If the condition of an institutionalised object is defined by its muteness, then its sovereignty is surrendered to another. The label, the description, the extended text, by any other name, provides this voice. It vocalises, its words declarative, at times confessional, to assume a nakedness of meaning, wrought in a diligence for clarity, a singularity doomed to repeats, re-enactments: encounters remarkable in its narrow significance. The exhibition text is susceptible, disciplined by classification, category, pre-empted by intent, conditioned by a logic it could not resist. Site, building, institution could do no more than conspire. This is perhaps unsurprising, where aesthetic resonance is often neutralised and calibrated to ideological contingencies, and even if judicious, acknowledged to a function of its time. The task is perhaps to return the object to its proper constitution as Art, having relations to the contemporary, as consignments to an audience conditioned, but not lost to dogma: to prompt the agency of listening, to know what is not ‘sayable’ is audible; to stir, but not to replace dogma with dictates.

The following are selected images from current and past exhibitions at the NUS Museum, National University of Singapore. They are not assembled in this publication to propose a congruency of curatorial themes, but to allow a consideration into a textual field built around encounters, made performative as a series of fragments, from the banal to the academic, audible in their own agency and origins, but relationally deployed. It is not a matter of the contextual to limit such encounters to an exercise of comprehension, but to suggest the virtue of opacity and what it may offer as renderings that complicate.

Where necessary, texts that appeared in the exhibitions are reformatted for the purpose of this publication.

Extract, curatorial notes from “There are too many episodes of

people coming here …” [projects 2008-2014], 2016.

Curated by Kenneth Tay.

