How to escape the end, the dead-end of existence, the ultimate death in both art and life? This has been the definitive question that fuels many dreams of being. In art, death’s inevitability has inspired ideas of transcendence from Gilgamesh’s lamentation on the loss of his friend Enkidu, to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice and beyond. To continue, to linger on, to endure beyond the expected art formats is a guiding principle of a particular kind of performance art. Following music’s transcendental nature and its possibility to linger on in our consciousness, performance art deals with the tasks of expanding the time limits of a viewing experience. Speaking in general terms, this is yet another stage in humanity’s dream of continuity. As an illustration, I think of the example of Marina Abramović’s art practice and her Marina Abramović Institute’s endeavour.

Abramović’s oeuvre has never shied away from the transcendental and the manifestly tragic, in its reliance on the power and ethos of myth. The romanticism of myth is complicated by its metaphorical association to the tragic premise of death or loss or ending. The symbolic core of her practice is organised around and propelled by its dialectical opposition to limitations – ideological, spatial and in relation to time. Her most daring oppositional works challenged and subverted – via artist’s body as a medium – ideological restrictions (the famous works dealing with the communist ideological symbol embodied in the five-point star). But even her earliest works had the tendency of speaking not only to human construction of power, but going against elemental and primal limitations — that of space and time. It is in this light that I tend to see her early work, Freeing the Horizon of 1973.

Abramović’s early explorations comprise of post-object installations and sound environments in which she recognised their transformational potential for viewers. One of her first sound environments, although unrealised, was The Bridge (1971), an actual bridge with loudspeakers installed on it, that would emit the sound of the bridge collapsing. The audience, on the bridge, would experience a sensory representation of its disappearance, and ultimately contemplate the abrupt ending of an existence. However, this scenario of destruction is meant to do precisely the opposite – to go beyond the death of the material – and it led to her other works inspired by the transcendental dimension in art.

The similar transformative urge inspired her photographic works such as Freeing the Horizon, in which she manipulated cityscapes in order to delete buildings and let the sky behind them become visible. This strategy of freeing the imaginative realm in the tissue of the real has become her signature and a lesson she shared with the generations of performers dedicated to actions that are different in manifestations, styles and scopes but share a similar propensity, which is, to free the clogged, overburdened horizon line and let the emptiness allow the viewer to go beyond – in both spatial and time dimensions. Most recently, the artists associated with the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI) have reiterated this specific transformative viewing, and, as I would argue, show many possibilities of freeing the horizon.

MAI partnered with non-profit organisation NEON to present a performative exhibition titled As One at Benaki Contemporary Museum in Athens, with newly commissioned performance pieces by Greek artists, and other public participatory events such as workshops and lectures on the Marina Abramović method. NEON, which means “new” in Greek, is founded by Dimitris Daskalopoulos, an art collector. As One took place in March and April of 2016, and was described as the largest and most ambitious project dedicated to performance art in Greece to date. Offering long-duration performance, As One aimed to reach out to and inspire the Greek public.

From an open call that drew 320 people, MAI and NEON chose 24 young Greek performance artists of varying disciplines – six who do long-duration works and others who perform for shorter periods. These artists engaged in a range of long-duration performances for eight hours a day, for seven weeks, in this marathon event that boasted more than 22,000 visitors.

Through the intensity of the performances and their explorations of time, fear, entrapment, discomfort and control, the works offered an abstract reference to the contemporary political environment: it corresponded with the emotions of anguish that plagued the economically-troubled country. It is interesting to note that the general artistic striving to free the horizon is provoked by the actual existential crisis of this European nation. It situates art within the realm of everyday action without making it manifestly political in its content. The art practices are thus rooted in resistance to all limitations. It thematises the questions of artists’ active engagement in their immediate reality (and consequently engaging their audiences) by not having an explicit political message – their involvement is decidedly opposed to escapism.

Does this make them fiction and dream-like? It is up to the viewers to gauge their fictive involvement in order to move beyond reality toward an ending. The actions remind us of the lessons of the 1960s – that dreams can be revolutionary, in their radical imaginative potential. We would like to think that these practices hold the promise of freedom beyond another capitalist reiteration of packaging it as a consumable commodity. Passionately believing in the dream that horizons can be freed, the following six artists engaged in long-duration performances, an artistic medium that overturns the conventions of showing only finished works in the gallery and pander to other museum-going clichés, as time, a fundamental element in performance, changes each and every viewer’s experience of the pieces.

In her 324-hour long-duration performance Corner Time, Despina Zacharopoulou, who is based in London and Athens, binds and unbinds herself with rope and carries out a series of actions and rituals. The goal of her performance is to explore the mental spaces that open up during ‘control-exchange’ situations in human relationships. Over the course of seven weeks, for eight hours per day, the artist hosted the audience in an enclosed space, and performed a set of actions combining methods and goals drawn from practices of meditation, discipline and restriction. The goal of this piece was to create potent, experimental situations of ‘control-exchange’ while playing with the multiple functions of the gaze: a mechanism for introspection, surveillance, recognition and communication.

