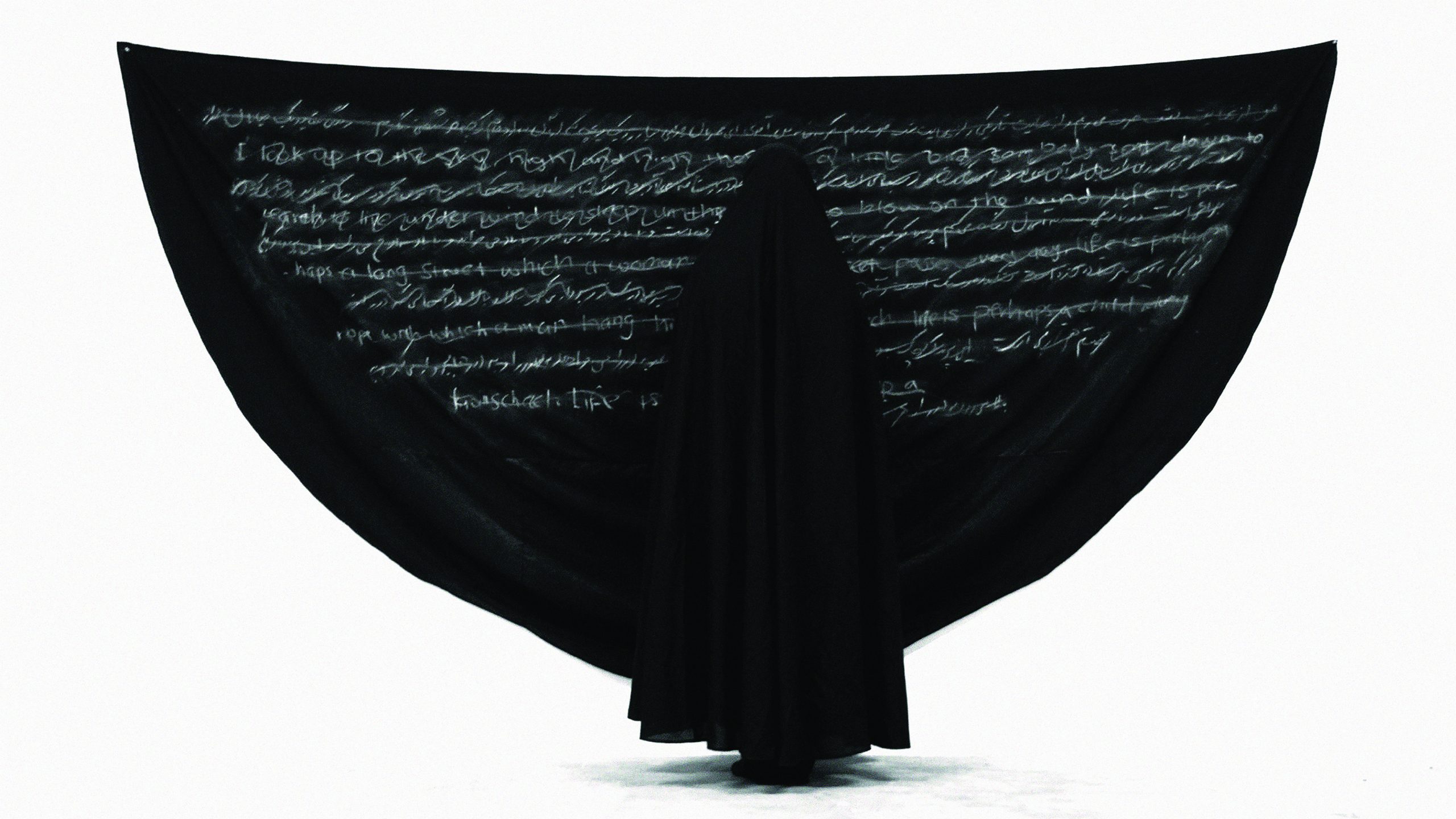

Liberation (Restless), 2010

Giclée print on Hahnemuhle German etching paper

The following article is divided into two parts. The first will address the work of the Iranian-Australian artist Nasim Nasr who has been working from 2009 to the present. The second part of the article looks at the theory and development of modern European playgrounds from the 1930s on.

