Aperitif

Hear no evil, speak no evil, and you won’t be invited to cocktail parties. —Oscar Wilde

Since this journal edition is dedicated to Tropical Lab and its name will reoccur, for the sake of variety and comic effect I am taking the liberty of retitling it ‘Cocktail Lab’. The annual international art camp brings together around 25 gifted postgraduate students flown in from all around the globe, and operates for its participants like a heady cocktail. Landing at Singapore’s Changi Airport, giddy and jetlagged, and for some their first ever flight, Cocktail Lab provides a potent mix of ingredients that come together in delightful and surprising ways, with effects that are intense and intoxicating.

It was founded by Milenko Prvački specifically as a ‘laboratory’, where experiments take place and, traditionally, chemical compositions are mixed together in large glass jars to create mysterious new potions—precisely how cocktails are made. Mixology, the art of combining different drinks to concoct a cocktail, is highly fashionable nowadays. Singapore boasts some of the world’s finest bars, where mixologists continue the furtive traditions of their medieval alchemist predecessors in hidden underground laboratories. As Peter J. T. Morris recounts, while these ancient alchemists ran secret lairs filled with furnaces and bizarre contraptions, chemistry was the first noble science to be openly afforded a room of its own; the histories of laboratories and chemistry are inseparable.1

There are some notable differences between alchemy and cocktail mixology, not least the former’s quest for magical, real-world transformations of matter. But the most dedicated mixologists may argue their goals are the same, and that they share a quasi-mystical devotion in seeking to create potions that are (or at least taste) miraculous and transcendental.

The Getty Research Institute’s 2017 exhibition The Art of Alchemy explored the close links between alchemy and art, and highlighted that important inventions originally born from alchemist laboratories range from oil paints to metal alloys for sculpture, and photography’s chemical baths. Its catalogue reflects insightfully on their common themes:

Long shrouded in secrecy … Alchemists were notorious for attempting to make synthetic gold, but their goals were far more ambitious: to transform and bend nature to the will of an industrious human imagination … unlocking the secrets of creation. Alchemists’ efforts to discover the way the world is made have had an enduring impact on artistic practice and expression around the globe. … [It] transformed visual culture from antiquity to the Industrial Age, and its legacy still permeates the world we make today.2

Alchemists at work, from Mutus Liber, a ‘Mute Book’ of illustrated plates

(with no written text), 1677.

The mixological trial and error nature of both chemistry laboratories and cocktail creation is key to Prvački’s vision and methodology. He tries to get the chemistry right, by liaising with the Professors at partnered institutions to choose one postgraduate student who is ideally suited to the experience. Not their ‘best’ student necessarily, but an interesting one with something to say and share, and someone who wants to share; not a loner or worse still an egotist, but a companionable and convivial giver. Personality, enthusiasm and collegiality are key to the ‘Milenko Mix’. Once chosen, these creative ‘spirits’ from different countries are intertwined, and collaborate together under his guidance. He encourages them, like the alchemists, to discover and experiment with new ideas, ingredients, concepts, tools and media; to think afresh about the world, and to work outside their comfort zones.

To return to cocktails, mixology’s interplays with powerful chemicals renders it a laboratory process fusing the arts and sciences. Like with art, some excellent creations come about in eureka moments, the product of luck, instinct, inspiration or a muse. But others are hard won: the product of rigorous reworking, like Frank Auerbach’s paintings, its thick pigments applied and scraped off, then reapplied and scraped off again, endless times over months or years. Mixologists seek perfect formulas in much the same way as chemists. But perfect formulas are not as rare as you might think in cocktails. Books on the classics reveal hundreds and thousands of them, and with some creative adaptation and improvisation you can make up some delicious originals yourself.

