Since 2005, art students from universities in Bandung, Belgrade, New York, Plymouth, Tokyo, and so on, meet each other at LASALLE, to work and live together in Singapore as part of Tropical Lab. An experiment in art education, this two-week intensive art camp was initiated by artist Milenko Prvački. In its establishment, Tropical Lab was informed by the artist’s youth experience with art colonies in Tito’s time, art camps functioned as a refuge from political control. They were isolated, mostly in nature, historical locations or monasteries. Artists from Yugoslavia and international artists will be in residence for one to two weeks and communicate, debate, exchange, experience. I did visit many of them in Počitelj, Mileševo, Ečka, Bečej. I was running Deliblatski Pesak.” Milenko Prvački in conversation with the author, September 2021. ‘]former Yugoslavia.1 Such retreats that Prvački witnessed in his youth share similarities with current artists-in-residence programmes across different geographies. Irrespective of their different models and resources, these initiatives, including Tropical Lab, are driven by common beliefs. Exceptional conditions as in dedicated time, space, and new exchanges with people and places, can play a transformative and long-lasting role in an artist’s practice and fulfil a clear function in an art system. Within the histories of art colonies and artists-in-residence programmes, it is not surprising that Tropical Lab is the result of an artist’s vision. Artists have often taken a leading role in creating conditions for their peers to produce and display art and generate discourse. This understanding that an artist beyond one’s art-making can or should operate at interconnected levels of an art ecology fuelled many of such artists’ initiatives.

In a questionnaire, several artists shared that Tropical Lab made them step out of their comfort zones and broadened their perspectives.2 I can testify to a similar experience curating this survey exhibition of a selection of former participants in the Tropical Lab. When I was invited to embark on this mission, I immediately agreed. I knew that in the nature of a programme such as Tropical Lab that is grounded on exchange, unexpected encounters and connectivities will arise in the process of exhibition-making: encounters that the current pandemic Covid-19 made rare and precious. I was introduced to a diverse group of 25 artists active in the field and selected by Tropical Lab faculty partners.3 While this framework combined with different Covid-19 provisions in the gallery spaces (no use of headphones, for instance) might feel restrictive, it compelled me to return to the basics of exhibition-making. I had to think carefully about the triangulation between space, artwork, and visitors, patterns of access and mobility, material textures, conditions of lighting, all elements that combined together, give an aesthetic form to an exhibition. I was preoccupied with creating the right setting for each work and optimising its relation with the respective location—whether of fusion or contrast. Most importantly, the diversity of existing and new artworks in this exhibition from large-scale paintings, immersive animation, post-minimalist sculpture, wall drawing, interactive augmented reality and so on, not only paid justice to the wide breadth of contemporary art but made me consider diligently the needs of each artwork and the specific experience it entails.

As an exhibition that celebrated 15 editions of Tropical Lab and preceded the launch of a digital archive and ISSUE’s special volume, it asked, I believe, for a moment to ponder on the nature and value of such an artistic exchange. As such, the proposed title Interdependencies was less thematic and more reflective. It captured the spirit of togetherness, peer learning, and cross-pollination that defined all the previous editions of Tropical Lab. In times of antagonistic discussions around identity, it is worth returning to Edward Said’s understanding of culture as a matter of “interdependencies of all kinds among different cultures.”4 Said rejected the assumption of such things as original ideas and indirectly of what has often been coined in relation to non-Western worlds as derivative works. He saw cultures as always permeable, “the result of appropriations and borrowings, common experiences,” a process that has also served expressions of resistance and opposition to dominant structures.

In addition, the notion of ‘interdependencies’ spoke to the current moment. While the pandemic touched our existence in many different ways and hindered off-screen encounters, it made us all acknowledge our interdependencies as fundamental to art and life. There was no expectation in the selection of the artworks or the development of new projects to directly address the pandemic. And it is precisely the absence of a prescriptive approach that made it possible to observe how in manifold ways the pandemic did influence and permeate artistic production creating overall in the exhibition a sense of a collective experience in tune with the planetary unfolding of current events.

Lastly, the concept of interdependencies played an important role in the layout of the exhibition determining juxtapositions and associations between artistic positions and contexts of reference, as well as endowing each gallery space with a distinct mood. Of course, one might argue this is always the case of any group exhibition, in particular those of a larger size. Yet, when artists are brought together for no other reason or agenda than the quality of their practice as was the case of this exhibition, the differences between artworks tend to be less flattened and the usual search for a common denominator becomes of secondary importance. Each artwork occupies a specific position and can serve as a point of departure for a broader discussion.

