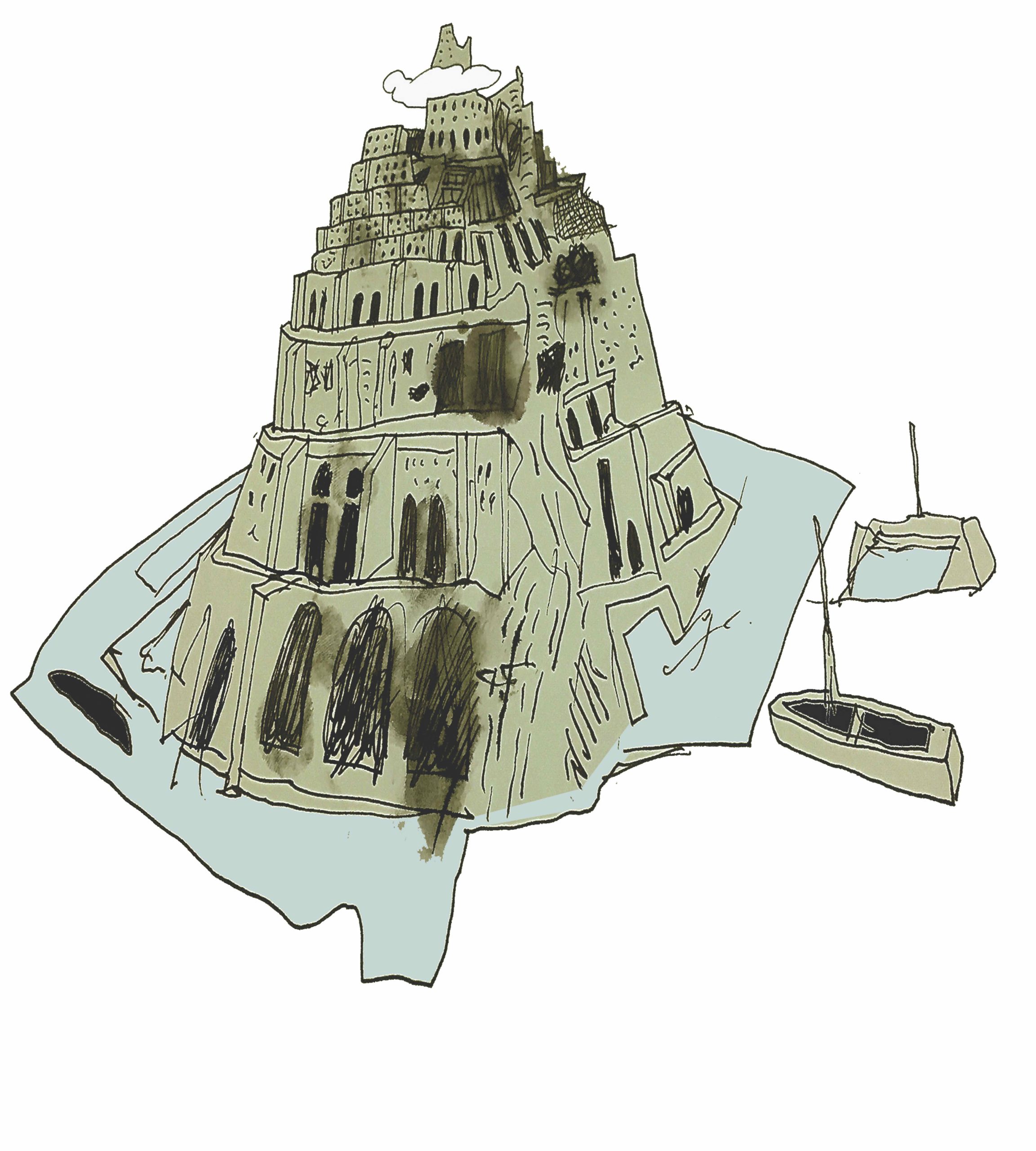

This is an allegory. An allegory that seeks to survey and meditate on a life of observation, reading and perspecting on all things islandic. An oft forgotten idea that manifests in driving the world around the large water bodies and forming communities that are often remembered only to be forgotten. Island: sometimes charmingly pronounced Iss- land or ice-land in many non-English-speaking countries reasonably deceived by the aberrant ‘s’. The ‘s’ remains a peculiarity that Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw and the spelling reform movement (which included Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Johnson, Noah Webster and many more) would have eradicated by the end of the 19th century. They point out that on Shakespeare’s tomb, ‘friend’ is more logically spelled (or spelt) ‘frend’; and amongst hundred of spelling oddities, they targeted the ‘b’ in ‘debt’ and the ‘s’ in island, arguing for ‘iland’ as better phonemic representation. Though complex, the spelling war never drew blood and a persuasive counter logic pleaded to keep the origins of words intact in their spelling – much to the continued despair of school children and foreigners. Keeping a word’s origins visible in its spelling is a sweet argument, until one realises that just as a language continues to evolve, so does spelling – or at least it did, until set in concrete through dictionary definitions.

Traced to a Nordic word of the 700’s, yland became the Old English igland or ealand. The ig, ieg or ea came from the Proto-Germanic for aqua, therefore meaning ‘thing on the water’. Old English also records it as ealand, meaning ‘river-land, watered place, meadow by a river’. In place names, Old English ieg often refers to “slightly raised dry ground offering settlement sites in areas surrounded by marsh or subject to flooding”. Middle English recorded it variously as iland and eiland, as in the Dutch and German forms of the word. The Oxford Shorter on Historic Principles is but one of several modern dictionaries that attempt to record the evolution of a word’s spelling.

Just as the Chinese language has two very different words for isle and island, it is interesting to know that before the 15th century so did the English. In Mandarin, isle is 沚 (zhǐ) and island is 岛 (dǎo), or islands, 岛屿 (dǎo yǔ). According to the Chinese dictionaries commonly used by colleagues in Singapore, ‘isle’ means a piece of small land surrounded by water, whereas ‘island’ is a piece of land surrounded by sea. The Chinese hanzi for water, (水, shuǐ) implies drinkable and that seems also to be the original meaning of ‘isle’, which relates to river and aqua. Shaw might well have argued that the rationalisation of spelling only dates back to the 15th century, but did he know that the language moderators often made mistakes? In the case of ‘island’ etymologists now argue it is from a completely unrelated Old French loan-word, ‘isle,’ which itself comes from the Latin word insula, with its relation to salo, or salt. So the Chinese language keeps the more accurate definition and distinctly different spellings; while the English language has mistakenly taken the ‘s’ into both words. Today, we should take the Chinese lead and only use ‘island’ where the land is in a sea or ocean, and ‘isle’ when in a river or lake. Sumatra is the sixth largest island in the world and only about 12 nautical miles from Singapore, across the world’s second busiest waterway; on this island is the huge Lake Toba, the crater of once an enormous volcano; in this lake is an isle which the Indonesians call Pulau Samosir (the Bahasa word for island, Pulau, does not hint at what kind of water surrounds it); amazingly, in the centre of this isle is yet another small lake. Isles within lakes within islands are surely special places.

In spite of its spelling, or perhaps because of it, the word ‘isle’ retains its magic to this day. We remain haunted by early exposure to it in poetry and stories. Like Caliban’s salty synonym, it conjures paradise and music:

The isle is full of noises,

Sounds, and sweet airs,

that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears,

and sometime voices.

(Tempest, Act 3, Scene 2)

As in Yeats’ Lake Isle of Innesfree (1888), the word ‘isle’ remains idyllic and calling, even when location is lost.

I will arise and go now,

and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there,

of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there,

a hive for the honey bee.

Music and magic also surrounds King Arthur’s resting place in the legendary Isle of Avalon – now pretty much proved to be the grounds around the Tor of Glastonbury – in numerous books, including Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (published between 1859-1885):

And slowly answer’d Arthur from the barge:

“The old order changeth, yielding place to new,

And God fulfils himself in many ways,

Lest one good custom should corrupt the world …

But now farewell. I am going a long way …

To the island-valley of Avilion;

Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow,

Nor ever wind blows loudly; but it lies

Deep-meadow’d, happy, fair with orchard lawns

And bowery hollows crown’d with summer sea,

Where I will heal me of my grievous wound.