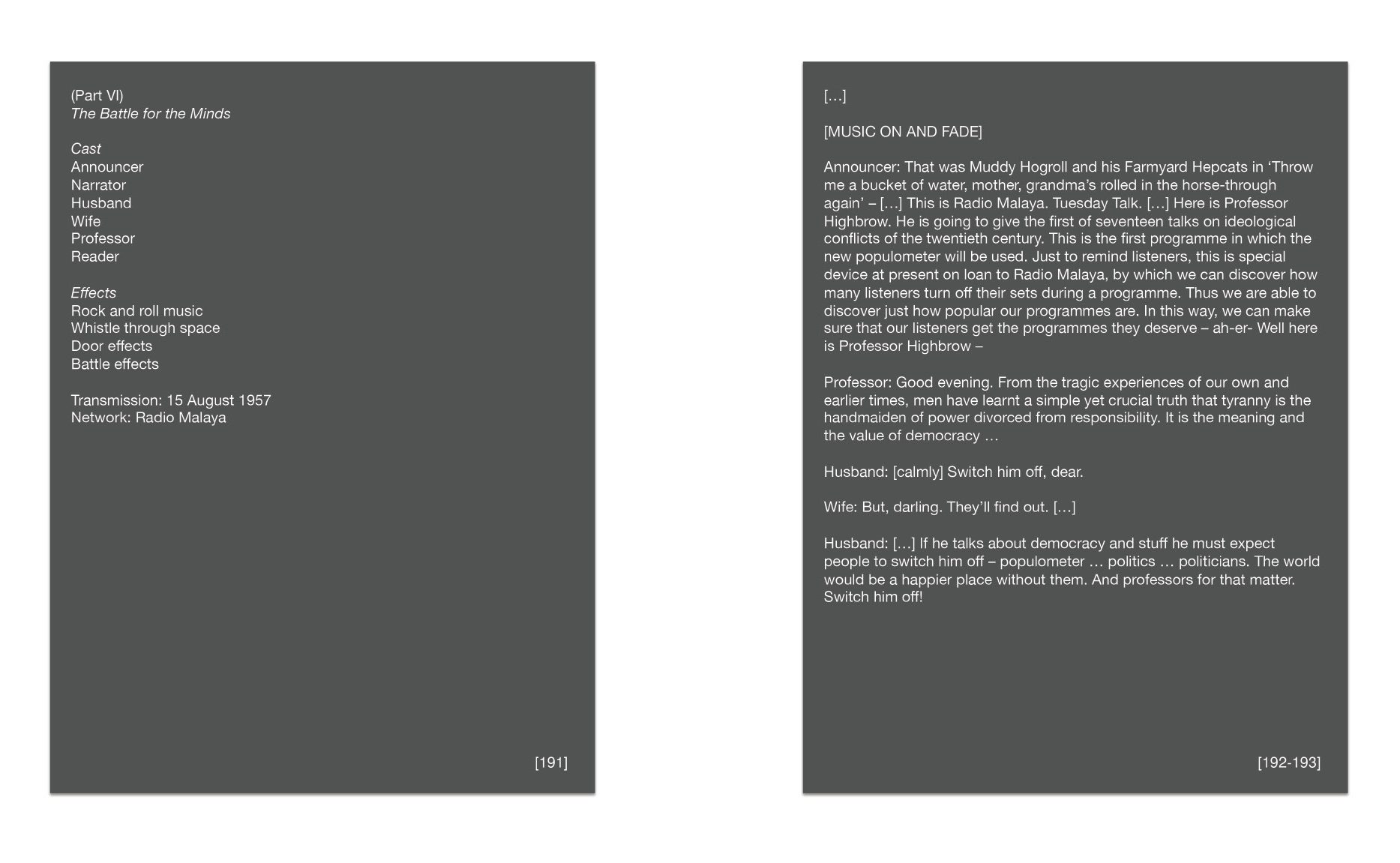

Fragments, texts reproduced from A Nation in the Making (Part VI),

a six-part play by S. Rajaratnam written in 1957.

These radio scripts were first broadcast on Radio Malaya from July to October 1957.

The play is published in full in The Short Stories and Radio Plays of S. Rajaratnam by

Irene Ng (Singapore: Epigram, 2011).