The reason for bringing these two subjects together is that Nasr’s work could be viewed as analogous to a game of social chess, especially given the artist’s experience of living and working in a cross-cultural context. This analogy can be understood in the context of social play, wherein the chess board becomes the playground on which each move has a strategic significance and impact on the outcome of the game. However, an appreciation of Nasr’s work and of playgrounds shows that this perceived analogy is both constrictive and misleading. Playgrounds require a different set of skills from those required for chess and offer a creative potential insofar as one can shift or break the rules of the game. As Richard Bailey has summarised in his study of the literature around children’s play:

The image of chess is really insufficient to capture the intricacies of normal childhood social exchange. Firstly, not all social interactions are competitive, and even co-operative behaviour requires considerable mindreading skills. Secondly, for most of us, chess requires intense thought and effort, whilst children’s social exchange is carried out with consummate ease and intuition. Unlike chess players, children can adapt or break the rules; they can change identities—pawns suddenly become knights or kings— and they can even switch sides.1

Ashkdān (Tearpots) 2, 2022

Blown glass group of seven, 95 cm (H) x 65 cm (W) x 65 cm (D)

Signed with monogram on base

Measure of Love (Ashkdān), 2022

Archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photorag Baryta

Part One: Nasim Nasr

Over the past year Nasim Nasr has been making a series of sculptural objects entitled Measure of Love (Ashkdān). They are a contemporary interpretation of an Iranian glassware tradition, the ‘ashkdān’or glass ‘tear-pots.’ The glass bottles have a distinct tear-shaped opening at the top which flows into a thin curvilinear neck, before expanding into a larger round body at the base. In this regard, they have a visual resemblance to the curved and attenuated neck of a swan.

The tradition of the ashkdān began under the reign of Shah Abbas I (1587-1629), notably in both the Shiraz (south-central Iran) and Isfahan (central Iran) provinces. Inspired initially by 16th-century Venetian glassware imported into the Muslim world, ashkdān were made by the women during the Qajar dynasty (1794-1925) in the 17th –18th centuries in Iran.2

Folklore has it that ashkdān were used as both rose water sprinklers and to collect the tears of wives separated from their husbands, often in times of war—hence the Persian appellation ashkdān, ‘container for tears.’ The women invented these tear-pots to measure and contain their love, pain and emotions during these separations, of being alone and in isolation, while their family members were absent. Nasr made a series of these tear-bottles as she wanted to address ‘the measure of love’ in contemporary times. As Nasr recently noted, “how can one measure the emotions and love during separation in pandemic time and battle [sic].”3

This work recalls one of Nasr’s earliest works, Unveiling the Veil, 2010, a video that captures the artist wiping eyeliner off with her tears, as if to gain better or clearer sight. Seen in the context of Islamic culture, this gesture suggests a greater symbolic meaning. It is one of her first videos and in Nasr’s words, the work “explores repressive conventions relating to gender, especially the chador, in a poetic and hypnotic way…(It) comprises close-up black-and-white footage of her rubbing her eyes so they weep, making her mascara run. This emotionally intense gesture is filled with sorrow and remorse.”4 Her eyes filled with tears express her emotions about the limitation and lack of freedom; the tears a result of separation from her past life in Iran. It is a gesture that poignantly captures that the burden of difference that lies in the hands of ‘the other’, to resolve themselves by their own disavowal. As Muslim women, they are reduced to the point where they feel that there is noone to blame but themselves.

Born in Tehran in 1984, Nasr received a BA in Graphic Design at the Tehran University of Art in February 2008. From 2006, she had begun to participate in exhibitions with drawings and paintings of female nudes, a subject not allowed in Iran. This was to be expected as it was difficult for women in Iran, as in Afghanistan, to have control over their own rights. Nasim decided to leave and by February 2009, moved to Australia. There she began her studies for a Masters of Visual Arts at the University of Newcastle in the state of New South Wales. By August, Nasim had moved to Adelaide in South Australia to increase her chances of gaining citizenship as there was less demand in comparison with the Eastern states.5

Once settled, Nasr continued her studies at the University of South Australia.

