According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), weather refers to a short timescale of local climate change, and climate change refers to the broader ranges of changes that are happening to our planet; and global warming is one of the aspects of climate change. Although these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, one thing is certain: “human activities are driving the global warming trend observed since the mid-20th century.”1 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) also declared that “human influence on the climate system is clear, and recent anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are the highest in history. […] Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and since the 1950s, many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia.”2 That said, climate change is never a physical phenomenon alone, with climatologist Mike Hulme arguing that it is also a set of cultural ideas (xxv-xxvii).3 In order to understand these ideas requires plural understanding of our relationship with the natural environment.

The liveability of a city is also measured by its sustainability and resilience – that is, how it is designed to provide for future generations and how quickly it can recover from shocks. These issues become more pertinent in an era of climate change, which pose more risks of extreme weather events and other disruptions. The arts are an important platform on which these issues can be explored.

—National Arts Council Singapore4

National Arts Council Singapore (NAC) in its latest Our SG Arts Plan (2023-2027) firmly puts the emphasis on the vital role of the arts in facilitating the discussion of these cultural ideas. Our understanding about the physical weather, climate change, global warming and environmental degradation is filtered through our perception of what they mean for us. How do we feel about them; sad, angry, fear, happy, or schadenfreude? Are the changes a threat, a challenge, a disaster, an opportunity, or a blessing? What do we want to do about them? Or do we want to/can we do something about them? Underneath these questions, it is all about us and our perception of sustainability. What defines sustainability? Who defines it? Driven by these questions, the paper focuses on the investigation of the project Alternative Ecology: The Community (2024), which aims to render a sensible network of ecological solidarity through creative practices. Different from the common approach of ecology that is rooted in the context of biology, Alternative Ecology discusses artists’ engagement with the crisis of climate change and environmental degradation. Through a combined mode of eco-aesthetics and action-driven inquiry that includes public art, discussion, workshops, talks, community gatherings, markets, guided tours and research sharing, I argue that the broad public engagement of Alternative Ecology with a multidisciplinary approach demonstrates a critical willingness in the humanities—artistic humanities. Artistic humanities, through the lens of art, bring the concern of environmental change more visibly to people’s everyday living—a genuine, ground-up approach for real change.

Alternative Ecology: The Community

Alternative Ecology is a project commissioned by NAC for Singapore Art Week (SAW) 2024 awarded from an open call selection. NAC’s commission award, in its vision of Our SG Arts Plan (2023-2027), reflects that the arts are the important platforms on which sustainability should be explored. The project has received additional support from Objectifs – Centre for Photography and Film, LASALLE College of the Arts (LASALLE), University of the Arts Singapore (UAS) and Zarch Collaboratives Pte Ltd. It was held from 13 to 28 January 2024 at the communal courtyard open-space of Objectifs and presented by the independent art space Comma Space. Conceived primarily as an art and ecology event, it was curated by myself and managed by artist Susanna Tan. The project consisted of three key components. The first, a sculptural social space titled Fragment of the Unknown Memory, made from bamboo by late artist/architect Eko Prawoto (1958–2023, Indonesia), which was constructed by his family and studio on site. The second, a series of programme activations, titled Bamboo Broadcast Studio, executed by Post-Museum (Singapore), which included some of their signature events, such as Really Really Free Market and Renew Earth Sweat Shop. The third, the curatorial activations planned by me, which included symposiums, eco-community booths and Sustainability Circle Meet-up. The project’s objective is:

to offer creative interpretations of the profound environmental challenges that we face today, and at the same time, explore the parallel role of an artist in acting as a catalyst for fostering community collaboration and promoting awareness through creative interpretations and discussions. This project demonstrates that art practices from the ground up come with a unique ‘magnetic field’ that connects the public, communities, professionals, creative practitioners from all walks of life to shape a liveable future.5

I consider Alternative Ecology an optimistic project embracing community as a key framework in defining the critical perspective on human relationships with our changing planet. It intends to create a site of alternative encounters to generate new possibilities in which art matters not only for viewing but also for taking action. Besides involving artists locally and internationally, the project evidentially has ‘magnetised’ people from disparate professions, allowing them to meet and communicate about the sustainability that matters to the everyday life of ordinary people, which I will explain further in the following chapters.

