INDIA: Leave the Tribe (1982)

We didn’t emigrate. We fled.

To ‘emigrate’ suggests a carefully crafted decision to leave one’s own country and to remain away. It takes all the force out of the propulsion that prompted our own hasty departure.

I was taught about push-pull factors in geography class when I was around ten years old. People migrate because they are driven out from impoverished, war-torn countries. Push factor. People migrate because they are drawn to the dream of a better life elsewhere. Pull factor. There are degrees of variation on the fleeing theme. Flee a country, a city, a neighbourhood, or a school. Get away from ruination, deprivation and misery. Fear can be a great motivator. This is a roving narrative of what prompted my family’s own departure and how I, as a child, grappled with leading an itinerant life.

My first birthday at Grihalaxmi Colony

in Ghatkopar, Mumbai (India),

14 July 1979. My dad is holding me.

My mother is from Chennai. All married women returned home to their families to give birth. As a result, I was also born in Chennai. I don’t remember the train journey I must have taken with my mother and brother to end up in Mumbai where my father was working as a young, ambitious banker in the State Bank of India. I have fleeting memories of childhood in Mumbai. They show up like haikus and float to the surface of my mind intermittently.

Learning English at Fatima Kindergarten; the Grihalaxmi colony1 where I played everyday with Israeli Jewish, Indian Muslim, Parsi, Gujarathi, Marathi and Tamil kids, speaking a mélange of Hindi and Tamil; the hijra2 who banged on our door in the middle of the night demanding money, whom my father had to kick and push out; bhel puri and paani puri3 stalls in the city; trains and the Arabian sea; falling in love with the voices of Mohammad Rafi, Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhosle on the local radio station or the devotional songs of M.S. Subbulakshmi.

We would have stayed in Mumbai. But we were pushed and pulled, in an emotional tug of war. Tribal wars with family became toxic and made life in Mumbai untenable.

I was four years old when we became expatriates. My father joined the Bank of Credit & Commerce International and we moved to Bahrain, a sovereign state in the Persian Gulf.

BAHRAIN: Bahrain, Burqas and Upset Bellies (1982-1985)

Migration made my stomach churn. I remember being ushered to the bathroom frequently with an upset stomach as a kindergartener. Being a foreigner and leaving friends behind was something I could not grasp cognitively.