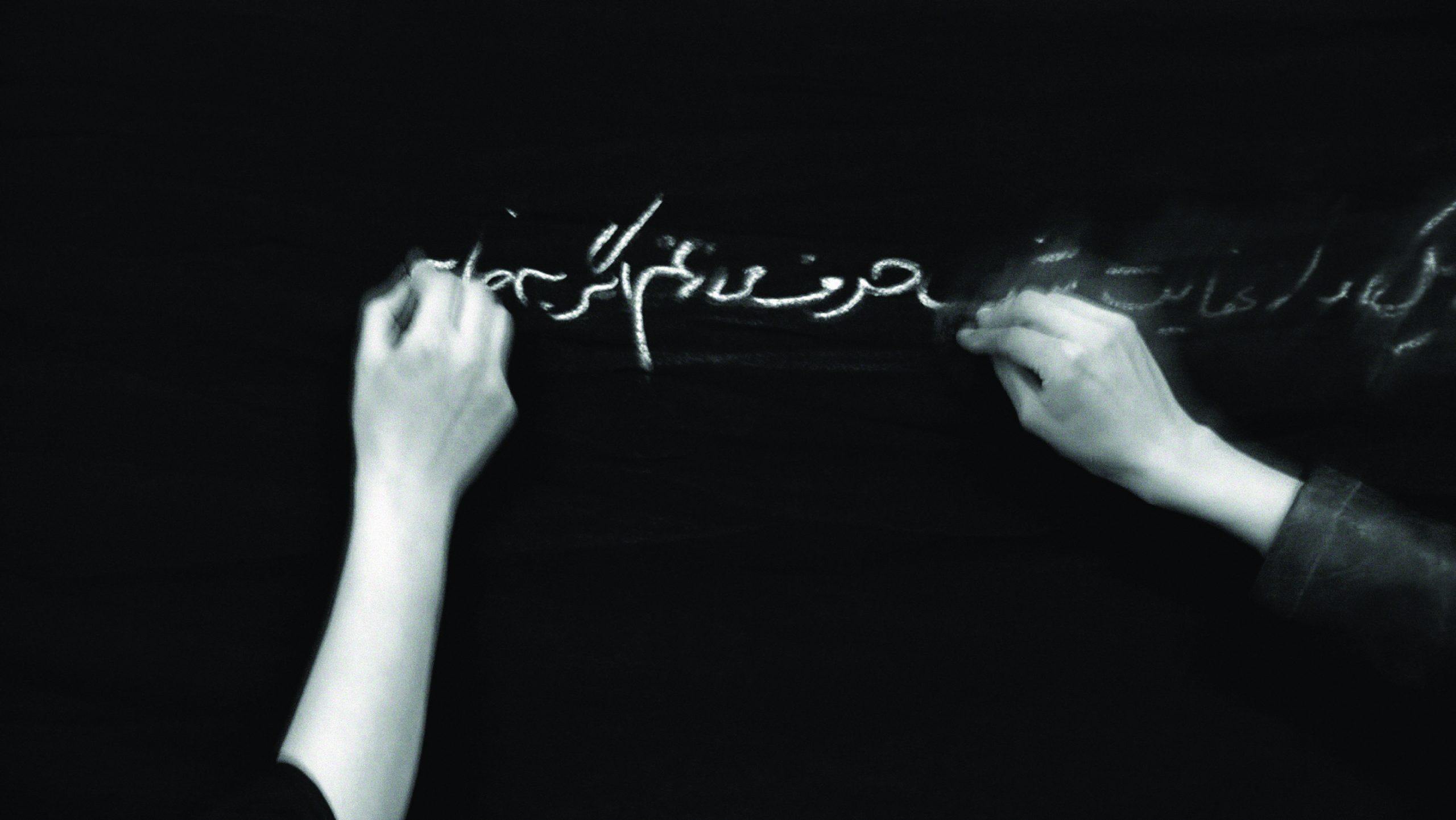

Erasure, 2010

video stills, left and right screens,

Two-channel HD video monochrome; sound

Early on in Adelaide, Nasr was taken to visit the nearby Maslin Beach. It was a nudist beach and she saw public notices at its entrance stating people were not allowed to enter wearing clothes. It was initially a shock to her, contrasting radically with the rules governing women and men in her homeland of Iran. Recognising the stark contrast between her Iranian past and the present—in particular, between the censored and veiled female form in Iran and the present openness in her newly adopted country, Australia—Nasr’s art practice took a new direction. She began to shift towards photography and video and had her first Australian exhibition at Format Gallery (a government-funded experimental art space) held from December 2009 to February 2010. She was still a student. Her exhibition Liberation was a series of photographs depicting the artist wearing a black chador taken at Maslin Beach.6 As Nasr explains: “It (was) a contrast between what I used to do back in Iran and what I am now in Australia. I was looking at how it might work to shift from nude drawing in a religiously restrictive country to covered women in this new free land—at Maslin Beach, the nude beach. I wanted it to be an ironic visual presentation.”7 Moreover, a study of Nasim’s practice serves as a catalyst towards exploring the complexity of issues facing many diasporic women from the Middle East.

