If you see someone without a smile, give them one of yours…

The tagline of countless motivational posters or staffroom mugs; words perhaps repeated before pulling on the Mickey Mouse hat for a day’s work at Disneyland. Despite the queasy overtones, the phrase sticks in my mind as the innocent, authentic exhortation of my father. My father—the inveterate hugger, scooper-up of lost souls, listener, counsellor, feeder, dragger of people on long walks.

My barometric measure of hospitality is calibrated to the weather my father created—the noisy, rambunctious melee into which solitary individuals would be ushered, another chair entering the ring of light, forcing the circle of seats ever further back from the dining table. My mother would eke out the meal and another blinking participant would be made warm in the glow of this generosity. Family legend also describes the way my sister once hissed to my mother that “Daddy has invited back the whole orchestra.” This type of largesse so lavishly unleashed is mostly perceived as a forcefield of good intent, a warming welcome, a show of acceptance of those beyond our ken, our kin—a flattening of difference. It is societally valorised to be seen as a ‘good host’ and rare to find a dissenting viewpoint. We have likely all at some time been the subjects of good hosts, felt the hand on our shoulder indicating acceptance, tasted the symbolic water or tea or wine, or broken the bread that signifies reception. We might well have been provided with a bed for the night, and offered company and safety in an unknown land.

The halo of nostalgia accompanying my childhood recollections diminishes with an investigative trawl through personal experiences of being a guest. Viewed both empathetically and retrospectively, the dazzled muteness of those on the receiving end of the ‘guesthood’ bestowed by my father may actually reveal annoyance or an acute discomfort of personal boundaries overstepped or individuality ignored. This threshold of hospitality, of bodies and places and perspectives, is a shifting and mutable territory, and as I revisit similar scenes, I recognise how nuanced and fickle these experiences are, how internally and subjectively such a public exchange is perceived, and how inadequate any universal notion of hospitality was.1

Perhaps we ourselves have inhabited that role of the cherished guest, whose gratitude is warmly anticipated by an attentive host, and we have felt that debt of appreciative gestures, correspondence, and gifts? The weight of this expectation colours and alters the guest’s behaviour as they strive to adhere to the cultural, performative and aesthetic expectations germane to ‘guesthood’. The labour to maintain the pliancy and bonhomie of this state can be overwhelming and exhausting on both sides, either to scurry to offer relaxation, or to visibly demonstrate the accepted levels of relaxation and to sensibly decode the degrees to which the offer to ‘make yourself at home’ really pertain.

Despite his own enthusiastic sense of hospitality, another one of my father’s maxims, “Fish, friends and family go off after three days,” is echoed by Lorenzo Fusi in the text which accompanied the 7th Liverpool Biennale.2 He describes the temporal problem implicit with many forms of hospitality: the implicit agreement that the guest will, for a short time, excitingly disrupt the equilibrium of the host’s domain, and then leave in a timely (three-day) fashion.3 This time limit would seem to me to be generous to both host and guest, providing a structure around which the rituals and spaces of hospitality can unfold, and the implicit message that the adrenaline required to inhabit this shared liminal space is finite.

So, what about that other guest? The guest who will not conform to unspoken rules, the one who will not leave, who seems not to notice your stifled yawns or the rumbling undercurrent of friction broiling in their wake. We can probably all remember guests such as these, whose innocent gestures, humour or even their apparel can seem designed, over time, specifically to madden and infuriate. The question “How long can you stay?” is charmingly uttered with a strained lilt at the end of the sentence and eyebrows smilingly raised in false accommodation. Overreaching hopes of hospitality and entitled expectancy create a chasm of misaligned intention, which the lingering guest ushers in and illustrates to an almost ecstatic degree of tension. The equal and opposing forces of guest and host each illuminate the other, and the equilibrium presupposed in the paradigmatic model of guest and host shifts dynamically whenever one party shifts to and fro along the spectrum— either failing to meet or exceeding the tacitly pre-agreed expectations existing in either party’s head. What it is, to be a guest or a host, and all the vagaries between the possible polarities of these positions will form the multiple perspectives of this piece.

