Recital

This piece mixes the forms of personal narrative and academic essay with art to refract how the personal is entangled with the social in moments of individual and collective stress and grief. The piece argues that an important task in facing the cultural impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is to re-imagine our entanglements and shared imaginations so as to resist plunging into desperate future-making aimed at recovering the normal without re-evaluating our past and the narratives and practices that lead us to a point of no return. The piece moves in between reflections on my father’s death and considerations of the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic might have on international mobility, and thus on the nation-state. By doing so, the piece serves as an illustration of how the personal and the collective remain entangled even as their definitions come under pressure when the future is uncertain, and when the past, though previously taken for granted, now appears under new light. Following that line of thought, the piece concludes that art could turn on its own temporalities, and become an exercise of reimagining the past and the communities it contributed in making.

1

Chua Mia Tee. Epic Poem of Malaya, 1955. Oil on canvas, 112 x 153 cm

Collection of National Gallery Singapore

How do we experience this painting now? Do we appreciate the freedom with which the speaker shares his breath with the rest? Do we notice how they are not wearing masks?

2

On 28 February 2020 I had to do an emergency trip from Singapore—where I am based—to my birthplace, Mexico City. By then, the COVID-19 pandemic was in the wake of its first global wave. The first case in Mexico was registered hours before I landed at Mexico City International’s Airport. Little did I know, the next four weeks would change everything.

It is now 28 March, and I am writing this while travelling back to Singapore. The globe is shutting down. Borders are closing, and with them countries, cities, towns; even families are closing their own doors. Isolation and distance has surprisingly, or perhaps paradoxically, become the main strategy to defend individual and global health. And the world struggles. Some struggle to avoid falling prey to the mental and emotional strain that being isolated brings; others struggle because they simply cannot just shut down without putting their own livelihood in peril. Back in Mexico, a debate had already sprung on the media on whether self-quarantine and self-isolation are exclusive practices, marks of socioeconomic privilege in and of themselves, and therefore a terrible counter-emergency strategy for a country with an overwhelming informal economy. As I scroll on Facebook while passing the time during my layover at Tokyo Narita Airport, I hear that similar debates are springing everywhere. The pandemic is putting pressure on the conceptual and infrastructural edifice of global governance and its presumed equality.

An almost empty airport surrounds me, and besides my wife—who caught up with me in Mexico when things took a turn for the worse—all I see are people wearing masks and glasses in the best of cases, and full hazmat suits with plastic headwear in the worst. The crew for the flight to Rome is running around the airport getting as many face masks as they can. My wife and I were about to grab a pack when an Italian flight attendant grabbed it first. Let it go – my wife told me. They need the masks more. And indeed they do. The news we get from Italy are those of a country that has vanished into trauma. We walk away, and sit next to a window. A cargo flight departs, and then the tarmac lays still.

In Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism ([1983]1991), Benedict Anderson argues that a nation can be defined as “an imagined political community.” (6) It is imagined, he explains, because one will never meet the entirety of the nation and yet one will share “the image of their communion.” (ibid) I find that his insight is as relevant as ever, even as Anderson was writing in the midst of a world close to seeing the end of the Cold War, and therefore a world that had not experienced late-stage globalisation and the unravelling of the nation-state. Indeed, the turn of the 21st century saw the withering of the nation-state at the hand of globalisation and its imagined global community. And yet, the second decade of the century charged at us by surprise. Right before the plague came, the cracks in the shiny mantle of globalisation’s imaginary were already showing. Some of these cracks were visible via the notorious reawakening of hardcore and racial nationalism, sweeping across various regions of the world. We were experiencing a growing stratification and differentiation between the haves and the have-nots, refugee crises, climate change and uneven responses worldwide, etc. In academia, the rise of academic fields that focused on the cultural and political relations between an enigmatic global north and an othered global south were indeed symptomatic of the myth that a global unity always had a system of exclusivity inbuilt to the extent that its theory only appears through epistemic distancing. If by the end of the last century we could have suspected a shift towards a global and cosmopolitan model for citizenry, the 21st century was quick to remind us that we were still processing the trauma of living in a world ruled by the nation-state.

My flight is due in eleven hours, and the airport is practically empty. There are just a handful of flights departing from now till then – one to Washington D.C., another one to Houston, one to Shanghai, and one more to Rome. I suspect that they will be full of nationals going back to their home countries. During the past few days, many nations have either urged their citizens abroad to come back, or sent evacuation flights to bring them back, or both. International mobility has taken a turn towards immediate repatriation, and so the imaginaries of the nations of the world get mobilised too. Some people can travel back, some countries can afford to repatriate, and others cannot.