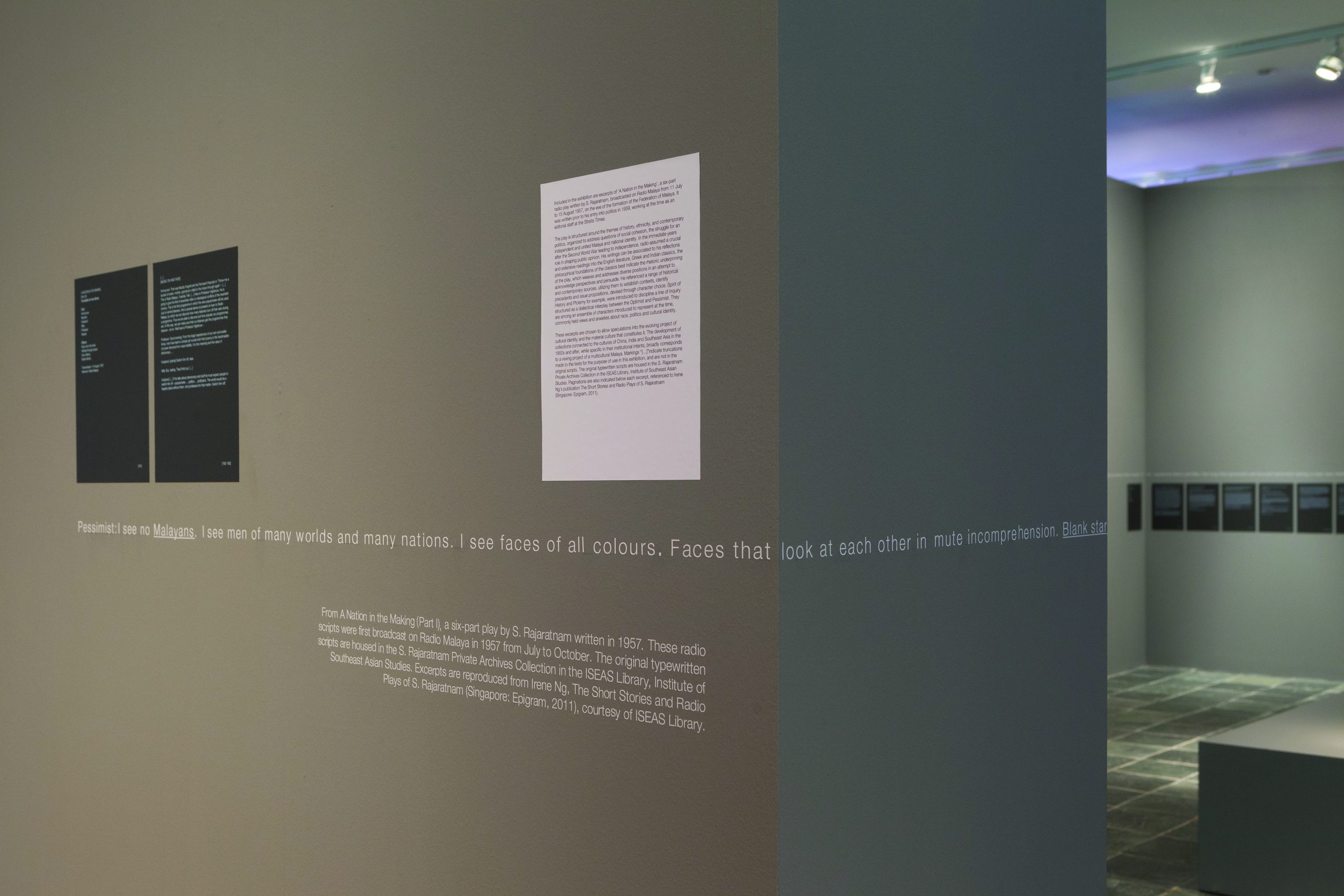

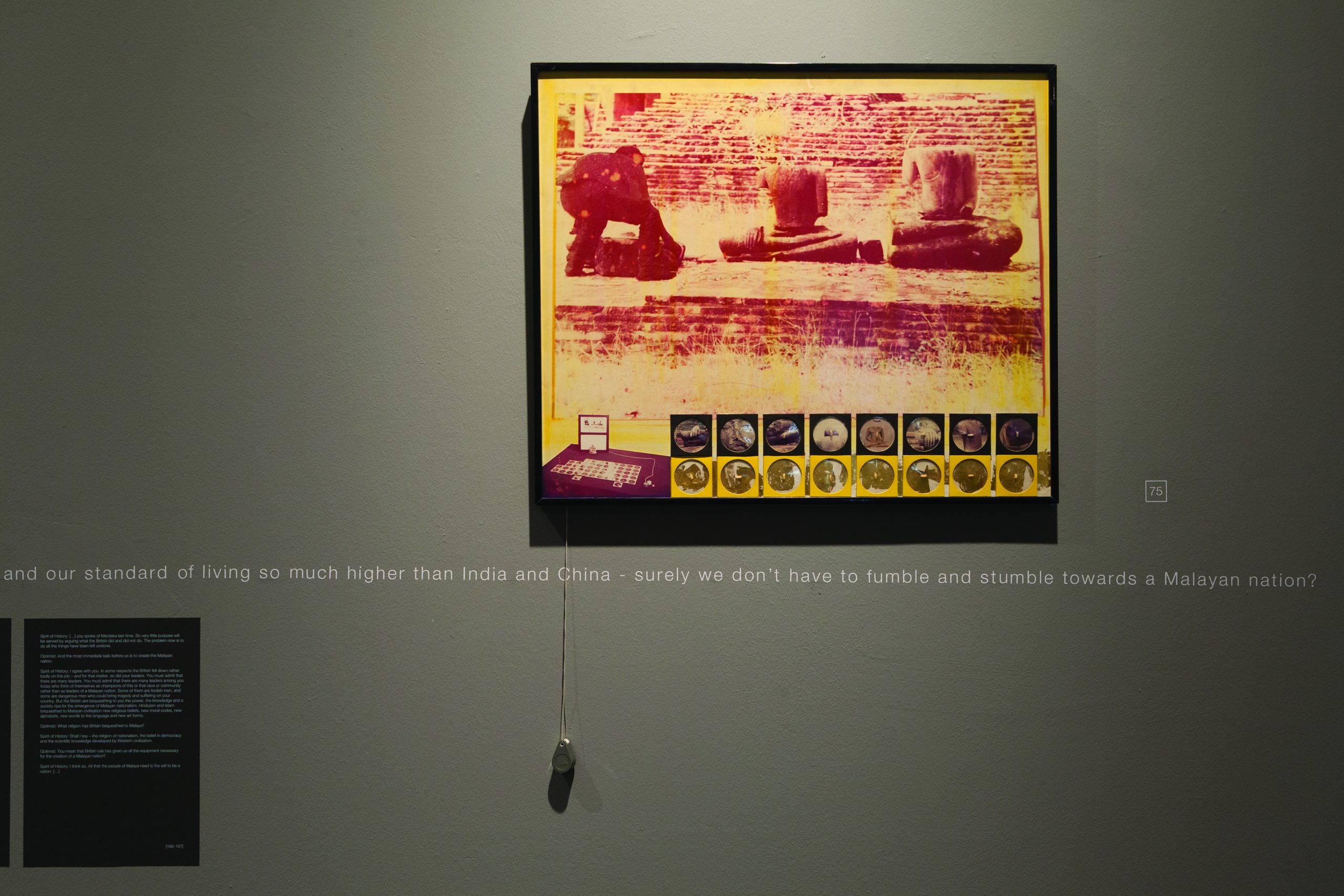

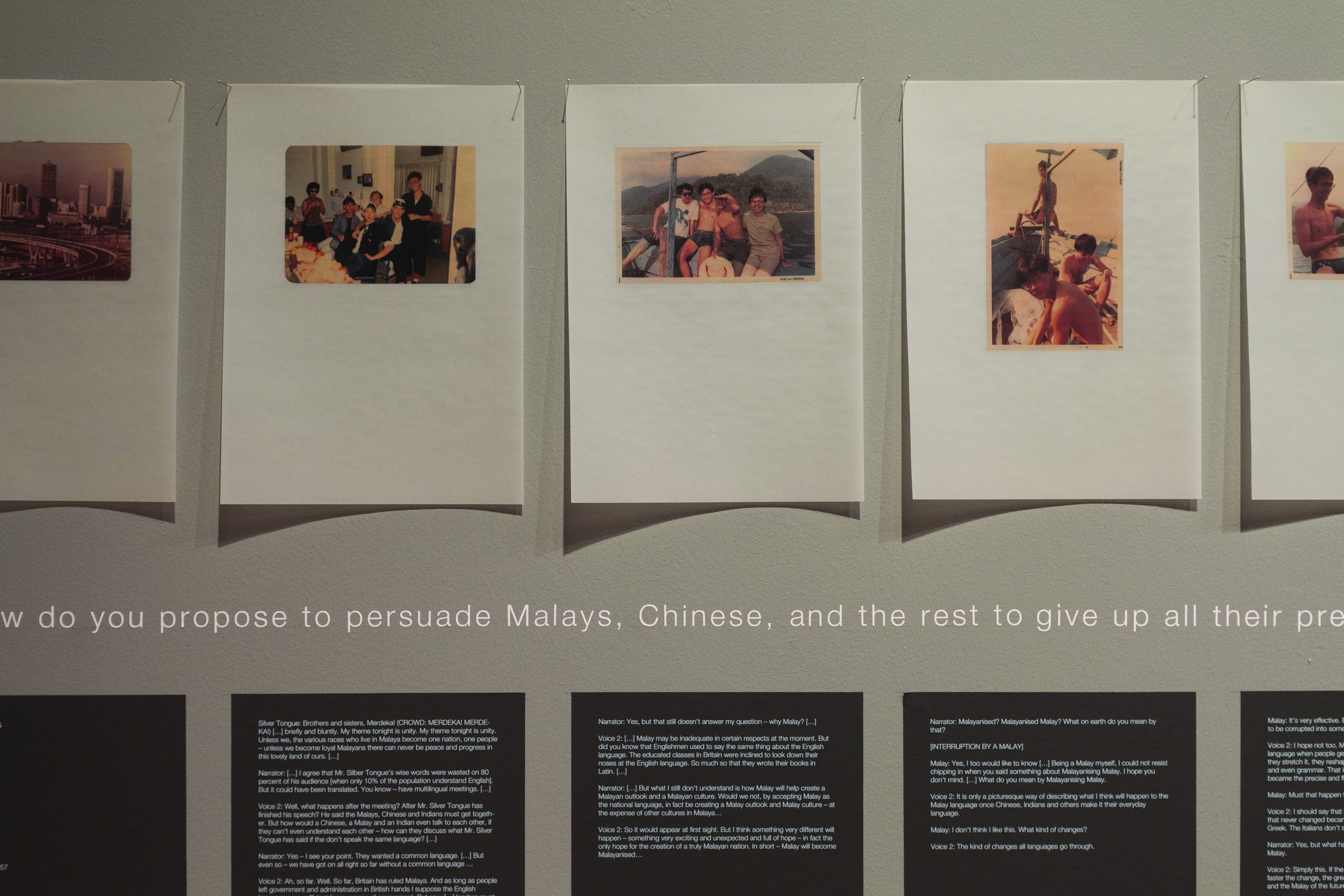

Exhibition view, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art, 2017.

Curated by Ahmad Mashadi and Siddharta Perez.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

