in memory of Ralph Rumney

The City as Playground

Walking, running, and other variations on sport and game playing, including swimming, have been integral to the expanded practice of a growing number of international artists in recent years. Walking in particular, connects the Dadaists and the Situationists from the early and mid-20th century to contemporary art tendencies. But we can go as far back as Renaissance pageants and processions to see art and human movement coming together. And while we are there, it is worth remembering the playful practical jokes that Leonardo da Vinci was famed for playing on his fellow artists and patrons, gleefully described by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (published in 1550). Particularly memorable was his habit of leaving visitors in one room of his house, then going into the adjoining room and using a pair of bellows to inflate a cow’s intestine like a huge balloon, often terrifying the guest. Moral of this story: one person’s play can be another’s fear.

Much closer to the present, by the 1970s, Nesa Paripovic, an experimental Serbian conceptual artist, made and filmed performative actions based on walking. As Felicity Fenner describes in her recent and very timely book Running the City Why Public Art Matters:

In one of his most famous works NP 1977, the artist, well-dressed in the attire of a Parisian flaneur, can be seen walking in a straight line through the centre of Belgrade. To prepare for the walk he drew a line through a map of the city, from the outlying suburbs straight through the very centre. As he follows that line, he stops for nothing and noone.1 Maintaining his course with complete disregard for private property or the urban planning infrastructure designed to control pedestrian thoroughfares in city streets, he climbs over fences and other obstacles in his path, strolls though playgrounds, and jumps over walls and onto roofs. All the while the artist mutters to himself, looks increasingly dishevelled2 and occasionally sits down for a cigarette break. Undertaken in this unorthodox manner, the route seems more labyrinthine than linear. As subversive as it is absurdist, this highly experimental work also provides a unique snapshot of Belgrade at the time, taking the viewer through working-class and well-off suburbs and revealing everyday details in the spirit of [Guy] Debord’s psychogeographic explorations.3

Felicity Fenner

Flash Run, Sydney, Australia, 7 June–20 July 2013

From Running the City: Why Public Art Matters

What is Psychogeography and who were the Situationists?

The Situationists (SI: Situationist International) were a pan-European group of artists, notionally led by the above-mentioned Guy Debord, and evolving out of the Lettrist International. They (a small group of less than a dozen) formed at a conference in Cosio d’Arroscia, Italy, in July 1957. Their stated aim was to eliminate capitalism “through revolutionising everyday life.” One of the main tools to do this came through harnessing a sense of play and of spontaneity. The Scandinavian artist Asger Jorn,4 a founding member of the CoBrA5 group of artists was one of those who joined on that momentous day. Others, as described in Tate Modern archives “were made up from two existing groupings, the Lettrist International and the International Union for a Pictorial Bauhaus. As well as writer and filmmaker Guy Debord, the group also prominently included the former CoBra painter Asger Jorn and the former CoBra artist Constant Nieuwenhuys [usually just known as Constant]. British artist Ralph Rumney was a co-founder of the movement.”6

I knew Ralph Rumney well. We became very close friends in the late 1980s, through to his death in 2002, aged 67. We completed many nocturnal explorations of different cities. The creation of Psychogeography, especially where ‘play’ is the guiding principle, is as much an invention of Ralph’s (I find it hard to refer to him as Rumney—too formal for the most informal of sentient beings) as it is of Debord’s.

As Lori Waxman writes in her page-turner of a book, Keep Walking Intently:

One of the greatest game players of all was Ralph Rumney, sole member of the London Psychogeographical Committee, an organisation he made up on the spot at Cosio [d’Arroscia in 1957]. Lost in Cologne, without a chart or any understanding of German, he used a map of London to find what he was looking for: Daniel Spoërri’s artwork-cum-restaurant and the Fluxus artist George Brecht. [On another occasion] drunk one night in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, he and a Swedish friend, having been kicked out of their hotel, decided to split up, one to the left, the other to the right, and meet in New Delhi.7 His friend made it all the way to India, only to find that Rumney had gone to Sicily and stopped.8

Chance and spontaneity play a huge part in the many art movements and tendencies that Waxman examines in her book. And it was through chance that Ralph and I first met in 1988 in The Plough Tavern, opposite the British Museum in Bloomsbury. I was on my way to the Cologne Art Fair which opened the next evening. I was looking for Peter Townsend, editor of Art Monthly magazine,9 used that pub more-or-less like an office. I was hoping for a commission or two. I was disappointed and surprised to find that he was not there. Then I spotted Jack Wendler, Art Monthly’s publisher who in the past ran a successful New York gallery for many years. Sitting next to him was a tall man, who to me looked elderly,10 dressed entirely in denim except for a black beret. Jack, with his cycle helmet and trouser clips on the table, ushered me across for a drink. Several hours later, Jack had cycled home, and Ralph and I were still talking. A whole new world was opening up to me. Eventually Ralph said, “It’s time we went on a dérive.” What’s a dérive, I wondered silently, suspecting I would soon find out? It was my first introduction to the art form. We kept walking almost until dawn, weak sunlight eventually lightening the Thames. Weaving through backstreets, stopping at late-night cafes and bars, ducking into theatres for the final (free) twenty minutes of a play, jumping on and off night buses at random…talking endlessly about art and ideas. He would be both delighted and amused to know that in 2023 a few voices on social media predict he (and his philosophy of game playing) will be to the 21st century what Marcel Duchamp was to the 20th. That night, we made plans for Ralph to come up to Edinburgh to satisfy his desire to meet and interview Ian Hamilton Finlay whose various battles from his moorland home and garden of Little Sparta I had been chronicling over a period of months for Art Monthly.

