Royal Society et al. ‘The eruption of Krakatoa, and subsequent phenomena’.

Report of the Krakatoa Committee of the Royal Society.

London, Trübner & Co., 1888. Plate 1: Lithograph of 1883 eruption of Krakatoa.

The first island I remember hearing about as a child was of Krakatoa obliterated in 1883. Too young to fully comprehend the horrific loss of life, I was fascinated instead by the factoids that accompanied it. That the explosions were heard halfway around the world. That weather patterns were disrupted by clouds of dust, ash that orbited the globe, and that the shock waves circled the planet seven times. That spectacular sunsets were visible all around the Earth for a year, and in the British Isles, those sunsets would be captured by landscape painters. That the force of the final explosion (always measured in comparison to nuclear blasts) made an island disappear. And so my first island was not an island at all.

The second was Bikini Atoll. To my unformed child-brain, this was a human experiment made to imitate nature, like the helicopter and the dragonfly. I imagined radioactive clouds in colours of similar spectacular sunset, and wondered if particles still lazily circumnavigated the globe. I knew some had made landfall in India. But I was disappointed that no island had disappeared. At the very least there should have been a Santorini-like caldera. Unsurprisingly there was very little information about nuclear tests available to an inquisitive child living in India during the Cold War.

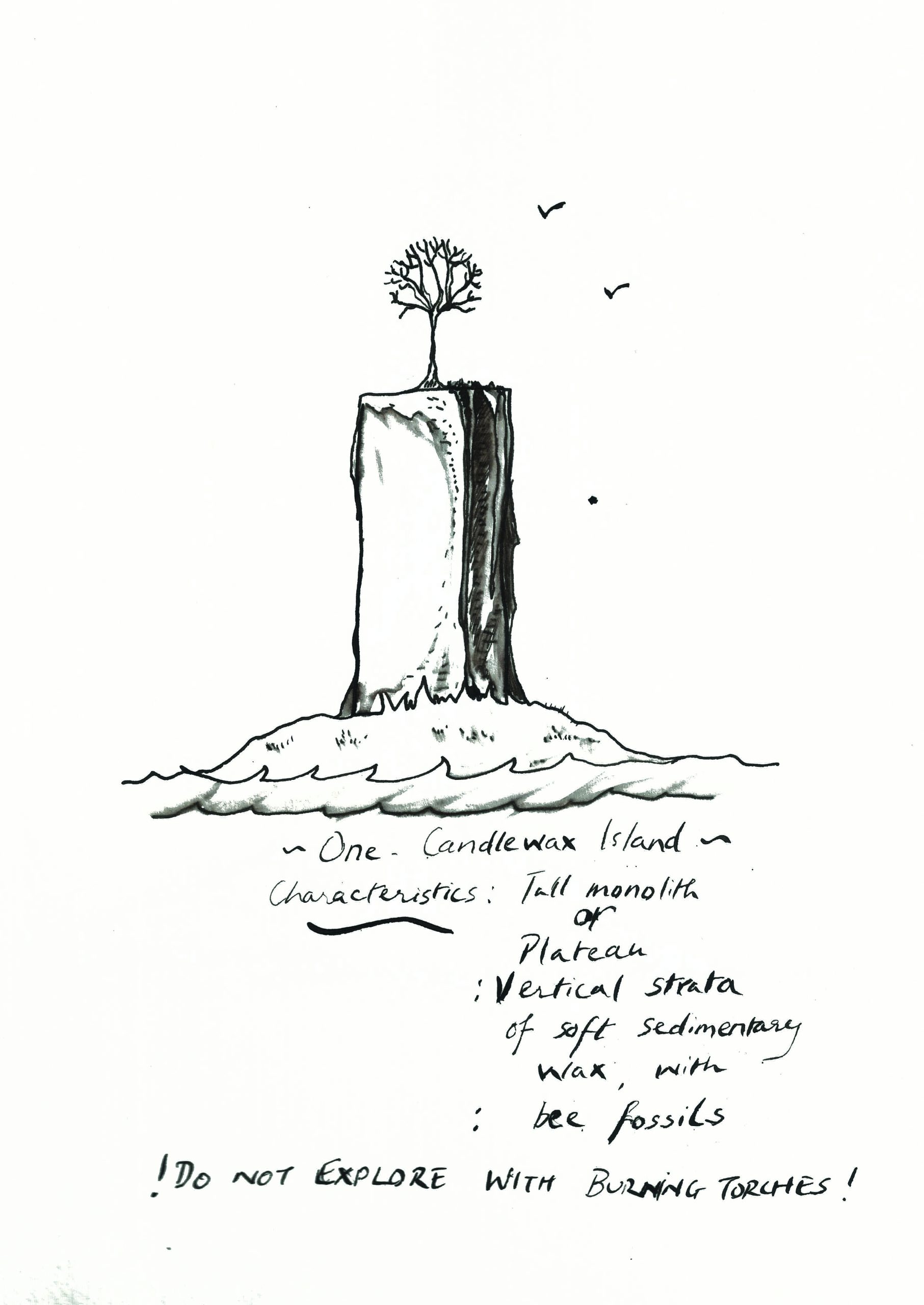

To redeem this deficiency, at 10 I wrote a little handbook for island explorers. Heavily influenced by my parents’ library of 17th -19th century naturalists and explorers, this was a manual for intrepid naturalists and discoverers, very much of the here-be-monsters genus. It contained a way to identify and classify islands, and not mistake them for continents, as Christopher Columbus did. I modelled my imagined islands after conventions of the genre of course, but also after walnut shells, spacecraft from Star Trek, funny hats and birds’ nests. The frontpiece though, was a trough-like depression of sunken nothingness, ringed by coral reefs that kept the sea out. This void-as-island was what I imagined the aftermath of an explosion to be.

From lost atolls, vanishing archipelagos, to mist-shrouded and obscure outcrops, the general instability and unknowability of islands has always been the stuff of books of adventure, to which I was also quite addicted as a juvenile. Insulated from the prosaic world outside, I spent my childhood happily marooned in my parents’ library. I already knew that only on islands would the likelihood of first discovery, of original encounter, of mapping the inconceivable be truly possible. Discovering a continent was to me not a revelation on par with the strange weirdness of islands like the West Indies, Galápagos, of the islands of the South Pacific. This silly guidebook was very much the awkward, faintly ludicrous imagining of a half-grown child, and is thankfully lost. But since I’m writing about it, exactly three decades later, here is a poor mnemonic reconstruction of a page.

Rao, Shubigi. Reconstructive drawing of lost handbook.

Medium: pen, ink and poor memory. 2015

And in the 30 years intervening between those first thoughts and this reconstructive scribble, this is what I think I know about the island:

The island is Singular, like the racialist ethnographic and anthropologic device employed when speculating upon the unfamiliar and unknown. It is the reduction of disorder and divergence to a solitary specific as representation of the native, the observed, the other. It is singular too, in its stubborn peculiarity, in how no one island is like another, or like anywhere else. It shares this conceit with every human ego, and so, being us but at the periphery, perhaps the Island is also the Id.