Thodoris Trampas interpreted the task of “dwelling in time” to meditate on nature and creation, division and composition in his performance titled Pangaia. Trampas delineated a process of union through destruction, and the need for reconciliation with the other side. In an enclosed space, six metres by seven, for seven weeks (and eight hours each day), the body is set against the material world – a large piece of rock – in order to create its replica in plaster. This copying, this repetition, is a way of experiencing the existence of nature from scratch. Smashing the rock differentiates the copy from the original, and the resulting fragments accumulate and change the mass of the material — transform it, give it new form.

In White Cave, an allegory of Plato’s Cave, dancer and a performance artist Nancy Stamatopoulou directs her own “spiritual confinement” within a constructed ‘reality’ composed of everyday actions and everyday objects. During the course of seven weeks, the artist remained within a narrow area, which limits were set by the sights of a camera lens, confined inside her own personal “cave” in a shadowy re-enactment of a personal truth. Time passes slowly, like the movement of a turtle. Actions are repetitive, like a punishment. Reality becomes imperceptible, the possibility of escape remote. While the artist is enclosed in a tiny white box, monitors show recordings of the previous week’s performance. The artist wanted visitors to examine the ways they are trapped in their own lives, only to prompt the breakdown of the illusory limitation — the aforementioned freeing of the horizon.

