In this interview, artist and writer Ho Rui An speaks to June Yap, curator of No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia, a travelling exhibition which premiered in 2013 at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, as part of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative and ran at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore, from 10 May to 20 July 2014.

Ho Rui An

The title of the exhibition, No Country, invokes notions of transnationalism. Given that this is a regional show, specifically a show about South and Southeast Asia, to what extent does the exhibition propose looking at the region as a way of escaping the parochialism and essentialism that the national framework has too often been accused of?

June Yap

The regional scope of South and Southeast Asia was prescribed before I came into the project. It wasn’t something I had come up with. Here, we tend to think of South and Southeast Asia as two regional entities instead of one. But culturally speaking, these two have been related throughout history, if you think about how Hinduism traversed the entire region as an example. That the two entities were construed as one region allowed me to think about culture beyond the geopolitics of the nation-state. Living in this region, we have to acknowledge the influence of the entities around us.

But at the same time, regionalism itself is problematic because it sets up these binaries of say, East and West, especially if you were to read this as a project by the Guggenheim, based in New York, looking towards South and Southeast Asia as if there was no prior connection. The fact is that on a day-to-day basis, the ways in which we live our lives is extremely globalised. Even transnationalism as a concept doesn’t quite reflect this because it still assumes the nation to be that natural entity, which we know is not entirely the case, it being a condition that was established in the region only within the past century.

Ho Rui An

Interestingly, not long before you did the Guggenheim show, you were curating Singapore’s National Pavilion at Venice, which despite its contemporary inflections, still very much takes the nation as the basic unit by which we understand ourselves and the rest of the world. Looking back at that experience, what relevance do you think the nation as a geopolitical entity still holds for contemporary curating?

June Yap. Photograph by David Heald © Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

June Yap

Venice is a very nationalised platform, a global meeting of art that is constituted with very specific positionalities involved. That said, in the past few editions there have been pavilions that have refused to assume the integrity of this geopolitical definition. So we have always been aware that these are extremely problematic divisions. But in the cultural sphere, the nation still remains an effective shorthand. This is why as cultural practitioners, as much as we don’t need to obsess over it, the nation is still something we need to consider as an assumption we might explore. There are artists who are engaging head-on with this problem, refusing to be contained by these definitions. Ho Tzu Nyen’s participation in the last Pavilion, The Cloud of Unknowing (2011) was a deliberate blurring of what it meant to be a Singaporean Pavilion, especially since the references he used spanned a broader history and aesthetic.

Ho Rui An

Works like Cloud, as well as many of the works within the exhibition, are often spoken in terms of their “global” appeal. But what exactly does it mean for a work to be “global”? Is there an assumption of an international aesthetic language?

June Yap

Yes and no. There are ways to read a work within a certain vocabulary that is seen as global, such as when we read a work as a painting, a performance or a video, but these categories are themselves ambiguous. What becomes interesting for any exhibition is when you try to expand or work the limits of these categories. These categories then become frames of reference that are superimposed to get some traction, in order to figure out how close, or how far, an idea of what an artwork is doing, is in fact really what it is trying to do.

Ho Rui An

The show has travelled to two other locations since its first showing at the Guggenheim. How has the reception varied with each change in location?

June Yap

The project from its onset was intended to travel, and in this case when it moved from New York to Asia via Hong Kong, it allowed for us to consider the artworks in relation to an expanded notion of Asia, to look at how we rationalise this broader region culturally. The reception in Hong Kong was interesting. There is increasingly greater understanding of what’s happening south of Hong Kong in Southeast Asia, actually even South Asia. But because Hong Kong has been largely caught up in what we consider to be the East Asian scene, the artworks and artists still weren’t terribly familiar. There is not a lot of reason to think about South and Southeast Asia when your immediate concern is China.

But when it moved to Singapore, it returned to where the works came from. Thus here, it was more the issues within the works than notions of East and West that came into play. It was the specific content that had a more immediate resonance.

