This article takes as its departure point Fragments, a series of rediscovered collages created by the Black British photographer Vanley Burke since the 1980s. It asserts that the materiality, process and theme of Fragments provides a clue to the emergence of strategic combinatorial aesthetics amongst the African Diaspora artists at the heart of the 1980s Black British Art Movement.

My concern is the connection between collage as a methodology and the suturing of fractured diasporic narratives that result from movement and migration. I am interested in the (dis)-connections between personal histories and received history; how neglected or hidden diaspora histories of resistance sparked by movement and migration can be mapped through a canvas, an installation or through pieced-together photographic images; how histories and identities can be worked and reworked by hand. I am interested in the way in which cultures collide, co-exist and coalesce—creating the creolised combinatorial aesthetic present in the works of such artists as Vanley Burke, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney.

Using a theoretical framework grounded in the writings of Kamau Brathwaite, Stuart Hall and Kobena Mercer, this article argues that the use of collage in this context might be seen as a strategic act of subversion and play that facilitates the mapping of histories of people on the move. Furthermore, this article advises that the above artists’ creolised combinatorial aesthetics parallels the development of “nation language”1 in the Caribbean—they are vernacular cultural expressions grounded in the re-assertion of agency through the piecing together of seemingly disparate fragments.

Vanley Burke Fragments

In January 2020 a visit to Vanley Burke’s apartment-cum-studio in Nechells, Birmingham, led to the unearthing of an intriguing portfolio of large-scale intricate collages entitled Fragments. These were created by the artist almost twenty years ago. The portfolio also contained close-up shots of selected sections of each collage. These collages were created in response to the artist’s own archive of documents, photographs and objects pertaining to the African-Caribbean presence in Britain from the mid-twentieth century to the present day as part of the Wolverhampton Art Gallery 2003 exhibition True Stories.

True Stories was a collaborative exhibition developed with contemporary artists Vanley Burke, Barbara Walker, Wanjiku Nyachae, Peter Grego and Bharti Parmar, working with two archives: the Vanley Burke Archive and the Benjamin Stone Photographic Archive. Other partners included Birmingham Central Library, the University of Central England, Black Country Touring, the Lighthouse Media centre and Arts Council England West Midlands. The exhibition was founded on the assertion that archives are always open to constant reinterpretation and reinvigoration. As curator Caroline Smallwood writes, in Fragments Burke devised a new way of reading his own archive: “By reconfiguring certain photographs in his archive and adding new images, he is montaging not only imagery, but stories, memories and personal histories.”2

Stone and Burke, though separated by a century, share a belief in the power of the photographic lens to capture layered histories for future generations to discover. They also share a passion for collecting contextual materials that breathe life into their photographs. Stone collected geological and botanical specimens alongside a record of personal life and creative practice. Burke collects ephemera, posters, records, videos, orders of services, ornaments, textiles, carvings and basketry. Stone and Burke also shared an understanding of the role of institutions such as libraries, archives and museums in preserving and providing access to their respective collections. In bringing their work together under one roof, the exhibition True Stories, sought to continue the artist/archivist’s work of representation, presentation and re-examination.

