What should sociologists and anthropologists do with the contemporary visual artists who tend to transcend manifold boundaries in their art practices? Societal construction of boundaries and markers of identity has been central in the research and academic writings. Such disciplinary boundaries are commonplace in various branches of the modern social sciences. Transcendence of the markers of boundaries have been equally significant. Interpretations of rituals, performances, and sociocultural processes in society led anthropologists to understand the social urges for structure and anti-structure.1 The creative social paradox, that is, constituting boundaries and then aspiring to transcend them, remained a thematic preoccupation for social scientists of the modern societies. When the same issues unfold in the world of artists, in their art practices, why should that not be a focus of discussion in sociology and anthropology?

The essay is broadly structured in three sections: the sociological imperatives; Navjot Altaf’s subjectivities; and a conceptual axis of service-in-collaboration. The overlapping of the three sections that occur with ample reiterations across the essay is almost a heuristic device to lay emphasis on the central concerns. One perpetual concern is to curate a transcendence of the disciplinary hesitations in sociology and social anthropology to engage with the art practices. In so doing the essay centres on an eclectically chosen part from the oeuvre of an established contemporary visual artist from India, namely Navjot Altaf. This is towards serving the need of comprehending the nuances of collaboration and service thereof, another perpetual concern in this essay. In engaging with the collaborative artworks in the instance of the art practice of Navjot Altaf, this essay shall seek to do what one rare sociologist named Radhakamal Mukerjee advocated at the advent of sociology in post-independent India. He underlined the intertwined nature of art and social structure, paving the way to understand the social functions of art. This reminder is significant after over half a century, when sociologists and anthropologists tend to be either unsure about the world of art and artists or, reduce them to mere ornamental objects of analyses. There is a larger corpus of relationship between art, art practices, artists’ subjectivity, and society. This essay unravels such a conjoined nature of art and society, drawing in Navjot Altaf’s oeuvre as a specific instance.

Premise

A reknowned and significant artist in postcolonial Indian art history, Navjot Altaf has been practicing and producing for nearly five decades.

Her works comprise paintings, sculptures, installations, videos and various site-specific creations. There is a commendable methodological broadness in her art practice that has taken her to various dialogic collaboration with artists of indigenous origin from Chhattisgarh in Central India, intellectuals and filmmakers, academics and activists. Through these collaborations, her work speaks expansively and sensitively about the sociopolitical conditions of the world we find ourselves in, causing us to reflect on the internal and external conflicts. She is interested in understanding the significance of transdisciplinary work, whose nature is not merely to cross disciplinary boundaries but to transcend social boundaries too, particularly through collaboration. Collaboration is not merely a technical word, or a mutual interest-based coming together of the artists, activists, and artisan communities for a short-term goal. Instead, in the collaborative works of Navjot Altaf there is ample evidence of what the French sociologist Emile Durkheim discussed as organic solidarity.

Durkheim was keen to understand the emergence of social interdependence among variously skilled workforce in a modern industrial society. Unlike seeing each individual expert in isolation there was an imperative to comprehend the relationship of interdependence among the experts. He coined the phrase organic solidarity for interdependence in modern society, as opposed to mechanical solidarity that prevailed in the primitive society. Unlike mechanical solidarity, those in organic solidarity ought to be more aware of the different skills and the fact that one social group cannot live without conscious interdependence with the other. The bridge between self and other, familiar and not-so-familiar was crucial for the sustenance of the modern industrial society. A notion of service without rhetoric, a relational configuration of serving one another, is embedded in Durkheim’s discussion on the division of labour in modern society. In spite of the criticism of the positivist determination of Durkheim’s sociological approaches to social relations, particularly of organic solidarity,2 the formulation tends to lend a more nuanced understanding of service in the acts of collaboration. The social embeddedness of service-in-collaboration underlines not only the organic nature but also a social longevity. In such a service-in- collaboration the personal and political, intellectual and emotional seamlessly intermingle. There is no need of an official, formal, bureaucratic and technocratic determination in such a service. Instead, as this essay dealing with the sociological nuances in the collaborative practices of Navjot Altaf shall show, there is a sense of organicism, in which personal and political, artistic and emotional, objective and subjective merge.

On this note it ought to be stated that Durkheim does not elaborate on the co-existence of personal and political in the conceptual formulation of organic solidarity. Much later the American sociologist C. Wright Mills cantered the relationship between personal and public, biography and history, at the core of sociological imagination. This was meant to educate and sensitise sociological methodological approaches and ways of seeing. Rather than venting any slogan Mills was keen to underline the presence of personal issues in a public enactment such as politics. Everything that may appear ordinary and redundant to the orthodox sociology indeed plays an integral role in the performance of politics. In Navjot Altaf’s artworks and practices we comprehend the relations of the personal and the political. Therefore, her art is evidently political. The idea of political art necessitates a return to Rancière, a key proponent of alternative Marxism. Rancière departed from structural Marxism after 1968, a significant break from the presiding structuralist Marxist thinkers of the time such as Louis Althusser and Étienne Balibar.