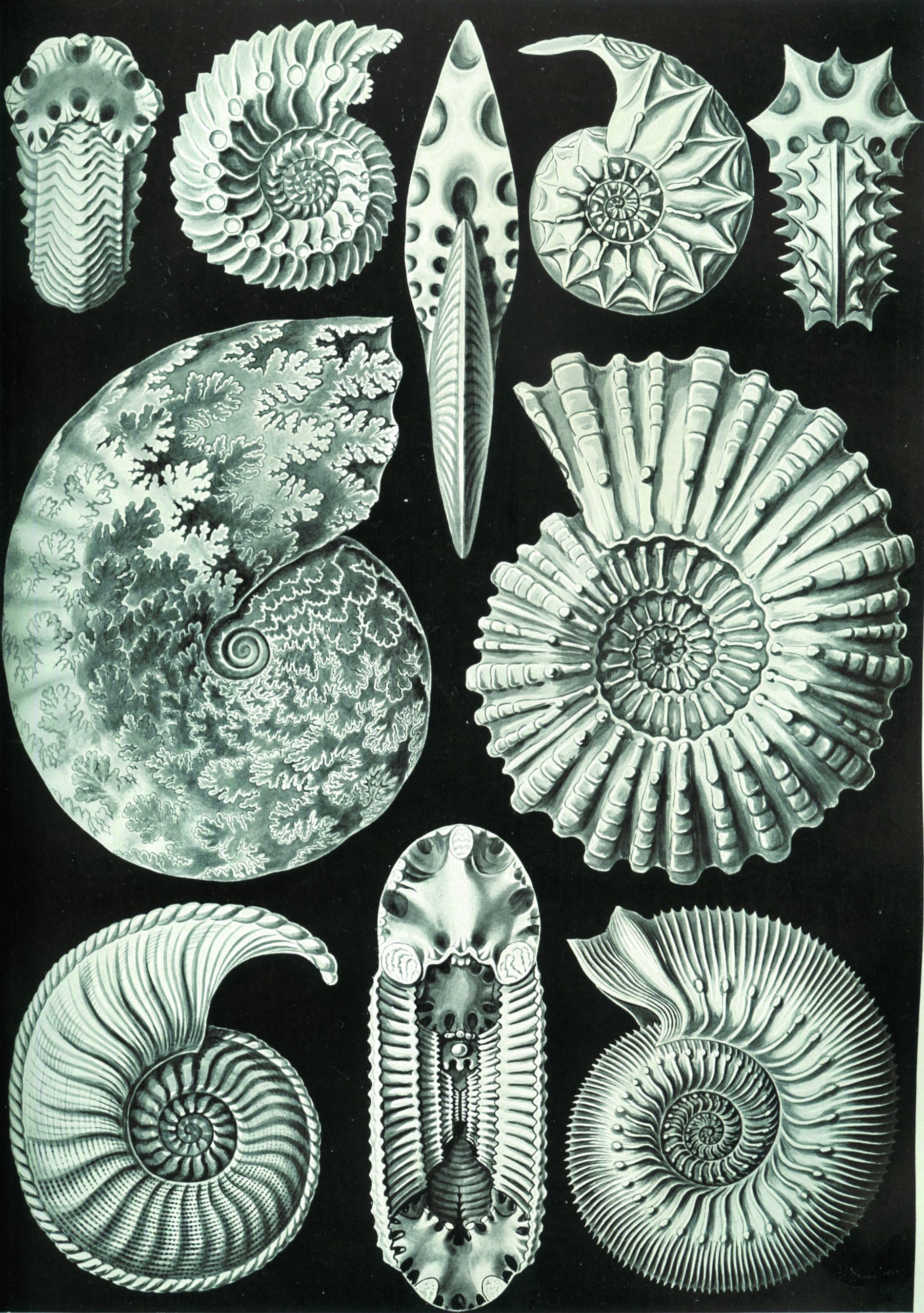

The island is our planet. It is also possible that there is no planet like our island Earth1. It is a microcosm of densely packed time, holding in its strata every accident, incident, upheaval, motion, and collision. Current continents were once islands, vast floating landmasses breaking apart, Pangea becoming Gondwanaland, the latter becoming India, pushing smaller unfortunate island strings out of its way, on its inexorable drift northwards to ram into Asia. The scar of that prehistoric collision is the Himalayas, which is where I grew up and where I found my first ammonite. Imprint, fossil of a prehistoric marine animal carried on that remorseless migration, 50 million years ago, marooned 3000 metres above sea level. The summit of Everest, the highest point on Earth, is composed of marine corals and limestone. The tectonic plates are still moving, and they were what triggered the deadly explosion of Krakatoa. Such is the story of our planet, the island. If its geology is compressed time, then its creatures are the offspring of migration and place. The island as we know it is on the margins. Breeding on its surface are the peculiar offshoots of its self-containment, and whatever stray embryonic-pods the wind and waves, deposits of guano, soles of shoes and even a spade2 may bring. Whether teeming or barren its animated life is as much a product of its anomalous inner geography as its latitude. It holds within it the knowledge of progression of all life, extinct and extant. And like our planet it is totality hot-housed in isolation, a blip in the immensity of time, an oddity floating in vast space.

Haeckel, Ernst. Kunstformen der Natur.

Leipzig und Wein: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, 1904.

