Bala Starr

In June I travelled from Singapore to Johor Bahru (JB), over the causeway into Malaysia, to visit Zai Kuning at his home and studio. There was a school next door, and it was a sports day, with frequent sirens and noisy cheering. Zai’s large open studio was under cover at the back of the house. Zai prefers JB to the island city of Singapore. He enjoys the peacefulness and space to work but hopes to move with his family to a wooden house nearer the sea. Once we started talking, Zai’s conversation quickly moved to the history of the Malay people and the Riau Archipelago.

At the time of this writing, Zai Kuning has an exhibition, We are home and everywhere, of new work at Ota Fine Arts, Singapore, from 27 June to 10 August 2014. He is developing elements of his ongoing Dapunta Hyang project for the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore from 20 September to 26 October 2014.

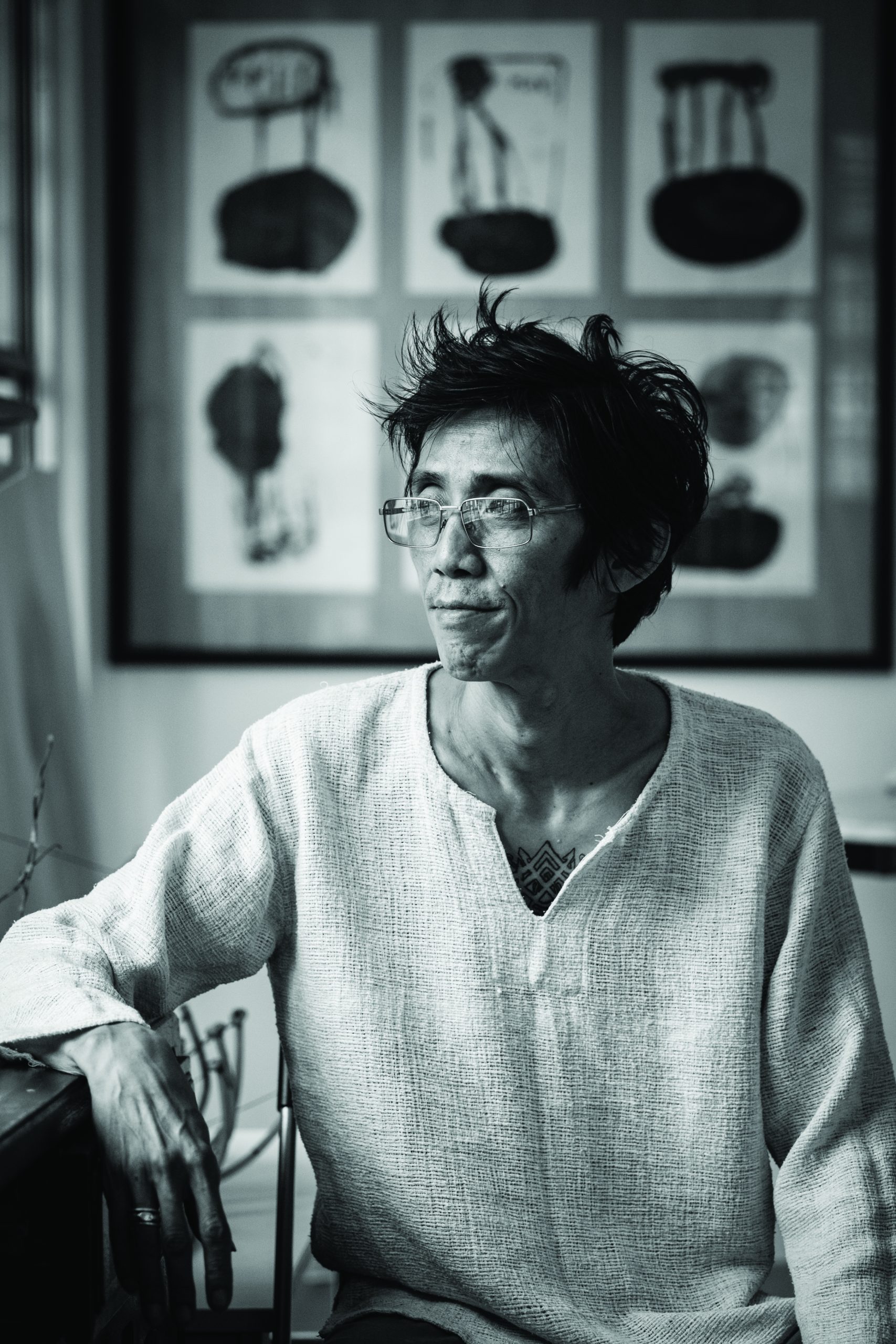

Zai Kuning

My suffering is that the Malay people don’t understand their history. The first man is Dapunta Hyang. Some people don’t like him because he is actually a figure like Alexander the Great, a conqueror. He wanted to conquer the world, and the Malay people mostly don’t know about him. Why? Politically they just talk about the history of Parameswara. But Parameswara is nothing to me.

From very young I read about him but I know this part of the history. OK, we say seventh century to thirteenth century is Dapunta Hyang. Fourteenth century is Parameswara. And they both [came] from Palembang, from Sumatra, to fight with the Johor Empire. Dapunta Hyang was the earliest king who said, ‘Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Myanmar, all belong to me’. We call him Sikander after Alexander the Great. Beautiful, but nobody knows about this story. And he is not Muslim. That’s the problem. They denied him, the whole empire denied him, because he was a Hindu and a Buddhist. In Palembang or the island of Singapore in the seventh century there was only Hinduism and Buddhism. Islam came in the fourteenth century. And that is with Parameswara as well. But he is also not a Muslim—I think he pretended only for political reasons.

Bala Starr

How long have you been working with the history of Dapunta Hyang and what was your first interest?

Zai Kuning

I would say 1999. I have been searching for these people [the Orang Laut or sea gypsies of the Riau Archipelago]. Do you know how much trouble I had? They are the original people of the islands, the sea-faring islanders who travelled from island to island to island and claimed everything as their own. But now they cannot have the rights [to this land].

Bala Starr

You are talking about their travelling and their nomadic existence, and this has also been the basis for your own research and practice.

Zai Kuning