There is a second reason why I will dub the art camp Cocktail Lab: my main contribution to the annual gatherings is to invent cocktails reflecting the year’s chosen artistic theme. These are mixed and served at a cocktail party for all the participants, hosted by my wife Prue and I at our home. It is held on the eve of the exhibition that marks the climax of the fortnight’s activities, when the students have finished all their work and can let their hair down. They arrive in a gaggle, the wide-eyed young artists, their sarongs tied in wayward and irregular ways, leaving shoes in an abandoned pile. First orders, laughter and later…dancing.

For the price of a beer in Singapore…

I was never interested in cocktails until I came to Singapore. But 10 years ago, I arrived here for the first time in my life for an interview to be President of LASALLE College of the Arts, and stayed in a nice hotel. The interview went well and as dusk settled, I went up to sit by the rooftop pool and looked over glittering Marina Bay, thinking “I’ll have a beer.” On consulting the menu and the price, I fell off my chair. But on remounting, with stoic determination to have a drink nonetheless, I was fascinated to learn that for just a few dollars more I could get a champagne cocktail. It tasted magnificent, and with such price differentials, I’ve rarely drunk beer here again. Therein began a fateful love affair with two things that remain precious joys: LASALLE…and cocktails.

Cocktails have inspired many artists, including writer Ernest Hemingway who created a devastating one, Death in the Afternoon (1 part Absinthe, 3 parts champagne) and helped invent the best ever version of a daiquiri cocktail (2 white rum, ½ maraschino, ½ grapefruit juice, ¾ lime), which is named in his honour.3 But in celebrating cocktail consumption I must also sound a serious cautionary note on the need to act moderately in doing so. Famously, alcohol had a devastating effect on Hemmingway’s life and familial relationships, while Jackson Pollock perished as a drunk driver aged 44, and historically too many artists and non-artists alike have been victims of alcoholism.

In 1932, novelist and playwright Jean-Paul Sartre had an epiphany with an apricot cocktail. He was drinking it in the Bec-de-Gaz, a bar on Rue du Montparnasse with his friend Raymond Aron, who was enthusing about a new philosophy. “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” he declared, and Sartre literally turned pale.4 He gave up his teaching job, pored over phenomenology books and within a year had come up with his own version: existentialism. It was grounded in the phenomenological reality of life while seeking a type of transcendence from it through individual freedom, self-determination and originality—messages worth considering for any young artist:

There is no traced out path to lead man to his salvation; he must constantly invent his own path. But to invent it, he is free, responsible, without excuse, and every hope lies within him.5

The Cocktail Lab party drinks I create and serve (at my own expense, I should add) are hopefully existentially free and original, and include some that surprise participants with equal delight and horror. For the theme of Port of Call in 2014, for example, came the following concoction with ingredients in relative measures:

enDURIANce

3-inch piece of Durian fruit

2 Tequila

1 Spiced Rum

dash of Grapefruit Bitters

Put ingredients into an ice-filled shaker, shake and strain

For the Island theme in 2015:

Isles of Hallucination

¼ Absinthe

1 Lychee liqueur

1 Pernod

½ Dry Vermouth

2 Wheatgrass juice

Stir with ice and strain, then

top with a little lemonade

While the theme of Fictive Dreams in 2016 brought with it, topically

BREXIT Nightmares

Sour grapes

2 Black Cherry Vodka

1 Gin

3 Cranberry juice

½ Gran Classico

¼ Lime Juice

Serve with ice in a metal, prison-style cup and garnish with a piece of old, dry white bread, to visually reflect the probable consequences for the British economy

One drink that always remained on the menu was a tribute to the ‘Tropical King’—an affectionate nickname bestowed on the Lab’s founder and chief. Its ingredients were the same—as shown here—but its name changed according to the year’s artistic theme: Pulau Milenko, Milenko Memories, Milenko is a Dreamboat, etc.

