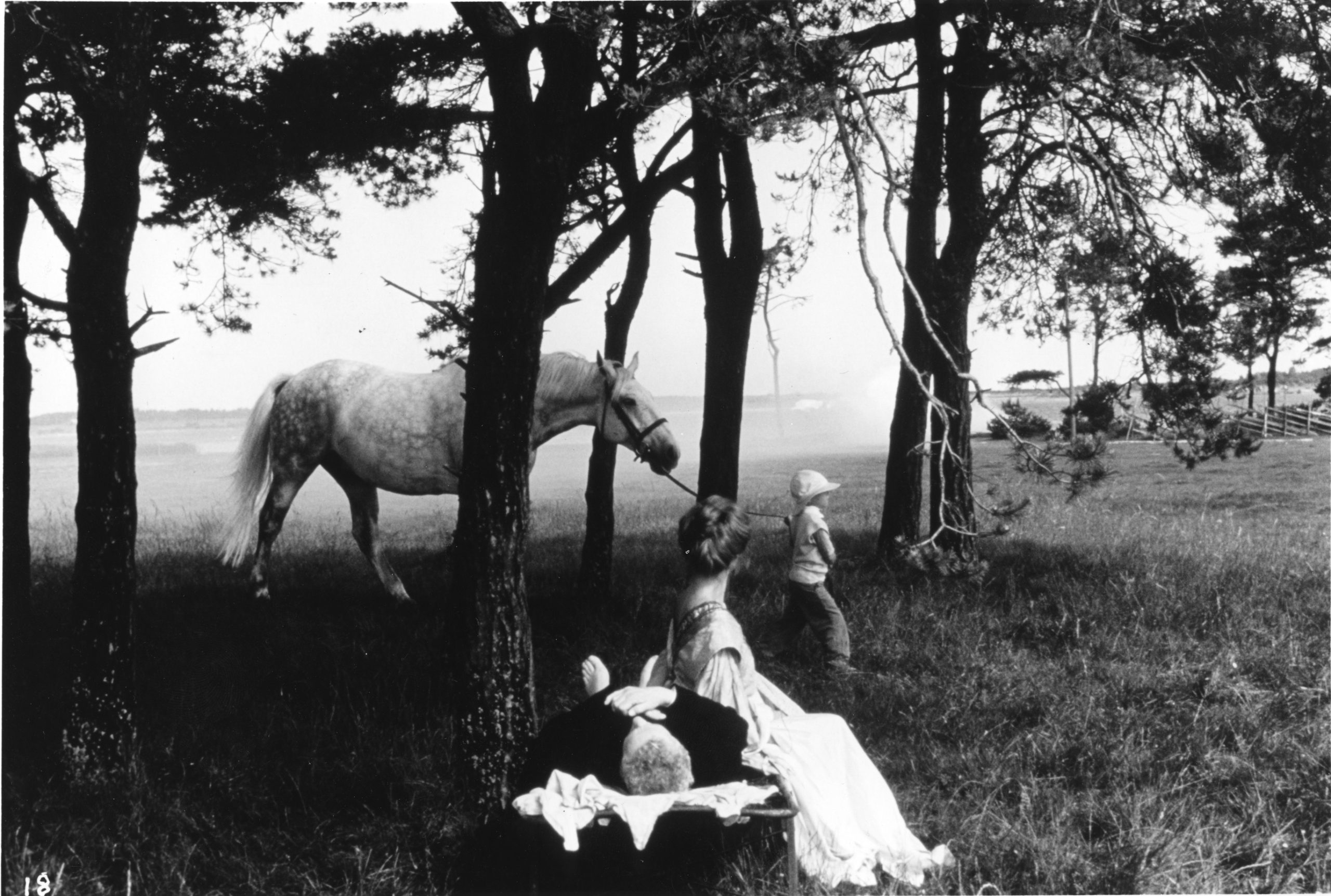

In 1979, Tarkovsky finished Stalker, another adaptation this time from Boris and Arkady Strugatsky’s novel Roadside Picnic. Stalker is far more pessimistic than his previous films. The film follows a Writer and a Scientist, who are guided by a man called the ‘Stalker,’ on a journey through a mysterious wasteland referred to as the “Zone.” The people are exhausted and as worn down as their surroundings. Although the Zone is off-limits to civilians, illegal guides known as ‘Stalkers’ make their living by guiding customers through the Zone to the ‘room.’

The three protagonists have left the confines of a grim, rotting Eastern European city. They walk through a charming-looking rural setting.6 The Zone is lush and green, an organic profusion of growth and chaos which creates a stark contrast to the decaying rigidity of the city. Their goal being to travel to the ‘room,’ at the centre of the Zone, where their innermost desires, wishes and dreams may be fulfilled. To enter the ‘room’ is to be granted one’s deepest unconscious wish.

