This essay is based more on my experiences as an artist experimenting with producing artworks and observing the development of Indonesian art, than on theories or theoretical explanations of creation. My experiment was based on a sense of play, trial and error, and ‘madness,’ practised in the context of resistance to the establishment, and as such, strongly opposed by established artists at the time.

As an art student, I did not have strong drawing skills. However, I did not give up because I believe art is not based only on good craftsmanship. I believe that ideas are quite important in the creation of art, and they do not come from drawing skills.

According to my seniors and teachers, an artist’s hand is similar to a seismograph needle1; it can show the vibration of the artist’s emotions and feelings while creating works of art. An artist’s hand creates strokes that authentically represent the artist’s emotions, feelings, and soul.

What about themes, colour schemes, and critical approaches to presenting the painted objects? Is it all based solely on feelings? Is it true that an artist’s intelligence and reason are irrelevant? What about ideologies, concepts, and mediums?

It is my argument that the idea of the artist’s hand as a seismograph does not exclude the need for the artist’s intellect. The artist’s hand as a seismograph manifests the intellect, feelings, emotions, techniques and the whole being of the artist’s experience and life authentically manifested on the canvas. Teachers, senior artists and other students consider that reason and critical analysis are not part of creation but part of criticism or writing. In my opinion, I do believe that intellect, feelings, emotions, techniques and the whole being of the artist’s experience and life are authentically part of creation. Ultimately, what we should question is why the artist’s hand is privileged here in manifesting the ‘visible soul’, a question raised by artists from the The Indonesian New Art Movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, or GSRB).

We, from the New Art Movement, see that the teachings about the soul appear to be represented by the hands that make art, clearly setting aside ideas and concepts in the creation of works of art. Senior artists consider that emotions and feelings are more important than thoughts, ideas and concepts. In hindsight, only after we understood the ideology of modernism and postmodernism do we understand that prioritising emotions, feelings, and expressions is a representation of the ideology of modernism. However, the seniors did not actually understand the ideology of modernism correctly.

These questions compelled me to reconsider the place of reason in the understanding that humans are primarily composed of both reason and feelings. Reason encourages a critical approach to seeing and placing creation in its social context. Emotions and feelings do not have to be expressed through strokes only but can be noticeable through colour selection, composition, a playful creation process, and other elements.