All this scares me. Am I being as careful as I should be? Did I disinfect my hands before I touched my mouth just now? I hear that Boris Johnson – current Prime Minister of the United Kingdom – has tested positive with the new virus. He joins a growing number of very high profile people that include Prince Charles, also from the UK, the wife of Canada’s Prime Minister, half the cabinet of the current government in Iran, internationally famous actors, and sports figures, among others. That these figures are infected gives me mixed feelings. On the one hand, if the infection is this widespread it could potentially mean that a doomsday scenario is much closer than we want to acknowledge. Yet at the same time, that these figures have been infected may also point the other way and indicate that the pandemic will simply become a common feature of contemporary life, and therefore that life will carry on, somehow, and in a way that is not too different from how we know it. There will be a pandemic, then a massive global recession and financial crisis, thousands of people will die, thousands will be out of a job, things will get critical, and then things will be back to normal. That’s how these things go. Just as how humans are explorers, we are also good at adapting. Yes, we will be fine. We will move on.

Or so I would like to think. But I also wonder whether the situation in itself is a way to move on from a past that up until a few months ago was already unsustainable. It seems that we have suddenly forgotten about all that – that we have, albeit under a clause of temporary condition, moved on from all that. But let’s be frank. The virus did not erase the present; it paused our attention to it, in any case. As we anxiously devise strategies to move on from this altered timeline—as we try to move, grab, and materialise a future that somehow resembles some degree of backward normalcy—it would appear that we have forgotten the timeline we were in. We forgot the past we came from, and while in lockdown, we may somehow have forgotten to mobilise our memories of it. How is all of that doing now? Are we being too quick to normalise pre-pandemic trauma? Are we supposed to move on from the virus? Or is the virus our window to experience time?

3

Today is my father’s birthday, but he passed away four weeks ago. He died of complications after a brain surgery. The surgery went fine—in fact, the best of the five he had to deal with for the same ailment the last fifteen years. It was his lungs. They could not take it; and then his kidneys; and then his liver; and then him whole. I was fortunate enough to be able to fly a few days before the surgery and celebrate my birthday with him for the first time in a decade. I also accompanied him in what would be his last dinner. He fell asleep and unknowingly faded off. I always knew his death would be excruciatingly painful, but the reality is that this pain was beyond what I could have imagined. It is a blast, straight to the face, a silent, absolute, and temperature-less shimmer as the realisation that nothing will be as it was before squares up in your soul. This sounds trite in words, but it is as good a description as it gets (perhaps that is why everyone says something similar when a parent passes). My father died—I have to repeat to myself—my father died. As if saying so would help me figure out a way to move on. Later today, in a couple of hours, my wife and I will have a ZOOM call with my family to drink a tequila to remember him. Tequila was the language we all spoke with him. And no, this is not stereotypical. Drinking tequila as a family is as intimate as one gets. I hate it when people think Mexicans drink tequila just because. I hate the “amigo amigo let’s drink”—what an insult. Drinking a tequila is a ritual of emotional texture; a pillar in and of our collective self. The act performs the elegance and dignity of being a Mexican (or at least, that’s how we imagine it, or how the modernist narrative of Mexico wanted us to feel). My father taught me how to drink tequila while discussing global affairs, and his father taught him how to drink tequila while discussing the history of Mexico. I imagine his father did the same with him, and so on.

My father also taught me that to live is to travel. When he was 40 and I was four, he made a working visit to the United Nations (UN), and bought me a toy replica of the UN’s flag display. Oh, how I loved that flag display. To this day, I am able to identify most flags in the world because of that replica. It was somehow metaphoric: my father had gifted me the world in its flags. This was the first memory that came to my mind the moment he passed. I realised, as he was taking his last breath, how deeply he had shaped my hunger for the world. Him dying, I was hit by the extent to which many of the fundamental decisions I have taken in life—moving to Singapore, for one—were taken as a way to embody our shared lineage of adventurers, of thinkers, of doers, of live-or-die people. A few years ago, when I had just moved to Singapore, I was invited by the UN to teach in their summer school in New York and my father met me there. We spent a few days walking around in Manhattan, getting drunk in Brooklyn, and taking photos in Central Park. Though the climax of our relationship was his death as my sister and I accompanied him, that trip to New York with him—I realise now—was the fulfilment of our bond; the seal in and of the name he gave me. I am taken aback by this chain of memories. It is as if the UN had been planted in me so that it could resurface as a memory at the time of his death and make me remember him for the rest of my life.