After much soul-searching, they fail in their quest through a lack of willpower. None of the three men dare enter the ‘room’ and the ‘Stalker’ returns to his distraught wife and daughter, who has been born crippled probably due to her father’s constant exposure to the atmosphere of the ‘Zone.’

The arguments among these men slowly close in around the Stalker’s central concerns: the relationship between hope and reality, the vagaries of human intentions and need for mystery. The Professor seems intent on measuring the forces at work within the Zone. He is, the Writer claims, “putting miracles to an algebra test.” Even the seemingly supernatural granting of wishes, the Professor believes, will leave some physical trace, something which can be measured (or annihilated).7 A disappointed idealist, the Writer expects little good to come of hope. As Nietzsche wrote “Hope: in reality it is the worst of all evils, because it prolongs the torments of Man” (Human All Too Human).

The film was shot near Tallinn. Vladimir Sharun, the film’s sound designer notes:

We were shooting near Tallinn in the area around the small river Piliteh with a half-functioning hydroelectric station. Up the river was a chemical plant and it poured out poisonous liquids downstream. There is even this shot in Stalker: snow falling in the summer and white foam floating down the river. In fact, it was some horrible poison. Many women in our crew got allergic reactions on their faces. Tarkovsky died from cancer of the right bronchial tube. And Tolya Solonitsyn too. That it was all connected to the location shooting for Stalker became clear to me when Larissa Tarkovskaya died from the same illness in Paris…8

Six years after the completion of the film the fourth energy block in Chernobyl exploded and the 30-kilometre Zone became a reality.

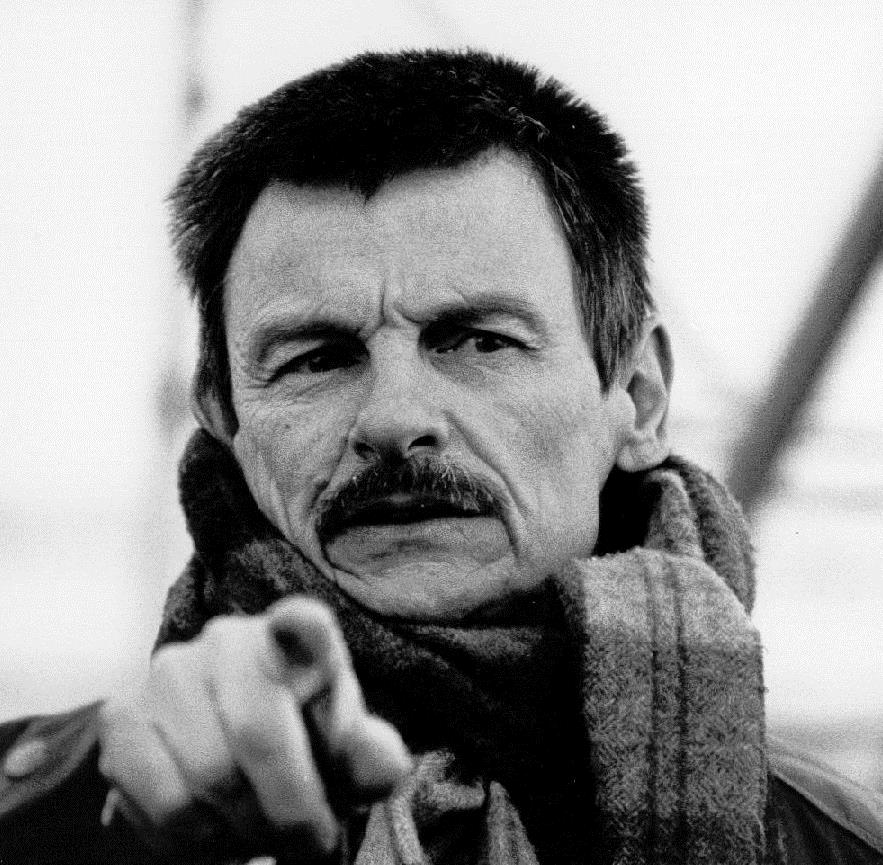

Andrei Tarkovsky.

In Nostalghia (1983) an exiled poet Andrei Gortchakov (Oleg Yankovsky), travels to Italy to research the life of 18th-century Russian composer Pavel Sosnovsky, who lived there and, despite achieving international recognition away from his homeland, eschewed fame and returned to the humble life of a serf, only to sink further into despair and commit suicide. Andrei and his interpreter Eugenia (Domiziana Giordano) have travelled to a convent in the Tuscan countryside, to look at frescoes by Piero della Francesca. Andrei decides at the last minute that he does not want to enter the convent.9

Their visit to the therapeutic hot springs pool of St. Catherine in Bagno Vignoni proves to be the catalyst that spurs Andrei into action. Historically, the hot springs were constructed to alleviate the suffering of the ill. Furthermore, St. Catherine of Siena, after whom the pool was named, was an advocate for the reunification of the Eastern (Orthodox) Church and the Western (Roman Papal) Church during the Great Schism of the Ecumenical Church. Figuratively, Andrei too, is a supplicant to the pool of St. Catherine seeking to heal the sickness within his divided soul. In essence, Andrei’s uneventful biographic research trip has developed into a personal pilgrimage to find his own personal unity.

Eugenia attempts to engage him in a conversation over Arseny Tarkovsky’s (Tarkovsky’s father) poetry but Andrei dismisses his father’s work, reasoning that the simple act of translation loses the nuances of the native language. Eugenia then argues, “How can we get to know each other?” He replies, “By abolishing frontiers between states.” Eugenia is attracted to Andrei and is offended that he will not sleep with her. Andrei feels displaced and longs to go back to Russia. He is haunted by memories of his wife waiting for him. Instilled with a pervasive sense of melancholy, Andrei becomes profoundly alienated from his beautiful companion, his family, his country, and even himself.

And yet, during this visit, Andrei becomes intrigued by the presence of an eccentric old man named Domenico (Erland Josephson), who once imprisoned his family for seven years in an apocalyptic delusion. After asking Eugenia to translate some of the descriptive words used by the villagers to characterise the inscrutable Domenico, Andrei rationalises, “He’s not mad. He has faith,” and asks Eugenia to act as an intermediary. Unable to convince Domenico to grant an interview to Andrei, Eugenia leaves in frustration.

Domenico ultimately accepts the company of the attentive Andrei, and invites him to the abandoned house where he had kept his family in captivity, and who were freed by the local police after seven years. Domenico reflects on the folly of his actions as a desperate and selfish attempt to spare his family from a self-destructive and dying world. He implores Andrei to perform a seemingly innocuous task, to cross the pool of St. Catherine with a lighted candle. This is part of a greater redemptive design, Domenico claiming that when it is finally achieved, he will save the world. Andrei is reluctant to undertake Domenico’s illogical request. Yet he is intrigued and cannot refuse him.

Andrei immerses himself in the solitude of his memories and vague conversations with Domenico. Separated from his family, far from his homeland, and now alone, Andrei slips further into a state of profound isolation and unrequited longing, his own spiritual nostalghia. The two men both share a feeling of alienation from their surroundings.

During a dream-like sequence, Andrei sees himself as Domenico and has visions of his wife, Eugenia and the Madonna as being all one and the same. Andrei thinks of cutting short his research to leave for Russia. But, he gets a call from Eugenia, who wishes to say goodbye. She tells him that she has met Domenico in Rome by chance who had asked if Andrei has walked across the pool as he promised. Andrei says he has, although it is not in fact true. Later, Domenico delivers a speech in the city about the need of mankind of being true brothers and sisters and to return to a simpler way of life. Finally, against the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth symphony playing in the background, Domenico immolates himself.10 The artist and the madman understand each other because they are part of the same person. Andrei, after learning from Domenico about the supposedly spiritually fulfilling task of walking a lit candle across a hot mineral pool. Andrei returns to the mineral pool to fulfil his promise, only to find that the pool has been drained. Nevertheless, he enters the empty pool and repeatedly attempts to walk from one end to the other without letting the candle extinguish. These attempts take in real time over nearly 10 minutes. As he finally achieves his goal, he collapses.11

The powerful last and long shot shows Andrei in the foreground of an ethereal coexistence between the two worlds, as the Russian farmhouse becomes encapsulated within the arching walls of a Roman cathedral. It is both an idealised and an ominous closure, as the muted colours of the Russian landscape now suffuse the Italian streets — a tenuous reunification of the spiritual schism within Andrei’s soul.

It is through long durational scenarios that Tarkovsky manages to elucidate something resembling spirituality. An allegory, Tarkovsky presents the two disparate worlds — the spare, monochromatic landscape of the Russian countryside and the lush, idyllic meadows of rural Italy — that collide within the soul of the Russian author, Andrei. Through the melancholic Andrei, Tarkovsky attempts to reconcile his own feelings of emotional abandonment, loss of cultural identity, alienation, and artistic need.

