“Today, we remain stuck in the present. The loss of a reliable historical perspective generates the contemporary feeling of living through unproductive, wasted time.” — 191′]Boris Groys1

Mobility

Today as I write this, a global pandemic is unfolding. Mostly the pandemic is taking place for me online via information from all over the world. We know that virus is mobile and we, humans, its mule. That is a very straightforward idea of mobility. Hop a ride and travel round the world. There is also the other thought, the internet provides speedy access to knowledge and information, that is seeing without moving. But what can mobility mean to an artist? In a prosaic way as I have suggested: travelling, seeing, showing.

In today’s sense the idea (and possibly ideal) of mobility often serves artists engaged with notions of identity and politics. Francis Alys, the Belgian artist based in Mexico City, for instance, is a good exemplar of this particular mode of interrogation. Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing), 1987, was an action in which Alys pushed a block of ice around Mexico City, or The Green Line, 2004, in which he walked along part of the green line that demarcated the different powers that administered Jerusalem, dripping green paint along the way. It is a remake of his 1995 work, The Leak, in which he took a walk from his gallery in Sao Paolo, dripping paint, and leaving a trail of blue splatters as homage to Jackson Pollock. His work is clever, and in his actions, there is a poetry as well as a pointed politics. Changing or charging the Abstract Expressionist gesture into a political one. Or, in the case of the block of ice, an existential statement about labour. Alys’ works use motion but require the viewers to have a measure of global understanding or awareness.

From the point of our discussion, Alys’ is a very straight forward display of movement, motion, international travel, understanding, and thus mobility. However, I’m interested in another way to look at that notion. The one performed in painting through its materiality and history. Wander through any art gallery, and you find painted objects that belong to different eras, or even contemporary ones. Their singular reified nature may convey a sense of being “stuck” in their moment, yet, illogically even, they still speak to us in our present.

Can looking at a singular static object make us travel? What I want to explore is the notion that paintings tend to be far richer objects than they first appear. To demonstrate this, let us take journey through two paintings and an exhibition that may or may not be tangentially connected, outside of the fact that they are paintings. And just maybe that is enough. Before returning to Groy’s notion of wasting time in the present. For the moment, let’s call this trip (no pun) a travel through time, or maybe with time…

Wandering

Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe, 1863

Edouard Manet, Lunch on the grass (Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe), 1863

Oil on canvas, 208 x 265 cms

Collection of Paris, Musée d’Orsay, donation by Etienne Moreau-Nélaton in 1906

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay)/ Benoît Touchard / Mathieu Rabeau

It is well known that the composition of Edouard Manet’s 1863 masterwork Le Déjeneur sur L’herbe draws from Raphael and Giorgione or Titian. The painting depicts two dressed men picnicking alongside a naked woman in the countryside, in the background a semi-dressed lady bathes in a pond. At their side sits a basket and food. To be precise, the composition actually draws from Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after Raphael’s The Judgement of Paris, 1510-20, and the young Titian’s, then thought to be the hand of his master Giorgione’s, Concert Champetre, 1509, which is located in the Louvre. The former provides the poses for the foreground trio, while the latter depicts clothed males with undressed females. In both cases it is the portrayal of a bacchanalian reverie in a rural setting. However, the modernist art historian Michael Fried, from which this analysis draws, also connected Manet’s early paintings with French and Flemish sources, touching on all the major European schools of painting and ending with a particular mode of French painting.2

Fried points out that Le Déjeneur is in the spirit of Antoine Watteau’s fête galante (courtship party). This category was created by the French academy to accommodate Watteau’s variations on the fête champêtre. That is the garden party or country feast populated by elegant guests, occasionally in fancy dress, which were popular in the 18th century French courts. This connection with Watteau’s fête was also noted by the critics of Manet’s era. In addition, Fried deduced that Watteau’s La Villageoise, which depicts a woman wading into shallow water with skirt upraised while glancing to the side, provided the pose for the bather in Le Déjeneur. In fact, when Manet’s painting was first exhibited in the Salon des Refusés in 1863, it was titled Le Bain (The Bath), and thus placing emphasis on the action in the background. A final connection is to Gustave Courbet’s, Young Women on the Banks of the Seine, 1856-57, having caused a scandal in the Salon of 1857 with its depiction of two women of loose morals—as was commonly accepted then, like those of Le Déjeneur. Fried points to the boat in the background as Manet’s “gratuitous quotation of Courbet’s rowboat,” which then connects the two paintings in his [Fried’s] eyes.3