Such a critical break, as highlighted in this essay, is visible in the art practice and works of Navjot Altaf. Here, Rancière’s preoccupation with the politics of aesthetics in the decade of the 1990s is worth a quick mention. The sensible, that is, the sense-perceptions, constitute social order. Rancière critically deemed the social order akin to police order. This order determines the nature of art politics of an artist’s participation in the art and aesthetics. The politics lies in the distribution of the sensible, inclusion and exclusion. The art politics determines the visible and invisible, the sayable and unsayable, the audible and inaudible. Rancière was however optimistic about the politics of aesthetics that upsets the social order. There is always a possibility of another regime of art which will challenge the social order. Without defining them in linear terms, he proposes three such regimes: ethical regime, representation regime and aesthetic regime. Each regime tends to provide a sensorial order, a way of seeing and doing, and an overall gradation of the sensible. Each regime also tends to have its values; for example, ethical regime will emphasise the idea of ‘true’ art in an essentialist sense; whereas representation regime is least inclined to the vague ethical idealism, and gives birth to a hierarchy of arts, forms and subject matter. Unlike these regimes of art, the aesthetic regime brings about a breakdown of hierarchy invoking a redistribution of sensibility. The boundaries between genres also tend to dim as art acquires an autonomy in which disparate forms and genres come together.

The political as a qualifier of Navjot Altaf’s works and practices is of this nature, in which there is an endeavour towards an aesthetic regime of art, alongside ethical and representational regime. And following C. W. Mills, the political is not bereft of the personal, just like there is no disjunct between biographical and historical. Such epistemological combination aids in understanding the distinctions of service-in-collaboration in Navjot Altaf’s work.

Subjectivity of Navjot Altaf

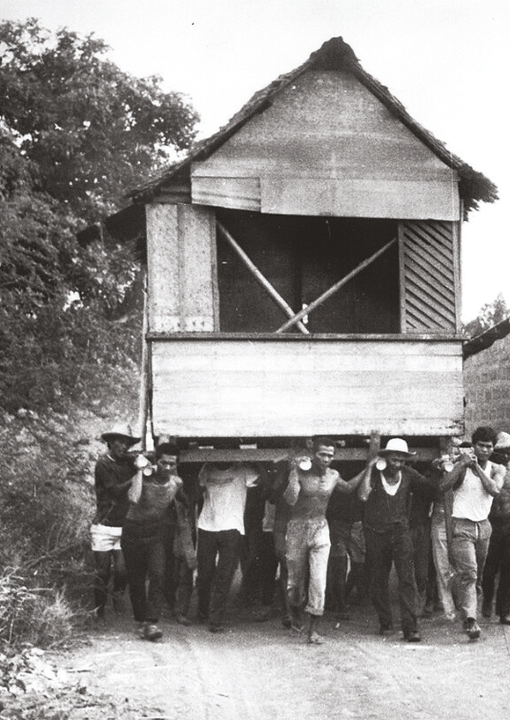

One often refers to the Curriculum Vitae (CV) when asking ‘Who is the artist?’ The CV approach to an artist is useful for a quick understanding about their affiliations and achievements. But there is also a thick narrative buried in a CV that alludes to the formation of an artist’s subjectivity. Consequently, the key question is not ‘who is Navjot Altaf?’; instead it is ‘what is the artist’s subjectivity?’ The second question solicits an interpretative rather than a CV-based approach to an artist. To answer the question, what follows will seek and consider a few key instances from a publication by The Guild3 titled Artist’s Notes, in which Navjot’s body of works appears and which will aid to comprehend what shapes the ways of seeing of the artist.

Artist’s Notes

Credit: Navjot Altaf

Navjot acknowledged that her mentors, the internationally acclaimed artists such as Akbar Padamsee and Tyeb Mehta, exposed her to the readings on aesthetics and anti-aesthetics. This was an advent of the inclination to broaden the discourse that envisions arts as liberated from the conventions of aesthetics. This would include Navjot’s perpetual dialogic relation with the rest of the world of art and activism, academics and politics, civil society and communities. She engaged and incorporated the ideas and insights into visual art, interacting with theorists, feminists, lawyers, filmmakers, scientists, musicians, environmentalists, psychoanalysts and so on. Art and life became conjoined twins, nourishing each other. This also meant that she navigated the landscapes of cities and beyond, in dialogic relationship. Navjot noted the objective of such navigation as she aspired, “to breathe the same air and take in the same sights, and in so doing, blurring the division separating art from life.”4 As a result, a unique framework of collaboration with a sense of organicism arises. The distance between the self of the artist and that of the ‘other’ tends to get minimal in the collaborative framework of Navjot. The ‘other’ was an oriental construction for many anthropologists of the 20th century in response to the colonial regime of power.5 The oriental other was a source of awe and horror that anthropologists sought to document, and the state aimed to control. An artist such as Navjot was inclined to collaborate with the communities to remove the orientalist impositions.