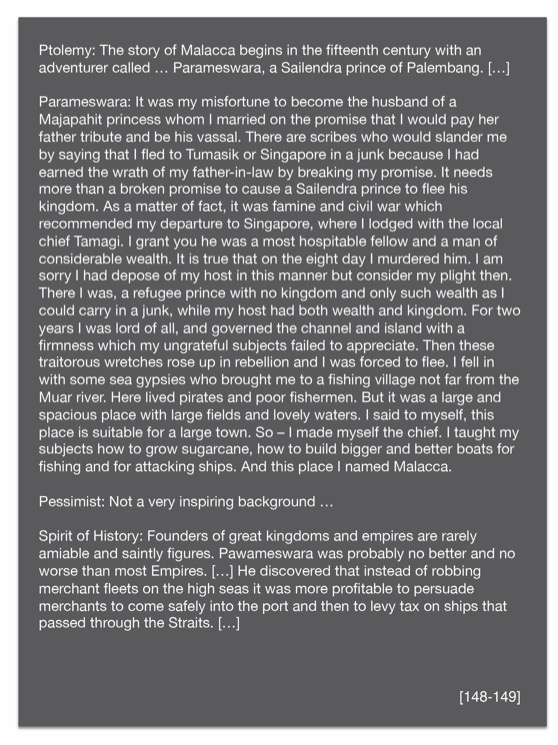

Fragments, texts reproduced from A Nation in the Making (Part IV),

a radio play by S. Rajaratnam, 1957.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Exhibition view, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art, 2017.

Image features various figure drawings at Clifford Pier in the

late 1960s and early 1970s by Harry Chin Chun Wah.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Exhibition view, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art, 2017.

Image features Koh Nguang How’s photo-assemblage Untitled (1994)

based on his trip to a temple complex in Thailand.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Exhibition view of fragments from a former Muslim shrine that once stood on the banks of the Kallang

River, The Sufi and the Bearded Man: Re-membering a Keramat in Contemporary Singapore, 2011.

Curated by Shabbir Hussein Mustafa, Nurul Huda Rashid and Teren Sevea.

It was re-presented in “There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

My name? Surely you already have my name. Okay, Eric [Ronald] Alfred [b. 1931] speaking, former, founder curator of Maritime Museum that was set up in Sentosa in the 1970s. It’s been quite sometime. I can’t recall most of the things that were happening. You have to prompt me along the way so that I can give you a meaningful interview. It there is a particular time or period? Well, I did an honours degree in zoology at the University of Malaya. It was known as the University of Malaya at that time as it was the only one university in the whole of Malaysia and Singapore. So I gained an admission there and I completed an honours degree in zoology, and having done that, … while I was a student I was introduced by one of my lecturers to the Raffles Museum as it was known. I was asked to go there and consult some of the publications. That was when I met Michael [Wilmer Forbes] Tweedy — he was the director – and my future boss Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, I didn’t know it at that time. But that was long time ago, and I was encouraged by Michael Tweedy to apply for a job when I graduated, which I did. I applied [for] the job as curator of zoology of the Raffles Museum [in 1957]. I spent, something like twelve years there, doing things diligently. I was in charge of this huge zoological collection. This was a large collection which anti-dated me for more than a hundred years. Collections not just of specimens but also quite a wonderful library, [including] 18th century publications which made them valuable if anybody wanted to research. I took care of all of these, and there were researchers from the university or from overseas wanting to see specimens, consult publications. As a consequence, I became very knowledgeable on many subjects, not because I was particularly intelligent but because of frequent associations with these … So I get to know quite a lot about things that are not quite zoology including … that’s how I picked up my knowledge about prahus and boats, and eventually ventured into the maritime field. [Initiated around 1969 and publicly announced in 1972] The Port of Singapore Authority [PSA, now Maritime Port Authority of Singapore] was thinking of establishing a maritime museum. The chairman himself approached me, a personal friend. He said, ‘hey, can I buy you lunch’ or something like that. He showed me the whole of PSA and he said ‘we want to set up a maritime museum on Sentosa, how about it?’ So I said I’ll have a go.!

00:00 My Name?

Extract, transcriptions of Charles Lim’s interview with Eric Alfred,

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

I was working at the Maritime Museum minding my own business when somebody from PSA [came], “Hey Eric, we found this guy milling around, he came to PSA looking for a job, we can’t fit him anywhere and see what he can do? He can’t even speak good Malay.” Then I said ok, let me try [him] out. Aley [bin Amat] turned out to be a boatmaker who had lived on Pulau Semakau [having moved from Riau Islands, and later Pulau Bukom]. He was not only a boat maker but he repaired all the prahus of all the people in Singapore. He was very well known. I put him on the staff [in 1976]. [That was] the only way to get him on, so he became a member of the Museum staff. Then, quite by accident, the Penghulu [village head] of Pulau Brani was a boat repairer, so I also put him on the staff. So I had two boat people on the staff. So I got hold of them as carpenters. And this boat building shed was built by Ahamad [bin Osman], the boat repairer. We built a contemporary Malay house on two-thirds scale. It looked like the real size but tit was two-thirds scale, people could go in and stand there and take photographs. It was down in the gallery, a watercraft gallery. He [Aley] was an excellent craftsman, rule of thumb, and he can produce very good Malay prahus, One day to test him, I asked him to build a, you know, dragon boat; they were doing dragon boat racing in Singapore. I said, “Can you make this?”, and he said “Boleh [can]”. [A] month later, he said “Sudah [ready]”, a full sized dragon boat. I don’t know where to put it, but we never put it into the water. It was built by Aley, quite a versatile fellow. He probably passed away, but he left a legacy of a collection of prahus. There is a photograph he shows, a kolek Johor [Johore boat] he made. That is the story of Aley and Ahamad, Ahamad the Penghulu of Pulau Brani. He was also the Bilal of the mosque, so his word is quite important you know.

