ISSUE editor Venka Purushothaman in conversation with artists Rirkrit Tiravanija, Navin Rawanchaikul, Som Supaparinya and Milenko Prvački.

This conversation occurred in Chiang Mai, Thailand, on 20 and 21 January 2025. The discussion aims to be as close as possible to the participants’ comments within their vernacular expressions and has been edited for clarity where needed. The original transcription was considerably longer; the present form is a focussed rendition.

Relating to Service

Venka Purushothaman

Today, there is a pronounced concern around service—the idea of being of service to others and to the community around us. An increasingly agitated public is calling into question the idea of public service, as seen in the political landscape.

What does to be of service mean? We want to understand artists’ perspectives on service and their understanding of the effect and affect of art on the public. This inquiry lays the basis for our conversation to understand your practice and how you have seen your work engage with the different communities that you might have been interested in engaging or new communities that might have emerged as a response to your work. We also want to understand what’s going on in Thailand, in terms of culture and art practices, and how things are shifting here. Do changes influence how you practice or make art, whether politics or technology? For example, there is artificial intelligence (AI) and it is pointless to fight it.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

That’s a service. Actually, AI is a good starting point, because I am talking to my students at Columbia University who are, you know, in that space.

I propose to them that we try to make a lazy AI, right? I want them to find a way to make an AI who refuses to be all the AI that everyone wants—in a way, that’s what the artist is, right? Always, maybe, in a way, doing things that contrast with the rest of society. In a way, we understand ourselves because we have the other, which is different from us. And the other, in this case, would be a lazy AI, you know. And what would the lazy AI be? Because, of course, it has to be or do something right. There has to be some purpose, but the purpose would be to be lazy. But how would the intelligence, or a thing that accumulates information, you know, how does that become lazy? But of course, it can accumulate and do the opposite of what everyone expects. Because one day, when there are too many AIs, you need a lazy one to stop them all, like a virus in a way.

Milenko Prvački

Knowing you for such a long time and hearing you talk about artificial intelligence and the art of being lazy—I love these terms. It’s subversive, but you talk about it pragmatically so as to mean to spoil something—this is a very artistic approach.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

For me, the idea of service seems like a transactional thing, which is always a mistake that the West makes about my work. I do not make transactional work, but people tend to think that is what I do since I give things away or make food for others. They (the West) think it is a kind of exchange of service. For me, it is a common everyday thing in my daily life with my brothers and sisters, friends, and cousins. This, for me, has been the gap of understanding and misunderstanding of what I’m trying to do and what they understand. I try to vaguely speak about this in a kind of Buddhist philosophical stance, which is, I do things because I believe the reason for my existence is different from theirs, because we are different.

I’ve always said, you know, what I do is really, really simple. I do what I do every day. And it’s not about and our existence here, at least in Thai culture, is not transactional like that.

To me, service is a kind of capitalistic understanding of exchange in a certain way, which I try to destroy by layers and ways to model our relationship to the world and, particularly, our growth.

But there’s really a big gap in understanding. Because everybody still approaches everything (art) through the object, even if we say it’s relational, they still approach it as an object. They don’t understand what relationality is because they still focus on things that are in the room. They still try to preserve the things in the room. They try to maintain them, that you know, when it’s really nothing you can keep or hold on to. It’s just like a moment of us sitting together, whether three hours or five minutes, that’s it, and the value of that is what that is. And you know that’s just – but it’s very hard for people to understand the value of that.

I just had a retrospective, A Lot of People, in MoMA (USA) this past year. And you know, all they did was try to arrange the things that were, you know, sitting there, and I keep saying, you know, it’s not about you having to use it. You can’t just arrange it as if it were that moment when it happened, right?

Venka Purushothaman

How did they respond to that?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Respond, yes. They put a plexiglass box over the thing.

Milenko Prvački

Resistance, resistance. It’s also because they want to preserve. They want to preserve, and that’s how they accept things. You want to change, and not many people are out of the quotidian of everyday understanding. Curators today especially want everything to be readable, clear, and justifiable.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

The right part of relational structures is experience. And when I do things, I want people to understand things through their own experience. It’s not that I want them to experience this, and then they understand. I want them to understand themselves through the experience, even if it’s not easy. The experience could be very simple. So, the experience of eating together, for many people, for us in Asia, is very normal. But for 1990s New York, it was strange for some reason. It was unique as they don’t think about sharing or being together like we do in Asia. Yet, we try to catch up with the West and always model everything we do on the West, and then we end up using their structure to determine what we should do.

In Thailand, when we start to paint on canvas, it’s like moving from the temple wall to a modern structure. And there is a difference, but we must understand why we’re doing that. Why do we take it off the temple wall and put it on a canvas? It’s, you know, a Western idea, like value, to have exchange—you can actually own it, objectify it, make value out of it, and it becomes property. So, this is the point where I try to destroy that idea of property in whatever way I can.

Then there’s the visual thing, or the idea that one is visual art. It’s visual because you’re looking at it.

And to say that, well, it’s not just about looking but about understanding what you’re looking at by your own experience. There was a small retrospective show I did where I showed nothing: just an empty museum. The museum organised a tour for a dozen people, and the docent would take them through this empty museum, and they would just narrate, stop at some empty spot, and narrate what they would be looking at.

Venka Purushothaman

Your insight into unpacking the way we should necessarily look at or experience art by bringing the public to an empty space is significant. You remind us that how we look at art or how we are trained to experience art, through infrastructure or an instrumentalised curatorial approach, needs to be revisited.

Jumping off some of the points Rirkrit has just spoken about in terms of appreciating the relationship between the public and your art, Navin, could you share your experience?

Stories and Experiences

Navin Rawanchaikul

About 30 years ago, in 1995, I visited Rirkrit in New York for the first time. I mean, we, in Thailand, knew his name. Working as an artist, I was out of university for one or two years, and I brought a VHS videotape to show him what we did in Chiang Mai. As a student, before the internet, we came across his name in books and magazines. So, I went to show him what we did in Chiang Mai.

Around 1992, we, as art graduates from Chiang Mai University, started using found and existing spaces near temples and cemeteries. It was a way of finding what we could do when we didn’t have infrastructure or a gallery. We had one kind of university gallery, but it was not really for contemporary art.

But temples, you know, not just in Thailand but in Asia, are a kind of place where everything happens: education, morality, art, culture, everything. So, we use a temple for our art.

We used a public space to be very experimental in organising our art exhibition or festival. We got good and bad responses. Somebody called and complained. That time, I used my parents’ phone number and informed the state, explaining why we used a number of public spaces to show the art. We did it for three or four more years. Som, you were in the second or third, right?

Som Supaparinya

I have never participated in the festival. I was a first-year student at Chiang Mai University when the festival started.

Navin Rawanchaikul

We did for four or five years. We helped bring different artists to town and helped them produce the work. We grew from showing local Chiang Mai artists first and later more Southeast Asian, in a way.

We didn’t know each other, but when I met Rirkrit, I showed him the video. He said he would finally come to Thailand, and we could do something. At that time, I also had a project in Bangkok using a taxi as a gallery. I think he saw that, I remember, he knew what we did immediately.

So, when it came to expanding the possibilities of doing things in the public space, especially in Chiang Mai, we did not have the infrastructure but after 2000 I think it’s different. In Thailand, we have a new generation—they have galleries, Southeast Asian art market, China and everything you know.

But back to my practice, I have an interest in history, particularly local history. I work on my personal history and also work with local historians. I look back at my own Indian roots and have done a number of projects and reports on the Indian diaspora, including one in Singapore. For me, it’s a personal interest to also keep that record.

I use art as a way of recording and showing. But also, for me, it is a way of being part of my ancestry. For me, it is a kind of service.

It’s funny, but sometimes if someone’s parent dies, they call me to ask how their parents are connected or their ancestry. You know, like a historical record. It’s a little thing that I can do. During COVID, when we could not travel, I did a project on my story of my professor, late artist Montīen Boonma, trying to connect back 30 years ago when we started our project together. And it’s not just about the art, but also, you know, the historic temples. I try to bridge contemporary art and local history.

Venka Purushothaman

You talked about the relational dimension of art practice and the spaces of engagement, whether it’s a taxi, a cemetery or a temple. How has the art community responded when you move out of the white gallery box into the community?

Left to right: Milenko, Navin, Rirkrit, Som with Venka in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Courtesy of LASALLE College of the Arts.

Navin Rawanchaikul

When I was involved in the Chiang Mai Social Installation Festival, I did a project with the local community, interviewing them and capturing stories that transformed into artwork. The process was very important for me because it allowed me to meet people and spend time with them. The final artwork may be just a record, but spending time with people and learning about them is important—their story. And again, for me, what I try to do is keep that record. And you know, I mean that voice, how we can transfer everything, preserve, and maybe they may not even know what is called art.

For the local community, they think art is culture. They don’t really have the term contemporary art. It’s not a bother for me, as long as I still have this kind of invention or my way of presenting their stories. The local community, when they see it, will understand that it is okay. It is similar to when your mother looks at your work—they see the work that you do and it connects with them.

And for me, it’s the small communities that are more interesting than talking about the global moment—that I can spend time with one person or one community, and try to live or capture that experience. In my duty or role as an artist, how I can preserve and transfer that moment into so-called art or whatever media, but it’s the moment.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

To the question you ask, Venka, on the art community’s response when art moves from the gallery to the community, I would say the West doesn’t understand this kind of relational structure. Look at what happened at Documenta 15. The West doesn’t know art outside a white cube, where it can be contained. When it is not contained, it is chaos, and to them, it becomes scary. They don’t understand that their way of making art is, first of all, over.

Their way of thinking about artists is like prehistory, while the rest of the world’s understanding of art and life is completely different. They don’t understand that. They don’t know how to look at and contextualise it, so I think that’s the problem of the West. For me, having seen Documenta, standing at the front gate of the city, and you know, people are doing stuff and I’m doing what I’m doing, I watch people and it is interesting to see the response, or the non-response.

Even in a place like Singapore, people understand art as a certain kind of structure. Here in Thailand, people don’t understand it and have very different ideas about how to judge it. They don’t judge it. They want to know and understand their experience. They wouldn’t object to it. They wouldn’t question whether it’s art or what you know. That is a very free and open thing. Unlike the West, many people know critical theory and would want you to know, but not understand, because they don’t understand.

Navin Rawanchaikul

When people move from mural to canvas, you have to look at the history of education. Education makes a big difference, but we all took Western-style art education in Asia. But if you look at history in Asia, there are no borders between art and life, art and culture, and all depends on people’s local life.

Venka Purushothaman

Arts education is important, as much of Southeast Asia inherited a colonial arts educational model. It’s only through the work of artists that traditional learning paradigms came to the fore, having historically been built within communities of craftsmen and maker cultures that are deeply embedded as part of everyday life.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

In the Thai model, half of the people who went to art school were trained as craftspeople. The Italian sculptor (Corrado Feroci) invented modern Thai art when he started teaching, and you can see the aristocrats becoming artists, just as craftspeople became artists. This moment for us in Thailand should really be thought out and examined as to why we even made art.

It is important to understand the shift from craftspeople, remaining anonymous, to the emergence of a kind of auteur. You know, this moment is significant and it would make a big difference for us internally in Thailand to understand the terms of what we can do to move forward with our own art.

Because we model the West and just transfer it from wall to canvas, we are just making souvenirs, you know. For me, to make art is always to question the model; younger artists today have also learned other models. For me, my model is Fluxus, which to me is rather Asian, by a kind of mental aptitude, a desire to equate life and art. That’s a West looking at the East model. Navin’s ‘social installations’ festivals are about the material and the social relationships. You know, we have history, and we need to reinvent it. You have to bloody write it out, play it out, and show them (the West) that we have been here, like, 2000 years before you even thought that.

Milenko Prvački

You can apply methods from the West, but you can’t become someone else. And you can’t avoid the necessity of expressing whatever you are, your history, your culture.

Venka Purushothaman

I want to return to education because I think it’s an important part of how we also impact our mindset around the understanding of art and its service.

Both of you have spoken very richly about how art works quite intuitively with its respective communities. I want to ask Som Supaparinya to share her practice and respond to the conversation.

Knowledge Sharing

Som Supaparinya

My practice… I studied at Chiang Mai University, and I say that I was a first-year student during the Chiang Mai social installation festival. During my time as a student, I experienced a lot of what was going on around me, not only in the classroom, but I saw a lot of activities outside the classroom, something extraordinary, more than what we learned in the class.

It was kind of a good experience for me. But I didn’t create a lot of work out of the techniques that I learned in school, maybe only in my final years. I experimented with other techniques outside the class. I was lucky because the school focussed only on painting, sculpture, printmaking, and some photography. But the department was quite open to me doing other objects and techniques.

I could learn by myself because it’s not in-class—some installation, some conceptual works and in almost the last two years, I saw myself consuming a lot of media like radio and television. I watched a lot of films and felt that kind of technique is also part of my life. It was a big part of my life. It was not a small part, because I was obsessed with that kind of thing. I started to use that technique for my work, and I needed to learn by myself, because it’s not in-class.

In the beginning, some teachers were against the work I was doing, as it was not what they expected. But some were open to that. It doesn’t matter to me as I go with what I want to do and the direction I want to take. But I’m not against the teachers either. It was too new for them. If it was something they don’t like or something I was experimenting with, I try to assist them. I can try bridging the gap between us so they themselves can be open. I try to help them open themselves to understand my work. Even my friends in the class, who didn’t get it because it’s too conceptual or nothing beautiful, I say it is okay, you don’t like it, but it is a different way from what you are doing.

It’s more like a process, a way of thinking.

That’s how I start when people don’t understand my work. I still have that way of doing things. When people don’t understand my work, or even when they hate it or say they don’t understand it.

This approach continues for me, and I hope it’s worth the education. I want to offer a kind of knowledge, a way of thinking, or direction different from what one expects.

Then after, I met Rirkrit and got to know him. He spent a lot of time around the school. I didn’t understand his practice, but as students, we knew him as the artist who cooked some food for us.

One day, he gave a talk. I went to listen. In the beginning, my friend and I did not understand him, and we were a bit against him since a lot of lecturers say lots of good things about him, but we didn’t get it. I overcame my stupid idea and went to listen to his talk, and then it started to make sense when he explained the whole thing.

During my final graduation work, I showed some of my multi-channel video works, some live performances by musicians, and some paintings. After graduation, we had a one-day, temporary group show at a railway station. Navin and Rirkrit were also participating artists. We experimented with the specific space. It was very interesting and very fun. I learned a lot from there and started to do site-specific works from then on. I used 60 rooms of the railway station hotel to create a type of live performance with many musicians.

After this, I wanted to learn more techniques that were not available in Thailand. I want to learn about media arts, but I had no idea what media arts programmes were available in the world.

I met a German professor who encouraged me to look into studying in Germany. I applied to many schools, not knowing how to call my practice. Rirkrit knew a little about my practice and started to describe it. He wrote a recommendation letter, and with that, I applied and ended up in Leipzig. This was my first time abroad, and I had no idea what East Germany looked like. This kind of big exploration for my life was totally new.

So I learned. My first class was not video art, but web art, just when web and internet art started emerging. It was too complicated for me because you need to learn a lot of programming and writing. Then I ended up in video art, which suited me—how to say, what I liked and also the way that I want to use the art, which is about time, capturing time, because I am interested in the changes in society, landscapes and many things. I focussed on that, and until now, I have mostly used that technique .

To me, my own art practice is often separated from other knowledge services that I give to the public directly.

But as an artist, I don’t separate myself from the art world. For example, the work I do with my collective is to provide information and to exchange knowledge services. But we never aim to produce any artwork together. Each of us produces artwork individually.

In Chiang Mai, beginning maybe in 2013, we (as collectives) began creating art maps to know what the art community in Chiang Mai looked like. And not only that, we all wanted to share that information with whoever comes to Chiang Mai and wants to see Chiang Mai or experience the art community, art space, or exhibition in Chiang Mai.

They can look at the map and go directly there.

It is a public service with the information that we want to provide. But we never created any artwork together. We have an individual interest in our artwork. We worked with Thailand Creative and Design Centre (TCDC) because people saw the city as an art city once we started the art map. They used the information to create a festival, an art festival, and later, after that, we got a grant from the Japan Foundation to be its partner to make a small art space to create an expert exchange between artists in Southeast Asia and Japan. We invited artists, scholars, or whoever we thought was interesting to do some knowledge sharing or some practice—something we were missing in Chiang Mai.

But what is a good show? Can we create a lot of activities—which did not happen enough— with talks, knowledge sharing, and activities that would be useful to artists in Chiang Mai? Japan Foundation chose Chiang Mai because it is not the centre (Bangkok). We needed to create our own profile because the centre doesn’t give us anything. The main media especially is never in Chiang Mai. There are a lot of artists here and very active, but because the media is not covering it, it is not noticed or recorded, you know? So that’s why we started to do these kinds of knowledge projects, because it’s important. It is not part of the Thai art story, so we [need to] do it.

Openness and Being Open

Rirkrit Tiravanija

What Som is saying is interesting. Chiang Mai is the periphery. I prefer it. This is also important and all three of us, and many people, artists here are involved with a more communal structure that is of service to each other.

We formed a group. We have the Land Foundation, and my neighbour has a museum. But to me, it’s all part of our work. In the West, they don’t understand that. Let’s say they know you and they know you only through the museums. I’m doing many things I don’t claim as art. I don’t sit around saying this is art and I’m making this.

The last thing I want to do is think that what I’m doing in the world is art. And this is the thing. We don’t think that way. We do things with the community because that’s how we work. That’s how we again don’t think of art as an object we have to claim, name, or define, which is a very Western process of understanding. They don’t understand when you don’t define it. They don’t understand when you don’t have a goal or expectation.

Milenko Prvački

You can’t justify what you’re doing.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

That’s the thing that is very different. The value that we have in this kind of discussion is not to not be defined. In fact, everything we do could be art. I could just be making pad thai noodles on the side of the road for the rest of my life. But the way I do it, everyone has company.

Venka Purushothaman

You talked about people’s struggle to understand your work and process. They are struggling because they have all these structures from which they seek to appreciate your work. It prevents them.

The work of all three of you calls for an open space for engagement. Our understanding of being open in Southeast Asia is quite different from the understanding of being open in the Western context, even though the concept of the ‘open’ has been theorised extensively, especially in anthropology. The moment you work within the community or a communal space, the anthropological lens immediately kicks in, alright, without the lived experience or the experience the public has. Openness seems to be construed to lead to confusion, which we saw in Documenta. But interestingly, it was not the experience of that openness that functioned, but the obsession with the object that triggered controversy. So, I’m kind of interested in the struggle of the ‘open’.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

This is my generation of artists questioning authorship and rights, which has already happened in previous generations. It’s a post-colonial question: Who is calling and naming what? Who is writing their name to? The idea of appropriation, appropriated art, is ongoing.

I mean, those things were there. The question, you know, should not be a question anymore about who makes the art, because the art is just an idea. I question how we even look at an object. Even conceptual art ends up becoming an object. Because they need to hold on to something material, be it a sheet of paper that says, “This is conceptual art;” they do still want that paper.

Venka Purushothaman

What’s powerful is that you empower people through your practice to be who they are, something that no longer happens in museums and galleries.

The Future of Museums

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Not anymore, not anymore. That’s right. I mean, museums. There are not the same kinds of experiences that the Museum of Modern Art used to have. You know, the museum itself changed, and they changed from being a place of art to a place of value. It was a place where you could experience different ideas, and now it’s just different values of things—that’s become part of the problem.

Venka Purushothaman

Or even the biennales.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Well, biennales have closed themselves off— to become more regulated.

Milenko Prvački

To name, to classify, to put on shelf has become a necessity. Just as Som said about categorising her art practice, many museums don’t know where to put it or how to name it. If we, as artists, make a mistake, there’s no victim, but they’re afraid they will be victims because everything is so organised. See, every museum has a section for kids. It’s like kindergarten. It’s wrong, they don’t learn anything. Artists are no longer going to museums; there’s nothing for them.

Navin Rawanchaikul

The role of the museum has changed over time. Museums are strong in the Western context. In Asia, the local culture is the space, and there is no idea of a museum. In Thailand, we have a lot of national museums trying to preserve the artefacts, but they do not really connect.

Museums have to update if they want to continue to stand and be of service.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Navin does his work in public spaces. It’s like a museum show in the market, but he also does a museum show in a museum.

And I would say, that museums need to go out [of the museum space]. If they cannot, you know, they cannot ‘cook’ (a reference to his pad thai work).

Venka Purushothaman

What is the relevance of a museum today, then?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

I still think it’s a place of knowledge and understanding. It can have experiences, even though they tend to over-explain everything before you walk in. Museums are an archive. It is an encyclopedia. But it also needs to address itself and use itself as such.

Milenko Prvački

But it’s conditioned. I mean, you are right, but the time is different. The speed is different. You know that the changes in this world are not happening every 2000 years or 300 years. The museum has to deal with the speed of change and what it seeks to represent as a place of knowledge where we can learn.

Navin Rawanchaikul

The effect of the object is still relevant to help people connect to the present. But perhaps, without museums and galleries maybe there will be more freedom, just like Thailand 30 years ago yeah?

Som Supaparinya

Dry exhibitions, objects and no activity. The museum doesn’t allow us to interact. It seems a little bit strange to experience that big museum with an object that has no activity around it.

I was thinking, if you should want to do something in a museum, yet you can’t, because the museum will say: Oh, temperature has to be this; that it will activate the alarm; and all these kinds of things are limitations to if you want to get out of box.

Venka Purushothaman

Museums are still relevant in many ways, but they need to find their own space as centres for the transmission of knowledge. How do they do that? Of course, a lot more museums globally are getting more people doing research and writing, but there’s no transmission to the general public. It is only functioning to archive. Ultimately museums are there to inspire the public not just be a mere record keeper. That’s why it’s called a muse!

Education in the marketplace

Navin Rawanchaikul

The art market has also changed the perception of art. When I started out, we even didn’t think about selling work.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Yeah, we just do it.

Navin Rawanchaikul

We do it. But now, before you do something, your teacher or someone who has market experience will try to tell the student: “Okay, you have to use this kind of material to market your work.”

Today, art students are taught how to advertise, find clients, and manage themselves. Thinking about how to present the work, find a client, or network is good, but this is not about the content of the work.

Universities, as places of knowledge creation and contestation, are changing, as are arts institutions. I am interested in the value of an educational environment. They were safe spaces, but no longer are.

Seated left to right: Navin, Milenko, Som, Venka and Rirkrit in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

Courtesy of LASALLE College of the Arts.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

At least in the art world, that’s part of the problem. The idea of a safe space has become another thing. The institution is no longer about knowledge and exchange but a bureaucracy of safe spaces. As cultures change, institutions become overly protective of themselves, just as museums are no longer as open or experimental, or as a place where real art can be made without limitations. You know, because they’re all trying to keep within a safe space (from being sued).

Milenko Prvački

It is opposite to the role of artists and students in art. You know, we are teaching them to open doors and windows, fly, and take risks. But we behave more and more with rules and regulations. Everything is planned and done in advance. There are no surprises; it’s safe. It’s a world that I find is wrong for art.

Navin Rawanchaikul

When it comes to art school, an Italian man made a legacy here and played an instrumental role in the founding of Silpakorn University. When Chiang Mai University was founded about 60 years ago, it took almost 20 years to set up the art department.

Venka Purushothaman

How do artists negotiate that space where the weight of history and tradition are central?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Institutions are afraid. I have never gone through any of the systems here in Thailand. They have no idea who I am or what I am, which is also part of the mistake, because I’m a person who’s totally open to the old and the new. We have to look at those who make mural paintings on canvas and acknowledge that they are part of the history. It’s not something I’m against. I wouldn’t do it. But on the other end, they are afraid that I would come in and destroy all of that. I’m not interested in doing so. I’m interested in making a better system.

The reason I’m interested in coming to Chiang Mai, I would say, is that the school here is an alternative to Bangkok and much more interesting. So, I wanted to support that. And I have no interest in position, rank or name or money. I would do things for free if they would ask me properly. I did do lot for them even when they rejected me.

Som Supaparinya

As a student, the situation was quite free, and there were a lot of experimentation. The university was quite free. I choose to study painting, because it was the only department at that time that was open for me to do other techniques. It did not matter to them—a golden time for the department. But then they started to fix the curriculum.

Navin Rawanchaikul

By technique.

Som Supaparinya

They separate [the curriculum] by technique and you can’t cross to other techniques. And it’s very difficult. We should have more freedom. But we do not. The university has become a business and the government does not really help.

Navin Rawanchaikul

They [government] do not subsidise them anymore, or subsidise a little bit, so then the university has to make money. Would be good if this can be made clearer. What I mean is, less subsidies to the public universities lead to their being forced to make money.

Som Supaparinya

It’s very strange. It has changed a lot because of the political movement in Thailand in the past 20 years. A lot is happening, and the conservative way of controlling the university is getting stronger. Because of student movements, they need to control the university very strictly. They hire more and more conservative staff as Dean to lead to control. That’s how it has changed a lot in the Thai art community. There is conflict within the faculty.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

The institution no longer cares about the knowledge exchange; they care about money, and because of money, they have to make these very specific choices. University is a place of transaction. Therefore, they cannot let me call my class “How Not to Make Anything” because that is against the transaction. You see, I’m not, you know, to teach people not to make anything, is what. But like they, what are they going to get? You know, they’re not going to get anything if they don’t make anything, you know.

Venka Purushothaman

Jumping in, as a response to the over-institutionalisation and transactionalisation of arts education, I’m seeing this kind of informal pedagogy emerging, not in institutional places. Artist studios are becoming pedagogic sites, sites of really collective ways of thinking, new ways of engagement, and new ways of learning.

All of you referred to the structural system of ceramics, printmaking, painting and all of that, and the importance of freedom and what freedom meant. But what does freedom look like in the institutional system, other than being able to explore different things?

I’m interested in hearing about what kind of spaces of new learning are emerging, or spaces for unlearning. I use the example of the artist studio as a space.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

We have been trying to create new spaces. I don’t even want walls and I do not need walls to burn. I just need nothing. I just need an empty space and empty mind. It’s about the fact that there is a space, and if you want to use it, it’s there, it’s free, you know. And so, and if they don’t want to use it, you know, it’s there, it’s free, you know.

People who want to think and be artists will come and find the space. They will come because they want it and in order to find themselves. They need to sit and think and talk, listen to other people argue, and think, you know, really think.

Venka Purushothaman

In a market economy, the time from the art school to the museum space is very short. Time is truncated.

Navin Rawanchaikul

I think the art market is key, because in education, we never thought about how to sell. I mean, we don’t know how to sell the work. Of course, we want and need money to live, right?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

The time between making and showing is shorter because it has become about production—a product. And becoming a product means that there’s no critical space. There’s no critical time in space. The critical space now is whether people buy art or not. It’s not about whether the idea is interesting. Success and failure are based on sales.

Criticality now comes from lifestyle magazines—persons to watch! There is hype. What is hype? Hype is like a kind of transactional structure, which, you know, puts a value on something. Who knows if it’s actually real, right? So there is no criticality there. It’s just hype.

Hype makes a market. The market buys, and then, you know, they buy and buy, making a thing valuable. There is no real content there. There’s no real soul there. There’s no real artist there. It’s just technical, it’s just colourful, you know, whatever it’s the skin. And then it fails, and then the artist has failed, then the artists are stuck with, like, the fact that they fail in the market, and their work is like worth nothing, you know, so it’s not the value of the art at all.

Navin Rawanchaikul

They don’t teach about the market. Of course, you need to understand the market, but they don’t really teach as to what the market means and how you can work with it.

Som Supaparinya

My case may be different because I am always looking for funding to produce my work, my research, and all kinds of processes. I know that my work won’t sell, and most people are not really buying my work, so I know that, and I need to. That’s why I need to focus on where the money comes from that I can get support. I need to find funding all the time.

On Influences

Venka Purushothaman

I want to hear about your influences.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Well. I mean, you know, partly, of course, the work is also not just about me. It’s also about everyone else.

Navin Rawanchaikul

I enjoy working with communities. But when I work with people who are not art people, I would say, like, it’s difficult when you have to explain the process to them or get them information, but they really enjoy it. I mean, it’s that kind of direction, I would say, in Niigata, Japan. Also, I did a few projects, one in a very remote village. They didn’t know why this foreigner came and spent time interviewing them, but when they saw the work, they really appreciated it, and now they keep it. There are only 40 people living in that remote village.

Venka Purushothaman

That means the community owns the work.

Navin Rawanchaikul

They feel ownership.

Som Supaparinya

One Berlin residency I did, they did not pressure me to do anything. My one-year residency was only a research proposal, not to produce anything at all, no new work at all, which is okay.

Venka Purushothaman

It’s interesting how we try to look at the value. And I think all three examples actually removes you, removes you away from the art. It’s the work that speaks for itself. The process works for itself. It comes back to what you are saying, which is that the place of art in the lived experience starts to matter more. You know, rather than shifting away from the utopian object-centric, even though the art market focusses on that kind of an experience for a particular type of audience, there is that space where the lived experience matters, that temporality, you know, the time-based moment, whether it’s fixed or not.

I want to bring our conversation to a pause as these conversations will continue. Could you share your favourite followers, besides family, in terms of your practice? In terms of communities of people. For example, you talked about the people in the marketplace right who follow a particular work. Is that particular community that kind of, you never expected, but a group of people or an individual following your work, which you never anticipated? Have you had that kind of experience?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

My mother, you know. Once she knew what I was doing, she read everything not just about me about all my friends. She completely understood what I was doing and understood it through…I mean, the fact that, you know, I explained my relationship to how I grew up with my grandmother, and she completely understood that it was about, you know, yeah, being with other people, and, in a way, giving, but without that idea of, you know, transaction, right? And that could be giving knowledge, could be giving food, could be giving, you know, a smile. But it’s not about like getting anything back from it, you know. It’s just about how you exist in the world. That’s what you do.

So, I was also kind of, on the one hand, surprised, but on the other hand, you know, happy and understood, of course, because that’s our culture. She understood it because, you know, it’s not complicated, yeah.

Navin Rawanchaikul

Before my dad passed away, I spent more time close to him, and I also worked with him, but the effect on the history of my work is felt more in different communities. I always enjoy seeing how people react to my work. My uncle, my mother’s younger brother, just passed away. He convinced my mom to let me go to art school.

Som Supaparinya

My family does not support me to study art, but they have not stopped me; they couldn’t stop me—when I was 14 I told them that I wanted to study art.

From there, I just lived my own life and asked them for support. My sister studied art also, but she does not really know much about my work. But the good thing about her and her husband is that they helped me a lot when I needed to write a lot of essays in English because her husband is British and is good at writing. He helped me to edit, and they understood my work through that editing process.

On relationality and understanding

Venka Purushothaman

You have all have been written about quite extensively—always someone giving voice to who you are and what they think you are. Is there something that historians and writers have completely missed about you, and there is a part that never gets written?

Rirkrit Tiravanija

I don’t go and read these things or edit anything I say. There’s a book about me that has been translated into Thai. You know, it’s like a textbook about my work. I’ve never read it, but my feeling is that they don’t understand that I’m not from the West. They don’t understand me. I think differently. I am different, and I see the world very differently. And that difference is always something they don’t understand, and they’re incapable of writing about it.

Venka Purushothaman

It informs you of your relational setting that is central to you.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

But I don’t think they understand what relational means. Sometimes they call me the godfather of relational aesthetics. I disagree with the aesthetic part, because it’s not about aesthetics. It’s never been about aesthetics, a Western idea of how things are. I’m just interested in the relation, you know, and that they don’t understand, you know, they don’t, they haven’t really, and in that sense, because they don’t have a relation, I think.

Navin Rawanchaikul

For me, it’s more about how I see things and when I look back at my work, different generations will view it differently. I see this in my daughter, and I can pass on my ideas while also understanding that each person has a different view and way of their environment and life. It’s more about how you look and then look back again at your work and how you somehow understand yourself. That is how you make your art, why you make it. It is really for artists themselves to understand. To do the work, you must understand what it means.

My daughter wants to meet Rirkrit, a role model. She asks, “Can I eat his food? His food is art.”

You have to understand the artist by their life. This is something I see and try to convince myself of every morning. When I wake up, I need to know what I mean, say what I mean, what I feel and what I need to do.

Venka Purushothaman

So you feel that this part of the artist’s life is not discussed or does not emerge in art writings?

Navin Rawanchaikul

Either there are presumptions made, or it is ignored.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

I understand what he said. Writers and curators focus on the object as art, and they don’t focus on the bigger picture.

They don’t understand why Navin needs to go to the community and talk to people, and work with other people to make a representation of all these people, because the stories of things that people we don’t know. And, you know, I mean, they don’t understand. It’s Navin, that he can talk to all these people that he loves to speak to people that he could, you know, he can be in a community of strangers, and he will find his way to, like, drink and eat with them, you know, but that’s not going to be written because they are just looking at the object.

Milenko Prvački

Absolutely agree. They are looking for narratives that they can edit to recreate your work.

Som Supaparinya

Most writers focus on the final work itself and the subject. They are not interested in me as an artist. They focus on that particular area ignoring the source: that is, why I am making it or my environment. Different writers know different aspects of me and you cannot see the full spectrum of me in any one writing.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

Well, they are writing with their own perspective, their own interests and with their own knowledge. So, of course they will focus on only what they know.

Venka Purushothaman

Misunderstandings are also fundamental to a process of engagement.

Milenko Prvački

Writers and curators have their own agenda, and they unpack your work and pack it in their own way. But family is honest and curious.

Venka Purushothaman

We teach art history, but it is not seen as lived, that is, worked through with artists. Unfortunately, the limiting factor is retrograding history. So, we have to continuously puncture our way through to reach out to artists and their communities and bring a piece of yourself into that space.

Som Supaparinya

I have one story I like. A few years ago, I went to see the artist, Andy Goldsworthy. We talked a lot—our practice, his practice and my practice. And I also talked about how I produce my work in very challenging spaces like rivers. At the beginning, he was not really interested, just listened a little bit. And then at the end of the story,

I told him: “you know, I can’t swim, and I am scared of water.” He started to laugh, became interested because the way to see it is not only the process of the work and the product itself, but also to see what’s inside the artist and what drives me to work on it. It was a conversation that you don’t have in public.

Rirkrit Tiravanija

When I teach, or whenever I talk to younger artists, I don’t focus on what’s on the wall or what’s working. I focus more on what they’re thinking. So, I talk about thinking.

I like to know where they came from. I like to know what they eat. There is too much information about what they as artists want to make. But knowing them, I can see the problem that they’ve made. But, of course, I’m different. I mean, at Yale School of Art, they just only talk about what they see on the wall, you know. They won’t talk to you about how you are. And it’s two very different ways of thinking about art, you know.

Milenko Prvački

We all carry our history, we carry our geography, we carry our culture, we carry but it’s something very individual. It’s a kind of language, you know, language that we build up. But they’re (writers) not interested in this. They’re still talking about style, you know.

Venka Purushothaman

Because of what you all describe, we want to hear you and give voice (your voice) to this conversation. The artist’s voice is one of the most misunderstood spaces in the art world and in art practice itself.

Thank you for such a deep sharing. It gives me a small understanding of what is happening in different parts of your own practice and how it manifests itself in terms of the service that we do for ourselves, others, and society.

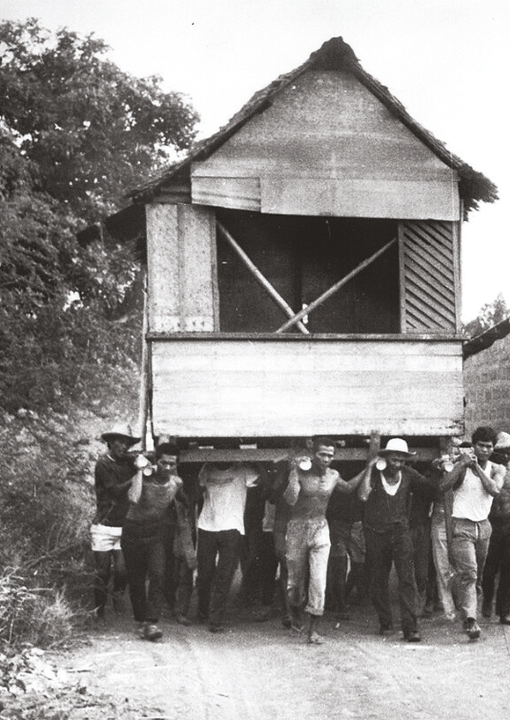

Navin Rawanchaikul, Blossom In The Middle Of The Heart (City), 1997

Reproduction of a mural painting by Khrua In Khong in collaboration with Sutthisak Phutararak

Navin Gallery Bangkok. Courtesy of Navin Production.

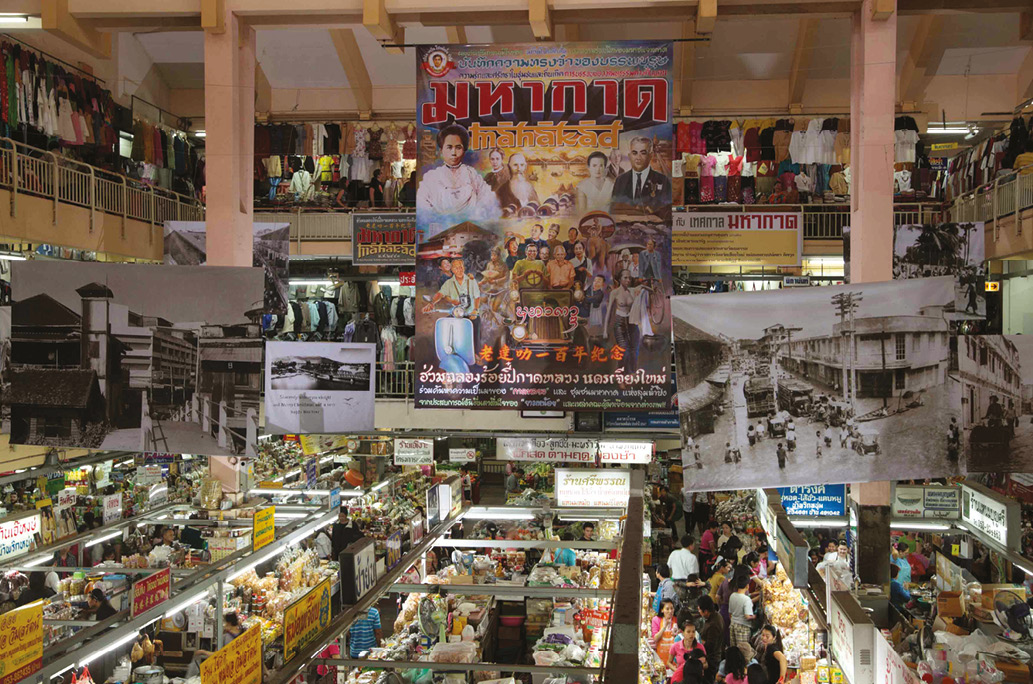

Navin Rawanchaikul, Māhākād (2010)

Chiang Mai, Thailand. Courtesy of Navin Production.

Navin Rawanchaikul, School of Akakura (2015)

Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, Akakura village

Tokamachi, Japan. Courtesy of Navin Production.

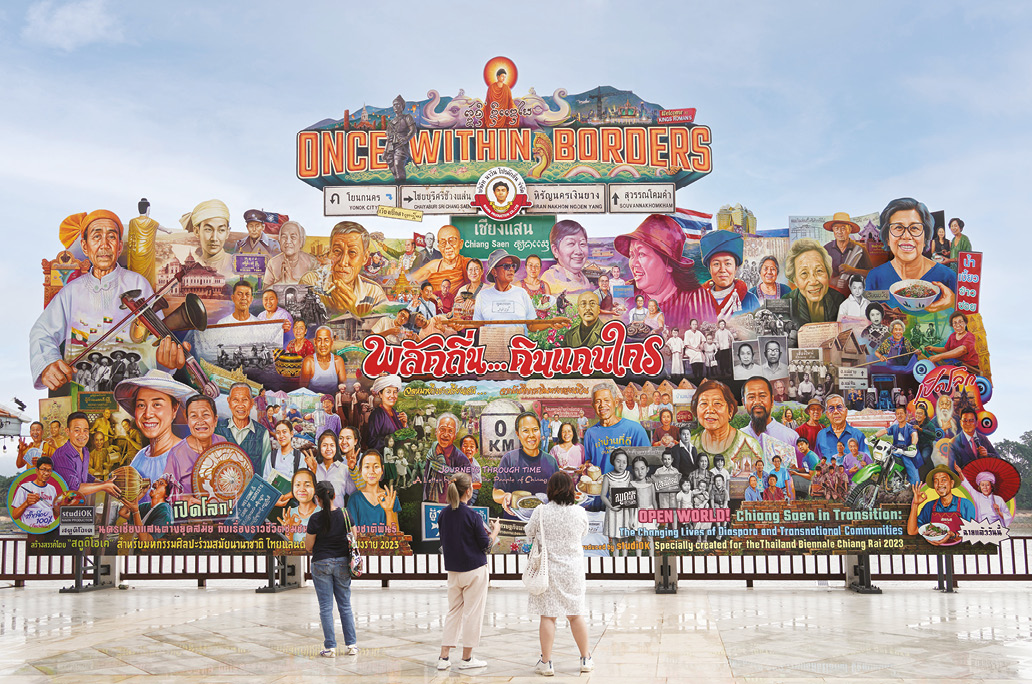

Navin Rawanchaikul, Once Within Borders (2023)

Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai 2023

Golden Triangle Viewpoint, Chiang Rai, Thailand. Courtesy of Navin Production.

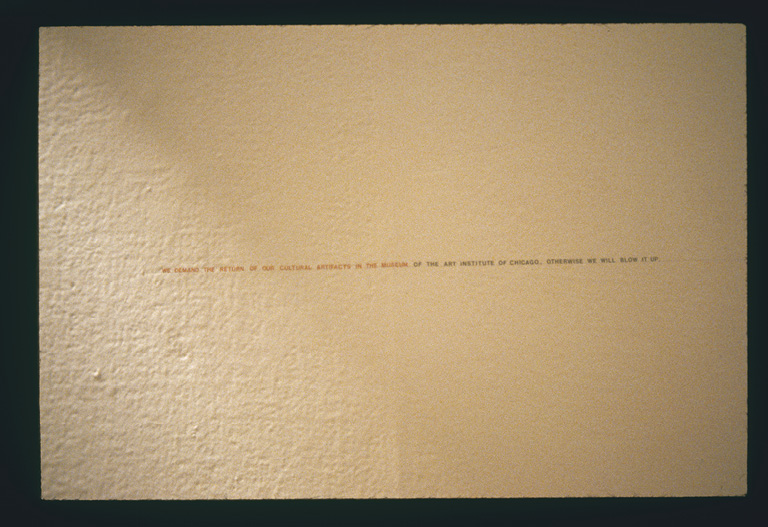

Rirkrit Tiravanija, untitled 1996 (tomorrow is another day). Courtesy of the artist.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, untitled 2002 (he promised). Courtesy of the artist.

Installation view: Rirkrit Tiranavija, Secession. Vienna, 2002.

Photograph by Matthias Hermann. Courtesy of the artist.

Som Supaparinya, The Rivers They Don’t See (แม่น้ำที่เขาไม่เห็น). Synchronised 2-channel video and other objects, 2014. Installation at National Gallery BKK, ©Kornkrit Jianpinidnan.

Som Supaparinya, When Need Moves the Earth. Synchronised 3-channel video, 2014.

Still from video, ©Som Supaparinya.

Som Supaparinya, White Shadows, 2012. Photo by Ded Chongmankong.