8th March, 2016

Đà Nẵng, zero five hundred Golf, Astronomical Twilight

A party of some 20 men lie flat and face-down on the white sands of China Beach. On the command “sẵn sàng, căng!”, they push themselves up to their elbows, slowly lift their heads and shoulders and look up at the sky.1 They hold for 15 seconds and repeat two times. Roughly 50 feet further up the shore, a zombie-eyed re-embodiment of a U.S. Army nurse from ABC television-series China Beach lies fully uniformed and lipsticked in classic beach-pose on her side. She leans her head on her left hand and speaks to the camera: “Make no mistake about it. Vietnam is a hotbed… (she pauses to look at a chopper that does not pass overhead) …of opportunity.”2

The sound in the background is that of low-flying “Huey helicopters scoping out the beach for Air Force and Army nurses who might be sunbathing, hopefully topless,” as one former pilot recalls in his memoir from the time when Đà Nẵng not only hosted the world’s busiest airport but also the U.S. Army’s main in-country station for Rest & Relaxation (R&R).3 Back across the boulevard, on a high-rise with a grand view on Cầu Rồng, the prize-winning and pyrotechnically equipped Dragon Bridge that roars and spits plumes of fire on the weekend, lies the nurse. She reclines on a hammock by the rooftop swimming pool taking in as much joy as the living dead can have in her second life as a real-estate agent. In the background, the early morning sounds of metal hitting concrete from the construction site can be heard. There’s more and then some throughout the city, where scads of tourist hotels and holiday resorts, most of them gated vacation communities, are popping out of the ground like wild mushrooms.4 “Đà Nẵng”, she says, “I am an idea whose time has come.” And if it ain’t the truth, it sure is real. The red gold-starred Communist Party flags that lined the streets since 1975 were removed from the urban landscape last year and in their stead, the impending shift towards a consumerist society is being brand-marketed through Vietnam’s newly found American love-affair, complete with Hotel Elvis, and Obama Bar.

And their affections are also being kindled in the smoke-filled room. After Obama visited Vietnam this summer for talks on China’s expansion in the South China Sea, and announced the lift of the U.S. embargo on lethal arms sales which had been operative since the ’60s, the return of American military units to its shores is becoming a very real prospect for the not-so-distant future.5 It was because of recent events that the name China Beach was snuffed out in 2010 with a ban on hotel’s use of the word ‘China’ for promotion in any way, shape, or form.6 And not because of any resentment towards the American troops that named it. They are quite welcome and especially on behalf of young Vietnamese under 30, who comprise no less than half of the entire country’s population and whose recollection of the war has little meaning to their daily lives or future ambitions. This tech-savvy generation is rapidly shaping their lifestyle by adopting global trends which they can access online. And which is spilling out as an unmistakable desire to look like America.7

Back on the shore, distant trumpets begin to sound with the glorious song of why and how it all began. “He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat; He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment-seat; As He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free”… and so on. In the foreground, the apparition of a ghost by the name of Big Jim stands silently squinting at the sun. He does not know what he is doing there, or who he is or ever was. He remembers he once embodied Jim Morrison, revived as a guardian angel in the 21st century, but also has a particularly strong recollection of that day in 1964 when he visited his father on the USS Bon Homme Richard. This was only some months before Admiral Morrison commanded the U.S. naval forces into the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, sparking the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. They had declared each other dead that year. Standing with his back to the sea, he still wears his timeworn, bare-breasted, sleeveless hemp-jacket, but now also an army cap, combat trousers and two dog-tags dangling beside the black stone necklace he wore at the Hollywood Bowl in the zoned-out summer of ’68.

That summer was shortly after the Tet Offensive had made quite suddenly clear that the U.S. presence in Vietnam might actually not be a won battle. The countrywide strikes throughout January-February of 1968 had struck terror into the hearts of imperialism, and shock froze many Americans’ uncontested belief that the U.S. was an undefeatable force whose troops in Vietnam were practically superheroes.8 And for the first time, the realities of war were being blasted into the world’s living rooms – uncut and uncensored – through the beams of the television screens. Still squinting, Big Jim lifts up a voice… “Flying high, flying high, Am I going to die?”