Ralph moved, as his friend Guy Atkins wrote, “between penury11 and almost absurd affluence. One visited him in a squalid room in London’s Neal Street, in a house shared with near down-and-outs. Next, one would find him in Harry’s Bar in Venice, or at a Max Ernst opening in Paris. He seemed to take poverty with more equanimity than riches.”12

Over the years I heard all the much-repeated stories—playing chess with Duchamp (“He was such a gentleman, I was young and he always lets me win”); his marriage to Peggy Guggenheim’s daughter Pegeen. Her eventual suicide, successful, as Ralph told me in an interview,13 on the 17th attempt. All this was confirmed and expanded upon in Waxman’s book:

Rumney even made a game of grave situations. After his wife Pegeen committed suicide, her mother Peggy Guggenheim had Rumney followed by private detectives [in Paris] while trying to bring a case against him for aiding and abetting her death. (It was eventually dropped.) Since they were trailing him everywhere, he walked a lot, wearing the PIs out by making them go on dérives without knowing it.14

Later, she describes the most fabled of Rumney’s dérives: “The Leaning Tower of Venice presented a psychogeographical investigation of the floating city. The first page declares: ‘It is our thesis that cities should embody a built-in play factor. We are studying here a play-environment relationship.’ ”15

This, astonishingly, from over sixty years ago.

Playful interjection16

I’ve just been Googling Ralph and have discovered an astonishing document. I was pretty sure he was the son of the Vicar of Wakefield (he was). My search was simply “Ralph Rumney son of the vicar of Wakefield.” About four listings down I came across this link:

https://www.editions-allia.com/files/pdf_468_file.pdf

This internet dérive had taken me to a catalogue of a posthumous Ralph Rumney exhibition held in Paris in 2010.17 In addition to photographs of the rare, physical artworks that he made18 there was a shot of his passport, multiple images of him playing chess, and several short essays in English written by friends and collaborators. The leading essay was published in French and was written by Michèle Bernstein. I am eager to get it translated. Bernstein was a founding member of both the Lettrist and the Situationist movements19 and one of the main contributors to the journal Potlatch. She married, first, Guy Debord and many years later (long after Pegeen’s suicide) became the third wife of Ralph Rumney. Much earlier, Debord had expelled Ralph from the Situationists for submitting his psychogeographical report on Venice a day late.

Venice, appropriately for a car-free city, has been the site of many walking projects since Ralph Rumney, including Sophie Calle, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller, Larisa Kosloff, and my own Word of Mouth project.20