Plate 44: Ammonitida

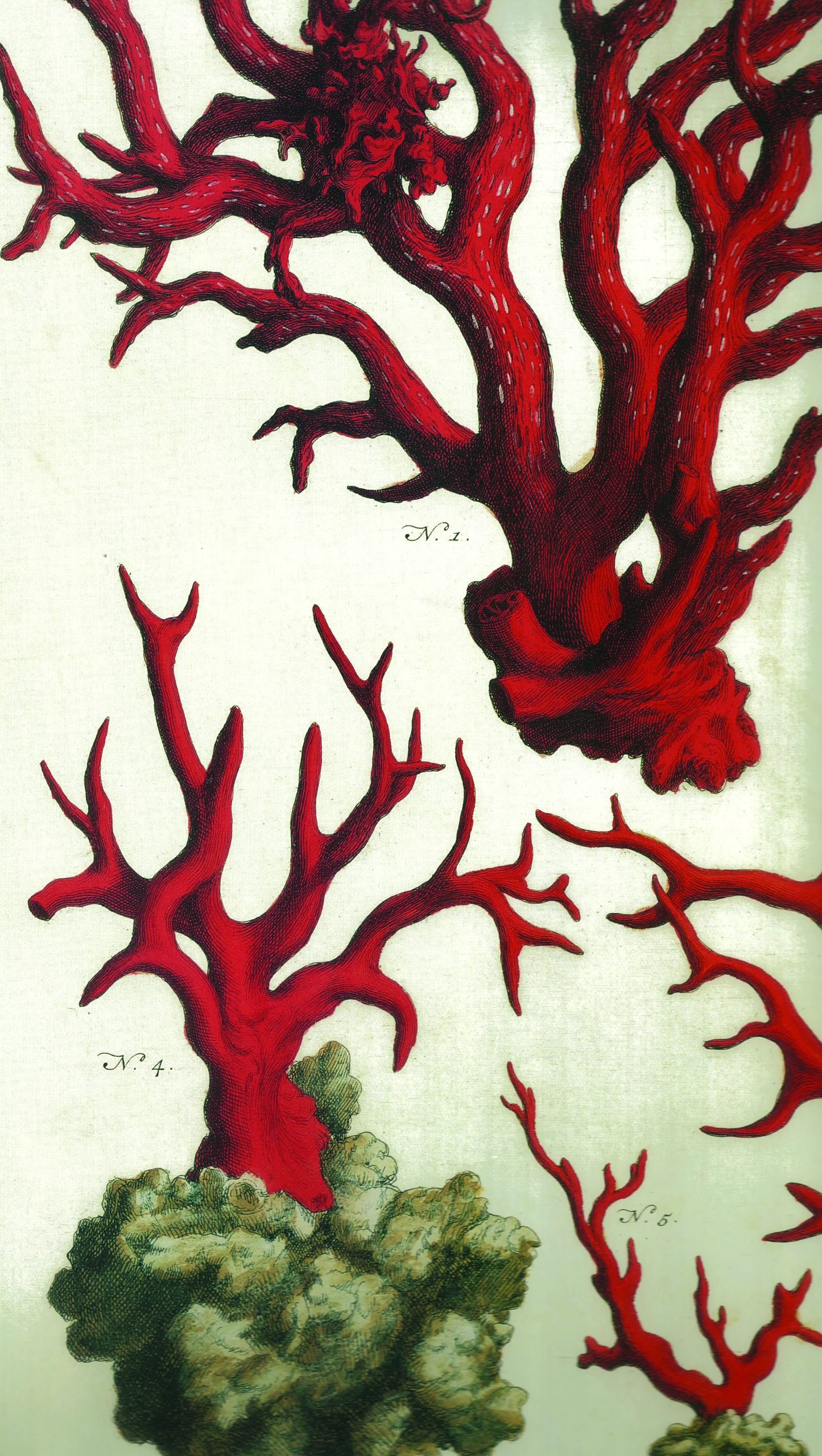

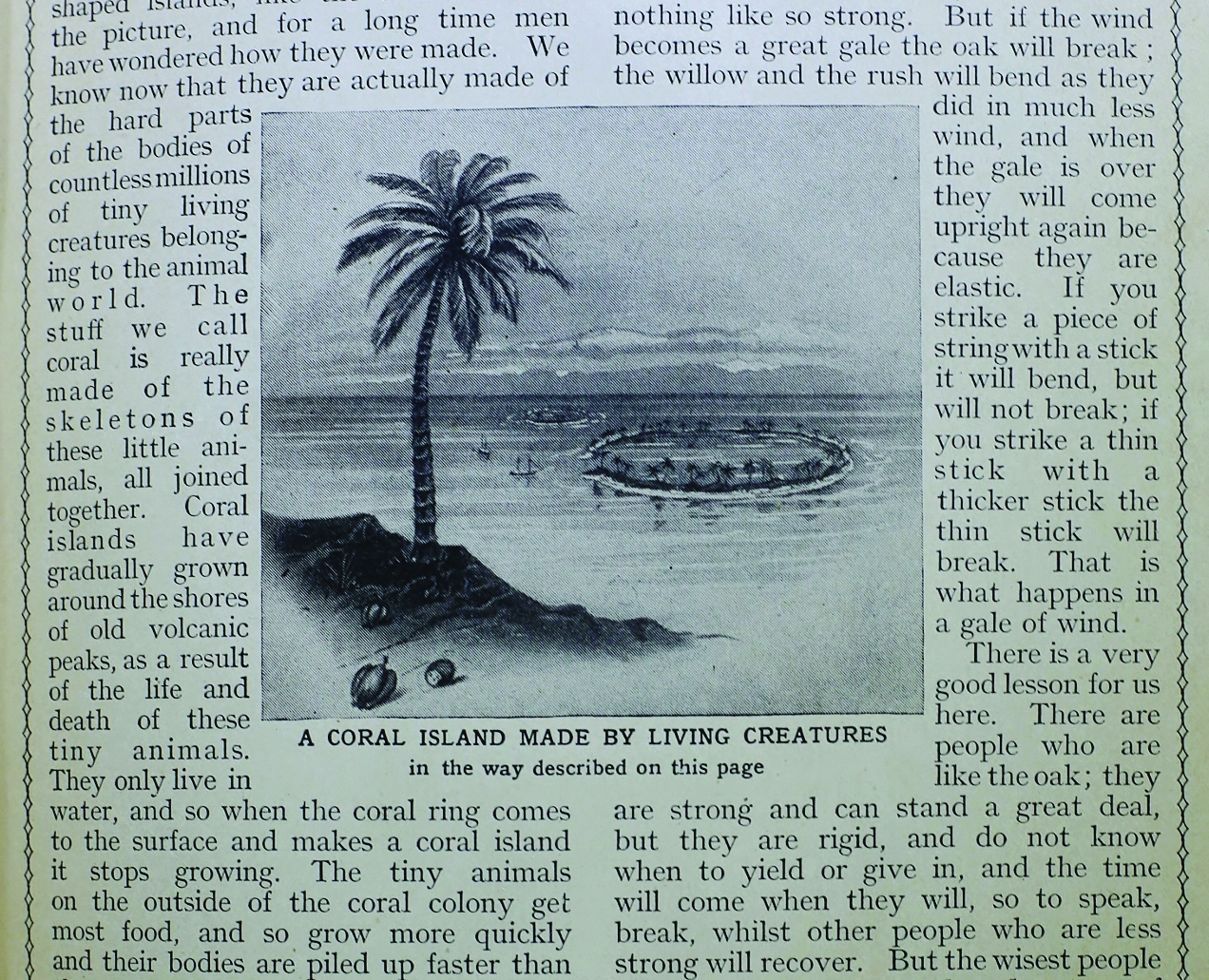

The island is cataclysm. Volcanic eruptions destroy in an instant, as they did in the case of Krakatoa. Underwater volcanic eruption, effusion and lava flows painstakingly accumulate till they emerge, sometimes as entire island chains. Anak Krakatoa is a prodigious child that grows 13 centimetres a week. Upheavals can take place over epochs, and are no less dramatic. Atolls, archipelago and reefs are not always volcanic or the outcrops of submerged islands. Even the Bikini atoll reefs, site of so much radioactive death-dealing were built on the fossilised remains of dead coral. Charles Darwin recognised that in the Tahitian reefs, and wrote his first scientific treatise on it. But before him was Johann Reinhold Forster, who a century earlier recognised that the atoll rings that lay just below the surface of the ocean, visible and fragile, were built solely of tiny animalcules, coral and other calcareous creatures that lay their foundations on the ocean floor, miniscule organisms growing in rings as bulwark against the ocean, tenaciously growing in layer upon layer, endeavouring for millennia to reach the light.

Seba, Albertus. Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description. 1734-36. Print of ‘Coral’.

Photographed by Shubigi Rao at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014

The island is out of time. We call our planet Earth when it is mostly water. We have islanded oceans from our consciousness, since we are terrestrial creatures.

Those islands that are far from territorial flexing may appear on maps but are largely immune to the daily mayhems of the continental human. Consider this too, that the out-of-time island has resisted easy demarcation, continental taxonomies and concerns. This island feels the diurnal and seasonal shifts more keenly, shifts that we have largely electrified and artificially cooled or heated away. And yet how far removed are we really? The highest mountains on earth were once shoreline. The Great Barrier Reef is mountain, submerged. The general instability of islands renders them risky propositions, even when deemed to be of strategic importance. The territorial claims of nations can find easy scapegoats in islands, even when they are rocky outcrops barely large enough to hold a flag-wielding human. We creep closer with our reclamations and reshaping of shorelines, foreign sand and soil suffocating coral reefs that never emerged to make it to island status, terraforming the sea into submission. We make bridges and causeways, and they are never enough. We make bombastic declamations like the Palm Jumeirah. But we forget that our demarcations and empires are merely attempts at staving off the inevitable. We are as out of time as the islands we claim.