Ho Rui An

Historically speaking, the idea of Southeast Asia being an entity in itself was in part a construction of Cold War-era politics, especially through America’s involvement in Vietnam and the whole field of Southeast Asian Studies that was constituted in the wake of that. Within the show, there were also many references to the incidents of Vietnam. Given this, was there a level of reflexivity for an American audience viewing the show?

The Otolith Group (b. 2002)

Communists Like Us, 2006-10

Black-and-white video, with sound, 23 min., 5 sec. edition 2/5

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012

2012.163

June Yap

I cannot really generalise a response, but at least while we were putting the show together, working with the team, there was an awareness of what happened in the past, of these intertwined histories. Yes, there was the Vietnam War. Yes, there was the Philippine-American war. What the artworks did was bring home what exactly that meant. It nuanced their understanding. In Hong Kong, where we presented Vandy Rattana’s Bomb Ponds (2009), there was a video that showed the Cambodians relating their experiences during the bombings that were in fact meant to flush out the Viet Cong. Stories like these do not often get told, and provide for much needed micro-narratives within complex histories.

Ho Rui An

How much of a consciousness of the region did you think the individual artists and works had?

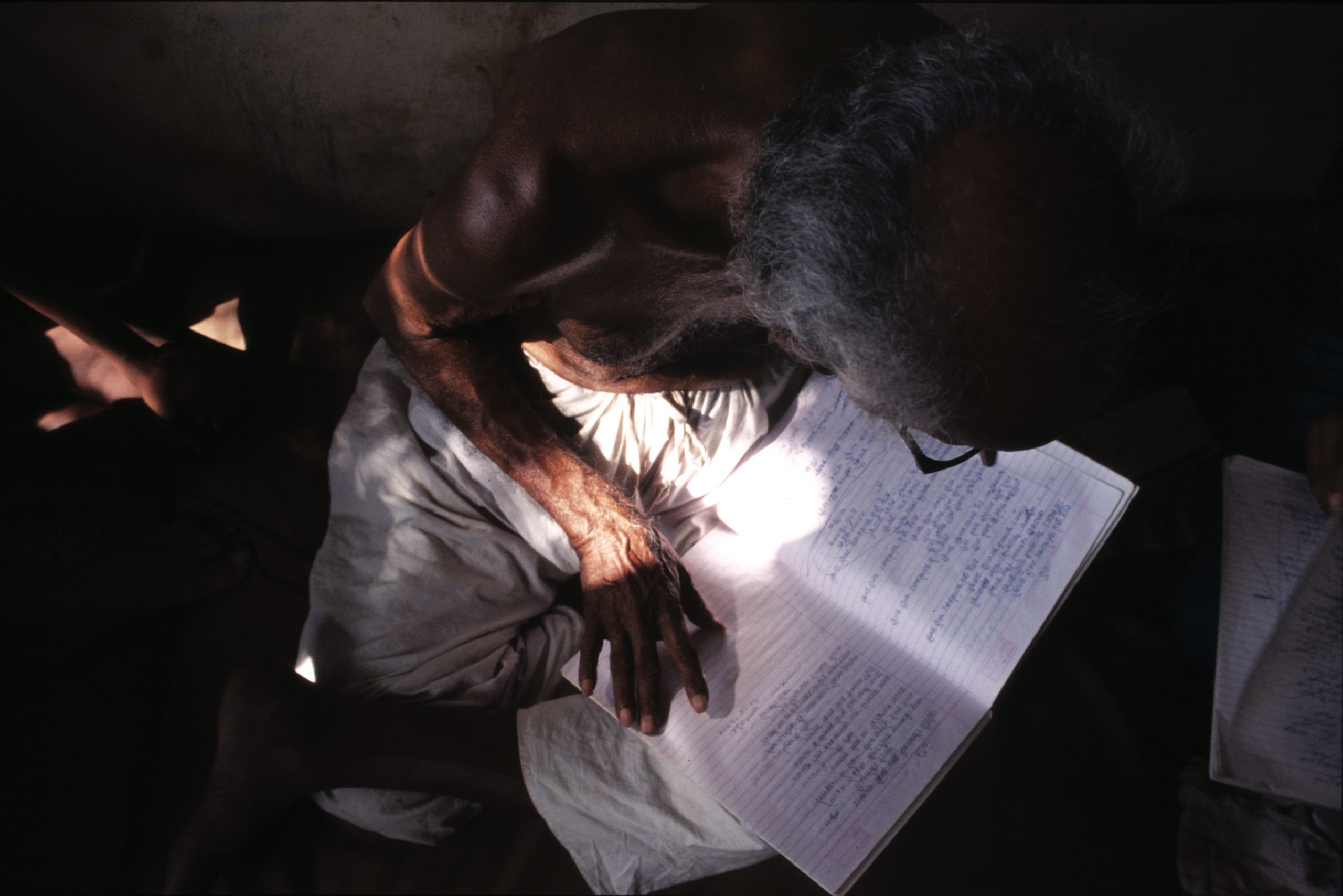

Amar Kanwar (b. 1964)

The Trilogy: A Season Outside (1997), To Remember (2003), A Night of Prophecy (2002), 1997-2003

Three colour videos, two with sound, one silent; 30 min., 8 min., and 77 min., respectively edition of 6

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Guggenheim UBS MAP Purchase Fund, 2012

2012.150.1-3

June Yap

It varied. Let’s take for instance the artwork Communists Like Us (2006–2010), by the London-based collective, The Otolith Group. Both Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun are conscious of what occurred within the region, but also of how they are not and in fact do not need to locate themselves within it. They are an example of how one can quite deftly examine and play with ideas concerning the region objectively, without losing a sense of intimacy. The images in the film come from Anjalika’s family, so there’s a very immediate, visceral connection. But there are also detached observations of its historical context, such as in the two musical pieces and the dialogue from the Godard film, La Chinoise. In this, you have the interesting tension of being close yet always standing apart. Showing the work in the context of an exhibition like this expanded the discussion beyond South and Southeast Asia. From our relationship to the Cold War, one can understand why it is here in the exhibition, yet in its slightly distanced approach you do not necessarily quite recognise it as coming from the region as well. It allows us to be more conscious of the signposts we rely on to identify representations of the region.

