In recent years there has been a renewed interest in the ’idea’ of Yugoslavia,1 not only in our region, but also globally. This interest has to do primarily with specific Yugoslav socialism as well as the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of which Yugoslavia was a key member. The reasons are many: disillusions in the current global world order, especially rapid neo-liberal globalisation which has created huge problems; inequality, the rise of new forms of dependency (economic, political); the rise of right-wing politics and fascisms; and so on.

The NAM represented, at least until the 1980s, a significant “rupture” on the global level—an attempt at an alternative mondialisation, and a desire to create a more just, equal and peaceful world order. Yugoslavia was a special case in this constellation, it helped to bring non-colonial Europe into the grouping. Unlike many colonial narratives, Yugoslavia had never asserted itself as a nation or culture that worked to ‘civilise’ others.2 Instead, it cultivated and maintained the notion of itself as the culture/nation that aimed to help others establish a position in a role that had yet to be created and clearly defined (the ‘older brother’ paradigm, which is also problematic from today’s perspective). Yugoslavia’s socialist, anti-imperial revolution had a lot in common with anti-colonial ones which made the Yugoslav case of emancipation particularly significant. Being one of the key members in the NAM, Yugoslavia supported global anti-colonial struggles3 not only politically but also economically and culturally.

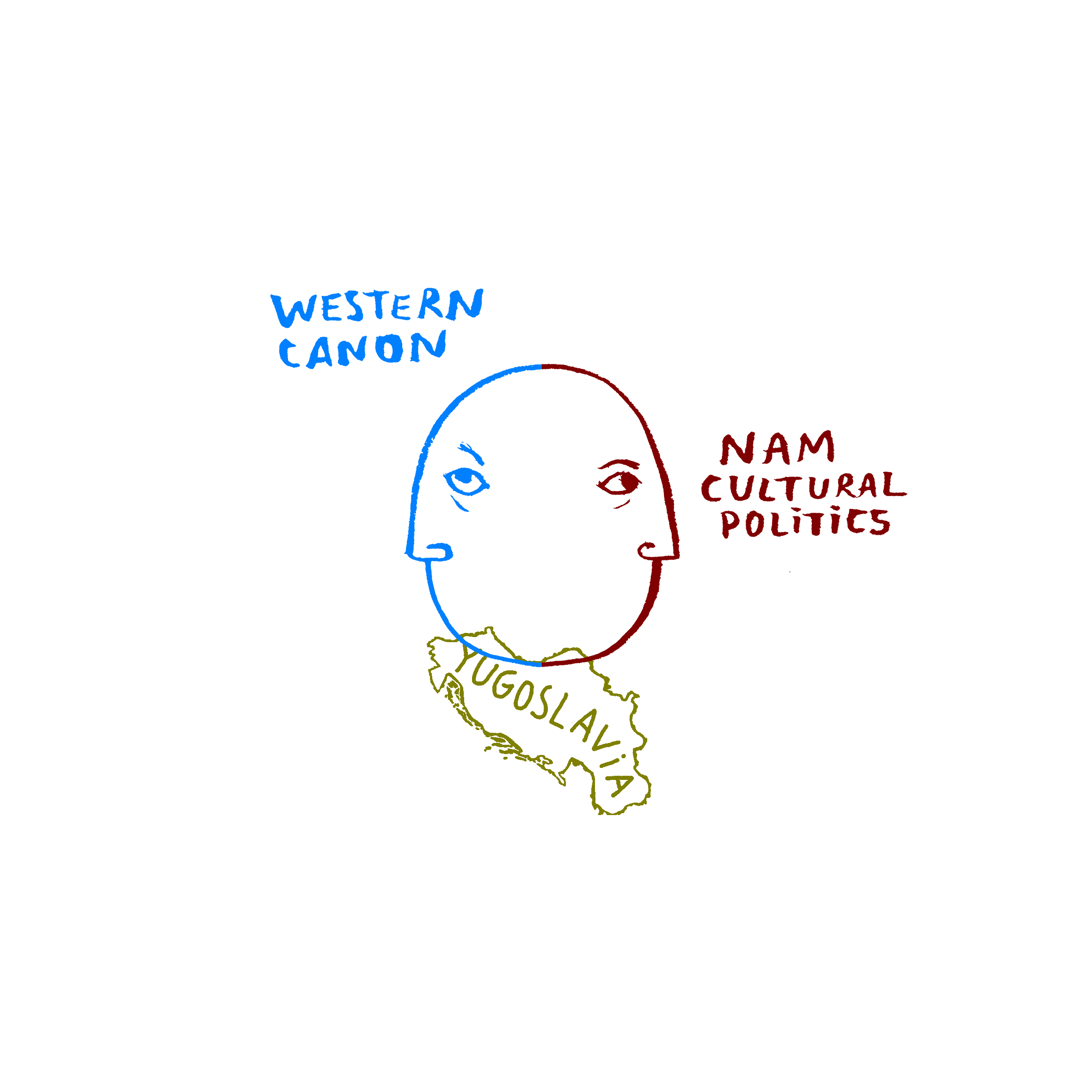

Art and culture played an important role in the NAM, even though comparatively little is known about this today. The reason is that after the Second World War, the main orientation in arts and culture in many non-aligned (decolonised, newly independent) countries as well as in Yugoslavia was the one following the Western epistemic canon.4 The other non-western ‘story’ comprised of various “provincialised modernisms,”5 and heterogeneous expressions propagated ideas that were often in line with similar issues that non-alignment addressed. Such ideas were, for example, the questioning of cultural imperialism, restitution and epistemic colonialism. NAM’s cultural politics from the beginning specifically encouraged cultural diversity and cultural hybridity. Western (European) cultural heritage was to be understood in terms of “juxtaposition”6; this heritage would be interwoven with and into the living culture of the colonised, and would not simply be repeated under new (political) circumstances. For this reason, a “cross-national appreciation for cultural heritages” and a local-to-local approach was extremely important.

Jugoslavija (Yugoslavia) booklet from the series

Non-aligned and the Non-alignment