21:26 Aley and Ahamad

Extract, transcriptions of Charles Lim’s interview with Eric Alfred,

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Charles Lim’s interview with Eric Alfred, originally presented in

In Search of Raffles’ Light: An Art Project with Charles Lim, 2013

(curated by Shabbir Hussein Mustafa), re-presented in

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Fragment, “Raffles’ instructions to the Land Allotment

Committee and the Town Committee, November 4th 1822,”

reproduced in full in An Anecdotal History of Old Times in

Singapore, From the Foundation of the Settlement under the

Honourable the East India Company on February 6th, 1819,

to the transfer to the Colonial Office as part of the Colonial

Possessions of the Crown on April 1st, 1867 by Charles Burton

Buckley (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984) p. 81-87.

Exhibition view, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art, 2017.

Image includes paintings by amateur artist, merchant and colonial administrator

Charles Dyce, completed during his stay in Singapore during mid-19th century.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum.

Exhibition view, “When you get closer to the heart, you may find cracks…”

Stories of Wood by The Migrant Ecologies Project, 2014.

Curated by Kenneth Tay and Jason Wee of Grey Projects,

featuring artists Lucy Davis, Shannon Lee Castleman and Kee Ya Ting.

It was re-presented in “There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

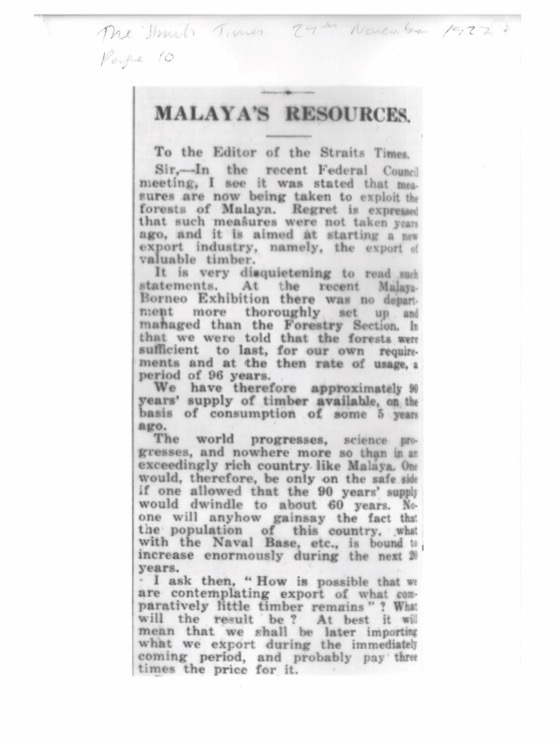

The Straits Times, 29th November 1927,

from “When you get closer to the heart, you may find cracks…”

Stories of Wood by The Migrant Ecologies Project re-presented in

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Southern Islands were inhabited with various people, you know. I used to visit them: Semakau, there was a school on Semakau [opened in 1951]. The kids used to come around, solid building. Pulau Seking was another Island, inhabited. Most of the islands were inhabited. I used to visit them regularly to see what was happening. Along the line I took lots and lots of photographs. Unfortunately I left them all with PSA. Whether they kept them or threw them away I do not know. I did not keep any unfortunately because they were done with PSA cameras. I had one of the technicians doing the photography. I knew many of these people would be resettled so I took photographs just for record. I don’t know what happened. I think it [the resettlement] more or less began after I was there, then they have a programme to work on resettling the people. As far as I know it began after I joined the Museum. I wasn’t involved in it. I was there on the sidelines watching it, other museum staff [were] involved in doing this. PSA had a huge team, those were the guys involved in liaising with HDB [Housing Development Board], getting flats, checking the people concerned, getting them resettled. This happened quite nicely I think. Of course there was one family who had no identity cards, don’t ask me how [that is so]. That was the problem: they had no ICs. They were kept for last, [but] eventually they were housed. They lived in Sentosa without identity cards. That’s the sort of situation which you have to use your brains a bit.