In 2010, Nasr made a two-channel video, Erasure.8 It shows a woman dressed in a black chador, writing a poem in Farsi (written right to left) with white chalk on a black chador draped on a wall. Part of the poem reads in English as follows:

Life perhaps is that cloistered moment

When my gaze comes to ruin in your pupils

Wherein there lies a feeling

Which I shall blend

With the light’s impression

And the night’s perception.

In a room the size of loneliness

My heart the size of love

I will plant my hands in the garden, I will grow, I know I know,

I know…

The writing of this poem in Farsi on a chador is closely followed by the artist’s hand erasing the written text. This is closely followed by a text (presumably a translation of the original) being written in English (from left to right), overlaying the partially erased Farsi text. A final movement then follows with the woman’s hand who had initially written the poem in Farsi, trying unsuccessfully to erase the English. Coming to the end of a line of what has been written, the woman’s hand then works back over the partially erased English text. Running an erratic line through, she tries unsuccessfully to make illegible what has been written.9 The two texts in Farsi and in English are contesting each other. Full erasure never succeeds—there is always the trace of the original, however much we succeed in its overwriting and suppression.

Unveiling the Veil, 2011

video stills,

Single-channel HD video monochrome; no sound

The original text of Erasure is a famous Persian poem called Rebirth or Another Birth by Forugh Farrokhzad (1935-1967), an Iranian poet and filmmaker who had difficulties publishing her poems in Iran during her short life. Nasim recalls that she thought the poem could work perfectly for what she trying to express: “I used this poem as I always felt so connected to its words and meaning and as I was dealing with the idea of erasing memories of my past in Australia dealing with a new language.”10 In 2012, Nasr presented Women in Shadow 1, a performance through which she addressed the subject of veiling/unveiling as symbolic of issues surrounding the discrimination against Muslim women. In the performance, professional models wearing the chador with heavy makeup and high heels, parade along a catwalk over the 45 minutes of its duration.

Women in Shadow II, 2018

performance stills,

Archival pigment print on Hahnemühle Photorag Baryta

The subject of invisibility/visibility is played out as the veil dissolves into the shadows. This invokes the socio-cultural invisibility of women in Islamic countries but, equally, the overexposed, commodified image of women in the West.11 This is not simply a dichotomy of the veiled or unveiled, containment or freedom, East vs. West. Rather, either way, both terms are mobilised, as if held in an oscillating counter-balance, anticipating the essential dialectic that drives Nasr’s work. Nasr’s work represents an unsettling encounter with difference—a difference that destabilises Western norms of the body as free only when it reveals itself. This institutes a politics of othering.12 Looking back, the significance of the work is its anticipation that women’s struggle for freedom from imposed constraints of identity is far from over.

The veil in Women in Shadow 1 becomes a flashpoint for the relationship between the body and knowledge, the politics of freedom grounded in the body. But the impulse to unveil is more than a desire to free the Muslim woman. Behind the desire to release (Muslim) women’s bodies from the veil is the intolerable possibility of limits. As Talal Asad contends in Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity, an aggressive re-centring of discourses of the west occurred following the events on the 11 September 2001.13 This led to a renewed commitment to the values of democracy and freedom, terms believed to be exclusively affiliated with a western liberal tradition.

The preoccupation with the veiled woman is a western defense that preserves neither the object of orientalism nor the difference embodied in women’s bodies. Rather inversely, it is based and insists on the idea of a universal free subject that privileges the west. What lies at the heart of the politics of othering, in this case the fantasy of saving the Muslim woman, is recast here as the west’s desire to save itself. The veiled and unveiled activates an imagining—the possibility and impossibility of a stable “west” and the epistemic conditions of freedom, truth and knowledge which sustain it.