Why even consider seemingly less direct quotations by French painters when the Italians provided such obvious points of reference? In “Manet’s Sources,” Fried argues that the idea of Manet we know is seen through the prism of Impressionism, that is, through the vision of the artists that came after, who were in fact inspired by the Frenchman. It is akin to our thinking of Cezanne through Picasso’s cubism. The point of connecting with Louis Le Nain (in Manet’s previous work, Old Musician, 1862) and Courbet is, for Fried, a sign of Manet’s commitment to their ideals of realism. This fact evades us given our Impressionist-coded outlook. Fried outlines a different zeitgeist: what he terms the “Generation of 1863,” comprising of Henri Fantin-Latour, James McNeill Whistler, and Alphonse Legros, as well as Manet.4 And in this, grasping the “pre-Impressionist meaning”5 of Manet’s paintings through his peers, instead of the ideas around gesture, roughness and spontaneity, qualities that are ever present in Manet’s painting. However, it is the notion of allusion and absorption of his subjects and compositions that Fried is interested in teasing out. In one sense it is a question of nationalism, identity and painting. “Which painters, ancient and modern,” writes Fried in 1967, “are authentically French and which are not? More generally, in what does the essence or natural genius of French painting consist? Does a body of painting in fact exist in which that essence or genius is completely realised? Has painting in France ever been truly national, or has it always fallen short of that ideal, however the ideal itself is understood?”6 These were the questions and thoughts posed by critics, historians and artists of the time. Fried, in Manet’s Sources, is interested in first a notion of Frenchness that critics at the time were espousing, and then of a universality. In this last point, I would add that in our terms today, we could say Manet brought a sense of “contemporaneity” (“modernity” would have been the phrase he would have used in his time) to his painting; he was very contemporary in his concerns to engage with the French painting of his era (such as Le Nain, Courbet).

Rather than rehearse the intellectual complexity posed by Fried’s analysis in terms of absorption,7 or even the visual complexity and ambition (and ensuring scandal) within Manet’s painting itself (comprising of all the genres: history, still life, portraiture, the nude, etc),8 it is the idea that this painting is not a sealed universe (of a picnic scene) in itself and belonging to the past.9 In rehearsing the complex matrix of sources to Le Déjeneur, as pointed out by Fried, I hope that not only a celestial sense of connectivity but also a feeling of time flowing through a singular object comes to the fore. What do I mean by this? Well, when we confront Manet’s masterpiece in the Musee D’Orsay we see it in the present. But within the painting, there lie references to 16th century Italian art, as well as an ambitious attempt at contemporary painting in 19th century France by way of past century of French masters.

Connections: Brice Marden, Boston, 1991

Another artist that connected with Manet, albeit more tangentially, is Brice Marden. It may seem strange to bring together an American renowned for his reductive monochromes with a French artwork rich with figurative allusions and pictorial complexity, but in 1991 Marden organised an exhibition at Boston’s Museum of Fine Art that included the Frenchman. This was part of their Connections series where artists were invited to intersperse their work with selections from the Museum’s collections. Boston is also the city where Marden studied as an undergraduate. In his introduction, Marden’s co-curator from the museum, Trevor Fairbrother, deduced that a “taste for the painterly and for the somber was probably reinforced by two large works by Edouard Manet that Marden studied in this museum during his student years in Boston.”10 The resulting show was akin to a mini-survey punctuated with paintings by Ensor and Gauguin among others as well as prints and drawings, etc., as well as objects from Marden’s personal collection such as Neolithic Chinese Jars and 20th century scrolls and textiles. In his review The New York Times critic, Michael Kimmelman compared the small black Marden situated near Manet’s The Execution of the Emperor Maximillian. He writes: “The lush surface of [Marden’s] Earth I echoes the rich blacks and grays that are to be found in the Manet. But the relationship between these works is more than formal. Mr. Marden suggests that the tragedy explicit in The Execution is somehow implicit in his abstractions. Works in the same gallery by Goya, Giacometti and Zurbaran similarly underscore the idea. And at the same time, they emphasise the figurative implications that Mr. Marden seems to hope a viewer will see in his spare designs.”11

