Figure 1. Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1782

Introduction: Artists as Lucid Dreamers

Dreams are one thing everyone has in common. As Jack Kerouac put it: “All human beings are also dream beings. Dreaming ties all mankind together.” Martin Luther King had one – perhaps a more iconic one than you and I — but we all have them. Artists of all disciplines have explored them for millennia, depicting ‘fictive’ dreams far more visionary, startling and disturbing than everyday reality. That, of course, is their appeal.

“A book is a dream that you hold in your hands,” wrote Neil Gaiman, and dreams themselves have been a running theme in literature for centuries, from Shakespeare’s insight that we are made of the very “stuff” of them, to Edgar Allan Poe’s insistence that: “All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.” Jorge Luis Borges wrote of our sadness when being awoken abruptly from a dream, feeling robbed “of an inconceivable gift, so intimate it is only knowable in a trance.” Poets have feared them – Samuel Taylor Coleridge frequently woke his whole household up with his screams – and eulogised them, W.B. Yeats implored a lover not to tread on his, and John Keats declared that: “We need men who can dream of things that never were.”

In the history of Fine Art, dreams have both inspired – like the Byzantine depictions of Jacob’s Biblical dream of an angel-filled ladder bridging heaven and earth — and elicited fear, as in the hellish 15th century nightmares of Hieronymus Bosch, or Henry Fuseli’s demonic goblin incubus sitting on the stomach of a defenseless, sleeping woman (The Nightmare, 1782) (Figure 1). Vincent Van Gogh believed that “I dream my painting and I paint my dream,” and visions of reverie reached their aesthetic and conceptual heights in the simultaneously beautiful and sinister dreamscapes of the surrealists Salvador Dali, René Magritte, Dorothea Tanning, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington and Paul Delvaux.

Susan Hiller’s Dream Mapping (1973) involved seven dreamers sleeping for three nights in a field in England, lying within so-called “fairy rings” — a natural phenomenon where a certain genus of mushrooms sprouts up in a large circle. The next morning, each of their dreams was drawn in map form on a piece of transparent paper, and these were sandwiched together into ‘collective dream maps’ for each night. In the 1990s, artist Bruce Gilchrist and programmer Jonny Bradley created DreamEngine software that monitored the real-time EEG data of the brainwave activity of sleeping subjects, and converted it into art. Outputs included 3D plastic sculptural forms; performances where the neural dream activity triggered projections of multiple pre-recorded video clips around a space; and musical notion for a string quartet who sight-read and played the music in real-time.

Dreams inspired many of my creative heroes, including the great literary surrealist George Bataille and theatre visionary Antonin Artaud. “I abandon myself to the fever of dreams,” Artaud wrote, “in search for new laws.” But perhaps most artists are fictive, lucid dreamers who abandon themselves feverishly – communing with other worlds, connecting with the subconscious, drowning in imagery, and reaching out into the ether. As Lucy Powell has noted: “Like a dream, art both is and isn’t true. Both offer a challenge to the tyranny of realism, replacing what is with what might be. Both generate an altered state of consciousness removed from the humdrum – and both lend themselves to interpretation.”

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) catalysed a fervent dream-fever and new zeitgeist of the psyche as the 19th century turned into the 20th, opening up bold (and contested) new theories of “wish fulfillment” – even our nightmares are our secret wishes, he argued – and the symbolism of the unconscious. Mixing winning ingredients of angst, sex and horror, it was an instant bestseller; Freud later noted that: “insight such as this falls to one’s lot but once in a lifetime.”

Dreams, Angst, Sex and Horror

Dreams, angst, sex and horror have always been prevalent themes in my practice as a multimedia performance artist. In the mid-1970s, I saw a multimedia theatre adaptation of August Strindberg’s A Dream Play by the Welsh theatre company, Moving Being. It stunningly combined live actors with a cinema narrative playing behind them, and it changed my life. I became an experimentalist in multimedia performance, and a researcher into the history of onstage media projections.

Watching A Dream Play, it occurred to me that combining theatre and film could enable a unique form of lucid dreaming where conscious and subconscious could collide and converge. Since then, I’ve worked on projects that explore and enact that fusion in different ways.