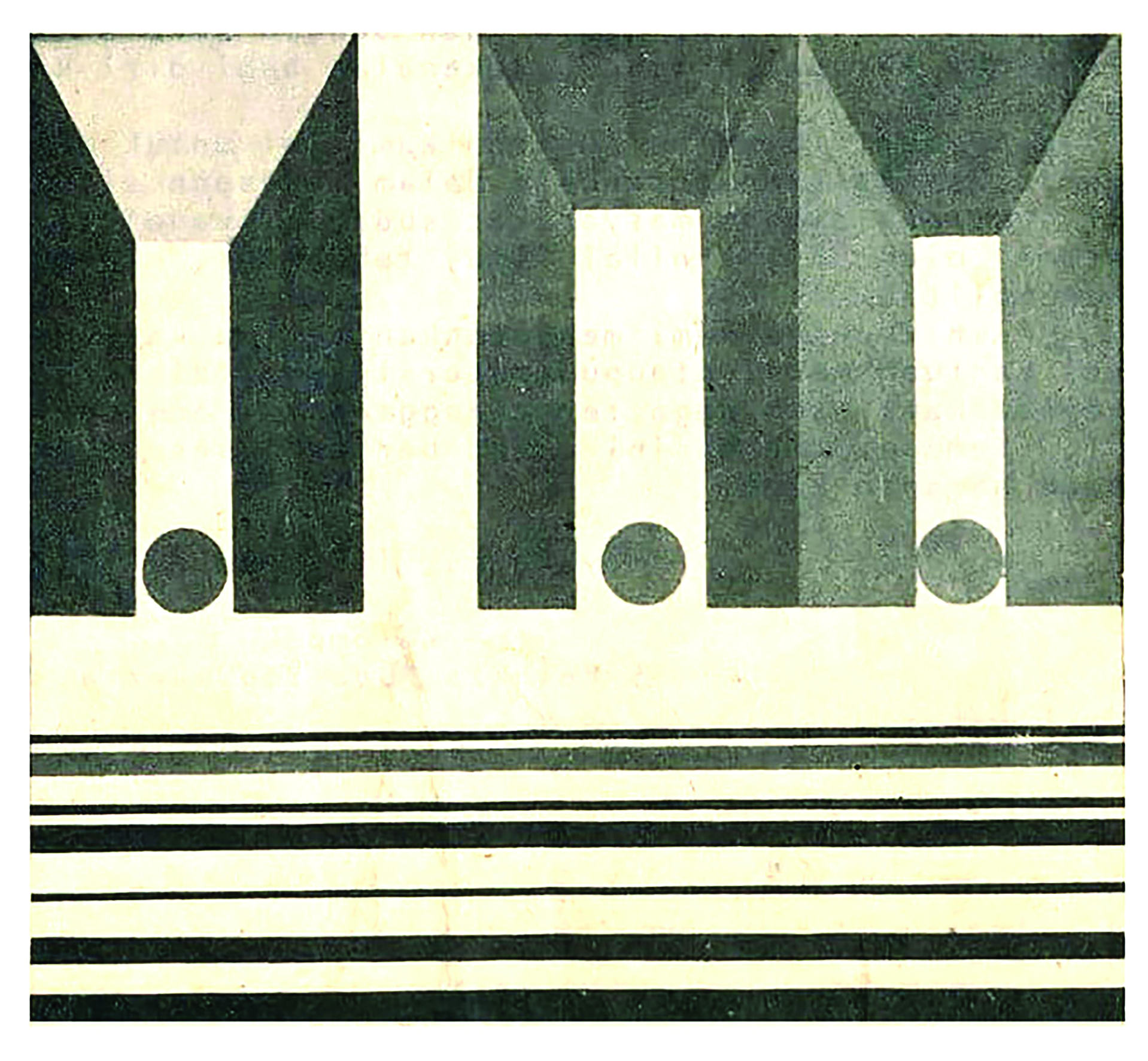

I was required to attend painting classes in 1973. I used a ruler and a compass to paint flat colours. I was inspired to paint by the concept of space and the play of optical effects. I did not use any texture or brushstroke in my paintings. Fortunately, the lecturer who taught the painting class, Fadjar Sidik, was an abstract painter. He liked and approved of my painting style. Fadjar Sidik described my painting style as ‘geometric’.

In FX Harsono: A Monograph (FX Harsono: sebuah monografi), Hendro Wiyanto, an art critic, curator and writer, wrote about my work: “The canvasses’ surfaces are divided with a ruler and measured with a compass, then the faces are evenly coloured, and the compositions are orderly and neatly designed, sometimes implying a double perspective on space. The paintings appear playful and depart from the mimetic art tradition of creating the illusion of depth of space. The flat surface has evolved into an independent subject, rather than merely a backdrop for presenting objects or representing specific images.”2

At the time, teachers and seniors, who still adhered to modernist ideologies that highly valued craftsmanship, dominated educational institutions. Artworks must be original because artists were viewed as geniuses who should not be interfered with. The work produced should have an aesthetic aura because the artist’s soul is considered to be a crucial component of creation. In contrast, I believe that ideas, concepts, and playful ways of creating art are valid as creation ideologies; this was not in line with the teachers’ ideology, who were also senior artists. As a result, they rejected my concept.

