Joleen Loh converses with Samson Young about his long-standing interest in the relationship between sound and violence. Young’s multidisciplinary practice often takes the form of sound installations, radio broadcasts, performances and graphic notations, all of which generate multiple, intersecting narratives around the topics of military warfare, political borders, histories of migration, and cultural identity. Trained as a classical composer, his approach is informed by a diverse range of sources from the avant-garde compositional traditions of aleatoric music to musique concrète and popular music, as well as current affairs, colonial histories, musicology and philosophy. This conversation unpacks some of Young’s critical thinking around the role of sound within a constellation of political, technological and cultural conditions that govern social experience.

Joleen

Hi Samson, I would like to begin by acknowledging one of the central themes for which your practice is well-known—the political and socio-technological dimensions of sound. These, for instance, constellate in your work Nocturne (2015), an on-site performance in a gallery space in which you used found footages of night bombings—mainly of the US attacks on the Middle East—and approximated its sounds using Foley techniques. By way of contextualisation, can you introduce some of the conceptual interests underlying Nocturne?

Samson

Nocturne grew out of several previous projects. In Liquid Borders (2012–2014) I recorded the vibration of the border fences between Hong Kong and China. After Liquid Borders, I started to look beyond the borders of those regions and started thinking more broadly about lines of control, which led to another fieldwork-based project titled Pastoral Music (But It Is Entirely Hollow) (2014–ongoing). In that work, I focussed on a military defensive system in Hong Kong called the Gin Drinker’s Line. It was a collection of underground bunkers and pill boxes that ran along the Kowloon Peninsula, which was built by the British in the 1930s. Although the research that surrounds the Gin Drinker’s Line has not yet finished, it did get me interested in the history of the Second World War in Hong Kong, and the way that the story of our involvement in it is told. This eventually landed me on the set of themes that Nocturne looks at. These include thinking about how geopolitics determine the way histories are told, and how that shapes people’s self-perception. [I was also] thinking about Hong Kong’s place within larger geopolitical structures and the role that it played during the Second World War, or the lack thereof, in the history that I’ve read.

It is also important to mention that Nocturne was only one part of an exhibition that was titled Pastoral Music (which, is different from Pastoral Music (But It Is Entirely Hollow) which is a single project); it was first shown at Art Basel Hong Kong and then subsequently at Team Gallery in New York. To put together this exhibition, I looked outside Hong Kong and started to think in more general terms, about how wars are represented in films and work of literature, and how wars are represented in the media. And this is pretty typical of my thinking process—I begin with an observation that is ‘closer to home’ and that broadens into something that is more universal.

Joleen

Looking back at Nocturne now, were there ways in which these questions around the representations of war were ‘resolved’ through the work?

Samson

I think I came out with a better understanding of what triggers the audience’s imagination, how to get the audience thinking, especially when an artist is dealing with a topic that is already over-determined, such as warfare. The world doesn’t need another artist to make a work about how horrible war is to arrive at that foregone conclusion—and that’s not what Nocturne is about. On a personal level, I was dealing with the sense of guilt that came from wanting to engage with this topic in the first place. At the time I had a lot of anxiety over my place in this conversation: why am I making work about this topic? Was I aestheticising violence, and what am I really doing by unleashing this thing unto the world? I now realise that the really important question is not how I justify my position, but what sort of artist-audience relationship I end up creating through this experience we call art. In Nocturne, when a member of the audience picks up that radio unit to listen to the performance, when they press it against their ears to experience this wash of gentle sparkles that claims to be some version of night bombing, then they are implicated in the same sort of discomfort that I feel when performing the work.

So that’s the affective dimension of the experience. In terms of how I think about the whole issue though, I am just as confused as when I first started making the work, and I’ve learned that it is OK to not have clarity. I am not some sort of a guru with a very specific insight that people should listen to. So you can say that the ‘resolution’ that I came to is just a clearer sense of my relationship with the work.