There was a period around that time when I could readily induce lucid dreams, although it wasn’t long before I lost the knack. Lucid dreams are all about living the dream, but half here and half there, half asleep, half awake, half you, half someone else. They are willful, directing one’s own experience and fate in the dream world. Lucid dreaming is always on the edge, on the limen, hoping not to awaken, not to fall from the blissful flight taken, from the precipitous edge of the cliff, from the power of being, for that fictive moment, God (or the Devil).

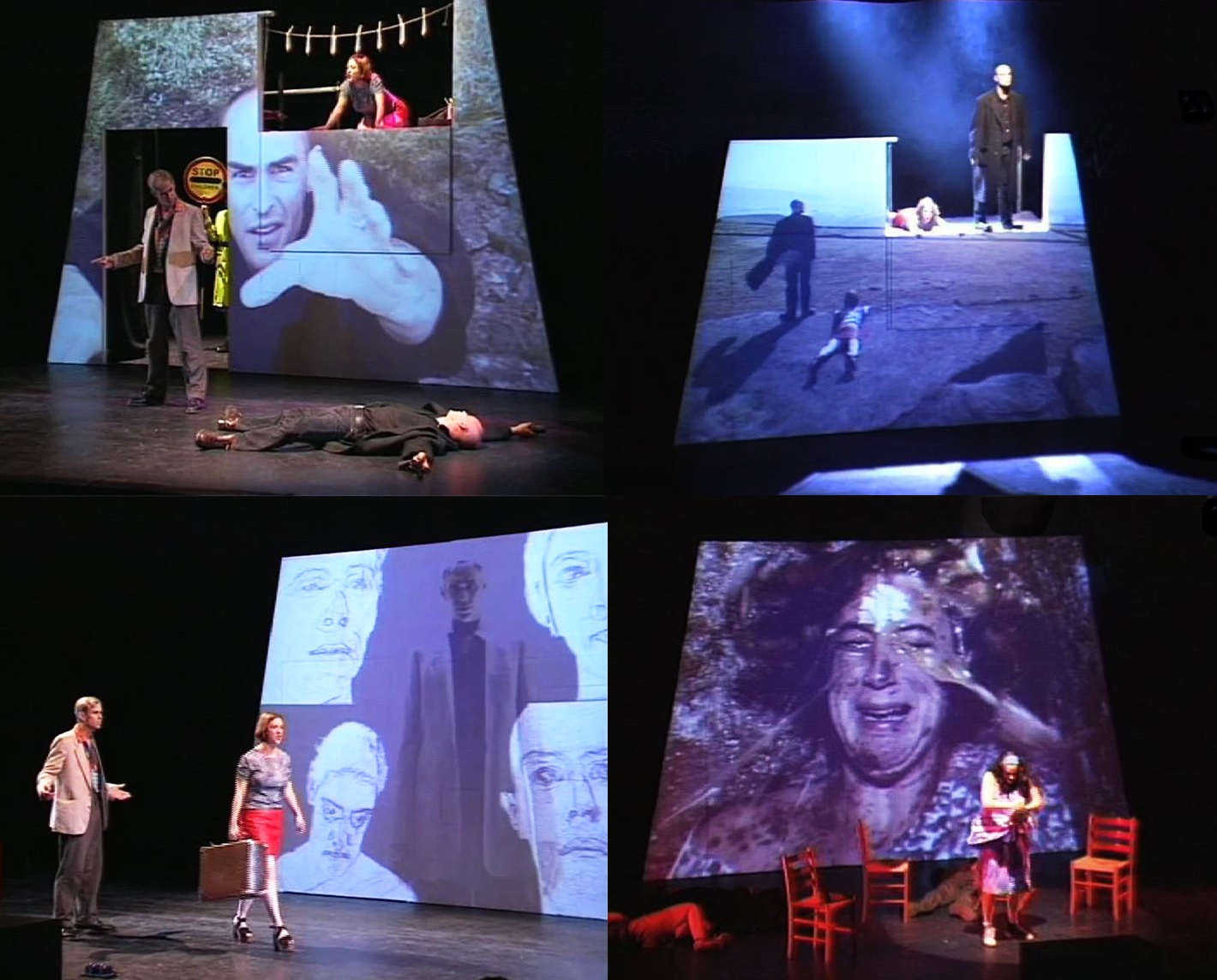

In 1994, I established a multimedia theatre company, The Chameleons Group, to create elaborate lucid dream plays, most recently a one-man interpretation of T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, performed in Chicago, USA in March 2016 (Figure 2). The Chameleons Group performances are presented primarily on theatre stages, but also in gallery settings, and in interactive online environments, such as for Net Congestion (2000), where chat-room audience members were invited to co-write and direct live (streamed) improvised performances in real time (Figure 3). The work generally fuses live performers with projected video imagery – often footage of the same characters, who talk and interact with ‘themselves’ onstage, operating as (invariably darker) doubles, dopplegängers and alter egos, for example, in The Doors of Serenity (2002) (Figure 4).