Over the years, Zurbaran and Goya were also cited as inspirations, but a key influence not included in Connections: Brice Marden was Jasper Johns. His encaustic paintings in the 1960s depicted flat things in the world, such as flags, maps and targets. These representations could be perceived as self-referential: the painting of the flag is itself a flag, and a target is a target. For Marden they were also “maintaining the plane… [it is] this almost mythological illusion/non-illusion on the surface of the painting.”12 Marden’s response was to drain the imagery away and use wax to create large monochromatic ‘things’. These early works were made with a combination of wax, turpentine and oil paint applied with a palette knife. I say ‘things’ of his earliest works as they were painted from the top and edge to edge, while at the bottom the paint was allowed to drip. These dribbles act in reinforcing each painting’s physicality, while ‘being’ traces of their hand-made nature. In addition, their smooth wax surfaces imbue the rectangular canvases with a sensuous object-like quality. Illusion dissipates right there on the surface, as if it had been pushed down and melted away. Marden refers to these bottom edges as “open”: working on the ‘plane’ so to speak.

“Open” is perhaps the operative term in relation to his oeuvre and approach, despite their early resemblance to minimal art—the movement of his generation. An early Marden’s reductive materiality is only really an anchor for its evocative qualities. It is through colour as Fairbrother and Kimmelman accurately noted, where his art opens out to the world. In the case of Earth I, its blackness draws in the emotive drama of Manet. Likewise, it is colour that brings up ‘subject matter’ for many paintings of that period; it is usually a sense or feel for landscape or nature. However, it is the spatial quality we find in our landscapes rather than a specific place—instead of a depiction, it is a feeling. For instance, the monochromatic Nebraska, 1966, is a “homage”: its colour, green-grey, found while driving through the US state: “viridian, plus this, plus that, plus that.”13 While the Grove Group series takes its palette from olives trees in Greece, Marden had said: “I don’t try to replicate nature. I just try to work from the information that nature gives me.”14 And this information is colour.

Marden’s paintings of that period, Earth I, Nebraska, at first inferred an end to painting, as if they were the last paintings in a Modernist end game. Yet, we know now that they are not the last, instead they recall other monochromes, reductive painters and endgames: Reinhardt, Malevich, Newman, Yves Klein, Rauschenberg (whose monochromes, despite their jest-ful gestures, were nonetheless single coloured), Richter, even Stephen Prina. On the other hand, their wax surface conjoins with artists like Johns and Beuys. Instead of time moving backwards that Le Déjeneur performs, there is a moving sideways as well as circularity sense as monochromes echo and recall each other in our present. Maybe it is like jazz, where certain rhythm or standards can be performed and improvised on by different musicians, each time echoing the structure but each time arriving some place else, possibly some place new.