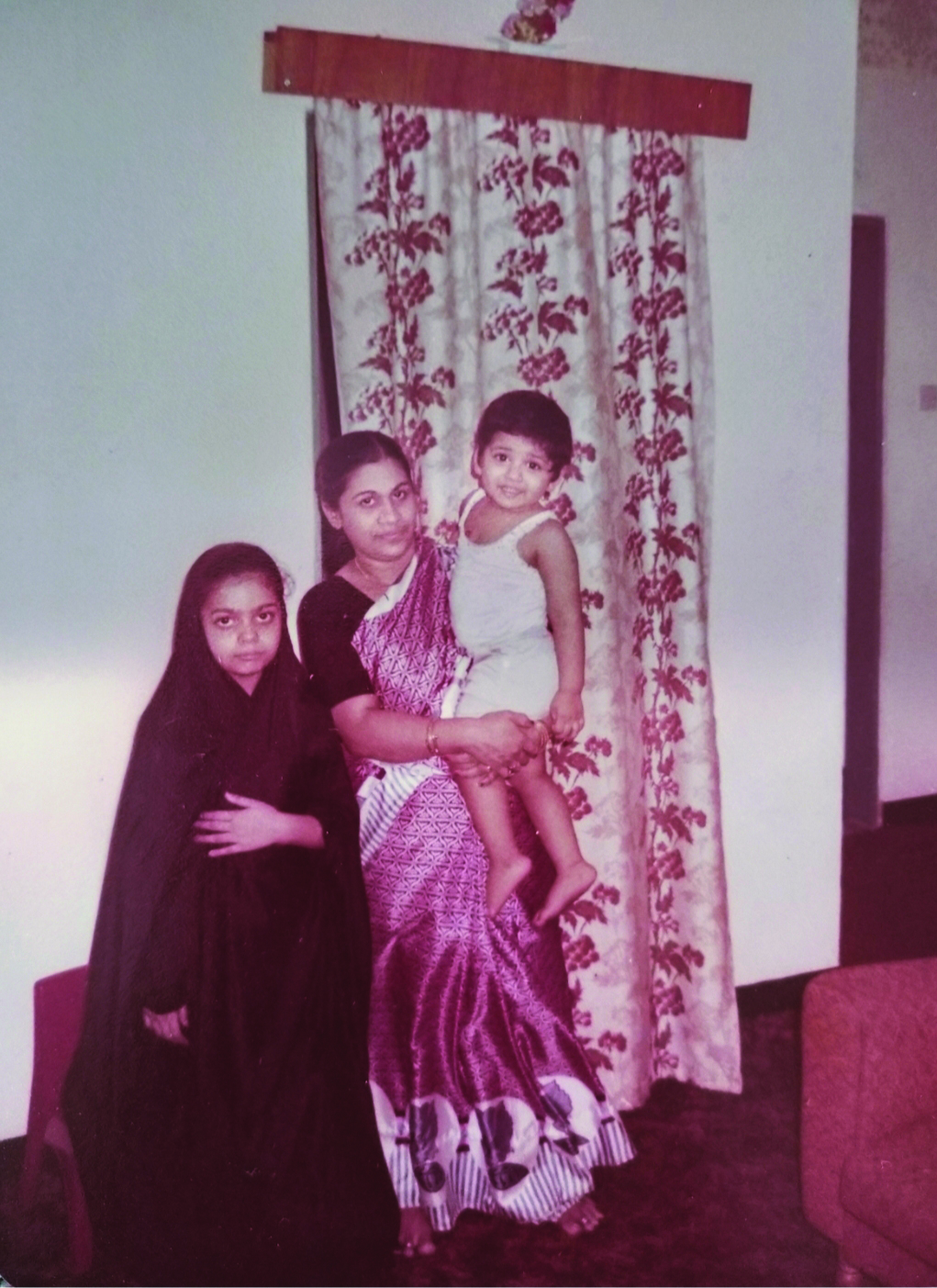

In Chennai with the cousins, 1984/1985. A decidedly Indian-style trip to the

beach. Get wet but stay clothed. I’m in yellow and terrified because I always

worried about family getting swept away by the currents.

In Bahrain, my idea of beauty, if I had one, shifted imperceptibly. Beauty became fragmented. Women were largely veiled in black burqas4. But I saw perfect wrists adorned in gold bangles; manicured nails painted red; eyes lined with kohl. I remember the law—if anyone tried to commit a robbery, his hands would be cut off (the criminal was always a man; the victim always a woman). That awed me as a six-year old. I thought, no wonder they can wear all that gold and be safe.

I also prayed.

Our neighbours were a lovely young Arab couple with a chubby, adorable toddler named Imdad. My mother regularly scooped Imdad up in her arms and crushed his cheek with kisses, while I borrowed his mother’s burqa to pray every evening. It became a daily ritual. I loved how I could smell her inside the burqa; how as a child, I could hide in the billowing fabric. How free I felt inside it.

Clad in our neighbour’s burqa, getting

ready to pray. My mum is carrying

Imdad. Bahrain, possibly 1984

UNITED KINGDOM: I’m a west Londoner (1985-1989)

We left Bahrain a few years later, just in time for me to start primary school in the United Kingdom. My brother ended up in a posh private boys’ school. I found myself in the nearest neighbourhood primary school in the borough of Middlesex, in Kingsbury, west London. It was a multicultural spot in London, peppered with Gujarati, and Tamil Brahmin immigrant families. My parents went to Harrods and Marks & Spencer on weekends, conducted elaborate pujas5 at home, and let us try fish fingers and chicken nuggets in social settings, so that we would not be ostracised for being vegetarian.

My school friends and I (centre), playing in our garden at Clifton Road in Harrow, on my 10th birthday, 1988.

At first glance, this also looks like a scene from Peter Weir’s 1975 film Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Walking home from school one day with a friend, our mothers trailing behind us, I was shoved off the pavement by a tall, skinny English girl with a wild mop of dirty, blond hair. She was probably sixteen years old, so in my seven-year old mind, she was a giant, far up in the pecking order. When I turned around, she looked at me and said, “Go home Paki.” She and her friend kept walking, laughing at us as they headed home. We waited until our mums caught up with us.

That was my first memory of racism. I was 7 years old.

I didn’t make much of it. Later that day, I thought about it again and framed the incident using this logic: she said go home Paki. She meant Pakistan. I am from India. Not Pakistan. She can’t tell the difference between Pakistanis and Indians, or the difference between these two countries. She is really stupid. The end.