Figure 2. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, 2013-16

Figure 3. Net Congestion, 2000

As its title suggests, our second production, In Dreamtime (1996), was conceived explicitly as a dream play, and the documenting of each of the four performer’s actual dreams over a three-month period prior to rehearsals served as the core source material for the devising and scripting process. Many video sequences for the show were literal reconstructions, or refined interpretations of the performers’ visions and narratives experienced during sleep. The bottom right image in Figure 4 is one example, where actor Julia Wilson’s dream of being pelted with eggs and blasted by a powerful water-hose was reenacted vividly, while onstage, Wendy Reed simultaneously punches a voodoo doll. The live theatre action for In Dreamtime was played both in front of a four metre-high wooden projection screen, and also ‘inside’ it: the design incorporating four hidden doors and windows, which opened to reveal live action behind, creating an effect of theatre within a movie screen (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The Doors of Serenity, 2002

Figure 5. In Dreamtime, 1996

The show’s narrative revolved around the entanglement of four characters that all experience the same dream. They are manipulated by ‘The Dream Junkie,’ a malevolent spirit hovering between the physical world and the astral plane, who preys upon unwary dreamers. He is ultimately overpowered and killed by one of the rebellious dreamers.

The work has been deeply influenced by the visionary theoretical writings of Antonin Artaud, and my first ever stated research objective was “to update Artaud for the digital age.” In The Theatre and Its Double (1938) – a rare first edition of which I own and cherish, and which emits (at least for me) a spookily powerful aura — he conceives a theatre of cruelty and famously declares that: “actors should be like martyrs burned alive, still signalling through the flames.” Artaud was a key figure within the French Surrealist movement, and was appointed by André Breton as ‘Director of the Surrealist Bureau of Investigations’ in 1925, although they would later quarrel and Artaud would leave the movement, objecting to its increasing politicisation and alignment with communism.

Automatic Dreaming

In The Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), Breton eulogises the surrealist technique of automatism and automatic writing. We have made extensive use of this in the devising and scripting of The Chameleons Group performances, with the resulting material used unabridged, or edited and combined with dialogue created through improvisation. Though its use nowadays is quite rare, we find the automatic writing technique to be highly effective, creating, as Breton has put it: “a considerable assortment of images of a quality such as we should never have been able to obtain in the normal way of writing.” The surrealists essentially inherited automatism from psychics and spiritualist mediums, but as Patrick Waldberg has pointed out, here the message transmitted is sent “not from the spiritual hereafter, but from the actual self hidden by consciousness.”

It is thus akin to dreaming, and in preparation, you empty your mind and put yourself in an open, meditative state, and then start writing as quickly as possible, never pausing for even a millisecond until it’s over. The idea is not to personally write, but as if in a dream to let the unconscious take over, and to spew forth a relentless cascade of words, whatever they may be, without ever interfering or trying to control the stream of consciousness. It is, in Breton’s words: “Thought’s dictation, free from any control by the reason, independent of any aesthetic or moral preoccupation.”

The difference between its use by the surrealists and our methodology is that prior to the writing, the actors go into character and try to allow the character’s subconscious to speak, thus combining surrealist theories of dream and the unconscious with traditional Stanislavskian acting practices. These experiments are thus concerned with the articulation of the unconsciousness of a character, mediated through the unconsciousness of an actor, which is finally ‘made conscious’ in performance.

The results are often startling and dramatic. The writing often has a highly confessional feel, a visual and visceral quality, and conjures images that veer from the visionary to the violent. The scripts frequently contain short and repetitive rhythmical patterns, and are quintessentially ‘dreamlike.’ The In Dreamtime text below by Wendy Reed is a typical example, and was taken verbatim from an automatic writing session, with only the punctuation added later:

Figure 6. Unheimlich, 2005-6

Figure 7. Unheimlich, 2005-6

The Lollipop Lady: I’m not worthy. What is me? There are bruises and I am not worthy. Only of being slashed. Beware of the sheep within. They’re here and you must die. They’re here. The creatures from the shit-pit. The vegetables and deranged minds. The special children. The vandals. The peanut-butter conspiracy revisited. The seeds of discord. The unnatural act. The wrist slashers. The window jumpers. The corpse eaters. Bingo callers. Sheck ‘em up! Giant slugs. Lepers. Keyhole peepers. Die. Die. Die. Die!