You know I was born in a village. A Bugis village near Pasir Panjang, in the south-western part of Singapore island. We saw many islands in front of us and we always used boats. We always used ships and boats as our vehicles. My father’s side. We didn’t think about motorbikes, we didn’t think about cars. Every day we thought, can we make a boat or not?

We would always go towards the sea. We go to Pulau Bukom, Pulau Brani, and many other islands, and the boat—many different kinds—is our pride. That is the idea of a vehicle, you can go very far, very far. The better the wood you use, you go very far. Seven hours, eight hours. I go fifteen hours, eighteen hours, twenty hours. We took water, we had everything.

Bala Starr

These were the destinations of your family. Did you also travel beyond the southern Singapore islands, to the islands in the Riau Archipelago? Do you call it exploring?

Zai Kuning

No, not exploring. We are at home, because that is our home. Few hundred islands, everything is our house. We can go here, we can go there. Mixed marriage here from this island and mixed marriage there. They’re all mixed marriages. They keep moving here and there. They are not exploring, they are living their lives. This is completely misunderstood. They are completely discriminated [against]. Moving from one island to another and mixed marriages between—it’s natural. It’s very natural.

This archipelago is island-based. You know how many islands there are? Three thousand. They are not deserted. These people have been moving around in these islands for more than 2000 years. And their psychology is not the same as nomadic people who are in the desert in the Middle East or in Australia for instance. They deal with water. They deal with the sea. But this sea doesn’t have waves. It’s flat. Waves would mean South China Sea, open sea. But these Malay people were living with flat water. Their boats are different, they don’t need big ships. So that is the world that I’m living with.

Bala Starr

You talked about the different psychology of these island people. What sort of differences are you meaning?

Zai Kuning

Islanders are very peaceful. The only problem I discover is religion. Fishermen don’t need religion because fishing already is very religious. You bring food to people but this religious idea at times is too much. It’s just too much. Fishermen should be left alone. They are the ones who provide food. Farmers too.

Where I grew up it was very peaceful. We are kampong [village] people. I am a kampong boy. We climb a tree, we take a mango, go to the river. My unhappiness for the Malay people is that we have lost all this already. Everything is destroyed. We make boats, we make houses ourselves, we make everything ourselves, we don’t hire people. Now it’s all gone, of course. Only contractors make. That’s why I left Singapore and came here.