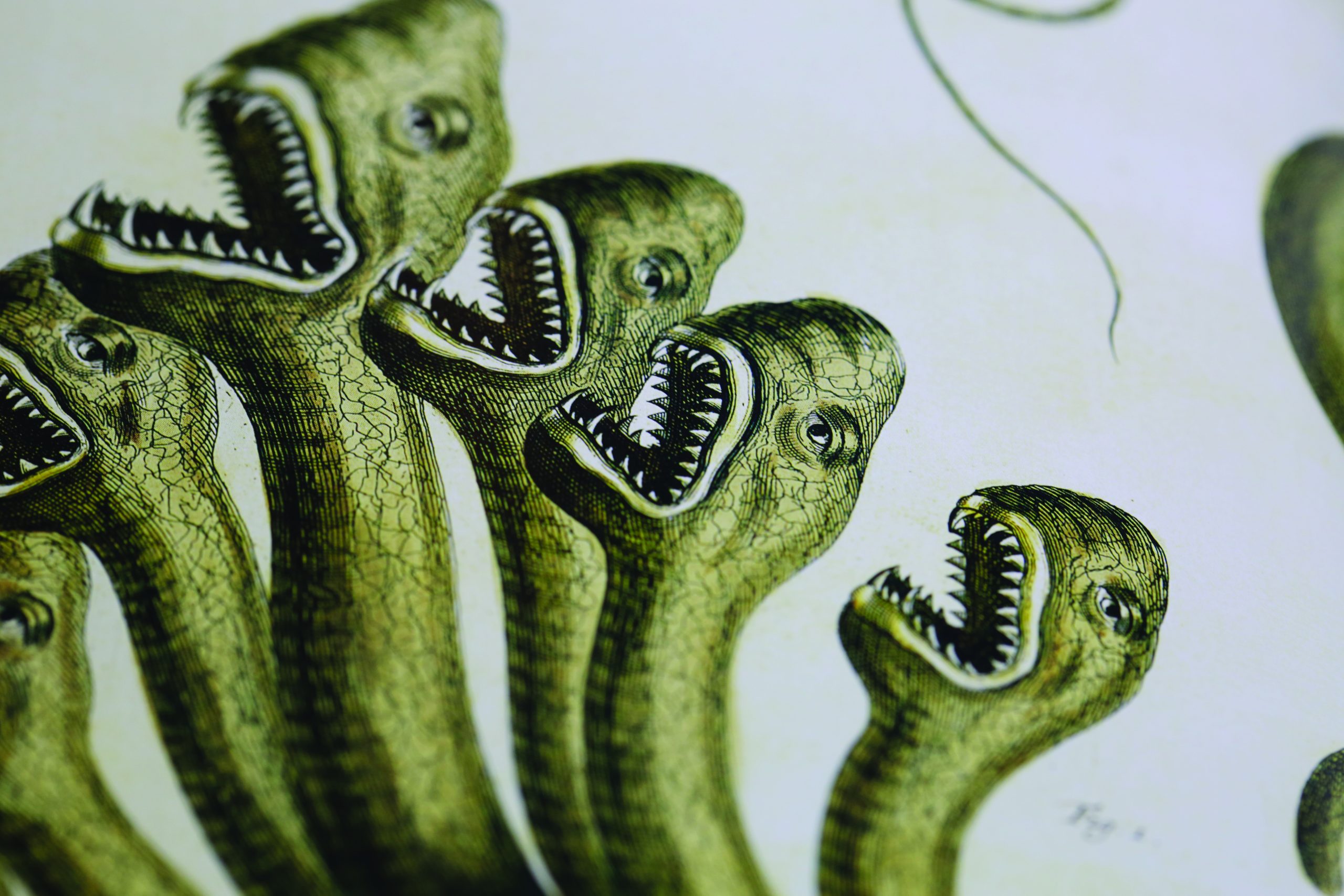

The island is an ideal/wrecking yard/clearing house/beachhead. It isn’t just the best place to test an unused nuclear arsenal. It is where the writer goes to summon the monstrously fantastic, whether of the pulpier variety (from the The Island of Doctor Moreau, and surely the horror of The Raft of the Medusa), or the impossibly abstract (Thomas More’s Utopia, is set on an island, after all). The island has played site and situation to countless scenarios, tales, fables, from utopian and dystopian, cautionary and moralistic, to fabulous and escapist. Popular culture would tell us that no good comes of breaching that ideal world. The island is only perfect when inviolate. Once we breach the hermetic immune system of the island it can rarely survive in its prior form. Still we dash ourselves on its rocks, beach ourselves on its sands, wash up on it shores. To be marooned (surely the desperate wish of every beleaguered washed-up writer) has a terminal allure, the possibility of untrammelled conjuring within that bounded frame, but piquant with the possibility of no return. From Crusoe to Cristo, the island has been set piece, narrative device, analogue for travail and struggle. Shakespeare frequently hurled his characters’ ships on rocks, forcing their reinvention. All our literary shipwrecks are the dashing of aspirations, of dramatic turns in the narrative. If the idea of a shipwreck seems laughably quaint in the contemporary, think of the appositely named Lost, where the island provides the setting for an outrageous, thoroughly implausible, infuriating and completely addictive set of time- and place-warping situations (at one point the island snaps out of existence to reappear elsewhere, like the Slavic Buyan), intermeshing contradictory timelines and narrative, impossible characters (one being composed of well, malevolent smoke). As a writer, try pitching that, sans island, to a TV production studio or channel. To me the anxiety of Lost had a distinctly nuclear-ticking-clock flavour, where the inexorable countdown always reset, and the ever-present unidentifiable menace was the constant, curiously unreal spectre of MAD.3 The island of Lost was a Cold War relic, because islands are where