As curatorial essays or catalogues often precede the completion of the show, exhibition histories tend to be short of accurate documentation. Led by this consciousness and favored by a leeway of time following the installation of the show, I transposed into a spatial transcript for interested readers, a tour of this exhibition as experienced on site by various groups of visitors.

McNally Campus

A key aspect of this exhibition was to highlight the special relationship the artists taking part in the Tropical Lab have had with LASALLE’s McNally campus, which was an integral part of their exchange, learning and artistic production. As such the exhibition stretched in situ across the campus, outside the three galleries: Praxis Space, Project Space, and Brother Joseph McNally. This proposed approach became more convincing during the conversations I conducted with several artists when I was pleasantly surprised that their memories of the campus felt so fresh and vivid even years after their trip to Singapore. In the spirit of interdependence, artworks were integrated within the campus—co-existing with students’ activities and making use of the current infrastructure, such as existing screens.

Inside the College’s Ngee Ann Kongsi Library, one of the two screens (LED TV monitors) that faces the glass entrance, played James Yakimicki’s animated painting; this generated a spontaneous moment of encounter between artwork and passing students (Fig. 1). The cascading effect of the river that cuts through a landscape informed by the artist’s visit to Singapore was amplified by the verticality of the screen. Liu Di’s sleek and speculative digital video was hosted on a 3M screen at the Creative Cube: a multidisciplinary performance space, catching the attention of both students and the general public because of its location facing a public passageway. Imbued with a futuristic imagery, fashion and choreography, the video animated the campus and spoke to the inherent interdisciplinarity and cross-pollinations in an arts college such as LASALLE (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1

James Yakimicki, 2012–RISING FALL … 2021–CHEWED UP & SPIT OUT(NOTHING MATTERS), 2012/2021,

oil on stretched linen animation by motion leap, 152.4 x 200.66 cm

Fig.2

Liu Di, Pattern, 2020, high-definition digital video, cinema 4D software, 2:00 mins

