Initial discussions around International Arts Festivals refer to the Festivals as ‘ports of call’ – points of cultural import and export. Australian composer Jonathan Mills is completing his last term as Artistic Director of the Edinburgh Festival as Singapore theatre director Ong Keng Sen begins his first with the Singapore Festival. Jonathan Mills converses with theatre director and educator Aubrey Mellor about his sources and processes.

Jonathan Mills

In 2004, Ong Keng Sen and I started to think deeply about how Australia and Singapore related to each other. How our histories collided and how those stories might have actually formed a basis of artistic collaboration of a kind of sharing of memory and of empathy that can build us an alternative to ‘those’ history, because that’s what art offers. I also think it is important when thinking about the 50th anniversary of modern Singapore in 2015, to acknowledge one of the things I learnt first of all from Keng Sen in that process of collaboration. We look at Singapore as, I think quite rightly, a very successful multi-cultural society. And indeed it is. It is also as much a place that people arrive in, as they leave from. So much more, Singapore is the result of diaspora, rather than that there is a diaspora. Therefore the ever-present phenomenon of Singaporean ethos is stories from somewhere else finding root and finding locus in Singapore itself. Stories of migration, stories of migration that may be near or far, and stories of shared histories.

And this, I was reminded of, most powerfully on my very first visit to Singapore, when I travelled there with my father, and I was confronted as a ten-year old boy with a growing and very modern metropolis. What my father was able to do was excavate beneath that surface for me. Why is Orchard Road, Orchard Road? You wouldn’t know it today. You know it by its name, not by its powerful vegetation or association. It was a road of orchards, simple as that. So, everywhere one goes in Singapore now, there is a danger – unless you have a guide like Keng Sen or like my father, of forgetting where you really are, and of not understanding of what that history comprises. And I think that would be a great shame. Singapore has developed in remarkable ways, many of them economic, and many of them in terms of the economic prosperity of its citizens; it would be a great shame if that was the cost or at the expense of the broader sense of its history.

Jonathan Mills: photo by Seamus McGarvey

So when you start to think about the 50th anniversary of the founding of Singapore, my mind immediately casts itself back to those moments I spent in my father’s company where he was able to gently guide me around the Singapore he knew and relate it quite physically to the Singapore that we saw. I have to say it was a powerful experience because every time when I go back to Singapore, I remember that moment, that journey that I took with my father.

Aubrey Mellor

Your work suggests an interest in rescuing something that could be forgotten; and you have often talked of the power and fragility of memories. Your first acclaimed opera, The Ghost Wife (1999), recalls loneliness and violence in the Australian bush, a painful period that Australia seems to be forgetting. Singapore also tends to avoid the painful stories from the past and needs to be reminded of specifics. When we are caught up only in the contemporary we lose our roots—our emotional source—often the source of the things one doesn’t quite understand about oneself.

Jonathan Mills

My father was born in 1910 and therefore he was quite old when I was born. My grandfather was born in 1874. When I add my father’s memories of his father to my memories of my father and my own memories, I have a very different priority. I acknowledge that Australia has changed; it was always a very urban place, but its mythos came from places that were not always urban. The density of a European city is not the experience that one has of Australia. One has the experience of Australia as cities that keep rolling out endlessly – and where there is no end to its suburbia. There is a different sense of space. I wonder where are all the people? And I wonder because I am so prolifically attenuated as geographies that of course there are millions of people in each of those (Australian) cities and they are big bustling metropolises now. They don’t quite have that same density as a European City like Paris or London or Berlin. So I think even in our most urban and our most concentrated experience, the notion of what Australia might mean, to me represents something fundamentally different in terms of scale and in terms of geography and in terms of atmosphere, in terms of light, of sound and of the sheer size and scale of the place.

Aubrey Mellor

Singapore can’t keep spreading out, so it now goes upward, and is rapidly approaching the density of European cities. But issues of size, ethnicity, light, sound and scale are foremost in the minds of Singapore leaders and artists.