In Unheimlich (2005-6), a collaboration with Paul Sermon, Andrea Zapp and Mathias Fuchs, the dream was ‘extra-lucid.’ Two female Chameleons Group performers worked in a blue-screen space in London and were connected with audience participants in the USA, through a sophisticated videoconferencing system. Using chromakey and video-mixing techniques, on the screens surrounding both spaces, the two sets of participants appeared to be visually conjoined and immersed in virtual backgrounds. They were thus able to see and converse with one another within a shared screen space, to virtually shake hands, and to ‘telematically embrace’ (Figure 6).

These intimate interactions were strange and uncanny (the meaning of the German word Unheimlich, and the title of Freud’s book on the subject), and although they were separated by thousands of miles and several time zones, the telepresence of the bodies ‘on the other side’ was intensely felt, and the sensation of physical closeness and virtual touch was extraordinary. The dramatic interactions between the remote actors and their audiences revolved around fantastical journeys through continually changing background rooms and landscapes, from deserts to polar icecaps, and from 3D game worlds to the fires of hell, with the part-physical, part-virtual mise-en-scène catalysing a vividly ‘telepresent lucid dream’ (Figure 7).

The Mobile Phone as Lucid Dream Machine

Realising the ‘dream of telepresence’ is the most significant cultural development of our age. Distance has collapsed, the so-called real and virtual have converged (or more accurately, the virtual has now been incorporated into the real), and understandings and experiences of presence have been utterly transformed. In my youth, the notion of a videophone conversation was one of the wildest and most alluring of all futuristic science-fiction fantasies. Its Skype and FaceTime reality, indeed ubiquity, today has produced an astounding new form of magic — and we should never forget that ‘digital technologies are a form of magic’ — which we barely give a thought.

The mobile phone has become a ‘lucid dream machine’ where friends and families unite, and where lovers meet, become enchanted and live out their dreams, suspended in space-time, floating together in a different world. ‘Lucid dreams have become synonymous with interactive screens.’

Yet while there may be vibrant interactions and beautiful romances taking place via or within the ‘mobile phone lucid-dream-machine,’ like all forms of magic, it has its darker side. For decades, many of the world’s leading theorists, philosophers and even technologists have been soothsayers warning of the potentially catastrophic social and psychological effects of our willing seduction (or rape) by technology. They include the father of cybernetics Norbert Wiener, who as early as 1954 cautioned that: “We cannot worship the gadget and sacrifice the human being to it”; while a year earlier Martin Heidegger had described human beings as “slaves” already “chained to technology.”

In 1964, Marshall McLuhan emphasised that “technologies are self-amputations”, and later warned of “discarnate” societies detached from reality and therefore any sense of responsibility for it, leaving “whole populations without personal or community values.” In 1981, the most nihilist techno-soothsayer of all, Jean Baudrillard made a pronouncement that “there is no real”; while in the 1990s Paul Virilio was describing a terminal society, and Arthur Kroker offered one of the most searing critiques of all, with a book and title announcing The Possessed Individual (1992). Stephen Hawking has since added his computer-assisted voice to the throng, offering another perspective: “the danger is real that [computer] intelligence will develop and take over the world.”

I fear that our newest dream phenomenon, the mobile phone, which formerly used to simply connect voices, may have since become a dark spectre: ‘a dystopian dream machine for a dysfunctional society.’ The visionary Internet dreams of the 1990s may have transformed abruptly into a 21st century nightmare. In the early 1990s, I was filled with optimism for the brave new digital world; I followed the burgeoning scholarship on the subject avidly, and became one of the most enthusiastic researchers publishing about its influence on the arts and everyday life. But that fervour has waned and I’m tiring of people’s obsessive fumblings with their phone toys — many have become ‘hopeless junkies’ who can’t seem to be able to turn their damned dream machines off.