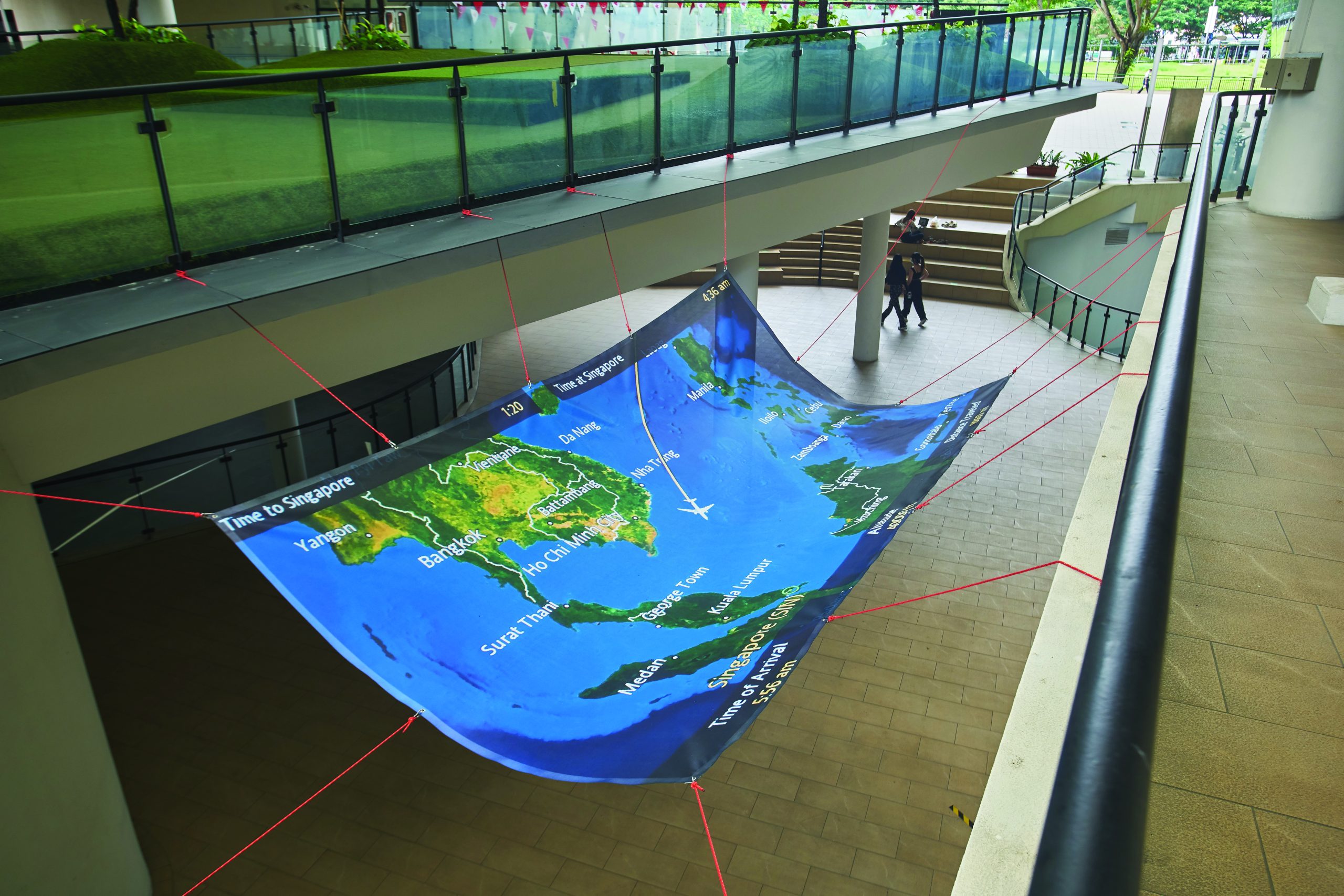

From various points in the campus, one would notice a large piece of tarp levitating above the ground, intermittently shaken by gusts of wind, or beginning to buckle under the force of the rain (Fig. 3). This shelter-like structure was hung outdoors in close proximity of the campus amphitheatre stairs where students often socialise, gather for lunch and meetings. The screengrab printed on the tarp was taken by the artist Duy Hoàng on his trip to Singapore in 2017 at a point when the plane was crossing nearby Nha Trang, the artist’s hometown. This was the closest the artist has been home in the past two decades which made this personal experience, as suggested by the artwork title Perigee, match the intensity and singularity of a celestial event. The suspended tarp conveyed the elusive experience of belonging for those uprooted from “home.”

Snippets of conversation punctuated with visceral and onomatopoeic sounds permeated the immediate surrounding area and became more palpable outside the entrance of Brother Joseph McNally Gallery (Fig. 4). Here the two-channel sound installation by Brooke Stamp in collaboration with performer Brian Fuata was literally suspended in mid-air. The attempt to create a psychic communion in times of isolation and distance took the form of a parallel relay communication between the two artists improvising from their respective locations. The sound flew up, shifting the visitors’ gaze towards the distinctive campus sky bridge. While the bridge served as a metaphor for this experiment, the nonsensical dialogue acknowledged the difficulties, if not the impossibility of communication in these exceptional times. A sound installation of a different nature, this time linear and cohesive, was hosted in an open-access space. In this quiet and secluded space, beside Creative Cube foyer, visitors could eavesdrop