Dimensi 3 Bulatan Dalam Ruang dan Gerak Garis is related to the primacy of ideas and playful ways of creating; it serves as an entry point to discuss ideas of playfulness and concept. It shows the process of creation from my rejecting the statement “the hand as a seismograph needle,” and developing the idea through several years of experimentation that led to the work, Space 74 no. 4 (Ruang 74 no. 4).

Indonesian Identity

In 1972, a debate erupted in Indonesia’s largest newspaper, KOMPAS, between Sindoesoedarsono Soedjojono, a painter, and Oesman Effendi, a painter and writer. Oesman Effendi declared there was no such thing as Indonesian fine art whereas Soedjojono claimed that Indonesian identity was present in the populist spirit that inspired the creation of the painting.

Oesman Effendi’s criticism stemmed from his observation that all media, painting creation processes, and theories used to critique art originate from the West. We found this polemic to be a hot topic of debate. To us students, this topic became a pivotal question for us to think about the identity of art in the context of Indonesian culture.

Dimensi 3 Bulatan Dalam Ruang dan Gerak Garis

(Dimensions of 3 Circles in Space and Line Motion), 1972

oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm.

Photo: Courtesy of FX Harsono

“How can art present an Indonesian identity?” was the starting point for our experiments. We also examined the medium, the artistic process, and the theme. The educational framework and resources we used came from the institutions where we were studying.

The education system was based on a very limited discourse on European modern art and the lecturer’s experience as an autodidact artist. There was no room for exploration or experimentation. What the teachers said was absolute truth that was inviolable. Drawing skills and craftsmanship techniques were highly emphasised. Theories were subordinated to the practice of creation. The importance of drawing skills and craftsmanship techniques is foregrounded. Practice is prioritised over theory.

Teaching materials derived from European and American modern art theories were not taught thoroughly, resulting in a superficial understanding of them. As students, we were dissatisfied because we realised we were not receiving a proper and good education to be artists.

The dissatisfaction and the thirst for finding our Indonesian identity drove us—Bonyong Munni Ardhi, Siti Adiyati, Nanik Mirna and myself—to experiment. The spirit of play was essentially a form of resistance to the dominance of Western-style education, which shackled creative freedom. In that freedom, I discovered the ability to think critically about the search for identity, theme selection, and the creative process. The spirit of play and ‘madness’ fosters freedom, which cultivates the courage to break the rules of Western-centred creation.

Moreover, I started to get restless because I felt that the existing forms of work and creative processes were disconnected from social issues. This restlessness prompted me to begin experimenting in the spirit of play. I combined found objects with geometric shapes.