Participating in the annual garba6

dance festival in Harrow, during the

Navaratri Festival, which honours the

divine feminine, 1987-1988. I’m in yellow

and green.

The naïveté that underpinned this argument was key to how I thrived in London as an immigrant among other immigrants. I could eat jacket potatoes and watch Guy Fawkes burn in a bonfire7; head to the countryside and celebrate Shakespeare; make massive collages of The Beatles in school and winter snowmen in our garden.

School concert at Uxendon Manor Primary School with a decidedly multicultural

student body, 1988. I’m in the red sweater with white elephant motifs.

I fought with and alongside other immigrant kids—fisticuffs, rivalries, best friend cliques.

But I could also be a decidedly uuru ponnu: a Tamil girl from the mother country who conformed to all of the cliches of my community—coconut-oiled hair in braids; pottu8 and paavadai9, sandalwood and spices, mangoes and tamarind in my daily diet.

In that way, I felt like a real Londoner.

Of course, at that precise moment, we left.

HONG KONG: Love & War (1989-1990)

In 1990 I had my first real crush. It was at South Island School in Hong Kong. He was a fourteen-year old English boy. I was twelve. The age difference was a big deal. Also, he was my best friend’s older brother. It felt forbidden. I stayed up nights thinking about how significant this was.

I did well in school and gave advice to troubled friends. I liked New Kids on the Block, Kylie Minogue, writing stories and playing sports.

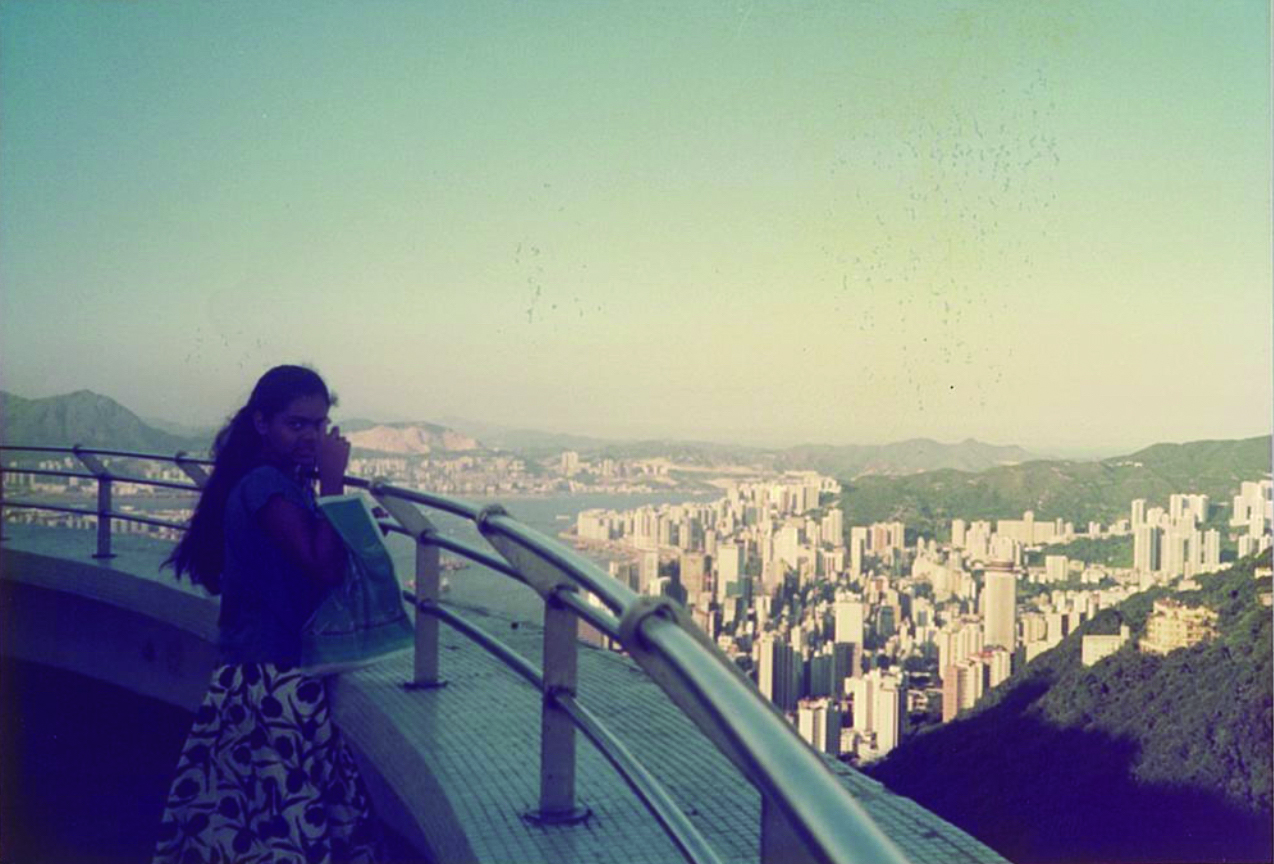

Feeling a little too ‘Indian’ in Hong Kong, 1990.