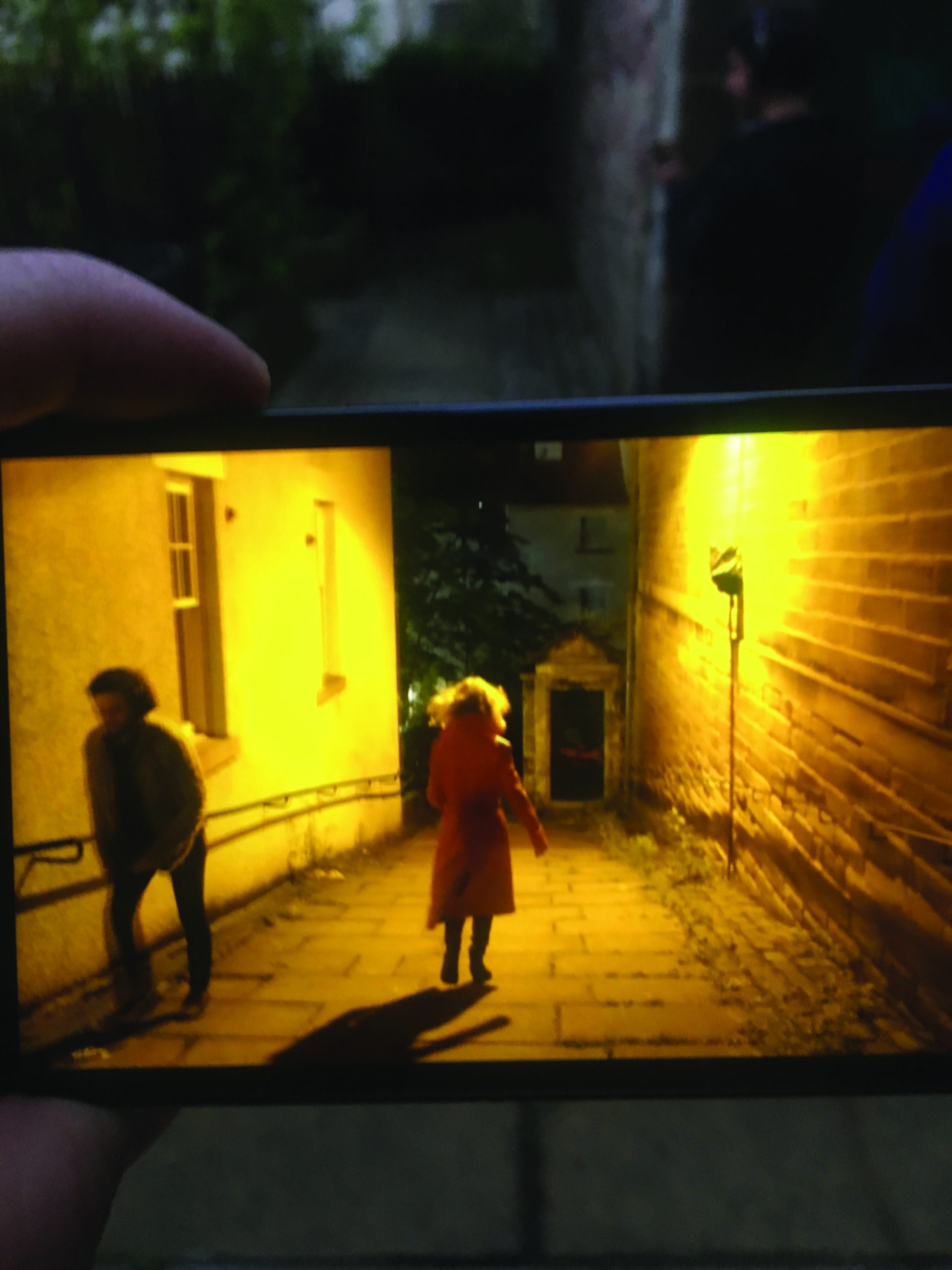

Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller

Night Walk for Edinburgh (Scotland), 2019, duration 55 minutes.

Photo: Dr Peter Hill (this walk and others can be accessed at:

https://cardiffmiller.com>walks>night-walk-for-edinburgh)

Influencing Contemporary Tendencies

The Situationists gave us two major devices (both playful in their intent) to navigate and engage with the mid-20th-century life of the city. These were the dérive (at its most basic level an unplanned ‘drift’ through the city during which decisions were taken spontaneously and ‘getting lost’ was seen as an achievement to be welcomed rather than feared); and the detournement, when a physical object (and sometimes an idea) was ‘turned’ into something else, to achieve an entirely different purpose. Both of these elements were, in the decades following, to influence the student demonstrations in Paris and England in 1968, and the Punk movement in music and fashion as envisaged by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren in mid-1970s London. They continue to influence young artists and curators in the 21st century. For example, in Paris in 1968, students overturned café tables (put them through a détournement) and piled them high to form barricades in laneways as a barrier between the riot police and themselves. Australian cowboys (known as “boundary riders”)21 used their belt buckles to open bottles of beer, another detournement.

Michèle Bernstein famously published two détourned novels through Buchet/Chastel, whose moderate success “helped her convince her publisher to publish Debord’s major theoretical text, The Society of the Spectacle (1967), despite its non-commercial nature. In All The King’s Horses (Tous les chevaux du roi, 1960; republished Paris: Allia, 2004) and The Night (La Nuit, 1961; republished by Allia in 2013), Bernstein tells the same story in two different ways, adapting the plot of Les Liasons Dangereuses to create a ‘roman à clef despite itself featuring characters based on herself, Debord and his lover Michèle Mochot.”22

Over four decades after the student demonstration in Paris, in a work called Track and Field at the 2011 Venice Biennale, the artist team of Allora & Calzadilla ‘turned’ a 52-ton tank from the era of the Korean war, upside down and fixed a treadmill to its chassis. A classic détournement on an ambitious scale. This was the contribution for that year’s United States’ pavilion. Every day, outside the pavilion and throughout the six-month event, Olympic athletes in their uniforms took turns to run for 30-minute sessions on the ‘tank-treadmill.’ Meanwhile, inside the pavilion, further détournements between sport and contemporary life were made.