On such an isle, in a Scottish lake, J.M. Barrie made his heroine Mary Rose (1920) disappear for decades into Fairyland; but Barrie had already called every child with Peter Pan’s magic island of Indians, crocodiles, pirates and lost boys (1904).

We learn early on that ‘Isle’ is but a poetic form of the equally exciting word: Island. And perhaps one’s first association with it springs from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), and Daniel Defoe’s unnamed island where Robinson Crusoe (1719) befriended ‘Man Friday’, the first influential fiction about east-west friendship across a cultural divide. Stevenson’s bones remain buried in Samoa, in the same South Pacific seas as Tahiti, the island that kept Gauguin away from his friendship with Van Gogh, perhaps robbing the world of decades of more masterpieces. Captain Cook must also have left remains, after he was chopped into pieces by the Hawaiians but, according to historians, not before his sailors had infected their paradise with venereal disease and smallpox.

Homer and Tennyson both mythologised the Western Isles, though the ancient Celts also referred to them. Historian John R. Gillis deeply explored the influences of islands upon the western imagination in his 2004 book, Islands of the Mind: How the Human Imagination Created the Atlantic World, looking at the role of islands in economic, political and social contexts in what he calls the Atlantic world (East America and West Europe). Equally important is his 2012 book, The Human Shore: Seacoasts in History, in which he studies coast dwellers and migrations caused by constant and unpredictable fluctuations at the seashore. Gillis has now retired to the Great Gott Island, in Acadia (another word for paradise) National Park, a group of islands off the coast of Maine thrusting into the Atlantic between Boston and Canada. Yet Gillis firmly reminds us that the sea was always considered a “place of chaos and terror, a wilderness filled with implacable beasts – Kraken, Leviathan, Scylla, Charybdis.”

Rodney Hall was moved to fiction by his title, The Island in the Mind (2000), recording the vision of and search for the great south land, Terra Australis, which eluded Portuguese Pedro Fernandes de Queirós (1565-1614), traversing through the Pacific with the Spanish, and so many others who searched for her over centuries. Clearly ‘island’ or ‘isle’ is both real and imaginary. The word implies insularity; and that has virtues as well as dilemmas. Where some islanders have built up richly distinct cultures and unique customs and dialects, others have, for example, starved and inbred though lack of connections to a wider world.

It was probably the concept of purity, untouched and virgin, that drew both minds and bodies to the imagined islands. We all want to believe that paradise remains somewhere, and that in this life or the next it is attainable. The island is everything: evoking legend, magic, adventure, remoteness, and paradise, far from the madding crowd; but the island is also a prison and isolation, both real and metaphorical.

Infamously, as with Alcatraz and Sakhalin, a prison island is sometimes made famous by its prisoner, just as Napoleon put both Elba and St. Helena on the map. An isolated rock surrounded by water might be a safe haven for nesting birds, but for prisoners it was a particular form of hell. France had its dreaded Devil’s Island that imprisoned Alfred Dreyfus, from 1895 to 1899, and which features in Hugo’s Les Miserables (1862) and his Toilers of the Sea (1866). Tourists in Tasmania now visit Marcus Clarke’s hell, all curious to imagine the punishment of Rufus Dawes described so vividly in For the Term of his Natural Life (1874). Another island of infamy was Goat Island in Sydney Harbour where the screams of its chained captives could be heard on shore. On both Australia’s Macquarie Island and on Singapore’s Pulau Senang, experiments in prison reform led to horrific tragedies. Physical suffering never resulted in creativity, though the mind no doubt experiences previously unimagined impulses; but greatness has often been conceived in prisons isolated from the world, for example, Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605-15) and Marco Polo’s journals and later Solzhenitsyn and others, such as Marquis de Sade and Oscar Wilde. When directing Václav Havel’s Vaněk plays, and told of a new one, I once awaited weekly pages of his Protest (1978), each page smuggled out of his Prague prison, and to Sydney via Canada. One thing is plentiful when isolated from the work, and that is thinking time. Hitler, of course, is well known for writing Mein Kampf (1925) whilst in confinement.

