Abstract

Centre for Contemporary Culture KRAK and its practice is understood through the prism of specific political, social and cultural conditions in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the past three decades. The main features of this are the conflict-related and post-traumatic experience, corruption and failed transition, as well as depopulation. Since its opening in 2020, KRAK created an independent and critically-oriented space within which innovative ideas have been generated and articulated. As such, KRAK Centre is a direct response to lasting crisis. It is a direct reference to the dominant and aggravating circumstances facing Bosnian and Herzegovinian society today, and therefore, it is an experiment because of the belief that culture, science and arts need to be the driving force for social changes. With its strategies of conviviality, care and emancipation, KRAK is perceived as social practice – a service, far from governing and instrumentalised state-funded agencies.

This paper gives insight into curatorial practice in the socially abandoned and neglected urban environment of the city of Bihać where KRAK is located. It also deals with issues related to work in the fields of contemporary culture and art, and being engaged in the European periphery today. Since Bihać with\its specific geography in this context can be perceived as a starting point for understanding the complex political, social and cultural layers within which KRAK operates, this paper contemplates the distance between the artistic image and real life in the context of the European periphery and its marginalised environment. Additionally, it initiates a discussion on present relevant issues in a traumatised, post-war and post-genocide society, searching for possible answers to the questions: how to articulate an artistic discourse on the European periphery and how to motivate urban reinvention in a post-socialist and post-industrial spatial context.

About the context

Bosnia’s path into independence, in the last decade of the 20th century, was marked by turns and discontinuity. Once part of the socialist Yugoslavia with a one-party system and centralised economy, Bosnia and Herzegovina is now a young democracy in development. Stretched between the legacy of self-governing Yugoslav socialism and privately-oriented neoliberal capitalism, Bosnia’s way into liberation was marked by ethnic cleansing and genocide from 1992 to 1995. The collapse of Yugoslavia as well as the conflict that followed, initiated a long-lasting turmoil that is still present. Even thirty years after, Bosnian society is still involved in conflicted discourse with immense impact on society, culture and economy.

A crucial perspective for understanding the post-war landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina can be gained by examining its cultural and artistic institutions. The state of culture in the country cannot be discussed without acknowledging the cultural crisis, which stems from the poorly constructed Dayton Peace Agreement of 1995.1 By signing the Dayton Peace Agreement in 1995, the legal status of these institutions remained deliberately unresolved and seemingly postponed for some better times. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s ethnocracy, formalised by the new constitution, has “lowered” cultural issues from the state to the regional and county levels, bringing into question the collective cultural identity of the entire country, limiting and minimising it.

Such an attitude has weakened the awareness of the importance of culture in general; key institutions have been marginalised to the extreme and some even shut down. Within a complex legal framework, counties and municipalities missed the opportunity to take over what the state failed to do—the regeneration of devastated cultural spaces. Culture eventually died out and was recognised as useless and passive, as an object of constant tension, problems and unfinished processes.

In addition, the poor territorial organisation of Dayton-mandated Bosnia and Herzegovina—which did not follow the geographical characteristics but the results of the brutal seizure of territories and mass expulsions—made its cities disconnected from one another. Territorial defragmentation and ethno-national divisions, further isolated and aggravated the situation of the country as a whole. The Dayton model has long shown its unsustainability, with the parliamentary political nomenclature unable to redesign the existing constitution for fear of possible losses of war booty.

Cities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, although in the process of development and construction, were places of sophisticated industry with a developed urban middle class before the country’s independence in the 1990s. After the war and the signing of the Dayton Agreement, the position and importance of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s cities was redefined due to the new reorganisation—they were industrially devastated and demographically weakened. In some of them, new institutions of general importance have been established, such as universities, galleries or cultural centres. Although for a moment it seemed that these cities were facing new social challenges, many opportunities have not been used enough since the end of the war onwards.

Continuously poor policies at all levels of the state, disintegration in the education system as well as radical provincialisation aided by changing demographic conditions have turned Bosnian cities into isolated and closed provinces on the margins. Pseudo-democracy, parliamentary travesty, corruption and clientelism, together with neoliberal tendencies of a global character, have served as a framework for unprofessional and unethical reflection on the heritage and cultural identity.