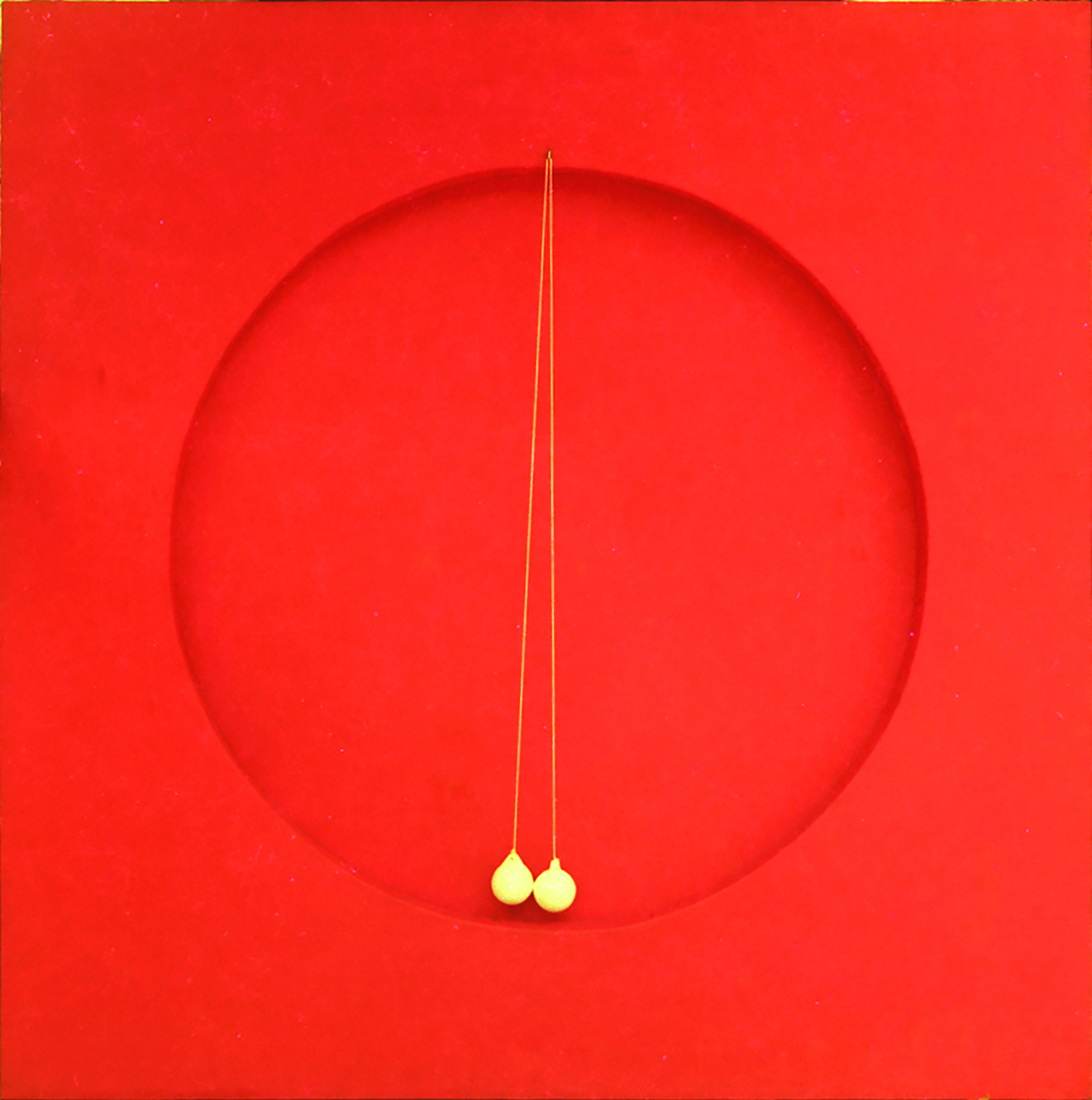

In 1974, I created a piece entitled Space 74 no. 4 (Ruang 74 No. 4), 1974. It was a flat red square canvas 100 x 100 cm with a concave in the centre of an eight-centimetre depth. I placed an object in the centre of the circle, a toy known at the time as Nik-Nok or Clackers. This toy is currently gaining popularity under the names Lato-Lato or Ethek-Ethek.

I also created a smaller work titled Space 74 no.5 (Ruang 74 No. 5), 1974. It was an 80 x 80 cm canvas divided in two, with the top flat and the bottom wavy, on which I placed a brightly coloured trumpet made of zinc and strings.

Space 74 no. 4 (Ruang 74, No. 4), 1974

acrylic on canvas, crackle toys, 100 x 100 cm.

Photo: Courtesy of FX Harsono.

Both paintings were on display in 1974 at the first (Pameran Besar Seni Lukis Indonesia),Great Exhibition of Indonesian Painting3 organised by the Jakarta Arts Council (Dewan Kesenian Jakarta), which took place at Taman Ismail Marzuki. My works, as well as the work of several other young artists, were presented with a spirit of playfulness and mischievous experimentation. During the award-judging process, our works received frank and harsh criticism from the jury:

“It is an attempt to experiment with what is ‘new’ and ‘strange’, which can only be interpreted as trial and error, a gimmick, or evidence of a scarcity of ideas and creativity.”