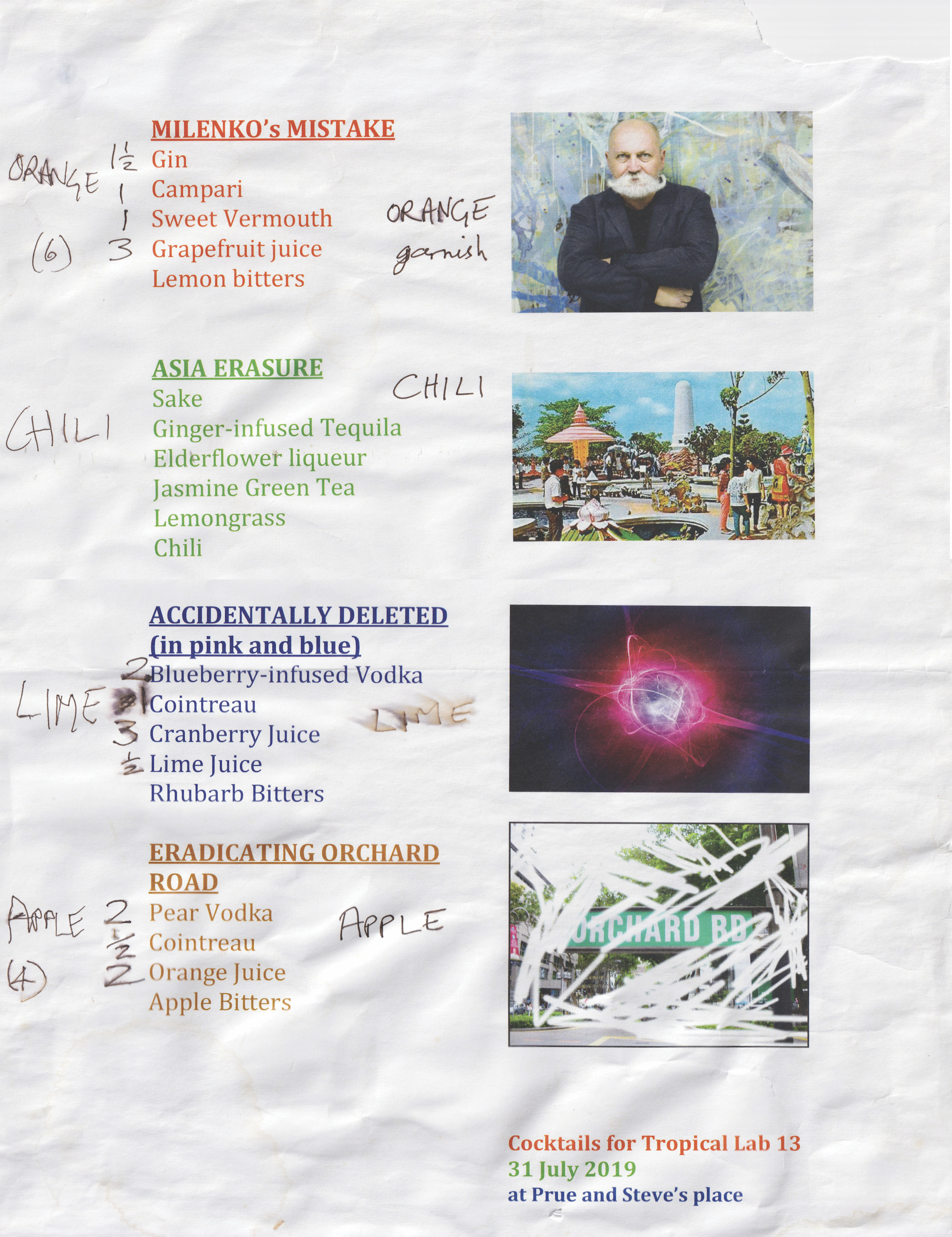

Photo by Steve Dixon

The ‘behind the bar’ menu, with scribbled reminders of garnishes and ratios of

ingredients, for the Erase 2019 cocktail party. Asia Erasure lacks ratios as it had

been pre-mixed and infused for six hours with chopped pieces of ginger and

lemongrass. For reference, its ratios were: 2 Sake, 1 Tequila, 1 Elderflower liqueur,

3 Green Tea, ½ Lemon juice: serve on ice with a slice of red chilli.

Mixology and Metaphors

As part of the wider cocktail mix, every year the Lab took a different theme as a point of departure and source of inspiration. A theme can be interpreted literally, in concrete ways, but the guidance given, and the tendency with which the participant artists were to use it, was more metaphorical, associative or abstract. Each theme also provided food for thought for me, to reflect upon in preparation for speeches I would make either to welcome the throng or to launch the opening of their final exhibition.