Jonathan Mills

The work that I’ve made, in some way, it’s always attempted to be a geography of imagination. That’s what I would say is underpinning of all the work that I’m interested in: it’s imagination and geography converging. Now, geography and imagination can be a psychological space. It can be a physical space. I am not making a judgement about where it is located. I’m saying that my particular interest in the imaginative process is necessarily mediated by geography. It is necessarily influenced by space itself. And I am always exploring and looking for those projects that will reflect in some way that notion of geography of imagination. Whether it is a woman in that perverse way, in that complex and seemingly contradictory way, in which a woman is trapped in the middle of nowhere, in endless space – especially in the European context – in the middle of vast open spaces, a woman would choose to lock herself into a tiny little hut. This simultaneous acrophobia and claustrophobia that you would experience in Barbara Baynton’s The Chosen Vessel, that Dorothy Porter so beautifully evoked in the libretto of The Ghost Wife.

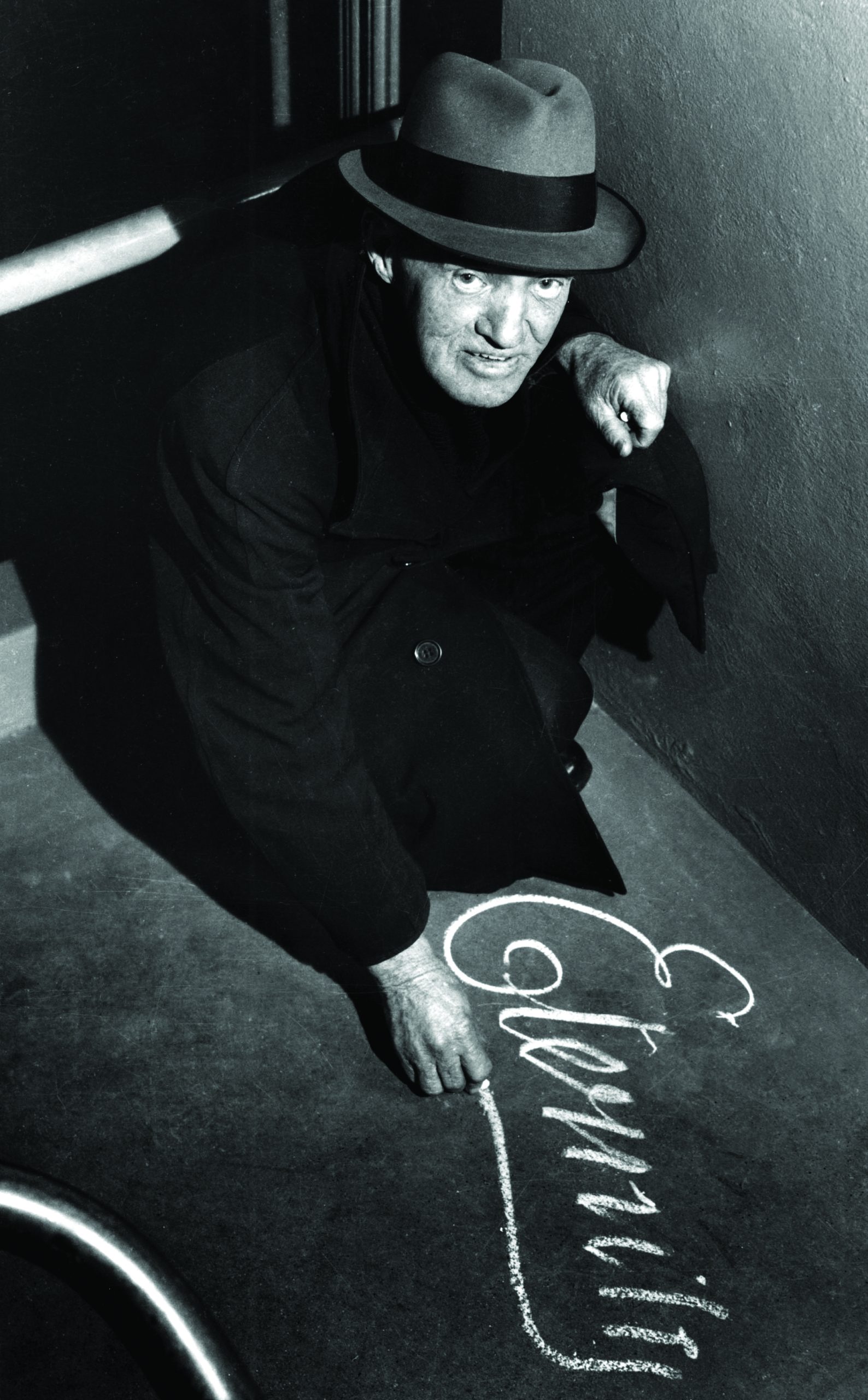

Or a geography of memory (Mills’ second opera, Eternity Man, 2003) in terms of Arthur Stace, that nocturnal vagabond who, having been saved by virtue of stumbling into the Baptist church in Palmer Street in East Sydney. Not because he wanted to ‘get’ God or wanted to listen to the word of God, or because he was particularly having a religious epiphany, but because he needed something other than methylated spirits to drink, and some nourishment. He was promised that if he went to the service and listened to the sermon, there would be tea and cake served afterwards. And so, he goes into that Baptist tabernacle and he emerges out of it with a zeal—he was almost illiterate—and he had this zeal! Let’s remember that this is a man who did all of this, fifty, seventy a hundred years before Banksy — and he goes and writes the word ‘Eternity’ all over the pavement. What I imagined, and what Dorothy imagined, was in the quiet hours of the night, this man who would go and surreptitiously write this word as a kind of tribute to the city he loved, as a reminder to it citizens of something broader and bigger than