Ho Rui An

The exhibition is about the region of South and Southeast Asia, but there are also the regions within each country are dealt with in particular works. In Amar Kanwar’s A Night of Prophecy (2002), it is the regions within that are doing the work of testing the stability of the nation-space that is India. How do you deal with the complexities of the regional at such a specific level?

June Yap

One jumps right in, which is what Amar Kanwar does. A Night of Prophecy does that, moving from Maharashtra to Andhra Pradesh to Nagaland to Kashmir. There is no preamble, no apologies, and that’s what is significant about that work. I appreciate how it doesn’t begin with the binary of centre and periphery, and then tries to work the periphery until it takes over the centre. It just quite plainly shows you that this is what the reality is, and one has to recognise and deal with it.

What are your aspirations for this final staging of the show in Singapore?

Ho Rui An

I don’t really set the outcomes. For me, it’s more about the process. You try something and then find out. With this project, I was attempting to complicate the ways we represent the region, because I have observed artists doing that as well, engaging directly with the problems of being pigeonholed.

June Yap

An exhibition is not the endpoint; rather, it’s a continuing process. Curatorially, you learn something from each project. It’s all part of a larger process of thinking about what you can do with art, how cultural discourse is being created and where you come in. After all what art does is not limited to the aesthetic sphere; its implications are more far-reaching than it often appears. With each project, you learn more about what art can do. The question is with this knowledge, how do you respond?

Installation shot of No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia,

theinaugural touring exhibition of the Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative,

at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore,

a national research centre of the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), May 10, 2014 – July 20, 2014.

Courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, and the Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore