He Zhiyuan

For most Singaporeans, the history of the island-state begins in 1819 with the arrival of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who established it as a trading port for the East India Company. But you chose to begin your artistic career in 2003 with Utama – Every Name in History is I, an installation of paintings and a film about Sang Nila Utama—the neglected and forgotten pre-colonial founder of Singapore. Was this beginning at the pre-colonial beginnings of your country a deliberate choice?

Ho Tzu Nyen

There is a story about Raffles that I really like. In 1823, while living in his newly constructed bungalow on Bukit Larangan in Singapore, Raffles suffered from a bout of tropical fever. In the throes of his delirium, he received a vision or perhaps a visitation by the Malay kings who had come to this island some 500-600 years before him. It should be said that Bukit Larangan, in Malay, means the Forbidden Hill—so named because it was the sacred burial grounds of the ancient Malay ruling dynasty. Upon waking up, and still depressed, Raffles wrote to his friend William Mardsen, saying that the tombs of the Malay Kings are close at hand; and that if it is his fate to die here in Singapore, he shall take his place amongst these. Just as he has walked in their footsteps in the ‘founding’ of Singapore, he now dreams of following them to their graves.

Raffles was a child of the Romantic Age, which was the great age of dreams of origins and originality. And perhaps this romantic predisposition made him particularly sensitive to a form of haunting—a haunting by one’s predecessor, a feeling that one owes a debt to a precursor that can never be discharged, because the debtor is a phantom, a ghost-father. Ghost-fathers come in a multiplicity of guises and names. But to tell a story, one has to begin somewhere, and I chose to begin with Sang Nila Utama, the first king of the Malays, the one who was said to have given Singapore its name.

Utama was believed to have arrived on the island between the 13th and 14th centuries when he spotted a lion along the shores of the island, and thus gave Singapore its name. In Sanskrit, ‘Singa’ means lion, while ‘pore’ is derived from the word ‘pura’, or city. This founding was described in a most spectacular fashion in the The first edited text of the Sejarah Melayu, or the Malay Annals, was edited by Abdullah bin Abdulkadir Munshi (1796-1854; usually referred to as Munshi Abdullah) and published in Singapore in about 1831, though there have been disagreements over the actual publication date.’]Malay Annals:1 ‘And they all beheld a strange animal. It seemed to move with great speed; it had a red body and a black head; its breast was white; it was strong and active in build, and in size was rather bigger than a he-goat. When it saw the party, it moved away and then disappeared. And Sri Tri Buana (another name for Utama) inquired of all those who were with him, “What beast is that?” But no one knew. Then said Demang Lebar Daun, “Your Highness, I have heard it said that in ancient times it was a lion that had that appearance. I think that what we saw must have been a lion”.’

But lions have never been a part of Singapore’s eco-system. To begin at the beginning is always to begin with fiction, and as fiction.

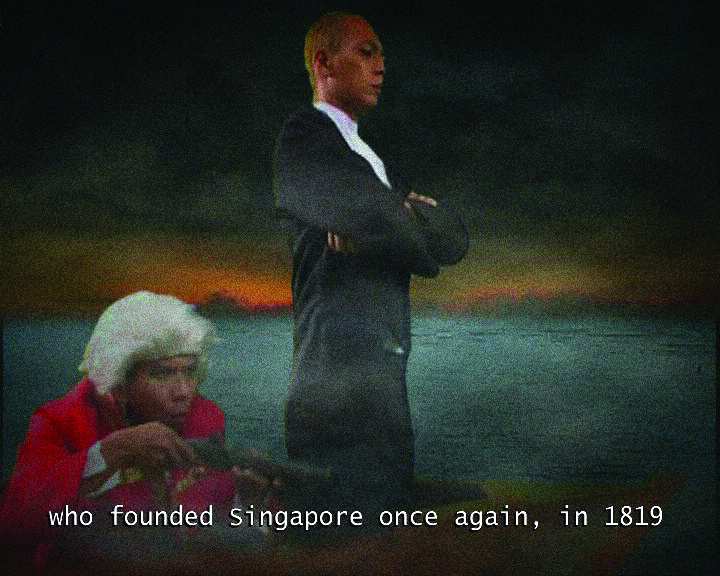

Raffles on his voyage of discovery. Still from video component of

Utama – Every Name in History is I (2003), DV, 23 min.

He Zhiyuan

This passage from the Malay Annals reminds me of the primal scene as it has been staged in psychoanalytic discourses – the moment where a child encounters a re- enactment of his or her own origin, which Freud dramatised as a traumatic witnessing of parental intercourse—an experience marked by sexual agitation and violence and which can only be recollected by the child in a disguised form.