There was just one problem: I wanted to be white. It came as a surprise, this sudden need to flee from something so fixed, so inherent to who I was. Since I couldn’t stop being brown, I focused on being thin instead. The plumpness that Asians traditionally associated with prosperity and good health, was socially unacceptable amongst pre-teens in an international school.

India hadn’t left my life, even if I’d left India. As expatriates moving from one country to another every few years, we returned home in the summers to visit relatives in Chennai and Mumbai. I swung like a pendulum—brown girl trying to be white in an international school, foreign girl trying to be a Tamil Indian girl again during the summers. Bicultural, fragmented, constantly in motion.

It took skill and a lot of energy. So I wasn’t prepared for the two other things that happened in 1990. First the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) began losing staff by the droves. Regulators speculated that massive fraud on an unprecedented scale was taking place. Then, Iraq (under Saddam Hussein) invaded Kuwait.

On television, they kept showing footage of huge barrels of oil burning. The First Gulf War (Operation Desert Shield) had begun.

The Indian parents around me murmured worriedly. My father looked genuinely anxious for the first time. The BCCI was a powerful institution and it went on to crumble spectacularly. Depending on who you ask, the BCCI collapse was engineered by the United States government to shut down a Pakistani bank that had become too powerful and was a threat to UK and US interests.

A U.S. Navy Grumman F-14A Tomcat

from Fighter Squadron 114 (VF-114)

Aardvarks flies over an oil well set

ablaze by Iraqi troops during the 1991

Gulf War. Photo: Lt. Steve Gozzo, USN.

US Defense Imagery. Public Domain.

I didn’t particularly care about banks and at the age of twelve; I wasn’t an anti-war activist either. But the Iraq invasion was the first real memory I have of war. I understood that something terrible was happening. It forced us to migrate, again. This was my fourth move in 12 years. I was used to leaving and saying goodbye; to morphing, pretending and adapting. But this move felt different. It was sudden, unexplained and, for the first time, I had the sense that I wasn’t going to be with my family.

Ootacamund, India: Ghosts, Maharajahs & Lice

(August to December 1990)

A job opportunity took my father to Singapore. Concerned that the school-term in the city-state started in January each year and that I would be there in the late summer of 1990 with nothing to do, my parents deposited me in a boarding school in Ooty, a hill station in Tamil Nadu, India. They took my brother with them to Singapore.

Blue Mountains School today.

Courtesy Blue Mountains

School Management.

The grounds and the cottage that housed Blue Mountains School was built by Frederick Price, formerly the Governor of Burma. The house was sold to Vidyavathi Devi, the Maharani of Vizianagaram, before India gained independence and Price went back to England, since the English weren’t needed anymore.

Ooty wasn’t the town’s real name. It was Udhagamandalam. The British looked at other provincial references and came up with Ootacamund. Even that was too hard for their English tongues, so they shortened it to Ooty.

It had been a hill station getaway for British colonial administrators before independence. It was to southern India what Kent and the Lake District was to England. If you couldn’t send your child to a boarding school in Kent, you could send them to Ooty.

When I went there, the school was a ramshackle place with intermittent running water, no heat, bedbugs in the dorm room beds and a lice infestation among the student body.

Each weekend, the cleaners at the school lined us up and parted our thick black hair to weed the critters out. I liked the faint but sure click of lice being killed. I’d sit there, eye-level with her waist (who was she? A nameless Tamil woman), while she worked methodically to kill the adults and weed out the eggs. These women felt like mothers.

Afterwards we washed our hair and played on the grounds. Our scalps felt icy in the misty climate. Most of the kids had adoptive parents, were orphans, or were from wealthy, dysfunctional families. Like me, several had been sent to the school at the last minute. A lot of them had parents with jobs in the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait or Doha.