on the conversation between the artist B. Neimeth and her 95-year-old grandmother. Their different, often conflicting views on dating life and gender dynamics marked a generation gap that, nevertheless, was softened by the affectional bond between the two women (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3

Duy Hoàng, Perigee, 2021, print on tarpaulin, ropes, 280 x 448 cm

Fig.4

Brooke Stamp in collaboration with Brian Fuata, Psychic Bridge, 2021,

two-channel sound installation, 64:00 mins

Fig.5

B. Neimeth, My little old shrimp woman dried up like a prune, 2021,

two-channel sound installation, 23:55 mins; Erika from the Archive 4, 1946/2018,

archival pigment print photograph, 15.24 x 10.79 cm

Praxis Space

From all three galleries, Praxis Space exuded a contemplative and poetic mood with a constellation of artworks providing a meditation on life, disappearance, and acts of remembrance. Visitors who entered the gallery could step on vinyl showcasing cracks onto the floor (Fig. 6). The work was based on a performance in which the artist Pheng Guan Lee rolled a 700 kg sand and wax ball across a tiled floor that broke during the process. Manipulating the documentation of this past performance into something anew, the artist highlighted that irrespective of technological accuracy and capacity, our memories are malleable and adjustable to fit desired narratives. At the opposite end of the entrance, Homa Shojaie’s video proposed another form of reconstruction (Fig. 7). In an epic effort, the artist presented nine different phases of the moon, by editing frame by frame twenty-five seconds of an original video that captured the reflection of the full moon in a pool of water. A Turkish and a Cantonese pop song with a haunting melody, sounds of barking dogs and rippling water accentuated the nocturnal and sentimental tone of this devotional piece to the moon.

