Introduction

Throughout time, artists have expressed an understanding of the world and the immediacy of their lives through travel. The wandering journeys of artists shape the way the world of art is imagined, for they wander beyond physical movement: they wander existentially. A portion of the title ‘wandering journeys’ inherits a contradiction. Wandering presumes, to a degree, aimless meandering, while a journey is destined to a place or space. Together, they enunciate a dialectic: the artist as an observer and participant of the everyday traversing both spatial and temporal geographies. In some ways, travel enables them to work outside the rational arrangement of institutions as formalised enterprises. Perhaps there is an inner rebellion. To work with institutions and yet not within them is wrought with paradoxes. Travel shapes what artists may become, reaffirming an oft-forgotten principle that art is more than mere visual expression. It is a continuous search for a language to express one’s being. While the current condition to travel is vested in social and digital media, at different stages of their travel, artists arrive and depart, enter and exit. They do so to pause and to meet like-minded artists. In situ, they learn, explore and deliberate.

The enabling of travel and congregation was seeded through art schools and academies in the last century to inform artist-learning through casual and informal gatherings as conducive zones of free expression and creativity. It was a fundamental place to hone one’s criticality and bolster the kinds of stories they wanted told. However, contemporary expressions of travel and congregation are no longer exclusive to arts schools and academies as they have been abundantly embedded within museums, biennales and galleries and as competitive residencies and fellowships to support a growing investment in art. Amidst this broad sweep of a transformation, what kinds of new points of inquiry emerge for the artist? This essay muses on some possibilities through the study of Tropical Lab in Singapore.

Arts Schools

We know what we are but know not what we may be.

– Hamlet, Act 4 Scene 5, William Shakespeare

Arts schools1 were founded on the belief that art transforms the individual, the community and society, thereby contributing to a civic and national consciousness. This is located within an Anglo-European philosophy of self-determination and self-realisation expressed most pronouncedly by the philosophical renditions of Êcole des Beaux-Arts (Paris), Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Antwerp) and the Staatliches Bauhaus (Weimar). Across the Atlantic from Europe, named art institutions were established by individual philanthropic, business and educational magnets (Pratt, CalArts, Parsons, etc.), to blend visual and graphic arts to support a fast industrialising America that was responding to a new zeitgeist of contemporary expressions.2 Asia and its myriad of artistic and creative traditions built the arts around craft, livelihood and sustainable traditions. From Istanbul to Yogyakarta and Baroda to Xi’an, artistic traditions were custodial to enshrining and preserving cultural practices through loyalty, patronage and kinship-based community systems. Modernity through colonialism, as problematic as it was, swept through Asia, instilling a pivot to artistic traditions centred on creative genius, identity formation and self-representation. Postcolonial societies cautiously embraced the potency of modernity as the rise of industrialisation was fast entrenching systems of governance, education, economy, and ways of living.

Through a sense of independence, a commitment to a philosophy of practice, a dose of maverick potency and rich culture of making and doing, arts schools remain bastions of artist journeys and facilitators of creative congregations presenting a broad menu of learning approaches to suit varied interests. They remain intense and sometimes self-inflicting while unlocking creative potential. Two examples emerge.

The Black Mountain College, USA, founded in the 1930s, is a short-lived yet potent art school. A destination space for nomadic artists who resisted increasing bureaucratisation of art and education, it became a site that birthed a new curriculum focused on interdisciplinary and experimental practices and a deep commitment to making.3 The College functioned for all but 24 years—perhaps it does not matter how long one is around—and ‘graduated’ the likes of choreographer Merce Cunningham, composer John Cage and visual artists Josef Albers, Walter Gropius, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Willem de Kooning. Their impact on the avant-garde reverberated throughout the decades and is still felt today.