Within such an environment, cultural institutions have been contaminated with apathy, lack of any momentum, and lack of ideas. Many of them have found themselves in a vicious circle that perpetuates the crisis. The absence of public discourse on culture, the lack of cultural strategy at the state, entity, cantonal or municipal levels and the lack of creative ideas have created an environment in which below-average cultural practices are established, that include courting the citizens and the public with insufficiently critically attuned and entertaining contents.

Disinterest and general ignorance have bypassed the awareness that culture is an agent of social change, that it has the power to identify and re-identify society with new models, as well as the power to reshape the consciousness of an individual and a group towards something new.

Perhaps the most important non-institutional art project in this direction in the country, is the Ars Aevi Museum of Contemporary Art in Sarajevo. Even while Sarajevo was under heavy attack during the siege in the 1990s, the idea of the Museum was born. The initial idea of its creation was based on “the conviction that the artists of this age feel and understand the injustice done to our city.”2 Thus, the project, which was administered from the beginning as a civic organisation and not as a public institution, encoded the idea of proactive action based on the need for civil resistance to war destruction and the natural desire to open the besieged city and connect it with the wider world.

The expectations of the significance and scope of activities of an organisation were surpassed with Ars Aevi, because in its breadth and depth it managed to produce incredible results. Under the leadership of Enver Hadžiomerspahić, former director of the opening programme at the 1984 Olympics, and later director of cultural programmes at the Skenderija Olympic Centres, Aevi remained involved in the fight against the devaluation of general social and cultural values in its community. A careful curatorial selection of several collections that would form the basis of the future museum, it was accompanied by a painstaking engagement in the administration of the entire idea, only to become a Public Institution of the City of Sarajevo in 2017. From the formation of the first tangible collection until today, Ars Aevi still does not have formal headquarters and has moved several times, although its main architectural conceptual design was made by the well-known architect Renzo Piano.

Ars Aevi is a cultural and artistic idea that, with its constituent elements, speaks about the phenomenon of the crisis in the field of culture and art in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is the paradigm of a new era that began with the unfortunate war of the 1990s, and which no longer has the capacity to base a projection of itself on events and happenings before that. Ars Aevi is tangible with its problems and challenges, in contrast to the cultural institutions formed after World War II, which is a distant history that is difficult to understand and turn into paradigms with which today’s society could identify. Although Ars Aevi represents the logical development of an urban environment, in its essence it is a symbol of an interruption, break and discontinuity caused by war.

Although there are funds at all levels that cover the needs of culture and art, it can certainly be said that their implementation is marked by nepotism, corruption, bad criteria and constant reduction, that is, by abolishing the available funds. The existent state-funded Foundations do not suggest seriousness and commitment, while the process of evaluating the received applications and allocating funds takes place in a non-transparent and clientelist way. Viewing nationality as a key element, incompetence, bureaucracy and deadly formalism are just some of the characteristics of how these funds function.

Non-institutional involvement is a counterpoint to the aforesaid and a reflection of the responsibility of citizens and individuals to resist the general decline and systemic devaluation. It is often motivated by the crisis of society, ranging from systemic state negligence, official ethnocratic organisation, but also commodification due to the uncontrolled restoration of capitalist ownership relations in post-socialist Bosnia and Herzegovina. On the other hand, the above-mentioned problems on the scene of Bosnian culture, which are most evident through issues of institutional action in the range between the legislative and executive power, are a suitable environment for social practice and civic engagement. This type of action is marked by a discerning judgment of the validity of official practices of parliamentary political discourse, and is operational in clear spheres of assessment and action. Of course, this fits into the global trend of “increased tendencies to subject politics and art to the moral judgment of the validity of principles and the consequences of its practices.”3 An ethically informed approach on the cultural stage does not make all parties happy but on the contrary, it provokes, confronts and polarises.