I have been in quarantine at home for two weeks now, receiving two or three SMS texts from the Singapore Immigration & Checkpoints Authority asking me to click on a link and report my location. I am not allowed to even step outside my door until I complete a 14-day period of forced isolation. If I do, I might lose my permanent residency in Singapore. And yet, I cannot deny that I enjoy being at and working from home. I have spent the last two weeks catching up with work, with my students, and with my writing. Naturally, I have also had time to reflect on my father’s passing. I have been pondering on what heritage, lineage, and family mean; on how we imagine our identities and communities. I tell my wife that one of the most significant cultural differences between how she and I think about family is in the name. Indeed, what is in a name. Coming from a Malay lineage and tradition, she does not have a surname. She is named as the daughter of her father, and so her father’s first name becomes her family’s synecdoche. In contrast, I do have a surname; two in fact. Surnames in my culture are what makes you part of a community the moment you are born. You have a Cervera bum – my wife often jokes. But I also have the Cervera culture, the vital know-hows that I learned and that were passed to me, assembled as an affect that defines what a Cervera is or how a Cervera feels or thinks—the technique of being Cervera, as many theatre and performance scholars would have it. My grandfather too was a traveller, and all my family work in TV – except me, that is. I opted for theatre thinking that I was the black sheep, but I soon learned that my grandfather, my father, and one uncle had all started off as actors before becoming TV people. This is the community I come from. This is my past, and its imagination is what gets mobilised upon my father’s passing.

The UN—what an archetype to seed into your child. Funny thought to entertain these days, too. I wonder how the UN will be remembered after this; or its World Health Organisation, for that matter. There is a way in which we idealise our past and justify its existence and consequences to frame a narrative of life. In hermeneutic psychology, specialists emphasise the value interpreting the lived experience through various artefacts that one produces to articulate its meaning. And indeed, the process I am going through—making sense of the UN anecdote through writing it, for example—is pretty much a hermeneutic endeavour. I try and re-interpret my life vis-à-vis my father’s, which is also making sense of the now—and the future—in relation to a perceived past. It entails untangling what it means to have that father to me specifically, and making sense of how what I have interpreted to be my heritage, has had an impact on my present, determining too—who I project to be in the future. What is the extent of my authorship in the project I call I when placed in relation to the ways in which others have interpreted me? This could also be a question posed to any nation-state that participated in the efforts of creating and maintain the UN. What authorship does a nation-state have on its own identity in relation to how it is perceived and expected to behave by other nation-states? How is that identity being mobilised in times of social sickness and mass death?

I am interested in remembering my father to understand the ways I have narrativised an ideal story of my family and my heritage: the myth in the Cervera name, if you will. I am interested in reflecting on this because as much as I mourn my father and deal with his absence, I also realise that I tend to forget the extent to which he also was part of traumatic experiences that made me leave Mexico in the first place. This is personal I admit, but what isn’t personal nowadays? As the boundaries between the private and the public become blurred during our remote socialising and work, as we peer into each other’s homes and rooms, and as we become the historic subject that will determine the narrative that emerges out of the pandemic, what isn’t personal indeed? Even the UN can be a personal story in times of death and distance.

Band of Migrant Workers perform a song at the

Migrant Worker Poetry Competition Finals. 2014

Courtesy Global Migrant Festival. Photo: © 2019 Abhineet Kaul

What poetry will be written by migrant workers in Singapore after their experience with COVID-19? How will that poetry be shared?1

5

What communities are being imagined, assembled, and mobilised in times of shared yet uneven sorrow? Trauma, even when globally shared, is personal. While trying to seize the world from the confines of my desk and my home, and to process my loss, I check the latest updates on the pandemic. I see that the US doubled its cases in a week, and that as of today, we are nearing two million infections globally; that the dying die alone, and that the dead cannot be buried by their families. I hear the current president of the USA is accusing China, and I see China sending medical aid to Mexico as a counter-message. Once symbols of national identities, airlines are now transport for an emerging global network of medical supplies. Global leaders meet via videoconference, just as I have been doing with my students. Minorities are getting affected much more than the wealthy because even when they ought to stay put, they cannot not move. Not moving is now a mark of wealth and privilege. Mobility is essentially left for the poor.

The pandemic mobilises communities, albeit in a different way. Its presence fractures the individual and the collective. Surely, we are bound to witness a wave of political romanticism as economies re-boot and concerted attempts to go back to normal are put in place. We are bound to see images, hear songs, watch movies, sit in plays, read books, and experience art that—state-sponsored or not—express the trauma of the pandemic. Many of them will do so by highlighting the collective subject and its importance in the achievement of the greater good. We will see narratives and iconographies that highlight the sacrifice of the one for the many, that embolden the charisma of those leaders who managed to keep their nations safe, and that passionately represent the value of post-pandemic industrial life. And these narratives, images, and representations will carry with them pandemic-infused hermeneutics, which will be the base we use to remember and re-imagine the communities we come from. These will also contribute to how we re-imagine the boundaries between me and you, us and them, the personal and the public, touch and screen, and between distance and proximity.