Meanwhile, in a hotel room, Hanoi Hannah’s voice sounds over the radio: “How are you, GI Joe? It seems to me that most of you are poorly informed about the going of the war, to say nothing about a correct explanation of your presence over here. Nothing is more confused than to be ordered into a war to die or to be maimed for life without the faintest idea of what’s going on.”9 Big Jim lies spread-limbed on the bed and changes the stations but hears only static. Head-shot upside-down, he gazes at the fan on the ceiling. The sound of a passing helicopter fades into cymbals and a guitar-riff, and then the lyrics: “This is the end, beautiful friend. This is the end, my only friend, the end. Of our elaborate plans, the end. Of everything that stands, the end…”10 When he opens his eyes, the fan is still turning, now in the daylight-sensor activated purple backlight bleeding from the cornice of his suite. He turns his head and looks into the camera, eye-to-eye. “Did you have a good world when you died,” he asks, “enough to base a movie on?”

Whatever the claims about victors writing history, the war of attrition and guerrilla warfare certainly made for plenty of American movies over the past decades, which encountered little trouble in telling narratives from the U.S. perspective. In Specters of War – Hollywood’s Engagement with Military Conflict (2012), Elisabeth Bronfen claims that “cinema functions as a privileged site of recollection, where American culture continually renegotiates the traumatic traces of its historical past, reconceiving current social and political concerns in the light of previous military conflicts. As a shared conceptual space, cinema sustains a reflection of and on the past.”11 This entertainment-as-dream-as-PTSD-relief and “national iconography of redemptive violence” is not only directed at the traumas from the actual carnage of war, but also at those from cinematic re-conceptualisations of them.12 Hollywood war films “continue to attest to the way soldiers never fully return home, even when they bring nothing more than quiet despair back with them from the war zone. In a similar vein, we, revisiting their experience on screen, also never fully work through the experience that the stars of these films embody for us.”13

Stranger and more dangerous things than the enemy, lurk in the thick of the forest. In the humidity and mosquito-clad, dingy labyrinth of the A Sầu Valley or “Valley of Death,” the spectre of Tele-Dorothy walks, to the haunting realisation that she seems to be dreadfully lost. Searching amid the foliage for a path, an exit, a way leading home, a phrase crosses her mind, “It has been written I should be loyal to the nightmare of my choice.”14 She walks on. In her mind, she tries to remember the guiding words that the good witch spoke to her: “Follow the Ho Chi Minh Trail… Follow the Ho Chi Minh Trail…” And there, at the edge of the “colossal jungle, so dark-green as to be almost black, fringed with white surf… far, far away along a blue sea whose glitter was blurred by a creeping mist,” it lies: the Yellow Brick Road.15 She once heard that from above, it “appeared as a massive yellow streak meandering its way north and south with tributary roads breaking off in all directions.”16 Some call it hell, some call it home. She follows it, until it finally opens up to the beach and to a wide, open view of the brightest full moon she ever saw.

Not to touch the earth

Not to see the sun

House upon the hill

Moon is lying still

…The mansion is warm, at the top of the hill

Rich are the rooms and the comforts there

Red are the arms of luxuriant chairs

Wake up, girl, we’re almost home

We should see the gates by mornin’

We should be inside the evenin’