published by Rad, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1975

Private archives

Yugoslavia might be a good case-study for this cultural dilemma. On one hand, Western canons were widely accepted in the art circles and on the other, non-Western ones were politically stimulated through various cultural policies connected to the NAM. However, they were stimulated without a deeper understanding of what “other” modernisms really meant, as it is clear from reports, texts and concrete cases such as exhibitions and other museological contexts of that era. But in order to better understand this specific phenomenon we first need to go at least a hundred years back.

“In 1963 all Africa must be free!”7

In the late 1920s, there was already a growing fascination among Yugoslavia’s cultural circles with faraway places. However, few Yugoslavs travelled to exotic places, largely because Yugoslavia was not a colonial country and as such had no colonial experience. There were exceptions; there were Yugoslavs studying in France who showed a particular interest in Africa; many of them belonged to the surrealist circles, including Rastko Petrović, an avant-garde writer, poet and diplomat who travelled to Western Africa in 1929. His book Africa8 is a record of that journey. The book was in some ways a typical product of the era, written from the perspective of a white European male, based on pre-conceived colonial knowledge and stereotypes about Africa. Petrović nevertheless attempted to answer the question what it meant to be an “European Other” in Africa; or to put it in a somewhat larger frame, what it meant at the time to be a European “from a margin of European modernity.” Another important Paris encounter unfolded in 1934, when Petar Guberina, a PhD student of linguistics at the Sorbonne, met Aimé Césaire.9 Guberina invited Césaire to his native city Šibenik that same year, and it was there that Césaire started writing his famous epic poem Notebook of a Return to the Native Land,10 which was one of the first expressions of the concept of negritude. Not surprisingly, the preface was written by Guberina. Another figure in that circle was Léopold Senghor, who later became President of Senegal and travelled to Yugoslavia on an official state visit in 1975. In his speech at the First International Congress of Black Writers in Paris in 1956,11 he pointed out: “Cultural liberation is the condition sine qua non of political liberation.” A few years later Guberina published a book, Following the Black African Culture, in which many of Césaire’s and Senghor’s thoughts on culture resonated. In what sounded much like Senghor’s Paris speech, he wrote: “Black cultural workers, although there were few, have manifested a multifaceted function of culture and used it as a powerful weapon against colonisation. Cultural workers have become political workers and vice versa.”12