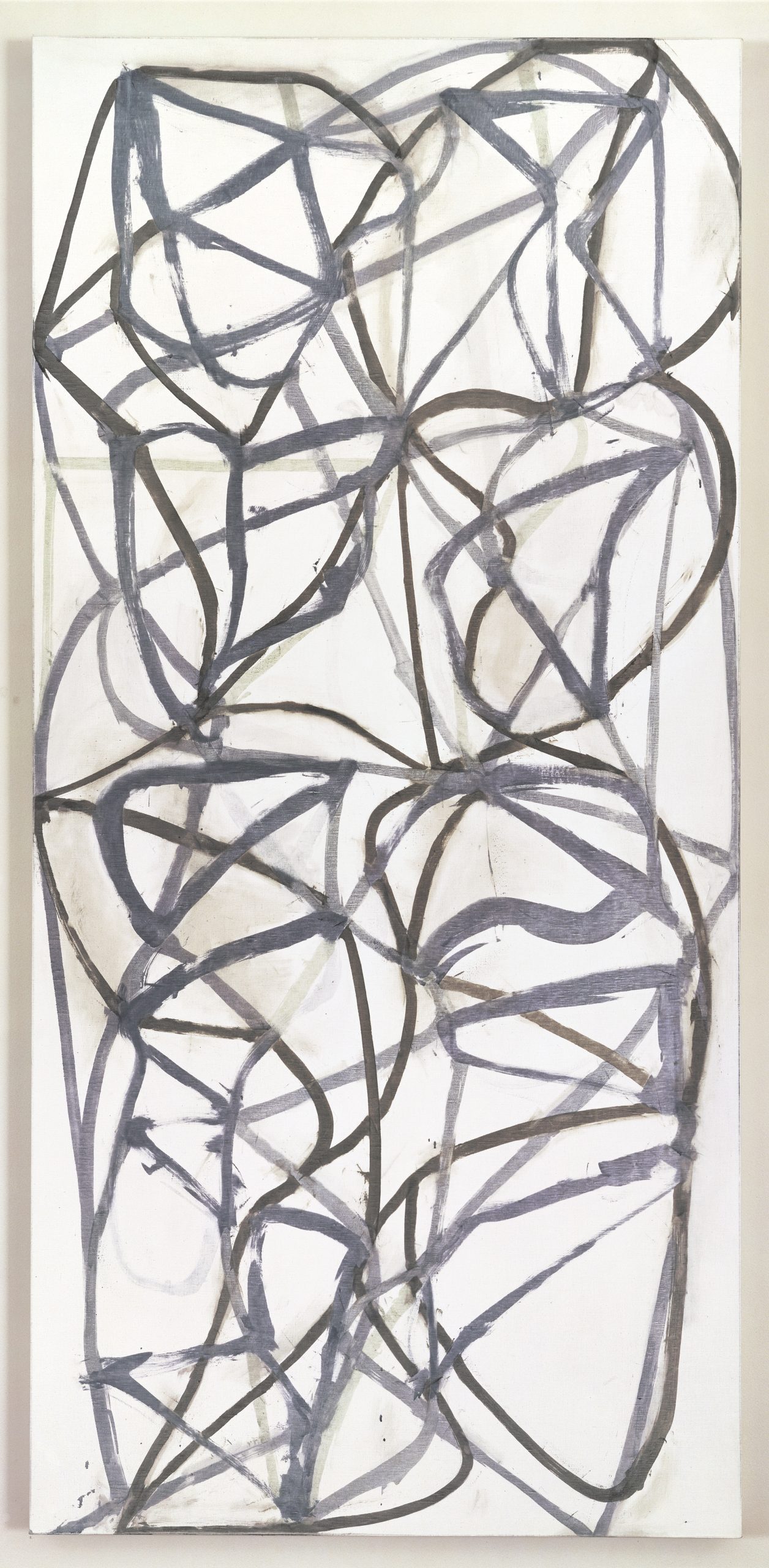

By the time of the Boston show, Marden was already turning away from the monochrome. Gestures and visual structures inspired by Chinese calligraphy and poetry had begun to appear on those lush surfaces. Instead of smooth and sullen allusion, atmosphere brought about from painting, erasure and re-painting came to the fore. In a sense his method of applying pigments in veils, layers and unveiling were still consistent, but now he was using oil paint, and placing emphasis on the drawing—leaving more traces, and in the end unveiling more than veiling. These works from the late 80s connected as much with the weblike skeins of Jackson Pollock’s drips as they do with Eastern calligraphy. Diagrammed Couplet #1, 1988-89, for instance, used the structure of Chinese poems, right to left, up to down, while pieces like Cold Mountain I, 1988-89, with their stuttering architectonic lines conjure—at least to me—the rawness of some cave paintings, even without animals or handprints. The elegant roughness of his touch suggests mountain crags or misty Chinese landscapes.