A potential contextual comparison for Bosnian cities can be drawn with Detroit, a U.S. city shaped by postindustrial challenges marked by racial and class divisions, impoverishment, and depopulation. Once a symbol of American industrial progress, Detroit also became a testing ground for racial capitalism and systematic segregation, which fueled conflicts and urban displacement. Straddling the extremes of poverty and prosperity, Detroit has struggled over the past few decades to regain its former status as a quintessential American capitalist hub. Factors such as disinvestment and industrial decentralisation since the 1960s have contributed to this decline. Once a global industrial powerhouse in the first half of the 20th century, Detroit now stands as a striking example of radical decline, offering a peculiar and diverse set of opportunities. The reality that “you can do all sorts of things that you can’t do elsewhere” is both inspiring and unsettling, positioning Detroit as a major post-American city.4

KRAK Centre and curating the periphery

Centre for Contemporary Culture KRAK, in northwestern Bosnian city Bihać, was established in 2020 as a result of endeavours in the field of critical theory, art/design practice and civic engagement generated in the last several years around the Department of Textile design at the University of Bihać and City Gallery. It is an independent and autonomous space that emerged as a result of continued scientific observations and their practical implementations from 2011 onwards. Its conceptual context is framed by post-socialist and post-industrial characteristics—unsuccessful and painful transformation from Yugoslav socialism into post-Yugoslav neoliberal capitalism. The main marks of that period are conflicted relations, depopulation, poverty and trauma.

Public talk Curating the Periphery. Molly Haslund, Zdenka Badovinac and Šejla Kamerić in conversation with Irfan Hošić. KRAK, October 2023. Photo by Mehmed Mahmutović.

The focus of KRAK is on contemporary culture including visual arts, design and social theory as a frame for proactive practice. It is imagined as a participative project with different protagonists who use the tools of social engagement and urban transformation to foster process of learning, informal education and cultural exchange. KRAK launched its first program in 2021 where questions of migrations, identity, public space and visual culture, were articulated. Using curatorial practice with the intention of intervening in socially relevant processes, KRAK deals with the challenges of working in the field of contemporary culture and art in a context characterised by post-war, post-socialist and post-industrial trends.

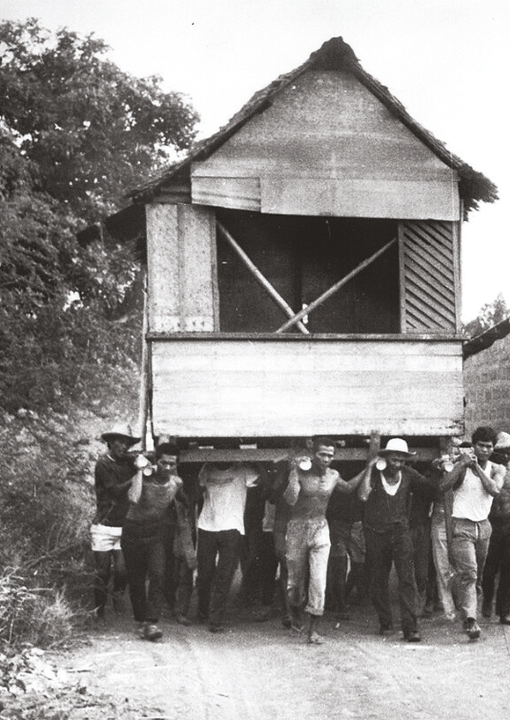

After years of neglect and after several prompt discursive actions organised in the Kombiteks Workers’ Club in recent years, the Council of the City of Bihać as owner, handed this space to the Revizor Foundation to open in its premises the KRAK Centre.5 The name KRAK is an acronym for “Kombiteks Workers’ Club” (Klub radnika Kombiteksa) and is directed to sustain the importance of cultivating local industrial heritage and workers’ culture of Yugoslav self-management socialism.

After several years of operation, KRAK serves as a bridge between the Yugoslav industrial past and its self-management socialism, where the “commons” played an important and systematic role. Thus, KRAK can be understood within the frame of “art of the commons”—the practice that lies as “an indeterminate zone between public and private” space.6 The cultural critic Carducci writes:

The art of the commons trespasses the boundaries of conventional property relations of modern capitalism, existing in an indeterminate zone between public and private as customarily understood (…) Collective freeing of land and labour from capitalist economic and social relations.7

As such, proactive artists and various practitioners are imagining new politics of space, initiating important questions as to whom the city or the neighbourhood actually belongs. Artistic interventions of that kind serve as a strong defense against centres of power and control that are traditionally in alliance with investors and very often dehumanised architects and designers. Community art projects of this kind are “challenging political messages meant to provoke discussion on issues of poverty, racism and social disintegration that informed the quality of life for the community.”8

Although Bihać has several cultural premises that are all organised as public institutions, the launch of an alternative and independent space in the field of culture represents a necessity of the city of Bihać and its urban life. KRAK is oriented and focussed on contemporary cultural practices such as visual arts, architecture, design, performance, dance, music, science, alternative education and ecology, with interaction with the most diverse types of citizens and groups of different profiles.