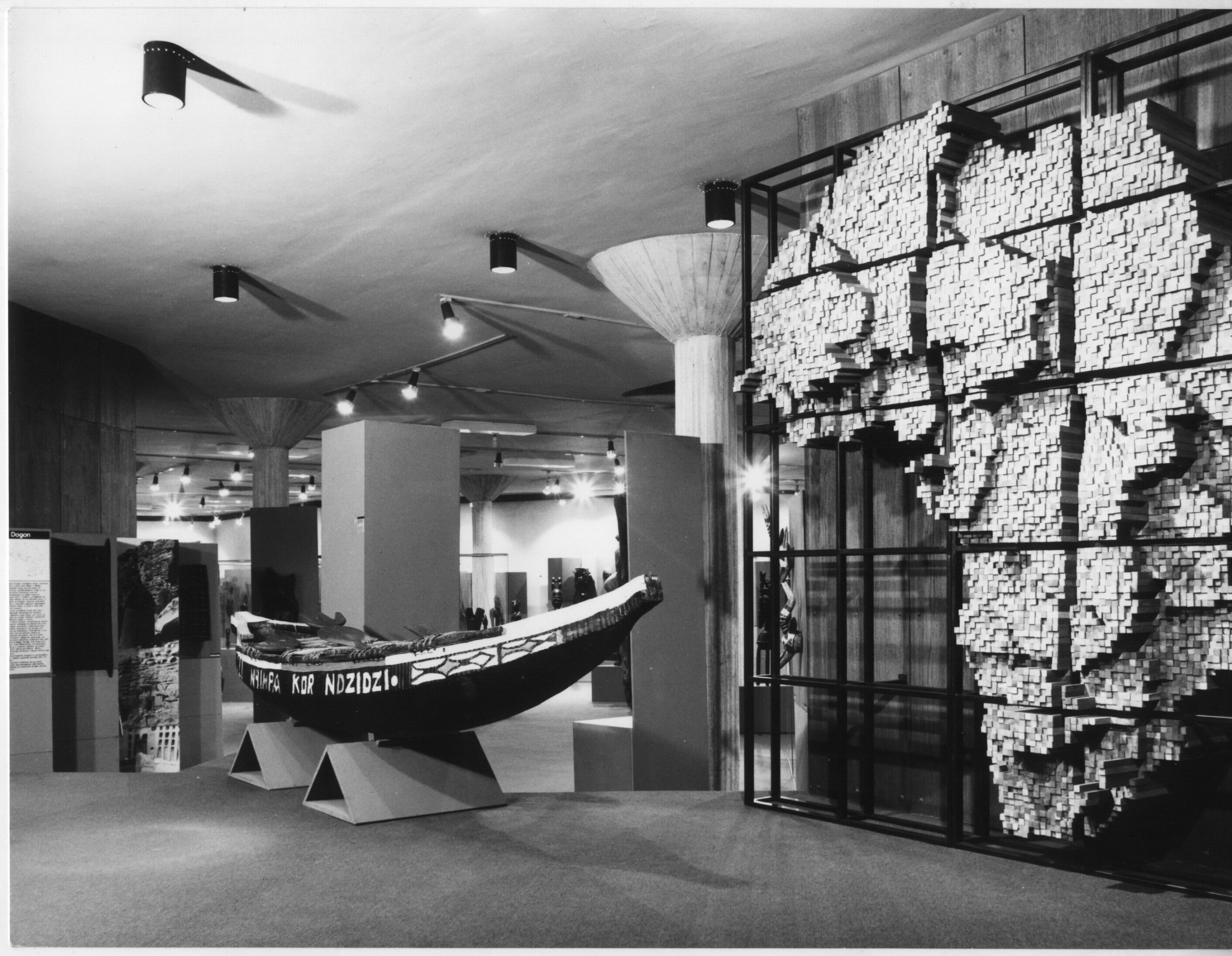

The permanent display of the Museum of African Art (MAA)—

the Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar Collection, 1977

Photographed by Branko Kosić. Photo courtesy of the Museum of African Art

—the Veda and Dr. Zdravko Pečar Collection, Belgrade (MAA)