Zai Kuning

RIAU (video stills)

2003

Video, colour

29’45”

Image courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts.

Bala Starr

To Johor?

Zai Kuning

Actually we plan to move further. I want to go to Muar [a coastal town closer to Malacca, north of Johor Bahru]. I want to live in a wooden house. I think that is the best for me. It’s closer to the sea. Here we have no sea. Growing up every day I would swim [in] the sea, jump [in] the river. That’s my spirit. I am already old. I am already fifty. To think like desert always I cannot. Too dry. But I have to wait.

Bala Starr

Can we continue to talk about your sense of place, the kampong and the sea, and how your traditional cultural experience is more nomadic? How your cultural life connects with a strong sense of living and travelling by the sea?

Zai Kuning

OK. I must explain something to you. I am not a Malay man. I am a Bugis. We come from Makassar [on the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia]. The Bugis are warlords from Makassar. They were warriors. Thousands of them came to Johor because the Johor Empire had no army. This capital of colonialism came to the Straits of Malacca, to Johor and Singapore, and the Johor Empire had no army. Can you believe it? The Bugis came to Johor to defend Johor in colonial times and became the power behind the Johor Sultanate.

I am a Bugis, my father is a Bugis, my village is all Bugis. The Bugis people are strong. They always fight. They can kill very easily. Do you want me to show you something?

***

[We move outside to the studio adjacent to the kitchen. There are work benches, shelves, chairs and a low wooden platform on the concrete floor. Small table-top and larger freestanding sculptures of wood, found tools and functional objects, wax and thread are all around. From time to time the sounds from the nearby school sports activities overwhelm our conversation.]

We are Bugis. I’ll show you. [Throws a knife into the wooden platform that is part of Dapunta Mapping the Melayu, 2014.]

Always misunderstood, the Bugis. But the Bugis people are, we are warlords. Warriors. And very grumpy. [Throws knife.] The Malay people are different. The Bugis people also capture the Malay world. They are also assholes. They are not nice people. But they come to this area to serve the Johor Empire. Few thousand of them with big ships and they are good like that, very good. I was trained from young to throw a knife. But we cannot kill people. Not any more, since the time of Raja Ali Haji. He said, ‘Throw away your knife, take a pen and write’. OK, there came a point, he was telling all the warriors, because a few thousand warriors who can really throw knives, this is a different kind of problem too. And he said, ‘Stop it. Take a pen’.

Raja Ali Haji was born in Selangor (although some sources state that he was born in Penyengat, off Bintan Island, in 1808 or 1809), and was the son of Raja Ahmad, who was titled Engku Haji Tua after accomplishing the pilgrimage to Mecca. He was the grandson of Raja Ali Haji Fisabilillah (the brother of Raja Lumu, the first Sultan of Selangor). Fisabilillah was a scion of the royal house of Riau, who were descended from Bugis warriors who came to the region in the eighteenth century. His mother, Encik Hamidah binti Malik, was a cousin of her father and also of Bugis descent. Raji Ali Haji soon relocated to Penyengat as an infant, where he grew up and received his education.

He is the one who formalised Malay language with the idea of ‘unification’ as many islanders speak with different ‘lingo’. He also the one who began promoting press or printing of writing for all in Riau. As in this period most people don’t read nor write as it’s an oral history tradition. No writings but a lot of storytelling.

You know in Bintan, people are so scared of me. [Throws knife.] They all run away from me.

***

Image courtesy of the artist and Ota Fine Arts.

Photography by Tan Ngiap Heng.

Bala Starr

Zai, I’ve got to ask you about these beautiful sculptures here in the studio. This is a rib cage [points toward Justice, 2014]?

Zai Kuning

Yes, it’s a rib cage, you are right—the wisdom of the ancient world. If you want to make something float you need a rib and they [the Buginese people] studied the ribs and they made a boat. The idea that ships and boats all come from. They realised that the rib is the structure that can make it work. That’s the Bugis world.

It’s from my childhood. If you want to make something float you have to make a rib. It is a philosophy that things just grow.

There is one thing and then something else will grow.

Feel your body. There is a centre at the back. That is how the Bugis discovered how to make a ship. There must be a centre and then something at the side. Beautiful actually.