themselves. That was his kingdom. In the evening, he was the monarch of all he surveyed, and he fell across the vagabonds of the night, the woman of the night, the prostitutes and the drug dealers and people having illicit sex and all sorts of people who were the murderers and the shysters. And we know very well that Sydney has that dark underbelly, but how amazing that this man was not discovered for fifty or sixty years. He went undiscovered and everyone was speculating who the Eternity man or the person who wrote this might be, a bit like Banksy. A person actually never met or discovered. And so, again, a geography of imagination.

And in the decision to write an opera from Murray Bail’s novel, Eucalyptus, again it is consistent, I believe, with this idea that there is a geography to our imagination, not just the psychology. And so it is in that forest of eucalyptus trees, that a young girl’s fantasy starts to blossom, and it is in that paradise that her father creates for her – he doesn’t really want her to leave. His motivation is not so much keeping her in prison there but to find a companion worthy of her in her kingdom, in her domain. But he misses the point entirely, of course. He misses the point that she will only stay there, only really feel comfortable there, if she’s able to grow, if it’s able to be her idea, her history, her mnemonic. Not his mnemonic. And, in a way, it’s at the point that the story, I think, in Murray Bail’s novel is most powerful: where he starts to beautifully suggest to us the ways in which we tell each other stories. The ways in which we learnt fact or fiction, and that how wonderful is it that the person who is the walking encyclopaedia doesn’t claim the heart of this young woman, but somebody who goes to the trouble of telling her some stories. Some of them are about trees, some of them are not. They all start in that general geography of imagination and they get her thinking. So we’ve got in a sense a narrative, a fairy story that tells us some very beautiful and subtle point about the difference between how we know and how we embody knowledge. And knowledge is not about facts; it’s about an embodiment of our whole selves.

Aubrey Mellor

You take a long time to just gestate these ideas? – because they come from somewhere quite deep.