I fondly recall a dim and distant past (the 20th century) and an idyllic, golden age when people would sit contentedly and simply watch the world go by – and they still do in certain cultures. It was one of the best things you could ever do, since it seemed that you could ‘take the whole world in’ through the microcosm. You were open and available for ‘live interaction’ with whosever passed by, or you could simply stare into space and ‘daydream.’

Today by contrast, whenever there’s an idle moment, there seems instead a dark compulsion to stare at a phone (or any screen will do). It has become a type of Pavlovian conditioning whereby anyone finding himself, for example, sitting alone in public, or simply being somewhere ‘waiting,’ must whip out their phone in a trice and gaze moronically at it. Sometimes, of course, it’s to view or communicate something important. But more often – and I suspect first-and-foremost – it’s as a default ‘defence mechanism’ to instantaneously shield us from the quotidian world. Phones may have become dream machines, but they are robbing us of daydreams. Most often, phone dreams are dull distractions from direct thought or action, they’re rarely visionary, and are generally banal. That the whole of human life and experience has started to migrate inexorably into a metallic lump of circuits is deeply saddening.

The phenomenon seems particularly strong here in Southeast Asia, where the old opium pipe dreams have transformed into a new form of mirage … and dependency. We live in an increasingly somnambulant society, where the opiate hallucinations of the region’s past have turned into a craved addiction for the ghostly, ephemeral apparitions of social media.

I snapped a photo the other day, which I’ve entitled: The Answer is Action: but not often when you’re lost in your dream machine … (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The Answer is Action, 2016

Dreams, Clichés and Visionary Theatre

There are many potent clichés about dreams, and the best one of all is that ‘they can come true.’ Occasionally they do. The ideology of the ‘American Dream’ is that if you are determined enough, hardworking enough – and perhaps also, selfish and ruthless enough – you can succeed ‘beyond your wildest dreams.’ And when you’ve made it, when you’re at the top, you can ‘live the dream.’ Marilyn Monroe once said that there must be thousands of girls like her sitting in their rooms, dreaming of being a movie star, but she was dreaming the hardest.

Theatre and opera director Robert Wilson has also dreamt hard to become one of the great auteurs of dreamscapes. His stage works are exercises in dazzling design, incandescent light and devastating images; he is one of the art world’s most original and mercurial fictive dreamers.

Theatre comprises many things, but perhaps most fundamentally bodies, space, light and time. Wilson does mesmerising things with each and every one of these. The performers’ movements are stylised and heightened in such a way that apparent minimalism becomes maximalism; and his command of space and light, (his first degree was architecture), is breathtaking. When these elements are combined with an unnerving manipulation of theatrical time, the effect is ‘real yet unreal, and utterly dreamlike,’ as in his productions of Peter Pan (2013) and Pushkin’s Fairy Tales (2015) (Figures 10 and 11).

In some of his productions, figures cross the stage with the millimetre-by-millimetre momentum of a glacier. His mischievous playing with time, slowing it, elongating and seemingly extruding it is exquisite, but also so excruciating that it hurts. No one in the history of theatre has brought the notion of time, tempo and temporality so much to the fore; and this is doubled through his trademark use of repetition.

Physical gestures, musical phrases, and pieces of text are repeated over and over again. In I WAS SITTING ON MY PATIO THIS GUY APPEARED I THOUGHT I WAS HALLUCINATING (1977), the second act is an exact repetition of the first, but the monologue is performed by a female actor (Lucinda Childs) whereas the first was performed by a man (Wilson himself). At one level it is ridiculous, illogical. But on another it is inspired, and its braveness and vision produces a mesmeric effect, a truly uncanny dream. As the philosopher Gilles Deleuze has written: “There is a paradox that something truly NEW can only emerge through repetition.”

Dreams are endless repetitions of our own, and the collective, subconscious. Like art, they embody and enact personal and universal hopes and fears, and conjure visions of angels and demons, darkness and light. All dreams are fictive dreams, and all dreams are real. We freeze time and traverse space. We dream alone, yet we all dream together. As we do so, taking Robert Wilson as our lead, let’s try to dream more beautifully and lucidly.

As Jorge Luis Borges asked: “Who will you be tonight in your dreamfall into the dark?”

Figure 9. Robert Wilson’s Peter Pan, 2013. Photograph © Lucie Jansch

Figure 10. Robert Wilson’s Pushkin’s Fairy Tales, 2015. Photograph © Lucie