Soon, soon, soon

Moon, moon, moon

I will get you17

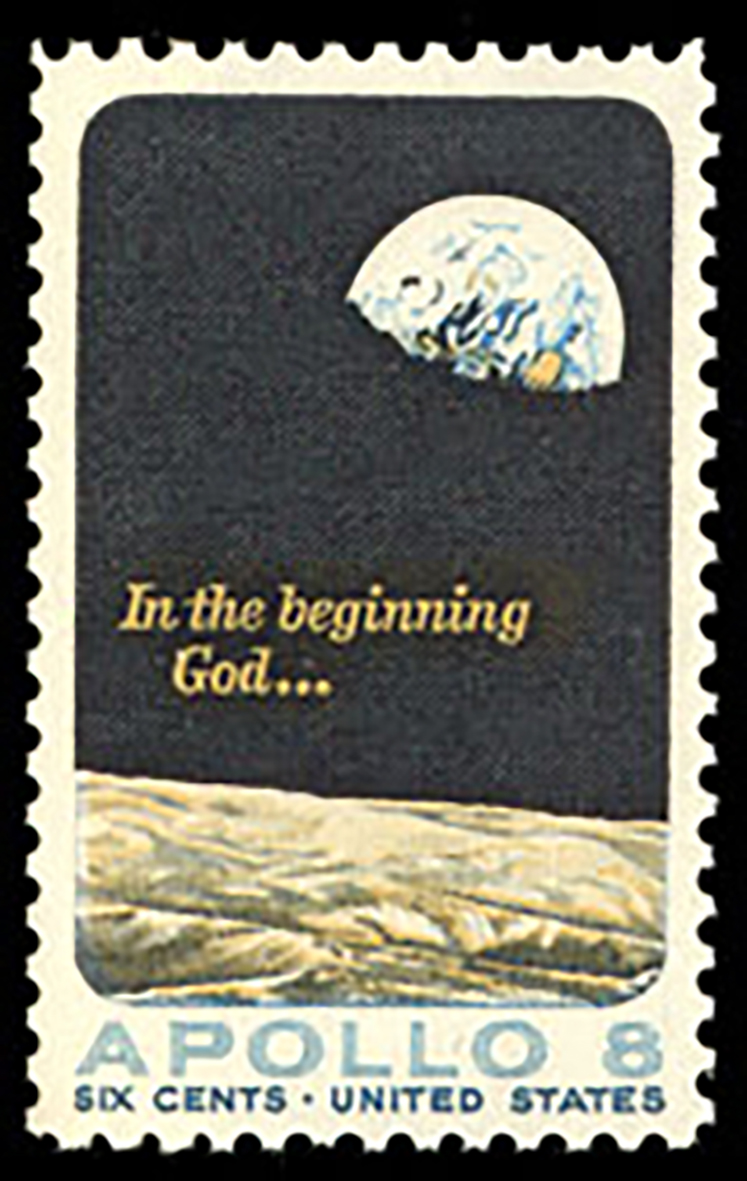

Day breaks at the foot of the Marble Mountains, where a block of stone from the quarry is being transformed into a life-sized Apollo astronaut, neighbouring a Happy Buddha, a Pietà, and a multitude of unicorns, dragons, monkeys and pixiu. “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep… And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas – and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.” One Private Jim who “had just heard over AFVN radio, that the moon landing had taken place” recalls going outside to look at the moon: “All I could think of was how far away they were compared to my situation… It seemed strange – the great amount of human endeavour in technology to put men on the moon and there I was in the middle of a war. Seemed like two opposite ends of human achievement.”18 Rotating from dusk to dawn, ebb and flow, the figure is now being forged out of the slabs of the earth, assuming the posture of Buzz Aldrin walking on the surface of the moon.19

In truth, the U.S. was exceptionally well aware of the value of bridging distance. Having taken heed of the power of television in simulating proximity to deeply influence emotional response on a mass scale, they were now intent on taking advantage of this magical medium towards a victory of their own. NASA was in pains not only to land man on the moon, but also to televise the event live across the world.20 Some conspiracy theorists even claimed the Apollo programme was a fake to distract the world from the war in Vietnam. Others, who took the moon landing as a fact, saw at least a strong connection: “The American Patriot Friends Network claimed in 2009 that the landings helped the United States government distract public attention from the unpopular Vietnam War, and so manned landings suddenly ended about the same time that the United States ended its involvement in the war” in 1972.21 Whatever the case may be, and even in the event that the NASA’s film footage had been directed by none other than Stanley Kubrick himself, in the earthbound London-suburb set he had created for 2001: A Space Odyssey (as his wife had claimed), it was the most widely watched broadcast in the history of television, and even won an Emmy 40 years later.22 On Christmas Eve, 1968, the world’s televisions flickered in concert, and where the dark images of war once shown, pristine whites and greys lit up the screens. Some would have thought, “It’s not easy facing up when your whole world is black.”23 But that day, the U.S. felt second to nobody: “…Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.” And the public compliantly followed suit, in “an escapism that made use of the universe as an ivory tower.”24