we rear our monsters, even the dead ones. The rejuvenation of the Jurassic had to occur on an island and over three sequels no less, with a fourth due this year because apparently we can never have enough of giant lizards on islands. It is on islands that we find our King Kongs and we inevitably, foolishly import them into the mainland with justifiably dire consequences. Sometimes they import themselves, as barbed stabs of our consciences, like Godzilla and other kaiju. Invariably they are larger than life, because only on islands thar still be monsters, and as Lord of the Flies showed us, frequently those monsters be we.

Seba, Albertus. Locupletissimi rerum naturalium thesauri accurata description.

1734-36. Print of ‘Seven headed hydra’.

Photographed by Shubigi Rao at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014

The island is epiphany myth-maker. The island is the X marked on a map, it is always the site of buried treasure, bodies and secrets. Perhaps the biggest secret treasure to be found was in the Galápagos. The legendary voyage of the HMS Beagle still captures popular imagination, and the finches of the Galápagos will always credited as having triggered Darwin’s epiphany. Like all stories of secrets and treasure it perpetuates a falsehood, that of the Eureka moment being the turning point in great endeavour. That buried treasure is discovered in a cinematic moment of inspiration belies the actual labour and intensive study. The 19th century Dutch naturalist Maria Sibylla Merina’s illustrated masterpiece on metamorphosis in insects was the outcome of living in Surinam. In Darwin’s case, after the famous Beagle voyage it took two decades of painstaking work, tackling irreconcilable, irreducible and prevailing ideas, of intensive study into disparate subjects that led to the development of his theories. Leonard Mlodinow mentions one by-product of his output being a 700-page monograph on the lowly barnacle. And yet it is telling that to formulate the story of all life on our planet, Darwin (and Alfred Russel Wallace in the Malay Archipelago) had to read the island to comprehend the mainland.

Merian, Maria Sibylla. Over de voortteeling en wonderbaerlyke

veranderingen der Surinaamsche insecten. Amsterdam, 1705.