One of the students was a soft-spoken androgynous Parsee girl who sleepwalked every night. She hurt herself a few times—scratches and cuts. I don’t think we ever woke her up during these nighttime jaunts.

I became painfully aware through incidents like this that we needed our families. We felt like non-monetary deposits in bank vaults: valuable and protected but unloved and isolated. In the middle of a financial crisis, a divorce, or career failures, we would have preferred being with our parents to being alone. So when the December winter break came, I packed my trunk and headed for Singapore.

My parents were new immigrants there. So long as nothing catastrophic happened again, the plan was to stay. They had enough to start somewhere in the middle. Middle-income, middle class and middling.

SINGAPORE: Too cheem10or not too cheem (1991)

There I was on the grounds of Thomson Secondary School11 in 1991, a 12-and-a-half year old Indian immigrant raising the Singapore flag and saying the pledge. No one told me whether or not I was supposed to participate in these rituals reserved for citizens. So I learned to sing an anthem in a language that I didn’t understand and to pledge allegiance to a country I hardly knew.

In that first year, my hand was on my heart, but it frequently turned into a fist. I mimed the words and never meant it. Sometimes I said it in a monotone. I never looked up. The flag fluttered, wistfully.

After school, waiting at the bus stop to head home, I heard Indian students speaking in Tamil. “She thinks she’s better than us. Yah, ignore her. She’s not one of us.”

They had no clue that I understood every word. I never reacted. I just hated them and said mentally, “Yes, I am better than you. Better-looking, better educated, better, better, better.”

Mrs. Khoo, the principal of the school, was a visionary woman. She had to deal with after-school gang fights and the school wasn’t going to produce government scholars who would be featured in The Straits Times, so she liked me. She told me that her school would be a little less like the international school I had attended in Hong Kong, adding however, that I would be given “many opportunities” to thrive.

I soon realised that this made me target number one for social exclusion. If I’d been a boy, I’d have been beaten up. I was a girl, so everyone ostracised me.

Kylie Minogue and NKOTB got ousted. The metal years had begun and for the first time in my life, music took on metaphysical significance. On my backpack, I scrawled the names of heavy metal bands: Metallica, Guns N’ Roses and Anthrax. I made fake tattoos with a black pen on my wrist.

I made posters of album covers with art paper and paints to put up on my wall. My brother wrote out all the lyrics to the saddest heavy metal songs.

Our parents reluctantly relented and gave us pocket money for these things, a little afraid of the depressive beasts their children were turning into. We made sure they knew it was entirely their fault. Songs like Something I can Never Have, Terrible Lie (by Nine Inch Nails), and The Unforgiven (by Metallica) formed the basis of our world-view. When I wasn’t in school, I wore baggy black clothes and wrote pensive poetry. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor wailed, “I was up above it, now I’m down in it.” He was talking about us.

While the Indian kids ignored me, the Chinese kids at the school asked me, “You’re Eurasian, aren’t you?” I wondered if I should be flattered that they thought I was partly white, or European in some way. I’d always wanted this, after all. I had finally achieved the kind of racial ambiguity and mobility in terms of my identity that I’d always desired. I was non-committal in response.

Immigrants were rare in 1991 and most of them didn’t end up in neighbourhood secondary schools. In Singapore, your identity was conferred upon you regardless of the complexities of your family history. You were: a) Chinese, b) Malay, c) Indian d) Others.12 “Others” seemed to be a catch-all category for various racial groups, Tincluding Eurasians.13 I didn’t fit the racial stereotype of Indians that seemed prevalent in Singapore and when the students in the school figured out I wasn’t Eurasian, they didn’t know where to put me.

Boys used to like me until I migrated to Singapore. At school, boys thought it was weird that I ran so fast during P.E. class14 or tried to answer questions during English and Literature class. After I’d say something, they’d say, “wahhh, so cheem.”15 I had no idea what it meant.

But saying less in a classroom in Singapore had always been a survival tactic. A way to not let on if you were clueless. It’s not like they were timid. I saw them during recess in raucous groups, speaking in Hokkien, Malay and Tamil.

I kept being cheem in class, and morose during recess. It wasn’t the best move. All the boys from options a), b), c) and d) generally liked girls from options a), b), c) or d) respectively. The popular girls around me seemed exaggeratedly feminine and affected a delicate disposition, which made the boys like them more. I hated being a girl. I ditched the dresses and feminine affectations. I desired gender ambiguity but I could never quite pull it off. I kept trying to move into a body that would better help me communicate the sense of exclusion I felt as an immigrant teen in Singapore.

