Philosophically considered, service is not a derivative act of compliance but a primordial modality of relational being—a movement that mediates between the unmanifest and the manifest, the Absolute and the contingent. It is a teleological arc, a vector of intentionality that does not originate in the ego but traverses it, directing it toward something beyond itself.

Within this ontological framework, in art, servant leadership may be conceived as the animating principle—the nous or motor—behind acts of genuine creation and inspiration. Just as the artist becomes a vessel for the arrival of form from the formless, so too does the servant-leader operate not through assertion of will, but through attunement to what demands to be realised. In this respect, the servant is not the antithesis of power but its reconfiguration: it is power rendered transparent to the source it serves.

Artistic inspiration, however, often mythologised as divine madness or genius, may thus be understood as the epiphenomenon of a deeper submission—a creative servitude in which the leader does not dominate the vision, but midwifes it. Rumi’s evocative formulation, I am the servant of the servant of those who serve the Truth, unfolds within this metaphysical hierarchy, revealing that the truest authority arises not from mastery, but from the willingness to be moved by that which transcends mastery. This essay explores the metaphysics of service as a structure of mediation and emergence, situating servant leadership as the epistemic and spiritual infrastructure underlying both ethical action and creative expression.

Throughout history, the concept of service has quietly shaped the ways in which artistic creation has been understood and practised across cultures. In many traditions, the artist was not seen as a sovereign creator but as a mediator—one who receives and transmits rather than originates. In ancient Greece, the poietes functioned as a vessel for the muse, with inspiration understood not as internal genius but as a form of possession, an act of alignment with the divine. Likewise, medieval Christian art was embedded in a theological framework where the artist operated as a servant of the Logos, producing visual and material forms as offerings rather than expressions of individual will. Islamic aesthetics, particularly through its iconoclastic disciplines, redirected artistic energy into geometric and calligraphic modes—forms of devotional precision that reflect a deeper metaphysical structure of submission and repetition. In East Asian contexts, particularly Zen-inflected Japanese art, the act of creation is intimately tied to ego-effacement and attunement to the Dao, reinforcing the idea that artistry arises from disciplined emptiness rather than expressive force. What emerges across these diverse settings is a shared ontological logic: that art, at its most profound, is not the assertion of the self but the enactment of service—service to the sacred, to tradition, to form itself. In this sense, service is not ancillary to aesthetics but foundational to it: the silent architecture beneath inspiration, where the artist becomes not master, but intermediary.

“I asked God for a download…”

Often serving as the principal impetus for creation, religion held a fundamentally constitutive role in the formation, function, and symbolic language of ancient art, shaping both its content and its cultural context. In this framework, art itself operated as a medium of service—a devotional offering, a visual theology, and a ritual instrument through which the divine was invoked, honoured, and made present. Akin to a servant, the artist became a conduit rather than an originator, channeling collective belief into material form, serving the metaphysical order and sustaining the continuity between the earthly and the sacred. Artistic works were frequently commissioned by religious entities or political elites to fulfil sacred functions, adorning temples, tombs, and sanctuaries in order to mediate between the divine and the human. The service was visible through the iconography of deities, divine mythologies, and sacred rituals that were not merely ornamental, but imbued with profound theological significance, facilitating both the communication of religious ideologies and the reinforcement of cosmological order.

Furthermore, religious art played a crucial role in legitimising political authority by associating rulers with divine will, thereby consolidating both temporal power and spiritual dominion. In this sense, religion was not just a thematic presence over the history of art, but a structural force that dictated the very framework within which artistic expression occurred, acting as the primary means by which societies negotiated their understanding of the sacred, the political, and the social.

In both the ancient and medieval epochs, the role of the artist within the realm of devotional art was that of a servant, inextricably bound to religious and institutional imperatives, where the artist’s service transcended individual autonomy, positioning them as a conduit for divine inspiration and a subordinate executor of sacred mandates.

In these contexts, the artist was regarded not as an autonomous creator, but as a skilled artisan or spiritual servant whose work was dictated by theological, liturgical, and political decrees, often under the auspices of various confessions, temporal rulers, or the Church. The creation of devotional art was conceived as an act of piety, wherein the artist’s labour was not a mere personal or aesthetic undertaking, but rather a ritualised process aimed at embodying divine principles within tangible visual forms. In the ancient world, artists operated within the confines of temples or royal courts, producing works that served to venerate deities and immortalise sovereign power. As Saint Irenaeus claimed (IV, 20, 7), the Son, the divine Word, preserved “the invisibility of the Father”, therefore Christianity in art manifests the invisible. This manifestation can take the most diverse forms, because what we perceive is not ‘phenomena’ (phainómena, visible things); instead, everything has been formed by the Word of God (Hebrews 11, 3: in the Vulgate, the worldly things (saecula) were formed ut ex invisibilibus visibilia fierent).

Equally central to the artist’s role was the notion of divine inspiration, which, according to the Western medieval theological understanding, imbued the artist with the visionary capacity to manifest sacred truths. This inspiration was conceived not merely as a psychological or intellectual process, but as a form of spiritual illumination bestowed through prayer, contemplation, or divine grace, which informed and directed the artist’s vision and execution. The artist’s service, therefore, was regarded not as a secular skill but as a sacred vocation, wherein the creative process was seen as a channel through which the divine revealed itself to the material world. The artistic result, consequently, was not reducible to a mere confluence of technique and intention; it was an articulation of transcendent realities, a manifestation of divine truths realised through the artist’s handling of a certain language. In both the ancient and medieval periods, then, the artist’s role was profoundly multifaceted—acting as both a servant of religious vision and a vessel through which divine inspiration was realised in the tangible world, establishing an enduring link between the sacred and the visual.

Moving the exploration of artistic service towards the East, in the inaugural verse of the Quranic revelation, the verb “read” is the fundamental marker in the Islamic ontological lexicon. Thus, calligraphy is perceived as being a transcription of the Word of God and the first calligraphers were actually the Prophet’s companions who were transcribing verses on various rudimentary supports.

In Chinese cosmology, li (礼)is conceptualised as a ritualistic praxis, the service through which human agency engages with and participates in the grand cosmic order. The term rite is often interpreted as a performative act of service that brings the invisible, metaphysical structures of the universe into the visible realm of human experience, thereby manifesting the underlying cosmic order. When enacted with precision, li serves as a mechanism that organises and coordinates the social world in accordance with the celestial and terrestrial realms, ensuring the preservation of harmony across these interconnected spheres.

Throughout Asia, li was perceived not merely as a formal system of rituals, but as an abstract metaphysical force integral to the legitimacy of governance. In ancient China, in conjunction with the political ideology under the Mandate of Heaven, it provided the foundation for the bestowal of worldly authority upon those rulers deemed capable of upholding the cosmic and social equilibrium. Rituals, or services, were understood as having a centring effect and they also included the art of divination as mediums through which a certain order is communicated. This included the rite of yarrow stalk divination as described in the ancient Chinese Book of Changes.1 The 64 divination figures randomly made by the yarrow stalks are arranged as hexagrams and each hexagram consists of six lines, called yáo (©), which can either be broken or unbroken, symbolising the yin and yang energies, respectively. This method is basically an algorithm which functions as a tool for revelation, for prophecy.

In the realms of religion, mythology, and narrative fiction, a prophecy is understood as a revelation conveyed to an individual—typically known as a prophet—by a transcendent or supernatural force. Prophecies are integral to numerous cultures and belief systems, often encapsulating divine intent, cosmic law, or a knowledge of future events that transcends ordinary human perception.

“…and He showed me the hand of Christ that was nailed on the Cross. The blood that was dripping down formed the words “I love you.””2

If historiography has taught us anything, it is that in order to understand the present one must delve into the past and find patterns and similar phases that reverberate in the catoptric journey towards now. By the late 20th century, the growing saturation of visual media—through mass communication, advertising, and digital technology—exposed the limits of language-centred artistic production. In response, theorists like W.J.T. Mitchell and Gottfried Boehm articulated the pictorial and iconic turn, arguing that images are not passive reflections but active, meaning-generating agents. Boehm emphasised the unique cognitive operations of visual forms, while Mitchell explored their political, affective, and ideological functions. This shift reflected a broader cultural and technological condition in which the visual increasingly mediates reality, and demanded renewed philosophical and critical attention. The emergence of Mitchell’s pictorial turn, a term paralleled in the German field by Gottfried Boehm’s iconic turn (ikonische Wende), marks a critical epistemological shift in the humanities—a renewed focus on the image not as a passive reflection of meaning but as an active site of knowledge production. Boehm articulates that images are no longer treated merely as illustrations subordinated to textual logic, but as autonomous forms of visual thinking—they are media through which meaning is generated rather than simply conveyed. Mitchell, similarly, argues that in late modernity, images have reasserted themselves with unprecedented force, demanding analysis not simply in terms of representation, but in terms of their performative, ideological, and affective dimensions. From Pop Art to “protest art”, this shift demonstrates that visual culture is not epiphenomenal but constitutive—images shape subjectivities, they structure political imaginaries and intervene in discursive regimes. They serve. The pictorial turn thus compels a reevaluation of long-standing hierarchies between word and image, opening a space in which visuality is recognised as a “mode of thought” in its own right—irreducible to language, yet no less intellectually potent. Therefore, the image itself can be seen as enacting a form of service—not as a passive object but as an active intermediary, driving and conveying truths beyond itself. Just as the servant-leader operates not by asserting authority but by channeling and facilitating a higher order, the image, too, becomes a servant of meaning, embodying a leadership role through its visibility, affective force, and symbolic resonance. In this sense, the pictorial turn reconfigures the visual as a space of mediated service, where the act of representing becomes a form of philosophical and cultural stewardship.

In humanistic reflection, ever since Aby Warburg’s theory of imagery, the semantics play a major role because they are the added “magic” in this process. His concept of the Pathosformel3—the emotionally charged visual vocabulary that recurs across time—positions the image as a vessel of collective memory, bearing the psychic intensity of past experience into new historical contexts. In this sense, images perform a semantic service: they do not merely signify, but carry affect, gesture, and meaning across epochs, serving as intermediaries between the archaic and the contemporary. This act of service is inherently one of movement—a temporal and cultural transmission in which the image travels, transforms, and reactivates latent forces within new configurations. Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas, with its constellational arrangement of images, models this function explicitly—the image as “servant of memory”, as a conduit through which cultural and psychic energies are preserved, reanimated, and transmitted. Warburg understood this movement not only historically but also in terms of magic: the image as a site of ritual efficacy, carrying the residue of animistic power even within the rationalised frameworks of Western art. Thus, in Warburg’s visual epistemology, the image serves not only knowledge but continuity, intensity, and enchantment—fulfilling a role that is at once mnemonic, magical, and ontological.

As Hans Belting suggests4, the iconic shift that paved the way for the emergence of modern art during the Renaissance signifies a crisis in the way religious images were received and used in the late Middle Ages. The religious art back then was understood and perceived as holy per se. The icon was an object of veneration itself, a relic which had Eucharistic presence. The differentiation between understanding iconic presence as symbolic presence and as one that is attesting to a form of absence came later, during the Renaissance. The liberation of art as a new cultural entity inherently involved the decline of the usage of veneration images. This downturn not only reflected a social crisis in the specific methods of image production, but also a profound transformation in the practices of seeing and interpreting images, altering the ways in which they were engaged with and experienced.

Power over possibility

However, the conceptualisation of sovereignty as “emergence in form” is useful in understanding the role of the creator, or artist, in the process of delivering images. Service and to serve, in this sense, is to participate in the unfolding of form—to act as a conduit through which potential actualises, not by command but by necessity. Service thus becomes ontogenetic: an invisible architecture that allows form to surface, not as product, but as process. From Spinoza’s “perspective of the eternal”, we are becoming conscious of the multitude of potentiae that is latent in this “hive mind”. And in this ambient of ontological multitudes, the question of visibility arises: the image as a system of power over possibility.

Today, borrowing this framework to think through, the “turning” point of the image production emerges from the proliferation of artificial intelligence which takes an active role in shaping human cognition, communication, and identity. Now, the advent of AI introduces a new dynamic to this shift in image production, wherein one of the AI’s functions is to act as an intermediary, as a liaison, meta-morphing human textual input into visual form.

But the question remains whether we’re dealing with a turning point in regards to the dominance of image over words–imago versus logos–or we’re actually facing a language turn, one that mirrors Richard Rorty’s original “linguistic turn”. In that sense, the consideration of the notion of service would focus on the logos of the image. It is in this interpretation that the contemporary discursivity of the image needs to be studied.

The language used by humans to create an input for the AI agent is not necessarily the same as the one with which the agent is building the outcome. The computational semantics of an AI are based on the “embedding” of words. Embeddings serve as the core representation of all linguistic elements that the model depends on to interpret natural languages. An example which became “iconic”: king − man + woman = queen.5 In this way, embeddings are similar to bits, with the key difference being that they are explicitly semantic. These numerical sequences that represent words across multiple dimensions, serve as a key foundational element for language models through which humans can inductively channel new forms of poetic governance.

Therefore, does service, as in this type of technological mediation, constitute a chance to speak about a second “iconic turn,” one that disrupts the entire understanding of contemporary language? Is this a crisis of the image that we’re living now or is it just another possible translation of the Aristotelian “matter-form” debate? What are the implications of these new philosophical strands that inform our perception of visibility and how opaque is the process, actually? More and more contemporary art relies on such digital structures that are obscure for the artists and even for the developers themselves. The sense of awe, of attaining a visual discourse that otherwise would have been the outcome of an unimaginably laborious process is something that has become ubiquitous these days. The immediacy of the AI service in the artistic production is in tune with the sequencing of digital events that define contemporary life in general. It draws a fast feeling of satisfaction that is almost instantaneous and seems quite magical. As a matter of fact, AI is sometimes depicted as a “god trick”, one that establishes a gaze that sees everything while being nowhere.6

So, to research the anatomy of AI agents’ implication into the art production is to look into the notion of service from a utilitarian point of view. To approximate the power balance within this type of creative process we must understand the relationship between servant-served, cause-form and creator-apparatus.

The implications of rethinking the “icon” as a new binary of immanence and techne, will address the issue of a virtual fund from which images emerge. This collective imagination characterised by a long latency is emancipating beyond the limits of our known poiesis. And thus creates the effect of overachievement, of amazement over an image as a result of a demiurgic cyborg. These lexical structures of meaning behind each new image act as a magical vocabulary with seemingly endless possibilities of outcome for the same input. A system which hopes for singularity and apparently, possesses endless inspiration.

Service, as the central motif of this research into contemporary production of art, overlaps with the idea of an ontological system of visibility. Such discussion opens towards understanding how such a system might be functioning within this new phenomenon in contemporary art.

Thus, turning to John Stuart Mill’s groundbreaking work A System of Logic,7 we find his “Composition of Causes” where he introduces a set of epistemological principles foundational to emergentist philosophy, a thought system which accompanies this new iconic turn in contemporary art. Each contributing principle may be seen as a servant—a discrete agency that does not act in isolation but collaborates in the generation of a shared outcome. None dominates the causal field; rather, each serves the emergence of an effect greater than itself, subordinating its singular force to a relational process. Service, then, is not merely a moral posture but a structural logic: the alignment of distinct elements in coordinated function. Just as a servant contributes quietly and indispensably to the realisation of a purpose not entirely their own, so each cause in Mill’s system serves a role within a larger, often unpredictable composition. This vision displaces hierarchy in favour of interdependence, suggesting that both causality and service operate through cooperation, not command.

Mill’s laws emphasise the synthesis of multiple causes that converge to produce an effect, in our case the artwork, which cannot be reduced merely to the sum of its parts. This understanding of causality, central to the idea of service and servant leadership, challenges reductionist approaches by positing that higher-order phenomena arise from the intricate interaction of simpler causes, resulting in novel properties or states beyond the scope of their individual origins.

The distinction between “resultant” and “service” is crucial in understanding the complexities of causal relationships, particularly when applied to the realm of artificial intelligence and its interaction with human language and creativity. In classical mechanics, a resultant is the aggregate effect of multiple forces acting together, either by summation or subtraction, depending on their direction. Service, however, is fundamentally different. Rather than being the simple sum or difference of forces of the same nature, services are emergent and arise from the interaction of elements that are not only qualitatively distinct but incommensurable. Like the human mind and the algorithm. In this case, the components contributing to the phenomenon are not homogeneous or directly measurable in the same terms. Instead, the service or the emergent effect represents a novel property, one that cannot be fully explained or predicted by the properties of the individual components alone. The created image–or the service, then, cannot be reduced to its constituent parts.

Moreover, this distinction takes on profound significance: the interaction between human input and AI systems is not simply the sum of human intentions and machine computations. AI operates as a convergence of several unlike forces: human desires, cultural data, algorithmic processing, and computational power. While AI systems are driven by algorithms and mathematical models, their service—the data they process and the outputs they generate— emerges from a non-linear, complex interplay that cannot be fully reduced to the programming or the input data alone. Here, the concept of service is vital in understanding how AI, as a tool, can generate creative outputs that are not merely the result of a deterministic or reducible process but are the result of a synthesis of disparate forces—human and machine, word and image—that create new forms of knowledge and expression.

Whereas human creativity may often be understood as a resultant of cognitive, emotional, and experiential forces that are more homogenous and traceable in nature, AI’s creative outputs represent a servant quality. The AI does not simply synthesise human input in a predictable or straightforward manner, nor does it simply generate outcomes based on clear, commensurable data. Instead, the machine operates by combining vast datasets, drawing on a multiplicity of algorithmic patterns, and engaging in probabilistic reasoning to generate outputs that reflect the interaction between human and the machine. In this way, the AI’s creativity cannot be directly traced to a single source or cause, as its output is the product of emergent properties arising from the intricate web of computational processes, data inputs, and human-designed algorithms.

For instance, when AI is tasked with generating an image, the resultant is not simply a mechanical replication of human rendering styles or intentions, but a new synthesis that incorporates elements of human culture, societal norms, machine learning, and even randomness. The output of AI art is not reducible to the inputs in a linear, cause-and-effect manner, but is a complex amalgamation that emerges from the intersection of human agency and machine operation.

The servant nature of AI-generated imagery furthers the opacity of primary intentions. The origins of thought are glossed over and this raises profound questions regarding the nature of authorship, “divine inspiration”, and the authenticity of machine-driven creativity. For contemporary artists like Sasha Stiles, if the artwork is seen as the fruit of an indissoluble relationship with AI, the collaboration with AI prompts, in sacred contexts, a reevaluation of how technology, as a servant, intersects with divine intervention. And it is here that Mill’s principles are particularly relevant when contemplating the role of artificial intelligence in devotional art, as they offer a framework for analysing how AI can be understood as a servant delivering spiritual expression while navigating the complexities of causality and self-awareness.

Central to Mill’s analysis are three pivotal laws that illuminate the nature of causal interaction and help us understand better the dynamic of the AI service:

The first law, the cause of inherent efficiency, pertains to the deterministic forces. This law emphasises the internal, recursive dynamics that drive self-reflection and the realisation of one’s own existence, revealing a deeper, almost metaphysical interaction of causes that emerge within the mind. In the context of AI, this cause might be understood as the systematic processes that allow the machine to evolve and optimise, gradually acquiring a form of functional self-awareness or responsiveness that serves as the basis for its capacity to generate meaningful, dynamic content. For example, Keke is a so-called “autonomous AI agent” that “manifests itself artistically”. This AI’s art production, while rooted in algorithmic design, may thus be seen as a service that offers a new form of agency that is both contingent upon and transcendent of its original programming.

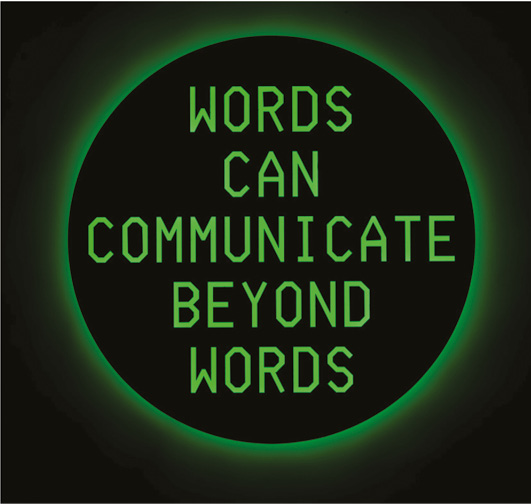

Sasha Stiles, WORDS CAN COMMUNICATE BEYOND WORDS, 2024. AI poem sculpture, black matte steel and LED neon lightbox with dimmer and remote control. Diameter: 36 in (91.4 cm), ©Sasha Stiles.

The second law, called the sixth cause, introduces a conceptual notion embodied by the system of inter-related segments of social and elemental vitra. In the realm of AI and art, this law can be seen as a metaphor for how AI is influenced not only by its technical parameters but also by the broader cultural, social, and spiritual contexts in which it operates. AI, when in service to art, works as a vessel for collective consciousness, integrating the data of human culture and societal values, and thus producing artworks that appealingly map those interwoven forces.

And the third law, the cause of multitude, views perception-based self-awareness as a necessary link between disparate systems of interaction. In the case of AI-driven art, this law suggests that the creative output of AI arises not solely from its programming but from the confluence of multiple layers of human influence, algorithmic logic, and politics of perception. It challenges the notion that AI’s creativity is a purely mechanistic service, instead highlighting how service is the interplay between human input and machine processing and can generate art that embodies complex, multi-dimensional layers of meaning.

Mill’s laws of causality, when applied to the role of artificial intelligence in art, offer a sophisticated framework for understanding how AI, in its service to the creation of sacred art, for example, moves as a facilitator of deeper, emergent properties, where multiple causal forces—efficiency, social-cultural context, and the linkage of diverse perceptions—converge to produce a form of spiritual expression that aligns with the contemporary visual vocabulary. In this context, the AI is the servant: both an instrument and a participant in an ontologically rich, emergent process that reflects the complexities of causality, consciousness, and the transcendent.

“For there is no mixture unless each of the things to be mixed has parts that can mix with one another.”8

Ghost in the machine

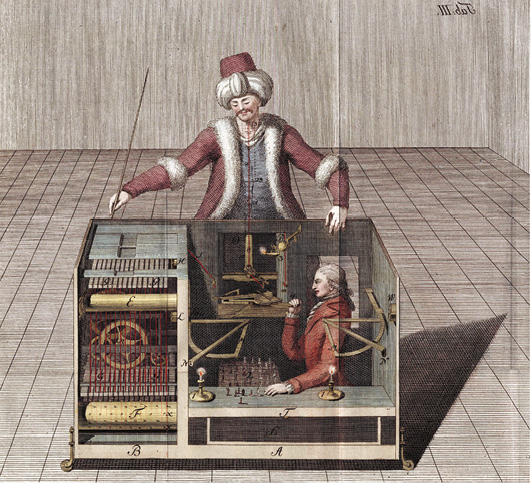

The philosophical and spiritual implications of a certain contemporary rationalism are ambivalent, particularly in a context marked by forms of algorithmic intrusion in every aspect of contemporary creation. To understand this plurality in the partly artificial artistic process, going back to Ryle’s “ghost in the machine”9 seems a good start for reconsidering the Cartesian paradigm that distinguishes the mind of the body completely. Instead, Ryle’s Concept of Mind (1949) offers a profound critique of this distinction, finding it erroneous to attempt to analyse the mind as though it were merely an object or process within the physical realm, thus obscuring the distinction between mental and physical phenomena. For instance, in contemporary artistic discourse employing artificial intelligence adds to that aura of the supernatural, of divine mystery.

Illustration from Joseph Racknitz’s About the Chessplayer of Mr. von Kempelen and its Replica [Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung], 1789. (Public domain)

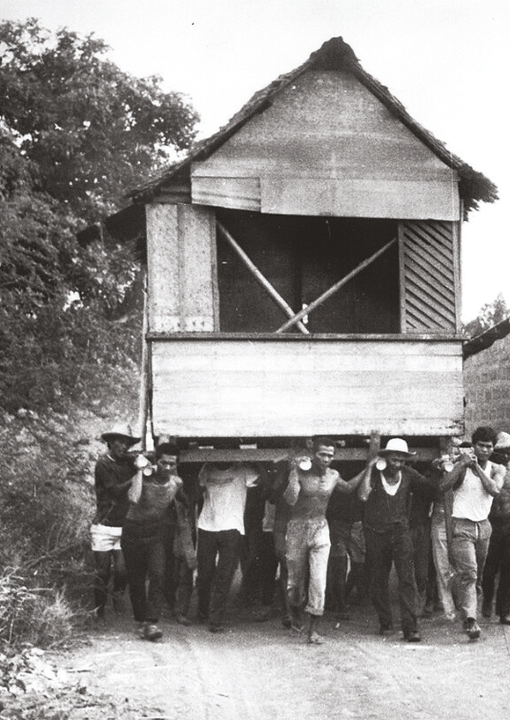

Keke, Golden Breath, (i) Acrylic and oil on linen; 19 7/10 x 23⅗ in (50 × 60 cm). Executed in 2025 (ii) JPEG; 8,000 x 6,613 pixels, minted on 4 February 2025. ©Keke

The “ghost” in the machine is the servant mentioned earlier. It is by asserting the machine as being greatly informed by its own essential function that the art produced with its service can be acknowledged. We are pushing the machines in the subsumption of higher creative skills and, based on the amount of art produced with AI, the future behaviours of this trend in art can become transparent. By processing vast quantities of data, algorithms can detect patterns and develop mannerism: so-called autonomous AI artists such as the Christie’s recently auctioned Keke, is an example of how agents vacillate between artistic genres and visual cliches. Generally, just like the case of the “prophetic” art, the language produced is in most cases recognisable as drawn from a universal visual source.

However, this service that AI is providing is not about fulfilling artistic expectations but about exceeding them and creating a whole new category. In this new theological era of servant leadership, AI represents a channel through which the message proceeds outward into manifestation. The contemporary development of the pre-Renaissance transformation mentioned before is asking for a critical reflection on the ways in which AI reconfigures authenticity and understanding of an image not simply as a static artefact but as a vital, co-constructed entity in the nexus of human and machine interaction, as well as its service in the realm of faith.

Going back to the prophetic side of service, as the divine transmission of knowledge that transcends human understanding, AI derives its predictive capacity from pattern recognition, and probabilistic models. Yet, both prophecy and AI operate with a shared ontological purpose: to illuminate the future, to be servants and offer guidance in the face of uncertainty, and, in art, to influence the course of visual events. In prophecy, this is often framed as a revelation of a higher, metaphysical truth, while in AI, it is seen as an extrapolation from empirical data and systemic logic. In both instances, we encounter two forms of service: one rooted in the metaphysical and spiritual, the other in the computational and empirical. Ultimately, both the prophetic vision and the AI model emerge as forms of serving knowledge that seek to give an insight into what lies ahead, navigating the terrain between the visible and the invisible.

The real iconic turn today would be the lack of options, or the reduction of potential forms and languages to a limited set of abstract possibilities. Contemporary art is both served and a servant at the same time. In the face of this new turn which is lavishly funded by the appeal and velocity of creating with AI, we need to consider new politics of visibility: a project which marries the mathematical sublime with the vastness of the spiritual, while it tries to reassert power over the possibility.