I wanted to draw upon my own experience as an artist to reflect upon hospitality—both given and received—and to then use this example to unfold the metaphor of hospitality into a consideration of the political, social and environmental tropes of hosting and ‘guesthood’. I will be using the model of Tropical Lab as a lens through which to unpick artistic notions of ‘guesthood’, hospitality, and temporary community and to reflect upon the delicate and authentic welcome offered through the structure of the Tropical Lab international artistic residency, established by its host, Milenko Prvački. Tropical Lab is a residency programme which offers an atelier or hosting space within which artists from around the world can create, collaborate and share praxis, a literal laboratory for experimentation, an “annual international art camp for graduate art students” which I attended in 2015. The two-week period for which we artists were invited to make home at LASALLE College of the Arts overstepped the three-day temporal boundary in a manner exercised by countless artists embarking on international residencies. We brought, and were encouraged to bring with us, any tool literally or metaphorically required, our research and practice methodologies, a propensity for porosity, collaboration and participation, as well as a readiness to produce artistic outcomes emerging from this experimental period. The hidden ‘baggage’ that undoubtedly trailed us around baggage reclaim and the arrival lounge was a certain sense of entitlement and privilege—that we were invited.

Creating work during Tropical Lab with help from Marko Stankovic, University of

Belgrade, and Victoria Tan from LASALLE College of the Arts. Photo courtesy of

Kay Mei Ling Beadman, City University Hong Kong, 2015

Singapore struck me, during my time there, as a demonstrably cordial location, vivid with the industrialisation of hospitality, bestowing international largesse as a form of statecraft. From my arrival in Singapore’s luxurious Changi Airport, I was then smoothly whisked to the hostel which would house us for our stay. We were welcomed by student ambassadors who soothed our technological anxieties and led us to SIM card purveyors, then fed, watered, welcomed, entertained, sheltered. We were assured, through the internationally industrialised hospitality structures, of our guest status, and our roles as hosted participants was refined through the institutional introductory activities held at LASALLE. Beyond these formalised modes of exchange, however, we were enveloped in the warmth of Milenko Prvački’s, the ambassadors’, LASALLE’s and the wider city’s welcome. I was unaware at that time of the Singapore Kindness Movement, launched by the Singaporean Tourism Authority, which I first encountered in Irina Aristarkhova’s book Arrested Welcome.4 She describes similarly the overwhelming experience of arriving at the airport which, with its orchids, butterfly gardens and swimming pools, seems to be determinedly aiming for the very pinnacle of international air hospitality. She describes the city’s state-sponsorship of the tourism sector through the Economic Development Board and its goal of becoming the most welcoming international travel hub. She describes too how as a white woman she “benefitted from the racist and imperialist legacies of Singapore’s colonial history as part of the British Commonwealth, as well as from its postcolonial and authoritarian present, when tensions and inequalities around race were being managed by the government from the top down.”5

When I first arrived in Singapore, in July 2015, it was approaching the 50th anniversary of the city-state’s founding and there were abundant celebration plans afoot. My practice research is usually rooted in a geological, archaeological, historical enquiry and as such, during Tropical Lab I decided to build on previous research into the triangular trade routes of the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th Century. I was intrigued by the implicit role of the East India Company in this trade and their entanglement, through the import and export of cotton and other goods from India, via trading ports such as Singapore, to destinations such as Liverpool and Bristol, where they would then continue their journey to West Africa to be commodities traded in exchange for slaves. Plantations in the Caribbean were then worked by these slaves until the Abolitionist and Slave Uprising movements, whereupon indentured workers or coolies would then be brought in from India and China. Singapore was ‘settled’ by the piratical Sir Stamford Raffles on behalf of the East India Company, himself born on a boat off Jamaica, and it seemed to me that the ghostly traces of these trade routes clearly lingered, echoed in the business and busyness of Singapore’s international flight trajectories and shipping channels.