On the other side of the world, Kala Bhavana (Institute of Fine Arts), founded in 1919, is located in Visva-Bharati University. Founded in the thick of British colonisation of India by the family of Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, he led it to significance. Located in a remote hamlet, Shantiniketan, in West Bengal, it became a centre for thinking through a postcolonial India. It was critical to formulating a pan-national identity through an innovative new curriculum. The institution resisted the dictate of colonial education and fostered the belief that “education should not be dissociated from life.”4 Economics Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, an alumnus of the school, expressly shares that “the emphasis here was on self-motivation rather than on discipline, and on fostering intellectual curiosity rather than competitive excellence” and that artists worldwide, particularly from China, Japan and the Middle East, travelled, resided, taught and created works, studied with faculty and explored new ideas.5 World-renowned Chinese ink painter Xu Beihong was one of the first visiting artists to Kala Bhavana in the late 1930s to explore a new way of thinking about art through transnational exchanges.6 The work of teaching faculty and graduates of Kala Bhavana continues to influence how transnational ideas should be central to the curriculum. These include 20th-century luminaries: visual artists Nandalal Bose, K.G. Subramanyam, Jogen Chowdhury, Ramkinkar Baij, film-maker Satyajit Ray and art historian Stella Kramrisch.

The two examples above were built upon the belief that artist learning points are dissimilar to conventional science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which builds a seamless progression of acquisitive information, synthesis and application to create an impact on society. However, modernity’s cruel play on arts education, predicated on this scientific and universal mode of learning, formalised artists’ continuous inquiry into modern-day lifelong learning and creative output into learning outcomes. Despite this, arts and artist education continued its transformation well into the 1990s. Artists’ learning points do not progress seamlessly and sequentially but rather through a series of dense and, at times, spontaneous, informal and hybridised experiences with technique and technical skills, material study, exhibition-making, residencies, negotiated situations, walking, observing, recording, critiques, explorations and deductive applications, inquiries and post-inquiries and conversing and storytelling—all leading to developing visual diaries of new languages, practices and ideas informing art.

The rapid decolonisation of the world in the early part of the 20th century left vulnerable postcolonial societies exposed to the unfettered globalisation of their economies, cultures and systems. This bolstered the professionalisation of the arts and broadened the scope of art beyond its essential and intrinsic qualities, requiring it to extrapolate itself into another order—the marketplace.7 Art, hyper-extended off artists, became custodial concerns of collectors, galleries, curators and events; and, even tradeable through crypto art-financing schemes.

Globalisation is a double-edged sword: a contracted artist experience is also amplified with a myriad of new opportunities in fields far beyond self-realisation. Art in the contemporary world is here to stay and is all-encompassing, masterfully permeating through the everyday lives of people. The knowledge base of an emerging artist today is much broader in scope, and s/he has a deeper understanding of the economic spheres within which art finds itself. Yet, if globalisation has rendered artists speechless of their informal and experiential approaches, the arts school then becomes the enclave for them to wrest an alphabet just as a speechless Lavinia in Titus Andronicus sought to outline the violence inflicted on her.8 The arts school becomes a research and development site for the production and circulation of new beginnings and meanings while tapping on the new opportunities of the marketplace. Ute Meta Bauer cautiously opines: “Can you discuss the meaning of artistic production within the larger field of culture, or perhaps more precisely, debate what is culture today in such a globally expanded field of experience and how art schools have adapted to this fact?”9 The reality calls for the co-existence of the market (which could potentially determine aesthetics) and the arts school, which continues to drive the discursive meaning-making sphere where the debate is centred.

In an increasingly complex and highly-networked global environment that requires essential artist skills such as exploration, experimentation and self-discovery, the arts school has had to confront the bureaucratisation of arts education and deal with demands alien to its aesthetic considerations. This is not easy and has forced artists to move out of their studio, move around and rediscover. Gielen views, “mobility and networking are today part of the art world’s doctrine,” requiring artists to disembody from the comforts of their studios to discover and create new networks.10 As a community of artists evolves into a community of artist-scholars, artist-educators and artist-researchers, the arts school of the 21st century is also challenged by practical notions of self-sustainability and employability racing the artist from studio to gallery wall.11 In response to the bureaucratisation of arts education, self-organised artist residencies, camps and inter/national exchanges have proliferated throughout the world built around collectivism, shared concerns and spaces to create.12

As the dictates of employability and access beckon the sustainable future of artist education, creative cities, as a feature of globalisation emerge. Cities, imbued with a rich portfolio of infrastructures from galleries, museums to performance venues, serve as cultural meeting points with a plethora of events for domestic and international workers and visitors. Arts schools, on the other hand, while sustaining themselves as a mainstay of thought, ideas and creative processes have become an important—almost crucial—talent pipeline for the creative city. Supporting a creative city and living in it are two different ideas. In an attempt to bridge liveability (quantitative and accountable) and art (qualitative and experiential), recent globalisation policy discourses have shifted to creative placemaking. As opportune as it may be, arts schools followed suit. Arts schools either moved away from remote rural and suburban sites and relocated to city centre or became infused into the city’s downtown core (e.g. School of Visual Arts, New York; School of Art Institute of Chicago; Central Saint Martins, London; and LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore). They became intertwined into the ‘soft real estate’ providing vital sustenance to energise the city. While aiding artist education to remain grounded and global and hold vigil to the varied approaches to artistic curricula, artist camps and residencies emerged as responses to creative placemaking. Here, artists no longer had a quiet meditate residency but needed to engage with a pulsating city.

Lab Notes: Informal Pedagogies and Practices

Through others, we become ourselves.

– Lev S. Vygotsky13

Earlier I outlined dynamic, non-sequential and hybrid learning approaches of artists, much of which remains informal and self-directed. In a hyper advancing world where creativity is challenged to produce material outcomes, artist camps and residencies have become havens to articulate such nuanced methods of inquiry. But art practices play with ambivalence. They co-opt modernity’s scientific and universal forms of education and globalisation’s creative placemaking into their ambit and even risk being an apologist for venturing into the art marketplace without any sand to their elbows. For art is agnostic to all learning approaches and chooses to co-exist and hybridise the space of others. Arts schools are not friend or foe to the marketplace, to modernity’s pedagogy or globalisation’s interests—for art is not. It is in this context that an arts school organises an annual artist camp in Southeast Asia.

Tropical Lab14 is an art camp organised in an arts school located in the city-state of Singapore, known for its free trade and free movement of multicultural communities over the centuries. It pays homage to the equatorial nature of the island’s location: a sleeve north of the equator. The punishing heat and suffocating humidity of the tropics and the shimmering economic wealth of the city-state form a central backdrop to the art camp. Annually, over two weeks, 20 to 25 selected participants15 gather in Singapore to deliberate on a theme of the day.16 The approach is technically simple but conceptually complex. The participants are practising artists enrolled or recently graduated from school, generally at the MA/MFA and even PhD level. They have a substantial body of emerging work and a keen sense of the world around them. They are nominated by their respective institutions upon an open call. Each institution can only nominate one participant, sometimes but rarely two, through various internal systems of pre-selection in which the organiser does not participate. Nominations are sent to Singapore for consideration. Selected participants pay a small participation fee while the organisers subsidise participants from the Global South countries. This is key to ensuring a culturally diverse set of artistic practices and learned pedagogies are afforded to presence themselves amidst more dominant methods of artistic traditions and learned pedagogies as valid and appropriate. Participants have to primarily self-fund their travel, while food, accommodation, art materials and local transport are covered by the organiser for the two weeks. They are also provided free studio spaces.

Participants come from all over the world from a range of institutions, and in studying their profiles, they tend to be culturally diverse even in their home institutions. For example, past participants include a Mongolian studying in the USA, a Palestinian studying in Europe and an Australian studying in Vietnam. This transnational diversity is significantly pronounced in the arts school environment, reinforcing my opening remarks regarding the artists’ proclivity to traverse spaces and places. While the English language is the primary mode of communication in Tropical Lab, participants bring a rich plethora of formal languages of their cultures, enriching the camp.

Tropical Lab is organised in three interwoven yet parallel tracks that converge: sharing, learning and making.

Sharing entails two parts: A curated one-day seminar comprising papers and talks by invited artists, curators, architects, performers, theorists, scholars, art historians, researchers, etc., laying the ground for exploring the theme of that particular edition of Tropical Lab. It is also an opportune moment to understand the camp’s location and the mental, creative and philosophical space within which the participants will work. Following the seminar, an intense sharing of each participants’ art practice and creative journey ensues. Part autobiographical and part visual diary, it reveals the deeply held principles, concerns and convictions each artist has, providing a vital node for connectivity with others through their practice and opportunity to be self-reflexive and learn and unlearn through others.

While learning takes place during the sharing track, learning as lived experience is organised through site visits to various types of urban, suburban and rural spaces, events and exhibitions, artist studios and gastronomic explorations. Tropical Lab takes place in LASALLE’s McNally campus, a futuristic modernist architectural building notably contrasted by its location. The campus, located in the heart of the arts and civic district bordering downtown’s fringe, is nested centrally amid living and functioning cultural and heritage districts, Little India, Chinatown, Kampong Glam, Armenian and Jewish centres. A confluence of multiculturalism confronts the participants as they attempt to steal a conversation between the futuristic building and the heritage districts. Adding to this layer is the introduction of food. Food is akin to ‘welcome’ in Southeast Asia, but more importantly, a means to build an esprit de corps amongst the participants. Each lunch and dinner is carefully curated to provide a complete cultural arch. To learn about food is just as important as consuming it. For instance, food as a tool of affect, particularly in Southeast Asia, stands for hospitality, care and fellowship. The participants undergo a sensory assault of art, culture and heritage, urging them not to merely collect and centralise their learning to themselves but to dis-member their learned experiences from an economy of artistic centralisation to become one with others to learn as a community.

Finally, making. The artist studio that each participant is allocated is a shared space for participants to create their response to the theme. They are encouraged, but often self-motivated, to develop a work or body of work to be individually showcased in an exhibition. The creative process confronts the Lab environment as the making unravels in full view of others. The participants work through all they have collected and experienced, unpacking objects, sites, scenes—photographed, scribbled, and etched in the mind and social media. The intensity of making for these confident artists can be bewildering as they attempt to disassociate their presence as cultural tourists into a distinctive embodied self, located in a different time, place and space. The participants are provided with a modest material fee and have the opportunity to access the college’s workshops and equipment where needed. The works range far and wide in method, material and discourse, underscoring Tropical Lab’s agnosticism to artmaking processes. In the artist studio, works-in-progress are sighted and critiqued and curated by the director of The Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore (ICAS) into a consummate public finale. The exhibition opens at the end of the camp at the ICAS’ main galleries, just as the artists pack and depart. Some travel home, some stay longer in Singapore, some commence an exploration of Southeast Asia. It marks the beginning of a new connected artist collective, a tribe.

Tropical Lab may seem an oasis of informality. However, in unpacking its approach, it is both intense and dense and differs substantively from other residencies and art camps. Instead of taking the most common route of providing studio space and leaving artists to their own trajectories, here the juxtaposition of sharing, learning and making within a period of dislocation, with limited time to scope the living environment, is challenging and life-altering. This is especially so when the participating

artists work within a series of mandates: an exhibitory mandate to create and display; a social mandate to gather, socialise and explore facets of a city-state; a cultural mandate to learn the multicultural dimensions of Singaporean society; a critical mandate to unpack past learned practices and perspectives (theoretical, historical or technical) to formulate the new; and, a personal mandate to see and be different. These mandates form the basis for an emerging community of practice, informed by listening and visualising through others and being subjected to extreme scrutiny by others. There is a danger that superficiality or fetishisation of the overall experience can reign supreme, especially when time is of the essence. As such, preconceived ideas and predetermined approaches are kept in check at Tropical Lab through detailed, almost forensic, conversations. Commencing with a sense of informality, the participants soon realise the profound structural opportunities Tropical Lab affords as they are provided with extraordinary access to subject-specific lecturers and tutors to deliberate their findings and impressions.