The idea and motive for launching such a centre stems for the specific political, social and cultural conditions in the country in the past two or three decades. The main features of this are the city’s neglected industrial past, the conflict-related and post-traumatic experience, and depopulation. Of course, it is a perfect seedbed for the conceptualisation of dynamic practices of total engagement through the establishment of an independent and critically oriented incubator within which creative ideas would be generated, where new generations of socially responsible individuals would get together. The KRAK Centre is a direct response to the lasting crisis. It is a direct reference to the dominant and aggravating circumstances facing Bosnian and Herzegovinian society today and, therefore, it can be understood as an experiment because there is a belief that culture, science and arts can and need to be the driving force for social changes.

In the long run, KRAK wants to position itself as the platform for alternative learning, collaboration and coexistence with a focus on contemporary artistic strategies and inventive cultural protocols. Participation of a wide spectrum of professionals and amateurs—artists, architects, designers, educators, lawyers, activists, gardeners, environmentalist, bee-keepers, as well as legal entities motivated to be profiled and engaged in socially responsible practices—is the key aspect and the fundamental premise of potential activity aimed at shaping a new social reality. KRAK wants to be tested as an incubator of a new social life.

Considering Detroit as an ideological counterpart, with its practical initiatives and diverse social practices “that stands as a collector of social value for the creation of a sense of community as a result of multidisciplinary collaboration,” one notable example is the Akoaki design studio.9

Akoaki is an architecture and design studio founded by Anya Sirota and Jean Louis Farges in 2008, with a mission to engage with the social, spatial, and cultural realities of Detroit. Their participatory and inclusive design approach has earned Akoaki international recognition. As the city became increasingly disconnected and fragmented, with vast areas of vacant land and emptiness, Akoaki emerged as an innovative initiative “bridging the commonly perceived divide between social and aesthetic practice”, whose “work explores urban interventions, perceptual scenographies, and pop actions as response to complex and contested urban scenarios.”10 Rooted in Detroit, Akoaki’s site-specific designs align with the idea that “Detroit represents an exceptional opportunity to promote a new culture of work that puts the relationship among people at the centre.”11 However, the founders recognise that “design alone, unfortunately, does not have the force to answer these pressing needs.”12 Sirota addresses how design, on a larger scale, can provide a platform for participation and interaction, highlighting that inclusive design has a profound psychological and emotional impact on people. “What design can do is to create an environment for every single individual, a protected space where they can give voice to their own opinions, experiences, aspirations and problems, allowing us to modify the common perception of the city and reveal a multitude of stories that would otherwise remain hidden.”13

KRAK’s forerunners

A crucial event that served as a booster in reinventing and conceptualising the former Workers’ Club into KRAK Centre, was the exhibition Artefacts of a Future Past in 2017. It was realised in the framework of the two-day symposium Industrial Heritage in Bihać between Reality and Vision that aimed at tackling a series of “complex issues of urban planning, architectural, aesthetic, ecological and social context of abandoned industrial facilities” with a potential projection of the picture of “creation or recreation of spatial contents that open the possibility for discussion about social engagement, social practices and cultural activism in our community.”14 This symposium was organised as a part of the Design and Crisis course conducted at the Textile Department of the University in Bihać within the summer semester 2017.15

The exhibition was documented within the same publication published by Foundation Revizor in May 2020. The publication was produced three years after the realisation of the eponymous exhibition and at the moment when the space where the exhibition was held, the Kombiteks Workers’ Club, faced a completely different destiny. The catalogue and documentation imbued the publication with the character of a manifesto for the future KRAK Centre. It is the best way for interpreting the works that were exhibited there in March 2017. What was on the horizon of expectation in the process of conceptualising the organisation and set-up of the exhibition has become today, two years later, an integral part of immediate experience.

With the transformation of the above-mentioned space, preconditions for a new beginning based on heritage were met, and the publication served, in addition to being a catalogue and documentation, to reposition—from the newly created situation—the field of interpretation for the reading of individual works, the exhibition as the whole as well as the social context in which it was emerged. From this perspective, the exhibition can be understood as an articulation of guidelines in the long-term consideration of the programmatic development of the space after its revitalisation, and as its cultural upgrade, art, social responsibility and creation of the community.

The exhibition Artefacts of a Future Past is a collection of objects with a documentary, artistic and engaged character that initiated discussion of a layered interpretative spectrum, related to the complex process of an unsuccessful transition from the self-management socialism into a market-oriented liberal and multi-party system. The exhibition comprises a wide range of artefacts—from artworks to conceptual designs and finished designs to industrial artefacts dating back to the second half of the 20th century. Brought together in one place in the form of an exhibition, and re-contextualised through the prism of the two-day symposium Industrial Heritage in Bihać between Reality and Vision, these artefacts represent an attempt to map the phenomena of the industrial and the post-industrial era, juxtaposing them in a new critical perspective with local and regional visual art and visual culture, against today’s social context.

The exhibition Artefacts of a Future Past is an attempt to reconstruct the consciousness and memory that encompass the period of late socialism, on one hand, and the time of the multi-party system of capitalist Bosnia and Herzegovina since the 1990s until the present time, on the other. The exhibition is also an attempt to initiate a new understanding and reading of the industrial heritage of Bihać, which is expected to yield, in the long run and from a critically focussed perspective, new guidelines and new results in this field. A transformation of what was once the Kombiteks Workers’ Club with the exhibition Artefacts of a Future Past, as well as the recent establishment of the KRAK Centre for Contemporary Culture, guarantees the success of previously undertaken activities and of the long series of discursive contents that have marked the industrial heritage as a treasury of great material and intellectual potential. Culture, art and recent curatorial practices play an important role in mediation and education, while their discursive character and activistic tone are of a great relevance for a wide variety of socially engaged processes.16

The position of KRAK in the country’s post-war landscape can be understood through the dynamics of non-institutions, their strategies, and programme activities in a dysfunctional country. The term “non-institutions” refers to civic initiatives whose actions and methodologies have significantly impacted the artistic landscape of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Notable examples include the Obala Art Centre, Gallery 10m2, Brodac Gallery, Sklop organisation, Kuma International Centre for Visual Arts from Post-Conflict Societies, and Charlama Depo Gallery.17 Each of these initiatives embodies the idea of proactive action driven by a need for civil resistance and a natural desire to connect peripheral communities with the broader world.

Conclusion

The question of KRAK Centre for Contemporary Culture, its strategies, and programme in a dysfunctional country warrants a broader discussion aimed at understanding the complexity of its political, social, and cultural layers. As a compensation for unsuccessful and failed strategies of governmental institutions, KRAK’s presence in its non-profit actions, is a selfless practice of engagement and devotion. Within this context, the emergence of independent and individual initiatives can be seen as a response, with the goal of generating artistic discourse, mediating its content, and educating the public. The impact of KRAK Centre, along with similar initiatives, is significant and substantial, as each has, in its own way, contributed to the development of the local art scene, stimulated key artistic phenomena, and fostered dialogue within contemporary art practices and independent curatorial work. These initiatives also provided platforms for the exchange of ideas and acted as meeting points for international artists.

In view of the failures and its long-lasting consequences caused by the poorly designed Dayton Peace Agreement, there emerges a framework for independent artistic platforms and cultural organisations. These initiatives are motivated by the need to address key questions: How can reinvention be initiated in a post-socialist and post-industrial urban context? How can critical discourse be nurtured and articulated within the societal framework shaped by post-war and post-genocide realities? And, how can work be carried out on the European periphery and within national margins?

The Bosnian case is more paradigmatic and significant in view of rampant conflicts in Ukraine, Palestine and elsewhere. It can serve as a lesson of preservation of peace in instable regions, as it can well show the importance of culture in a post-war society—its possibilities and strategies. In this perspective, KRAK as a community hub can be perceived as a tool of emancipation and platform where new values are formed.

Exhibition Suit of Fire. Artists: Kemil Bekteši, Milena Jandrić and Vildana Hermann.

Curated by Isidora Branković. KRAK, October 2024. Photo by Mehmed Mahmutović.

Concert of Taxi Consilium. November 2024. Photo by Mehmed Mahmutović