Reviewing these works in The New York Times in 2011, Roberta Smith says:

Body in Flight (Delta) and Body in Flight (American) are on view in the two galleries flanking the vestibule. As in Track and Field, performances by trained athletes, in this case gymnasts, provide momentary life. Here polychrome wood replicas of airplane seats—a Delta first-class flatbed seat and an American business-class reclining seat in sleep-ready position—serve as gym equipment while also reflecting both the luxuries and the class distinctions of air travel. The Delta seat functions as a balance beam for a female gymnast whose sensuous performance evokes an attractive model demonstrating appliances or cars at a trade show. The male gymnast uses the American seat as a pommel horse, and the loud thumps of his many energetic jumps, mounts and dismounts, executed without benefit of padding, provided a painful sound accompaniment. It seemed like debilitating, delegated endurance art.23

Other artists, such as the ever-playful Martin Creed, have used professional sportspeople in their projects, most notably in Work No. 850. He tasked professional runners with running through Tate Britain “as fast as they could, in a straight line, as if their lives depended on it.”24 This introduced not only movement to the usually static gallery, but also smell, through the artist’s sweat and perspiration, and sound through the slap of feet on marble. Both of these projects are also well-documented in Fenner’s Running the City.

On our (always playful, but deadly serious) route to the core of psychogeography, we should take note of some of the tendencies and individual projects that set our parameters. And we should never lose sight of that great Situationist dictum, “The Map is Not the Territory.”

Artists’ bars around the world are great places for chance meetings, as we have seen, and playful encounters. I remember in Amsterdam in the late 1980s meeting a South American arts entrepreneur called Eduardo Lipchitz Villa (descendant of the great Cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz) in a cafe called Het Paleis, close to Dam Square. He told me how he was trying to gain permission for a NASA satellite to film Ulay and Marina Abramovic walking along the Great Wall of China. I don’t know whether the satellite ever materialised, but Fenner also describes how in 1988 they deliberately ended their personal and professional relationship “beginning from opposite ends 5000 kilometres apart and crossing in the middle to say goodbye.”25

Lee Wen

Yellow Man, 1992–2012

Photo: Courtesy of iPreciation Gallery, Singapore

In Asia, Fenner writes, “Singaporean artist Lee Wen’s Yellow Man is a politically motivated performance involving walking through the city state, his semi-nude body caked in yellow pigment; and for Cities on the Move [South Korean conceptual artist] kimsooja undertook an eleven-day, 2727-kilometre performance walk through Korean cities carrying large bundles of cloth which referenced, among other things, the displacement of peoples.”26

Elsewhere in Running the City, Fenner writes pen pictures in dazzling prose of a variety of contemporary artists who expand the field of walking and running as an artwork. These range from the bigger-than–film-scenarios of Canadian partners Janet Cardiff and George Burres Miller, in which real fear is often induced in participants who undertake their “directed walks,” to the many public projects of David Cross in Australia and New Zealand, and Swedish artist Per Huttner’s extensive Jogging in Exotic Cities projects. The latter artist is described as “an absurdist alien runner.”27

David Cross

Level Playing Field, Scape 7, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2013

Commissioned by Scape Public Art, curated by Blair French

Photo: Shaun Waugh

Spontaneity

Having to take quick and spontaneous decisions can produce some of an artist’s best works.

In 1921, Man Ray—having relocated from New York—after months of trying, finally secured a solo exhibition in Paris. His fellow Dadaist Tristan Tzara wrote the press release for the show, as described by Mark Braude in his recently published biography Kiki Man Ray.28 It was “pure Dada hokum: Man Ray, before stumbling upon Paris, had been ‘a coal miner, a millionaire several times over, and the chairman of a chewing gum trust.’”29

Braude reports that “Man Ray failed to attract any buyers despite pricing his work aggressively…the show garnered only a couple of sentences in the press.”30

However, “The best thing to come from the exhibition was a work inspired by Erik Satie. He showed up a few hours before the opening, more undertaker than composer with his black bowler hat, black umbrella, black frock coat, silvery goatee, and pince-nez. Meeting Man Ray for the first time Satie challenged him to create an object on the spot for the show. They went together to a hardware store where Man Ray bought a flatiron and some shoemaker’s tacks. He glued the tacks to the iron’s base, creating a compact machine for destroying clothes, which he titled Gift.”31

This readymade sculpture was lost during the run of the show. However, his photograph of it became a Surrealist icon, and as Braude remarks, “By Man Ray’s twisty Dada logic, this secondhand representation exuded even more aura than the original.”32

Another example of artistic quick-thinking happened on one of several crazy dérives I had with the German ‘Bad Boy’ artist Martin Kippenberger. It was at the first Frankfurt Art Fair (1989) and we were in a bar (of course). Stopping mid-sentence, Martin suddenly leapt across the tent to retrieve a white box that a waiter was throwing out. On its exterior, the word Martini was printed in large black letters. It probably held six bottles. With a wicked smile on his face, he put the box on his head and, raising his left hand obscured the last letter i. As if by magic, I was looking at the word Martin.