Mobility, like the virus, blurs the distinction between the micro and the macro, between the personal and the collective, and between the part and the whole. A few weeks before my father’s death, I came to the realisation that I had, and continue to occasionally experience, migratory grief. This is a condition in which the migrant endures a mourning process that is naturally implied in any migratory experience. The phenomenon stems from the sorrow felt upon leaving one’s family, friends, and country behind, and consequently missing their lives and life in the country one was born in. Fundamentally, it also means confronting and acknowledging the possibility that death might occur on either side without having the chance of saying goodbye. I realise how extraordinarily lucky I was to have that chance, right in the rise of a global pandemic, and to be able to travel to the other side of the planet to bid my father farewell. In hindsight, as I reflect on the huge difference between travelling to Mexico in late February of 2020 and returning to Singapore in late March of the same year, I am shaken to think just how tight the window I had was. That window is gone, and while for me it worked out with just the right amount of time to have a last memory of my father and be able to accompany him in his deathbed, there are many people around the world that did not enjoy that benefit, even when living in the same home—or worse, when they were caught apart because of the necessity to labour elsewhere.

The way I remember and interpret the trauma of the pandemic will forever be entwined with the trauma of losing my father. Yet, my sorrow, even when influenced by an overwhelming sense of permanent threat, will never be the same as someone who did not bid their father goodbye on the same day I did because they were isolated or far away. How do we re-imagine communities today, in light of the fact that the pandemic set us apart more than before? As I write, Singapore is facing a third wave of contagion, now within the migrant workers’ community. Yet, unlike the previous waves, this one is being framed with clear distinctions as the number of infected people in the community is reported as a separate number than those diagnosed in migrant workers’ dormitories. Indeed, my experience of migration, and of life and death is substantially different than theirs.

We were already socially distanced before social distance became the remedy to a virus. And it seems as if we forgot this because the pandemic is mobilising a new imagination of community. At first sight, on the surface, this re-imagined community is marked by transpersonal camaraderie and “human spirit”, and enacted by the ghostly “we” that will come through this together. But upon closer look, one can see that as isolation becomes the most accepted medicine, national isolationism will become a scaffold for the narratives that nations will deploy to maintain the symbolic boundaries of their identity and power.

6

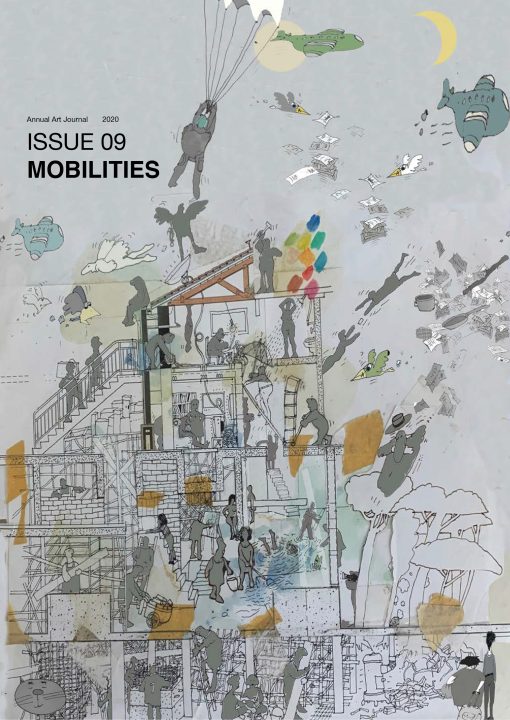

As we face the task of having to move on, re-imagining the past, it seems to me, is key. The answer to the question of what art can do in such a scenario is self-explanatory. Intervening with hegemonic narratives and re-imagining the human condition has been the task of artists in many historic moments. But perhaps the current situation lends itself to interpreting our past differently. If anything, art could now become the exercise of reimagining the past and encourage us to change timelines. How may we re-interpret a gathering of people? The family? The nation-state? Mass migration? The UN? How will we re-imagine our communities, and the links that make us be one?

Kamini Ramachandran performing storytelling in front of Boschbrand

(Forest Fire, 1849 by Raden Saleh) in 2017

Courtesy Kamini Ramachandran (Moonshadow Stories)

What are the stories we will tell ourselves about this time? How are those stories going to be passed from generation to generation?2