Sarongs, Gotong-Royong, and New Initiatives

At some point in the two weeks in Singapore, participants receive a sarong—a piece of tubular gender-neutral stitched fabric worn at the waist in Southeast Asia. It is a very affordable daily wear piece that is friendly to the hot and humid weather of the region. The fabric is called many different names, and its manifold manifestations can be seen throughout Asia, Africa and the Pacific islands. The sarong is synonymous with ikat and batik prints17 and motifs. It bears multiple uses from keeping one modestly covered, keeping warm, cradling a child, carrying goods and many others. Its use-value translates into a signifier of collaboration as traditional communities weave and create together. Collaboration in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and the larger hinterland is known as gotong-royong. It is a participatory strategy that helps individuals and communities to collaborate and help one another. It is an instinctual and existential practice, much of it blurred in the overt valorisation of individual subjectivity in modern society. Collaborations are as much work as fun. Each passing day is configured with activities and movement. It is exhausting and sober but elegantly punctuated with meals transforming into a bounty of joy, humour and discoveries. Here the individual emerges to just being, as conversations are re-rendered, becoming leitmotifs of oral histories. This is a feature of gotong-royong, which foregrounds horizontal alignments between communities and people—creating fluid movement between ideas, identities and experiences through conversations heard and overheard as they continuously open their borders to invite outsiders from within and without.18

Gotong-royong for the participants can relieve them of their anxieties around the demand to produce art. It facilitates them to explore and dispense with the centrality of their subjectivity collectively. Ultimately, though participants have collective experiences, they produce individual responses which differs markedly from their taught practices from school, as described by the volume of past participants. Many seek to return to Tropical Lab to recalibrate themselves. It would be possible to read this need to return on two fronts. First, it is a manner of recounting the experience within a congregational framework of folkloric tales, legends, art and anecdotes (e.g. the Tropical King19), thereby building a tradition around Tropical Lab. It is a romantic idea—one that dangerously skirts around nostalgia and novelty antithetical to the Lab’s intent to bring new and diverse individuals together. Alternatively, it could be read as the emancipated artist’s mind desirous of furthering its repertoire of experiences through renewed participatory activities, inquiries and a sheer desire to meet others. Both remain valid as they speak to the formalisation of that which is informal and experiential.

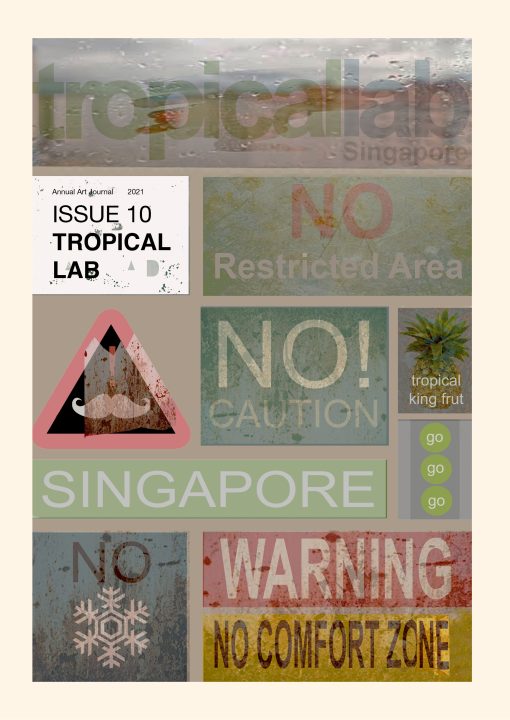

Some manner of formal activities did emerge. Tropical Lab birthed two new initiatives in the spirit of sharing community practices: Baby Tropical Lab and ISSUE. Baby Tropical Lab takes each year’s central theme. It develops into a one-week workshop for high school students across Singapore and their art teachers to explore art-making processes through collaborations across schools. Running it for more than five years has brought about students’ understanding of resourcefulness and resilience and the artist journey, as evidenced by the annual feedback from the participants. Secondly, in preparing participants to come into the Tropical Lab proper, pre-reading material was provided since 2005. These pre-reading materials melded with the seminar proceedings to become a reflexive, peer-reviewed art journal ISSUE since 2010.20 These have become anchors to this global camp.

It is essential to recall why Tropical Lab warrants study. Its approach to intensive study through informal practices and collaboration is transformational. It awaits scrutiny as a dissertation and now, at best, serves to be a prolegomenon on informal arts pedagogies and practices. While it awaits its turn, it remains of interest to the intrepid artist on a continuous search to emancipate, innovate, diversify ideas, and one who is outright curious.