The MAA permanent display, concept by Jelena Aranđjelović Lazić,

design by Saveta and Slobodan Mašić, 1977

MAA Photo Archives

It was the 1960s in particular, that saw the rebirth of a specific travel literature about “exotic places,” the most prominent example of which was the work of Oskar Davičo—not surprisingly another surrealist writer and politician who had visited Western Africa to prepare for a meeting of the NAM. He wrote a book about the journey called Black on White, in which he analysed African post-colonial societies at the time. Davičo, a very different observer than Petrović, did not want to be seen as a white man in Africa. Moreover, he was even ashamed of his whiteness, saying that if he could change the colour of his skin he would have done so without regret: “Yes, I am white, that is all the passers-by see. If only I could wear my country’s history digest on my lapel!”13

A year later, travel journalist Dušan Savnik began his book Black Continent with an exclamation: “In 1963 all Africa must be free!”14

To make the Third World a place from which to speak.15

Already at the 1956 UNESCO16 conference in New Delhi, a great importance was put on “dissemination of art works of contemporary artists.”17 Interestingly, the focus of such cooperation was between “the peoples and nations of the Orient and the Occident.”18

A few years later, the 1964 report of Heads of State participating at the second Non-Aligned Conference in Cairo considered cultural equality one of the important principles of the NAM, at the same time recognising that many cultures were suppressed under colonial domination and that international understanding required a rehabilitation of these cultures. In the Colombo Resolution in 1976, emphasis was placed on restitution; the members requested restitution of works of art to the countries from which they had been expropriated.19 And at the conference in Havana in 1979, Josip Broz Tito spoke of the resolute struggle for decolonisation in the field of culture. The Havana Declaration also emphasised cooperation among the non-aligned and developing countries, as well as: “…better cultural acquaintance; and the exchange and enrichment of national cultures for the benefit of over-all social development and progress, for full national emancipation and independence, for greater understanding among the peoples and for peace in the world.”20 The Delhi Declaration in 1983 focused more specifically on cultural heritage and its preservation, as well as on cooperation in culture between the NAM members.

In Yugoslavia, a special committee was established after the Second World War called the Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, which arranged exhibitions outside Yugoslavia’s borders and was chaired by the surrealist writer and artist Marko Ristić. Cultural conventions and programs of cultural cooperation included not only Western and Eastern Europe, but also non-aligned countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. These exchanges touched on all levels of cultural production. Cultural cooperation between the non-aligned countries was based on conventions on culture and programs of cultural collaboration.