The indigenous community, that is experientially distant from the city-dwelling artists, is an integral part of the artworks and art practices of Navjot. And how is it accomplished? A deep sense of empathy, something that may appear as a technical Verstehen for a sociologist following Max Weber6, is also central in Navjot. However, there is a qualitative difference. A sociologist may employ Verstehen without sufficient immersion in the social and political context of a community. Whereas, in Navjot’s practice empathy and understanding arises from a deep praxiological commitment. Although Weber’s sociology centralises the interpretative acts of understanding the social action, it did not acknowledge the divide between what we learn and what we practice. Praxis, as a Marxist thinker such as Antonio Gramsci7 had discussed, was a tool to aid in understanding the divide between theory and practice, and then accordingly, carry out actions which aim at the transformation of the world. Navjot’s subjectivity is characterised by such a praxiological understanding of the world in which theory and practice are intertwined. As a result, Navjot’s art practices could add more nuances to the technical usage of Verstehen.

She does not only work with the members from the communities. She tends to dwell in the same context as the communities with which she collaborates. In engagement with the contributors from the communities in collaboration, Navjot says:

working with and listening to them has been a process of learning for life and has made me deeply interested in the indigenous perceptions of the human-nature relationship. ‘Deep Ecology’ is what they believe in and I like to imagine how we can practice this awareness in the times we are in…what interdependences in interspecies and multispecies relationships mean, how we can imagine together a sustainable culture.8

This was reflective of a way of seeing that entailed due sensitivity, of ecology, to the depth of relationality between human and nature, and moreover, a sense of the personal. Personal sentiments were present in most of her art practice. This personal is, as underlined above, duly ontological in which self and other are not binary opposites. They come together to constitute the being of an artist.

The ontological subjective disposition of Navjot is vivid in her aesthetic outcomes. For example, her 1993 co-operative project with craftspersons, Circling the Square, questions the hierarchy between art and craft, artists and craftsperson. The divide of art and craft was akin to that between tradition and modernity. In the scopic regime of modernity, crafts were too subaltern to be part of the exhibitionist visual art. By questioning the hierarchic position of art and craft Navjot enriched a template that could reunite the two. The artists and craftspersons were co-creators in the spirit of service-in-collaboration.

This falls squarely within Navjot’s overall emphasis of ‘public-ness’ in contemporary visual art. Here is a broader notion of public that is not essentially confined to a class. A concrete example is the consistent collaboration with the indigenous artists and community members in Baster district of Chhattisgarh in India. The project sites were Pila Gudi and Nalpar and the project was completed in 2007. The Nalpar collaborative project emerged in interaction with the community that fetched water from the tanks, and constructions of drainage became part of the artworks. The aesthetic transformation of a gendered public site such as water tank stands testimonial to the relationship between art and public. Likewise, Pila Gudi, literally meaning ‘temple of children’, became a site for art workshops with children that resulted in artworks created by children of the locality. Such collaborative projects are goldmines for sociologists and social anthropologists of contemporary India. Navjot is not merely an individual artist in these projects. The artist becomes one of the actors of aesthetic transformations. To free the world of art from hierarchies imposed from above and sustained from within, there was an imperative to rethink the space of creating and curating artworks beyond the rigidity of professional spaces. And this also meant partnership with those who belong to the larger public-sphere, the civil society and other communities participating in the public.

Such ideas and inspirations shaped the subjectivity of Navjot and her engagement with the marginal. A multi-scaler, non-linear and assemblage format allowed her to deal with the manifold marginality. There is an uncanny subalternity that manifests in the marginal becoming mainstream with Navjot’s practice. However, she was not entirely dominated by the conventional Marxist way of seeing. There was an intersectionality of class and gender that appears to be an abiding feature in her subjective disposition. Therefore, what is the marginal is inclusive of categories that face deprivation. This is also because Navjot’s way of seeing was in a perpetual process of becoming. There is a characteristic radicalism of 1970s in her key questions, “who was art to speak for, how could art speak to/for ‘its people(s)’, and specifically to the working classes.”9 Navjot creatively responded to the age of radicalism, exploring alternative spaces, modes, and expressions. The explicit objective was to critically subvert the bourgeoise structure and ruling class ideology that controlled the art scene.