Joleen

Instead of confronting audiences of Nocturne with the realities of conflict outside of its aestheticisation as Hollywood spectacle, would you say that they were doubly removed from it in their encounter of your reinterpretation of collected video clips using Foley techniques? If so, what did this distancing between the origins of these sounds and your audiences mean to you?

Samson

I would argue that it’s actually drawing them much closer to it. What I mean by that is—I have to explain this in a roundabout way with the example of a live concert. When you are in a live concert with amplification, what you are experiencing when you are listening to the singer and the band is mediated by a network of cables, consoles, amps and speakers. Now, imagine that there is a two- or 10-second power outage or malfunction. All of a sudden, the amplified signals drop out and you are left with the natural acoustics of the space, and you become, for a split second, hyper aware of the fact that the experience that you just had was very mediated, i.e., it came through the electrical circuit: the mic goes through the mixing board and then eventually out through the speaker. The technology that carries the signals is absolutely designed in such a way that you don’t notice it. That’s actually the very definition of the success of mediation, which is that you don’t notice it. So if there is a different kind of measurement of craftsmanship that is specific to these devices of mediation, it is that ability to be invisible and inaudible to you. I think what Nocturne was able to achieve for the audience is that it made that process of mediation—not unmasked but—intimately felt.

When you are walking through the gallery space, this is what you experience. You hear me tapping very lightly on the drums and you hear these very soft sounds in this space. First you experience these sounds unamplified and you don’t really know what’s going on, except that it looks like a guy is doing Foley. And then you pick up a radio, you tune in to 101.5FM and hold it next to your ear, and then you suddenly realise, as you are going around me, what I’m doing, which is doing Foley to films of night bombings. And, secondly, you hear my hand, which when you first walked into the space was very far removed from you sonically, and it’s doing these little gestures and the sounds are very small. But then, all of a sudden, these sounds are in your ear and you realise what I’m doing. You become aware of the pathway through which this sound has travelled, which is into the computer [where it is] processed, up into the air, through the FM airwave and then back down to you through the reception of the radio.

All of a sudden that pathway becomes very obvious to you as you are experiencing these very intimate sounds. That’s what it does to you, and whatever effect that has on you, it will carry into other aspects of your life. What does that mean politically? I don’t know, but here’s the thing that it does to you. And of course, this experience is not separate from the topic that I am looking at in Nocturne, because that’s what gives it its contradiction, that’s what gives it this really weird fucked up-ness. [It makes people question] what this artist is doing, who he is, who is doing this, and why he is aestheticising war… All of those things combined are the effects it has on the audience.

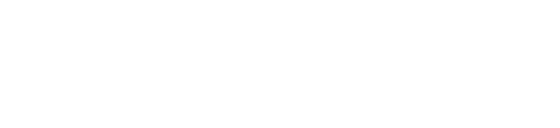

Samson Young, Nocturne, 2015.

Sound performance (one performer with airsoft pistol, audio interface, bass drum, compressed air, contact microphone, cooking paper,

cornflakes, electric shavers, electrical sound toys, FM transmitter, glass bottle, laptop, mixer, ocean drum, rice, Shinco radio, shotgun

microphone, soil, tea leaves, thunder sheet, thunder tube, Tupperware, video, wind chime).

Installation view of Pastoral Music at Team Gallery, November 5–December 20, 2015.

© Samson Young. Image courtesy the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

Joleen

You once said that “music can be very dangerous.”

Samson

What I meant by that was that music bypasses the defences that we have—call that intellect, education, informed opinion—and crosses into the emotive or the affective. It’s dangerous because you know it can be manipulative, but in that moment [of exposure] you still can’t help but feel the things it wants you to feel. Over time, we have seen many examples of how that power has been harnessed.

Joleen

That reminds me of Brian Massumi’s analysis of the US colour-based terror alert system introduced by the Bush administration in 2002, as capable of calibrating and triggering collective emotional responses. He argued that, emptied of semiotic content, these colours are able to bypass cognition and work on a person’s pre-subjective level to modulate an intensity of emotions. In this way, politics directly addresses pure perception—all our senses can be conscripted. Today we navigate and compose our relationship to the world through a much more complex architecture of data across different technologies. Images and sounds, such as those we see in the news or in films, have become a major player in contemporary affective economies, and your work allows us to recognise these affective mediations. What does an ‘intelligence’ in listening mean to you?