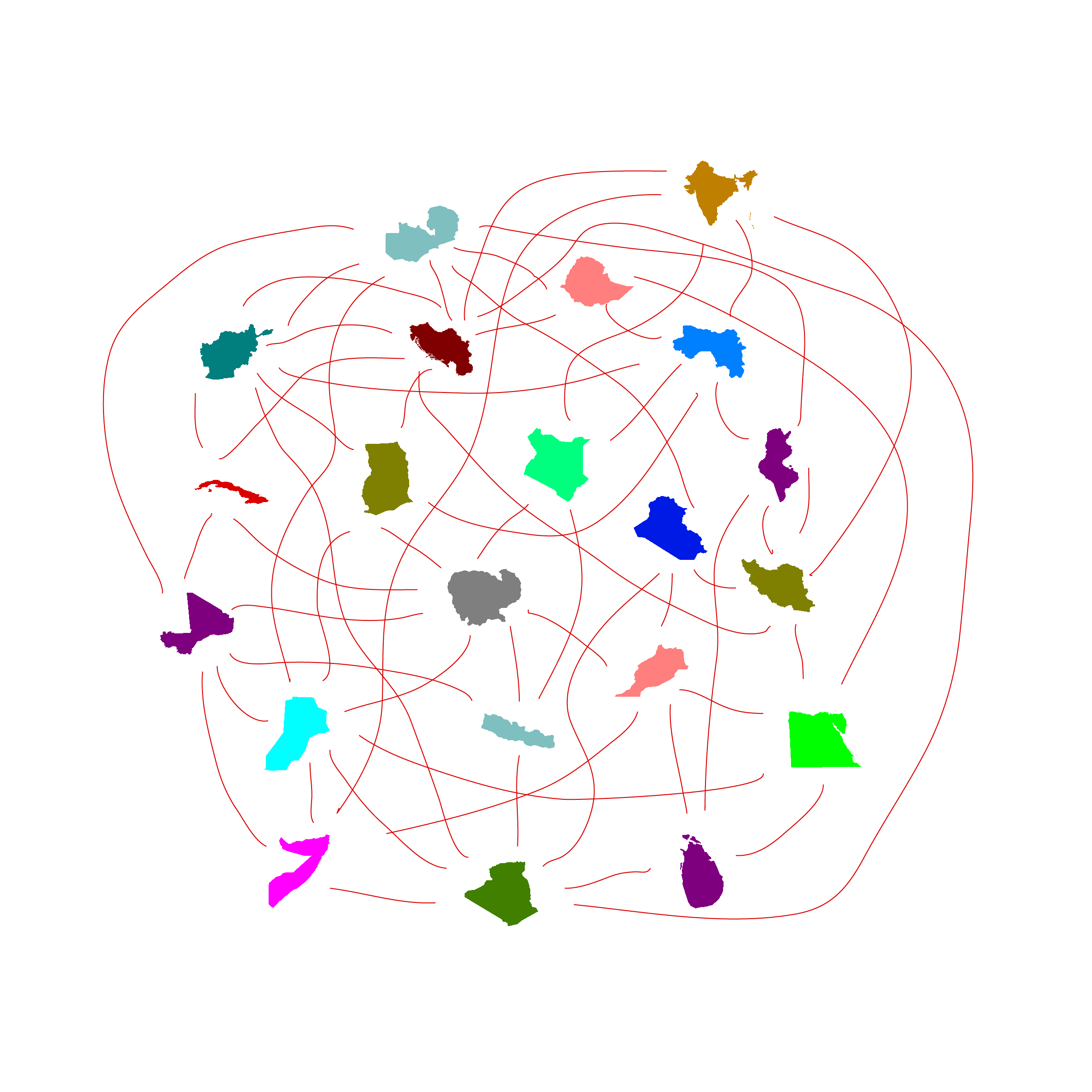

Yugoslavia, for example, has signed agreements with 56 non-aligned members and observers. In addition, between the 1960s and 1980s many new biennials opened throughout the non-aligned world signifying a different kind of cultural exchange: Biennial of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana; Triennale-India in New Delhi; Coltejer Art Biennial in Colombia; International Art Biennale in Valparaíso; Asian Art Biennale Bangladesh in Chile; Biennial of Arab Art in Baghdad, Iraq; Havana Biennial in Cuba and others.

Yugoslavia propagated its ideology and culture globally on the basis of the formula: specific modernism(s) (based on Western canons) + Yugoslav socialism21 = emancipatory politics. It was at the same time an articulation of an idea, and an attempt to show the world how it is possible to direct one’s own modernisation processes.

The NAM’s cultural politics were intertwined into Yugoslav cultural politics but in reality those other modernisms and art expressions were never of significant consideration in Yugoslav society nor were they part of the museological deliberations. There existed exceptions in architecture and urban planning but also with the establishment of some new collections, institutions and exhibitions.