For Nasim Nasr, born and raised in Iran and living in Australia for the past 14 years, issues around the discrimination of gender and continuing anxiety around identity have been points of continuing focus throughout her work.14 Her work has explored, as the editorial of this journal ISSUE states, the “contested freedoms in the determination of space, what is contained within a space and who should be in this space.”15 These issues persist today, especially for women, in different ways and forms, not only within Islamic countries but globally.

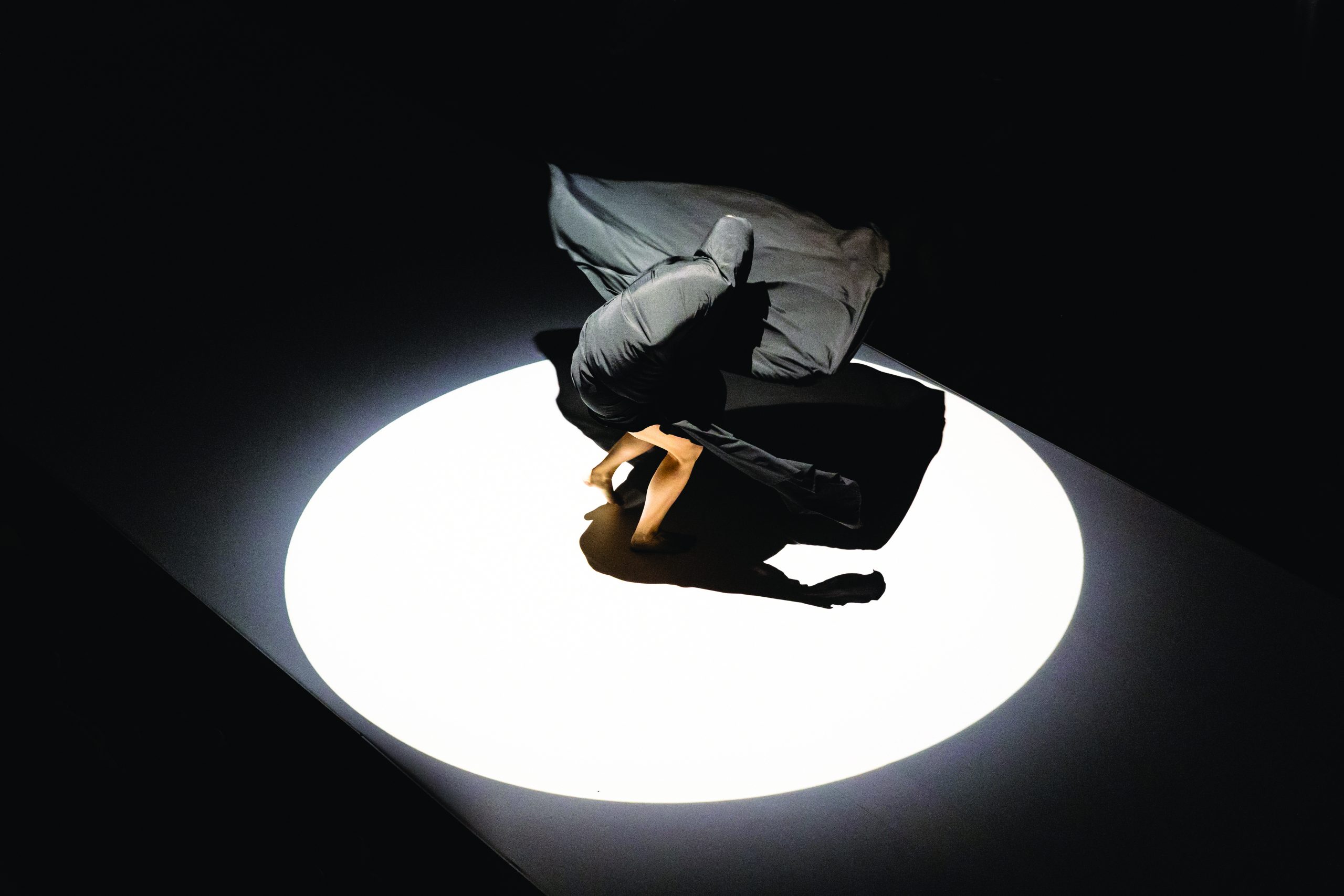

Recently, the new work of Nasr extends while reflecting back on her earlier work. One of these new works is Impulse, composed of a dance-work collaboration between one male and one female each moving with and struggling against a black chador and a white chador. Like pieces on a chess board, it suggests the contrast and struggle between Nasr’s past and present.