But then the economic determinism of Marxist theory had begun to stir a new quest among the artists. There was a critical awareness about the delimiting bipolar Marxist structure, of core and periphery, of base and superstructure. Art was only secondary to activism in such bipolarity. Moreover, there was only a limited way in which a Marxist framework allowed an artist’s engagement with the multi-scalar marginality. Not only class, but also gender had to be a locus of marginality. No wonder, an ever-evolving Navjot had to turn to gendered spaces, practices, and experience, away from the deterministic Marxist politics by the decade of 1980s. This was a leap forward in the politics of art, leading further to the deeper questions about the nature of democracy and public sphere. Navjot’s artistic subjectivities grew exponentially with praxis.

This small introduction to Navjot’s subjectivities helps to comprehend a non-monolithic nature of the everyday, the dynamics of ordinary experiences and an ever changing worldview. The art performs service-in-collaboration through the dynamic ordinary. As a result, the phenomenology of everyday, a point that the essay returns to in the following section, invites a sociological departure. On one hand, this is a departure from Alfred Schutz’s reworking of Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology10; on the other, this is a return to the feminist standpoint theorists who adopted phenomenology as a way of seeing. If the sociological phenomenology of Alfred Schutz was too abstract and a-historical, the feminist reworkings of phenomenology were to ensure the materiality of everyday life. The phenomenology of everyday life in Navjot’s works foregrounded historicism and materiality of women’s experience. More layers of Navjot’s subjectivities, with due phenomenological objectivity, surfaces when we turn to her specific works.

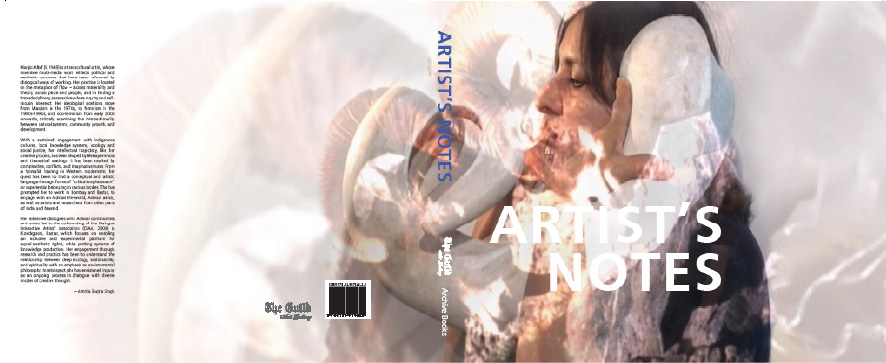

Navjot at Work

Credit: Navjot Altaf

Service-in-collaboration: Navjot at Work

The life and work of Navjot Altaf is subject to and invites a discursively enriched hermeneutics in which fluid associations and perpetual meaning-making are integral. A second publication, a three-essay book, Navjot at Work, with an erudite foreword and a photographic chronicle of her artworks and practices, accomplishes the imperative. With this book as a reference, in examining the organic collaborative works of Navjot, the following is an attempt to aid in the understanding of the nature of service-in-collaboration, in which the meaning of service acquires sociological depth, as stated at the outset of this essay.

Underlined in the foreword of the book by Gita Kapur, and reverberating across the essays, is a fulcrum—Navjot Altaf’s being and becoming, ideas and practice, implications and outcomes that constitute a ‘phenomenology of sensible experience.’ This is a phenomenology in which the idea of Rancière, discussed at the outset, finds a concrete expression. The phenomenological construction of an aesthetic regime that performs a politics: a reformulation of the sensible experiences that is central to Navjot at Work.

Typically, phenomenology is the art and science of subjective meanings leading to a deep hermeneutic understanding of the everyday worldview. Navjot’s ordinary worldview, in the essays in the book, approaches a hermeneutically loaded phenomenological episteme, which is the everyday! ‘Everyday’ as an experiential category is not merely a spatial entity. Instead, it solicits our romantic utopia and critical rationalism at once, which paves the way for a creative being on the historical timeline.11 Navjot’s aesthetics and ethics transform the everyday into an experience of possibilities. In such a framework of everyday life, the ordinary is accessible to those who join in an aesthetic-ethical-relational reasoning. The artists and those who are seemingly outside the realm of art tend to become one. The sense of aesthetics, ethics, and politics become intertwined. And therefore, Nancy Adajania’s remark elsewhere holds meaning for the larger oeuvre. She noted:

Navjot’s meditative video-poem returns grace and dignity to the figure of the artisans, not by creating a “work of art”, but by reflecting consciously on the act of labour itself. This lyrical account has a philosophical density that will outlive an anthropologist’s limited scrutiny, a developmentalist’s weakness for value judgment.12

Interpretatively, such philosophical surplus emerges from Navjot’s uncanny wandering through the humans and non-humans, sensorial-experiential, conceptual-philosophical and political-praxiological, inter alia. Adajania’s critical acknowledgement of an anthropologist’s limitation is duly suggestive. More than the visible, the said, and the noted, there are layers of practices that originates from everyday life embedded in Navjot’s practices. As noted above, the public-ness of the collaborative art projects shall be seen as integral to practice-based everyday life in Navjot at Work.

Precisely, this challenge to an anthropologist’s limited scrutiny was hinted at the outset of this essay. The challenge is not merely about decoding the philosophical density in Navjot’s artworks. More than that, this challenge demands from anthropologists and sociologists an acknowledgement to the nuances in the idea of socially organic collaborative practices which offers more than Durkheim’s idea of organic solidarity. The template of service-in-collaboration is fraught with the surplus arising from the everyday, the ordinary, and the ontological. In Navjot’s art practice vis-à-vis collaboration with ‘others’, there is an emotionally dipped intellectual interest, rather than a linear utilitarianism. The affect of collaboration, due to its praxiological tenor, collapses manifold binaries. This becomes a premise for an artist’s services to the social world. To substantiate it furthermore, the following is a synoptic rumination on some of the artworks of Navjot.

To reiterate a point, the personal, an embodied experience, is the Siamese twin of the aesthetics and ethics in Navjot. Desire, intimacy of sensation, erotic fantasy transpire in the non-linear narrative, the fragmented script.13 This is somewhat to suggest a homology between the personal and fragmentation. Arguably, only a fragmented script could be conducive for the expression of the personal that is subjectively routed and ontologically tied to experiences. Such personal dispositions lead to unearthing and engineering novel possibilities when works open up ‘subjectivised space of the political’. This is not the conventional and familiar politics articulated in the lines of a political party or in a political slogan. Instead, the subjectivised nature allows the political to be tightly aligned with personal and public at once. Hence, Navjot’s art practices aim at critically dissecting various avenues of being and doing. Circling the Square, referred to earlier in this essay14, added a spin to the idea of public art. This motive continued to unfold nuances in the latter works of Navjot. The artwork, that brought the elements of craft closer to visual art, redefined art practices and made space for more elaborate assemblage.

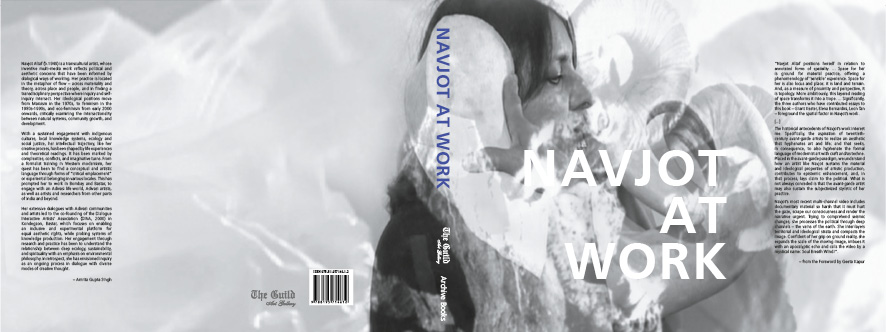

Links Destroyed and Re-Discovered (1994).

213 x 975 x 1067 cms. Installation with sculptures, photographs, films & music. Rendered image.

Credit: Navjot Altaf

This found more radical articulations in Links Destroyed and Re-Discovered (1994). An immaculate assembly work, Links included two documentary films, Bombay: A Myth Shattered by the activists Teesta Setalvad and Madhushree Dutta’s I Live In Behrampur. The Bombay film documented the aftereffects of the 1992-1993 riots in Bombay. The film narrated the anguish of the community about the frayed inter-community relationships in an erstwhile cosmopolitan Bombay. Dutta’s Behrampur was a more sociologically informed unravelling of a Muslim ghetto that was a target of negative portrayal by mass media during the riots of 1992-1993. The citizenship of the depressed class of Muslim population living in the suburb Behrampur was a key casualty during the riots. The two moving videos were accompanied by an equally affective musical composition. The classical Hindustani vocalist Neela Bhagwat sang the medieval saint poet Kabir’s couplet, Sadho dekho (witness saint). The installation work sets a new dimension to the collaborative artmaking. Once again, with the personal in the backdrop, the installation divulged how “having to redefine one’s identity in one’s own country was a traumatic experience.”15 Using historical consciousness the work capitalises on the memory and affect of violence and trauma. Navjot noted:

The 1947 partition of India and Pakistan killed thousands and displaced millions, including my parents. Even today while listening to them or other survivors who went through this traumatic experience, recalling the events, one realises that this is a past that refuses to go away.16

The artist’s preoccupation with the traumatic experience made her connect the series of catastrophic violence in post-independent India, riots following the demolition of the Babri mosque in 1992, spates of violence conducted by the fundamentalist forces. At every instance of violence in post-independent India there was an artist as a witness. What happens when an ontologically located artist is a witness to the violence? Artist as witness has been a useful conceptual lens in the 20th century to comprehend the essential relationship between art practices, artworks and experience of violence. The role of art as a witness to ‘what/which is’ may be traced back to existential philosophy, and the name of Martin Heidegger surfaces for attention. Art and Dasein (broadly being) were connected in existentialist hermeneutics. By and large Radhakamal Mukerjee, mentioned at the outset of this essay, gave the existential Dasein a sociological name—social structure. Artworks were witness to dynamics of social structure in post-independent India. However, the idea finds more concrete expression in the collective and collaborative art projects of artists, activists, and academics. The artists’ collective across the globe have been keen to establish artist as witness, and thus artworks as testimonials of the time. Artist as witness, arguably, becomes an essential feature of artists’ service-in-collaboration.

A video grab from Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness (2017).

Credit: Navjot Altaf

The idea of an organically emergent collaboration, in which self and other joined hands, reached another zenith later in 2017 with Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness. The project entailed a mock trial directed by Zuleikha Chaudhari in collaboration with Khoj International Artists’ Association.17 The project work was a staged hearing before the Commission of Inquiry under the Commission of Inquiry Act-1952 involving lawyers Arpitha Upendra and Anand Grover. In the staged hearing, the artists who appeared as witnesses were Navjot Altaf, Ravi Agarwal and Sheba Chachi. Critically reflecting on the river linking project and the devastation caused by it, the trial aimed at:

reinterpreting the language of the law through art, by positing that contemporary art is capable of inventing creative and critical approaches that analyse, defy, and provide alternatives to reigning political, social and economic forms of neoliberal globalisation.18

Every word of techno-legal significance became a personal and experiential allusion in the project. The collaboration itself became an emotionally and intellectually pertinent ground for a sense of service to the society. Navjot provides a concrete example of how an artist as witness can participate in the issues that connect environment, justice and citizenship, and thereby serve as a chronicler of experiences. The project had the artist-witnesses categorically asserting:

I want not land for land but a running brook for a running brook, a sunset for a sunset, and a grove of trees with shade for a grove of trees with shade. So my right to life is a right to my specific civilizational mode of being in the world. And I cannot be rehabilitated or compensated outside a recreation of what life means to me.19

An artist as a witness tends to infuse her personal longing, aspirations and emotions into the public concerns. Her poetry and politics come together as she speaks on behalf of the affected humanities. Thereby as a witness, the artist connects biography and history, personal and public. As a witness, Navjot, is in all of her works, telling us, the reader of subjective histories, about some of the burning issues as well as about something closer to humans in everyday life. About Rethinking Stereotype, an interactive installation with film posters in 1997 that questioned objectification of the female body, Navjot said:

During the process of drawing or sculpting a female form, I as a woman become extremely conscious of each part or contour of the body, literally escorting it from becoming an object of display, to where the body becomes a potent source of gesture, an instrument of resistance.20

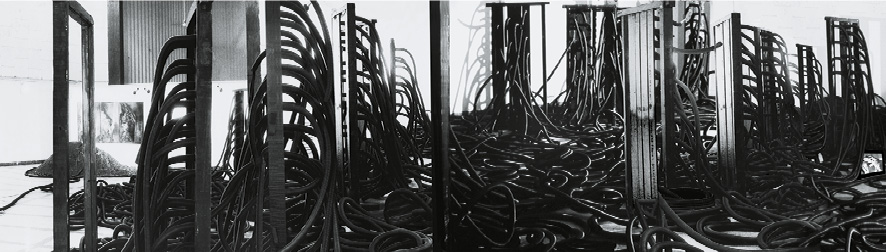

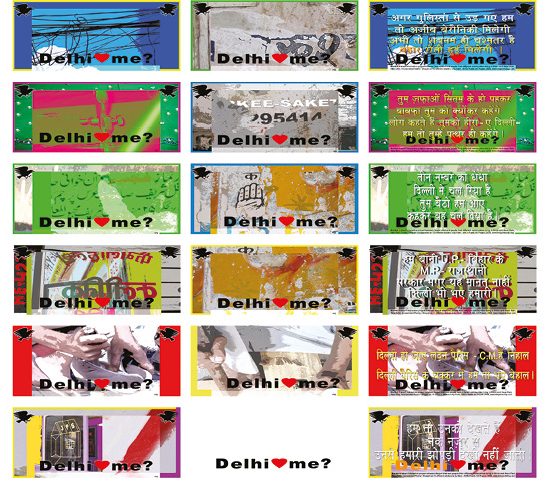

Another example of a direct encounter with the public was the art project, Delhi Loves Me? (2006) by the Khoj International Artists’ Association. The project was a riposte to the text on popular stickers, ‘I Love Delhi’ in the time of the transformation of the city-space by the Delhi Government. Delhi was subject to a beautification in preparation of the then-forthcoming Commonwealth Games. The project was a critical response of the artist to the eviction and demolition of settlements of the poor. The migrant workers of the city were worst hit in the wake of then ongoing attempts to make Delhi ‘lovable’.