James Michener spent a lot of time island-hopping before, during and after the second great war, his best-seller, Tales of the South Pacific (1947) became a most famous musical and its hit song boosted tourism, as more jaded Westerners heard the call of their ‘special island’, and Bali Hai became for a while synonymous with Shangri-la – James Hilton’s mythical inland island, supposedly in the Himalayas, and possibly near Mount Meru, the sacred Hindu mountain linked with the concept of island though the Sanskrit-derived word dvīpa.

Strangely, even in its south, the Atlantic lacks the lush tropical islands that lured Westerners both west and east in search of the Indies and their wealth of magical spices. So it is fair to say the lure of the island contains images of the tropics and all their associated fruits. And garden paradises, though rare in the bible, fill the Koran and Islamic architecture. Water, trees and fruit evoke not only household orchards (in Russian the word for garden and orchard is the same) along the Silk Road, from Xanadu to Samarkand, but also the miracle island within deserts, the oasis.

Various biblical scholars like Dr. John D. Morris, and others at the rather romantic Institute for Creation Research, have identified the geographical location of the biblical paradise (originally from a Persian word meaning ‘park’; translators preferred the Greek word, meaning ‘garden’, thus ‘Garden of Eden’) as being at one of two places (Aden in Yemen being neither). The first, according to Genesis 2:10-14, is at some common point of origin of the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile (which is Gihon in the Hebrew Bible), and Indus or Gangen (which is Pishon in the Hebrew Bible). The second place is apparently in Dilmun of Sumer, near the head of the Persian Gulf. Being near the source of a great river reminds us of the Hindu’s Mount Meru, the centre of the universe surrounded by the waters of life in seven concentric seas. The Hindi word for island is dvīpa, one of 18 encircling Mount Meru, like the petals of a lotus. The holiest island near the source of the waters of life is Jambudvīpa or the island of Jambu, overlooked by the giant jambu tree growing on the summit of Mount Meru.

Paradise, perhaps unsurprisingly, is the name of several towns in the United States, e.g. in California, Nevada and Kentucky; also in Newfoundland and Labrador. As a child, I myself explored the ghost town of Paradise in Queensland, a once prosperous gold mining town in the Burnett Valley, a century before Surfers Paradise was named. My favourite naming of Paradise Island is in the Bahamas, where it was formerly known as Hog Island, possibly linking it to Circe’s island where Ulysses and his men were almost all drugged into becoming swine, an arguably apt punishment for their sacking of Troy.

Today, the islands in what the Chinese now insist is titled the China Sea (an 18th century Western naming), however small and barren, are now potential hotspots for future clashes with Korea, Japan, Philippines and Vietnam. Islands, such as these and the Falklands, famously fought over by late British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, thus represent a nation’s outpost or frontier, and every colony seems to have several. Owning of the seaways around the islands would be a frightening if logical extension of territorial claims. An island such as Singapore, garden isle though it may be, is hemmed in by what in other ways could be seen as an invasion of personal space. Should an island therefore have horizons unsullied by other lands to qualify as exemplars? Can paradise exist right next door and be a contact temptation or invitation to invasion? Remarkably, small island-states have always existed in Europe such as renaissance Venice and Florence, and for a while Singapore’s return to nation-state status pointed the way to a different future, especially when ethnic, language or cultural islands had their original borders ignored in the rushed reconstructs created after the major wars.

In terms of an economy best suited to empowering people and their needs, as economist E.F. Schumacher so convinces, small is beautiful; and smallness in nations and islands always ensured distinct customs, speech and art. Even an island as small as Britain, divided itself into over 86 counties, each with identifiable dialects (and in the case of Wales, a different language with 30 variants). It is well known that China, India and Indonesia, to name only the largest, all have many unique languages and, within each, many more dialects. A belief system is always related to a language and perhaps language is the best way to identify a nation – the term nation has replaced what many consider the more derogatory word ‘tribe’ when speaking of North America and Australian indigenous groups. But tell that, if one could, to Lord Louis Mountbatten and his advisors who drew the cruel partition right through regions where people were previously bonded by language, despite their religion. Now we have the western side of Bangladesh subdivided into an artificial island created by language, Bengali.