“Art of the World” in Yugoslavia

As mentioned already in the first chapter, Yugoslavia had special relations with the newly independent countries in Africa and Asia from the late 1950s. President Tito often travelled to those countries on so called “Journeys of Peace.” A particularly significant one was his visit to Western African countries on the Galeb (Seagull) boat in 1961, not as a conqueror, but to support the independence of post-colonial states. These travels consequently acquired a strong economic dimension and created new spheres of interest and exchange among countries of the NAM. Intense economic collaboration at first included Yugoslav construction companies working on projects in Africa and the Middle East—companies that had sprung up as a consequence of the rapid urbanisation of Yugoslavia after the Second World War. Probably the largest of them was the Energoprojekt22 construction company from Belgrade that operated in 50 non-aligned countries, designing and building infrastructure (hydropower plants, irrigation systems, and electricity networks) and buildings (mostly conference halls, office buildings, hotels, etc). Constructing companies provided everything “from design to construction,” including architecture and urban planning. Such examples, as mentioned, were projects in various African and Arab non-aligned countries, like Energoprojekt’s Lagos International Trade Fair (1974-77), where architects combined specific (Yugoslav) modernism with tropical modernism and the local contexts.

Dubravka Sekulić’s project on Energoprojekt. Exhibition view

Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija

Dubravka Sekulić’s project on Energoprojekt. Exhibition view

Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija

Map (Asia) of Yugoslavia’s international collaboration in culture with developing countries

Researcher: Teja Merhar, map design: Djordje Balmazović

Project for the Southern Constellations: Poetics of the Non-Aligned

Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Cover of the catalogue for the travelling exhibition contemporary yugoslav prints, 1976

Moderna galerija Archives

Exhibition view. Southern Constellations: The Poetics of the Non-Aligned. Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 2019

Left to right: the works of Rafiqun Nabi (Bangladesh), Cho Geumsoo (North Korea),

Elba Jimenez (Nicaragua), and Agnes Clara Ovando Sans De Franck (Bolivia)

Photo: Dejan Habicht, Moderna galerija

Exchanges of all sorts also happened in the field of the arts and education: students from non-aligned countries came to study in Yugoslavia; museums acquired various artefacts; and some institutions even opened anew. The Museum of African Art which opened in Belgrade in 1977 as a result of this ideological and political climate is a typical case: even though the predominant discourse of the time of its establishment was anticolonial, the methodologies and procedures were almost completely adopted from similar institutions in the West.23

But the earliest example of cultural exchange is the founding of International Exhibitions of Graphic Prints in Ljubljana (then Yugoslavia) in 1955. The director of Moderna galerija, Zoran Kržišnik, formed a committee for the first international exhibition, which drew up the guidelines for the biennial exhibitions to follow. The purpose of founding a Biennial was to pave the way for establishing contacts globally, introduce abstraction into Yugoslav art, and prove that even “art can be an instrument of liberalisation.” The idea was to invite artists from all of the countries with which Yugoslavia had cultural or political relations. The Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts was to be a practical example of Yugoslavia’s cultural diplomacy and the cultural policies of the NAM which Yugoslavia followed, parallel to balancing its position between the Western and Eastern power blocs. The Ljubljana Biennial’s approach to acquiring works for the exhibitions was twofold: on the one hand, the Biennial juries made their own selections to get the best representatives of e.g. the School of Paris; on the other, some countries were offered direct invitations to present whatever they wanted, without any interference in their selections. As a result, the Biennial exhibited “basically everything, the whole world,” especially after the first conference of non-aligned countries in 1961. The selection process involved competent juries, which largely consisted of curators and critics from the West, such as Pierre Restany, Harald Szeemann, Riva Castelmann, William Lieberman, but also Ryszard Stanisławski from Lodz and Jorge Glusberg from Buenos Aires. But although enamoured with Western ideals and following its pragmatic political agenda, the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts was nonetheless globally one of the first non-bloc art events at the time of the Cold War divisions, putting forward a model for a peaceful coexistence of the first, second and third worlds—if only in art and culture.