Film still by Shubigi Rao, at Artis Library Amsterdam, 2014.

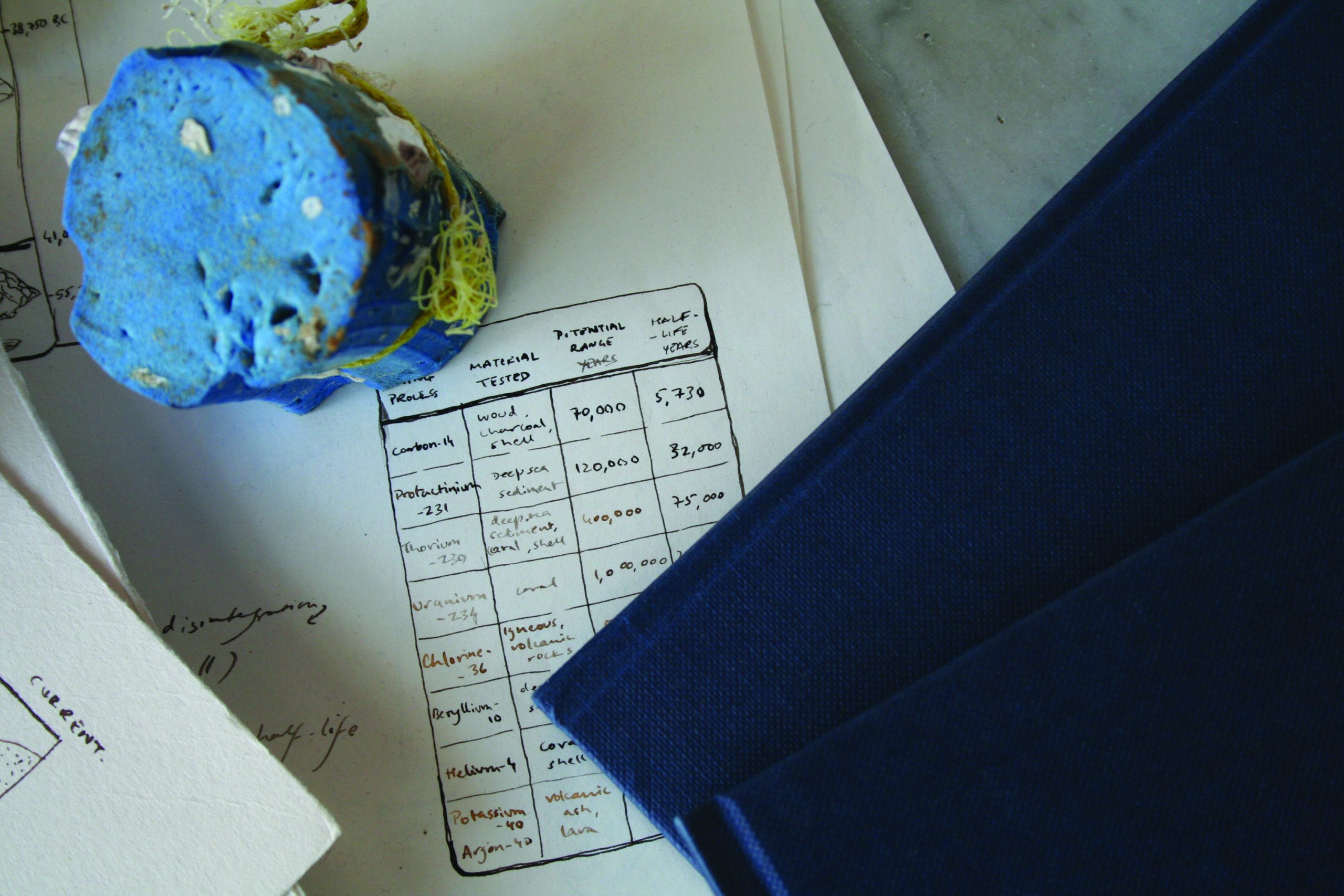

Barnacled artefact collected on East Coast of Singapore in 2003 by Shubigi Rao,

pictured here with notes and observations. Collection of Shubigi Rao.

Photo courtesy of Michael Lee

The island is bewitched. Cargo cults, cannibals and cooking-pot missionaries.

The island is a gag. The default sites for nuclear tests are the Nevada desert and the atoll – the deserted and the island. These are the tired tropes of poor interview questions and hoary jokes, and countless cartoons with a single coconut palm and bearded castaway. It is situation comedy at its simplest and yet most enduring.

Mee, Arthur; Thompson, Holland. The Book of Knowledge.

London: The Educational Book Co. 1918. Vol. 4, p 921

‘Islands made by coral animals’.

Collection of Shubigi Rao

The island is our brain. There are many realms left to explore – the vast ocean seabed with its bizarre creatures of the deep and teeming microbial life, the immeasurable universe, and the inscrutabilities of the human brain. This floating walnut, dreaming in the sun, with its insular climate and life, is a self-contained bubble yet sensitive to all stimuli that lap up on its shores. It is the repository where our worst fears and our escape plans cohabit. Lush and arid all at once, our brains grow rings of sharp reefs as we mature, so that it is only when we identify ourselves as discrete, when we recognise the isolation of our carefully maintained inner climate that we are truly, and finally adult.