Fig.6

Pheng Guan Lee, The Spin, 2021, digital print, 420 x 170 cm

Fig.7

Homa Shojaie, still from [15931 moons] (Mehr o Mah / Sun and Moon), 2021,

digital video, 4:55 mins. Courtesy the artist

Tim Bailey’s painting on aluminium was in equal manner the result of memories and chance. Informed by the Japanese Zen temple gardens, in particular, Kyoto’s 15 stones sand garden (Ryōan-ji), and shaped by the interaction of materials between the non-absorbent coating aluminium and paint, this work was a reminder that the unknown is an integral part of life. In its close proximity, Ben Dunn’s deceptively simple painting offered a space of observance, an intimate memorial produced in the midst of the pandemic in the United States. Made of wood from diseased trees from forests, the painting’s lower curved shape held a dry pigment as an offering to materials that make art possible. High up on the wall, Rattana Salee’s brass sculpture is a replica of one of the few remaining columns of the abandoned Windsor Palace in Bangkok. Its destruction speaks of the inevitability of disappearance (Fig. 8).

The long wall of Praxis Space faces the outside, benefiting from natural light and subjecting the works on display to daylight fluctuations. Shuo Yin’s diptych produced a confrontational encounter with the viewer (Fig. 9). Blowing up small ID photos over 100 times, the artist conveys the process of othering that many immigrants experience. Through lack of details, the faces become blurred signalling the loss of personhood when one’s existence is continuously reduced to simple identity markers, such as nationality or ethnicity.

Fig.8

From LEFT to RIGHT

Homa Shojaie, [15931 moons] (Mehr o Mah / Sun and Moon), 2021, digital video;

Tim Bailey, Yellah (stones), 2021, oil and varnish on coated aluminium, 150 x 100 cm;

Ben Dunn, Untitled, 2020, wood and pigment, 51 x 42.4 x 3.9 cm;

Rattana Salee, Old Column, 2017, brass, 36 x 36 x 46 cm

Fig.9

Shuo Yin, WA and CA, 2020, oil on canvas, 231 x 259 cm

Fig.10

From LEFT to RIGHT

James Jack, Ghosts of Khayalan, 2021, natural pigments, wax on wall, dimensions variable;

Ali Van, The Mandarins, 2020–21, glass, old fruit, blood, breath, moon, 2010-x, dimensions variable

Created in situ, James Jack’s drawing on the wall was a visual diagram of the artist’s long-term research on Khayalan Island understood as a realm of imagination (Fig. 10). Taking the shape of a fishing net, the drawing generated kinships and preserved memories between people, places, stories, objects convened in this research. An integral part of this entanglement were the drawing’s colours produced out of local pigments from different parts of Singapore: Pulau Hantu (Keppel), Queenstown, Redhill and Jalan Bahar, respectively. Keeping this wall drawing company, on a low standing platform that allowed for closer inspection, Ali Van’s mesmerising and fragile glass orbs containing different organic materials lay: withered flowers, dry mandarins, ashes, menstrual fluid (Fig. 11). Each orb is a capsule of time, the artist’s idiosyncratic diary.

Fig.11

Ali Van, The Mandarins, 2010-x, glass, old fruit, blood, breath, moon, dimensions variable

Brother Joseph McNally Gallery

A constellation of artworks that tested the possibilities of sculpture or responded to climate crisis and colonial histories defined this gallery. Sarah Walker’s video directly faced the visitors entering Brother Joseph McNally Gallery (Fig.12). The visitors became, as with the subjects in her film, witnesses to something unknown—a disaster perhaps that faded slowly into the background.