Most of the themes are simple single words, but they hold much power and provocation, providing a small kernel from which grander things will grow; as Nicholas Cook notes, “Words function as…[art’s] midwife.”6 The topical words provide a sense of focus, harmony and unity for the participants. But they are also mixological, since each student’s expressive transmissions and individual translations of them reverberate and resonate with one another in unexpected and sometimes contrary ways. Like the process of inventing cocktails, exploring themes leads to free associations and proliferations of ideas, and I’ll now offer some of my own about the year-by-year topics and the idiosyncractic results they inspired.

Echo 2013

The 2013 theme brings to mind the echolocations of bats and submarines—which send out signals and sonar pulses that bounce around, and then resonate back. The signal returns transformed, in a slightly altered form, which reorients the understandings and perspectives of the receiver. Cocktail Lab works in the same way. Students are sent out from around the world and arrive at LASALLE where they bounce around, colliding with other things: new people, places, objects, experiences, ideas. They then return from whence they came, transformed (we hope), in a slightly altered form, and with new bearings and viewpoints.

Their artistic projects responded to the Echo theme with great vision, offering up vivid explorations, including subtle plays on ideas of translation and doubles. They worked from many angles: visual, aural, textual, conceptual. The contributing writers to the accompanying ISSUE journal edition responded to the theme equally memorably. Darren Moore mused on echoes in music as “a continuum of practices and belief systems” activating improvisation, re-contextualisation, adaptation and evolution7 while Venka Purushothaman evoked Walter Benjamin’s comparison of an echo heard in a forest to the notion of translation:

the echo is not the original sound, and the copy not the original. To investigate this, we need to resuscitate the flailing nymph Echo pining for the love of Narcissus, and one has to return to the primordial scene: the sighting.8

Port of Call 2014

Port of Call prompts considerations of destinations that may prove lasting for the visitor but are more likely to be fleeting: sites of transit. Used colloquially, a port of call may be anywhere, including somewhere landlocked, but the idea of a nautical port catalysed research on Singapore’s longstanding position as an international trade hub. The Lab was given special access for an excursion into the heart of Singapore’s container port, one of the largest in the world. It was an extraordinary foray into a dense, seemingly endless labyrinth of stacked steel boxes and looming giant cranes, a monumental metal maze of geometric grandeur. The Italian Futurists would have loved it.

Space and time are intimately connected, indeed insoluble, and ports of call are transitional places experienced in between other places at in-between times. In a seminar I gave for The Lab I discussed how we may experience a different temporal sense in such spaces, as we do during long transits in port-of-call airport terminals where time seems simultaneously achingly absent yet thunderously omnipresent—the ‘extratemporal’. This sense of being and living outside-of-time is what anthropologists describe in relation to ancient and primitive cultures that do not recognise time in relation to the micro-chronologies of clocks, but rather the macro-chronologies of larger cycles: diurnal sunup to sundown, phases of the moon, the seasons etc. Aesthetic sensations of the extratemporal can be deeply affecting, and have been explored by artists in different ways. Think of the temporal manipulations and repetitions of Ho Tzu Nyen, the slowed down films of Bill Viola, Douglas Gordon and Urich Lau, Cornelia Parker’s exploded garden shed, frozen in time and floating eerily in space—each conveys an experience of placement outside of time.