This work also relates to her Liberation series of 2010 and back to her performance Women in Shadow 1 of 2012. The potential liberation and tension of the moving figures in relation to the chador, symbolic of identity formation, captures both the necessary and possible liberation of the figure. The dance builds, intensifying with each movement, as if capturing and exposing the layers of emotion to an uncontrollable point where they might fragment or evaporate. The movement of the figure offers a glimmer of hope that it will free itself of societal constraints defying the rules of the game and, in that moment, both define itself and be liberated.

Part Two: Playgrounds

From the turn of the last century until the 1980s, playgrounds in the Western world reflected the changing status of children within society and its impact on urban planning, architecture and art. Playgrounds were developed as defined and controlled spaces for children. Moreover, the element of play belongs mostly to an aesthetic impulse that corresponds with the impulse to create an orderly form which animates play. The connection between playgrounds and art is characterised by Gabriela Burkhalter when she writes:

“The history of play sculpture and playgrounds in general can be understood as yet another overlooked chapter of modernism. Connecting play, art, education and public space, it finds itself at the centre of some of the 20th century’s most pressing issues. Playgrounds became lively, interactive and imaginative public spaces.”16 The first playgrounds were built at the end of the 19th century, when child labour had begun to be outlawed and children’s leisure and security became a concern. The emergence of the welfare state brought children’s creativity into focus. Play activities were designed for public spaces and with children’s needs in mind.

During the inter-war period, the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga (1872-1945) wrote Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture in which he proposed that all play moves and has its being within a playground marked off beforehand either materially or imaginatively.17 Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the `consecrated place’ cannot be formally distinguished from the playground. Inside the playground a special order reigns absolute. There is an affinity between play and order. It brings a limited, if temporary, perfection into an imperfect and unpredictable world or haphazard way of daily life.

Huizinga also argues that there is a fusion of play and poetry. He suggests that the function of the poet is fixed in the play-sphere where it was born. Poesis is a play-function and proceeds within the playground of the mind, in a world of its own which the mind has created for it. It lies beyond seriousness, in the region of dream, enchantment, ecstasy and laughter. It is bound by rules that must be consciously entered into. “It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner.”18 There things have a very different physiognomy from the one they wear in ‘ordinary life’ and are bound by ties other than those of logic and causality. The capacity of poetry and play is its potential for unlimited transformation or, in a Nietzschean sense, the way that being is undermined by becoming. Play contains an intrinsic paradox that teases us simultaneously with seriousness and playfulness, flow and structure, liberty and order. Such is its undoing, for according to Huizinga, as soon as we enter the play-mood, respect for the rules of play, for its order and form, must be zealously maintained or else we risk being brutally thrust from its sphere.

Roger Caillois (1913-1978), one of the founders of the College of Sociology in Paris along with Georges Bataille in the 1930’s, would later dispute Huizinga’s conception of play in his book Man, Play and Games.19 Caillois redefined play as an activity connected with no material interest—no profit can be gained by it. It proceeds within its own proper boundaries of time and space according to fixed rules and in an orderly manner. It promotes the formation of social groupings which tend to surround themselves with secrecy and to stress their difference from the common world by disguise or other means. Caillois argues that play and games give us an appreciation of the patterns and themes of a culture. An art work, installation or performance can tease out material differences and commonalities as symbolic of social life and exchange.

For a long time, artists and the avant-garde have embraced playgrounds as a sphere of experimentation and place of freedom for children. With this potential, the playground became a laboratory of experimentation, a defined and yet liberating ground on which contestation and freedom to break the boundaries has always been a latent potential.