While in Singapore, I became acutely aware of the lack of visible history, but also the heritage traces which had been maintained, and preserved. Patrick Wright describes poignantly the view that “heritage is the backward glance taken from the edge of a vividly imagined abyss,”6 and it seemed to me that Singapore had inverted this western obsession with heritage and had, in the abyss, found its modus operandi. My fellow Tropical Lab alumnus, Singaporean Patrick Ong, spoke of how the number of storeys of each building had exponentially grown during his lifetime, each decade doubling, from four to eight to 16 and so on. The lack of nostalgia, my coming from a Britain that is both romanced by and myopically unaware of its own past, was refreshing, yet oddly haunting, as I hunted for any patina that might indicate past lives. At the same time, the throwback vison of the last-remaining kampong (traditional village) on the island Pulau Ubin, a “window into Singapore’s past,”7 and Raffles Hotel Singapore, “a heritage icon, whose storied elegance, compelling history and colourful guest list continues to draw travellers from around the world,”8 provided a fascia almost more sanitised than the version of Singapore that Resorts World™ Sentosa offers.

It appeared that in the same way that capable hosts provide the most sterile, edited and curated version of their homes for guests to appreciate, so too Singapore was tidying up and repackaging any messy or inconvenient histories into tourism packages.

A bewildering array of over 40 Passion tours are available through the official Visit Singapore website—focusing on food, action, socialising and ‘culture’. This catch-all term offers insights to the lives, among many, of those in Singapore’s Malay and Jewish communities, Chinatown, the Chinese cemetery, Little India, and more. If I were to undertake the Unity in Diversity tour, I would “get a better understanding of the racial mix in Singapore as you learn the different lifestyles and practices of these communities.”9 This well-meaning sentiment tries hard to offer a glimpse into the complexity of Singapore’s cultural and racial make-up, how these communities co-exist and feed into the global outlook of the nation state. The patchy reality I encountered in the run-up to the 50th anniversary celebrations was disorienting, vibrant and exciting, but troublingly asymmetric in the distribution of wealth. As a casual observer, the inequities woven into the East India Company’s historic ruling structure remained as visible stitches within the patchwork of the city.

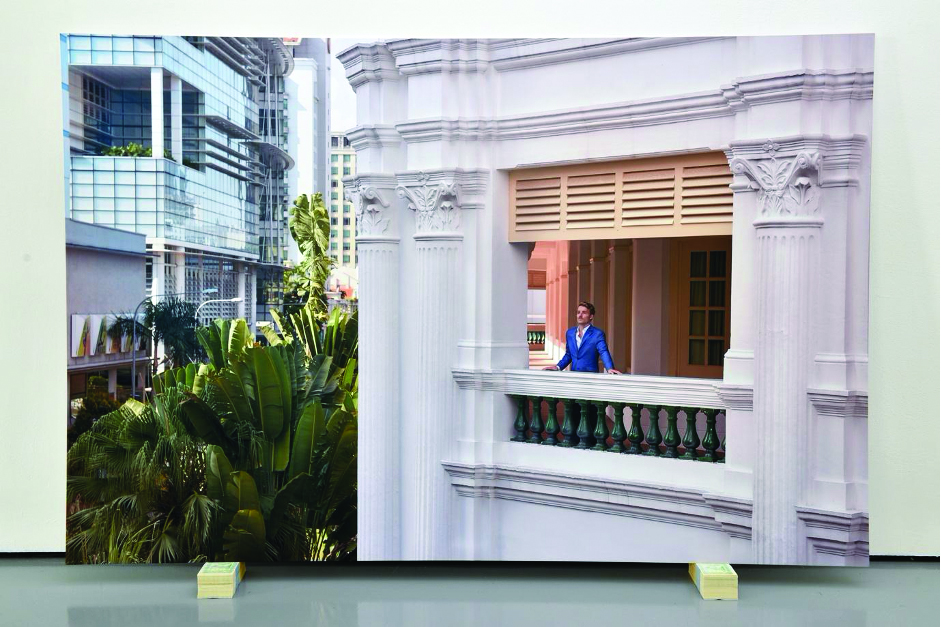

Feeling Raffled. 2015. By Andy Kassier, digital photograph on Dibond, 115 x 175 cm