Jonathan Mills

I work slowly, and I certainly have a long time to think about Eucalyptus, because I’ve been working in Edinburgh festival for the last eight years. And so, it’s not been wasted. Every time I see a work, every time I experience a piece of music or a piece of theatre, or a piece of dance, I am constantly thinking about it as an artist. Now is the time to leave the Edinburgh festival; I enjoyed every moment of it, most of them anyway, and what I will do is I will throw myself into working on an opera. I’ve been working with a librettist, because Dorothy Porter sadly died – on any case, I think she probably she wouldn’t wanted to adapt the work of a living writer like Murray Bail. Murray was clear he was not the person to write this libretto – I think he was right: he’s not a dramatic person. So we have a collaboration in the last two years with the rather marvellous Australian playwright who has lived in London since the early 1970s called Meredith Oakes. Meredith was a student of Peter Sculthorpe at Sydney University, so her first study was music. She reads music; she is a person highly literate in music. And yet she is Australian, because I did need somebody in this opera who understood. There are many opera projects where you wouldn’t need somebody who understands the atmosphere and the physical presence of something like a eucalyptus tree – its smell, its colours and its effect of the landscape. But Eucalyptus absolutely depends on somebody who has experienced those things, and can write about them from a deep knowledge and familiarity. So I was very lucky to find in London, somebody who is highly experienced librettist and a person who is very simpatico in evoking, and very familiar with that geography.

Aubrey Mellor

The actual moment of choice, when you feel that a particular subject is going to be something you will begin work on, was that spontaneous from reading the book?

Jonathan Mills

It was certainly from reading the book but of course you never quite know, Aubrey, whether it can be done. The moment I knew it could be done was when I had a very early draft from Meredith: the structure and the clarity she brought to the adaptation suggested a very clear dramatic form to me. So it was from our work together, which is happened in the last couple of the years that I realised that this could be done.

Aubrey Mellor

I believe one’s work often comes from long dormant, personal, unresolved issues. And they’re triggered by exposure to an often-contrasted element or person. The most unexpected person you meet – and suddenly these issues come up, and you want to create from that particular point of view. You being the son of a World War II survivor, I having had uncles killed in Malaya and New Guinea, what triggered Sandakan Threnody?

Jonathan Mills

Yes. I am the son of a survivor of the prisoners of the war accounts of North Borneo and Singapore. And I wrote a piece commemorating my father’s association with Malaysia, Singapore and with Borneo as a prisoner of war. I did it, as I judged—and I was accurate, in the last possible moment I could before that generation of Australians was to leave us. So I was rather good in my timing and lucky in a sense. My father was an optimist and even though he saw many terrible things happen during the Second World War, he never ceased to be optimistic. So the framework through which I see this is rather different from that of others. I know for example, there are a lot of people who experienced the nightmares, the psychological scars that their fathers bore as a result of these experiences. I have to say I didn’t. My father didn’t particularly bear those scars; and to the extent that he was an optimist, he went to Japan for his honeymoon. He went to Japan for his honeymoon partly because he wanted to find out what was it like—because he was a very practical person. He also wanted to make sure that, before he continued to think about Japan or not think about it at all, he had some first-hand experience of Japan itself—not of a handful of Japanese military people. So I saw it from a slightly different perspective in most people and my father encouraged me to go to Japan. Such long-dormant issues gave me encouragement to think about what one could do in practical terms for the survivors of that theatre of war, but most particularly for the survivors of Sandakan.

Images of Sandakan Threnody (2004), conceived and directed by ONG Keng Sen.

Photos courtesy of TheatreWorks (S) Ltd.