Furthermore, it was assumed that originality, as unquestionably essential for artists, means that the artist’s work must be unique, so using found objects was considered a violation of originality.

The debate over how ‘originality’ was defined in the 1970s is worth unpacking further. For example, can originality be located in new ideas, or new ways of using materials in art? Originality remains one of the most fundamental touchstones of Modernism in ‘Western art’ and yet is still relevant today as a criterion for assessing art.

The “soul that appears” is considered to represent the artist’s self and it is there that originality appears. Meanwhile, for the artists of the New Art Movement (GSRB), ideas and concepts are considered as the basis of creation. Originality must be born at the hands of artists. There is a distinction in the meaning of originality between modernist artists and younger artists. Found objects do not represent originality but under the new art, they are presented with and given new meaning. For modernist artists, this method is considered not to reflect originality.

We responded quickly to the criticism and we were backed by several other artists. Then we started a petition stating that artists should be free to experiment in any way they want. The petition became known as Black December because it occurred in December 1974. We distributed the petition and made a flower wreath similar to those given to the deceased, with the words (in Indonesian) “Condolences on the Death of Indonesian Painting” written on it. The wreath was then presented during the presentation of awards to the five selected painters.4

Black December wreath 1974, from young artists.

Photo: Bambang Bujonio / Tempo Magazine

The first exhibition of New Art Movement, 1975, at Taman Ismail Marzuki. Photo: Sri Atmo, 1975, Courtesy of FX Harsono

New Art Movement (Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, or GSRB)

The jury immediately responded in anger. Some of the jury members and awardees were from our campus, STSRI ‘ASRI’.5 Following the exhibition, our teachers summoned us and put us on ‘trial’. We were kicked off campus because our actions were seen as political activism. During the New Order era, students and citizens were prohibited from engaging in any political activity. This prohibition was known as “depoliticisation”.

The dismissal of four STSRI ‘ASRI’ students, combined with the Black December statement, prompted us—six “ASRI” students from Yogyakarta, four young artists from the ITB (Bandung Institute of Technology), and one young artist from Jakarta—to form the New Art Movement (GSRB). In August 1975, the GSRB’s eleven members held our first exhibition at Taman Ismail Marzuki in Jakarta. Installations, found objects, and non-lyrical two-dimensional works depicting everyday objects were among the works inspired by the concepts of play and experimentation that we displayed.

The GSRB exhibition in 1975 drew harsh criticism from critics. They could not identify the works using their modern art references. They claimed that the artworks in the exhibition were vandalism, pornographic, or disrespectful of Indonesian culture. We did, however, have the support of young critics. As a result, a debate erupted in the media at the time.

We did not know what to call our creations, so we just called them “new art.” The process of creation and the forms of our works, according to Sanento Yuliman, a lecturer and art critic based in Bandung, were indeed novel and distinct from previous artists. “So far, our paintings and sculptures have only provided a poetic sense,” Sanento Yuliman wrote, “however, the Indonesian New Art Exhibition ‘75 clearly illustrated a trend that went beyond this… they are against the surreal, magical experience of art; they offer concrete objects.”

By “concrete objects” Yuliman refers to “found objects”:

Some of the artists here ‘play’ with the feeling of concreteness, mixing it with other ‘conventional’ elements as if to surprise us with the concreteness and make it more striking…The bookshelf in Hardi’s painting, for example, or the letterbox in Munni Ardhi’s work are both concrete, as are other works by Harsono such as a plastic gun, a plastic flower in a plastic bag…6