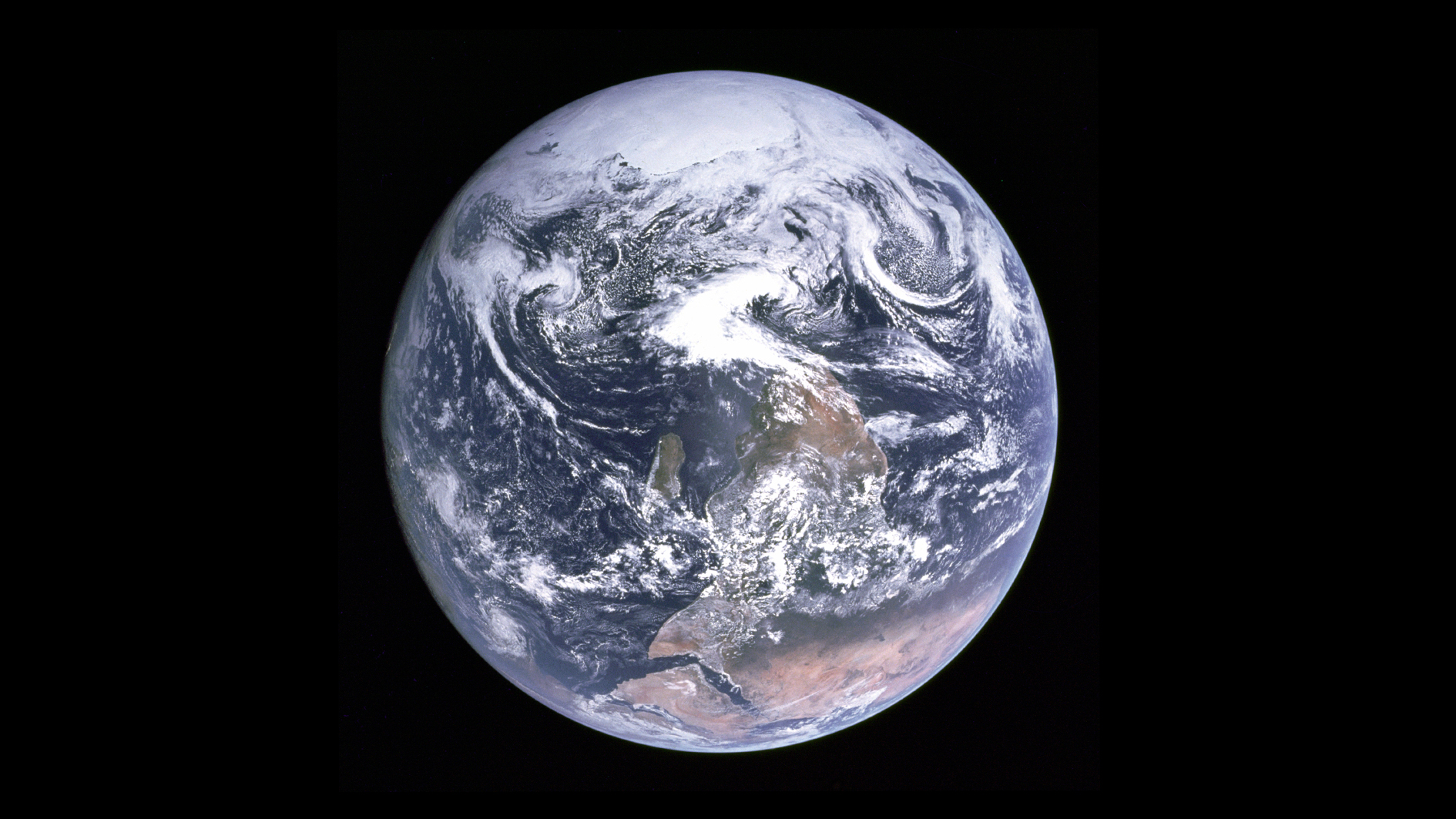

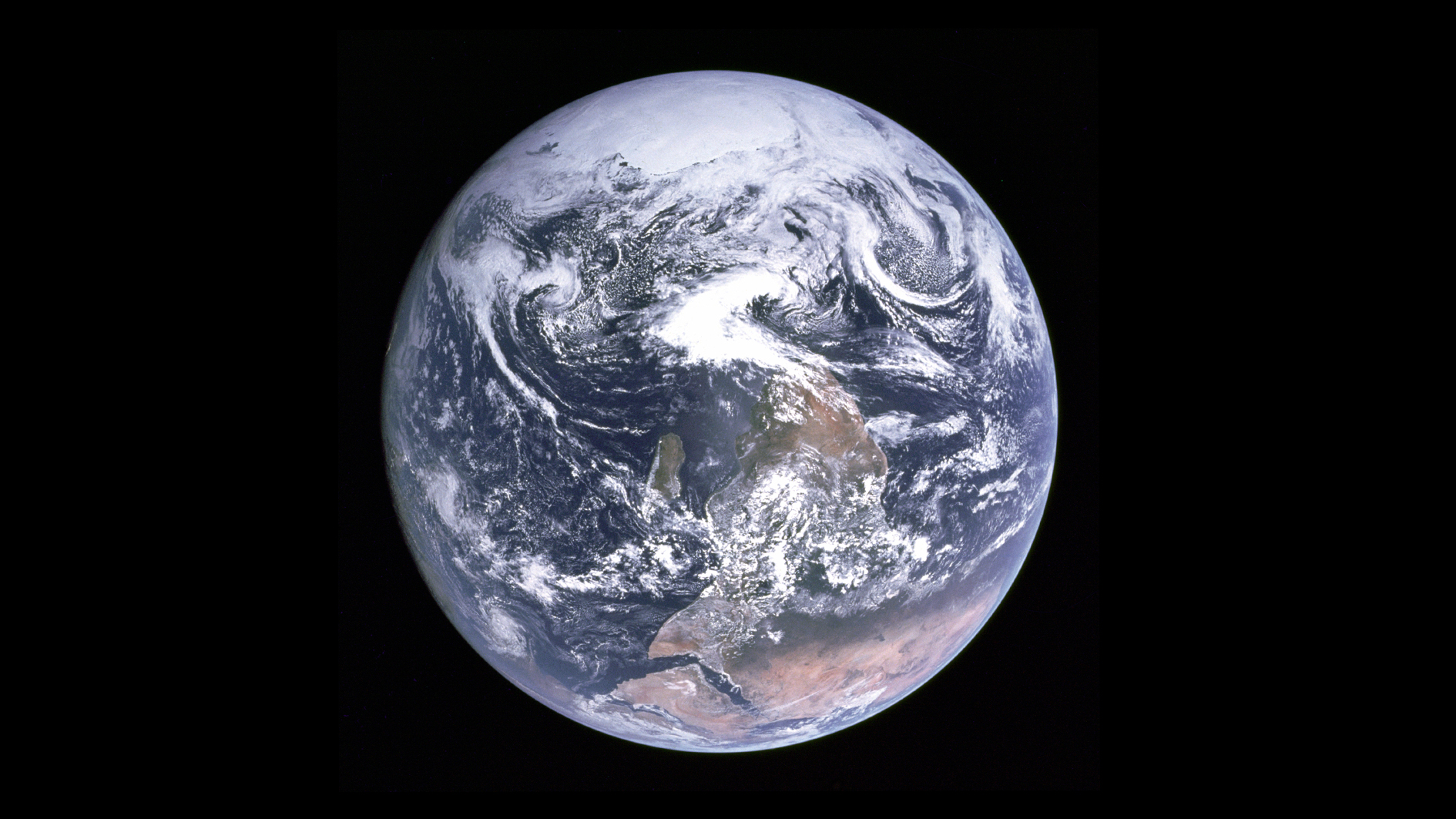

But by releasing the image of the whole earth, the struggle for ideologies and national borders also came into question. For the first time in history, humankind looked at the fragile blue marble. It was the beginning of a global ecological movement, and a booster for economic globalisation. The Whole Earth Catalog, first published by Stewart Brand in 1968 “played an essential role in mediating between technological determinism on the one side and hippie revolt, i.e. back-to-nature romanticism, on the other.”25 Released in the same year as The Mother of All Demos, in which Brand was also closely involved, the two worked in tandem towards an interconnected and collaborative, if not collectivist vision of the human race.26 Based on the key principles of self-sufficiency and sustainability, the aim was to provide users with technological and knowledge-based tools that would empower them to “know better what is worth getting and where and how to do the getting.”27 The ensuing shift would supplant the old order of “remotely done power and glory—as via government, big business, formal education, church,” with a new model that was determined by proximity: “intimate, personal power.”28