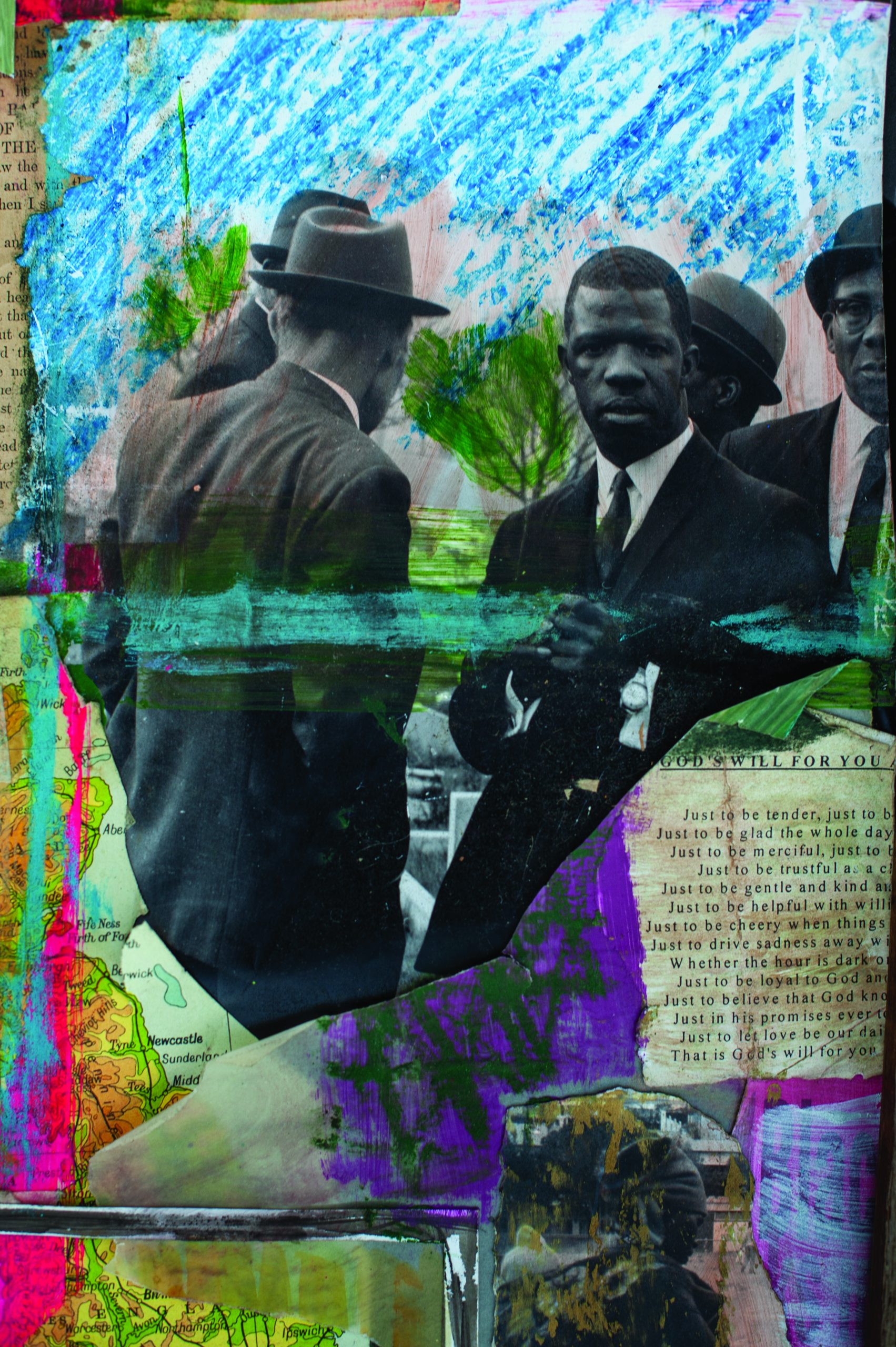

In respect of Fragments, Vanley notes that these pieces re-visit ideas from his childhood. He deploys a range of photographs from his collection and new images—for example, pages torn from magazines and newspapers—to cut and splice together multi-layered landscapes in which perspectives collapse—literally and figuratively. Images are cut, torn, digitally enhanced, pared down, recoloured, rearranged and pieced together. This process reflects Burke’s awareness of the tensions and conflicting viewpoints and power relations embedded within relationships, history and Caribbean spirituality. The constant doing and redoing, tearing and joining, sticking and unsticking reflects the cyclical nature of life: “creation, growth, entropy, death and re-birth.”3

Coming to Birmingham from Jamaica in 1965, Burke began taking pictures for an imaginary friend back home. This friend “needed to know what fog looked like, to see the faces of people whom I’d never met and whose names I heard every day back in Jamaica; he was my audience.”4 The images produced then were positive images of Black people in Britain. This made them unusual at the time. The collages reveal complex Black lives and complex Black experiences. By the time of True Stories, Blackness had come to mean something else; it was not the political construct that it was in the 1970s and 1980s (see below). The Black community re-presented in Fragments has a political and social identity that is not solely defined by the colour of their skin. Burke’s practice is that of a (hi)storyteller “capturing the moment before it passes.” The collage technique captures or fixes such moments in time, yet the urgency of the tearing, cutting, sticking, unsticking suggests a sense of motion that expresses what it is to inhabit the ‘in-between’ diasporic space. The dialogue has changed/is changing: “It is no longer linear—that is, between ‘Black’ and ‘White’—but more complicated, confused, confusing.”5 This is the multi-layered (hi)story being told by Burke through paper and glue.

Fragments #1, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Fragments #2, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Fragments #3, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Fragments #4, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Fragments #5, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Fragments #6, mixed media. ©Vanley Burke 2003

Collage, Diaspora and Aesthetics of Journeying

The constantly-on-the-move community that constitutes the global African Diasporas epitomises contemporary notions of diversity and syncretism. Our story begins with the rupture of the Transatlantic Slave Trade that took place between the 16th to the 19th centuries. It is a story that backdrops Burke’s and other artists’ mobilities. It would be true to say that African Diasporic peoples and cultures have journeyed via routes that were opened by trade and commerce. Central to diasporic experiences is the schism of migration (whether enforced or by choice), the notion of cultural exchange characteristic of creolised culture, and the concept of the past (albeit a fragmented one) acting as an incubator for and cutting into the present. The concepts of “travelling cultures” and “journeying aesthetics” attempt to capture the cultural expressions that emerge from these contradictions. However, cultural critic Kobena Mercer’s engagement with African diasporic art practices since the 1980s draws our attention to the issue of what he calls the “burden of representation,”6 whereby the work of Black artists is assumed to be issue-based, concerned primarily with identity politics at the expense of an appreciation of the materiality of the work itself. He notes that migration throws objects, identities and ideas into flux. Colonial encounters gave rise to a multiplicity of trajectories in which myriad cultural expressions were released from indigenous traditions and mobilised across networks of diasporic travelling cultures.7 Considering the materiality, process and thematic of key works like Burke’s Fragments, provides a clue to the emergence of strategic combinatorial aesthetics. Nevertheless, I do want to reference Stuart Hall’s assertion that “identity is a ‘production’, which is never complete, always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation,”8 to tie the ‘cut and mix’ nature of the combinatorial aesthetic to what it means to be in diaspora, that is, to inhabit more than one world and to experience the tension between the two.

In the essay Cultural Identity and Diaspora,9 Hall asserts that there are at least two ways of defining cultural identity. The first suggests that cultural identity is founded on shared collective identity, reflecting historical experiences and shared cultural codes. This creates a ‘oneness’ that binds, that sets aside all superficial differences. This, Hall states, is the bedrock of Caribbean-ness and by extension Blackness. This conception played a crucial role in post-colonial struggles at a global level and provided a creative impetus for emergent forms of self-representation by hitherto marginalised peoples. The discovery and re-examination of such shared cultural identities is often the object of research and creative (self)-making. Such practices rehabilitate us to ourselves and to each other. It is as though having a knowledge of the past as written by us, allows us to reconcile the effects of colonisation, such as a sense of “double consciousness.”10 Vital since, as Frantz Fanon writes:

Colonisation [was] not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it.11

This suggests that the production of cultural identity is enmeshed with the production or retelling of history, from the perspective of the formerly colonised, from the perspective of diasporic communities.

In contrast, the second way of defining cultural identity embraces difference. It recognises the “ruptures and discontinuities”12 that shape the uniqueness of the Caribbean. Here, cultural identity is seen as a “matter of becoming as well as of being.”13 Such cultural identities look forward towards the future whilst glancing backwards towards the past. Such cultural identities are constantly in flux, and are subject to the play of history, culture and power. Aligned to that, African Diaspora identities are always producing and reproducing themselves. They cannot be defined by purity or essence, instead they are defined by diversity, by difference, by creolisation. As previously stated, the Caribbean could be viewed as the home of syncretism. It is characterised by intermingling, blending, collision and coalescence, by ‘cut and mix’. This in turn gives rise to what Hall describes as “diaspora aesthetics,” born from post-coloniality. As Mercer writes:

Across a whole range of cultural forms there is a ‘syncretic’ dynamic which critically appropriates elements from the master-codes of the dominant culture and ‘creolises’ them, disarticulating given signs and re-articulating their symbolic meaning. The subversive force of this hybridising tendency is most apparent at the level of language itself where Creoles, patois and black English decentre, destabilise and carnivalise the linguistic domination of ‘English’ … through strategic inflections, re-accentuations and other performative moves in semantic, syntactic and lexical codes.14

Burke’s Fragments reflects this second definition of cultural identity. His expressive mark-making and over-printing re-articulate particular signs. The fragmented nature of his layered collages echo the “ruptures and discontinuities” that characterise Caribbean experiences.

I have previously drawn on the process of stitching as a metaphor for the suturing and retelling of fractured African Diaspora histories.15 Drawing on Sarat Maharaj’s notion of “thinking through textiles,”16 I posited the idea of stitching, and by extension working by hand, as both a means of thinking about oneself and one’s place in the world, and a means of thinking at a conceptual level beyond oneself. I suggested that stitching might be seen as an aesthetic, conceptual and subversive strategy akin to post-colonial life-writing and history-mapping.17 The need to ‘write’ in one’s own voice is central to these genres; post-colonial life-writing and history mapping give voice to the plural self, characteristic of an ‘in-between’ diaspora mode of being.18 The process of stitching, unstitching and re-stitching a crazy quilt,19 for example, captures a sense of multivocality that emerges from these ‘in-between’ diasporic identities in flux. Similar observations can be made when viewing Burke’s works with paper, glue and paint. The crafting and potential readings of each piece hinges on translation and re-inscription. But what do we mean by diasporic art, or indeed diasporic aesthetics? If such things exist, how might we characterise them? Mercer and Sieglinde Lemke are helpful on this issue.

Mercer and Lemke have noted that, despite the increasing critical discourse around diaspora studies, the characteristics and purpose of ‘diaspora aesthetics’ is under researched. Lemke rhetorically asks, “should the subject matter of [diasporic art] invariably reflect the traumatic events that precede a forced dispersal, or does it capture the nostalgic yearnings for lost origins? Moreover, is there a specific style that we can identify as ‘diasporic’?”20 Meanwhile Mercer, drawing on the work of leading Black British artists Keith Piper and Donald Rodney, identifies a collaged or combinatorial aesthetic that characterises both artistic practices and discourse; an aesthetic that is rooted in and routed through a relational understanding of identity that is distinct to African Diasporic experiences.21 He questions why the art world still fails to acknowledge the “creative energies of such cut-and-mix aesthetics.”22 Lemke suggests that diasporic art depicts either the moment of dispersal or the consequences of dispersal. Often a longing for real or imagined/mis-remembered homelands feature, as artists render a collective identity out of the bits-and-piecesness of fragmented experiences. Diasporic roots and routes are repeatedly rendered, since an appreciation of origins is key to our self-understanding. However, such backward glances, according to Hall, generate forward-looking art that cannot be represented from one perspective.23 The diasporic condition, by nature fragmented, gives rise to multiple-view perspectives. I agree to an extent, but I do not advocate any forms of African Diaspora essentialism. Hence the use of plurals—aesthetics, diasporas, cultures, practices—in this article as an attempt to signify nuance and difference. Furthermore, I am cautious of over-racialising the motivations and practices of African Diaspora artists such as Burke for this reason.

Method: Collaging the diasporic subject. The artist at work

But what of method? Mercer suggests that collage is a medium suited to the diasporic subject.24

Collage describes both the technique and the resulting work of art in which pieces of paper, photographs, fabric and other ephemera are arranged and stuck down onto a supporting surface.25

Torn paper. Cut card. Ripped cloth. Picked and unpicked fabric. Split wood. The cut-and-mix nature of collage echoes the improvisational multi-layered qualities and multiple-view perspectives of creolised Africa Diasporic cultures. The experimental use of collage in this context might be seen as a strategic act of subversion and play that facilitates the articulation of identities in constant flux and the mapping of histories of people on the move. The criss-crossing of the Atlantic by waves of migrants is artfully translated via the sticking, unsticking, repositioning and sticking once again that Burke adopts as the preferred method for the creation of Fragments. As stated earlier, the urgency of the tearing, cutting, sticking, unsticking suggests a sense of motion that expresses what it is to inhabit the ‘in-between’ diasporic space. His collaged approach also promotes layered interpretations as the eye travels back and forth to read the works. In contemplating textile crafts, I previously noted that the ‘diasporic view’ as a mode of creative making, critical thinking and looking feed on flux; it holds the tension between the multiple perspectives mobilised by migration; it thrives on “continual translation and re-inscription.”26 This is what we witness in Burke’s collaged works. As with the process of making textiles, the creation of a collage suggests “a way of thinking beyond fixed limits, one that resists the closure that occurs when we attempt to transcribe concepts through writing. The possibilities of multiple viewpoints and interpretations are reduced. Layers of potential meaning are emptied out.”27

Collage as Nation Language

Glued down. Stuck onto a new place. Maybe positioned by arbitrary forces and through the eyes of another with all their prejudices. Overlapping and with rough edges. Poorly defined borders with no history as guide. Out of position. The smaller part but still of the mother part, but now relating to its new, alone, independent position and now juxtaposed against other separated elements. Floating. An island adrift but perhaps freer to explore new possibilities? Creating a new history by necessity. Imposing a new language. These are my thoughts on collage as a nation language.

The creolised combinatorial aesthetic brought to bear by Burke on the history of the African Caribbean presence in Britain could be likened to a visual nation language. Both are vernacular cultural expressions grounded in the re-assertion of agency through the piecing together of seemingly disparate fragments. Brathwaite, writing about the ‘discovery’ of Jamaica, observes that the original Amerindian culture became fragmented with the arrival of European and African cultures—Ashanti, Yoruba and Congo—during the plantation slavery era. With that new creolised language structures emerged. However, these vernacular languages had to submerge themselves since the official language of public discourse was Standard English, the mother tongue of the planters, the language of the colonisers. Submergence performed an important interculturative purpose. The underground language of the enslaved and the language of the planters continually transformed themselves into new forms.28

Nation Language

Brathwaite asserts that nation language has its own rules and rhythms that are influenced by African models. Verbal nation language ignores the pentameter to better represent the voices that are shaped by a particular Caribbean environment and experience.29 Édouard Glissant expands on this idea, defining this language as a “forced poetics,”30 a kind of strategy since the enslaved were forced to use this language in order to disguise him/herself and to retain his/her culture. Closely rereading Burke’s collaged works, that in my view reference assemblage in African traditions, we find that the history of the African Caribbean presence in Britain is hidden in plain sight. Visual nation language might be seen as simultaneously revealing and disguising layered narratives to/from the viewer. Paralleling verbal nation language, the noisiness of Burke’s canvas creates multiple meanings. Sharp rhythmic variations are created by overlapping layers, rough edges and splashes of clashing colour. The sound explosions of verbal nation language are alive in the sudden pops of colour that Burke applies to his montage of images and texts. Stories, memories and personal histories are pieced together like the scraps of misshapen, cast-aside and forgotten fabrics repurposed to create a crazy quilt. There is a homemade vibrancy about these works that echoes the edginess of Ska, the “native sound at the yardway of the cultural revolution”31 that led to Jamaican independence. Crucial to Burke’s oeuvre is the emphasis on the African Caribbean community in Britain retelling its own collective cultural history itself, in its own words. This focus and methodology also calls to mind the riddimic dub poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson.32 This is about seizing agency, just as the detonations within verbal nation language mobilise a new consciousness of the self from the perspective of African Caribbean peoples and by extension the African Diasporas.

The Black British Art Movement

Burke’s collaged approach is, in my view, a reminder of the D.I.Y.33 aesthetics of the key protagonists of the 1980s Black British Art Movement such as Keith Piper, Eddie Chambers and Donald Rodney.34 These artists came to symbolise a new wave of young black-skinned practitioners whose work actively examined social and political issues, using methodologies and aesthetics that drew heavily on the features of the Pop Art era, using ‘readymades’, found imagery and new technologies such as photocopying. They shared a radical collective agenda, aimed at promoting political thinking amongst Black peoples in Britain by visually commenting on the social and cultural contexts at that time. They also sought to trouble the absence of Black artists’ work within the then mainstream white cube galleries and museums. Politically these were racially charged times. Creativity and conflict coexisted in the streets and on canvasses. A creolised combinatorial aesthetic can be seen on artworks, catalogues, posters and flyers for exhibitions. Keith Piper’s 13 Killed, a commentary on the New Cross fire on January 1981, exemplifies this cut-and-mix approach.

The fire that took place in New Cross, south-east London, UK, saw the massacre of thirteen innocent teenagers who had gathered at a house party to celebrate the birthday of soon-to-be-sixteen-year-old Yvonne Ruddock. Piper dismantled and reassembled newspaper reports about the event, cutting and splicing together images and text on a backdrop of charred wallpaper and skirting board that called to mind a domestic setting. In addition, Piper wrote messages to each of the victims, bringing human faces to the journalists’ reports, giving back a sense of dignity and personhood to the local Black community. It is as though, through the use of collage, this important pivotal moment in British history was retold from the perspectives of those whom colonial history and the contemporary racialised visual field had rendered invisible. This observation circles back to the focus of Burke’s work discussed earlier. The materiality, the process and the thematic of these works demonstrate the emergence of strategic combinatorial aesthetics.

In the designs for the Black Art Movement exhibition catalogues, posters and flyers, the then high-tech but now low-tech use of photocopied imagery, overlays of torn paper, alongside typeset and stencilled text mirrors Burke’s methodology. The monochromatic Black Art An’ Done exhibition poster, for example, consists of a photomontage of photocopied images of Piper’s work and those of fellow artists Eddie Chambers, Dominic Dawes and Ian Palmers. Similarly, the poster for Piper’s 1984 solo show Past Imperfect, Future Tense at the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, depicts a repurposed image of the infamous slave ship diagram positioned underneath the word ‘imperfect’. Four young Black boys carrying upturned dustbin lids as shields march across the centre of the poster; the word ‘tense’ is emblazoned across the chests of the two central figures. Carefully extracted from newspaper reports and reference books, the style, colour and texture of each component appears to mutate in relation to its new neighbouring element. Piper uses a stark tricolour palette of black, white and red to powerful effect. The stencilled words ‘imperfect’, ‘future’ and ‘tense’ stand out from a blood-red background. Piper’s and Burke’s cut-and-mix processes become metaphors for what is to be in diaspora—separate elements mobilise to create a new entity within an unfamiliar alien frame or context or culture, fixed in place, now in relation to the other, new and unrelated yet bound together.

Cut & Mix: Combinatorial Aesthetics and Agency Today

Riffing off Burke’s 2003 series of collages entitled Fragments, this article has examined the creolised combinatorial aesthetics of African Diaspora art practices since the 1980’s Black British Art Movement. Drawing on the writings of Mercer, Hall and Brathwaite, I suggested that collage was a strategic methodology and diasporic aesthetic device, tantamount to a visual nation language. Furthermore, I argued that its use in the context of African Diasporic art forms might be seen as a strategic act of subversion and play that facilitates the mapping of histories of people on the move and the re-assertion of agency. This cut-and-mix approach has continued. It has been adapted by a brand-new generation of contemporary Black British artists such as Richard Rawlins and Jade Montserrat using different materials and methods.

I conclude with a reading of Rawlins’ use of collage in the 2018 piece I Am Sugar. Where Piper and Rodney took up the use of photocopied imagery, Rawlins embraces digital technology to produce montaged works that comment on the entangled histories and traces of Empire and colonial thinking in everyday life. In I am Sugar we see a clenched black fist (a symbol of the Black Power Movement in America) emerging from the centre of a porcelain cup and saucer with a gilt handle. This particular series of works references Hall’s provocative statement in the 1991 essay, Old and New Ethnicities: “I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am the sweet tooth, the plantations that rotted generations of English children’s teeth.” Using just three simple elements—the fist, the cup, the saucer—Rawlins demonstrates the potential power of collage to continue to ‘speak’ about African Diaspora concerns, lives, experiences, histories and identities in the digital age.