Fig.12

From LEFT to RIGHT

Waret Khunacharoensap, Who is Sacrificing? 2021, print on canvas, 60 x 100 cm;

Tromarama, Stranger, 2021, 3D printed resin and artwork from LASALLE College of the Arts Collection, Institute of

Contemporary Arts Singapore, unknown artist and unknown production year, both 70.5 x 15.5 x 15.5 cm;

Anne-Laure Franchette, Travaux Temporaires (Temporary Works), 2021, plywood and paint, 104 x 58.5 x 170 cm;

Sarah Walker, Ado (Pillar of Salt), 2019, high-definition digital video, 15:00 mins

Fig.13

Tromarama, Stranger, 3D printed resin 70.5 x 15.5 x 15.5 cm

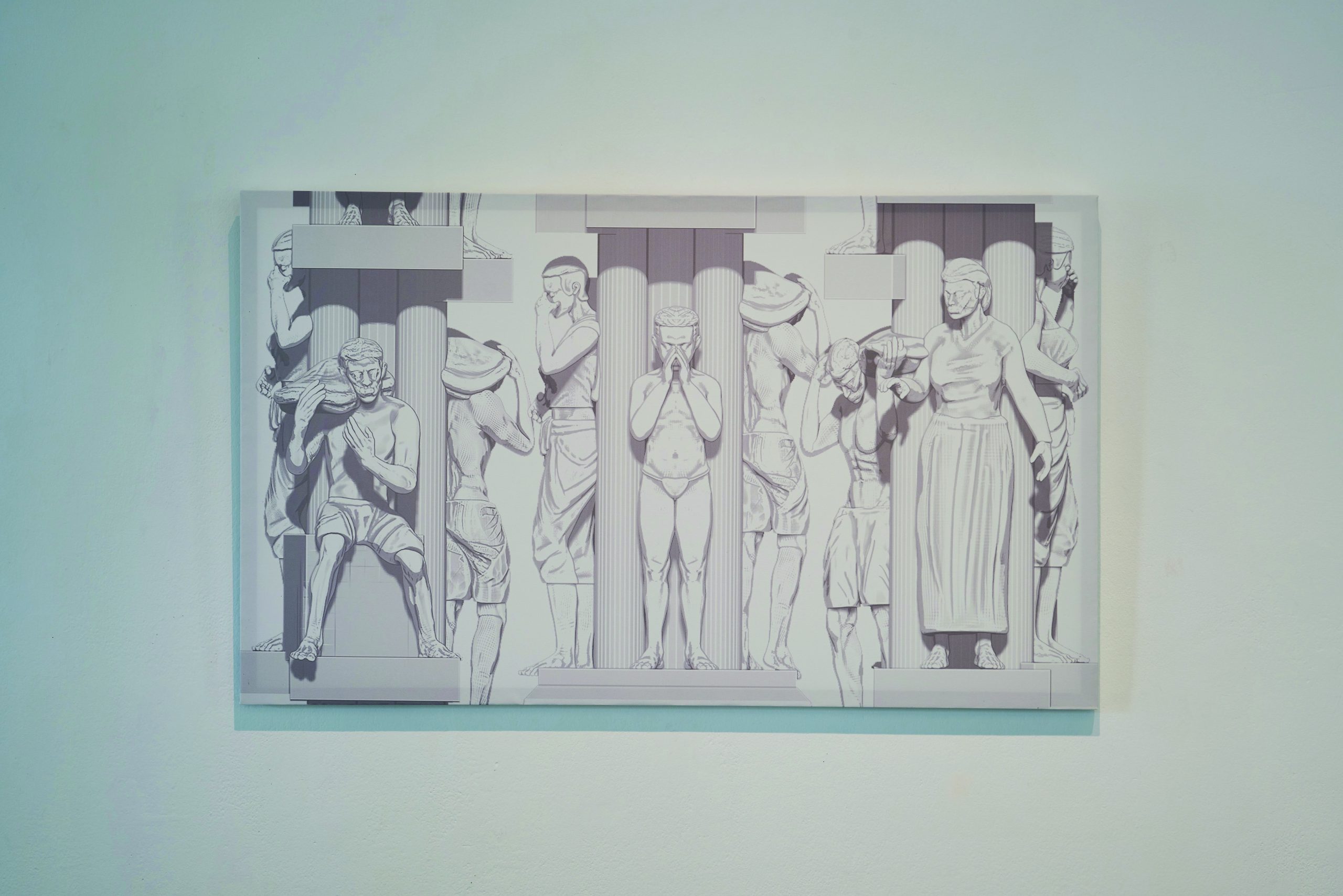

Moving further into the gallery, visitors encountered different approaches to the medium of sculpture. Anne-Laure Franchette investigates vernacular objects built by workers out of leftover materials on construction sites in the post-industrial Swiss city Winterthur. The toolbox in the exhibition was an enlarged replica of one of the transitory structures, a toolbox alongside the painted logo T.T (Travaux Temporaires/Temporary Works), that stands for artist’s archive of DIY built structures, tools and materials (Fig. 12). The Bandung trio, Tromarama, were intrigued by an enigmatic work from the LASALLE’s collection, a wooden statuette depicting a figure. There is no information recorded in the collection about the author of this work and its year of production. Despite the questionable provenance and its impact on the value of this artwork, the artists put the sculpture under the spotlight. Not only did they display it in the exhibition but they had also created a faithful reproduction with the use of 3D printing that sat next to the “original” (Fig. 13). Waret Khunacharoensap’s print on canvas was a representation of a fictional public monument (Fig. 14). Who is sacrificing? asks the artist, essentially questioning how Thai monarchy reinforces certain myths through the manipulation of its public image.

Fig.14

Waret Khunacharoensap, Who is Sacrificing? print on canvas, 60 x 100 cm

Fig.15

Marko Stankovic, 2020, 2021, glass, plywood, aluminium, 200 x 220 cm and 40 x 79 x 79 cm

Marko Stankovic’s new sculpture was a personal response to the unfolding of events in 2020 in the formal language of postminimalism (Fig. 15). Endowed with design qualities, the sculpture blended in with the wider campus architecture. Set against the built campus environment was the abstracted landscape of Cornwall’s coastline landscape explored in Laura Hopes’ video (Fig. 16). The area captured by the artist is well-known for deposits of what has been coined “china clay” or kaolin. Since its discovery in the 18th century, it has led to the development of a global porcelain industry.

Fig.16

Laura Hopes, Lacuna: Colour of Distance, 2016, high-definition digital video, 4:54 mins