Up in the heights, Frank, Jim and Will were the first to see Earth in its entirety. Nobody anticipated it would be of any interest to look back:

For its first three revolutions, the astronauts kept [the Service Propulsion System (SPS) rocket’s] windows pointing down towards the Moon and frantically filmed the craters and mountains below… It was not until Apollo 8 was on its fourth orbit that Borman decided to roll the craft away from the Moon and to point its windows towards the horizon in order to get a navigational fix… A few minutes later, he spotted a blue-and-white fuzzy blob edging over the horizon. Transcripts of the Apollo 8 mission reveal the astronaut in a rare moment of losing his cool as he realised what he was watching: Earth, then a quarter of million miles away, rising from behind the Moon. “Oh my God! Look at the picture over there. Here’s the Earth coming up,” Borman shouts. This is followed by a flurry of startled responses from Anders and Lovell and a battle – won by Anders – to find a camera to photograph the unfolding scene. His first image is in black-and-white and shows Earth only just peeping over the horizon. A few minutes later, having stuffed a roll of 70mm colour film into his Hasselblad, he takes the photograph of Earthrise that became an icon of 20th-century technological endeavour and ecological awareness. In this way, humans first recorded their home planet from another world. “It was,” Borman later recalled, “the most beautiful, heart-catching sight of my life.”29

Later this came to be called ‘The Overview Effect,’ a phrase coined by philosopher and writer Frank White, in his book of the same name, which “refers to the experience of seeing firsthand the reality of the Earth in space, which is immediately understood to be a tiny, fragile ball of life, hanging in the void, shielded and nourished by a paper-thin atmosphere. From space, the astronauts tell us, national boundaries vanish, the conflicts that divide us become less important and the need to create a planetary society with the united will to protect this ‘pale blue dot’ becomes both obvious and imperative.”30

In the case of Buzz, this insight-bordering-on-sacrosanctity took a foul turn with a catholic tang. He recounts what he did while the cameras stopped running: “I poured the wine into the chalice our church had given me. In the one-sixth gravity of the moon the wine curled slowly and gracefully up the side of the cup. It was interesting to think that the very first liquid ever poured on the moon, and the first food eaten there, were communion elements.”31 This is especially striking given that the 1966 Geneva “Treaty for Outer Space” stated that “astronauts are envoys of mankind” and that “Space activities and their results are to be reported for the benefit of all.”32 But Buzz’s idea that his moon communion was in no way incompatible with the “all” and “mankind” parts of Space Law is far from exceptional. Rather the norm, the dictionary entry for “catholic” lists it as an adjective that is synonymous to the terms: “global,” “comprehensive,” “worldwide,” “planetary,” and “universal.”33

In the case of space exploration, something similarly unsettling and territorial transpired. Objectivist philosopher Harry Binswanger has proposed passing a new policy by which the first person to land on Mars, to reside there for a previously determined amount of time, and return alive, should be given ownership of the entire Red Planet.34 Ron Pisaturo takes it a step further, proposing that: “In order to have a successful venture, a venture to invest in, the property must be valuable… Whoever implements the concept of getting to Mars and living there turns a virtually worthless ball of rock into something of substantial value, into real estate.”35 Even the Whole Earth Catalog, once “a counter-culture archive” that embodied the DIY environmental movement and rising computer culture as a means of empowering society from down up, would later give rise to “digital network capitalism” and “in turn decisively shape the postmodern globalisation euphoria of the New Economy.”36

The Overview Effect has become a marketing tool for the first tourist journeys into the stratosphere, which are corporately owned and which cater to an American public, in Christianly affected aesthetics. A giant silver-coloured balloon hovers in space and a man in a spacesuit dangles from it by a cable, the curvature of the Earth glowing Hallelujah-blue in the background. One can almost hear the angels singing. Today, for only quarter of a million US dollars, one could buy a luxury villa in Đà Nẵng, or a place up in heaven next to Richard Branson and his million-dollar smile: Virgin Galactic Enterprises – Because Space Exploration Makes Life Better on Earth. Either way, the heights and the depths are being made of the same stuff, and are moving steadily towards becoming perfectly indistinguishable.

Except for the US postage stamp (May 1969), Earthrise (1968), and The Blue Marble (1972), images courtesy of Bjørn Melhus.