Artificial islands never seem to have the true grounding that we value in place; but they are growing in number, just as Singapore has grown in size by landfill and purchases of soil from mostly uninhabited Indonesian Islands. Much future-telling expands upon the benefits of floating islands built from the world’s debris, but we are yet to find a safe and satisfactory way of securing our nuclear waste. Floating islands claim their place in the imagination and recently reached wide audiences though Ang Lee’s 2012 film of Life of Pi, suitably enchanting the place and giving it an evil tint that is not always associated with a floating island.

Evil, however, seems very much part of the Great Pacific Garbage patch, or Pacific Trash Vortex. Consisting mainly of man’s blessing and the planet’s curse – plastic – some claim that the debris floating in the slow whirlpools in both the Pacific and Atlantic will one day consolidate. Known first as the World’s Garbage Patch, it was once as big as Texas; but now it links two vortices: the Western Garbage Patch (below Japan and east of Philippines) and the Eastern Garbage Patch (between Hawaii and California) and is said to be twice as big as the United States in area. The Atlantic has similar, but smaller islands of debris, likewise growing in both north and south. But they can never anchor, as strangely they drift over the world’s deepest underwater canyons, which in turn are not far from real islands which are but the peaks of great underwater mountains. Oil-spills from oil-tanker leaks and wrecks, and pumice rafts from volcano ash also form floating islands with no allure.

Nature’s own floating islands should perhaps be called isles, as they are found in marshlands, lakes and still waters, sometimes in cenotes or sinkholes. Usually made up of a mass of aquatic plants, mud and peat, floating islands have their own magic, much as the giant lily pads that could support a toddler. Once part of mainland vegetation: reeds, bulrushes, and or water-hyacinths, water-lettuce and waterferns such as now clog Asian waterways like the Mekong, they broke away and floated free. Grillis cites the Marsh Arabs, who live ‘amphibiously’ on floating islands of reeds, as having learned to adapt to the fickleness of shifting water levels. The largest floating islands are said to be on Lake Titicaca in Peru where the Uros people live, originally using nature’s isles for safety from aggressive neighbours. Tenochtitlan, an Aztec capital, was once surrounded by floating gardens, which primarily supplied fresh vegetables. Modern artificial islands mimic the reed-beds of the Uros peoples and are increasingly used by local governments to reduce pollutants and increase water quality. China is now developing the water-garden concept on a large scale, mastering aquaponics to grow rice, wheat and canna lilies on two-acre islands. Floating islands were boasted as being part of the massive Ming Dynasty flotillas of Cheng Ho (Zheng He); they carried soil in which fresh vegetables could be grown; and scurvy was never part of the great Chinese merchant fleets that kept peace from Madagascar to Makassar, forming Asia’s own Camelot.

Island nations are common and Singapore is one. It is also called an island-country, the garden-island, and sometimes an island-state. In the United States, the island-state is Hawaii, itself consisting of 137 officially islands and another 15 named ones; in Australia, the island-state Tasmania, is primarily one. Guam is not an island-state because it is a territory of the USA, and one of 17 such territories. All definitions of ‘island’ record that it is land “smaller than a continent” – without defining a continent’s size. Australia calls itself an Island Continent.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) is an organisation most active in climate change conferences, putting forward the first draft text of the Kyoto Protocol as early as 1994. It has 39 members, all low-lying coastal or island countries, 37 of which are members of the United Nations (UN); with 19 in the Atlantic, 16 in the Pacific (one of which being Singapore), four in the Indian Ocean, and a growing number of ‘observer’ members, including American Samoa, Guam, Netherlands Antilles, Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands. These combined voices do not include some of the world’s most endangered island cities such as Venice and Bangkok, but they now lead the world as environmental watchdogs, especially becoming the carers for our oceans. Significantly, at the recent Warsaw climate change conference they pushed for the establishment of an international mechanism of aiding victims of the ‘super-typhoons’ (eg ‘Haiyan’) said to grow as a direct result of global warming. In 2009 at the UN, members from the island state of Tuvalu demanded that global temperature rise be set at 1.5 degrees instead of the proposed 2 degrees. Tuvalu, formally known as the Ellice Islands, of some 11,000 Polynesians on only 26 square kilometres of three reef islands and six atolls, is far to the east of Papua, deep towards the Pacific’s centre. Islands will be the first to be lost in the inevitable melting of the ice caps, and already many villages and families have been moved off the lowest. Sadly, this seems never to reach mainstream media, and the rate is said to be faster than anthropologists can record the details of these disappearing islands.