Brice Marden, Diagrammed Couplet #2 , 1988–89

Oil on linen, 213.36 x 101.6 cms

© 1989 Brice Marden / Artist Rights Society (ARS),

New York Photograph by Zindman/Fremont © 1989

If Manet’s Le Dejeuner walks backward in time with direct references from 15th century Giorgione and Raphael before swinging back round to meet 17th century Watteau, Le Nain, and most of all Courbet in the 19th, Marden’s paintings in this exhibition allude to different epochs. First, in the earlier works there is the timelessness of nature. Here the idea of the Modernist monochrome provides another notion of timelessness in its endless series and variation. In the later works, Pollock, representing another kind of modernism in the 20th, merges with Chinese calligraphy. Unlike Manet’s painting, there is a sense a circular timelessness to Marden’s endeavour.

Rosebud, 1983

Terry Myers: When I brought a group of students to your studio in Bridgehampton last summer, they were moved by your suggestion that, in the end, maybe your paintings weren’t so important.

Mary Heilmann: Well, it is a kind of deep concept, the idea that the conversation the paintings cause is more relevant than the actual ‘masterpiece’. I think of a painting a sign or a word that you put out in a conversation, and then people answer it. I mean, that’s really why I did it, all the way from the beginning.15

That idea of conversation also exists between artworks as well. Say the one between Manet with Le Nain and Courbet, etc., but also more obviously in the Connections exhibition with Marden next to Manet and Goya. Unlike the points of reference exuded by Manet or even Marden, Mary Heilmann’s work seems to spring from a more intimate place. We could say that her expression comes through adopting a more conversational tone. Trained as a ceramicist by Peter Voulkos on the west coast, who was renowned for his innovative abstract expressionist ceramics, Heilmannn eventually moved on to study sculpture with William T. Wiley, in a time when artists like Eva Hesse, Lynda Benglis, Ken Price, and her friend, Bruce Nauman, were redefining the idea of form. Of this period she says, “When I was finishing school, some things that started to come out of New York were really important for me: Dick Bellamy’s Arp to Artschwager show at Noah Goldowski Gallery; Lucy Lippard’s Eccentric Abstraction show at Fishchbach; the Primary Structures show at the Jewish Museum… I knew that my work related to this kind of thinking, and as soon as I finished school I headed for New York.”16 They were seminal shows that redefined sculpture, more specifically defining American sculpture.

Yet, soon after arriving in the city, Heilmann switched from sculpture to painting. However, notions of sculptural structure and playful, languid paint (the sort you find on pottery) still underpin her work. “First,” she says, “they are objects then they are pictures of something…”17 What are they pictures of? Like the American abstractionist Thomas Nozkowski, each work is drawn from an experience in her life—a “backstory” in her words. Though Nozkowski abstracts and distills, allowing the narrative to recede, Heilmann uses titles to keep her sources close: Our Lady of the Flowers, The Kiss, The Blues for Miles, Good Vibrations (for David), The Black Door, The Big Wave. Those are her points of departure: at arrival, her paintings exude a joyful ease, whose charm later however belies their depth of sophistication. For me, the easy attitude she takes to moving paint could be compared to the way glazes are applied to clay, like a kind of surface decoration. Nothing signifies their casualness more than when she allows paint to seep into the edges of her tape leaving her lines and shapes with uneven, serrated edges. This is not intended to suggest that there is no rigour to Heilmann’s work, rather the opposite. You feel that the paint is very close to the top, if not on the surface. This is not the same way that Marden plays with the plane. For me, it is Matisse that her work channels. Intense colour and space opened by colour but one that is demarcated by line or edge; those are the very operations by which both the Frenchman‘s and the Californian‘s paintings perform. However, where a Matisse seems cool and analytical, Heilmann is all hot and personal. The New York critic, John Yau, observes that Heilmann was one of the first artists to “absorb the lessons of Pop artists, particularly their allusions to popular culture” and it is the “synthesis of pop colour and geometric abstraction in palpably layered or optically juxtaposed compositions” that create “the absence of fixity.”18

A 1983 painting, Rosebud, is partly inspired by the martyrdom of St. Sebastian: it is an creamy all white field covered with 17 red splotches spread unevenly across. Although paintings of the Saint date from earlier, it seems to me that the dramatic ones come from the Renaissance and after. However, the only sign of this passion is the dripping red paint. Passion is certainly the theme; it is also inspired by a breakup.19 In appearance, however, Heilmann’s painting could be a leftfield pattern painting (a 70s West Coast, anti-formalist painting movement) or an oddball piece of post-painterly abstraction. That is, it is both cool and hot.