He Zhiyuan

Freud was one of the greatest poets of originary myths. And the agitation and violence that you mentioned saturates the scene of this encounter with the ‘lion’. It is embodied by the great speed and monstrous appearance of the chimera. To contain this trauma, the chimera must be domesticated by being given a name. And in turn, this process of naming opens up to a process of wish fulfilment. We must understand the phantasmic projection of the lion as a manifestation of the desire to establish a new dynasty founded upon the legitimizing authority of the ‘singasana’ or the ‘lion throne’, a major symbol of Malay and Indonesian royalty. From the absence at the heart of origins, theatre emerges—theatre as simultaneously concealment and the projection of power.

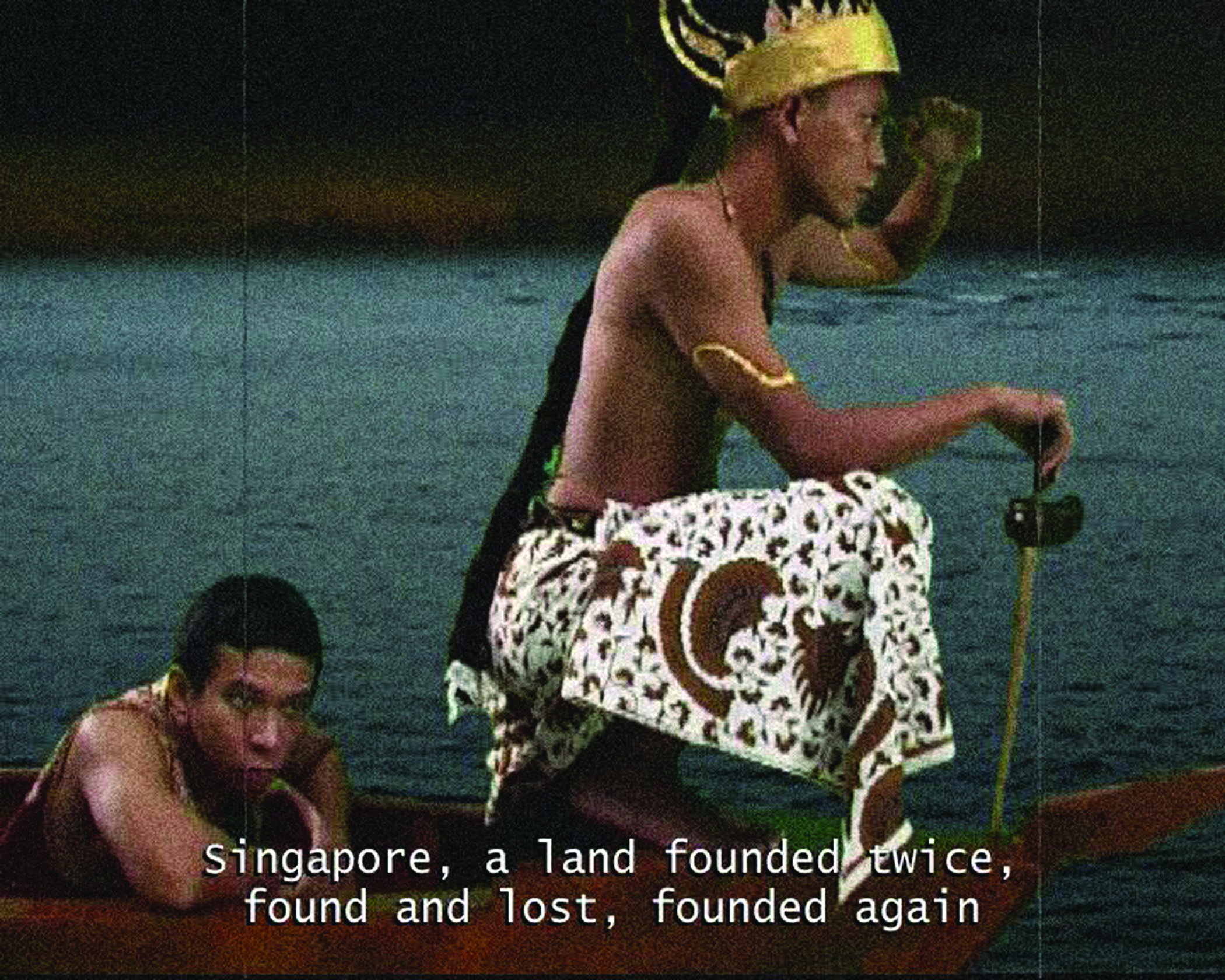

Utama on his voyage of discovery. Still from video component of

Utama – Every Name in History is I (2003), DV, 23 min.

Utama at the Hunt for the Lion of Singapore

Painting from Utama – Every Name in History is I (2003), acrylic and ink on canvas