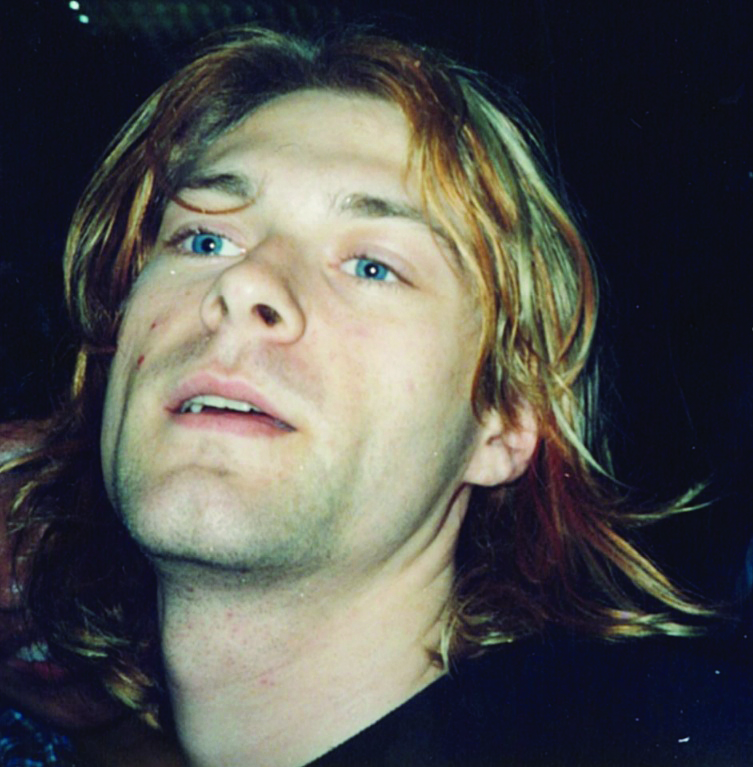

Then a Seattle rock band called Nirvana released their album Nevermind in 1991 and everything changed. Music journalists said the band was single-handedly going to start a music revolution—the mainstream would go alternative.16 In 1992, Dave Markey’s documentary The Year Punk Broke was released. It chronicled Sonic Youth’s 1991 European summer tour with other influential grunge and punk bands of that period like The Ramones, Dinosaur Jr., Nirvana, Babes in Toyland, and Mudhoney. The film affirmed that punk had, indeed, broken. We all felt it.

I took down the posters I’d painted of the Guns N’ Roses’ Use Your Illusion I & II album covers (blue and red). Metallica’s Black album got shelved. The metal bands made me want to be more of a boy. To rebel was to be tough, masculine. Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain made me want to be a strong girl. Through his music I discovered all-female punk bands like Bikini Kill, The Raincoats, and Shonen Knife.

At around the same time, I met a brooding, melancholic girl called Shulian. She’d read everything ever written by Thomas Hardy and the Brontë sisters. She felt like a walking English weather system—around her, things felt cold, dreary and wet. Like me, she seemed a little lonely.

She was Singaporean and Chinese, but seemed thoroughly out of place. I realised there were Singaporeans who didn’t conform to racial stereotypes or limiting categorisations of identity. So we were weird together. We could be cheem and ignore anyone who tried to make fun of us. Fewer and fewer people did.

Once, during English class, I said “Jesus” exasperatedly. The teacher, Mr. Ghazali, looked at me and said, “Don’t use the lord’s name in vain.” He had a glint in his eye. I had just sworn. I felt cheem and ballsy. The others in the classroom were vaguely impressed. Somewhere along the way, the ah bengs, ah lians17, the quiet English literature genius and the Indian immigrant metalhead all got along. “Friends” was probably too strong a word to describe it. But I didn’t feel invisible anymore.

Meanwhile, my brother and I saved our pocket money to buy more album cassette tapes. We took the bus to Changi Airport to see Nirvana fleetingly when they came for a stop-over visit before heading to Australia for a gig in 1992. It was a profound pilgrimage. We didn’t know it at the time, but Kurt Cobain was high on marijuana. Possession and consumption carried the death penalty and he escaped it. It made the whole experience even more radical.

High and mighty. Kurt Cobain

being accosted by fans at Changi

Airport in 1992. Photo: Vijay Ramani

On 29th September 1992, Rollins Band, fronted by acerbic punk rocker Henry Rollins, played a show at the Singapore Labour Foundation. The music seemed to rend us. At the show, hardcore kids, skinheads and punks slam-danced and bodysurfed. An article in The New Paper portrayed it as acts of violence.18 In the mosh pit, I saw wiry bare-bodied guys ensuring that no one broke their skulls or necks; body surfing was a dance and it took skill to do it without hurting people.

Soon after that, the government banned slam-dancing. We raged and continued going to local gigs. I never felt more at home in Singapore than I did in these moments. I felt momentarily free of categorisations when I immersed myself in live music. I was glad I wasn’t invisible anymore. But I wanted to be seen and heard.

I left the school I’d fought hard for two years to find a foothold in because I believed I could find a better environment to thrive in as a teenager. I left my friend. I felt guilty but I sensed something pulling me away from the cultural periphery. I was tired of always being the foreigner and the outsider. I didn’t mind peripheries as a whole. I just didn’t want to be excluded from everything altogether.

Girls & Gigs (1993-1996)

In 1993 I was fifteen and transferred to my eighth school – the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ Toa Payoh). Now our mornings began with reciting the Hail Mary prayer and the pledge. I was praying to a god I didn’t believe in and pledging allegiance to a country I wasn’t actually a citizen of. I could do this now, without feeling anything one way or another. I’d learned to compartmentalise. I’d begun to culturally integrate.

At CHIJ, there were a lot more Eurasian girls. They were cultural hybrids, so it didn’t faze them that they couldn’t pin me down. I had become accustomed to the ‘Straight Singaporean Chinese’ boy or the ‘Straight Singaporean Indian’ girl (and variations on that theme). I’d been told this was the norm. Here, I encountered a lot of ‘miscellaneous’ girls – lesbians, butches, rockers, nerds and artists. There seemed to be room for everyone; everything spilled over, nothing fits in place.

CHIJ Toa Payoh Prayer Room, 1994 (date on photo is incorrect).

Many a free period was spent in this room, discussing spirituality and chanting Sanskrit mantras.

At morning assembly, the classes were always lined up in rows like military platoons. In the line next to mine, I met a girl who played in a band. She got a whiff of my music tastes and started surreptitiously passing me demo tapes by local bands. Music had always felt a little forbidden. Now it felt like contraband.

I became close friends with an eclectic Eurasian girl called Kaurina. Everything about her fascinated me—most of all, her ability to hold an array of contradictory ideas in her mind. We would sit in the prayer room talking about bhakti movements in India, and what kind of meditation made us feel grounded. I returned to my roots in a roundabout way: as a hippie. An acoustic guitar-playing, mantra-chanting, chilled out teenager who read Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. The irony was never lost on me.

Strict Catholic girls would castigate us for talking about pantheistic gods in the prayer room. They warned us of the fate awaiting our souls if we kept at it. We smiled and thanked them for caring. I was reminded again of boundaries. But differences were necessary. I started seeing that. You were less liable to take your worldview for granted. The tension could be useful, if it didn’t descend into prejudice.

The hippie years, 1994. On the walls: Krishna, Kandinsky,

Suzanne Vega and Kristin Hersh

My brother and I started going for gigs at The Substation and World Trade Centre. I discovered how diverse and rich the local music scene was by listening to bands like Psycho Sonique, Fuzzbox, The Pagans, Concave Scream, Opposition Party, Stompin’ Ground, The Oddfellows, Still, Rocket Scientist, Sideshow Judy, etc. To make sense of the scene, I began reading a local independent rock magazine called BigO (Before I Get Old). Founded by brothers Michael and Philip Cheah, together with Stephen Tan, it was in print from 1985 to the mid-2003s and was also where many writers cut their teeth as local music and film journalists in Singapore.

Fugazi at Bukit Batok Community Club, 8 November 1993.

Photo: Fugazi

In June 1993, American post-hardcore band Fugazi released their third album, In on the Kill Taker. Once again, I felt my worldview shift as I carefully read the lyrics to their songs. In Facet Squared, Ian MacKaye sang:

It’s not worth, it’s the investment

That keeps us tied up in all these strings.

We draw lines and stand behind them,

That’s why flags are such ugly things

That they should never touch the ground.

Flags were difficult for me. As an immigrant who had no real prospect of returning ‘home’ to India, I didn’t understand patriotism or pledges. It took me a long time to really understand the verse from that song and to let the revelation sink in: nation states and politics drew boundaries that were artificial. While sovereignty mattered, the ground itself was sacred and could not be marked or divided. Flags desecrated the earth. Through hardcore music I also learned about community as something we could create.