Ports of call may prove magical places, crossroads that change lives. The sense of dislocation, transit and extratemporality can lead to an awakening return to oneself, or spark new creative inspirations and personal directions. The Port of Call that is Cocktail Lab has prompted many of its artists to be struck by the muse, to think anew and to reinvent their ideas or themselves: “out of reflection we receive instruction.”9

Island 2015

The 2015 edition interrogated the nature of islands, including field trips to the lush island charm of Pulau Ubin as well as Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, at the watery fringes of the isle of Singapore. Islands are separated by, yet inseparable from, water. Water gives permission to land. It surrounds and contains, and island dwellers are drawn to their land’s edge to marvel at it, relax, bathe and cast their gaze on it. They stare out to the flatness of the horizon, the seeming meeting of ocean and sky, two great unknowables. This watery-air meeting place is distant and yearning-filled, illusory and ungraspable—an end of a rainbow that can never be reached. The actuality of an island is its placement within a surrounding territory that is not actual, but virtual: its circle of horizons.

For islanders, to leave terra firma and set sail for the horizon is always a leap of faith and voyage toward the horizon of the unknown. There is no beckoning bend in the path, no receding perspective, no forest to cut through nor mountain to conquer. It is a challenge for both body and spirit to set sail towards and beyond nothingness. Oceangoing always holds risks, but artmaking holds similar, if not so mortal perils. Artists cast their gazes into the distance, drawn to unknowns and uncertain places.

“No man is an island” wrote John Donne, and a lone traveller reaching an island’s edge can go no further alone: the seashore marks the limit of the walking body’s capabilities, and humans are ill-adapted to swimming very far. To go forward the help of others is needed and, for islanders, leaving home is a task best managed as a joint undertaking. Preparations are made: a boat is built, a crew is mustered and plans are mapped.

For most artists too, the quest is not a lone one, and the Lab ensures the emerging artists work, play and learn together, nurtured and supported by extraordinary professional artists whose expertise make their journey memorable. Island people since ancient times have been proud to honour their visitors through codes of hospitality, and LASALLE is very proud to continue that tradition.

Fictive Dreams 2016

John F. Kennedy helps us segue from 2015’s horizon-gazing into the fictive dreams of 2016:

The problems of the world cannot possibly be solved by skeptics or cynics whose horizons are limited by the obvious realities. We need men who can dream of things that never were, and ask why not. [10. Kennedy 1963]

He spoke the inspirational words on 28 June 1963 and two months later to the day, Martin Luther King Jr answered the call with the greatest speech of all time. “I have a dream,” he kept repeating, in a stirring mantra announcing a transcendent vision of equality and freedom. It remains as crucial and urgent a dream as it ever was.

Dreams are one thing everyone has in common; they bind us together, and Shakespeare insisted we are made of the very “stuff” of them. They can be experienced while asleep or envisioned while awake. Dreams are endless repetitions not only of our own, but the collective subconscious. Like great art, they express and embody our unique and individual personalities while simultaneously expressing universal ideas, hopes and fears. Dreams are profound, confused, fragile and scary expressions of what it means to be human. They conjure the darkness and light of life and death.

Artists have explored them for millennia, from the Byzantine depictions of Jacob’s Biblical dream of an angel-filled ladder bridging heaven and earth, to the seductively beautiful but ominously sinister dreamscapes of surrealists Giorgio de Chirico and Paul Delvaux. Lucy Powell has observed that “Like a dream, art both is and isn’t true. Both offer a challenge to the tyranny of realism, replacing what is with what might be. Both generate an altered state of consciousness removed from the humdrum–and both lend themselves to interpretation.”10

All dreams are fictive dreams and all dreams are real. Somnambulantly, we reach out into the ether to commune with fantastical worlds and to drown in the oceanic imagery of our imagination. We freeze time and traverse space. We dream alone, yet we all dream together; let’s try to dream more beautifully and lucidly. As Jorge Luis Borges asked:

Who will you be tonight in your dreamfall

into the dark, on the other side of the wall?11

Déjà Vu 2017

The theme of Déjà Vu reached out for the capricious—that strange sense of a return or re-experience, and that paradoxical feeling that some place or thing is eerily familiar and half-remembered, yet finally elusive, ungraspable. I recall the final exhibition encapsulated exquisitely these complexities around the palpable but indescribable. When we’re struck by déjà vu, it’s a kind of revelation: a startling flashback to remind us of the centrality of time to human experience. Déjà vu excites an out-of-body experience: a potent and important reminder of where we’ve come from, who we were, and who we are now.