Samson

I’ve talked about how music affects us psychologically. Our receptiveness to it is hardwired, and it is hard to resist being moved—kind of like being moved by a really bad movie—but it’s important to understand what it’s trying to do and moderate its effects on you. As an artist, I am also interested in the question of how one would, for example, engage with the intensity of violence and terror without recreating those scenarios of violence. I think that’s what art has always done very well. The result is, again, that this experience will radiate horizontally, so that it is no longer topical but it becomes a much broader thing.

Joleen

In your works, you deploy unconventional ways of lifting the curtains of illusion and revealing otherwise overlooked processes of mediation. Is the exposure and deconstruction of these underlying ideologies enough for you?

Samson

No, it’s not enough, and that is not where the experience rests at. If you allow me to speak abstractly, where the representational—the ‘extra-sonic’—meets the ‘form,’ that’s actually a space of imagination and a space of extremely heightened intellect and sense that happens in the mind.

This has happened in music for centuries. Think about what happens in the ‘programmatic music’ of the classical period. Take Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, just for argument’s sake. It is in five movements, it is about these beautiful lines, it is about these intricate sonic and harmonic structures, which invites very formalist listening. But it is also about this extra-musical idea called pastoralism, which is a whole basket of complicated issues. What is happening in your mind is that you are processing these pure forms, and you have to be very focussed on processing them, but you are also engaging with the idea and imagery of pastoralism, so you are using both the left and the right sides of your brain, and you might even begin to perceive pastoralism not as an idea, but as forms. I truly believe that whatever knowledge and awareness you would have gained from this cross-breeding of the formal and the extra-musical would be general and nonspecific. I think that’s what some of the earliest pioneers of sound art like Pierre Schaeffer got wrong. De l’objet sonore or the idea of focussing on the formal aspects of sounds was reactionary and a much-needed discussion at the time, but we shouldn’t be dogmatic about it because it also negates this whole other thing that happens when form and content collide.

I am always thinking about compositional form when I am making sound installations. It’s never like I am just playing this field recording, and that this recording represents something, and that’s where things end. Even with the birdcall piece in Canon (2016), there is a compositional structure to the experience. That’s hard to talk about in the contemporary art context, because contemporary art writing doesn’t have the language to and isn’t really interested in talking about musical and sonic forms. But I never just put a sound out there. It must have a form, it must be something which I actually want to listen to.

Joleen

Can we talk about Possible Music #1 (2018), your new commission for the exhibition One Hand Clapping at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum? In this new work, you crafted several compositions using an array of ‘impossible instruments’ that you generated in collaboration with Next Generation Sound Synthesis (NESS), a laboratory that specialises in physical modelling to replicate and extend upon the sounds of well-known musical instruments using sophisticated algorithms. These compositions, reminiscent of military bugle signals, are periodically played through a constellation of speakers in a room that has been both carpeted and painted in highly saturated blue and teal hues. While some of these imagined instruments can remain only in the digital realm, you have also recreated parts of them through 3D printing technology for this work. There’s a lot going on here. Could you elaborate on the different trajectories that are augmented by this multi-layered work, and how it was conceived?

Samson

The new pieces are the most difficult to talk about because I don’t have that sense of distance from it yet. But I think I allowed myself to be a little more improvisational and playful. Although Nocturne and Canon were very eclectic and had several narratives intersecting within them, the presentation was cleaner. With Possible Music #1, you kind of walk into the room and think, “what the fuck is going on?” I really liked that. I think that’s a significant change for me in terms of a working strategy.