The abolition of frontiers is a subject explored in Tarkovsky’s earlier films, Solaris (1972) and Stalker (1979). However, while the principal figures in both films coexist in a metaphysical realm between reality and the subconscious, Andrei in Nostalghia (1983) is profoundly aware of his physical separation from his beloved, his distant homeland and it is his innate longing to find unity within himself that unconsciously guides him. Ironically, his actions become antithetical to his own thoughts on the abolition of frontiers, as he creates artificial barriers to isolate himself from his physical reality.

In his book Sculpting in Time, Tarkovsky wrote that he wanted Nostalghia, his first film after leaving Russia to escape censorship, to be “about the particular state of mind which assails Russians who are far from their native land.” Tarkovsky’s personal struggle between love of country and creative freedom inevitably led to his defection to the West in 1983 with his wife, Larissa, leaving behind their son, Andriuschka, in the Soviet Union.

By the time Tarkovsky started work on his next and final film, The Sacrifice (1986), he knew he was seriously ill with cancer. A Swedish production, The Sacrifice is an allegory of self-sacrifice in which Alexander the principal figure, played by Erland Josephson again, gives up everything he holds dear to avert a nuclear catastrophe.

The film opens on the birthday of Alexander. He lives in a beautiful house on a remote island, with his actress wife Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), stepdaughter Marta (Filippa Franzén), and young son, “Little Man,” who is temporarily mute due to a throat operation. Alexander and Little Man plant a tree by the seaside, when Alexander’s friend Otto, a part-time postman, delivers a birthday card to him. When Otto asks, Alexander mentions that his relationship with God is “nonexistent.” After Otto leaves, Adelaide and Victor, a medical doctor and close family friend, who performed Little Man’s operation, arrive at the scene and offer to take Alexander and Little Man home in Victor’s car. However, Alexander prefers to stay behind and talk to his son. In his monologue, Alexander first recounts how he and Adelaide found this lovely house near the sea by accident, and how they fell in love with the house and surroundings, but then enters a bitter tirade against the state of modern man.12

Still from film The Sacrifice (1986) by Andrei Tarkovsky

The family, as well as Victor and Otto, have gathered at Alexander’s house for the celebration. The family maid, Maria, leaves while the nursemaid, Julia, stays to help with the dinner. People comment on Maria’s odd appearances and behaviour. The guests chat inside the house, where Otto reveals that he is a student of paranormal phenomena, a collector of “inexplicable but true incidences.” Just when the dinner is almost ready, the rumbling noise of low-flying jet fighters interrupts them, and soon after, a news programme announces the beginning of what appears to be war and threat of nuclear disaster. In despair, Alexander vows to God to sacrifice all he loves, even their Little Man, to avert disaster of nuclear warfare.

Otto advises him to slip away and be with Maria, whom Otto convinces him is a benign witch. Alexander takes his gun, leaves a note in his room, escapes the house, and rides his bike to where Maria is staying. She is bewildered when he makes his advances, but when he puts his gun to his temple, at which point the jet fighters’ rumblings return, she soothes him and they make love. When he awakes the next morning, in his own bed, everything seems normal. Having followed the doctor’s instructions, the threat seemingly past, Alexander then sets about destroying all traces of his former life, thus fulfilling his private vow. After members of his family and friends leaves for a walk, Alexander, who had stayed back, sets fire to the house. As the group rush back, alarmed by the fire, Alexander confesses that he set the fire himself. Maria appears and Alexander tries to approach her, but is restrained by others. Without explanation, an ambulance appears in the area and two paramedics chase Alexander, who appears to have lost control of himself. Maria begins to bicycle away, but stops halfway to observe Little Man watering the tree he and Alexander planted the day before. As Maria leaves the scene, Little Man, lying at the foot of the tree, speaks his only line, quoting the opening line of the Gospel of St.John “ ‘In the beginning was the Word’… Why is that, Papa?”13 Is he a saint whose sacrifice rescued humanity, we are invited to ask, or is he a madman caught up in messianic delusions?

As with all of Tarkovsky’s films, reality is caught in a state of flux between present/past, memory/perception, reality/fantasy, dream-time/real·time. For Tarkovsky, this movement between inner and outer states is more significant than the abstract rationalism and science for understanding reality. It is captured by the duration of long takes and, as the philosopher Henri Bergson proposed, the understanding of reality through immediate experience and intuition rather than rationalism and science. Moreover, this sensation of time, is not only achieved by the duration of the shots or camera movement, but by the entire mise-en-sc ène. All that is seen and heard within the frame is woven together to complement and augment the rhythm of the scene or shot and establish the temporal flow of the film.

There is a persistent sense in Tarkovsky’s work of an ineffable spirituality within the constant presence of nature, of an ineffable spirituality and the spirit of a fictional real that haunts the present, which are constantly threatening to disappear in today’s world.

Still from film Stalker (1979) by Andrei Tarkovsky