VOLUME

ISSUE 05

Fictive Dreams

A play with a dreamscape where a new fictional world interplays rapid dreams, digital desires and humorous nightmares resuscitating flailing histories and memories of an expired epoch. It is a moment where art seeks contingency over agency; mobility over fixity; and burial over excavation. In this Issue, artists, curators and scholars traverse land and sea; cities and communities; ideas and ideologies; and images and imaginings to mediate on multiple notions of histories, geographies, politics, economies and aesthetics: thereby producing a rich reflection on an emerging new world/s through the lens of art and its imagining.

ISSUE 05

2016

Fictive Dreams

ISSN : 23154802

Introduction

Essays

Exhibition

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Introduction: Fictive Dreams

Essays

Lucid Dreaming

Subjects in the Mirror are Closer than they Appear A Post-traumatic Fictive Dream Disorder (PTFDD)

After Russia

Porous emerald

The Feminine Art School

Exhibition

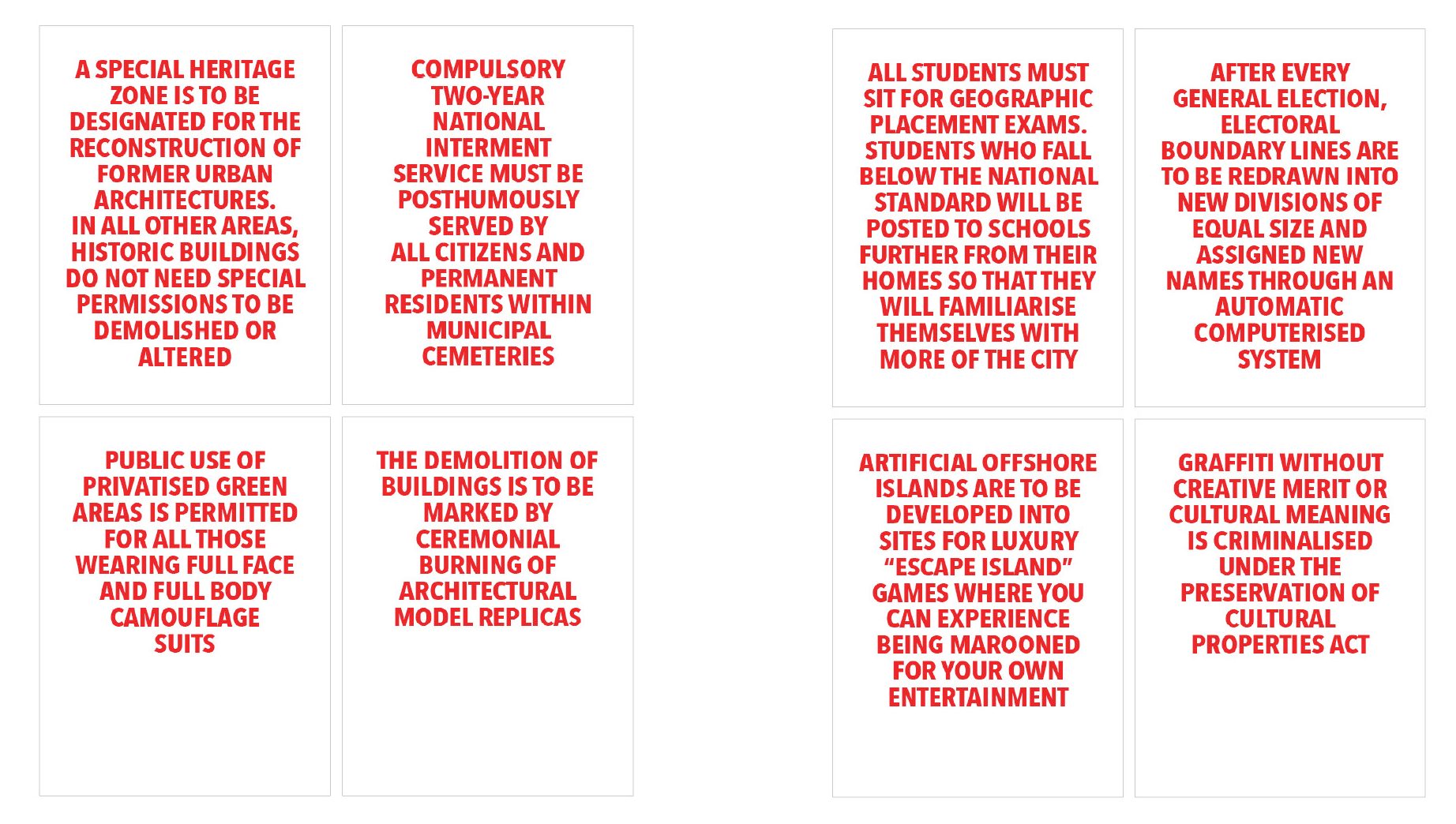

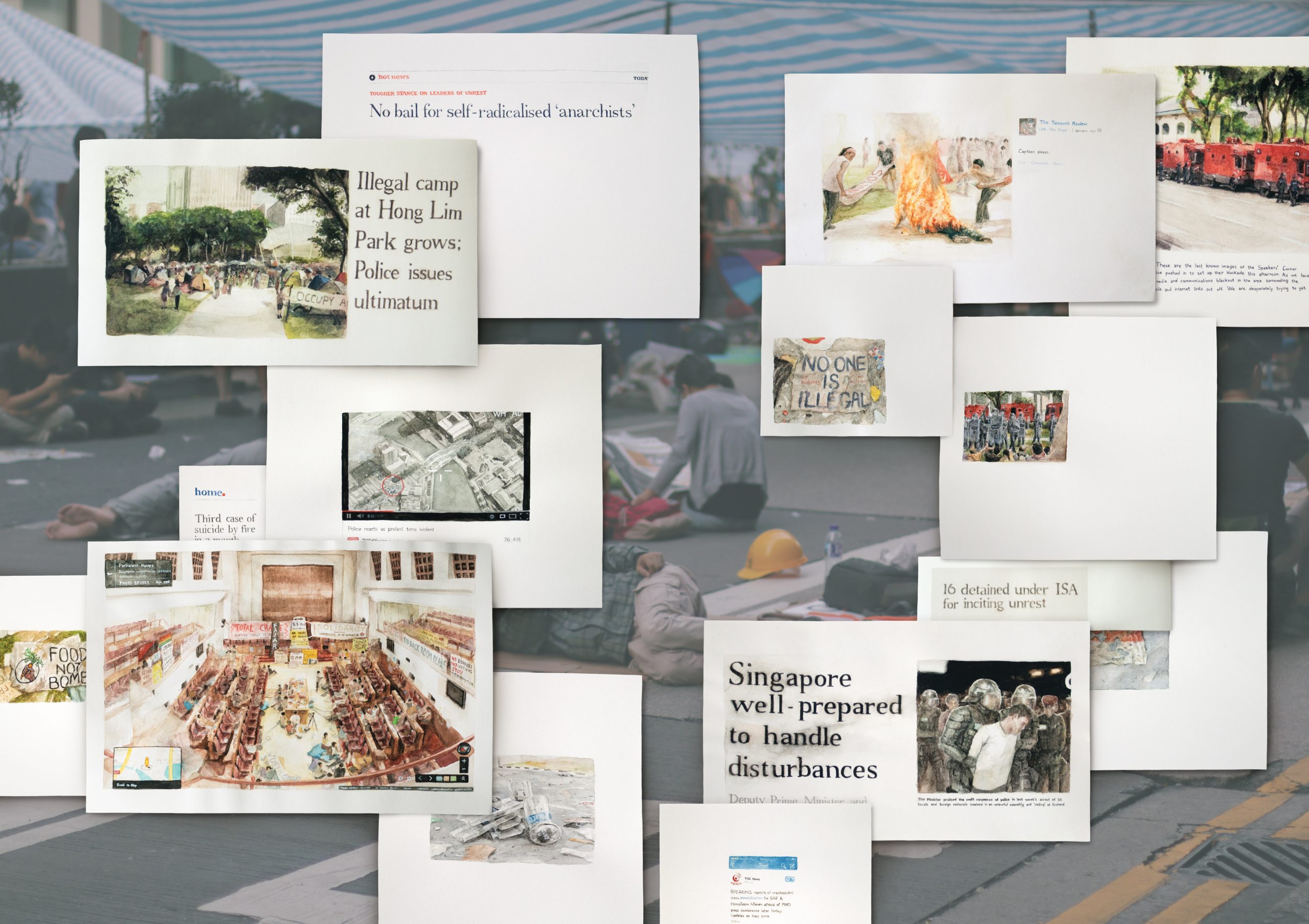

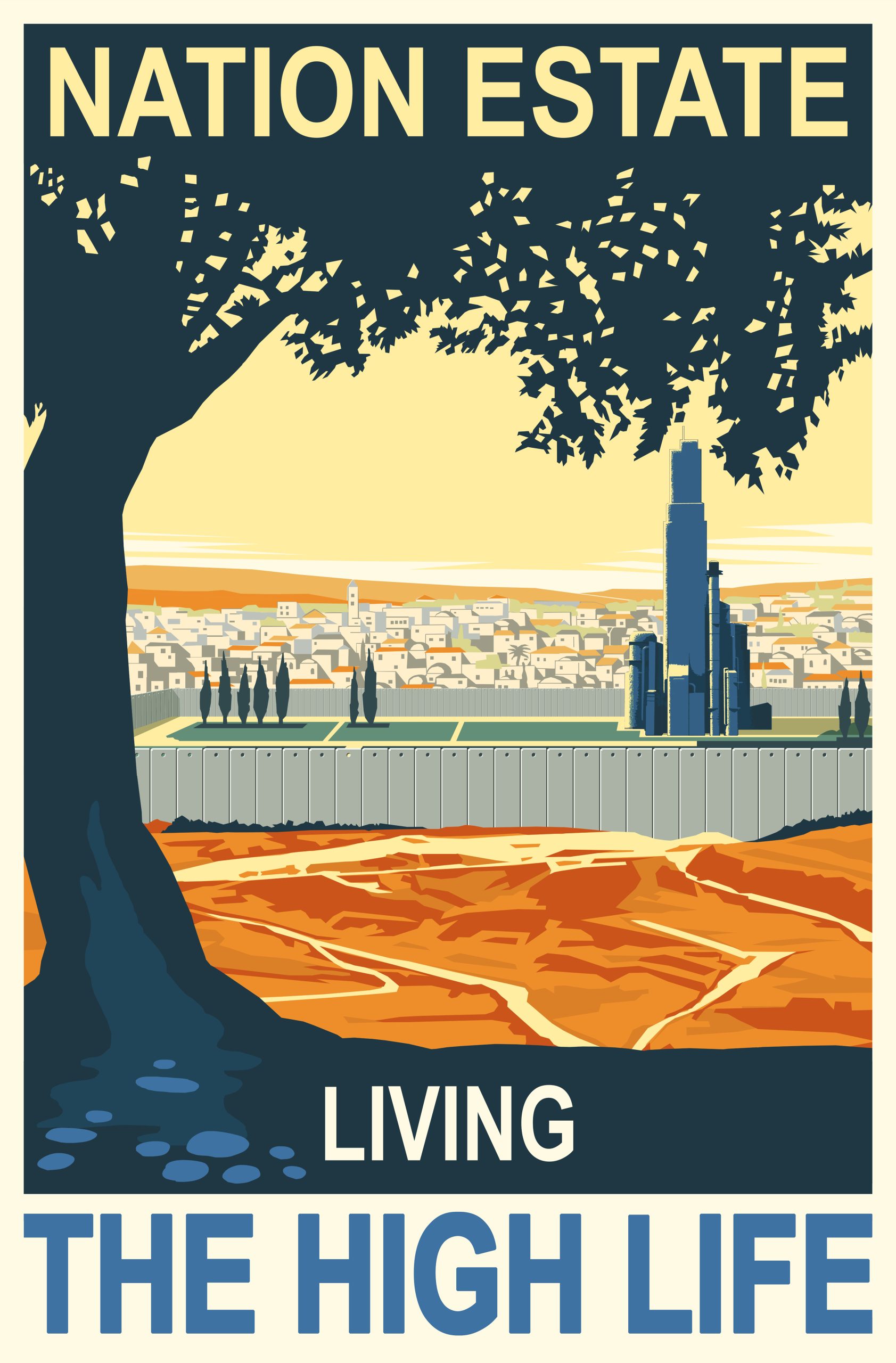

Oneiric speculations

Contributors’ Bios

Contributors’ Bios

Introduction

Editor

Venka Purushothaman

Associate Editor

Susie Wong

Copy-Editor

Lisa Cheong

Editorial Advisor

Milenko Prvački, Senior Fellow

LASALLE College of the Arts

Manager

Layna Ajera

Contributors

Steve Dixon

Tony Godfrey

Peter Hill

PerMagnus Lindborg

Chus Martínez

Bjørn Melhus

Charles Merewether

Rubén de la Nuez

Silke Schmickl

Isabel de Sena

Jovana Stokic

Introduction

Introduction: Fictive Dreams

The issue for 2016 is Fictive Dreams.

As the ink on the epitaph of globalisation dries, the world’s nations reel from an unknown future. A future that is only experienced through the rise of a nationalist inclination in a number of countries; the potential breakdown of trade and people to partnerships; the great migration of people despite rising border controls; and recycling of late 20th century artists and their aesthetics as a new frontier of the future.

In an unevenly even period of a meta-historical fissure, what foretells a future outside of fear, terror and breakdown? Is there a future in the real?

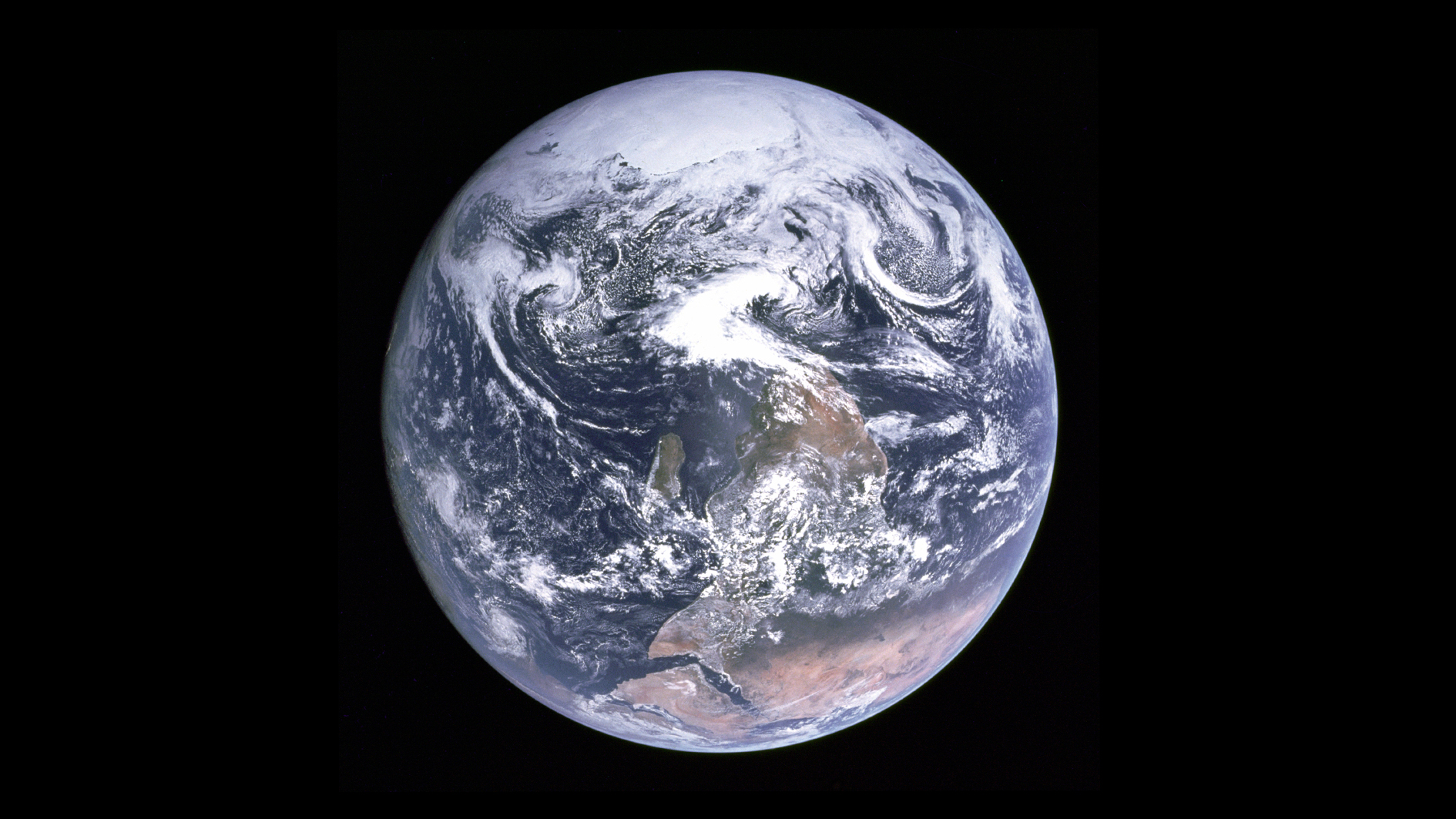

A new fictional world interplays rapid dreams, digital desires and humorous nightmares resuscitating flailing histories and memories of an expired epoch. It is a moment where art seeks contingency over agency; mobility over fixity; and burial over excavation. A new de-ideologised dreamscape unfolds as old myths magically dissipate and welcome a blurry sequence of imaginings of the real. Strangeness unfolds. We no longer know our neighbour. As the 21st century foregrounds a world of global human movement and mobility (deterritorialised as citizens) and presents postmodern warfare on lives, nature and the human condition, a need to imagine a new world is urgent. What is the future of the world?

In this Issue, artists, curators and scholars traverse land and sea; cities and communities; ideas and ideologies; and image and imaginings to mediate on multiple notions of histories, geographies, politics, economies and aesthetics: thereby producing a rich reflection on an emerging new world/s through the lens of art and its imagining.

Essays

Angels that visit in your sleep

A night in November 2015

What do you do when you can’t get to sleep?

You toss.

You turn.

You pummel the pillow to make it more comfortable.

You get up and adjust the AC.

You wander off to the fridge and drink some juice.

You settle down again.

Still can’t sleep.

Wander back to kitchen and pour yourself a whisky.

Check the late night news as you sip it.

Go back to bed.

And try and get to sleep by making a list,

Boring yourself to sleep, basically.

I really like making lists.

All the artists whose name begins with R; Rembrandt, Raeburn. Romney, Remington, Rothko, Rubens, Rosso, Rosso Forientino….

All the Swiss artists you can think of: Fuseli, Hodler, Pipilotti Rist, Scherer, Cuno Amiet, Urs Graf, Martin Disler, Thomas Hirschorn…..

All the Filipina artists I know: Geraldine, Wawi, Yasmin, MM, Nona, Jeona, Nikki, Ringo, Elaine…

It normally works: you rarely finish the list.

But it isn’t lists that really matter:

It is the strangeness of particular art experiences which come floating back again as memories once you enter that liminal state between consciousness and sleep.

Those experiences that James Joyce described as epiphanies.

“Its soul, its whatness, leaps to us from the vestment of its appearance. The soul of the commonest object, the structure of which is so adjusted, seems to us radiant. The object achieves its epiphany,” he wrote in Stephen Hero, Chapter XXV.

These radiant angels of the night are the memories of when and where artworks or environments have taken over, entering your consciousness like god speaking to the magi, or like Gabriel bursting into the room.

(By the way, I love this Annunciation by Lorenzo Lotto. Such an urgent, imperious archangel Gabriel, such a scared but devout Mary, such a bustling God and such a great cat running away.)

Rothko is the name that would often bubble up in this discussion now.

Lorenzo Lotto. Annunciation, 1534

I have been to the chapel in Houston and it is a wonderful place, so gloomy, so dark, so melancholy. It is without doubt the best funeral parlour in the world, but where he got me was back in the 1980s when I had arranged to meet someone in the last room of a retrospective of Rothko at the Tate then. She was late so I sat there a long time reading the catalogue until the paintings began unexpectedly to affect me – they worked on me even though I wasn’t consciously looking… Perhaps because I was not consciously looking. I was taken away by them. Yes, it was somewhat sombre, but it imbued a sense of contentment, of grace.

Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal son. It took my breath away in 1981 when I went to the USSR and saw it in the Hermitage. It is the humanity of it, the father accepting back the wastrel son and the way it is conceived as figures and faces emerging in the dark. The clumsy hands. The threadbare garments. Faces in the dark.

The same trip, the same museum but a very different epiphany: Matisse. Not just The Dance but also Music, the companion painting on the opposite wall. The girls dance, the boys sing. And in between, a small, intense painting about the colour red. It was of a woman in an interior, but it was about the colour red and the way it shines and sings. It was the complete experience. Painting has to be installed right to really work.

And in the right place. The journey to see something is part of the experience. People talk of the Piero experience as a pilgrimage. Yes. You drive for hours through country to get to see the one painting by Piero della Francesca – the Madonna del Parto in Monterchi. I went in the 1980s. It was wonderful. The painting was in an old church next to a cemetery. It had been moved from a part of the church that had been destroyed and it had lost its old margins – it was a fresco. But it was still beautiful… and peaceful… and humble. But I went again maybe 15 years ago and it had been moved to a special museum funded by Olivetti with lots of audio-visual explanations and a gift shop and it was behind bulletproof glass… there was no aura left… conserved, preserved and dead.

Rembrandt. The Return of the Prodigal Son, detail, 1669.

What of this region we live in? I can think of three occasions when something happened like this.

Firstly when I went to – of all places! – Novotel in Bandung. Handiwirman had made a sculpture for each floor of the hotel based on the sort of things you see in hotel rooms – coat hangers, radiators, towels, taps…. It was not so much witty as delicately done. Fingertip precision. A sense of how the most banal thing could be transformed into something strange and beautiful. That can be when an artwork becomes an event in your experience – like a song floating over the meadows or the evening sun setting fire to all the clouds: orange, red, purple, to darkness.

An experience of Agus Suwage’s Pause replay when I saw it at his retrospective in 2009 was equivalent but very different. In a way it is an intellectual work examining the West from the East, performance art from the viewpoint of a painter. But the facture – the way it is made – the lyricism of the watercolours makes it. I was absorbed for I don’t know how long – of course, part was the fun of spotting what I recognised, but there was something else – what Rilke would call “praise” in the way he depicted all these people, performance artists, doing odd things.

Handiwirman Sapoutra. Sculpture in Novotel, Bandung.

And sometimes this can happen in the most unlikely place – such as Christie’s sale-room in Hong Kong 2010. Everything is inevitably hung higgledy-piggledy in such a context and being presented as commodity anything like a spiritual or quasi-spiritual experience is most unexpected. But when I saw a painting by Geraldine Javier (Ella amo’ apasionadamente y fue correspondida or For she loved fiercely, and she is well-loved, 2010) I was absorbed. I did not know her then. The distortions in scale. The introspection. The stiff mask-like way the figure was painted. All bound together. It calls for meditation, for silence, to no longer hear the ticking clock. And the sense of mourning in the mediation turns to one of reparation.1

When did this sort of experience happen to me more recently: this sense of absorption, of time stopping, of intense beauty or grace? Last summer: Joseph Cornell in the upstairs gallery at the Royal Academy in London. The works are so small, so intricate in their making that it is like letting go and entering into a doll’s house, but then looking out again at the world with wonder. And everyone else there was enjoying the show: that was important. Sometimes this is not a wholly solitary experience but one shared.

I went a second time to the Cornell show, but it didn’t have the same effect. That is often the case. Epiphanies aren’t on tap.

I sleep deeper. Other epiphanies may return too, like lonesome angels searching for a home to sleep in: Kiefer at Zeitgeist, Donald Judd’s one hundred cubes at Marfa, Texas or Robert Wilson’s 1993 installation in Venice.

But I don’t know: I cannot recall dreams from deep sleep.

Another night, December 2015

Faces that haunt

When you sleep you dream

And when you sleep what is it you are most likely to see?

A face

It is probably a human face looking back at you.

Sometimes with body, sometimes without.

Perhaps it is a ghost, or a memory of someone you knew, or a presentiment of someone you will meet

They appear just as in Shakespeare’s Richard the Third, the ghosts of those he has killed appear:

Enter the Ghost of Prince Edward, son to King Henry VI

Ghost of Prince Edward

[To KING RICHARD III]

Let me sit heavy on thy soul to-morrow!

Think, how thou stab’dst me in my prime of youth

At Tewksbury: despair, therefore, and die!

Enter the ghosts of the two young princes…

Enter the ghost of Lady Anne his wife…

The 18th and 19th century artists loved drawing and painting this scene: Hogarth, Abildgaard, Stothard…

They demand vengeance – those ghosts. Fortunately, my ghosts demand nothing. As far as I am able to remember my dreams, they just look and say nothing.

Here are some faces that may appear in my dreams.

(By the way, I have a very bad memory for faces and names. It doesn’t get better with age. A few years ago I started to photograph artists when I first met them and ask them to take a photograph of me. But I normally forget to do it. When you first meet people you are too focused on what they say, their body language.)

Of course, I don’t just dream or think of people in Southeast Asia. That would be an absurdity. I dream, as I think, globally.

Wawi Navarozza, 2011

Tintin Wulia, 2011

S. Teddy, 2012

This essay derives from two talks given at Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore. I thank them for their invitation and also to Ian Woo for playing bass guitar as I gave the first talk.

Images courtesy of Tony Godfrey.

And I dream of the dead. Those who we knew who are dead still live in our memory. In a way in our dreams they seem the most alive.

I dream of my brother Richard. I dream of my parents. I dream of my primary school teachers. No doubt now S. Teddy has sadly joined them on the other side, he will visit in my sleep too.

I dream of the dealer Nigel Greenwood who I knew well in the early ’80s. He was fun to be with: informed, witty and enthusiastic.

I didn’t see so much of him once his gallery closed but was sad to hear he had developed cancer and died 12 years ago. I was told that near the end, after the normal hopeful encouragement and reassurance that doctors offer, he realised there was no chance left.

“Am I about to die?” he asked.

“I am afraid so, Mr. Greenwood.”

“In that case can I have a glass of champagne?”

That was his attitude to life. Maybe I should write a book on art with that as the title. As a philosophical statement with which to march into the darkness it is as good as any.