2014 was the International Year of Small Island Developing States, a year celebrating the “extraordinary resilience and rich cultural heritage of the people of small island developing states “ (UN Sec-Gen, Ban Ki-Moon) culminating in a UN Conference in Apia, Samoa. Though the year focused on building partnerships between members, it brought pressing global issues to the forefront, and uniquely sought to find solutions through innovation, science and through traditional knowledge. The ‘island mentality’ seems to have selected the best of what the world has to offer, whilst living closer to nature and more consciously its carer. It has created what is now referred to as ‘The Island Voice’.

The Island of Great Britain is part of a sovereign state, together with Northern Ireland and, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, another 6,000 isles and islands, such as the Isle of Man in the Irish Sea and Queen Victoria’s retreat on the Isle of Wight (both of these ‘isles’ are surrounded by salt water), but in fact Britain is only the 80th largest sovereign state in the world. However, it is the world’s third most populous island after the Java and Honshu. Not counting Australia, as it is considered a continent, Greenland is the largest island in the world at over 2 million square kilometres (though some think that underneath the ice it is actually three islands); New Guinea is second largest at almost 800,000 square kilometres, followed closely by Borneo; then Madagascar and Baffin Island (Canada) around 500,000 square kilometres; the sixth largest island in the world is Sumatra, at 481,000.

Indonesia’s government officially records that it has 17,000 islands, 8,844 named, with 922 permanently inhabited; but Indonesia’s National Institute of Aeronautics and Space, established by Soekarno in 1963, has recently counted 18,307 from satellite. According to the United States Geographical Survey there are a staggering 18,617 named islands in the United States and its territories, outnumbering Indonesia by 310 islands; 2,500 of them are in the state of Alaska, and Florida Keys is actually 60 small islands. In Arkansas, where one might expect a dozen at most, there are 142 named islands, including such as the imaginative, ‘Island 28’ and similar. Comparatively, the Philippines has ten thousand less, at 7,107 (seven of which are missing during high tide) and Japan has 6,852 islands; similar to the Philippines, Japan’s four largest islands comprise the majority of land. Malaysia has 879 islands, Sabah state having the most, with 394; but offshore Malaysia counts another 510 geographical features, that could pass for islands.

Singapore lists over 60 islands, with the well-known Sentosa (Pulau Belakang Mati), Saint John’s Island (Pulau Sakijang Bendera) and Pulau Ubin all popular destinations. Included in the 60 are 10 artificial islands, such as Japanese Garden in Jurong Lake, and Treasure Island in Sentosa Cove. These partly make up for islands which formerly belonged to Singapore: Christmas Island, sold to Australia in 1957 (for 2.9 million Australian pounds); Pulau Saigon, once in the Singapore River but added to its southern bank in the late 20th century; Terumbu Retan Laut, now part of the Pasir Panjang Container Terminal on the main island.

The mystery and intrigue involved in the naming of islands are endless. Niue, despite Cook naming it the ‘Savage Island’, was never cannibal, and its inhabitants were not even betel nut chewers that elsewhere gave the impression of spitting blood: the red on the Niue people’s teeth was from hulahula, a local red banana. Bali is called the island of the Gods, though international tourists, seeking paradise, seem to have long ago driven the gods away. Cuba is called the island of music and, now open to tourists, is a musician’s paradise, not far from the island of Jamaica, of which Harry Bellefonte sang patriotically in Island in the Sun, “willed to him by his father’s hand” and echoed paradise’s elements of “forests, waters and shining sand”.