A 16th-century Greek fresco depicting the Old Testament dream story of

Jacob’s Ladder at the Dionysiou Monastery on Mount Athos.

It is the subject of one of the most delicate and affecting moments in literature. Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (1919) explains that a feeling of déjà vu is invariably linked not to any deliberated thought but rather to ‘physical sensations’, particularly tastes and smells: “the greater part of our memory exists outside us, in a dampish breeze, in the musty air of a bedroom or the smell of autumn’s first fires.”12 In the sequence, he dips a petite madeleine cake into a cup of lime-blossom tea and takes a sip. A sudden reminiscence makes him physically shiver with the ‘precious essence’ of a long forgotten memory, but agonisingly he cannot bring it back. In three pages of sublime writing he grapples to recall it and finally does, recounting the déjà vu place he once was, in a breathless torrent, like a seer:

…immediately the old grey house on the street, where her bedroom was, came like a stage set…and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square, where they sent me before lunch, the street where I went to do errands, the paths we took if the weather was fine…all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne, and the good people of the village and their dwellings and the church and all of Combray and its surroundings, all of this which is assuming form and substance, emerged, town and garden alike, from my cup of tea.13

Sense 2018

The rousing of Proust’s senses brings us neatly to 2018’s explorations. Sense is an enticing theme, since for many artists it is everything, and one so rich with possibilities in Singapore, where senses are in overload. Arriving at LASALLE, sensory exuberance greets the visitors everywhere they turn, from the visually spectacular campus with its Grand Canyon-shaped glass walls, to a pungently fragrant durian stall on the corner and the mouthwatering hawker food centres nearby.

Every year, the Lab is an intensely sensorial experience with an array of activities and stimuli, from gamelan jam sessions to boat trips around the islands and visits to colourful temples, markets, museums and galleries. For the Sense Lab, fieldtrips included the taste experiences of a sustainable vegetable farm, the smells of a perfume laboratory, and the visual splendour of the surreal 1930s Chinese mythology statue park, Haw Par Villa. It is my very favourite place of all in Singapore, and I have filmed its dioramas as part of my video Revisiting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, discussed later.

All Labs have in common the sensory stimuli of thought-provoking seminars, artist-led workshops, and the collaborative mounting of an exhibition. As is fitting in Singapore where food is king, the smells and tastes of communal meals remain a perennial highlight. They range from Japanese bento boxes and Hainanese, Indian, Malaysian and Peranakan lunches, to dinners hosted at the homes of artists and art lovers, and legendary barbeques with Milenko and his wife Delia at their fantastic art studio.

Photo by Steve Dixon

Haw Par Villa provided my inspiration to make a film interpretation of T. S. Eliot’s epic poem The Waste Land (1922). While

largely set in London, the poem frequently alludes to Asian cultures and religions, and the theme park’s dioramas offer perfect

backgrounds to a number of stanzas. Here, a statue of a fleeing woman in Haw Par, is juxtaposed with one of the poem’s

characters who is struggling with trauma, played by Kristina Pakhomova.

Erase 2019

This Lab was the 13th to be staged, a number many cultures consider unlucky, although others see it as highly auspicious. So it proved, with remarkable conviviality and collaboration, Erase was one of the most dynamic and interesting Lab exhibitions to date. It told captivating stories of erasure both personal and global. They included investigations of how society’s forgetting, omission and deletion of information impacts on understandings of truth, and the insidious emergence of a so-called post-truth. Erasure has never been more topical and vital than in our age of digital realities, and the artists’ takes on the subject shone penetrating light into these murky shadows. The exhibition was an enthralling mix of poetics, socio-political critiques, humorous offerings and some downright scary shit.