Fig.17

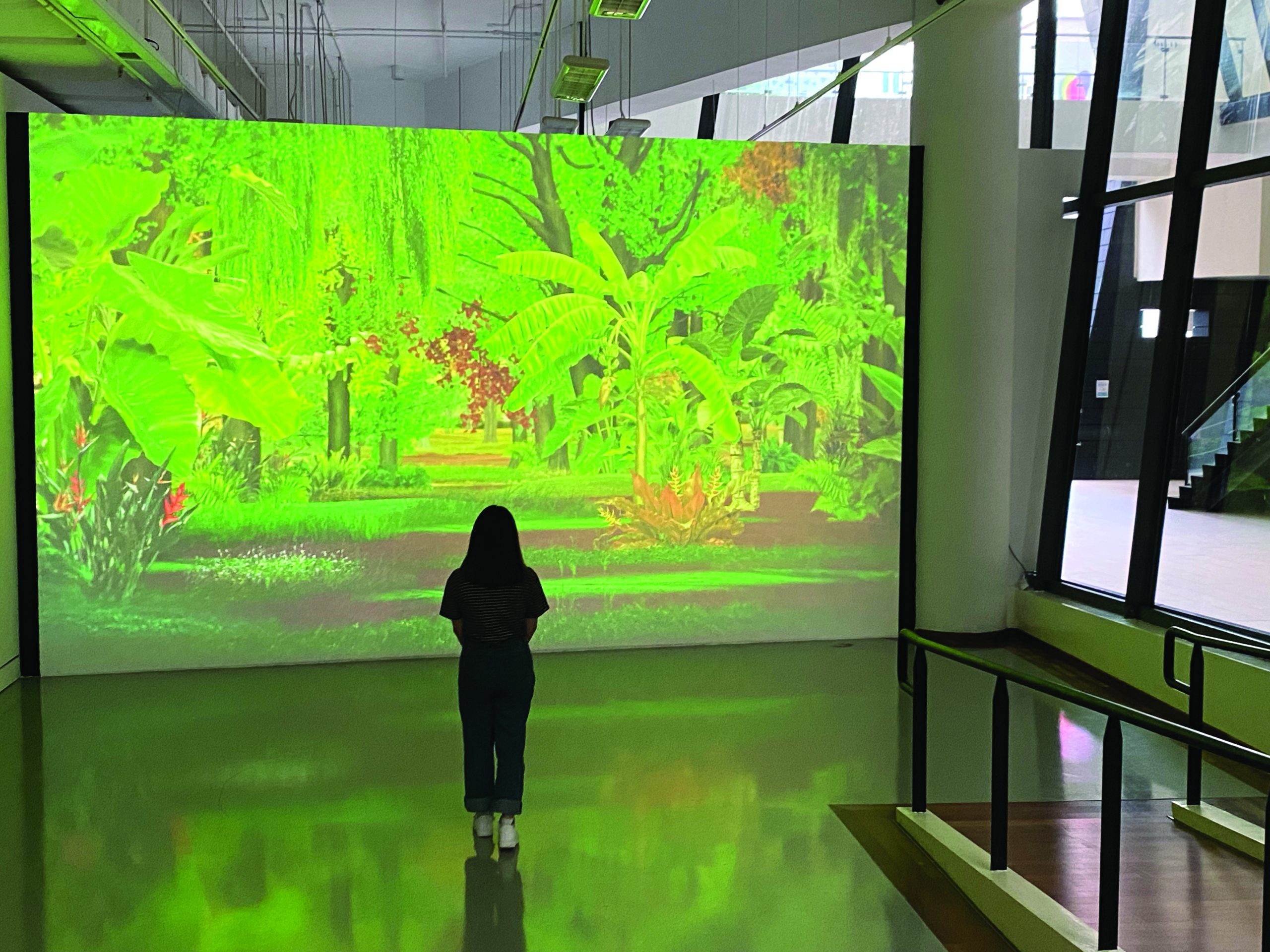

Danielle Dean, Private Road, 2020, high-definition digital video, 4:00 mins

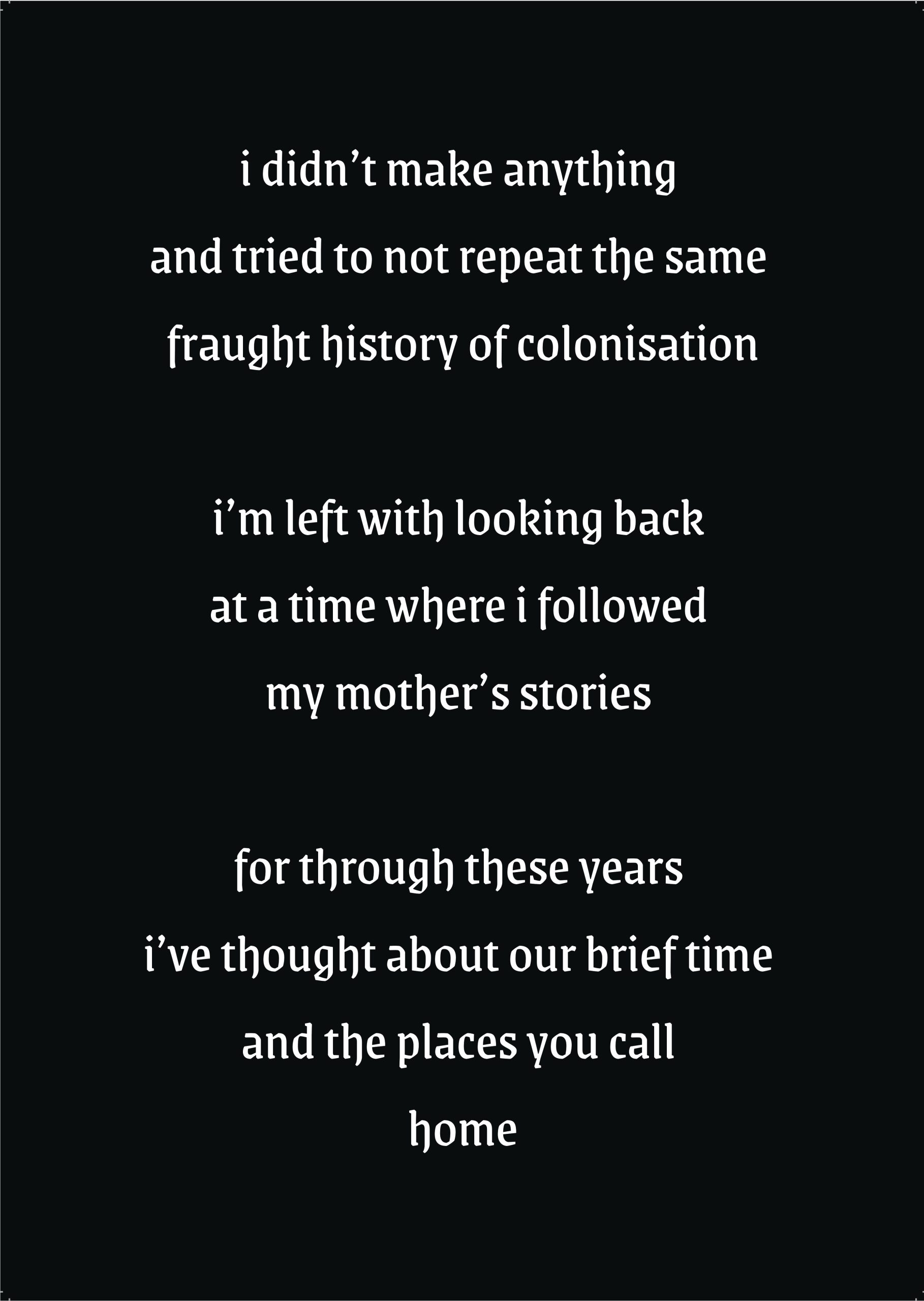

Danielle Dean’s seductive and deceptive animation, added another perspective on environmental exploitation and gave an impactful aesthetic form to a political narrative. From a picturesque image of the North American forest captured in a 1965 Ford Lincoln “Continental” print ad, the artist ‘drove’ the viewers further and further into the forest that morphs into a tropical rainforest akin to the Brazilian Amazon. This seamless transition highlighted the invisible ramifications of multinationals and their exploitation of resources (Fig. 17). James Tapsell-Kururangi’s discrete stack of posters on the floor was a gesture of resistance and position towards the pressure of high-productivity and its colonial undertones that the artist apprehended during his visit to Singapore. (Fig. 18) The statement in the poster gave voice to contestations and frictions that are inherent in any cultural exchange.

Fig.18

James Tapsell-Kururangi, Untitled, 2021, text, 42 x 29.7 cm. Courtesy the artist

Project Space

Project Space was tuned to a more alert rhythm. Set next to each other, two artworks produced between two distant cities, Brooklyn and Jakarta, transposed the shared experience of isolation as brought on by the pandemic. j.p.mot Jean-Pierre Abdelrohman Mot Chen Hadj-Yakop reproduced the experience of confinement in an augmented reality app made using the ceiling of his studio, photogrammetric capture, and blue corn tortillas (Fig. 19). Echoing all the video calls (which were normalised during