Artists in the early days of the Soviet Union in the 1920s engaged closely with all spheres of education and the arts, most especially under the short-lived guidance of Anatoly Lunacharsky, at one time the People’s Commissariat for Education (Narkompros). By the late 1920s such foresight disappeared from government cultural policy and by the early 1930s, the avant-garde was closed down and eradicated by Stalin’s regime. As with elsewhere in Eastern Europe, playgrounds became part of the State apparatus. One such case was the mass distribution of climbing frame equipment on the playground, part of which were rocket-style climbing frames in the 1950s. At the time, a large number of children dreamed of being astronauts. The astronauts Yuri Gagarin and Valentina Tereshkova became heroes and role models for millions of children and adolescents and their portraits were a common attribute in every school. Playgrounds became a symbol of State ideological propaganda and helped in the construction of an image of a strong communist party. After perestroika and the complete collapse of communism by the beginning of the 1990s, playgrounds began to change again and slowly were more liberated from ideological determinism.

In Western Europe, the first adventure playground opened in Denmark in 1943, and between the 1950s and 1970s other activist initiatives and methods to encourage children’s play became widespread. In the late 1940s, the artist and architect, Constant Nieuwenhuys (1920-2005), emphasised collective creativity. He was at the time, a member of CoBrA, a movement which he had co-founded with Danish, Belgian and Dutch dissident surrealists. They advocated free and spontaneous art and, together with Christian Dotremont, Eph Noiret, Corneille, Karel Appel and Asger Jorn, published La cause était entendue (The cause was heard) in 1948. After his CoBrA years, Constant became interested in the influence of the built-up environment on human activity; his abstract constructions from those years can be seen as architectural or urban planning studies for the spatial application of colour. He called for a movement towards nomadism and the generalisation of playful behaviour.

In the early 1950’s, Constant began collaboration with the group Team X, most notably his fellow Dutchman Aldo vVan Eyck (1918-1999). Born in Driebergen (the Netherlands), Van Eyck grew up in London between 1919 and 1935 and then studied architecture at the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich from 1938 to 1942. During these years, he became acquainted with the international avant-garde and remained in Zurich until the war ended. In 1946, Van Eyck moved to Amsterdam and began working for the urban development division of the city’s Department of Public Works under Cornelis van Eesteren and Jakoba H. Mulder.

Van Eesteren (1897-1988) was chief architect of Amsterdam’s Urban Development Section since 1929, after having trained in Amsterdam and Rotterdam. During this time, he was influenced by the Bauhaus and by Van Doesburg and became involved in the Dutch De Stijl movement and their theory of neoplasticism. Following his training, he concentrated on urban planning at the Institut d’urbanisme de l’université de Paris (IUUP) at the Sorbonne in Paris.

From 1930 until 1947, Van Eesteren was chairman of the Congress International d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM). In 1933 he was asked to prepare a number of analytical studies of cities for the main meeting of CIAM that was planned for Moscow. The concept for these studies was the ‘Functional City,’ a concept that had come to dominate CIAM thinking after their third conference, held in Brussels in 1930. Le Corbusier had exhibited his ideas for the ideal city, the Ville Contemporaine in the 1920s, and during the early 1930s, began work on the Ville Radieuse (Radiant City) as a blueprint of social reform. The Ville Radieuse was a linear city based upon the abstract shape of the human body with head, spine, arms and legs. The design maintained the idea of highrise housing blocks, free circulation and abundant green spaces proposed in his earlier work. These were based in part on urban studies undertaken by CIAM in the 1930s.

At a meeting in Zurich in 1931, CIAM members—Le Corbusier, Walter Gropius, Siegfried Giedion, Rudolf Steiger and Werner M. Moser—discussed with Van Eesteren the importance of solar orientation in governing the directional positioning of low-cost housing on a given site. In CIAM’s Athens Charter of 1933, Le Corbusier opted for a massive rebuilding of cities in which the functions of labour, living, and leisure are spatially segregated, and street life was reduced to traffic flows. Van Eesteren embraced a strict functional separation of housing, work, traffic, leisure and nature, and envisaged highrise blocks and huge traffic arteries to replace traditional cities.

In postwar Amsterdam, Van Eesteren together with the engineer Theodor Karel Van Lohuizen developed the the city’s zoning plans—the Amsterdam Expansion Plan—that would predict overall future development in the city, including population development, the use of land, buildings and transport. They relied upon the rational methods being promoted by CIAM at that time, which sought to use statistical information for designing zone uses rather than designing them in any detail. The town planning section of the city of Amsterdam wanted to have a playground in each neighbourhood of the city of which parts had been destroyed during the war. However, although the importance of leisure and children’s play was recognised by Van Eesteren and members of CIAM, they imagined leisure in ‘idealised settings,’ away from the houses of the children.