The Isle of the Dead, one of many paintings by Swiss symbolist, Arnold Bocklin, and a 1945 horror movie by Tim Southern, starring Malcolm McDowell, remains arguably the most haunting of titles. Poveglia is also known as the Isle of the Dead, primarily because of its 18th century mass plague graves, a small and famously haunted island located between Venice and Lido in the Venetian Lagoon. But Isola de san Michele is the official cemetery of Venice, the majority being Catholic but with small sections for Greek Orthodox or Foreigners – Jews being buried in nearby Lido, very new compared to Poveglia. Isola de san Michele contains the graves of Igor Stravinsky and Ezra Pound. Apart from the Venetian cemeteries, an island of the dead could be Skyros, where the WWI poet Rupert Brookes died of an infected mosquito bite, given probably in the very olive grove where he now lies in Greece’s Aegean Sea. Relatively near, the Cretans claim the graves of Zeus, of King Minos of Knossos, and of Nikos Kazantzakis (the author of Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ). The Island of Crete was also visited by St Paul, who, in letters to Timothy, supported the view that the people of Crete never let the facts get in the way of good story.

As Feste sings in Twelfth Night: “Come away death… In sad cypress let me lie,” the cypress tree is commonly found in Mediterranean cemeteries, but Shakespeare could as easily have spelled it Cyprus; especially as Twelfth Night is but one of his many plays set near the Mediterranean, and his only play to refer beyond India (home to the child over which Oberon and Titania quarrel) to the more magical ‘Indies’. Grave stones attest that Portuguese were being buried in Malacca (Melaka) while Shakespeare was writing.

Located by Jules Verne as 2,500 kilometres east of New Zealand, The Mysterious Island, reached by American civil war escapees on an air-balloon, proves to be the last resting place of Captain Nemo and his Nautilus, the world’s first submarine. Another 10,000 miles to the east is South America and its important offshore islands of mysterious Easter and evolution’s Galápagos. The mysteries of island-hopping in miniature islands we call canoes and boats, thousands of years ago, still fascinate anthropologists, botanists and palaeontologists, as DNA samples and cultural traits argue various migration routes across the vast pacific from both east and west.

So where has this criss-crossing of both time and space led me? Assuredly, the island calls us all, and features in maps and writing from earliest times. Islands are as ancient as continents and can be equally said to be made by God’s hand, and therefore selected to serve some divine purpose. Surfing Google maps, courtesy of today’s satellites and aerial photography, gives access to a new island-hopping, and there we can see magic that the real explorers, and tourists, cannot see from the ground: the endless and alluring patterns shaped by nature and echoed by man in his stone walls, fences, dykes and rice terraces. We do tend to be preoccupied with recreating versions of islands, in offices, in kitchens, living rooms, as we build partitions as equivalents of waterways. And ‘island’ has become a handy word for identifying groups, cultural, educational, religious or linguistic: an island can be both hell and heaven, imagined or real; it endlessly fascinates as destination or as metaphor. The fact that an island is isolated, often remote, adds to its lustre and allure.

In art, and in my resistance to naturalism, I have always encouraged symbols, metaphors, allegories and ways to engage the imagination of the reader-audience. Journeying with great writers through their perceptions of ‘island’ continues to enrich me, though I discovered long ago that I can take only so much of island paradise before I want to island-hop to a new destination. I have been interviewed on radio and literally played the music I would take to a desert island and talked of the books; but, as with music when travelling great distances, one never really can guess what one will crave for on either journey or destination. I think I prefer the metaphor to the reality; like the picnics in the Forest of Arden, alas there were ants and mosquitoes. Hence my quest for the island was also a search for a theme. And I believe I found it with the ducats in one of the pirate chests left behind by Long John Silver: islands, real, fictional and in concepts, are and have always been, a vivid stimulus to the imagination. And what after all is more important than imagination? It seems that island is a place where the imagination wants to play. But, more than that, is not island a call to venture forth, to adventure?

Following close on the end of the war in the Pacific, Rogers and Hammerstein, at their best, dared to write of east-west love and the call of the ‘other’ in South Pacific (1949). They gave these words to Bloody Mary and her broken English:

Most people live on a lonely island,

Lost in the middle of a foggy sea.

Most people long for another island,

One where they know they will like to be.

Bali Ha’i may call you,

Any night, any day,

In your heart, you’ll hear it call you:

“Come away…Come away.”

If there were no island imagined just beyond the horizon, would mankind ever have been called to leave the cave, to adventure there, and beyond? And is, perhaps, the next island the one we really want? Is the island ever greener just beyond our ken?