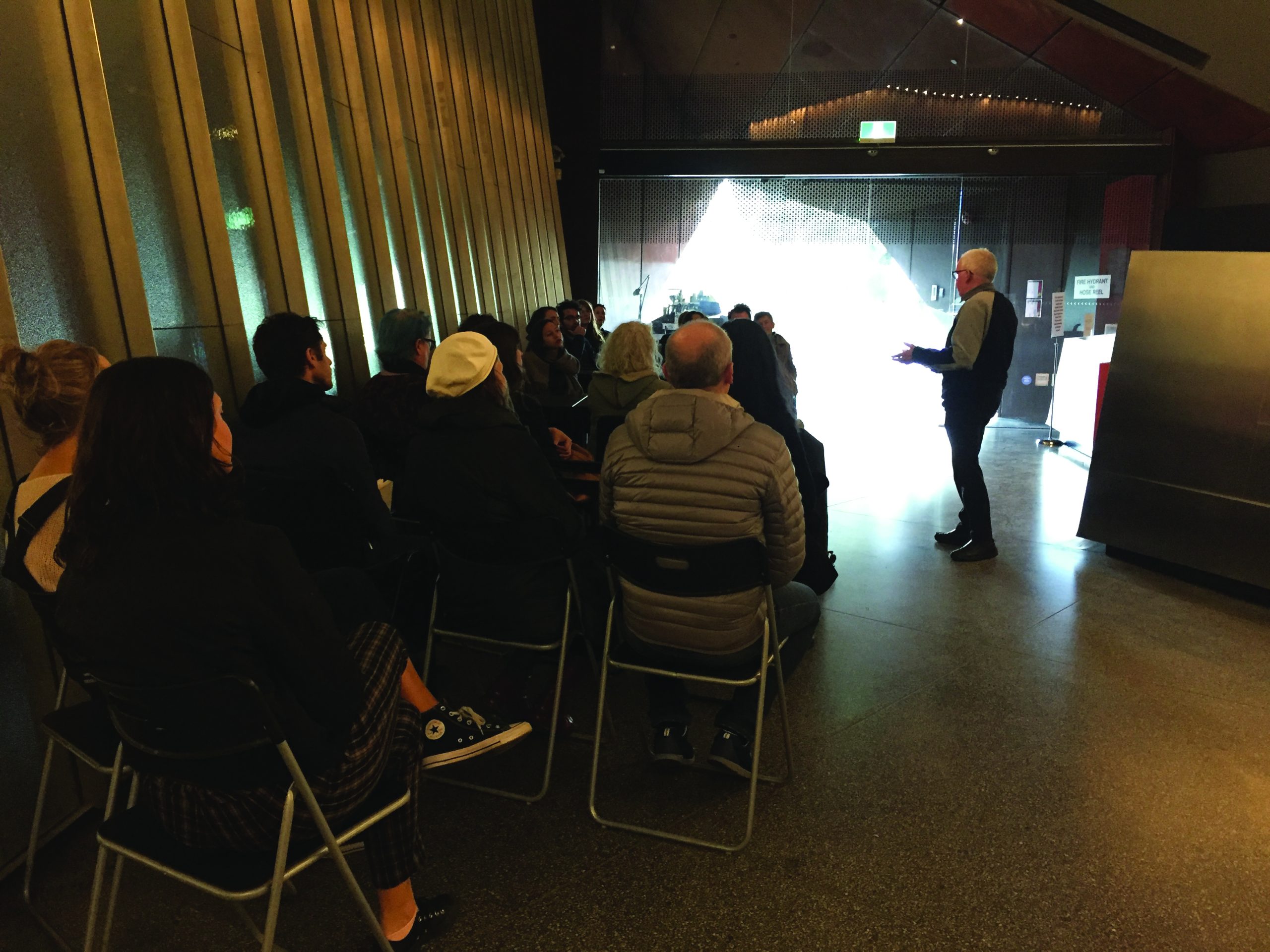

“The Directed Dérive”

A few years ago, in a COVID-free world, I was commissioned by ACCA (Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne) to construct one of my own psychogeographic walks, taking inspiration from their then current exhibition of around a dozen artists who worked in Mexico City. Titled, Dwelling Poetically: Mexico City, a case study, it included works by Francis Alÿs, Andrew Birk, Ramiro Chaves, Martin Soto Climent, Abraham Cruzvillegas, Chelsea Culprit, ektor garcia, Yann Gerstberger, Jaki Irvine, Kate Newby, Melanie Smith, and Isabel Nuño de Buen. It was developed by guest curator Chris Sharp.33

This project is an example of how a dérive can be ‘directed’ by an artist yet remain “a magical mystery tour” to the participants being directed. Seventy percent of the dérive might be planned in great detail but 30 percent remains spontaneous. Many of these artists hailed from other countries but had made their home base in Mexico. One such was the Belgian Francis Alÿs. His videoworks were a useful introduction for my participants to the possibilities of psychogeography, especially one where he walks through the streets of Sao Paulo, Brazil, with a leaky can of blue paint, leaving a thin but colourful spoor across the city.