Famously, in 1953 a young, then-unknown Robert Rauschenberg turned up unannounced on the doorstep of a then-very-famous Willem de Kooning. He asked him to give him a drawing, explaining he would erase it. De Kooning kindly obliged, but since the sketch was in ink, crayon, pencil, and charcoal, it took Rauschenberg months and many erasers to rub it out. When he exhibited it with a few smudgy marks remaining, Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) caused an uproar, but has since taken a revered place in art history.

The joy of the piece rests, of course, in its anti-art provocation. The most ground-breaking works challenge, ask questions and make us reassess: “How an artist functions, and what the artist’s role is, the parameters of art, the nature of art. What is the bottom line? What is the least thing you need? What can you get rid of and still have a work of art? He initiated those things.”14

In Spite Of 2020

In the face of the 2020 pandemic and categories defining ‘essential’ and ‘non-essential’ workers, there was a spirited debate in Singapore’s newspapers on whether artists might constitute the ‘least-essential’ category of all. Artists argued their case in a noble and convincing counter-attack, but I was left reflecting on whether the whole ‘essential’ paradigm was suspect. We make art not because it is essential but because we are—we’re human, and want to express and connect with each other (which is essential). In times of crisis, art is what anchors us to our common humanity, reminds us that we’re not alone, and gives us hope. Nothing will stop us from making art.

The 2020 In Spite Of theme exemplified this stance, and provided a digital alternative to the usual physical art camp, with past participants coming together with LASALLE staff and alumni to share their creative responses to the pandemic. The online exhibition curated by Milenko includes my first artistic contribution to the Lab beyond inventing drinks: a video trailer for a film made with Singaporean composer Joyce Beetuan Koh interpreting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). It will be released in time to celebrate the poem’s centenary in 2022 and features a cameo by Milenko playing a murderous sailor who snarls like a dog.

Revisiting The Waste Land underlines its currency and potency for our own time. Eliot’s bleak yet beautiful meditations on isolation and alienation take on whole new meanings a hundred years after he penned them. He grapples with themes that echo uncannily with the anxieties surrounding the pandemic, from feelings of melancholy, loss and longing to the fear of death and the promise of renewal and rebirth.

For centuries, ‘In Spite of’ everything from plagues to world wars, artists have continued making art and, significantly, art has tended to make conceptual and aesthetic leaps in the wake of calamities. World War I (1914-1918) heralded the birth of the 20th-century avant-garde in Western art with Dadaism, Surrealism, Constructivism, Bauhaus and more. At seismic moments, artists are grounded in a brute reality while being fuelled by dreams of a better future, and united with others towards a common cause. Today, as a pandemic forces us physically apart, we witness artists everywhere activating their communities and forming ever stronger bonds.

Digestif

LASALLE is soon to be elevated to become part of Singapore’s first university of the arts, and as the College is less than 40 years old, it’s a remarkable story and achievement. The stellar rise has come about through hard work, high aspirations and a collective vision, first conceived by its formidable founder, the late Brother Joseph McNally (1923-2002). Like Tropical Lab, that grand vision is mixological, laboratorial and international: blending together dynamic faculty hailing from all four corners of the earth, promoting experimental art practices that fuse the most exciting ideas from global cultures, and collaborating enthusiastically with some of the world’s finest arts schools.

Photo by Steve Dixon

The Tropical King, Milenko Prvački, acting in another role—as the psychotic sailor,

Stetson, in Revisiting T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land.

Today, the College has many high-profile international projects and collaborations, but Tropical Lab was the first, the most pioneering and the longest lasting. It helped establish LASALLE and put it firmly on the international map; without it I very much doubt we would have become a University quite this soon. Long may it continue.

Viva Milenko! Viva LASALLE! Viva Cocktail Lab!

Cheers