Footnotes

1 Now in the collection of the Singapore Art Museum

Essays

Lucid Dreaming

Figure 1. Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1782

Introduction: Artists as Lucid Dreamers

Dreams are one thing everyone has in common. As Jack Kerouac put it: “All human beings are also dream beings. Dreaming ties all mankind together.” Martin Luther King had one – perhaps a more iconic one than you and I — but we all have them. Artists of all disciplines have explored them for millennia, depicting ‘fictive’ dreams far more visionary, startling and disturbing than everyday reality. That, of course, is their appeal.

“A book is a dream that you hold in your hands,” wrote Neil Gaiman, and dreams themselves have been a running theme in literature for centuries, from Shakespeare’s insight that we are made of the very “stuff” of them, to Edgar Allan Poe’s insistence that: “All that we see or seem is but a dream within a dream.” Jorge Luis Borges wrote of our sadness when being awoken abruptly from a dream, feeling robbed “of an inconceivable gift, so intimate it is only knowable in a trance.” Poets have feared them – Samuel Taylor Coleridge frequently woke his whole household up with his screams – and eulogised them, W.B. Yeats implored a lover not to tread on his, and John Keats declared that: “We need men who can dream of things that never were.”

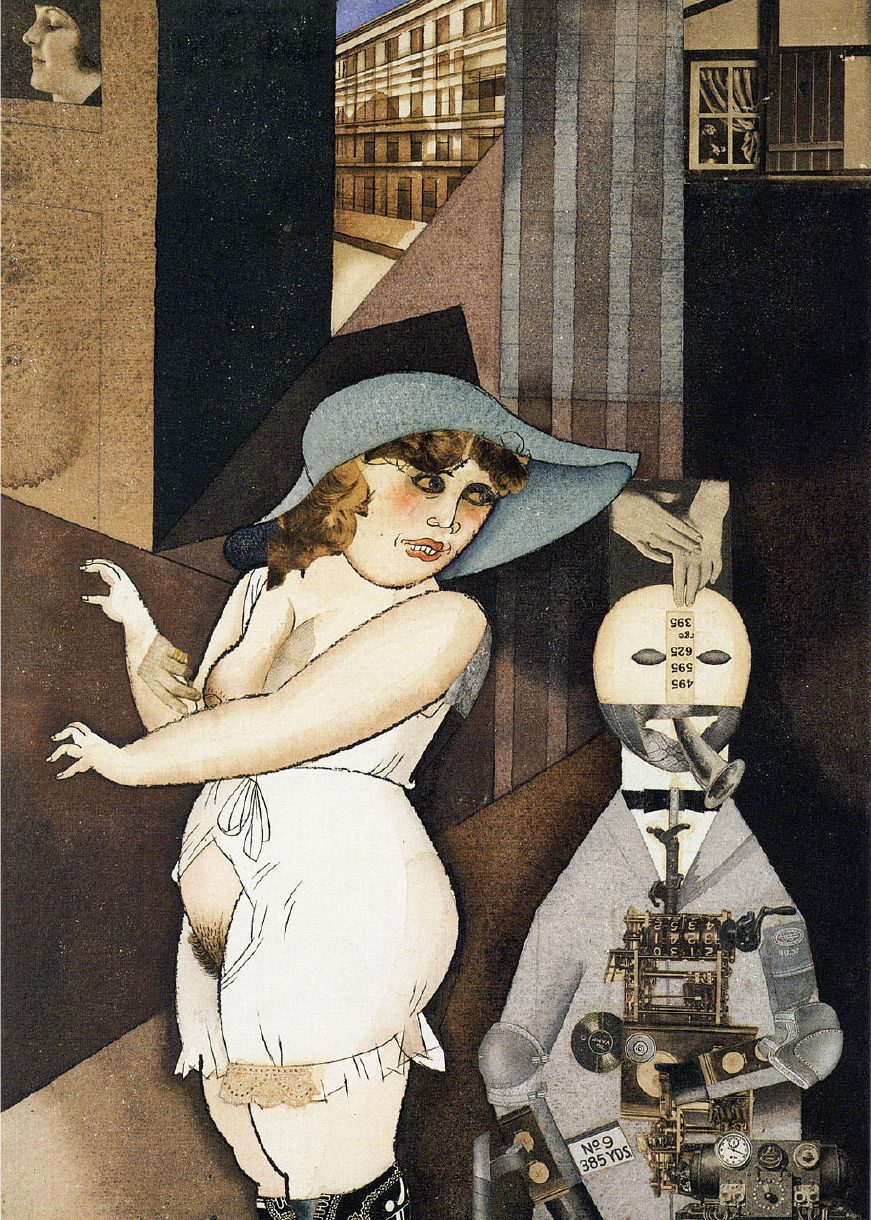

In the history of Fine Art, dreams have both inspired – like the Byzantine depictions of Jacob’s Biblical dream of an angel-filled ladder bridging heaven and earth — and elicited fear, as in the hellish 15th century nightmares of Hieronymus Bosch, or Henry Fuseli’s demonic goblin incubus sitting on the stomach of a defenseless, sleeping woman (The Nightmare, 1782) (Figure 1). Vincent Van Gogh believed that “I dream my painting and I paint my dream,” and visions of reverie reached their aesthetic and conceptual heights in the simultaneously beautiful and sinister dreamscapes of the surrealists Salvador Dali, René Magritte, Dorothea Tanning, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Leonora Carrington and Paul Delvaux.

Susan Hiller’s Dream Mapping (1973) involved seven dreamers sleeping for three nights in a field in England, lying within so-called “fairy rings” — a natural phenomenon where a certain genus of mushrooms sprouts up in a large circle. The next morning, each of their dreams was drawn in map form on a piece of transparent paper, and these were sandwiched together into ‘collective dream maps’ for each night. In the 1990s, artist Bruce Gilchrist and programmer Jonny Bradley created DreamEngine software that monitored the real-time EEG data of the brainwave activity of sleeping subjects, and converted it into art. Outputs included 3D plastic sculptural forms; performances where the neural dream activity triggered projections of multiple pre-recorded video clips around a space; and musical notion for a string quartet who sight-read and played the music in real-time.

Dreams inspired many of my creative heroes, including the great literary surrealist George Bataille and theatre visionary Antonin Artaud. “I abandon myself to the fever of dreams,” Artaud wrote, “in search for new laws.” But perhaps most artists are fictive, lucid dreamers who abandon themselves feverishly – communing with other worlds, connecting with the subconscious, drowning in imagery, and reaching out into the ether. As Lucy Powell has noted: “Like a dream, art both is and isn’t true. Both offer a challenge to the tyranny of realism, replacing what is with what might be. Both generate an altered state of consciousness removed from the humdrum – and both lend themselves to interpretation.”

Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) catalysed a fervent dream-fever and new zeitgeist of the psyche as the 19th century turned into the 20th, opening up bold (and contested) new theories of “wish fulfillment” - even our nightmares are our secret wishes, he argued - and the symbolism of the unconscious. Mixing winning ingredients of angst, sex and horror, it was an instant bestseller; Freud later noted that: “insight such as this falls to one’s lot but once in a lifetime.”

Dreams, Angst, Sex and Horror

Dreams, angst, sex and horror have always been prevalent themes in my practice as a multimedia performance artist. In the mid-1970s, I saw a multimedia theatre adaptation of August Strindberg’s A Dream Play by the Welsh theatre company, Moving Being. It stunningly combined live actors with a cinema narrative playing behind them, and it changed my life. I became an experimentalist in multimedia performance, and a researcher into the history of onstage media projections.

Watching A Dream Play, it occurred to me that combining theatre and film could enable a unique form of lucid dreaming where conscious and subconscious could collide and converge. Since then, I’ve worked on projects that explore and enact that fusion in different ways.

There was a period around that time when I could readily induce lucid dreams, although it wasn’t long before I lost the knack. Lucid dreams are all about living the dream, but half here and half there, half asleep, half awake, half you, half someone else. They are willful, directing one’s own experience and fate in the dream world. Lucid dreaming is always on the edge, on the limen, hoping not to awaken, not to fall from the blissful flight taken, from the precipitous edge of the cliff, from the power of being, for that fictive moment, God (or the Devil).

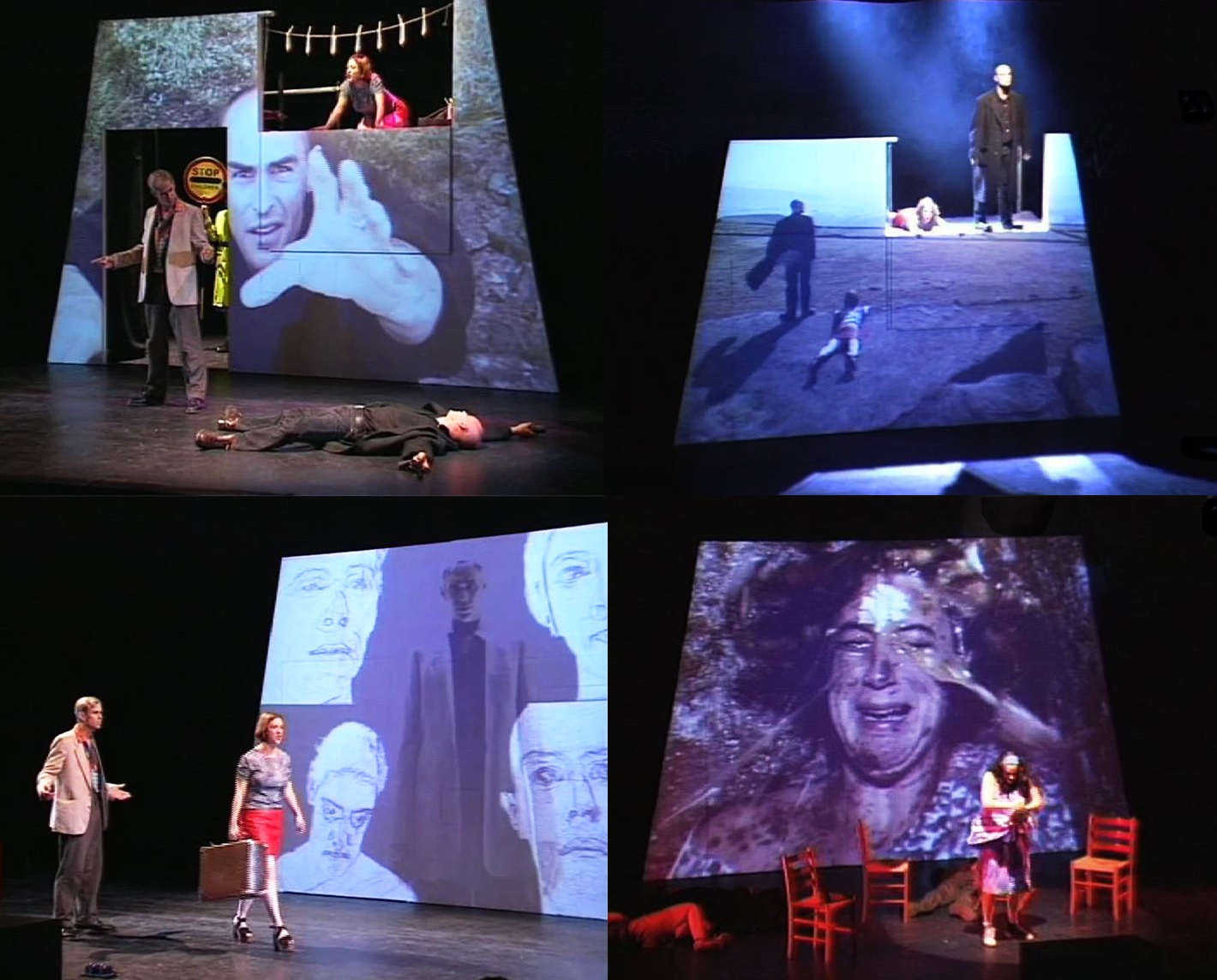

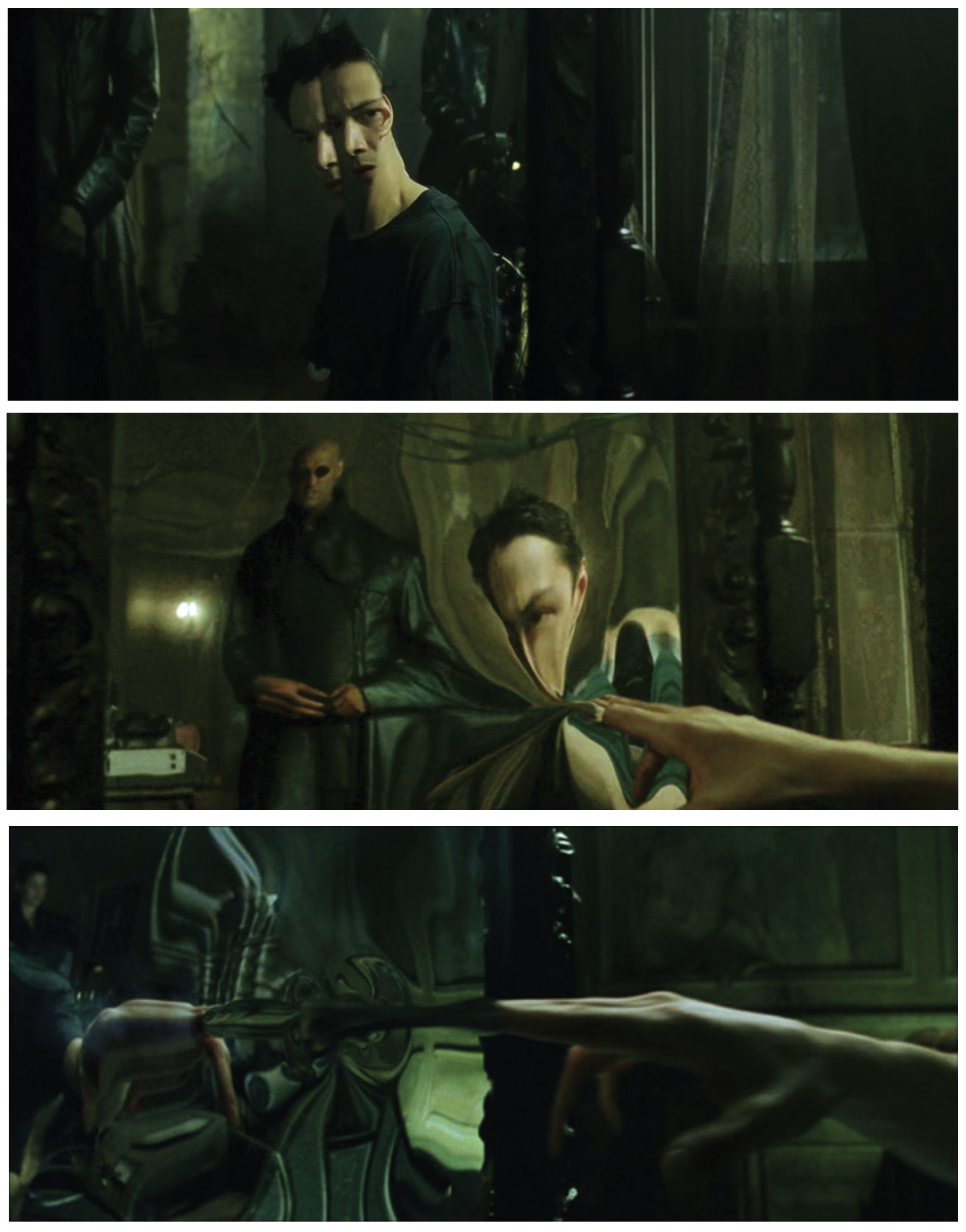

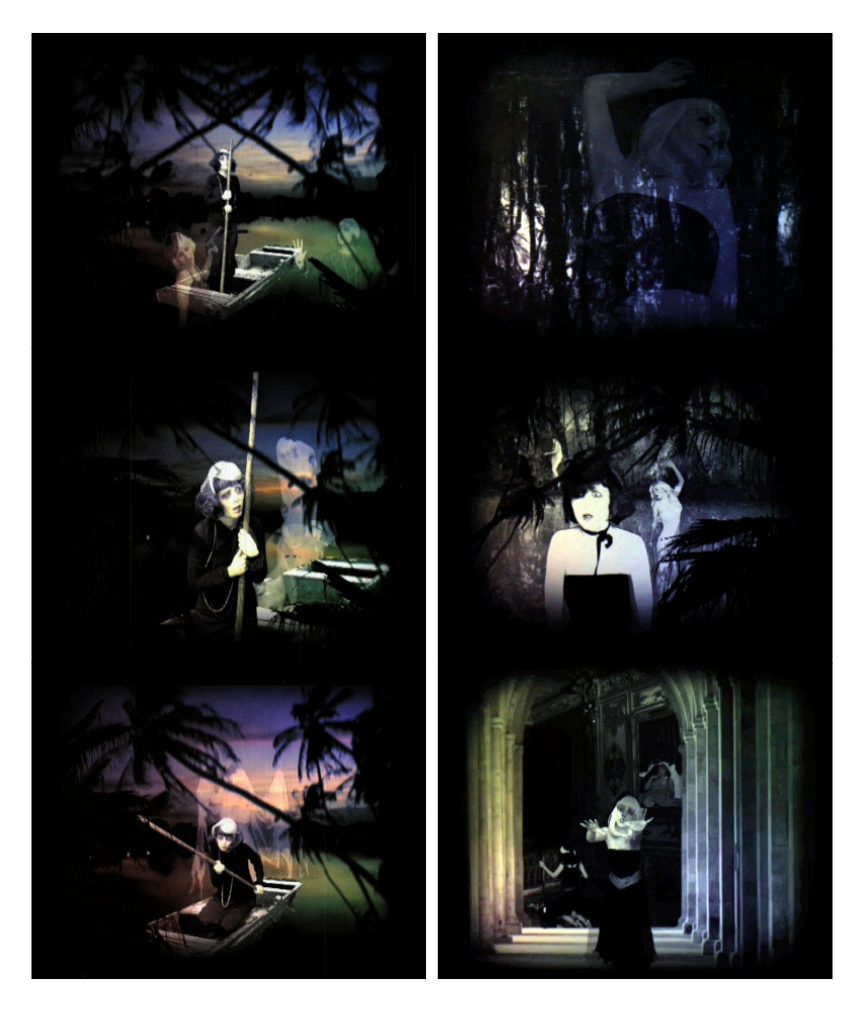

In 1994, I established a multimedia theatre company, The Chameleons Group, to create elaborate lucid dream plays, most recently a one-man interpretation of T.S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land, performed in Chicago, USA in March 2016 (Figure 2). The Chameleons Group performances are presented primarily on theatre stages, but also in gallery settings, and in interactive online environments, such as for Net Congestion (2000), where chat-room audience members were invited to co-write and direct live (streamed) improvised performances in real time (Figure 3). The work generally fuses live performers with projected video imagery – often footage of the same characters, who talk and interact with ‘themselves’ onstage, operating as (invariably darker) doubles, dopplegängers and alter egos, for example, in The Doors of Serenity (2002) (Figure 4).

Figure 2. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, 2013-16

Figure 3. Net Congestion, 2000

As its title suggests, our second production, In Dreamtime (1996), was conceived explicitly as a dream play, and the documenting of each of the four performer’s actual dreams over a three-month period prior to rehearsals served as the core source material for the devising and scripting process. Many video sequences for the show were literal reconstructions, or refined interpretations of the performers’ visions and narratives experienced during sleep. The bottom right image in Figure 4 is one example, where actor Julia Wilson’s dream of being pelted with eggs and blasted by a powerful water-hose was reenacted vividly, while onstage, Wendy Reed simultaneously punches a voodoo doll. The live theatre action for In Dreamtime was played both in front of a four metre-high wooden projection screen, and also ‘inside’ it: the design incorporating four hidden doors and windows, which opened to reveal live action behind, creating an effect of theatre within a movie screen (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The Doors of Serenity, 2002

Figure 5. In Dreamtime, 1996

The show’s narrative revolved around the entanglement of four characters that all experience the same dream. They are manipulated by ‘The Dream Junkie,’ a malevolent spirit hovering between the physical world and the astral plane, who preys upon unwary dreamers. He is ultimately overpowered and killed by one of the rebellious dreamers.

The work has been deeply influenced by the visionary theoretical writings of Antonin Artaud, and my first ever stated research objective was “to update Artaud for the digital age.” In The Theatre and Its Double (1938) – a rare first edition of which I own and cherish, and which emits (at least for me) a spookily powerful aura — he conceives a theatre of cruelty and famously declares that: “actors should be like martyrs burned alive, still signalling through the flames.” Artaud was a key figure within the French Surrealist movement, and was appointed by André Breton as ‘Director of the Surrealist Bureau of Investigations’ in 1925, although they would later quarrel and Artaud would leave the movement, objecting to its increasing politicisation and alignment with communism.

Automatic Dreaming

In The Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), Breton eulogises the surrealist technique of automatism and automatic writing. We have made extensive use of this in the devising and scripting of The Chameleons Group performances, with the resulting material used unabridged, or edited and combined with dialogue created through improvisation. Though its use nowadays is quite rare, we find the automatic writing technique to be highly effective, creating, as Breton has put it: “a considerable assortment of images of a quality such as we should never have been able to obtain in the normal way of writing.” The surrealists essentially inherited automatism from psychics and spiritualist mediums, but as Patrick Waldberg has pointed out, here the message transmitted is sent “not from the spiritual hereafter, but from the actual self hidden by consciousness.”

It is thus akin to dreaming, and in preparation, you empty your mind and put yourself in an open, meditative state, and then start writing as quickly as possible, never pausing for even a millisecond until it’s over. The idea is not to personally write, but as if in a dream to let the unconscious take over, and to spew forth a relentless cascade of words, whatever they may be, without ever interfering or trying to control the stream of consciousness. It is, in Breton’s words: “Thought’s dictation, free from any control by the reason, independent of any aesthetic or moral preoccupation.”

The difference between its use by the surrealists and our methodology is that prior to the writing, the actors go into character and try to allow the character’s subconscious to speak, thus combining surrealist theories of dream and the unconscious with traditional Stanislavskian acting practices. These experiments are thus concerned with the articulation of the unconsciousness of a character, mediated through the unconsciousness of an actor, which is finally ‘made conscious’ in performance.

The results are often startling and dramatic. The writing often has a highly confessional feel, a visual and visceral quality, and conjures images that veer from the visionary to the violent. The scripts frequently contain short and repetitive rhythmical patterns, and are quintessentially ‘dreamlike.’ The In Dreamtime text below by Wendy Reed is a typical example, and was taken verbatim from an automatic writing session, with only the punctuation added later:

Figure 6. Unheimlich, 2005-6

Figure 7. Unheimlich, 2005-6

The Lollipop Lady: I’m not worthy. What is me? There are bruises and I am not worthy. Only of being slashed. Beware of the sheep within. They’re here and you must die. They’re here. The creatures from the shit-pit. The vegetables and deranged minds. The special children. The vandals. The peanut-butter conspiracy revisited. The seeds of discord. The unnatural act. The wrist slashers. The window jumpers. The corpse eaters. Bingo callers. Sheck ‘em up! Giant slugs. Lepers. Keyhole peepers. Die. Die. Die. Die!

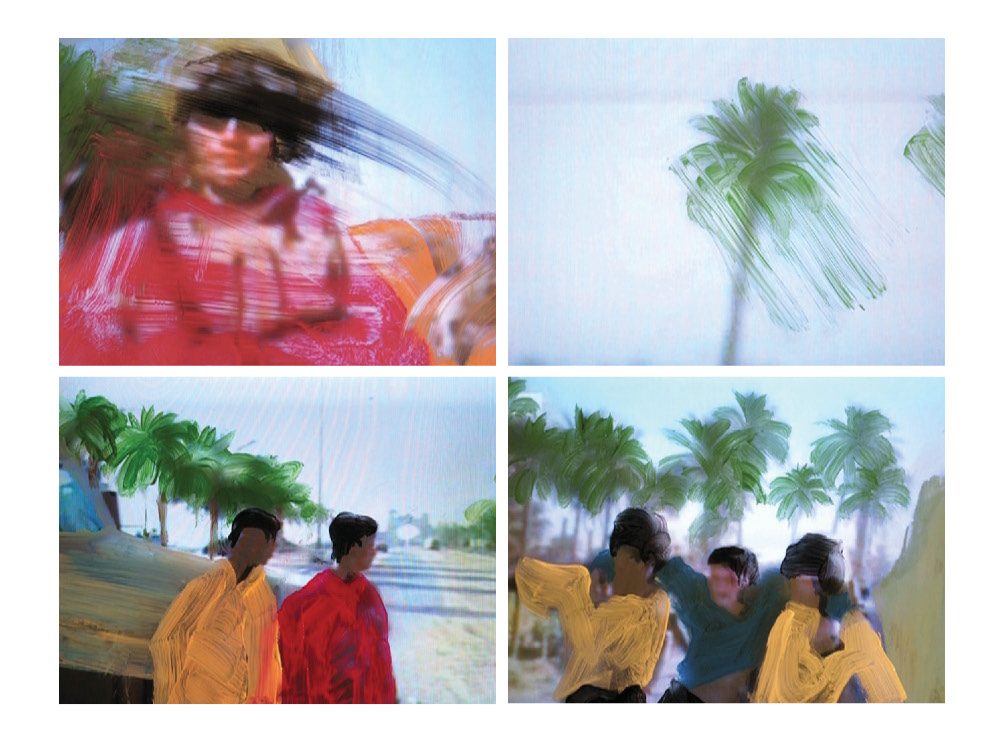

In Unheimlich (2005-6), a collaboration with Paul Sermon, Andrea Zapp and Mathias Fuchs, the dream was ‘extra-lucid.’ Two female Chameleons Group performers worked in a blue-screen space in London and were connected with audience participants in the USA, through a sophisticated videoconferencing system. Using chromakey and video-mixing techniques, on the screens surrounding both spaces, the two sets of participants appeared to be visually conjoined and immersed in virtual backgrounds. They were thus able to see and converse with one another within a shared screen space, to virtually shake hands, and to ‘telematically embrace’ (Figure 6).

These intimate interactions were strange and uncanny (the meaning of the German word Unheimlich, and the title of Freud’s book on the subject), and although they were separated by thousands of miles and several time zones, the telepresence of the bodies ‘on the other side’ was intensely felt, and the sensation of physical closeness and virtual touch was extraordinary. The dramatic interactions between the remote actors and their audiences revolved around fantastical journeys through continually changing background rooms and landscapes, from deserts to polar icecaps, and from 3D game worlds to the fires of hell, with the part-physical, part-virtual mise-en-scène catalysing a vividly ‘telepresent lucid dream’ (Figure 7).

The Mobile Phone as Lucid Dream Machine

Realising the ‘dream of telepresence’ is the most significant cultural development of our age. Distance has collapsed, the so-called real and virtual have converged (or more accurately, the virtual has now been incorporated into the real), and understandings and experiences of presence have been utterly transformed. In my youth, the notion of a videophone conversation was one of the wildest and most alluring of all futuristic science-fiction fantasies. Its Skype and FaceTime reality, indeed ubiquity, today has produced an astounding new form of magic — and we should never forget that ‘digital technologies are a form of magic’ — which we barely give a thought.

The mobile phone has become a ‘lucid dream machine’ where friends and families unite, and where lovers meet, become enchanted and live out their dreams, suspended in space-time, floating together in a different world. ‘Lucid dreams have become synonymous with interactive screens.’

Yet while there may be vibrant interactions and beautiful romances taking place via or within the ‘mobile phone lucid-dream-machine,’ like all forms of magic, it has its darker side. For decades, many of the world’s leading theorists, philosophers and even technologists have been soothsayers warning of the potentially catastrophic social and psychological effects of our willing seduction (or rape) by technology. They include the father of cybernetics Norbert Wiener, who as early as 1954 cautioned that: “We cannot worship the gadget and sacrifice the human being to it”; while a year earlier Martin Heidegger had described human beings as “slaves” already “chained to technology.”

In 1964, Marshall McLuhan emphasised that “technologies are self-amputations”, and later warned of “discarnate” societies detached from reality and therefore any sense of responsibility for it, leaving “whole populations without personal or community values.” In 1981, the most nihilist techno-soothsayer of all, Jean Baudrillard made a pronouncement that “there is no real”; while in the 1990s Paul Virilio was describing a terminal society, and Arthur Kroker offered one of the most searing critiques of all, with a book and title announcing The Possessed Individual (1992). Stephen Hawking has since added his computer-assisted voice to the throng, offering another perspective: “the danger is real that [computer] intelligence will develop and take over the world.”

I fear that our newest dream phenomenon, the mobile phone, which formerly used to simply connect voices, may have since become a dark spectre: ‘a dystopian dream machine for a dysfunctional society.’ The visionary Internet dreams of the 1990s may have transformed abruptly into a 21st century nightmare. In the early 1990s, I was filled with optimism for the brave new digital world; I followed the burgeoning scholarship on the subject avidly, and became one of the most enthusiastic researchers publishing about its influence on the arts and everyday life. But that fervour has waned and I’m tiring of people’s obsessive fumblings with their phone toys — many have become ‘hopeless junkies’ who can’t seem to be able to turn their damned dream machines off.

I fondly recall a dim and distant past (the 20th century) and an idyllic, golden age when people would sit contentedly and simply watch the world go by – and they still do in certain cultures. It was one of the best things you could ever do, since it seemed that you could ‘take the whole world in’ through the microcosm. You were open and available for ‘live interaction’ with whosever passed by, or you could simply stare into space and ‘daydream.’

Today by contrast, whenever there’s an idle moment, there seems instead a dark compulsion to stare at a phone (or any screen will do). It has become a type of Pavlovian conditioning whereby anyone finding himself, for example, sitting alone in public, or simply being somewhere ‘waiting,’ must whip out their phone in a trice and gaze moronically at it. Sometimes, of course, it’s to view or communicate something important. But more often – and I suspect first-and-foremost – it’s as a default ‘defence mechanism’ to instantaneously shield us from the quotidian world. Phones may have become dream machines, but they are robbing us of daydreams. Most often, phone dreams are dull distractions from direct thought or action, they’re rarely visionary, and are generally banal. That the whole of human life and experience has started to migrate inexorably into a metallic lump of circuits is deeply saddening.

The phenomenon seems particularly strong here in Southeast Asia, where the old opium pipe dreams have transformed into a new form of mirage … and dependency. We live in an increasingly somnambulant society, where the opiate hallucinations of the region’s past have turned into a craved addiction for the ghostly, ephemeral apparitions of social media.

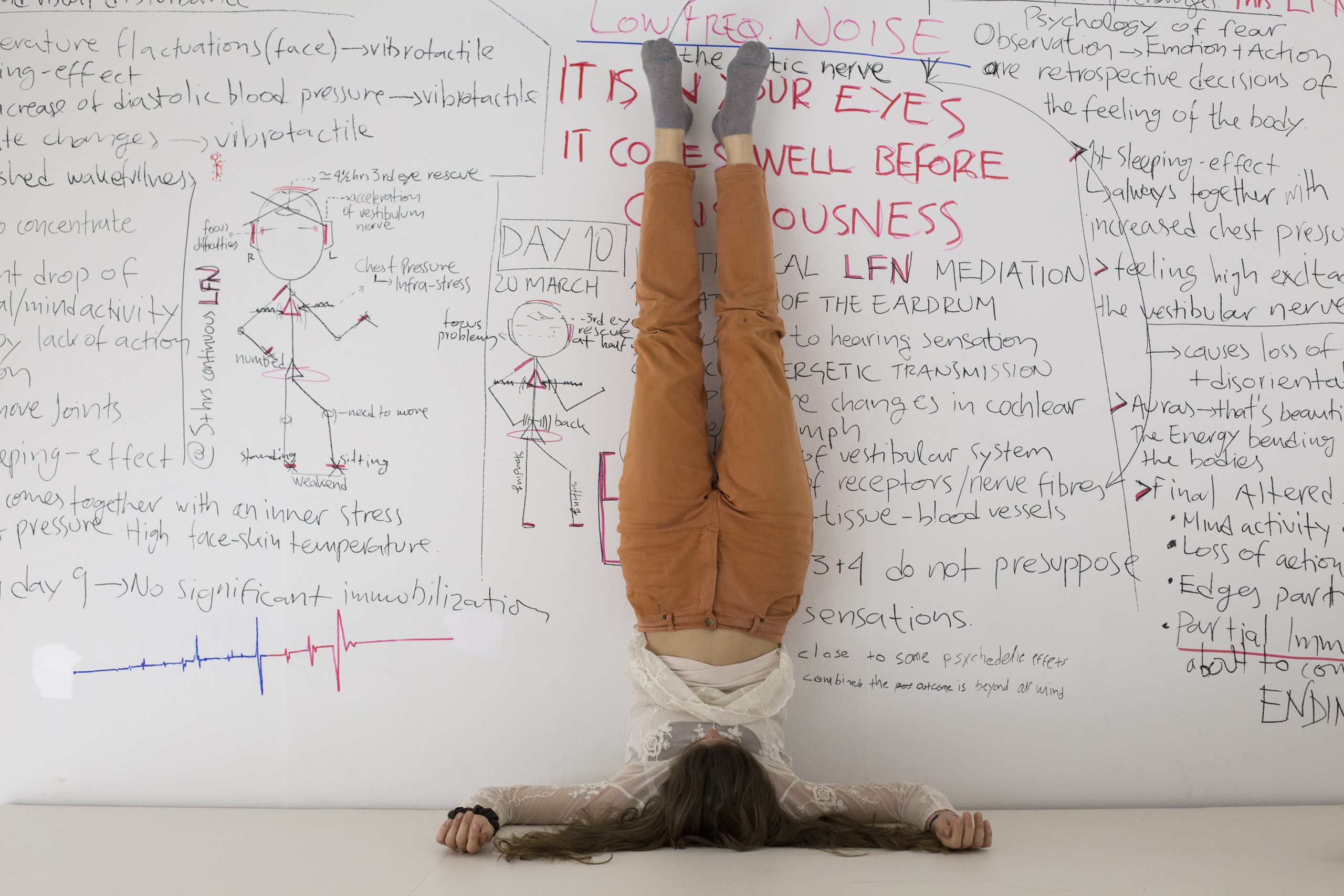

I snapped a photo the other day, which I’ve entitled: The Answer is Action: but not often when you’re lost in your dream machine … (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The Answer is Action, 2016

Dreams, Clichés and Visionary Theatre

There are many potent clichés about dreams, and the best one of all is that ‘they can come true.’ Occasionally they do. The ideology of the ‘American Dream’ is that if you are determined enough, hardworking enough – and perhaps also, selfish and ruthless enough – you can succeed ‘beyond your wildest dreams.’ And when you’ve made it, when you’re at the top, you can ‘live the dream.’ Marilyn Monroe once said that there must be thousands of girls like her sitting in their rooms, dreaming of being a movie star, but she was dreaming the hardest.

Theatre and opera director Robert Wilson has also dreamt hard to become one of the great auteurs of dreamscapes. His stage works are exercises in dazzling design, incandescent light and devastating images; he is one of the art world’s most original and mercurial fictive dreamers.

Theatre comprises many things, but perhaps most fundamentally bodies, space, light and time. Wilson does mesmerising things with each and every one of these. The performers’ movements are stylised and heightened in such a way that apparent minimalism becomes maximalism; and his command of space and light, (his first degree was architecture), is breathtaking. When these elements are combined with an unnerving manipulation of theatrical time, the effect is ‘real yet unreal, and utterly dreamlike,’ as in his productions of Peter Pan (2013) and Pushkin’s Fairy Tales (2015) (Figures 10 and 11).

In some of his productions, figures cross the stage with the millimetre-by-millimetre momentum of a glacier. His mischievous playing with time, slowing it, elongating and seemingly extruding it is exquisite, but also so excruciating that it hurts. No one in the history of theatre has brought the notion of time, tempo and temporality so much to the fore; and this is doubled through his trademark use of repetition.

Physical gestures, musical phrases, and pieces of text are repeated over and over again. In I WAS SITTING ON MY PATIO THIS GUY APPEARED I THOUGHT I WAS HALLUCINATING (1977), the second act is an exact repetition of the first, but the monologue is performed by a female actor (Lucinda Childs) whereas the first was performed by a man (Wilson himself). At one level it is ridiculous, illogical. But on another it is inspired, and its braveness and vision produces a mesmeric effect, a truly uncanny dream. As the philosopher Gilles Deleuze has written: “There is a paradox that something truly NEW can only emerge through repetition.”

Dreams are endless repetitions of our own, and the collective, subconscious. Like art, they embody and enact personal and universal hopes and fears, and conjure visions of angels and demons, darkness and light. All dreams are fictive dreams, and all dreams are real. We freeze time and traverse space. We dream alone, yet we all dream together. As we do so, taking Robert Wilson as our lead, let’s try to dream more beautifully and lucidly.

As Jorge Luis Borges asked: “Who will you be tonight in your dreamfall into the dark?”

Figure 9. Robert Wilson’s Peter Pan, 2013. Photograph © Lucie Jansch

Figure 10. Robert Wilson’s Pushkin’s Fairy Tales, 2015. Photograph © Lucie

Essays

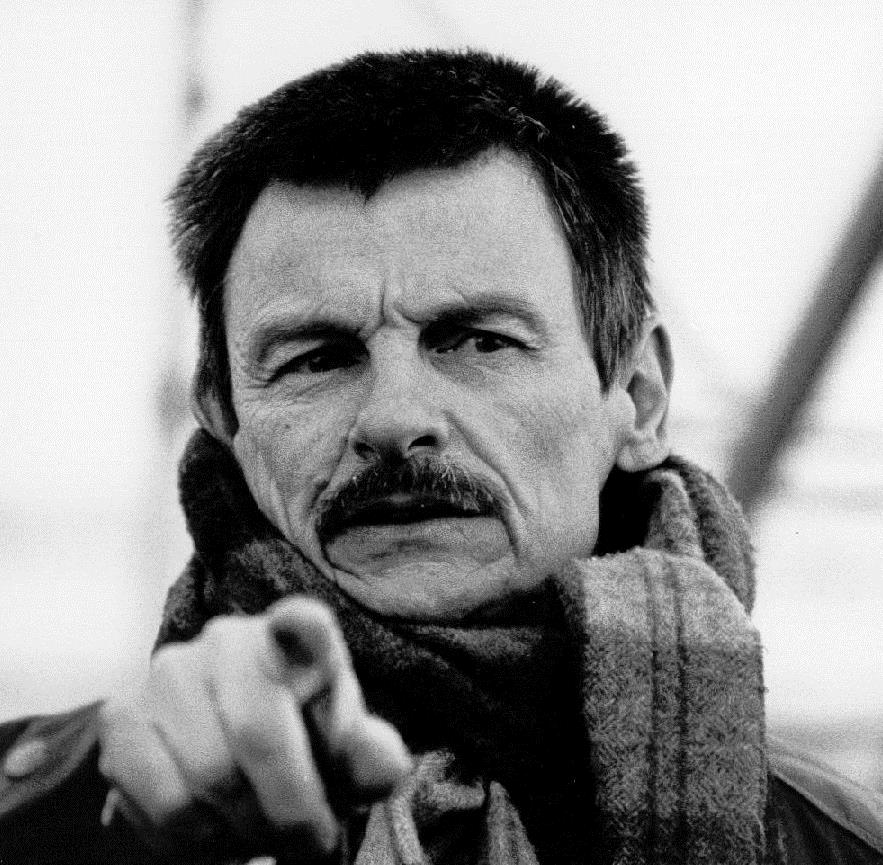

Ai Weiwei at media conference National Gallery of Victoria, Australia, November 2015. © Peter Hill.

AI WEIWEI

Ai Weiwei is one of several artists whose work only connects tangentially with the art of the Superfiction. However, like Jorg Immendorff, Group Irwin, and other Heroic Amateur artists, much of his work grows from a political-conceptual background. The Duchampian art object (in Ai Weiwei’s case) subverts dogma through poetic fiction. See profile at superfictions.com

FRANCIS ALŸS

Francis Alÿs uses many Situationist devices of walking, thinking, and doubting, which parallel Superfiction strategies. He exhibited at the 2007 Munster Sculpture Project and has been involved in projects and publications in New York, London and Mexico. Postmedia provides this brief biography:

“Francis Alÿs was born in 1959 in Antwerp, Belgium, and currently lives in Mexico City. His projects include Paradox of Praxis (1997), for which the artist pushed a block of ice through the streets of Mexico City until it melted, and, most recently, When Faith Moves Mountains (2002), in which 500 people at Ventanilla, outside Lima, Peru, formed a single line at the foot of a giant sand dune and moved it four inches using shovels.”

For more recent projects see Wikipedia.

THE AFTER SEX CIGARETTE

See THE ART FAIR MURDERS AND THIRTEEN MONTHS IN 1989

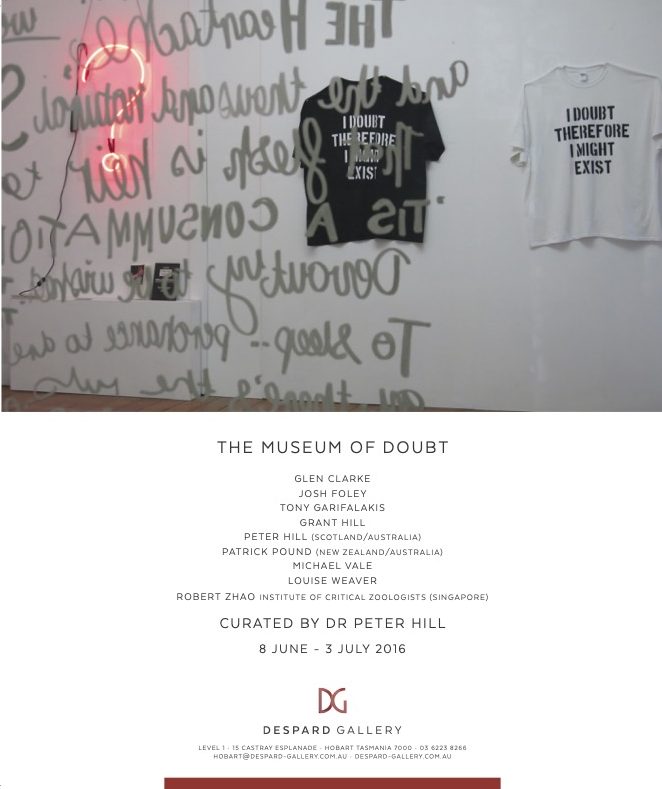

Advertisement for The Museum of Doubt exhibition, Despard Gallery, Hobart,

Tasmania, Australia, June 2016. © Peter Hill and Despard Gallery.

THE ART FAIR MURDERS

An on-going Superfiction created by Peter Hill in 1995 in Hobart, Tasmania. It is part installation, part novel, and part website. It is set in 1989, the great year of revolutions and world events: Tiananmen Square, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the execution of the Ceaușescu, the release of the Guildford Four. Its structure revolves around Twelve Chapters, Twelve Months, Twelve Murders, and Twelve Cities. It took three contemporary clichés – the serial killer in popular fiction; the overuse of the mannequin in installation art; and the widespread use of the colour orange in the advertising industry. It speculates on what would happen if a serial killer was loose in the art world, killing one art world personality at each of twelve art fairs around the world. The structure of the novel/installation follows the real world diary of international art fairs: January, Miami; February, Madrid; March, Frankfurt; April, London; May, Chicago; June, Basel; and so on though to November, Cologne; and December, Los Angeles.

The viewpoint of the narrative is further complicated by the fact that the novel is supposedly being written by Jacko, a taxi driver in Aberdeen, Scotland. Jacko is an ex-art transporter who was sacked when a small Lucian Freud went missing on a trip to Berlin. He had originally trained at Goldsmiths, three years ahead of the group that would become known as the yBas (young British artists). While waiting in his cab for fares, Jacko passes the time writing The Art Fair Murders.

Peter Hill has built “Chapters” of this Superfiction in galleries and museums around the world, including Auckland City Gallery, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, Biennale of Sydney (2002) in MCA, Incinerator Gallery, Melbourne (See AUTHENTICITY…?), Hubert Winter projects, Vienna.

See www.superfictions.com/theartfairmurders

AUTHENTICITY...?

Opened on 1st April, 2016 (the holy day of Superfictions) Authenticity…?, at Incinerator gallery, Moonee Ponds, was curated by Richard Ennis and built on an earlier exhibition, see SUPERFICTIONS 2: as if, at King’s ARI, Melbourne in 2014. Writing in Art Guide Australia (May/June 2016), Natalie Thomas said: “Darren Sylvester, Jacqui Shelton, Michael Vale, Patrick Pound, Peter Hill and the DAMP Collective are presently taking some time off from the responsibilities of reality. Instead, these artists seek refuge in the magical mystery of make-believe. They use a range of strategies including humour, satire, mischief and fakery to question the ways authenticity functions within the art world and within the broader cultural landscape.”

In Authenticity…? these tricksters ask a range of questions, like what does an authentic artwork look like, and what does the artist who produced, say authentic artwork look like? In this exhibition, curator Richard Ennis has brought together a group of artists interested in the authentic versus the inauthentic.

Take Melbourne-based artist group DAMP for instance. DAMP has had more members than Mark E. Smith’s UK band, The Fall. The revolving door of group membership often illustrates the difficulties of collaboration. When viewing the shared artistic outcomes of a group of individual artists, it’s interesting to ponder what has played out behind studio doors to complete a project. Whose ideas have presented the strongest in the combined work, and are we actually seeing a collaboration at all?

Patrick Pound doesn’t even make his own art and yet, he’s a much-in-demand artist, his career the envy of many. A productive day at the studio for Pound might entail buying up collections of old photos off eBay and reclassifying the bounty into poetic subgroups. His sleight of hand is so slight you have to look extra hard to even see its trace. Of his practice, Patrick Pound says: “Photography is the medium of evidence, but we are never exactly sure of what exactly. Truth is a little overrated if you ask me. But I wouldn’t.”

To add, from the catalogue to Authenticity…?:

“Darren Sylvester presents a 27-minute, sitcom length, video self-portrait titled Me, 2013. Sylvester casts 16 different actors as modern day Adam and Eve style characters, to speak for and about him. The actors, both a male and a female Darren, contemplate the world through that old world performance, conversation. They talk about life through Facebook, Twitter, music, The Simpsons, Tupac, the death of MySpace, the death of Friendster, Sarah Silverman, the decision about having kids or not and how we all feel like we’re a failure in the eyes of our parents.”

“Peter Hill is well known for his Museum of Contemporary Ideas and his Superfictions which function both as artworks and as a testing ground for ideas. The conceptual framework of the works is more important than what the art is made from. Meaning is given precedence over form. Like the other artists within this exhibition, you’re not exactly sure what is being sincerely communicated through their art and what is a falsity. Surely an artist wouldn’t tell you a lie and keep a straight face, would they?”

BANALISTS

See SITUATIONISTS AND REALPH RUMNEY

BLAIR WITCH PROJECT

The Blair Witch Project was one of the first mainstream Superfictions in which the film’s directors and producers created a superfiction that played with the emotions of both cast and cinema audience. See Orson Welles’ The War of the Worlds.

A. A. BRONSON

A. A. Bronson describes himself as being “one of the three member group General Idea between 1969 and 1994.” He is the last surviving member. A biography of General Idea can be found at: http://www.aabronson.com/art/gi.org/biography/biointro.htm

The following interview with A. A. Bronson was made by Peter Hill at the Basel Art Fair in June 1993:

Paintforum International: Making Superfictions Real, by Peter Hill, Blindside Gallery, Melbourne, Australia (2015). © Peter Hill.

Peter Hill: General Idea is a fictional construct that finds its subversive outlets across a range of media including film, performance, installation, video and photography. It is 24 years since the three of you invented it. How close have you remained to your original vision?

A. A. Bronson: I don’t think there was anything we would call an original vision as such back in 1968, and we didn’t actually use the name General Idea until 1970 when we used it for a particular project. Later we established a programme for ourselves that would last us until 1984. When that date came around we had to decide whether we would continue to work together or whether we would stop. Our original intention was to close the project in 1984.

For the complete interview visit: www.superfictions.com

CAMERON OIL

A fictitious oil company created by Peter Hill in 1989. Within the fiction, Alice and Abner “Bucky” Cameron made their billions from the Cameron oil fields in Alaska. They bankrolled New York’s Museum of Contemporary Ideas on Park Avenue and their huge egos are loosely modelled on the Paul Gettys and Armand Hammers of this world. In the early 1990s, Cameron Oil began a new life on the newly available internet.

JANET CARDIFF

Janet Cardiff has, amongst many other projects, made a détournement of the Situationist derive and melded it with film noir and pulp fiction. She first came to international attention with her work at the Whitechapel Library, London, Case Study B, in which ‘spectators’ became ‘participants’, and were sent out into the streets of London with headphones and a CD that gave instructions on where to walk – across busy streets and down dark lanes. An audio equivalent of trompe l’oeil was explored when the noise of screeching traffic on the headphones merged with real traffic noises on the street. Much of her work has been made in collaboration with George Bures Miller. She has constructed ‘walks’ in many parts of the world which often have powerful touristic backdrops such as the Sydney Opera House and the Egyptian Pyramids.

GARY CARSLEY

Gary Carsley’s work creates a Superfiction from a range of cultural and technical tropes including post-colonial history, industrial production methods, and the idea of the “draguerrotype.” In 2009, when Peter Hill asked him about his recent project for the Singapore Biennale, curated by Fumio Nanjo, and his subversion of IKEA flatpacks into works of art, he said:

“I had been looking for a way to critically re-engage with the conceptually playful positions of the early 1960s. It was a radical moment, full of radicalising potential and IKEA’s flat pack is similarly idealistic, particularly in the way in which it co-opts the spectator in a form of expanded, collaborative authorship similar to the way FLUXUS artists like Yoko Ono were then doing.”

DAMP

Writing about DAMP in Photofile 59, in a section called ‘Encyclopaedia of Photofictions,’ Peter Hill described some of their projects up to 2000:

“DAMP: A collaborative art group based in Melbourne. They have been working together since 1995. They meet once a week in twelve-week blocks, usually in the TCB studios in Port Phillip Arcade. Established with Geoff Lowe, DAMP has developed into an independent collective with an extensive membership. Their work seems to work simultaneously with and against the media in a similar way to the UK’s latest tabloid art stars The Leeds 13. Peter Timms gave a good introduction to their work in The Age, Wednesday 18 August, 1999, when he wrote: “Apparently things got a bit out of hand at 200 Gertrude Street a week or so back. During an exhibition opening, when the gallery was packed with people, a young couple started arguing. It was unpleasant, but at first didn’t cause too much disruption, apart from the odd disapproving look. Then the dispute got louder and more insistent and one or two others became involved. A young man had a glass of wine thrown in his face, then the shoving started. Glasses and bottles were knocked over and smashed, and a girl was pushed through the wall. The installation work in the front gallery, by a group of artists calling themselves DAMP, was almost completely wrecked. Only gradually did people start to realise that DAMP’s installation was not being destroyed but created.”

JACQUELINE DRINKALL

Jacqueline Drinkall works across a range of conceptual and installation art, some of which grew from her time when she worked as an assistant to Marina Abramović, others growing from her investigations into art and telepathy. The project which came closest to a Superfiction involved employing the services of a psychic, at Sydney’s Circular Quay and instructing him to contact the spirit of Marcel Duchamp. The outcome of this meeting of minds was a series of drawings made by Duchamp channeled through the Australian medium.

IAN HAMILTON FINLAY

Ian Hamilton Finlays’ creation of The Saint Juste Vigilantes (a “real” Superfiction) and his battles with both the Hamilton Rates authorities and the French government were explored in an interview with Peter Hill in Studio International, No 1004, 1983 (London):

Peter Hill: Before we speak about the problems you have had to face over the past year or so it might be worth speaking about the philosophy behind your garden temple at Little Sparta. As one of the most beautiful collaborations between man and nature that I have ever seen, I wonder how it all began?

Ian Hamilton Finlay: Every question can be answered on different levels, or, that is, has a number of different answers. As a building the garden temple began as a cow byre which we converted into a gallery and then, over a period, into a garden temple, or as we at first described it ‘Canova-type temple’ – referring to the temple built by the Italian neo-classicist. This was not to equate our garden temple with Canova’s temple but to explain it by means of a precedent: a building which housed works of art but which did not present itself specifically as an ‘art gallery’. But in another way one could say that our garden temple began because we had a garden, and we have a garden because we were given a semi-derelict cottage surrounded by an area of wild moorland. This moorland represented a possibility, and produced our response. (I say ‘our’ to include Sue Finlay who has been, from the beginning, my collaborator on the garden).

For complete interview visit: www.superfictions.com

JOAN FONTCUBERTA AND PERE FORMIGUERA

Using taxidermy and sepia photography, these Catalan artists created the supposed zoological discoveries of Dr. Peter Ameisenhaufen who died in a car crash north of Scotland. Joan Fontcuberta has since gone on to create numerous superfictions, usually photographically and through analogue and digital techniques.

CHRIS CHONG CHAN FUI

Malaysian artist, Chris Chong Chan Fui, created BOTANIC (2013) which comprises eight large digital prints on paper (each 152 x 213cm). According to the catalogue of the 2013 Singapore Biennale: “Malaysian artist, Chris Chong is most commonly known for his work in film, but his most recent work and Singapore Biennale 2013 contribution, BOTANIC, is a series of drawings. These drawings follow the style of traditional botanical illustrations, an approach that is still used today to capture the image of a plant for scientific purposes. Botanical illustrations are traditionally made from observation of natural flowers, where the form, colour and details of the plant are rendered in great detail for referencing and understanding plant species. However, Chong’s illustrations, while depicting similar qualities, are derived from artificial flowers instead. At first, a viewer might not realise that the images are based on non-living plants, but closer looking will reveal unnatural textures and shapes to the array of plants illustrated. As an artist who commonly makes use of digital media, Chong’s process of hand drawing demonstrates a return to a more basic form of art making as he focuses upon observational drawing. These drawings are a reflection of the artificiality that is often found in contemporary culture today. The artist is critical of the fact that such artificiality is so widely accepted as a replacement for nature. Hence, he uses his drawings of artificial plants to capture an example of a commonplace substitute.”

RODNEY GLICK

An Australian artist based in Perth (WA), Glick has created many Superfictions, notably “the Glick International Collection” and the work of the philosopher Klaus. Klaus had a ten-step programme for reaching enlightenment and every year Klaus would announce the next step. Eventually he was due to disclose the 10th step at the United Nations in New York, but failed to appear at the appointed hour. Several weeks later, Glick was found by a gardener wandering in a garden in Bethlehem. Glick revealed the 10th step to the gardener, which was “Start again”.

RICHARD GRAYSON

Richard Grayson is an artist, curator, writer, and director of the 2002 Biennale of Sydney, (The World May Be) Fantastic. Many of the artists included in this event created work that could be described as Superfictions. In the introduction, he writes: “The traffic between ‘the real’ and the ‘not real’ is of course osmotic. Sir John Manderville published Manderville’s Travels at the end of the 14th century. To us, it is a work of fiction and fable, with its reports of one-eyed people in the Andaman Islands and dog-headed people in the Nicobar Islands – Manderville also locates paradise, but rather charmingly says he cannot say any more about it as he has not yet been there. Certainly by the 16th century ‘to Manderville’ had become a colloquialism for lying and exaggerating. However Columbus planned his 1492 expedition after reading the book, Raleigh pronounced every word true, and Frobisher was reading it as he trail blazed the northwest passage. So the ‘false’ maps gradually segue into the maps we now accept, but these too are open to constant revision.”

See also ALEKSANDRA MIR, SUZANNE TREISTER, JANET CARDIFF AND PETER HILL

GUILDFOR PUB BOMBINGS

The release of the Guildford Four in 1989 after 14 years of wrongful imprisonment was instigated by revelations of acts of fabrication by the police, as complex as any Superfiction. For one of the best overviews of this case see Ronan Bennett’s lengthy article in The London Review of Books, 24th June, 1993.

IRIS HÄUSSLER

One of Iris Häussler’s best-known projects, The Legacy of Joseph Wagenbach, begins with a series of “views” expressed by, in turn: “the visitor”; “the archivist”; “the protagonist”; “the artist,” and “the curator.” The first of these begins: “We left the Field Office to walk towards Wagenbach’s house, wearing white lab coats. The archivist knocked on the door before turning her key. We squeezed inside. Stale air. Dim light. Shapes formed in corners and shadows that I would have never imagined [...]” while the last one reads: “Approximately two years ago [...] Iris told me about an idea for a work titled The House of the Artist; however she had not yet developed it due to the scale, intensity and logistics of the project. [...] Basically that was it, a single idea of immense proportions. I immediately knew we had to make this happen and that it would be an extremely significant project.”

AMANDA HENG

In 2006, Amanda Heng created a fictitious travel agency that promoted a tour of four Chinese-Singaporean cultural collections that were notionally re-sited in the region, outside Singapore. The artwork, Worthy Tour Co (S) Pte Ltd, was first shown at the inaugural Singapore Biennale (City Hall building). This artwork has been recreated within the new National Gallery Singapore, halfway up the wide internal flight of stone stairs. According to the wall text: “These collections reveal the cultural intersections between Singapore and the rest of Asia, and also considers the place of these cultural materials within museology.” There are interesting parallels between this project and Urich Lau’s The End of Art Report (2013) exhibited at the 2013 Singapore Biennal

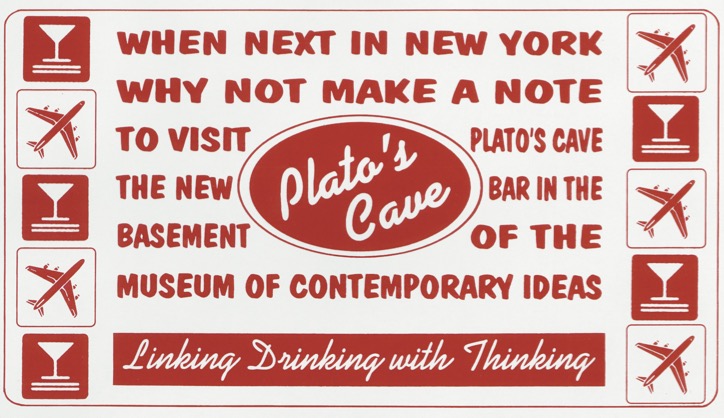

Plato’s Cave: Linking Drinking With Thinking, the bar in the basement of

The Museum of Contemporary Ideas (1989 – continuing). © Peter Hill, 1989.

PETER HILL

Peter Hill is a Glasgow-born Australian with dual nationality. In 1989, he launched New York’s Museum of Contemporary Ideas, supposedly the world’s biggest new museum and the first of many Superfictions he created (see The Art Fair Murders). Hill originally coined the term to describe the work of a number of artists operating independently in the late 1980s. These include Res Ingold (Switzerland) and his fictitious airline; SERVAAS (Netherlands) and his fictive world of deep sea herring fishing; the Seymour Likely Group (Netherlands); David Wilson’s Museum of Jurassic Technology (USA); Rodney Glick’s (Australia) theories of Klausian Philosophy; and Joan Fontcuberta’s and Pere Formiguera’s (Spain) creation of the German zoologist Dr. Peter Ameisenhaufen.

Since 1989, Peter Hill has gone on to create his Encyclopaedia of Superfictions which documents many more Superfictions artists and art groups, most recently The Bruce High Quality Foundation University (BHQFU) based at Cooper Union, New York (see Art in America, March 2010, pp59-64), and numerous Singaporean artists including Amanda Heng, Adeline Kueh, Urich Lau, and Robert Zhao.

When Peter Hill’s first Press Release for the Museum of Contemporary Ideas was mailed out in 1989 to newspapers, news agencies (Reuters/Associated Press), art magazines, critics, and artist friends, the German magazine Wolkenzratzer (Skyscraper), edited by Dr. Wolfgang Max Faust, believed it to be real and printed a story about the generosity of its benefactors Alice and Abner “Bucky” Cameron who made their billions from the Cameron Oil fields in Alaska. The article was written by Gabriela Knapstein (now curator at Berlin’s Hamburger Banhof), and as a result Wolfgang Max Faust was asked to chair a meeting of German industrialists and curators to see if Frankfurt could build a museum based on the model of Hill’s Museum of Contemporary Ideas.

See www.superfictions.com for complete Encyclopaedia, artist interviews, and exegesis of Peter Hill’s studio-based PhD on “Superfictions.”

PIERRE HUYGHE

Pierre Huyghe was born in 1962 and trained at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs. In 2001 Huyghe represented France at the Venice Biennale, where his pavilion, entitled Le Château de Turing, won a special prize from the jury. In 2002 Huyghe won the Hugo Boss Prize from the Guggenheim Museum, and exhibited several works there the following year. In 2006, Huyghe’s film A Journey That Wasn’t was exhibited at the Whitney Biennial in New York, and at the re-opening of ARC/MAM and Tate Modern. He is represented by the Marian Goodman Gallery.

The following is a description of the work Huyghe made for the 2008 Biennale of Sydney, directed by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, director of the 2012 documenta:

“At the Sydney Opera House a unique experience occurs throughout the course of a day and a night. An event with no beginning and no end, no division between stage and public, no specified path to take – it is a theatre liberated from rules. From the stalls to the circles to the stage, a forest of trees has grown and spread throughout the entire Concert Hall. The light of dawn barely shines on this valley obscured by clouds. This is an in-between reality, an image of an environment, a fact that appears for a brief moment just before vanishing.”

RES INGOLD

Ingold Airlines is the fictional creation of Res Ingold. His early work appeared only in business plans. And like the advertisements of SERVAAS and the press releases of Peter Hill, the work used only “spot colour” to sustain the illusion and to keep production costs to a minimum. Ingold logos appeared on executive jets flying in to Documenta 1X in Kassel. Through fiction he predated (in 1989) many innovations in 21st century intercontinental flight such as the use of gymnasiums and cocktail bars on long-haul flights.

INSTITUTE OF CRITICAL ZOOLOGISTS

See ROBERT ZHAO

INSTITUTE OF MILITRONICS AND ADVANCED TIME INTERVENTIONALITY

See SUZANNE TREISTER

ADELINE KUEH

See LULU

URICH LAU

In his installation The End of Art Report (2013) with three single-channel videos (duration 1:30 mins each), Malaysian-born Urich Lau (based in Singapore) asks the question: “When art is in the news, how does the media influence and inform our perception of it? Can I influence the perception that viewers have of art when it is coming through the media?”

To make this work, he persuaded former news reader Duncan Watt to deliver fictitious news reports about the closure of three of Singapore’s leading museums: National Art Gallery, Singapore, Singapore Art Museum (in which his installation was placed during the 2013 Singapore Biennale), and National Museum of Singapore. According to the Biennale catalogue, “The End of Art Report seeks to raise the awareness of Singaporeans about the possibility of the loss of national cultural institutions, so as to create a debate over the need to ensure the long-term viability of these institutions beyond being instruments of economic value. In recent years, independent art spaces in Singapore such as Plastique Kinetic Worms (1998-2008), p-10 (2004-2007) and Post-Museum (2007-20011) had to give up their spaces due to rising rents and the pressure of maintaining the premises and running programmes with limited resources. Will the national cultural institutions face a similar fate when resources become limited? Following Marxist theory, are cultural institutions in Singapore merely the superstructure to the economic base?...The public responses to the fictional news reports could range from those who believe in the veracity of the reports to those who are either skeptical or do not believe in it.”

THE LEEDS 13

“The Leeds 13 first gained notoriety when they leaked to the British tabloid newspapers that they were using university money to go on holiday to Spain. In fact, the 13 art students from Leeds University stayed in hiding for a week, spent none of the money and fabricated holiday photos on a nearby beach in Scarborough. A few weeks ago the Leeds 13 presented their final degree show, made up entirely of work by other artists, ranging from Rodin and Damien Hirst to Marcel Duchamp. How do university degree examiners assess such a submission? Should it get a first or a third? It is not the first time such problems have arisen. Not so long ago, identical twins Jane and Louise Wilson submitted identical projects at different art schools in the UK. They are now candidates for the 1999 Turner prize. The Leeds 13 is just the latest batch of artists to create a superfiction that plays with the media and with the viewer’s ability to correctly read visual material. It goes beyond the notion of a “hoax.” Instead it illuminates, to paraphrase Picasso, how “art is a lie that can reveal the truth.””

From an article by Peter Hill in the Times Higher Education Supplement London, 6th August, 1999. Google: Superfictions

Adeline Kueh, Love Hotel (Installation view in What it is about when it is about nothing at Mizuma Gallery, Singapore),

LED Lights, aluminium, acrylic, sex appeal, Dimensions Variable, 2015. Photo courtesy of Tan Hai Han.

LULU

“Lulu” is the alter ego of Singapore-based artist Adeline Kueh. Through Lulu, Kueh explores the projected sexuality of an Asian woman. In Love Hotel, Lulu appears within the series of videos, photographs, installations & durational performances that take on the complexity of our desire for connection in an age of contemporary urban living. Having failed as a movie star, Lulu now runs a Love Hotel for a living. With En passant, Lulu’s chance encounters in transitory spaces are manifested. By looking at the gamut of emotions and issues surrounding our relationships to the city, acquaintances and even strangers, the works question experiences of isolation in the search for love as well as our expectations of what makes up these liminal spaces of intimacy.

MADE IN PALESTINE MADE IN ISRAEL

A fictitous team of artists created by Peter Hill as part of his ongoing Superfiction The Art Fair Murders. One artist is Israeli, the other Palestinian, though neither ever reveals his or her true name. For over 30 years they have been photographing artists and curators around the world at events such as The Venice Biennale, documenta, the Munster Sculpture Project, and the Sydney Biennale. Double portraits are then produced under the name, “Art World Fan Club,” with one portrait designated “Made in Palestine” and the other, “Made in Israel.” Peter Hill originally decided which artist would represent “Palestine” or “Israel” by the throw of a dice (see THE DICE MAN) – but now he invites the real artist to throw the dice. These works can appear in various scales from postcards to billboards. Artists so far included: Martin Creed; Marina Abramović; Dennis Hopper; Martin Kippenberger; Joseph Kosuth; Hermann Nitsch; The Ramingining Artists and Burial Poles; James Lee Byars; John Armleder and Sylvie Fleury; Res Ingold, Callum Innes, Fumio Nanjo, and Heri Dono.

This project grew from the post-traumatic stress Peter Hill experienced after witnessing the Guildford Pub Bombings (1974). In the aftermath of the trauma he experienced, he reduced his agnostic response to “No Idea Is More Important Than A Human Life.” Hill has since sent hundreds of ‘Made in Palestine, Made in Israel’ postcards to world leaders, religious leaders, journalists, and social commentators, with this phrase scrawled across the back of the card. Sometimes, alternative phrases are used, including “STOP THE KILLING NOW,” and “You Lied, You Said There Would Be A Ceasefire.”

ERN MALLEY

The Ern Malley hoax, which Peter Hill sees more as a Superfiction than a hoax, has parallels with the fictive Scottish poet ‘Ossian,’ created by James Macpherson who supposedly discovered him in ancient Gaelic texts. For those wishing to read about these ‘real’ poems by a fictitious poet (Ern Malley), the best starting place is Michael Heyward’s book on the subject.

ALEKSANDRA MIR

For profile and interview with Aleksandra Mir in THE BELIEVER, San Francisco, December ’03 / January ’04 see www.superfictions.com/encyclopaediaofsuperfictions.

MISS GENERAL IDEA

See A.A. BRONSON

MONA (MUSEUM OF OLD AND NEW ART)

The creation of polymath and multi-millionaire gambler David Walsh (whom Peter Hill describes as “an artist who choreographs the work of other artists. Who thinks and acts like an artist”), Mona is perhaps the world’s most astonishing museum. It is situated just outside Hobart, the capital of Tasmania, Australia’s island state. In 2011, Hill introduced its newly opened galleries, which are mostly underground, and its first exhibition “Monanism” to a French audience, in the pages of Artpress magazine, Paris:

“Far away, in an island state previously known as Van Diemen’s Land, an eccentric 49-year-old mathematician and gambler has just opened one of the world’s strangest museums, The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA). His name is David Walsh and his collection includes ancient Egyptian mummies and priceless coins, as well as an altered Porsche by Erwin Wurm, Wim Delvoye’s Cloaca Professional, and Chris Ofili’s The Holy Virgin Mary. So far, he has spent over $200 million dollars on this “campus” and his annual running costs will be in excess of $7 million (admission is free). In a soundproof room, a 30-channel video installation by Candice Breitz shows fans of Madonna singing a capella tributes from her Immaculate Collection album. Two visiting American artists, Tora and Rya, are invited to perform real and telephone sex in an unadvertised cleaners’ cupboard (most people miss this – look for the red fire extinguisher and open the door beside it). Elsewhere, an underground tunnel leads to Anselm Kiefer’s bookcase of lead and glass books, and close to that is an on-going project – an autobiography, if you will - by Christian Boltanski, documenting every day of the rest of his life and paid for every 24 hours. Daily video links flash between the artist’s studio in Europe and the museum in Australia. The longer Boltanski lives, the more Walsh has to pay for the artwork. What are the odds? Ask Walsh – he’s the professional gambler.

Welcome to Tasmania, once known as Van Diemen’s Land. For my money, it is one of the most remarkable, beautiful, and dangerous places on the planet. I lived there for eight years and I go back as often as I can. Errol Flynn was born here and his swashbuckling history is still alive in its pubs and clubs. Many people first encountered this astonishing island, and its capital Hobart, through the writings of Jules Verne: “Dumont d’Urville, commander of the Astrolabe, had then sailed, and two months after Dillon had left Vanikoro he put into Hobart Town.”

PHANTOM LIMBS

See ALEXA WRIGHT

PIGVISION

PigVision is a Superfiction created by Swiss artist/scientist Raymond Rohner while he was studying at the Centre for the Arts, Hobart, Tasmania. He asks the question: “Do Pigs See in Colour?” The project sometimes takes place in galleries, sometimes at agricultural fairs or in scientific meetings. The text on his website (http://www.artschool.utas.edu.au/PigVision/pigvision.html) begins:

“Paul Feyerabend, a foremost 20th century philosopher of science, became known for his claim that there was, and should be, no such thing as the scientific method.”

Babyface fictional cosmetics company, Eve Anne O’Regan, 2000. Photo courtesy of Eve Anne O’Regan. © Eve Anne O’Regan.

EVE ANNE O'REAGON

Creator of the Babyface Cosmetics Superfiction. The artist uses graphic design and elements of advertising in her gallery-based work.

KARL POPPER

Karl Popper’s teachings on “sophisticated methodological falsificationism” relate to Superfictions in terms of how we approach different visual truths. We can sight any number of white swans, he tells us, but we will never be able to say “all swans are white.” Whereas the single sighting of a black swan does allow us to say “not all swans are white.” Thus we approach the truth through falsifictionism rather than verificationism. See also Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend.

ORLAN

Orlan’s best-known Superfiction is her own body and the changes she has put it through. Her aim is to change her physical appearance through plastic surgery until it resembles the male Renaissance artists’ view of the ideal woman. Also known as Saint Orlan since she baptised herself with that name in 1971.

OSSIAN

‘Ossian’ is the narrator, and the supposed author, of a cycle of poems which the Scottish poet James Macpherson claimed to have translated from ancient sources in the Scots Gaelic. The furore over the authenticity of the poems continued into the 20th century and as such here are parallels with the Australian Ern Malley.

‘Ossian’ was supposedly the son of Fionn mac Cumhaill, a character from Irish mythology. See Wikipedia for further clues.

PATRICK POUND

Patrick Pound is a New Zealand-born Australian based in Melbourne. He has created many Superfictions, often submitting his fake identities to Who’s Who of Intellectuals and the Who’s Who Hall of Fame. Pound frequently uses a black and white photograph of East European soap carver Lester Gabo in place of his own. Pound also uses the name Simon Dermott, particularly for book reviews (See Photofile No 59, p 61 and p 63)

RALPH RUMNEY

Ralph Rumney was the founder of the English Psychogeographical Society and later a founder member of the Situationist International. Always one to back out of the limelight, he does not appear in the group photograph of the Situationists, taken in Cosio because he took them. Ralph Rumney was a painter who gave up painting (and has returned to it); an artist who regards artists as generalists whose primary function is to question, he has had a career in which both possibilities have been lived through. The interview is one aspect of his art, as is his conversation, as are the derives on which one might find oneself in his company, as are his writings.

For a three-way discussion between Ralph Rumney, Peter Hill, and Alan Woods see: www.superfictions.com. Also see SITUATIONISTS

Cindy Sherman, photo taken in Queensland Art Gallery Press Office, Australia,

by Peter Hill, April 2016. © Peter Hill.

CINDY SHERMAN

Cindy Sherman’s early film stills, portraying herself in various roles - hitchhiker, babysitter, waitress - place her firmly at the forefront of female artists who question identity through the use of fragmented narrative. Her project continues, most recently at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in Brisbane (June 2016), Australia, where she adopts the persona of ageing women, often in outlandish clothing and heavy makeup.

SITUATIONISTS

The Situationist International evolved from a synthesis of various pan-European art movements and revolutionary philosophies including the College of Pataphysics; COBRA; the Lettriste Movement; the Lettriste International (LI); the International Movement For An Imaginary Bauhaus (IMIB); Asger Jorn’s Institute for Comparative Vandalism; Group Spur; and Ralph Rumney’s Psychogeographical Society. Its key members included Guy Debord, Ralph Rumney, Michele Bernstein, Alexander Trocchi, Asger Jorn, Isidore Isou, Gianfranco Sanguinetti, Raoul Vaneigem and Wolman. However, it was always a loose alliance of people and movements and many others were involved. Guy Debord is now regarded as the leader of the group, although it is debatable whether such an anarchistic conglomeration could ever allow itself to be ‘lead’.

THE SORBONNE CONFERENCE

A landmark conference in Paris (2006) organised by Dr Bernard Guelton on the theme of Art, Fiction, and the Internet (les arts visuels, le web, et la fiction). Artists and theorists who presented papers included: Jean-Marie Schaeffer, Jerome Pelletier, Kendall L. Walton, Jacinto Lageira, Marie-Laure Ryan, Peter Hill, Alexandra Saemmer, Monique Maza, Yannick Maignien, Andy Bichlbaum, Lorenzo Menoud, Jean-Pierre Mourey, Alain Declercq, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreidge, Eric Rondepierre, Melik Ohanian, Yann Toma.

For more conference details see: www.superfictions.com and the conference publication: ISBN 978-2-85944-636-9

SUPERFICTIONS

A term coined by Peter Hill to describe new uses for fiction in the contemporary visual arts using all media including the internet and the postal system. See other listings in The Encyclopaedia of Superfictions.

SUPERFICTIONS 2: AS IF

This exhibition of global Superfictions, curated by Peter Hill (Scotland/Australia) and Adeline Kueh (Singapore) was held at Kings ARI, Melbourne, from 26th September 2014 to 18th October 2014. It brought together the work of 11 artists:

Adeline Kueh

Cameron Bishop

Grant Hill

Jacquelene Drinkall

Michael Vale

Nathan Coley

Neon Kohkom

Patrick Pound

Peter Hill

The Institute of Critical Zoologists

Urich Lau

As if, curated by Peter Hill (Aus/Sco) and Adeline Kueh (Singapore), brings together 11 artists whose work explores fictive narratives through painting, sculpture, video, and installation. These range from Turner Prize finalist Nathan Coley’s collaboration with Cate Blanchett – a meditation on the laneways and dark alleys of Melbourne and Glasgow – to Melbourne painter Grant Hill’s images of suburbia that look “as if” they are something else. Several contemporary artists have, in recent years, investigated the animal and plant kingdoms, but few so poetically as the Singapore-based Institute of Critical Zoologists (aka Robert Zhao), represented in “As if” by a complex artists’ book. This is a celebration of the strange forking paths that confront our imaginations in the garden of Superfictions.

See AUTHENTICITY...?

Aesthetic Vandalism Robert Nelson, art critic for The Age newspaper

(Melbourne), suddenly slashes a canvas by Peter Hill’s fictive artist Herb

Sherman, during the opening of the exhibition As if: Superfictions 2 at King’s ARI,

curated by Peter Hill and Adeline Kueh, Australia (2014). © Peter Hill.

SYNTHETIC MODERNISM

In the early 1980s, Peter Hill became frustrated with the (over)use of the terms modernism and post-modernism that seemed to go head-to-head like sporting teams in an unhelpful binary opposition. He coined the term “synthetic modernism” to cover the grey area between modernism and postmodernism and found it useful as a way of describing the art of the Superfiction.

BOONSRI TANGTRONGSIN

Boonsri Tangtrongsin is a Thai artist currently working in Scandinavia. She is the inventor of “Superbarbara” a non-archetypal heroine that takes the form of an inflated sex doll. Superbarbara was exhibited as a single-channel video made up of 11 episodes in the 2013 Singapore Biennale. According to the catalogue: “Although much of Superbarbara’s encounters are allusions to social realities in Thailand, at the heart of these works are philosophical conundrums that are universal in human existence. By transforming Superbarbara from a sex toy into a saviour, yet positioning her as both victim and valiant hero, the artist reflects on the potential of ordinary people to play the role of heroes.”

Boonsri Tangtrongsin and Superbarbara were curated into the exhibition Faux Novel at RMIT Project space by Peter Hill and Anabelle Lacroix, from 26th September to 23rd October 2014.

THIRTEEN MONTHS IN 1989

See THE ART FAIR MURDERS AND THE AFTER SEX CIGARETTE

TORCH GALLERY

This Amsterdam Gallery run by the late Adriaan Van Der Have was pioneering in its support of artists working with Superfictions including: Guillaume Bijl, Res Ingold, SERVAAS, Seymour Likely, Gary Carsley, and Peter Hill.

SUZANNE TREISTER

Suzanne Treister is the founder of the Institute of Millitronics and a widely exhibited artist, including in the 2002 Biennale of Sydney (The World May Be) Fantastic. One of her most endearing creations has been the time travelling Rosalind Brodsky who is like a cross between Dr. Who and Woody Allen’s Zelig (she mysteriously appeared on the set of Schindler’s List alongside Ben Kingsley).

Treisters’s book No Other Symptoms: Time Travelling with Rosalind Brodsky is described in the catalogue to the 2002 Biennale of Sydney (The World May Be) Fantastic: “Loosely resembling an adventure game, the story is set in 2058, at an institute of esoteric advanced technology. The facility is crowded with paraphernalia through which visitors can explore Brodsky’s life and adventures…In the bedroom a large Introscan TV screen shows excerpts from Brodsky’s career as a television cook, where she loftily disregards the laws of physics with a recipe for converting gâteau into Polish pierogi dumplings.”

MICHAEL VALE

Creator of many Superfictions, Vale is perhaps best known for his Smoking Dog series of works, including the award-winning video set in various locations including Venice and Paris.

DAVID WALSH

See MONA

ORSON WELLES

Orson Welles’ U.S. radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds was one of the earliest and most successful Superfictions. Across the country, listeners tuned in to what many believed to be an invasion of Earth from outer space. Sadly, there was at least one death caused by the panic on the streets and freeways.

FRED WILSON

By commenting on the place of African Americans within U.S. museums – and his projects often position them working as gallery attendants or cleaners, rather than customers and spectators – Wilson has caused many museum directors and curators to re-think their programmes and attitudes. He has also commented on the content of colonial paintings and their depictions of both slavery and domestic interiors. For one influential project, he dressed as a museum attendant himself and ‘lived’ in the gallery for a week – approaching white middle-class couples and interpreting the paintings for them.

ALEXA WRIGHT