For the ACCA project, I wanted the participants to navigate the gap between visual art and literary fiction, to initiate their own Superfiction project, and to workshop this over three hours with each other, through walking and talking.

I directed the Events Curator Anabelle Lacroix to deliver a one-sentence summary of the projects of each of the 12 participants in the exhibition. She did this, as I expected, brilliantly. This allowed a complete tour of the show to be made in under 10 minutes. At the time, by chance, I’d been reading Last Evenings on Earth (1997), the book of dark and edgy short stories by Roberto Bolaño, who, fittingly for the project, spent most of his childhood in Mexico City. Better still, there were the same numbers of artists in the show as short stories in the book.

Peter Hill runs Psychogeography Workshop: Last Exhibition on Earth at ACCA, Melbourne, Australia, 2018

left Peter Hill instructs participants on Psychogeography and the (non)rules of the game

right Peter Hill leads the group around Melbourne CBD

Photos: Anabelle Lacroix

Returning to the foyer of ACCA, I handed each of the 25 participants34 an envelope containing just the first page of one of the short stories (this meant at least two participants would be getting the same short story page). I gave them a few minutes to read their texts, and then to choose an artwork from the show to pair with the text. We set off on our dérive with everyone instructed to remain silent for the outward journey and to use the walking time to reflect on what kind of artwork they would plan to make at a later date. It could be entirely text-based or object-based, but I hoped they would come up with solutions that bridged the gap between disciplines. Unknown to the group I had researched in advance two exhibition openings that would be happening in Melbourne that afternoon, with wine, conversation, and stimulating art. We attended these and then headed back to ACCA. One of my spur-of -the-moment decisions was to line up the entire group outside the second gallery in order of height, from tallest to shortest. I then paired them up with whoever was next to them and encouraged them to discuss their ideas as the drifted back to ACCA by whichever route they chose. This did two things: it meant they were probably paired with a stranger; and it meant being roughly the same height they had mouths and ears at the same level, useful with the noise of trams, crowds and traffic on a Saturday afternoon. Back at ACCA they used the final half hour to write up a plan of what they intended to make/write. Other devices I have used—often combining lectures with derives—include:

Navigating the city by changing traffic lights, and always going with whichever light is green;

Stopping the lecture three-quarters of the way through, at the point where I am describing dérives, and inviting the audience to put down their bags and “follow me”; I then lead a dérive through the city;

Arriving at a pre-planned gallery space where I have arranged small canvasses for the participants to work on in acrylic paint, sometimes “sitting inside a three-dimensional painting” and making paintings about painting;

In 1999, during a project at The Museum of Modern Art (Oxford, UK), I arranged to be kidnapped from the podium by three students dressed like terrorists, dragged into a waiting car and driven with my curator to Heathrow airport from where we flew to Stockholm and continued the project there.

The Next Step

Professor Antoinette LaFarge, based at University of California, Irvine, recently published the first academic book on Fictive Art (a tendency I call Superfictions). Titled Sting in the Tale: Art, Hoax, and Provocation,35 the hundreds of examples she details exhaustively, in six well-defined parts, range from Marcel Broodthaers’ The Museum of Modern Art, Department of the Eagles; and David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles; to Angela Washko’s The Game: The Game (1918); and Guillaume Bijl’s Four American Artists (circa late 1980s).36

According to LaFarge, in the case of Bijl, his primary intention was “to satirise the recent rise of Neo-Geo abstraction as typified in the work of artists like Jeff Koons and Peter Halley. The works of [fictional artists] Janet Fleisch, .William Hall, Sam Roberts, and Rick Tavares thus bore many hallmarks of Neo-Geo work, including bright geometric elements alongside everyday objects such as baseball bats.”37

We immediately see how satire and parody can combine with narrative and biography in a way that is typically playful. But rather than the playfulness of the playground or the dérive through a city, it is a playfulness that exists in one’s own head, sparked by the use of fictive objects and moments in time (in this case contemporary art practice), existing in the gap between installation art and literary (or junk) fiction.

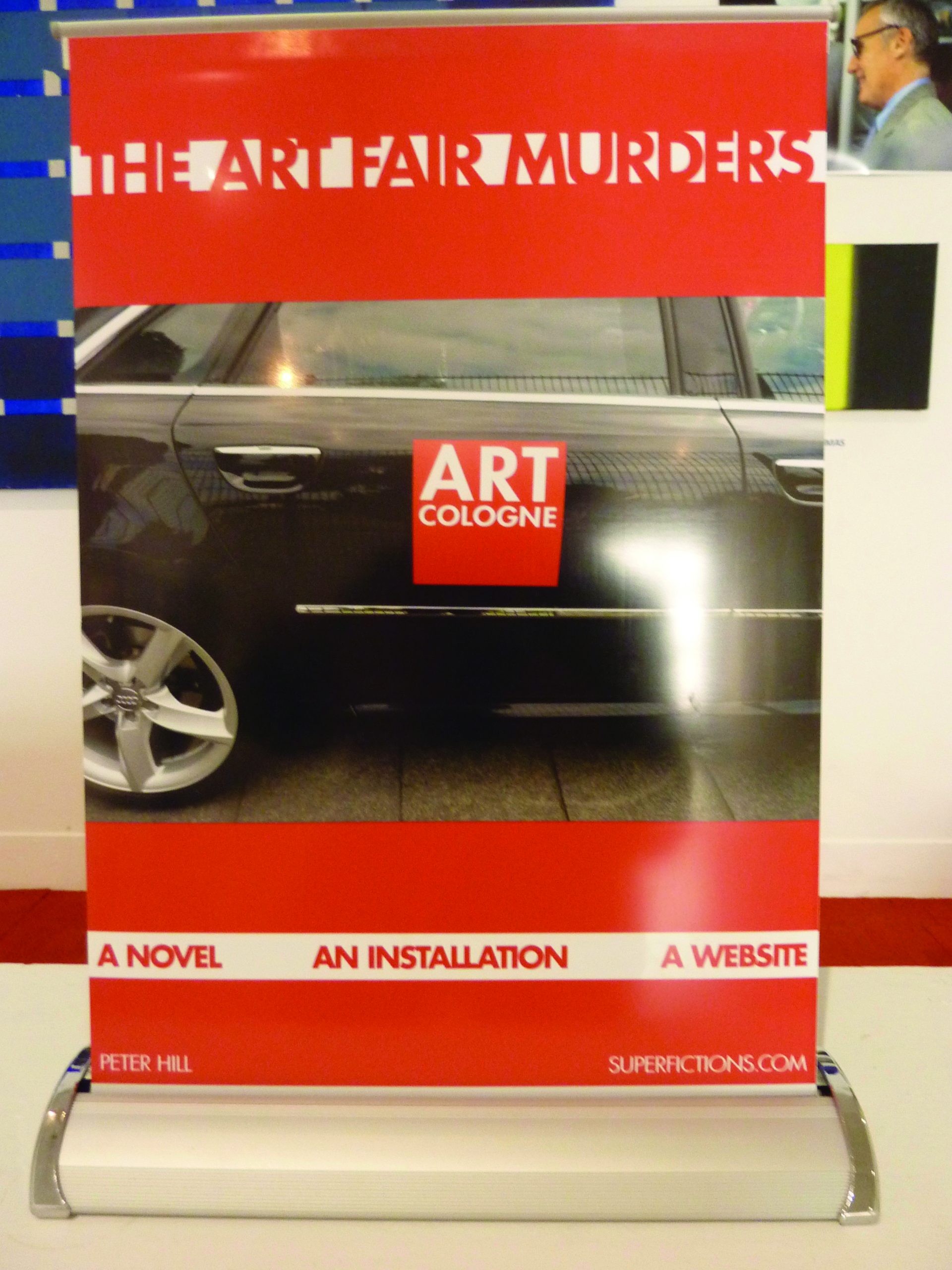

Peter Hill, The Art Fair Murders,1989–ongoing, detail of banner within larger

art fair “slice” (2014), at 45 Downstairs Gallery, Melbourne.