The island is language. Discrete and idiomatic, it develops its own peculiar grammar, slippery dipthongs and plosive sounds, and it resists easy translation. The forked tongue of the natives of fabled Taprobane was divided such that “with one part they talk to one person, with the other they talk to another”4. The colloquialisms of the Galápagos have entered our vernacular, even as we wreak havoc on theirs. The 400 remaining Jarawa of the Andaman Islands call themselves aong or ‘people’, but to their traditional enemies Järawa means ‘foreigner’, and that is how we know them. The animated patois of island life is the curious idiosyncrasy of the Australian marsupial, the oxymoron of the flightless bird, the preposterous absurdity of the blue-footed booby, the mythic genealogy of the komodo, the irrational idiom of the duck-billed platypus, and the indecipherable metaphor of the Singapura Merlion.

The island is memento. Here in Singapore, we are the Island, but our 60 stepsisters are also islands, though we sometime forget their names. These outcrops, addenda to the main-Island, offer possibilities of what-was and what-we-probably-miss-but-can’t-quite-name. Some offer day-trips to nostalgia, epigrammatic non-airconditioned escapes to be Instagrammed when back on the main/is/land. Some can be cycled-through like a visiting dignitary touring the provinces, marvelling at the trees (fruit growing! durians!), fearful of its feral fauna, exclaiming at the ‘simple lives’ of its natives. Pulau Semakau now offers recreational activities, but I hear that no one is nostalgic for it, this future midden-heap, a more densely packed, stratified snapshot of the cremated detritus of our lives.

The island is sinking. And with all things finite and doomed it carries its own mythology and wishful imaginings, of paradisiac absolutes like Atlantis, and the hellish come-uppances of morality tales, sinking into that long sleep of the deep. One wonders how a sunken Venice would be reimagined, mythicised in future lore. Would the biannual descent of the hedonists of the art world be held responsible for its punishment by submergence? Would disaster tourism prevail, and its piazzas be thronged with rubberneckers in rubber-suits? Would its lost frescoes, domes and sighing bridges become an underwater theme park for intrepid honeymooners? Would it be a cautionary tale of the castles-built-on-sand variety, of building on terra that is barely firma? Or would it perhaps be of the foolish but undeniably Romantic human spirit railing against the inevitable tide?

Garbage on East Coast beach, Singapore 2003. Photos courtesy of Shubigi Rao

The island is mobile. India was once an island (and still moves north at about an inch a year), which makes me an islander twice over. There was the perpetually peripatetic, mythic Taprobane, a cartographic anomaly, an ambulatory Never-land till it was banished by modern thought, along with other phantom islands. The legendary Sargasso Sea is now rivalled by massive floating islands of micro-plastic and other garbage in the Pacific. There have also been sightings of one composed solely of ping-pong balls, and another of Lego pieces, and of rubber ducks that have been sporadically washing up on beaches since the 1990s. Not all our new mobile islands are flotsam – we have (Mobil) oilrigs, floating platforms, carriers and patrolling navies. Colossal container ships, super tankers too massive to dock, waiting patiently offshore, occluding the horizon all along Singapore’s eastern shore. I hear that modern shipping is a marvel of technological navigation. I also hear that if you’re a castaway, the likelihood of being crushed under the hull is higher than being rescued, because you are too small to be sighted on today’s impressive navigation systems. When I think of stowaways I think of Darwin’s barnacle, the scourge of shipping, and how the increasing acidification of the oceans thanks to fossil-fuel use will result in its destruction. I think of how the barnacle is the catalyst of its own obliteration – by reducing speeds, ships are forced to burn more fuel, further acidifying the oceans. This may be one of the very few happy outcomes of climate change, another inexorable force that will eventually submerge islands, make islands out of lowland, and set people and cultures adrift and unmoored. The Maldives will probably cease to be islands in my lifetime. We now have a neologism – climate-refugees.

The island is death. There have always been floating islands of people. The year I was born, they began to call them boat-people, because to us of the mainland they are stateless and therefore nameless, and, like the island, they are marginal, marooned and are all too often items to be quarantined. There are people lost at sea, not far offshore from where I write this in my territorial bubble. They say Singapore is also an island, and therefore too small to allow landfall. Malaysia and Indonesia will tow in these islands of the disposed, confine them for a year and then, resettle them elsewhere or repatriate them to the hell they fled. As I write this I think about the news today, where they discovered that those who had previously survived months of being marooned at seas finally made landfall, only to be sunk in mass graves.

The island is organism, single-celled. The island is interlude. The island is playground. The island is prison, penal colony. The island is escape. The island is freedom. The island is knowledge, a library. The island is a lie. And like all impossible, irresistible fictions, unknowable and perfect, lost in the instant it is found, the Island is singular.