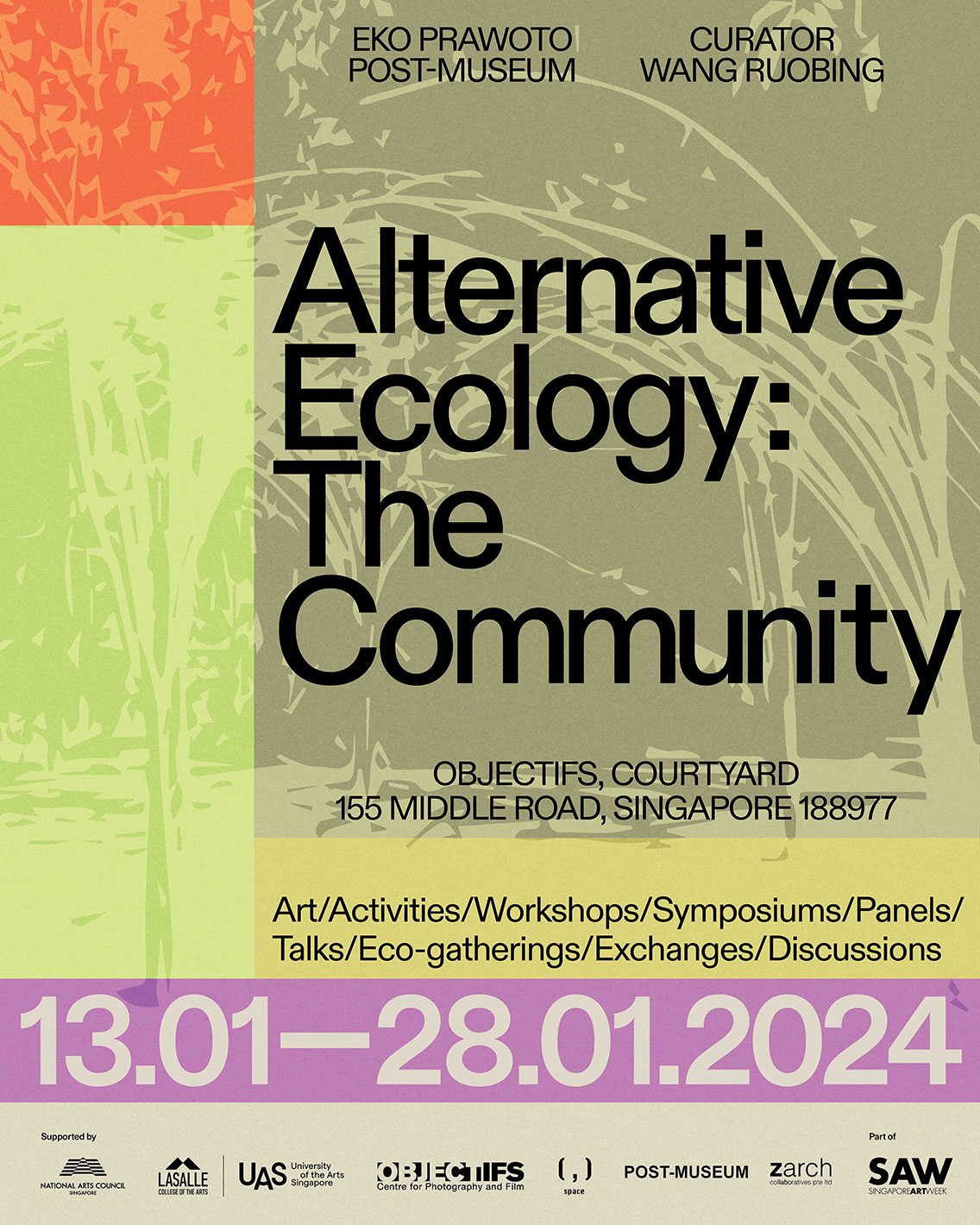

Alternative Ecology: The Community project poster

Crafting eco-aesthetics

Top view, Fragment of the Unknown Memory by Eko Prawoto, 2024

One of the critical components of the project is the use of the organic material bamboo to create a holding space – a social space. Being a member of the grass family, bamboo has a long history of being easy and flexible to use (wide range of species and heights) and environmentally sustainable (rapid growth) in its usage by humans. In early 2023, I started the conversation with Prawoto, a Yogyakarta based Indonesian artist/architect, to conceptualise a public art site specifically in the open space of Objectifs using only bamboo. However, Prawoto’s sudden passing on 13 September 2023 put the project on hold, with no certainty if it could still be carried out. Fortunately, Prawoto’s family and studio were determined to realise his final artwork in the most desirable way that he would have imagined. With their support and commitment, Prawoto’s final artwork, Fragment for Alternative Ecology, was hand-built by his family and studio on site as planned. The first activation within this space was the private memorial for Prawoto with invited guests who had worked with and known him in Singapore.