I was going to do something else at the music department of the University of Edinburgh and they told me about the physics department’s NESS research project, which makes physical models of musical instruments. What scientists tend to do in physical modelling is describe the physical properties of a musical instrument, such as its dimensions, the material that it is made of, and the temperature of the breath [that enters it]. With those physical parameters, they can get the computer to simulate the behaviours of those musical instruments. So I went into the lab to use the software and I started messing around with it and made instruments that wouldn’t be able to exist in the real world. Because once they become numbers, the computers don’t really care, right? You can create a 20-foot long trumpet or a trumpet that is activated by 300-degree breath, and the computer is going to give you the sound according to its algorithms. So I started messing with the software to stretch its limit, and to make the kinds of sounds that only this software can make. I created about 11 different instruments and, with them, I generated about 60-something compositions, out of which I chose 40 to include in the piece.

That’s how I approached the research and how I got to making the piece. The big sculptures you see coming out of the walls, that appear cut by them in strange ways, are actually mouth pieces of these imaginary instruments that I have created, made to the scale. For example, there is a green 2.9-metre mouthpiece, so you can imagine how big that trumpet would be if the mouthpiece was that big. I also 3D-printed a small rose gold trumpet part for a nano-trumpet that I created [using algorithms]. There is also an animation showing a dragon in the stadium. You see a dragon flying into a football stadium and breathing fire into the trumpet, and that is supposed to be the illustration of the 300-degree trumpet, one of the digital objects I have created for this piece.

Joleen

This is the first time you collaborated with NESS. What was significant for you in working with scientists and algorithm specialists?

Samson

The physics department in Edinburgh are world leaders in physical modelling in the field of computer music. The folks at NESS are not only doing physical modelling, but they are using super computers and parallel computing to make these physical models, which in a nutshell just means that they are able to account for and compute in real-time a richer set of physical real world properties. What that means is that they can make the claim that their musical instruments are more accurate, because they sound more like real instruments. I am very interested in that claim, this scientific claim of authenticity and how the value of that research rests upon the idea of the most authentic renditions of these instruments. It also boggles my mind that the measurement of success for new algorithms and software is pitched against whether it is close enough to something that we already know.