5th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 1963

Jury members: Mieczyslaw Porebski, William S. Lieberman, Zoran Kržišnik, Walter Koschatzky, Jacques Lassaigne, Umbro Apollonio, Aleksej Fjodorov-Davidov

Photo: Moderna galerija Photo Archives

13th International Biennial of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 1979

President Luís Cabral of Guinea-Bissau (right) visits the exhibition

Photo: Moderna galerija Photo Archives

6th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 1965

Flags of the participating countries in front of the museum

Photo: Moderna galerija Photo Archives

Exhibition view. 8th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts,

Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 1969

Photo: Moderna galerija Photo Archives

In 1984, The Josip Broz Tito Gallery for the Art of the Non-Aligned Countries was inaugurated in then Titograd, Yugoslavia, with the aim to collect, preserve and present the arts and cultures of the non-aligned countries. It was the only art institution established directly under the auspices of the NAM. This was entrenched in the document adopted at the 8th Summit in Harare, Zimbabwe, a couple of years later, where the gallery was to become a common institution for all of the NAM countries. The activities of the gallery were many: alongside collecting works from the NAM countries they also organised exhibitions, symposia and residencies, and produced publications and documentary films. Works from the collection were also shown in Harare, Lusaka, Dar es Salaam, Delhi, Cairo and elsewhere.

Unfortunately, their aim to create a Triennial of Art from the NAM countries was never realised owing to the wars in Yugoslavia in the 1990s. It appears though that there was something of a lack of understanding of such “provincialised modernisms” in Yugoslavia at the time, and a special lack of firmer positions regarding other cultures in relation to (Western) modernism. Some prominent Yugoslav art historians saw the collection which they regarded as comprising works by “not affirmed artists from faraway exotic places”24 as “works from authoritarian states that support official art.” It is true that the gallery was a political project from the beginning, and the acquired works25 were not always the most representative works of a particular artist. On the other hand, the collection’s potential to challenge the ways the Western art operates and produces hegemonic narratives/canons was not particularly well understood either. Unlike Western colonial museums of the past, the gallery in Titograd acquired “art of the world” solely in the form of gifts and donations, while attempting to develop its own cultural networks and frameworks of knowledge and to combine this with experiences from other parts of the non-aligned world.

These are only a few of the examples from Yugoslavia that were directly linked to the non-aligned cultural politics.26 It can nevertheless be concluded that while Yugoslav political manifestos of the time espoused the grand ideas of anti-colonialism, decolonialism and the struggle against cultural imperialism, the practice tended to be different. It took quite a while before art from the Third World (or “art of the world”) was discussed in terms of cultural and intellectual decolonisation, cosmopolitanism, internationalism, parallel (or local) histories, and other kinds of modernities in the sphere of art and culture.

Taking into consideration the wider context, the non-aligned transnational network did not produce a common tissue that would create a new international narrative in art. Western canons might have been challenged to some degree but with the exception of a few, sometimes extreme cases such as Zaire’s l’authenticité,27 the ‘non-Western’ cultural expressions were usually interpreted in the frame of ethnology or traditional arts and crafts.

What did happen though was the potential to think (“think with a difference”28) and create different histories (modernisms, arts, narratives etc.) that extended beyond the Eurocentric ones. There obviously existed a heterogeneous artistic production, a variety of cultural politics and extensive cultural networks which enriched the cultural landscape of the NAM and enabled discussions about the meaning of art outside the Western canon; this is something that this text also attempts to show.

The story of the non-aligned cross-cultural pollination is far from being resolved and concluded. That is why the task for us today is to discern what were the actual consequences of those progressive, even emancipatory, cultural politics on heritage and how they affected the development of new prototypes of art institutions, networks and epistemologies of knowledge. Have those ideas only been preserved as silent reminders of a possibility for a different cultural, artistic and museological perspective? Or were they perhaps seeds that would one day grow into trees and subsequently, into forests?