Private memorial of Eko Prawoto. Speaker Tamares Goh, curator of

Prawoto’s solo Garbha at the Esplanade–Theatres on the Bay in 2012

Private memorial of Eko Prawoto. Speaker Tegar Jati Prawoto,

youngest son of Prawoto

Ultimately, Fragment is conceived as a metaphor of ‘a better world’ underlined with a greener, humanistic and compassionate approach. It is an apt demonstration of Prawoto’s practice in believing “all humans share a universal connection to nature which defines our existence.”6 Prawoto is most well-known for his humanist and environmentally sustainable approach to his practices. He is a familiar name in Southeast Asian countries. His Wormhole, for example, the Singapore Biennale 2013 commission which consisted of three large bamboo mounds resembling the range of mountains in Indonesia, has been one of the most fondly remembered public art exhibits in Singapore. Tracing back, he first gained international acclaim taking part in the Venice Biennale of Architecture, Less Aesthetics, More Ethics (2000), which showcased his artistic, architectural rendering The Transitory Place: A Housing Project for the Urban Poor in Yogyakarta.7 Intriguing to notice that though the Biennale was dealing with the situation of less aesthetics, Prawoto’s artworks are indisputably beautiful. The appeal of aesthetics entrenched in the material of bamboo, as well as in the craft of the handmade, is irrefutable. The handmade is intimately tied to materiality. In the cultural framework of mass production, handmade is a sign, a symbol for anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation critique. Further, it demonstrates a mode of production that is tied to the inquiry of identity and culture in meeting not only personal but also collective needs.8

Side view, Fragment of the Unknown Memory by Eko Prawoto

Situated in the communal courtyard, which is heavily utilised by the general public on an everyday basis, Fragment, in its immersive scale and impressive handmade form, stands openly and elegantly, and cannot be unseen even when there is no programme activation. According to Herbert Marcuse, when “[i]n a situation where the miserable reality can be changed only through radical political praxis, the concern with aesthetics demands justification.”9 The beauty here embraced in Fragment standing solitarily occupying a newly claimed public space needs to be justified. In its upfront organic/handmade material state, Fragment visually enfolds the idea of eco-aesthetics functioning as an enquiry into the sensory knowledge of our natural environment that has been disrespected and ignored. It presents a delightful invitation, but at the same time, is a passive resistance to a society based on the values of capital. Along this line of thinking, the curatorial inclusion of Fragment offers, as what Kester argues, “the ability of aesthetic experience to transform our perceptions of difference and to open space for forms of knowledge that challenge cognitive, social, or political conventions.”10

Dialogical-based activations

As a structure, it is not yet complete. I would like to invite visitors to participate in the completion process. In that way, it will be our shared memory, our shared journey as human beings

—Prawoto11

Prawoto considered his structure incomplete without the engagement of the visitors. If we see his handcrafted Fragment as an open invitation for people to stop by and embrace, similar to those purposefully designed birdhouses hanging in the gardens waiting for the visit of birds, the programme activations by Post-Museum and me are a variety of ‘seeds’ curated to attract birds, i.e. the public. The public’s participation activated these programmes, and only with their engagement can Alternative Ecology be complete(d). Activations, utilised in this framework, are socially engaged, dialogic, action and community-based artistic social practices, which are, however, not new. As early as in the 90s, Suzi Gablik (1991)12 and Hal Foster (1996)13 have already discussed the growing need for contemporary artists interested in socially interactive art to resist bourgeois culture via making art to be useful and not just made for an aesthetic pleasure. In Singapore, community-based arts have a long history too, which has witnessed a substantial increase over the years.14 Nevertheless, in regard to art and environmental projects of this scale from a community and ground-up perspective, Alternative Ecology marks a new record. It initiated a total of 20 public activations and one private memorial hosted in the Fragment. Among them, 17 public activations were by Post-Museum, and four by me. The project attracted more than 1,115 active participants (directly participating in the activations) and at least 12,000 passive participants (the general public).