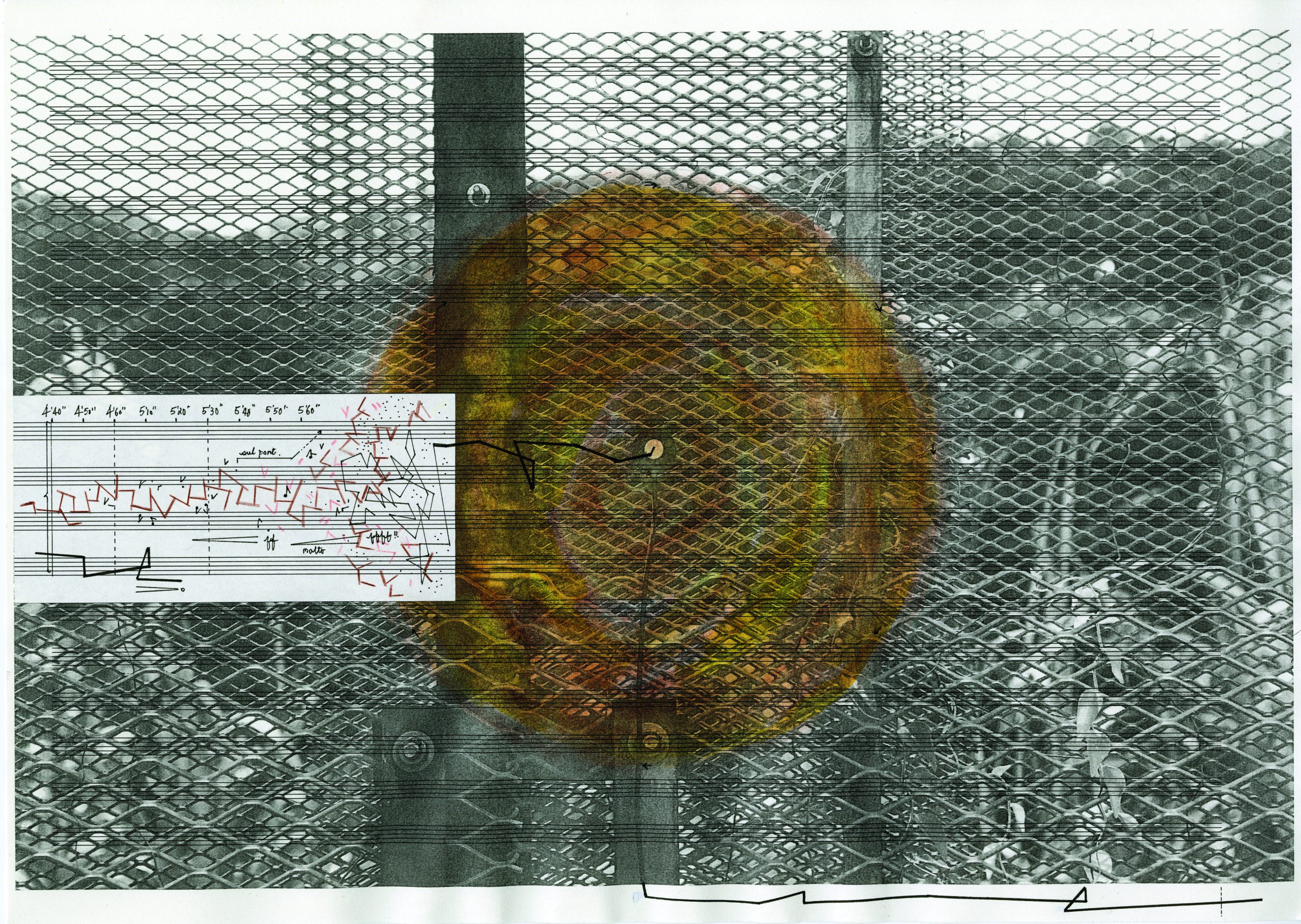

Samson Young, Canon, 2016.

Drawing (charcoal, ink, pastel, pencil, stamp and watercolour on paper), sound performance (one performer with audio interface,

laptop, Long Range Acoustic Device (LRAD), microphone), installation (3D printed water basin, custom-designed bench, sound

track, stamped text on wall, wired fencing).

Installation view of A dark theme keeps me here, I’ll make a broken music at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf,

December 17, 2016–March 5, 2017.

© Samson Young. Image courtesy Galerie Gisela Capitain and Team Gallery. Photo: Simon Vogel, Cologne.

Joleen

What assumptions do you think ground these notions of authenticity—and its fetishisation—and what, in your opinion, are the shortcomings of thinking in such terms today?

Samson

There is a danger in saying that we should do away with authenticity altogether, because moral relativism is never good. But there are moments where you realise that such words or concepts have become so over-determined that they cease to be useful. You might be thinking or talking about something which is similar to the concepts that the work is trying to describe, but because of such over-determination and a variety of other reasons—maybe you are on the wrong side of history, maybe you are part of an ethnic minority group or in terms of your sexuality. Whatever the case, you are not the person in control of that narrative, so it might be better to abandon those terminologies not only because they are over-determined, but because they polarise people.

I’ve been thinking about whether authenticity is one such word. But this is me intellectually speaking right? I am not saying it has anything to do with the work, but this is something I have been thinking about. There is a danger in doing away with Authenticity with a capital ‘A’ altogether, because it’s very easy to say, “we are all specific, so you should just respect my specificity.” But one can also overstate that argument. I don’t know if I have arrived at any conclusion yet, but my hunch is that music is a really good way to think about this. It’s a safe way to have thought experiments, because it’s one of those things that people really care about, but they don’t care about it enough that they would kill each other to win an argument, you know what I mean? People care about music and each person has an opinion about music, and they will engage in a debate with you. Music is something very special in that way, in fact.

Samson Young, Liquid Borders I (Tsim Bei Tsui & Sha Tau Kok), 2012-14.

Ink, pencil, watercolour, Xerox print on paper.

© Samson Young. Image courtesy the artist.

Fieldwork documentation.