In many such works the aesthetic-ethics encores the re-visiting of spaces in which flora and fauna, humans and animals, animate and inanimate, spectacular and banal interact—within the modern grid.21 Navjot’s personal is still central, as she discovered the presence/absence of trees in the burgeoning concrete jungle of Barakhamba (2010). Semiotic values of the mundane and magnificent, the containers and the river in Empty Containers (2011), reaffirmed the artist’s sense of service to the society. An analogous relationship of the city and human anatomy in Body City Flows (2015) made spatial embodiment a central idea. Above all, there was a telling semiotic-praxiological centrality of the Mahua tree, known as the tree of life amongst the adivasi22 of Bastar in Politics of 100 Mahua Trees (1999). There are metaphors through which Navjot re-turns to the known and unknown without slipping into nostalgia or making a compromise on the humanised-historicised hermeneutics. Hence, interpersonal relationships and consequent subjective experiences dominate in a long series of works that centralises an ontology of the ordinary lives interspersed with meanings and fraught with inexorable meaning-making. Navjot at Work thus becomes an essential reading for sociologists and anthropologists longing for the avenues to explore theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and philosophical advances in a post-positivist world.23 Navjot’s body of work provides ample space for sociological reasoning in which ontology supersedes epistemology.

Delhi Loves Me? (2006)

Credit: Navjot Altaf

Autorickshaw with a sticker on it, from Delhi Loves Me? (2006)

Credit: Navjot Altaf

In such a backdrop the three essays in the book Navjot at Work enable a conceptually sound interpretative engagement with Navjot.24 Art historian Elena Bernardini chronologically locates the emergence of public space and community as a focus in the intellectual and personal biography of an artist. A point made earlier, there is a hint of sociological imagination in the relationship between Navjot’s biographical trajectory and historical encounters. Bernardini aids in comprehending the meeting of micro and macro in a dialogic aesthetic.25

With an exposure to Marxism, Navjot had started critically rethinking the elitism of the art world in the 1970s that enabled her and other artists to evolve “ways of working and exploring art as a means of community outreach and politicisation.”26 There was however a critical realisation of the inherent limitations of Marxist lens in the 1980s. This led Navjot towards alternative epistemologies to unearth the depth of engendered marginalised subjectivities. The biographical and historical experiences advanced furthermore. In the wake of neoliberal globalising and mobilisation of the communal politics in the later decades, Navjot began to sharpen her aesthetic lens at other questions. The question of public became intertwined with that of democracy in the politically volatile India.

A perpetual negotiation between art and activism27 comprising tension and reflexivity seems to have shaped up Navjot’s interventions. Grant Kester’s essay notes as emerging key aspects: “adaptation and survival, resistance and assimilation.”28 These aspects characterised her decade-long engagement with the collaborators amongst the adivasis in Kondagaon, Bastar in Chhattisgarh. It led to the formation of Dialogue, a centre of art practices, collaborative and immersive processes, and moreover, a trail of what may be safely called ethnographic-art. The Nalpar sites, mentioned earlier in this essay, created structures around handpumps in order to make an intervention in the seemingly mundane gendered space. The project had far more profound implications than NGOs’ developmental schemes. In this process, Navjot’s art practice manifested a hermeneutic ‘fusion of horizon’29, paving the way for a re-creation of the everyday life, adding a new fillip to the phenomenology of the ordinary.

Foremost in such an endeavour lies a challenge—the idea of the ethnographic embedded in conventional anthropology. Foster, in The artist as ethnographer?30 had discussed the potentialities of artists as ethnographer. The objective was to underline the relationship between art, anthropology, and politics of representation. Foster was keen to show that an artist as ethnographer is more equipped to bridge the gap between the self and other. This is unlike an anthropologically trained ethnographer who maintains a sense of distance from the object of enquiry. The idea of artist as ethnographer was central in Dave-Mukherji’s31 unraveling of the ethnographic disposition in the art practices of the artist Pushpmala.32 Such ethnographic art practices hold out a great opportunity for the anthropologists who anxiously debated the nature of ethnography in anthropology.33 An artist, as an ethnographer as well as a witness, is indeed more inclined to render the outcome that qualifies for service-in-collaboration. Such an artistic ethnography is not a technical documentation of the observed objects. Instead, the documentation in a collaborative framework puts together self and other, the artist and the community. Furthermore, the coming together of an ethnographer and a witness in the artists augurs well for a socially rooted and politically responsible art practice.