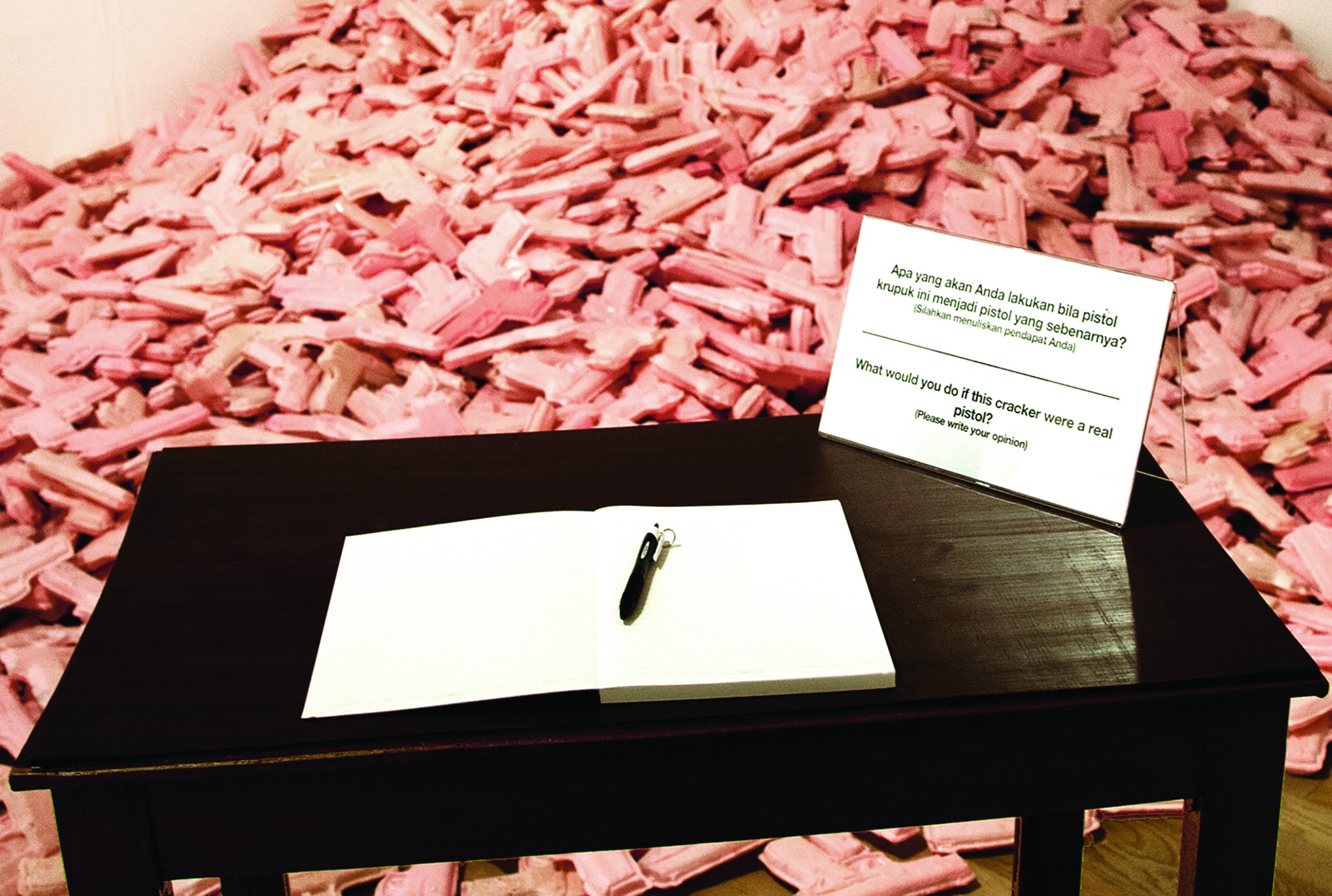

This playful spirit, it turns out, has created a new form of art and a new space of appreciation that is close to the audience. It offers a one-of-a-kind experience in which the audience can interact with the works of the artists. Cracker Pistol, or “What would you do if this cracker pistol turned into a real pistol?” is one of my audience-engaged works. The piece encourages audiences to write down their thoughts as they mull over should the pistol cracker transform into a real gun. This piece is part of a series on anti-militarism.