Joleen

There are several other visual and sonic components to Possible Music #1. Apart from the 3D-printed sculptures, there are also artificial flowers attached to floor-mounted speakers, two animation videos, graphical notations, and a flag. Can you say something about these elements that you’ve brought together in the work?

Samson

The other thing that I wanted to create in the space was an impression of an artificial war memorial, somewhere between a roadside memorial and a war memorial park. The sign at the front (which shows the daily schedule of the signal calls coming from the sound installation) looks like it’s on a piece of black marble, and it gives off this impression of a fake war memorial. There is also a video documentation of a drumming performance by Shane Aspegren. There are aerial shots of him doing these drumming patterns, tracing a three-point pattern on the floor that mirrors how the sounds are channelled in the exhibition space. He has 10 different patterns that he plays continuously for one hour. When the trumpet calls over the floor speakers are not playing, you hear the drumming and it is making these geometrical shapes through the speakers. But when the trumpet calls come on, you get all 10 speakers making sounds at once and these sounds spin around in the room. So there is a very implicit reference to the military marching band.

Joleen

This brings to mind the role that music has played in military discipline and mobilisation, and one can perhaps add that to other forms of institutional governance. Is there an implicit critique for you in foregrounding the militaristic origins of the marching band?

Samson Young, Landschaft (Angel Gates Park, San Pedro, Sep 16, 9.00am), 2015.

Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper.

Image courtesy the artist.

Samson Young, Landschaft (Fez, Jannery, Sep 5, 10am-11.15am), 2015.

Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper.

Image courtesy the artist.

Samson Young, Landschaft (Rouen Cathedral (side garden) (slightly different position), Aug 22, 3.15pm-4.15pm), 2015.

Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper.

Image courtesy the artist.

Samson

So, to return to the idea of authenticity, I have been thinking about how we regard authenticity and cultural appropriation, especially in music. I think the marching band is a good and interesting example because the marching band, at least in the American high school system, is such a festive and almost bizarre celebration. And obviously it has a military origin. However, throughout the ages, through appropriation and re-appropriation, it has kind of shed its military origin, a violent origin, and become this pure form. So, all these things are part of the thinking of Possible Music #1. That’s usually how my pieces are; I will start with an idea and like—OK, I’m working with scientists to make these impossible instruments, but it becomes a point of departure as my mind goes in all kinds of weird directions which is all tied together in a form. They don’t really come together conceptually or narratively but they become this weird collage in form.

Joleen

It seems like a queering of the war memorial site. What I mean by that is the deliberate deconstruction and subversion of conventional representation, from its rituals to its ceremonies, where notions of reality and artifice are deliberately toyed with.

Yeah, everything is sort of artificial and a little bit over the top. I am juxtaposing things and [have juxtaposed] a marching band reference to these artificial objects on the wall, as well as drawings that look very sensitive but were actually mediated by the computer and were all done by the plotting machine (but they look like they were done by hand), and these fake plastic flowers. (That’s what I find interesting about artificial flowers. You know full well that they are artificial and that they are not real but there is still an urge to touch them, to verify that they are not real. That urge is very real). By juxtaposing all of these things together I think each of the individual things that I am referencing spins new meanings without giving an explicit framing of what I think about them. It’s not a random selection, they have some sort of relationship with each other, but there’s no clear guidance from me on what you should think about them, but when you put them next to each other, they spin new meanings.

The author thanks Shahila Baharom for the original transcription of these conversations.

Caption: Samson Young, Landschaft (St. Paul + Peter’s Cathedral (side courtyard), Sep 2, 10.50am), 2015.

Ink, pencil, watercolour on paper.

Image courtesy the artist.

Samson Young, Possible Music #1, 2018.

Four 3D-printed sculptures, two framed watercolour and soft pastel on paper, costume with wool thread, artificial flowers, lamé,

polyester, and silk flag, feathers with dye, felt-tip pen on drumhead, video with sound,

62:20 mins, silent video, 0:40 mins, 11-channel sound installation.

Installation view of One Hand Clapping at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, May 4–October 21, 2018.

© Samson Young. Image courtesy the artist. Photo: Ji Hoon Kim, New York/Seoul.