In Navjot at Work, Leon Tan’s essay comes headlong with provocative postulates. The essay reminds us of the reductionist nature and scope of available theories in social and cultural studies. Theories with suffixes such as structural, functional, realist, positivist, behaviorist, poststructural, interpretative, seek to reduce art practices and artworks. Such theoretical strands allegedly lead to the three broad labels of reductionism, namely, microreductionism, macroreductionism and mesoreductionism. And hence, as Tan arguably suggests, ‘assemblage theory’ is most appropriate to comprehend Navjot’s works and practices that deal with multi-scalar reality. Such a reflexive theoretical approach aids in understanding the sensorium underpinning and consequent upon Navjot’s practice. Many verbs such as listening, immersing, talking and, overarching these, ‘be-ing’, amount to a more processual arrival at a series of nouns. The coming together of verbs and nouns in the grammar of an artist evokes a sensory totality, an ontological sensorium! The network of collaborations give birth to a kind of relational aesthetics in which encounters of disparate assemblages is foremost. This is somewhat characteristic of the aesthetics of the service-in-collaboration.

However it is this very processual uncertainty, a kind of fluidity of the being of the artist, which renders the art practice of Navjot into an organically evolved praxis.34 In this praxiological scheme, being and doing, thinking and feeling are hard to separate. Any endeavour to impose a conceptual framework on the processual praxis diminishes the hermeneutics entailed. Attempts to define the ordinary and conceptually classify the ontologically complex embodied personal experience, the core of Navjot (at) work, perhaps may give rise to the conceptual binaries!

Conclusion: Sociology of Contemporary Visual Art

This essay is an attempt to underline the significance of Navjot Altaf’s art practice, with reference to selected works, to comprehend the key theme—service-in-collaboration. The nuances of the service surfaces in an analytical engagement with the art practices and work of Navjot in this essay. The double-edged appearance of an artist, as an ethnographer and a witness, tend to infuse more value into the notion of collaboration. The distance between the self of an artist and the objects of representation shrinks. There is no oriental or contemporary other, in the art practice of Navjot. The artworks thus are social, cultural and political at once.

A constant refrain in the essay is the imperative for sociology and social anthropology in South Asia to turn to the visual arts and practices. Engagement with visual arts in contemporary sociology in the region of South Asia and particularly in India is few and far between. Volumes of visual arts engage with objects of enquiry that are seemingly sociological and anthropological. The pioneers of sociology, as alluded to in this essay, envisaged a sociology in post-independent India that could read arts in order to develop a social hermeneutics. Somehow, it has been buried in ‘disciplinary amnesia’, a lament that has been echoed by some contemporary sociologists.35 Moreover, the relation between sociology and art forms was critically emphatic in the global American sociology too. Robert Nisbet was a prominent proponent who underlined this relationship in the classical sociological theories. The sociological reasoning in this essay, for example, dwells on not only sociological-theoretical premises but also on the ways of making sense of the arts and aesthetics. Hence, the idea of aesthetic regime that plays a crucial role in the political nature of relationship between the self and other is foregrounded. There is a perpetual urge in Navjot at Work to dislocate and relocate her art practices, in public with public at large. A redistribution of the aesthetic sensibility upsets the politically sustained order and hierarchy, adding a critical feature to the service-in-collaboration.

This essay, dealing with the artworks and art practices of Navjot Altaf, explored as to how novel possibilities for sociology and anthropology could emerge. Be it in terms of the methodological tools or the ways of seeing that an artist such as Navjot employed. The emergence of conceptual lenses is equally significant. There is an under-explored epistemic density in such a visual art practice awaiting sociologists’ attention. A novel sense of artist’s ethnography, a socially and politically enmeshed art practice, arises in Navjot’s oeuvre that cannot be easily ignored by the anthropologists who claim to be champions of fieldwork. In such a context, a phenomenological episteme, the everyday, becomes a potent rationale for revisiting the classical texts too.

This essay has tried to modestly accomplish a sociological comprehension of the praxiological everyday, and consequently a notion of service-in-collaboration in Navjot at work. The everyday is historical and material as much as it stands for the poetics and politics of the ordinary. To emphasise, the service to the social world by artists in an organic collaboration is not a utilitarian, agenda-driven, short-lived project. Instead, it is a more elaborate structure of organicism in which service is as much personal as it is public, corresponding with the nature of public art. In the same breath there could be further sociologically inclined interdisciplinary explorations of the interface of market, state, society and the world of visual arts.