Post-Museum’s 17 activations in its totality are called Bamboo Broadcast Studio, comprising some of their signature programmes over the years. Post-Museum was established in 2007 in Singapore by husband-and-wife artists Jennifer Teo and Woon Tien Wei. They are widely known locally and internationally as “… a networked collective that creates situations and projects with local communities in order to understand and reimagine contemporary life.”15 They used to run a physical space in two shophouses on Rowell Road in the Kampong Kapur area between 2007 and 2011. During that period of time, their space was a popular network destination for cultural practitioners. Currently they are being nomadic. According to them: “Being ‘nomadic’ allows our practice to be ‘place’ driven. We are interested in how we can ‘practise the city’ in more meaningful ways. To ‘practise the city’ for us means asserting and claiming the ‘right to the city.’”16

Alternative Ecology offers a practising ground in the city centre that facilitated the “practice the city” and continue to claim the “right to the city”. As for myself, my art practices focus on our position with our environment in the contexts of ecology and knowledge production. Although I mainly played the role of a curator for Alternative Ecology, my approach to the overall project and the planning of the activations is, to a great extent, a form of artmaking, promoting the ideas of socially responsible art and building ecological communities through curating.

Our activations cover a wide range of community-based approaches, which broadly can be categorically defined as workshops, talks, education booths, free markets, tours and gatherings. The primary purpose for us is to enable the participation of people from various non-art sectors through artistic and creative means. For example, on 21 January in the hours 12–7pm, we hosted three activations. The first, Water Symposium, involved a moderator and speakers from Our Singapore Reefs, Stridy, Friends of Marine Park, Waterways Watch Society, Marine Conservation Groups, Nature Society Singapore, Young Nautilus and an independent artist, addressing the pressing challenges and exciting opportunities surrounding water conservation from the perspectives of environmental NGOs, scientists, volunteers and artists.17 The second, Sustainability Symposium, with a moderator and speakers from Nature Society Singapore, Singapore Youth Voices for Biodiversity, Post-Museum and LASALLE, discussed in depth how every one of us can take the lead to be change makers in coping with the challenge of sustainability.18 The third, comprises eco-community booths from Nature Society Singapore, Young Nautilus, Stridy and Textile Paper Lab presenting informative and hands-on activities for the participants and general public, raising environmental awareness. On that day we attracted a total of 157 direct participants from diverse professions. These activations effectively demonstrate that the bottom-up approach of making art is more relevant in formulating new social relations with like-minded grassroot organisations and individuals.

Water Symposium

Sustainability Symposium

“Alternative Ecology shared the official opening date of 20 January 2023 with two other indoor exhibitions organised by Objectifs: A Reservoir of Time and the 5th VH Award Exhibition. On the opening day, instead of providing buffets, like most exhibitions do in Singapore, we hosted Stone Soup Party—an interactive relational aesthetic practice. Drawing reference from the European folk tale Stone Soup, the party encouraged the public to bring along a vegetable (preferably locally grown and organic) and cook with us in the kitchen we set up under the Fragment. The soup with the participants’ contributions was shared with others. There were 278 visitors, with about half of them either bringing vegetables for cooking, and/or drinking soup from this sharing activation.

Stone Soup Party

Besides the bottom-up approach, we also hosted the Sustainability Circle Meet-up & Eco-Karaoke activation in collaboration with the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE). Through the network of MSE, Sustainability Circle received people from different backgrounds coming together, sharing their sustainable practices either for business or everyday life hacks, and engaging in thoughtful conversations. It was a magical and fun night in connecting other fellow sustainability enablers (individuals, companies, ministry, organisations; a total of 82 people) in finding available support to further their sustainability goals.

Sustainability Circle Meet-up & Eco-Karaoke

On its closing day, we activated Really Really Free Market. Started in 2009, Really is a temporary ‘free’ market concept based on alternative gift economy. Built on the valuable acts of giving, sharing and caring, the project creates a temporal physical manifestation of a micro-utopia where the fundamental economic structure is being questioned.19 It is in its 77th edition, which was hosted on 28 January from 10am to 4pm. It attracted about 150 participants from all walks of life. Placing Really as the closing event of Alternative Ecology reflects the project team’s mindfulness on resource sustainability. At the closure of the project, the team successfully repurposed all the materials used to build Fragment (bamboo and bases), so nothing went to waste.

A site for humanities – artistic humanities

For geographer Doreen Massey, space is socially and contingently constructed, which is always in the process of being made. It is a product of interrelations and outcome of multiplicity of encountering.20 Fragment craved out a temporary site in a busy urban space. Its elegant low-technological gesture offered an eco-aesthetic temptation in uplifting such an encounter of space-making. Not relying on Fragment‘s materialised physical form alone but paired with the programme activations, the newly but temporarily claimed space inspires a social and imaginative interchange that is open-ended, exploratory and becoming (process driven). The project is quite different from Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project (2002), which was created with lights, projection and haze machines, to generate a spectacular site of climatical experience in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Alternative Ecology, in contrast, in its totality, built by a humble dialogue-based community drawing inspiration from traditional and ancient knowledge. Besides the activations such as Stone Soup Party drawing inspiration from European folk tale in the early chapter, I would like to mention another activation, Animals’ Lawsuit Against Humanity. This is a reading performance led by the environmental and natural health educator Betty Khoo. She guided the participants to make animal masks, read the ancient animal rights tale from 10th Century Iraqi’s ecological fables, and then further presented the reading with a live argument between animals and humans resembling the format of a court hearing. A total of 25 children and adults from the public took part in the reading performance. Animals’ purposefully swapped the role of animal and human. Utilising dialogical-based participatory imagination, it put humans in the defendant’s position, forcing them to listen to others.