38:17 Vacating the Seas

Extract, transcriptions of Charles Lim’s interview with Eric Alfred,

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Exhibition view, “There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.

Image features a disassembled kolek, which formed part of Dennis Tan’s

investigations into boat-making in the Riau Islands.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

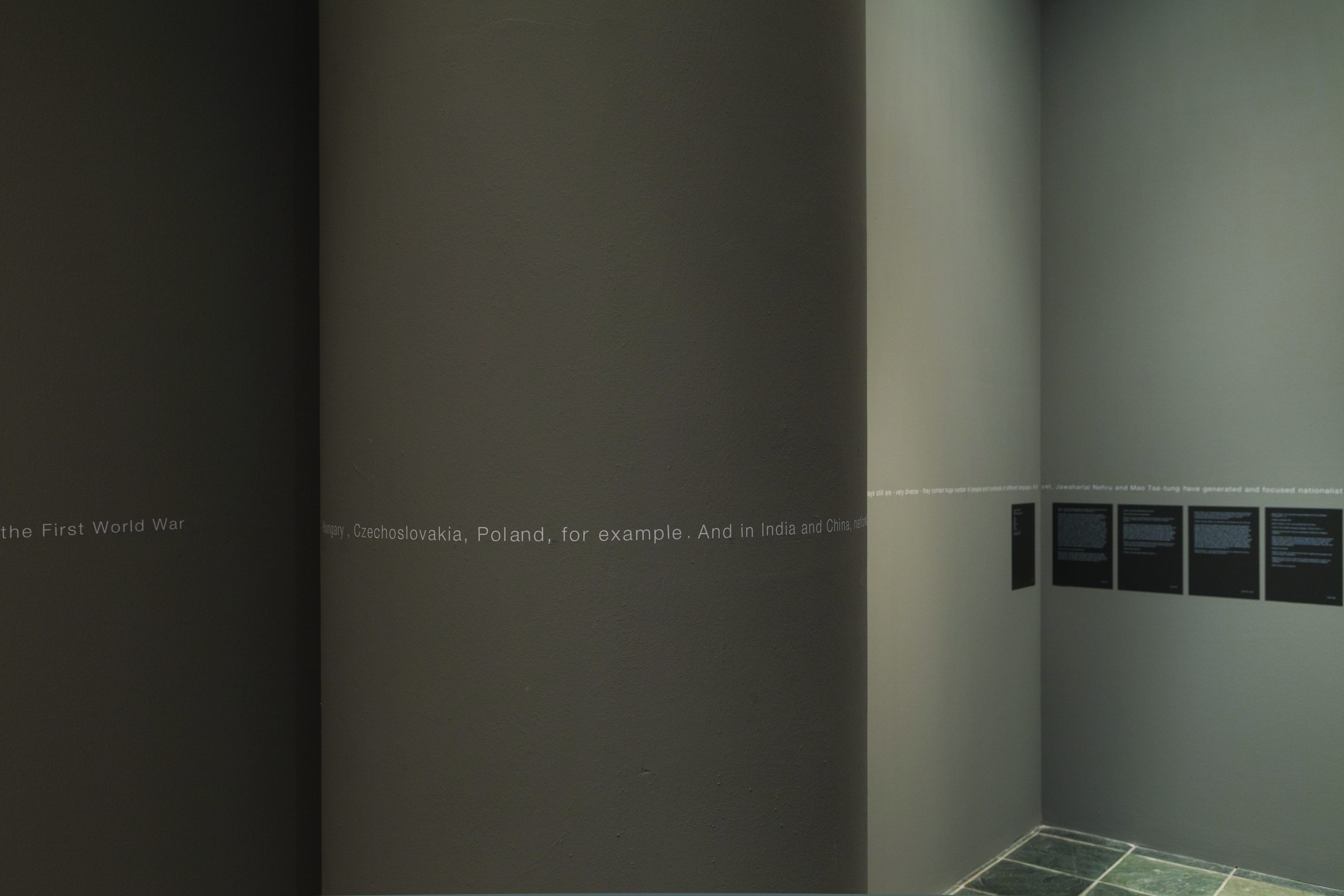

Excerpt of text on wall:

Pessimist: I see no Malayans. I see men of many worlds and many nations. I see faces of all colours. Faces that look at each other in mute incomprehension. Blank stares. Because they don’t understand each other. They don’t understand each other’s religion. […]

Optimist: No. I’ll show you in a moment. But as I was saying – nationalism itself is a pretty new idea you know. New even in Europe.