The actual trigger was, I think, around 1994-1995: the then Prime Minister Paul Keating opened what was the become the first of several Sandakan Memorials, at Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park on the border of Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park in Sydney. He opened this as Prime Minister but he stayed and he talked to all of us as families who were associated with that theatre of war, as an equal, as a person who had lost his uncle in Sandakan. Keating stayed well after the cameras had gone, well after all of the media attention had vanished. He stayed and sat with a group of old men, sitting in a rather beautiful part of the Australian bush and talking to them about their experiences and listening; and desperately listening to learn about what it was like in order, if you like, to fulfil his own family’s story and to understand what had happened to his mother’s brother. He was very humble, he was very simple, he was very dignified, and he gave me the idea, actually, that this story needed to be commemorated, needed to be thought about. And as a university student I had studied a number of contemporary pieces and the title of one that came to my mind as I was thinking about what form this piece should take and it was Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. But in fact, the word that struck me was ‘threnody’, comes from the Greek word thrēnōidiā or thrēnos which means a lament, an ode of grieving. And as I undertook some research into this, I realised that because life was so grim and suffering and hardship was so widespread, in Ancient Greek, in many ancient civilisations and in many ancient societies, there was no such thing as private grief. All grief had to be public. Society would be kind of basket case if you didn’t have that rule. You had to grieve, you had to do it there immediately; you had to do it very intensely, very physically. Then you had to move on. And it seemed to me that one of the things that we hadn’t done was that. We’d done in fact the opposite. We had a society denied our grief. We had governments that determined the facts were too horrific to be shared and therefore they were suppressed. After the war we wanted to trade with Japan; there is no argument about that, and there should be no confusion between the notion of trading and the notion of commemoration and grieving. You can do the two things; it all converges into something called the collective memory, if you like. So, I was determined that what I would try and do was do something with a public act, a public act of grieving. It wasn’t a grieving or an accusation against the Japanese. It was long past that. It was grieving for our people. It was a grieving of those who died in unmarked graves, whose deeds needed to be reimagined for a moment. It was a moment also to share with those who could bear witness to it. Who could in fact still remember, either the march or Sandakan, before they were removed, as many were, to Kuching in late 1944. So it was certainly in terms of writing Sandakan Threnody, it was a piece very personal; it was a piece very public as well. I happened to have a conversation, as I was writing it, as I was conceiving it, with Ong Keng Sen, the director of Theatreworks, Singapore. We discussed, the conversation flowed; and as we discussed this idea, we realised that, actually, the three places that were essential to this evocation: one was Singapore, because it was as a result of the fall of Singapore, that military debacle where everyone thought that the invasion would come from the sea and in fact it came down to the Malaysian Peninsula. My father was a surgeon stationed at what they imagined to be behind the enemy line, only to find himself right on the front line, to quickly to be evacuated to Singapore itself. So there was a very quick change of direction and catching up of military apparatus and scheduling and understanding that led to all these people being in Singapore itself. And then they were farmed out, as we know, to places like North Borneo, to Burma, some to Japan itself. So if one is thinking about the three territories or the symbolic territories in which this particular drama plays out, one is certainly Australia; one is certainly Singapore itself and another is Borneo, and the jungles of Borneo.

So when I wrote the piece, I kept in touch with Ong Keng Sen and we made a little proposal that my music, my threnody will form a basis of another version of the piece where he would use contemporary footage, his trademark style of documentary drama, and he would bring these various elements of Singapore, Japan, and Australia and Borneo all in a convergence, which is what he did. So in effect, the one piece that I wrote had in fact three outcomes. It was a regular feature, and it won the Prix-Italia for ABC radio; it was an orchestral piece for choir, orchestra and solo tenor — the texts of which are drawn from a number of sources, psalm one hundred and thirty, the first three verses: De profundis clamavi at te, Domine “out of the depths do I cried unto thee O Lord”; then another poem, an epilogue of the poem by Anna Akhmatova from Requiem, the epilogue of which was translated by Sasha Sudakov, the Australian poet-translator who was, as you would probably remember, completely bilingual in Russian and English, coming to Australia at the age of four or five, having been born in Russia. And a poem by Randolph Stow called Sleep from his series, Outrider. Let me find the texts of the poems; I actually have them here and I’ll read them to you. The epilogue from Requiem, as translated by Sasha, goes like this, “I have learned how faces fall, how terror can escape from lowered eyes, how suffering can etch cruel pages of cuniform-like marks upon the cheeks. I know how dark or ash-blond strands of hair can suddenly turn white. I have learned to recognise the fading smiles upon submissive lips. The trembling fear inside a hollow laugh.”