For this work, I bought two sacks of crackers (biscuits) from a cracker vendor. The crackers were shaped like pink pistols. I piled the crackers on the floor. In front of the cracker pile, a table and chair were set up. A book and a pen sat on the table. On the cover of the book were the words: “What would you do if this cracker pistol turned into a real pistol?” The audience was encouraged to write down their responses to this question. This was a brave act considering the event took place in 1977 when the Soeharto regime7 was extremely repressive and backed by the military. The military’s role in the Soeharto regime was criticised in the majority of audience responses.

I incorporate text into my works when there is a strong need for play. The aim of ‘play’ is to deconstruct creation norms that I consider conservative and out-of-date. It also presents criticism in an indirectly mocking, satirical, or ridiculing manner. Criticism in the spirit of play will produce ambiguity. On the one hand, it criticises; on the other, it appears to be playful and not serious. This is one of the strategies for avoiding government prohibition and arrest.

I also use text within the work with the intention of directing these forms of play. The text is not meant to be provocative, but it may contain slogans, statements, or instructions. In Cracker Pistol, for example, the text reads, “What would you do if this cracker pistol turned into a real pistol?” Another example is The Top 75, which contains the text “The Top 75.” Therefore, I combine visual and written language so that the audience could easily grasp the message. Visual and written language can be presented asynchronously, making them appear contradictory. The goal of presenting it in this manner is to avoid direct and harsh criticism while still providing a clear enough hint of where the work is headed.

Cracker Pistols, 1975 (see facing page). Photo: FX Harsono, 2019.

Cracker Pistols, 1975

installation with wood desk, book, pen, text with digital print on paper, dimensions variable.

Photo: FX Harsono, 2015.

Young artists in Yogyakarta and Bandung began to experiment with unconventional ideas and conceptual works. The consequent deluge of “new art” was unstoppable. The conditions that led to the creation of works such as the New Art Movement persisted. Official educational institutions in Yogyakarta and Bandung eventually added a new course called “Experimentation.”

Contemporary Visual Art

Can it be said that Indonesian contemporary art originated from the New Art Movement (GSRB)? This is a challenging question to answer. We do not explicitly state that our movement involves the creation of works based on postmodern ideology, which is the ideology of contemporary art. Postmodern thought had not yet reached Indonesia, or to be more specific, we were unfamiliar with it. When I began to enter the larger art world in Southeast Asia, Australia, and Japan after the 1990s, I realised that our rejection of seniors in the creative process was a rejection of the principles of creation based on modernist ideology.

We rejected the notion that the artist’s hand acts as a seismograph needle for the artist’s feelings and emotions, that is a manifestation of the artist’s soul. We rejected the idea that the artist is a genius who plays a key role in the creation that is sacrosanct, allowing the work to stand on its own while revealing the artist’s aura. We value ideas and concepts based on our understanding of our surroundings. Western modern art theories are not the only source of truth; rather, artists’ aesthetic values are influenced by their historical and cultural background.

Is this sufficient evidence to claim that the New Art Movement (GSRB) signifies the beginning of Indonesian contemporary art? What is certain is that after the GSRB exhibition, groups with similar artistic tendencies emerged. PIPA, or Kepribadian Apa,8 is one of them, formed by young Yogyakarta artists. There is also Cemeti Art Space, now Cemeti Institute for Art and Society, that was founded in Yogyakarta in 1988 as a contemporary art space.

Because of the rise of social media, serious and meandering discourses have been simplified with popular, light, interesting, and easily accessible texts and features, and the principle of creating by experimenting has become a common basis for creation in Indonesia. It takes a playful spirit to dare to defy all the rules that are perceived to be oppressive in order to attain something simple and interesting out of serious discourse. Given their different cultural backgrounds and the ongoing evolution of modern digital culture, young artists from Generation Z and those associated with the New Art Movement will undoubtedly produce different work.