Mary Heilmann, Rosebud, 1983

Oil on canvas, 152.4 x 106.68 cms

©Mary Heilmann

Photo: Christopher Burke Studio

Courtesy of the artist, 303 Gallery, New York, and Hauser & Wirth

Its title, Rosebud, might refer to the MacGuffin in the Orson Welles’ film Citizen Kane, 1941. Rosebud was the childhood sled that symbolises the Orson Welles’ film character’s lost innocence.20 Perhaps roses blooming might be what those haptic red swirls suggest. Or is it symbolic of loss? Bleeding and weeping. And, of course, they could also be roses budding. In her impressionistic, note-like response to this particular Heilmann, the painter Jutta Koether writes that it is “[the] most emotional painting of all. Creating the crying one…ornaments and wounds. An emotional field, painted as pouring sentimentality, true sentiments, that stick around, making the painting. Making it through to an optimism, eventually. Yet is heart-crushingly pop…”21 Rosebud is, in a sense, reductive but it is also expressionistic. It’s reductive nature acts like a Marden monochrome, but in terms of evocation, as Koether correctly notes, they may be more cultural than they are artistic. It is far from the passion of a tortured saint, and far from away the Renaissance. However, in Citizen Kane, or in “blossomings” either bloody or in nature, there is a hint of the cinematic—that is a 20th century phenomenon.

Do we really see a painting in its time? No, we may be conscious of its era but we meet it in our present. That is, in a practical sense, our eyes/vision touch paint applied by a hand nearly 200 years ago. So, from the 21st century, we are, in a sense, travelling across the centuries by viewing a 19th century object with its references to the 16th and 18th centuries, as well as richly alluding to painting of its own time. Or even a late 20th century work monochrome cycling through the history of that genre.

Wondering… or coming off the wall

In his conclusory remarks on Alys, quoted in my epigraph, Boris Groys describes the present as repetitive and non-historical. It has “lost its past and future…and [is] infinitely repeated”—in other words a sort of existential Groundhog Day. Groys is talking about contemporary life, but it seems prescient in regard to ‘contemporary art’ which seems to inhabit a continuous present: one place, one time, one issue, all the time. Yes, I’m stereotyping, but speaking as a painter, I sense a shying away from painting at the moment. Perhaps its history is too storied, too full or even completed, and thus of no use value to an infinitely repeated, non-historical present that may want to reduce painting to a mere rectangle on the wall.

Rather as I’ve tried to show, it is far more complex than at first glance. It is easy to see them in the present, but the tableau could also be an opening, window, door, crack…The richness of the form, as I’ve been trying to demonstrate with these different examples and moments in time, offers another kind of mobility. It allows the mind to wander. Each stroke of paint inadvertently connects with history, connects with other paintings. Time travel while standing right where you are: looking at a painting. It is not quite like sitting at the computer screen where information on the world floods to your fingertips. Rather, it requires the mind to engage in another way…to wander. Then to wonder! And that is the exact pleasure of painting.

Now to go back in time again: a final thought. Do you know that painting came off the wall? Painting actually began on the wall—think cave painting and then church painting ala Giotto. When it came off, it was called a tableau or easel painting. The word “easel” is etymologically derived from the German word for donkey. It is the painter’s mule so to speak. Given the origins of painting, easel painting allowed artists to be on the road. There is some irony to this, as at first it was the painters that had to be mobile. They travelled to the cave or the church to make their murals. Then they became studio artists, when easel and canvases allowed the paintings instead to become mobile. When paint was made industrially and sold in tubes, another idea of mobility came about. That is when painters were more able to move outside and make plein-air paintings. We don’t actually use the words “easel painting” much anymore, perhaps it is because easels themselves are less popular. When critics were discussing Abstract Expressionism, easel painting was discussed as something they were going to surpass, as if the artists were trying to put painting back on the wall again.