Meanwhile, Constant had begun to focus on construction and experimented with sculpture, inspired by neoplasticism and then neo-Constructivism. From 1954 until 1956, Constant collaborated with Nicolas Schöffer, creating several spatio-dynamic projects, and this led to an introduction to the Espace group, of which Schöffer was a member, founded (in 1951) by André Bloc and Felix Del Marle. While working as an engineer Bloc had become interested in architecture. Through magazines he founded and led, notably L’Architecture d’aujourd’hui and Art d’aujourd’hui, he was an ardent supporter of a renewal of the relationship between art and architecture in reaction to Le Corbusier. While Constant participated with Dutch members in meetings of CIAM, he was personally drawn to the Espace group who advocated a new synthesis of the arts in France. They viewed architecture and art (painting and sculpture) as a social phenomenon and integrated constructivism and Neoplasticism in city planning and the social atmosphere.20

In 1956, Constant joined the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus, which Asger Jorn had founded as a reaction against the International Style of Le Corbusier. That same year, he abandoned painting to exclusively dedicate himself for 18 years to New Babylon, a radical illustration of “unitary urbanism” by Guy de Debord. He also participated in the founding of the Situationist International in 1957, who saw play as essential to the ontological freedom of the human being. Expanding on Huizinga’s concept of play, Constant along with other leading SI members, notably Guy de Debord and Asger Jorn, believed that the ability to play had been lost—a phenomenon that could be directly attributed to a passivity in the face of the spectacle. To redress this, they proposed that homo ludens become itself a “way of life” that could respond to this human need for play, as well as “for adventure, for mobility, as well as the conditions that facilitate the free creation of his own life.”21 Constant argued that, in opposition to a postwar commodity culture, play should be thought of as a guiding ideal. He wrote that the liberation of man’s ludic potential is an essential part of the liberation of the social being.22 Similarly, Van Eyck viewed architecture very differently from Van Eesteren and CIAM, believing it should aim at creating places that fostered dialogue and stimulated community life in which children take part. At that time the contrived playgrounds were generally isolated places. Van Eyck’s playgrounds were never fenced. Contrary to the program of CIAM that proposed a massive rebuilding of the city, Van Eyck used existing and ignored spots in the neighbourhoods of the cities to create places for social gathering and children’s play. He developed an architecture of the in-between realm in which there were no sharp boundaries that separated the playground from the rest of the city.23

The significance of Van Eyck extends beyond his contribution to Dutch culture to that of the architectural planning of cities, especially in postwar Europe, in which he advocated dialogue and community. This was exceptional in the 1950s and 1960s and encouraged by the citizens of Amsterdam, who had explicitly asked for a playground in their neighbourhood, Van Eyck transformed over 700 public playgrounds designs located in parks, squares, and derelict sites in Holland over the course of the next 30 years.24

Conclusion

As I have explored, playgrounds may be seen as being somewhat analogous to a chessboard, but they are not. The latter is over-determined by the rules of the game while the former, if seen within a progressive tradition, are quite the opposite.

If chess is analogous to Nasr’s work, it is only in recognising the strategic significance and the potential impact of each move on the outcome of the game. That is chess, like social customs, has strict rules and conventions. However, this where the analogy ends. Rather, we see in Nasr’s work that as a woman and a Muslim, she is faced with social conventions both in the Middle East and in the West, in particular, Australia. That is, women have a place but no position, nor voice. They are virtually invisible. What Nasr seeks is to play with these social conventions, if only then to break them. Her art seeks to deconstruct the rules of the game, to contest or break with these rules, offering a perspective from her point of view as both a woman and a Muslim.

Playgrounds, on the other hand, embody the ludic potential of people, a potential that was seen in postwar Europe as liberating man from the growing oppression of a commodity-driven culture. The collaboration between Constant and Van Eyck brought theory and practice together and the progressive history of postwar reconstruction in Amsterdam is indebted to their work.

The practice of Nasr and of Constant and Van Eyck together challenge any analogy between chess and playgrounds. Their work deconstructs the dominant social conventions and world of unfreedom where one can only play according to the rules of the game. They recognised that while playgrounds are spaces of social interaction, these spaces also embody a creative potential latent within social exchange. This creative potential is why playgrounds can be defined as laboratories of experimentation and places of freedom.