the pandemic), this augmented reality app defied physical boundaries and teleported the artist into the gallery space. Hariyo Seno Agus Subagyo’s video directly captured the experience of alienation and social isolation produced by Covid-19 in Jakarta (Fig. 20).

Fig.19

j.p.mot Jean-Pierre Abdelrohman Mot Chen Hadj Yakop, I love hummus, 2020,

Augmented Reality app and Maxon Mills Ceiling RM.6, [41.8058° N, 73.5606° W], print, 111.76 x 88.9 cm

Fig.20

Hariyo Seno Agus Subagyo, Alienation, 2021, digital video, 1:31 mins

Fig.21

Kay Mei Ling Beadman, Dress Coded, 2021, 5 photographs, 87.5 x 58.4 cm. Photographs by Lin Jun Lin

Two other works in this gallery were grounded on biography. Drawing on her Chinese and white English mixed-race identity, Kay Mei Ling Beadman’s work is an inquiry into the complexities of identity formation and constructed racial hierarchies. The silver and golden metallic cloaks in the five performative photographs are markers of identity that question the problematic ideas of the 19th-century treatise Datong Shu by Kang You Wei. Despite progressive political views, the scholar proposed a eugenic super race of Chinese and white mixedness (Fig 21). Christine Rebet’s jarring animation delved into the psyche of her father, a former soldier who fought in the Algerian war. The war which unfolded between 1954-1962 was well-known for its guerrilla warfare and acts of torture. Disrupted figurative imagery, splashes of colour and piercing sounds translated for the screen the trauma of the war (Fig. 22).

Fig.22

Christine Rebet, In the Soldier’s Head, 2015, animation, ink on paper, 4:24 mins

The tour ended or could start right here.