Photo: Dr Peter Hill

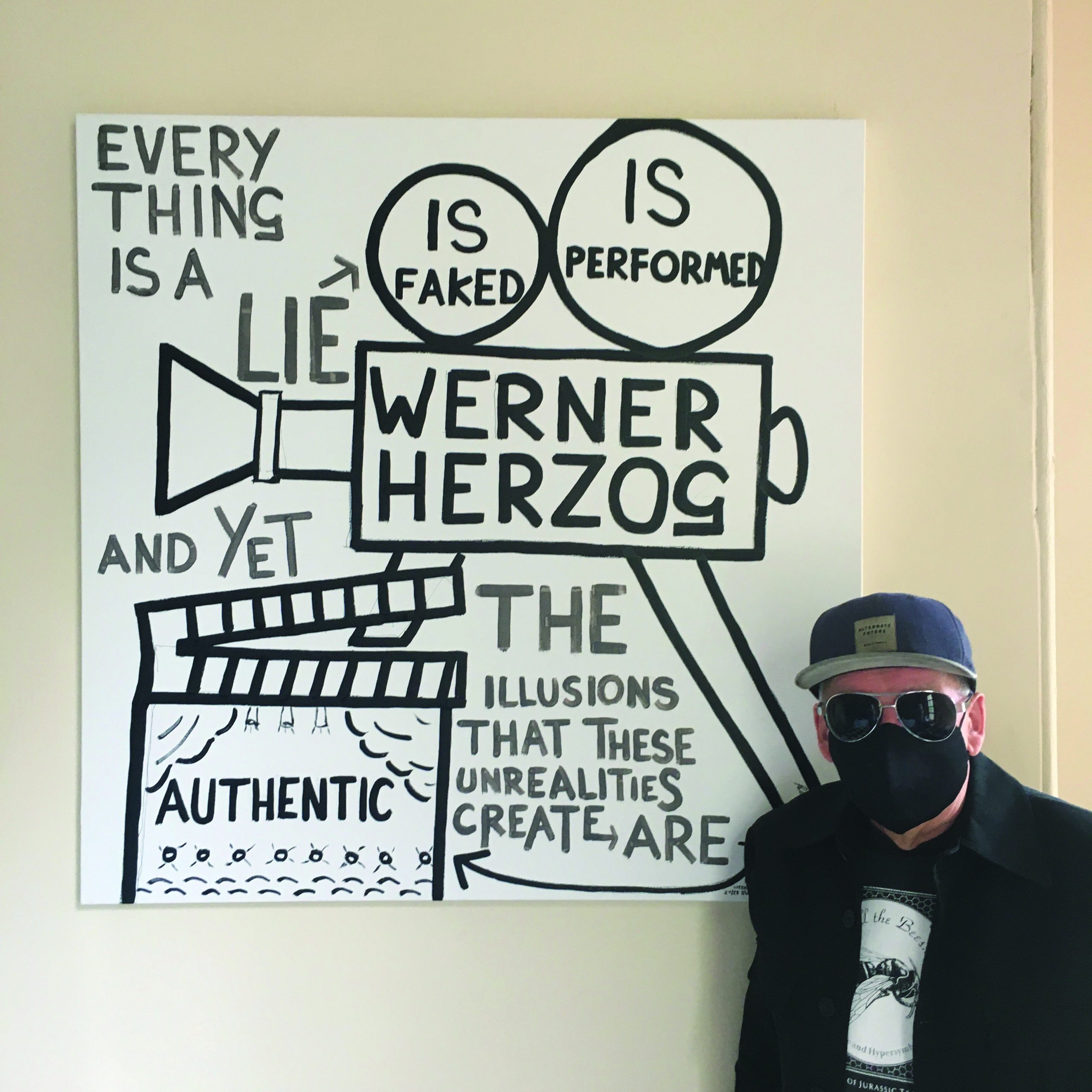

Peter Hill working as the Superfiction artist known as Stickleback,

a character in The Art Fair Murders and The After-Sex Cigarette (both 1989

ongoing). Painting made during COVID lockdown, Sydney, 2020.

Acrylic on canvas, 1m x 1m. Photo: Dr Peter Hill

In my own ongoing The Art Fair Murders, which speculates on a serial killer being loose in the art world, killing a different art world personality (artist, dealer, critic, collector, auctioneer etc) at each of 12 ‘real’ art fairs that were mounted in 1989 in cities as varied as Cologne, Chicago, London, Hong Kong, and Amsterdam, I created a love triangle between two abstract artists Herb Sherman and Hal Jones who fight for the love of Mexican-American graduate student Lisa Fernanda Martinez.38 They became literary devices as a way of introducing ‘plot’ to the act of abstract painting, extending the way ‘narrative’ had previously been fused with lyrical abstraction.

Peter Hill working as the Superfiction artists Herb Sherman and Hal Jones,

characters in The Art Fair Murders: Aesthetic Vandalism, 1989-ongoing.

Margaret Lawrence Gallery, Melbourne, 2012

I have recently been looking at a Melbourne-based artist Nick Selenitsch39 whose work has evolved over many years, from examining the physicality of play (playgrounds, sporting events, sport equipment, games etc) to sophisticated, and often very funny, fictional constructs.40

In a recent solo exhibition at Savage Garden, Melbourne, in November 2022, I was immediately drawn to Selenitsch’s project called Australian Crawl. In it, he imagined an alternative art history in which Piet Mondrian decided to move to Australia rather than New York. I will conclude this essay with some of the notes that accompanied this astonishing work, and the thought that this, and similar projects by a range of artists around the world, represent ‘the next step’ in the growth of genre-switching Superfiction projects, that also takes ‘plot’ into the realm of fiction:

Imagine the following alternative art history scenario: Piet Mondrian is an obsessive swimmer instead of a jazz tragic. Based on his passion, Piet flees Europe during WW2 to relocate to Australia rather than to New York. He gets a studio in Bondi, naturally, and to make ends meet he teaches swimming lessons on the weekends… While his art is embraced by Sydney’s underground contemporary art scene, he is ignored by the nation’s art establishment who believe that his artwork is a hoax;

Nick Selenitsch in his studio, November 2022.

Photo: Savage Garden

Nick Selenitsch, /, (f), Synthetic polymer paint on foam kickboard,

36 x 25 x 3 cm, 2022

Photo: the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne

all Modern Art, they believe, is a hoax. Instead, the only official honour he receives in Australia is to be placed on the honour board of the Bondi Surf Bathers’ Life Saving Club, for ‘services to the local community.’ Decades later, long after his death and, coincidentally, around the same time as his Bondi studio is being demolished for luxury apartments, Mondrian receives a posthumous retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.41