And communities showed up spontaneously, in the most unexpected places.

Posters for the two gigs that Fugazi performed in Singapore

(8 November 1993. and 8 November 1996).

©Nasir Keshvani and ©Steven Tan

Fugazi came for their first show in Singapore in November 1993 and insisted on playing in an affordable venue. Prohibitive rental costs meant that audiences ended up paying for it with over-priced tickets. So there we were, gathering excitedly in the main sports hall of Bukit Batok Community Club to watch a post-hardcore band from Washington D.C. play its first show in Singapore. The gig cost us $15 and proceeds from the show went to the Bukit Batok Constituency Welfare Fund.

They were also in Singapore in the wake of the slam-dancing ban.19 That meant the community club (CC) had to put down a $2000 deposit. If anyone slam danced, the CC would lose the deposit. An angry German fan protested and was put in his place by MacKaye, who made sure the deposit would not be lost because of one irate fan. Everything about that show felt revolutionary. Unlike the Rollins gig, anger wasn’t the thing uniting the crowd.

In January 1994, Kristin Hersh, lead singer of alternative rock band Throwing Muses, released a solo album called Hips and Makers. She was featured in BigO magazine. Intrigued, I immediately purchased the album. Her weird chord structures and disjointed lyrics upended my world again. I stumbled through writing lyrics and taught myself how to play the guitar, dreaming of the day I’d record my own songs and play gigs.

In 1995 my brother got a summer job and used his savings to help me record, master and duplicate my first demo tape. I recorded another demo a year or so later, sold them at Roxy Records in Funan Centre for $5 a tape, and began playing gigs at The Substation, Velvet Underground, at polytechnics, and any venue that opened a space for local musicians to perform.

Playing one of my first gigs as Self-Portrait with Kaurina and Noor Hairi (now the lead singer of local band The Guilt),

The Substation, 1995. Photo: Vijay Ramani

Music and writing became a way to make sense of movement, disjuncture and disorientation.

In 1997, I got a scholarship to do my undergraduate degree in Canada and packed my bags for yet another country. For the first time in my life, I left of my own violition. It finally felt like I’d reclaimed movement. I wasn’t being dragged along and I wasn’t fleeing. I was going somewhere.

With bandmates Pankaj and Damon in Peterborough, Ontario (1997).

We briefly gigged across Ontario as Lost in Delhi.

Photo: Mime Radio

Quitter / Stayer / Emigrant / Immigrant

I’m heading for the trees over there.

If that’s not a destination, I don’t care.

– Buzz, Throwing Muses from the album Limbo, 1996.

Was I an emigrant or an immigrant? “To emigrate is to leave a country, especially one’s own, intending to remain away. To immigrate is to enter a country, intending to remain there.”20 I suppose we were emigrants who became accidental immigrants.

This is why I found former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong’s reference to “quitters” and “stayers” in his 2002 National Day Rally speech problematic.21 The basis of the speech was to criticise Singaporeans who left the country when circumstances became too challenging to remain. That sentiment continues to resurface whenever nationalistic rhetoric is invoked in times of crisis. And now, at a time of a global pandemic, we want the foreigners to quit, and the Singaporeans to resolutely stay.

But leaving is not always about quitting, or lacking tenacity. What awaits you elsewhere will require stamina. Even when you’ve fled, it aches inside. It’s bittersweet. You feel split and then you glue all the parts back together to feel whole again. Memory muddles things. You remember it being worse than it was. You remember it being better than it was. To stay doesn’t always require tenacity and persistence. Sometimes, gravity takes care of it. You stay and stop struggling.

I’ve always wrestled with language. What little I know seems woefully inadequate to explain the conditions that characterise this movement: departing, arriving, fleeing, settling, staying, temporary, permanent, escaping, returning. What do these words mean? Each speaks to a particular moment in time, but not to the experience of migrating and moving as a whole. And as the child of immigrants, my experiences were littered with disjointed stories, of past lives left behind, reinventions and reiterations with certain details excised.

Poet and classicist Anne Carson describes writing as a “struggle to drag a thought over from the mush of unconscious into some kind of grammar, syntax, human sense; every attempt means starting over with language.”22

Migration (of any kind) feels exactly like this. You must drag over the mush of your cultural codes and memories into another way of life, another space. You try to make sense of others. You try to make sense to others.

You’re always starting over.