Photo: LASALLE College of the Arts

As part of the Tropical Lab residency, I decided to make a sculptural ‘map’ of this multi-scalar, multi-temporal and multi-spatial web, perhaps a chaotic visualisation redolent of Benjamin Bratton’s theory of “the Stack,”10 a multidimensional computational model described by cultural theorist Jacob Lund as “the development of planetary-scale computation…which interconnects a number of different layers and facilitates interpenetration between digital and analogue times, and between computational, material and human times—bringing into being a kind of planetary instantaneity in which everyone and everything takes part.”11 Planetary scale computation would seem to be the material or immaterial equivalent to the East India Company’s trading goods, be they human, mineral or vegetable, and an equivalent too to the globalised transportation of goods as witnessed in Allan Sekula’s Fish Story, To be Continued which I was able to encounter at NTU CCA (Nanyang Technological University Centre for Contemporary Art) in Singapore during the residency.12

Allan Sekula, The Forgotten Space (2010). Installation view in Allan

Sekula: Fish Story, To Be Continued, 3 July–27 September 2015.

Photo: LASALLE College of the Arts

The use of an industrial material redolent of a colonial past such as rubber, with its global history of imperial theft and colonisation of the landscape, seemed an apt vessel to carry these traces of cargo routes, inscribed with ongoing human loss. To source the rubber required—an inch-thick metre square slab, the tools and sacking material to print on—I repeatedly trawled the streets of Little India’s industrial vendors, a tall pale woman walking the humid streets in the midday sun, visibly adrift in this scene. Despite my solitary roaming and dishabituation in an urban environment, I always felt safe. This is afforded, in part, by Singapore’s famous civic ‘safeness’, of which it is justly proud, a companion to its legendary cleanliness and stringent legislation concerning the disposal of chewing gum. These urban ‘myths’ come to be true for many guests to the city-state, through their repeated tellings and experiences, but just as my children are exhorted to be on their best behaviour when guests arrive, this impression may extend only to certain groups or circumstances. During my long walks around the less pretty areas of Singapore, I knew that while the security, curiosity and hospitality I was experiencing was an incarnation of what I came to know as the Singapore Kindness Movement, I felt, too, a certain privileged entitlement to safety because of who I, as a white woman, was.

I remember as a callow youth spending a year teaching English (rather badly) on an island off the northern coast of the Central American country, Honduras. Ranked as a country with one of the highest murder rates per capita in the world, during that year, I vacillated between being bizarrely nonplussed by the ubiquity of firearms and being horrified by the associated fatalities and injuries among the community of which I had become a part. Throughout that year, despite the incredibly close shaves I encountered and survived, I felt myself insulated from real harm because of a (probably) misplaced confidence in my own importance. Surely these local ‘rules’ and dangers did not apply to me? Was this the safety promised by the offer of hospitality, or was it my privileged position as a white person, with the scrutiny of the charitable organisation I volunteered with and a powerful national embassy which scaffolded the precarity of my stay? The unevenness of this recollection brings into focus the key differences in expectation between being a guest and being a neighbour. Despite the year-long duration of my stay in Honduras, far in excess of three days, on reflection, I never truly troubled the definition of neighbour, despite superficially fulfilling Aristarkhova’s definition, that neighbours are demarcated by “their proximity in space (living near to one another) and time (being together in the same moment).”13 The temporary condition of my time there was always a given, there was always an end point in sight, akin to that moment of exhalation for a host when a guest leaves, the instance when the guest can resume his or her own routine and ritual. This mutability of time and space, between ‘guesthood’ and neighbourliness, resonates strongly with my experience of Honduras, and my impressions of Singapore. I strongly recall the lines of guestworkers queuing to return to their home countries as I departed Changi Airport at the end of my stay, this international limbo being something many of us have witnessed at other travel hubs around the world.