Really Really Free Market 77

The Animals’ role play acutely reveals that the temporary site created with Alternative Ecology is not owned by Prawoto, Post-Museum or the curator. Rather, it is co-owned, co-created and co-completed with the involvement of individuals, organisations, and local stakeholders from the ground, on the ground and for the ground. That said, Alternative Ecology has made a site—a site for humanity. It embodied the central concept of this project, which is fundamentally grounded in the ethic of care, conversation and respect engaged with active listening. Furthermore, it reflected the key curatorial framework in believing that environmental problems are a cultural and existential problem which requires understanding and awareness of our values and beliefs, and changing our basic ideas about how we should live. According to Kester, the arts eventually emerge in the discursive relationship established with the participants.21 In the case of Alternative Ecology, the arts arise from a process of conversation, individual and collective exchanges rooted in the humanities. Artistic humanities shown in the artists’ and curator’s active listening and empathetic care are visibly driven by the willingness to let the community shape their practices and themselves, which are established on a mutual influence.

Animals’ Lawsuit Against Humanity

Photo: Nor Lastrina Hamid

What underlines the artistic humanities manifests the broader concept of environmental humanities. Hubbell and Ryan argued that environmental humanities “demand that people from a range of disciplines listen to one another, participate in a lively dialogue, and contribute ideas to the decision-making process.”22 From the project participants’ statistics, we can see Alternative Ecology has drawn participants from wide diverse backgrounds hitting a record number within the 16-day exhibition period. The participants included yoga instructors, filmmakers, geographers, marketing managers, scientists, retires, freelancers, homemakers, administrators, government officers, entrepreneurs, environmentalists, students and educators. They gathered and sat under the Fragment, took part in the programmes to engage, meet, learn, listen and experience. Though these exchanges are limited in verbal conversation and hands-on activities, they are indispensably filled with exchange of values. Such exchanges may not necessarily successfully create an alternative ecology with a direct cause-and-effect solution. In view of the global environmental threat in its magnitude, depth and complexity, it would be implausible to insist that art can avert global warming. What matters the most here is the multi-dimensional understanding and awareness enabled by artistic humanities. Claire Bishop is sceptical of such exchanges in feel-good community services provided by art, which may have misguided people. She argues that “artistic models of democracy have only a tenuous relationship to actual forms of democracy.”23 Although I acknowledge Bishop’s trenchant charge on the discursive outcome of social practices, I maintain that though it is difficult to provide statistics to prove the effectiveness of socially engaged art, the impact of such practices should nevertheless not be underestimated.

Curator Cecilie Sachs Olsen believes that “socially engaged art can work as an active and generative force in questioning given ‘truths’ and identities.”24 Likewise, art historian Wang Meiqin acknowledges that “[f]undamentally the purpose of SEPA [socially engaged public art]… is to enable people to work together to activate space, place and community that matter to the everyday life of ordinary people.”25 Once in an interview, Post-Museum said, “We believed that art should change the world, or it should participate in shaping a better world”.26 Post-Museum is clearly an optimistic and firm believer of the social responsibility of an artist. Echoing their views, I believe that art projects embracing artistic humanities rising from the ground for the community can play a critical role in contributing to compelling cognisance of the cultural ideas that Hulme reminded us to face today. Taking shape from both object-based (Fragment) and non-object dialogical based practices (activations), Alternative Ecology shows, in its broad multidisciplinary approach and humanistic curatorial framework, that contemporary artists today seek to more fully integrate their roles into the real-world issues by engaging the public and claiming the public sites. Artistic humanities are the humanities constructed through the processes of exchange, appreciation and communication between the artist, curator and interlocutors. This is based on a holistic approach in learning from and listening to each other respectfully. Artistic humanities are of critical importance in bringing climate change and environmental crisis into discussion, and in defining the set of cultural ideas on our relationship with the changing planet.

Unless otherwise stated, all photos: Comma space/ Wang Ruobing.