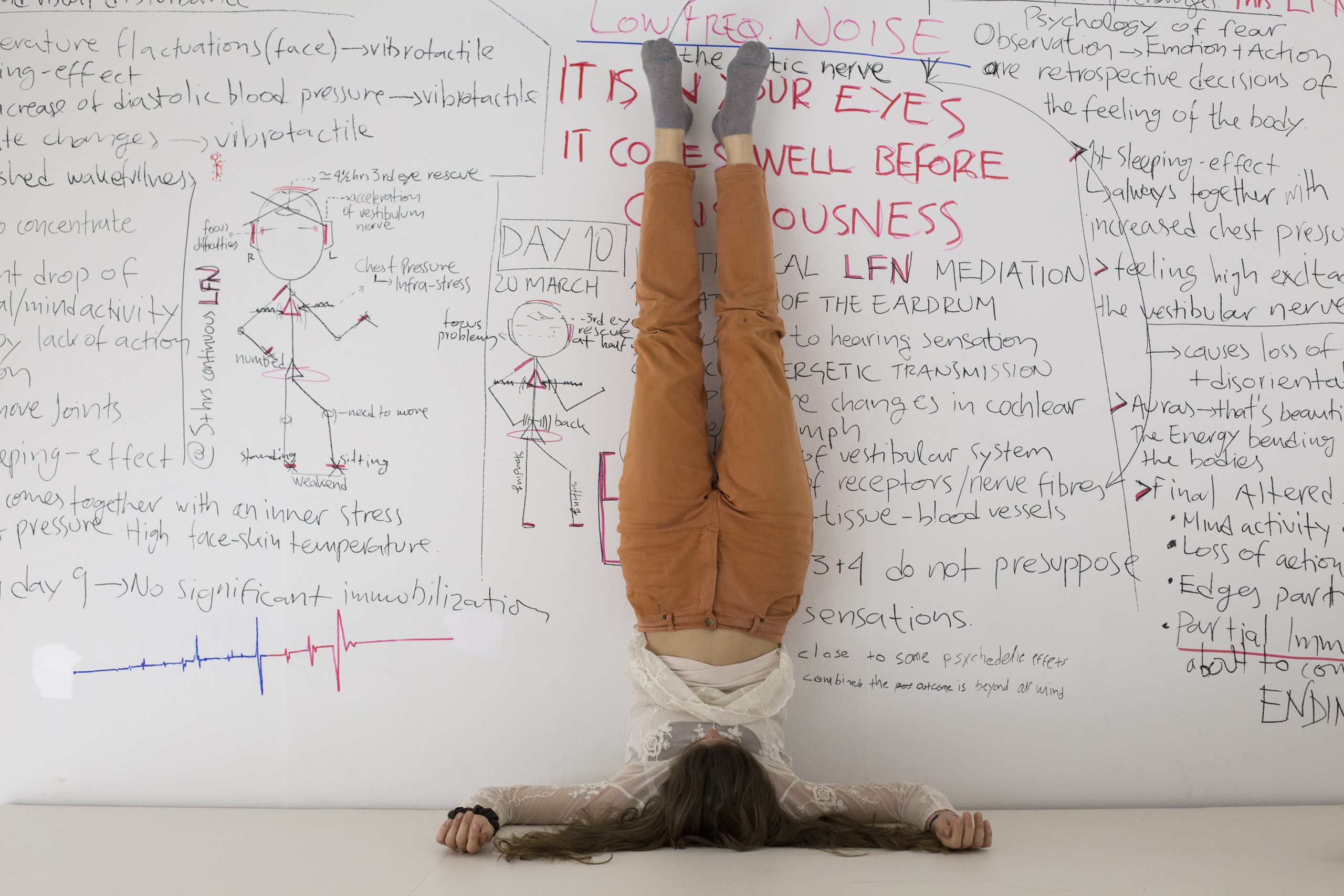

Lambros Pigounis is a sound artist who specialises in the field of contemporary, classical and electroacoustic composition. His long-duration work titled Micropolitics of Noise was driven by his research in acoustic ecology in relation to the human body. The artist was attempting to give physical form to the micropolitics of sound-signalling threats and to demonstrate ways in which noise can be used as a form of violence, while also shaping the soundscape of the future. In the work, he created a long-durational situation in which his body is exposed to subsonic vibrational forces, triggered by the presence of people around him. Left in a state of constant threat for seven weeks, the body unconsciously experiences three kinds of fear-induced reactions: fight — flight — freeze. Pigounis drew on military research in the use of sound as a nonlethal weapon to destabilise populations in conflict situations. He spent eight hours a day on a sloped platform under which speakers rumble while his body experienced impulses of conflict, escape, immobilisation. The artist also noted that the audience showed empathic responses of fear and overcoming it. The effects on his body included nausea, chest constriction, loss of mental capacity, proving how the work can be ultimately transformative for the artist and audience alike.

The long-duration piece Jargon (2016) by Virginia Mastrogiannaki, is the performance in which audience sees Mastrogiannaki counting seconds for eight hours a day for the seven weeks. A human clock measures time as it passes, as it tests the limits of body and mind. Mastrogiannaki renders her own body an analogue machine, a tool for calculating time, the hours we work, the time of the space in which she finds herself. Her mind battles to remain focused on every minute, eight hours a day, for seven weeks, and the piece itself changed dramatically for the artist as time progressed. This is an ascetic act that nevertheless links her with others through the overlay of time and place. The inability of the mind to follow the passage of time means mistakes are unavoidable, but notes taken on paper restore the spirit to the task at hand.

One Person at a Time (2016) by Yota Argyropoulou, one of most popular works, comprises two identical rooms divided by a sheet of glass, one inhabited by the artist and the other by any person who decides to enter the space. The artist then mimics or interacts with the person who comes into the space until they leave. This work showed the most pronounced range of responses as it progresses, because it cannot be controlled: sometimes the outcome is not great because the visitor may be tense, and at other times, the artist achieved a wonderful unity with the visitor. One Person at a Time explores two sides of a “mirror” – what is real and what is a construct. Argyropoulou enters into a fictional world of emotional experience and invites visitors to follow her into action and inaction, detachment and connection. For eight hours each day and for seven weeks, one room will be her own ‘truth’, where time is suspended, a place of privacy ‘shattered’ by the arrival of the real: the visitor in the other room. The glass between them isolates but at the same time invites communication – a possibility of the freeing of horizon performed a quattro mani.

These performances ranged from the endearing to the borderline terrifying, and all artists pushed themselves both physically and mentally, as Abramović herself has done throughout her career. The artist herself had an important lesson to share with the younger performers – how to retain their faculties when pushing themselves to such lengths. MAI is a place where one can develop his or her practice through processes of dreaming, which can ultimately transform perceived reality and continue above and beyond the ending — a new chapter in art’s pursuit of the eternal (ars longa, vita brevis). These examples passionately and affirmatively answer the age-old question: can art be both transcendental and revolutionary at the same time?

Photographs Courtesy of Marina Abramović Institute (MAI)

Yota Argyropoulou | Natalia Tsoukala

One Person at a Time, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Marina Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Natalia Tsoukala.

Thodoris Trampas | Natalia Tsoukala

Pangaia, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Marina Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Natalia Tsoukala.

Lambros Pigounis | Natalia Tsoukala

Micropolitics of Noise, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Marina Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Natalia Tsoukala.

Despina Zacharopoulou | Natalia Tsoukala

Corner Time, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Natalia Tsoukala.

Panos Kokkinias

Communal Moment, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Marina Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Panos Kokkinias.

Amanda Coogan | Natalia ¬Tsoukala

You don’t push a river, 2016

Commissioned and produced originally by NEON + Marina Abramović Institute, on the occasion of AS ONE,

Benaki Museum, Athens, 10 Mar-24 Apr 2016.

Photography by Natalia Tsoukala.