The reason I chose to set that was that, in his rather matter of fact way, my father described the secret signs that anyone who has been tortured, or anyone who has been incarcerated, has for anyone else. If you haven’t been tortured, you really don’t understand the psychological dynamic of it. But if you have, you recognise the fallen face, the lowered eyes, the cuniform-like marks upon the cheeks, the fading smile upon submissive lips, the trembling fear inside the hollow laugh; you’re masking that experience, but it’s there for another who has actually been there.

In the third piece that I set — this is in three movements representing I guess three marches that were undertaken – and in the middle movement which is very much about the marches, which has the text, verses one to three of psalm one hundred and thirty, as I’ve said, the great De profundis “out of the depths do I cry unto thee O Lord”. The last movement is a setting of Sleep by Randolph Stow from his collection, Outrider. And again, you could find it, but I’ll read you the words that are most powerful to me. Halfway through the poem he says, “sleep; who are silence; make me a hollow stone filled with white glowing ash, and wind, and darkness.” And there is another verse, he says: “sleep, you are the month that will raise my pastures, you are my fire break, my homestead has not fallen.” This is a poem about a bushfire, a poem about the redemptive quality of fire, and it all it symbolises regrowth and rebirth and new beginnings, regeneration. It is also a very strange lullaby. The lullaby that says, “If only I could sleep, I could fight the fire. If only I wasn’t so exhausted, I could actually continue,” and for me, that was in fact the sentiment that I most imagined these people were thinking about as they trudged the two hundred and sixty kilometres from Sandakan on the north-east coast of Borneo into Ranau, on those death marches between January and June 1945 of which, as we know, there were only six, all Australian, who survived. My father of course was moved to Kuching earlier and did not go on the march itself. What I imagined was in their last days they were thinking about something quintessentially Australian; and that poem Sleep is both a lullaby and an evocation, a very particular evocation, of a place that would have been so communally, so mutually appreciated by all of those troops—and another kind of landscape to the one that they were in.

Images of Sandakan Threnody (2004), conceived and directed by ONG Keng Sen.

Photos courtesy of TheatreWorks (S) Ltd.

So, on every level I was thinking about in this piece: a set of relationships. What Ong Keng Sen then did was he took those relationships, those poems and that musical set of ideas and he transformed them into something that was very, very vivid; very much focusing on the particular, almost shamanistic belief systems, the animistic belief systems that one would find in places like Borneo and Malaysia. The very still and intense art forms, transformations and stories that intertwined between the Australian troops and their Japanese captors and that landscape.

Aubrey Mellor

Memory and landscape echo in all your work, and I notice you continually put horror and beauty together – very specifically in Sandakan Threnody – but what about influences – imports from elsewhere? You’ve been said to be influenced by Michael Tippett and by Benjamin Britten, or that people can hear Britten in your music; I can’t particularly, though I was thinking about Sculthorpe’s Port Essington music, with your Sandakan material. Conscious or unconscious, when you come to express yourself artistically, what of the actual music itself, is there a source?

Jonathan Mills

There are probably many. What I would say is that I start, again, from a very physical space. Music does not have subjunctive mood. It’s not a conditional tense. It exists in a very different dimension and for me, what that means is starting from very physical processes. Rhythms, I’ll give you an example. The second movement of Sandakan Threnody is structured very clearly in three parts. For me, it was the idea of the three marches that happened, and trying to make connection between them. Between a march that was very much about the physical location, the jungle, and the march that was very much martial, a march itself, very militaristic, and a march that was almost broken, that was no longer a march, it was march of ghosts, or it was a march of exhaustion, therefore it was more a chorale. But still, with the kind of forward pushing motion.