Pessimist: Well?

Optimist: Loyalty to nation was a feeling which people cultivated only during the French Revolution. The nation state is very new in the history of the world. […] it didn’t become a force in Asia till the thirties. India and China were—and in many ways still are—very diverse – they contain huge numbers of people and hundreds of different languages. And yet, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mao Tse-tung have generated and focussed nationalist feelings in their own lifetime. Now we are so much smaller, and our standard of living so much higher than India and China – surely we don’t have to fumble and stumble towards a Malayan nation?

Pessimist: But what about the deep-seated race consciousness here? How do you propose to persuade Malays, Chinese, and the rest to give up all their prejudices and preferences and adopt what you call ‘Malayan consciousness’?

Optimist: Ah. Now I think we are getting somewhere. […]

From A Nation in the Making (Part I),

a radio play by S. Rajaratnam, 1957.

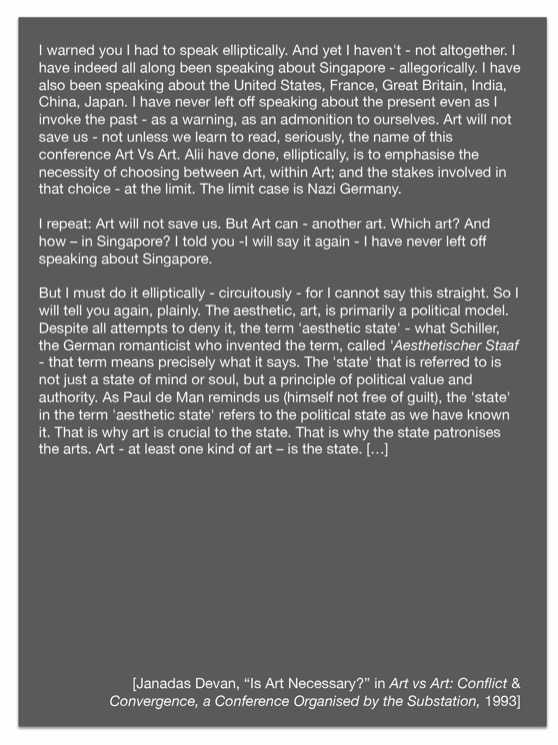

Janadas Devan, “Is Art Necessary?” in Art vs Art: Conflict & Convergence,

a conference organised by the Substation, 1993.

Exhibition view, Radio Malaya: Abridged Conversations About Art, 2017.

Image features reproductions of Jimmy Ong’s personal collection of photographs from the

late 1980s to early 1990s, entry-points into the formative.

Photo: Geraldine Kang © NUS Museum

Working in the PSA had opened my eyes to many things I would never have seen. I saw the shipping revolution: the first container ship that arrived, and subsequently all the normal types of ships. In the early days ships have funnels in between at the top and they gave out smoke. They were of mixed [use]. They carry cargo and passengers, and those ships gradually vanished. These well known shipping lines like Blue Funnel and [?], they have all gone out of the picture, and eventually you have new shipping lines like the Neptune Orient Lines coming up, huge ships being built, supertankers. I saw them coming in one by one. I saw the shipping revolution, it happened right in front of me. Working in PSA did broaden my knowledge. You have got to keep your wits about it, you take things for granted if you don’t look. Singapore initially was well tuned, functioning as an entrepot port, that means it accepted all the little ships, small steamers from the little ports from around the Malay Peninsula, Indonesia, dropping their goods, unloading their cargo and the twakows [bumboats] coming up the Singapore river, having [their cargo] sorted out there, and eventually going out again, being shipped out on ships to Europe and Japan [belonging to] big shipping companies like the Nippon Yusen Kaisha, Lloyd Triestino. These were the big shipping companies that were coming in you see. Then you have the first container ships, all the passenger-cargo ships became redundant, you saw them vanishing one by one, all the little coastal ships vanished. Eventually all you did see are huge rankers out there, still there, huge supertankers, small sized tankers, you go to [today’s] Marina South and you stand near the jetty and look. You can see a whole lot of workboats. These are boats that either carry crew, cargo out to the oilrigs, Then you see other types of specialized vessels, just working anchorage. You don’t see warships there. There is a cable ship there, ASEAN Cableship. They still use underground cables for communications. What else do you see? That’s about it.

56:27 Revolution at Sea

Extract, transcriptions of Charles Lim’s interview with Eric Alfred,

“There are too many episodes of people coming here …,” 2016.