‘Guest’ is a term that can hide subtle violences: it can connote the idea of being detained, in the UK, ‘at her Majesty’s pleasure’ in a prison institute. The term that the gastarbeiter regime is a low cost means of increasing flexibility in cases of regional and/or sectoral bottlenecks in the employment system as well as a way of ‘exporting’ problems…”’]gastarbeiter,14 which I came across as a German-learning teenager, also withholds the welcome that hospitality might be expected to convey. The term, meaning guest worker, emerged under a policy, which was developed in the 1950s following a series of treaties between Germany and other countries in which migrant workers to Germany were invited with the implicit expectation that when the required work was done, the guest workers would return to their homelands. The imaginative failure lay in Germany’s inability to anticipate that the temporary nature of the invitation was not made explicit. Germany’s Federal Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble said: “We made a mistake in the early 60s when we decided to look for workers, not qualified workers but cheap workers from abroad. Some people of Turkish origin had lived in Germany for decades and did not speak German.”15 The uneasy accommodation arrived at in this scenario of free(-ish) movement speaks of a failure of hospitality, or what Aristarkhova terms an ‘arrested welcome’. The state, in this case Germany, ‘generously’ offers hospitality, on their own terms, to their benefit, in the process making the assumption (probably drawn from their own privileged experience of being hosted) that it will naturally come to an end. The offer turns out to be hollower than expected—the terms perhaps unclear, or perhaps the opportunities available become too great to ignore and the stereotyping, the lumping together of inanimate groups of ‘others’ who ‘take advantage’, incrementally mutates into state-sponsored communal inhospitality.16 The grey area or threshold between hosts’ and guests’ expectations once again comes into question as does the scenario outlined by Lorenzo Fusi, as he states: “As for the household, so for the nation state.” He goes on to describe the conundrum for the civil state: “How can we articulate, politically, and demonstrate the notion of hospitality to those seeking shelter if hospitality is supposed to be temporary?”17

This state-sanctioned fear of the ‘other’ rejects Derrida’s notions of “unconditional hospitality” (described in Greek as Oikonomia) and interrogates the etymological roots of the words host and hospitality. The terms home and hospitality signal a shared commonality within a space and an implied generosity to outsiders, but we tend to, in the words of Derrida, attempt a difficult distinction between:

the other and the stranger; and we would need to venture into what is both the implication and the consequence of this double bind, this impossibility as condition of possibility, namely, the troubling analogy in their common origin between hostis as host and hostis as enemy, between hospitality and hostility.18

The derivation of the Latin root word hospes, can be translated severally as either host, guest, or stranger, even enemy, meaning that the act of hospitality often remains simultaneously alert to the foreign, the dis- or mis-placed. Just as invasive species such as buddleia is the first pioneer plants to colonise the ruins, it is sometimes depicted in the right-wing media as ‘invasive’, with ‘flooding’ tendencies that may begin to make a home in the ruins. Homes can be welcoming (heimlich) but can also signify exclusion that their owners may exert: a controlling and undermining hospitality, creating boundaries between who belongs or who doesn’t (Sigmund Freud’s The Uncanny or Unheimlich).19 As with hospes, heimlich and its antonym unheimlich also share a fugitive meaning, which slips between polarised positions.20 Homeliness resonates strongly with themes of oikos, the Greek term denoting family, property, home. This basic unit of Greek society, the root of the terms eco-nomy and eco-logy which have always been the twin catalysts of social human life on Earth, is now sharply whittled into competition as protagonists within the theatre of the Anthropocene, performing an embattled version of living in the ruins. This is endorsed in the writings of Achille Mbembe:

In most of the major urban centres faced with land problems, distinctions between “indigenes,” “sons of the soil,” and “outsiders” have become commonplace. This proliferation of internal borders—whether imaginary, symbolic, or a cover for economic or power struggles—and its corollary, the exacerbation of identification with particular localities, give rise to exclusionary practices, “identity closure,” and persecution, which, as seen, can easily lead to pogroms, even genocide.21

We are witnessing a global convulsion of a ‘new’ form of racism,22 distinct perhaps from the ‘traditional’ forms invoked through colonisation and the transportations of humans through plantation-based slavery, engendered by nationalistic kneejerk reactions towards economic or refugee-induced migration. The widespread sentiments towards the ‘Other’ to “go home,” completely ignorant of the histories of settlement or community-building, are vividly active around the world and feed into the distancing narratives between ‘us’ and ‘them’. The negatively associated language used in such instances, such as alien or asylum, reinforce any perceived difference, and if guests can be said to hold up a mirror to the hosts’ own selves, what monster is it that is reflected? As David Scott points out in a conversation with Stuart Hall:

The idea of hospitality (thus) puts in discursive play a number of cognate concepts, among them tolerance, generosity, diversity, that are central to the contemporary self-image of the liberal democratic state. The foreigner, holding up a mirror to the host, enables or provokes a deepening transformation of the self of the host.23

This externalised viewpoint was one that I held during my stay in Singapore and is reflected in the way that the city-state seriously considers the image that it wants to convey. The Passion Tour which celebrates Singapore’s cultural diversity is a slight contortion to eliminate any negative accusations of ghettoisation within the city between ethnic groups, instead converting it into a positive affirmation of porosity and cosmopolitanism (after Kwame Anthony Appiah).24 Fusi states that: “By being positioned outside the rule (the house/the state etc.), the guest is not excluded by or from that rule as such, but rather defines it…while remaining outside its internal logic.”25 Inhabiting that wide threshold that hospitality creates, operating within a rule system while aware of its machinations and its temporary minimal hold, is a luxury that is unavailable to many; in the words of Aristarkhova, to the “uninvited,” the “existentially unwelcomed,” it is a “hospitality withheld.” The Covid-19 pandemic has introduced a further layer of fear of the Other, a mistrust of proximity which goes beyond what Aristarkhova has considered when she describes her involuntary facial distortion after a man joins her in a Moscow lift and his subsequent response:

“Are you afraid of me?”

I replied honestly, “Yes.”

No other word was exchanged between us.26

She goes on to interrogate her internal assessment of her own sense of safety and to pick apart whether or not he had a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ face. When we are all masked, our intimation of danger seems that much higher. I recently re-entered the university library for the first time, during the Covid-19 era, to collect some titles that I was unable to access online. The library was quiet and empty, late on a dark afternoon. I waited for the lift and jumped back in fright as the door opened, seeing a young woman in there. We had an awkward conversation about the etiquette of lift sharing, if she minded that I joined her, and so began our journey in tense and slightly embarrassed silence. My fraught response to such an innocent presence later made me laugh at my response, and to evaluate how I judged her to be ‘safe’. I clearly followed the set neural pathways that instantly judged her to be no risk, but how would it feel to be always deemed a risk, to be Other, foreign, uninvited?

This year, a time of pandemic, of global human rights demonstrations and of Black Lives Matter protests, has shone a harsh light on the ‘existential unwelcome’ so many people experience on a daily basis. Hospitality and its conventions and gestures are not meaningless, and institutions and states are still made up of humans who can be humane.

To paraphrase Fusi, the question is whether we are politically and psychologically able to behave as neighbours, rather than act as hosts,27 and if hosts, hosts who do not make a demand of gratitude. The moral imperative is made plain when Aristarkhova quotes Dina Nayeri, the author of the novel Refuge and a former refugee herself:

It is the obligation of every person born in a safer room to open the door when someone in danger knocks. It is your duty to answer us, even if we don’t give you sugary success stories. Even if we remain a bunch of ordinary Iranians, sometimes bitter or confused. Even if the country gets overcrowded and you have to give up your luxuries, and we set up ugly little lives around the corner, marring your view. If we need a lot of help and local service, if your taxes rise and your street begins to look and feel strange and everything smells like turmeric and tamarind paste, and your favourite shop is replaced by a halal butcher, your schoolyard chatter becoming ching-chongese and phlegmy ‘kh’s and ‘gh’s, and even if, after all that, we don’t spend the rest of our days in grateful ecstasy, atoning for our need.28

Echoing Nicholas Mirzoeff’s Right to Look,29 Fusi reiterates that the “right ‘to be’ cannot be mistaken for an act of generosity.”30 This surely has to be the take-home message from any model of hospitality: you can offer ‘service with a smile,’ and if you see someone without a smile, give them one of yours, but really, if you must give, give without expectation of gratitude, and give space for equality, for a ‘right to be.’ Smiling in this way can, after all, be a political act.31

“Singapore ‘smiley-face’ activist in one-man protest.”

Photo courtesy of Jolovan Wham/Instagram, 2020