So in experimenting with ideas of how these rhythms will be generated, I spelt the word, the phrase, De profundis clamavi ad te, Domine, just that, that first sentence in the psalm one hundred and thirty. And I spelt it as a morse code rhythm. And I’ll just go to the score, because it’s been awhile since I did it. (Illustrating an example of the rhythm). Okay, and it goes on. That was the place I started from, something quite literal, something quite physical. Thinking about free-associates; I sketch a huge amount, then I start to think about my ideas, and then fragments start to coalesce and I have no idea what will be. I mean, there are others to tell me what the influences are, Britten, Tippett—not so much in Sandakan. Certainly the last movement is very Brittenesque, but that’s for me that kind of throwback and could be almost Michael Berkeley’s father, Lennox Berkeley, the composer—I mean, English Pastorale in one sense. And Tippett perhaps, but actually the first movement is nothing like those composers. If anything, the opening motif is inspired by the idea of Gagaku, the Japanese court music of the fourteenth-century. Where you have kind of the shocking sound that hovers in the air with some other things sort of pulsing beneath it.

Aubrey Mellor

Yes, the sho in particular, the reed mouth organ, wails like the proverbial banshee.

Jonathan Mills

Yes. It is a stylised version that is not Gagaku, and it is certainly not in the way that Peter Sculthorpe’s music or Richard Mills’ music deliberately references Gagaku. It is more of the kind of spatialisation of chords and texture that are held, rather than any specific detail.

Aubrey Mellor

It is interesting to hear you talk of Asian influences. Because I feel a Noh-like distillation in your work. You distil a wide range into statements of essence, but then you flare with theatrically that you can’t resist. I am very interested that the artist is very pure in you; like Oto Shoga, very Noh-like. But I love that you have what I would call a Kabuki-streak of theatricality. Could you finish with a statement about theatre?

Well, it is something I have experienced a lot of, something I have a feel for, and something I am interested in as a musician because I believe it is a way beyond the rather repetitious and almost arid, experience of music for its own sake. Don’t get me wrong: I adore people like Beethoven. But, the legacy of Beethoven was to be of such an extraordinary artist that he was able to take his own art—in ways that Mozart and Bach, and most people didn’t, even Stravinsky didn’t—into a realm of the absolute. Few artists do that. I feel that if you’re not that kind of artist, or if you’re not the kind of artist that Beethoven was at the time he was that kind of artist—so he’s not only a product of his unique mind, he’s a product of his unique times—then, actually you need to ask some serious questions about the nature of instrumental writing and how it relates to the world in which we find ourselves. Whether it is for the greater glory of God, like Messiaen or Bach provided their inspiration for, or whether it is in the service of something theatrical, like I am proposing, whether it is the entertainment of a masque, or it’s an accompaniment to a kind of mythos or a story. I think that music has lost something when it is continually insisting that it’s a pure art form and its only relationships are itself. I think that it gets very wearing, and tiring and it decontextualizes itself eventually.

I am looking forward very much to being able to stop being a festival director and start being an artist, if not full-time but most of the time. And the first project that I would be focusing on from September this year will be a return to theatre, Eucalyptus, my new opera.

Aubrey Mellor

Your operas are often called Chamber Operas, or Music Theatre, forms I particularly admire as most suited to future theatre-making, especially in Australia and Singapore. Remember Benjamin Britten’s Noh-like works, Curlew River and The Burning Fiery Furnace?

Jonathan Mills

Burning Fiery Furnace and The Prodigal Son.

Aubrey Mellor

Wonderful small-scale operas, models for what we could possibly look at here in Singapore. Sandakan Threnody is remembered with deep respect here and we look forward to more Jonathan Mills’ operas in Singapore. You would be warmly welcomed back to this major port — and, as you have said, after its colonial fall, it stands even stronger.

Arthur Stace writing his message, Eternity, Sydney, 3 July 1963.

Photo by Trevor Dallen/ Fairfax Syndication.