ISSUE editor Venka Purushothaman in conversation with artists Tran Luong, Mithu Sen, Milenko Prvački and weatherman Huy Nguyen.

This conversation occurred in the ancient city of Hà Nội in Vietnam at APD Center (Art, Patronage and Development), on 21 and 22 March 2024. The discussion aims to be as close as possible to the participants’ comments within the vernacular expressions and has only been edited for clarity where needed. The original transcription was considerably longer; the present form is a focused rendition.

Inner Voices; River Stories

Venka Purushothaman

Thank you, everyone, for joining us.

ISSUE art journal is committed to giving artists a voice, not through their art but by listening to what they’ve got to say. Because artists are often rather silent when their works speak for them in many ways, this conversation aims to open a multidimensional space to explore your methods, materials, life, practice, and concerns. For us at the journal, the conversations are an important part of constructing an emerging artist ecosystem for our contemporary times.

The conversation is centred around the theme of Weather. We were quite concerned that there is deep concern and obsession with climate change, which is important. However, it has also become a distraction from other core concerns in society. For example, rising poverty, emerging youth populations, ageing communities, etc., are equally fighting for attention. So, we wanted to look at the concept of weather as a broader idea. One that looks at the condition of artists—what is the weather of our time? What is your weather?

We want to focus on three things. One of which is to invite you to share with us your current artistic practice, what you are currently working on, and why. Second, we are interested in your material, from objects to ideas, and thirdly, what are the kind of concerns that are preventing you from achieving what you’re doing in your practice, right?

Milenko Prvački

Weather influences us, as artists, definitely. It influences us in creating and rethinking our practice and the place where we’re staying. When Venka mentions our own practice, it’s not the presentation that you have to show but talk about how your practice is affected by weather or climate change. I have to say we cannot avoid politics, especially in Southeast Asia, because there are similar issues, and we will not publish anything you find that’s too risky for you.

Tran Luong: Artist as a social community developer

Tran Luong

Thank you for coming to my space. I am busy preparing for big works and preparing a book to be published by Mousse Publishing House in Italy. A retrospective of my work is being planned to be toured from Dubai, Australia, and New Zealand. My work cannot be shown in Vietnam. It contains politics and is sometimes also banned. People here have not seen my work.

Also, I have been involved in social development work with the UNDP1. So, in some projects, I play the role of a curator. From 2010 to 2012 ed, Riverscapes in flux2,invited and this was followed by an exhibition tour through Vietnam, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines for the next 2 years. Unfortunately, the project did not include Singapore because you don’t have a river. The project enabled artists from Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia involved, to go to a site for four months and study the environment and create work. The activity is on the engagement of artists with the environment rather than an exhibition. Artists have to learn how activists approach environmental and climate changes and discuss this with the curators. The project pushes the curators out of their ivory towers to work, dialogue and learn.

I must say that every project we have undertaken since around 2005 has already concerned us with the impact of climate change and global warming at that moment. Also, the dam construction in the Mekong River is of concern. The government does not like activists talking about the dams by the Chinese. The damming in many places, funded by Chinese money in places like Laos, is destroying the ecology of the Mekong Delta. We often hear in the news that an entire row of houses had fallen into the river because of over-construction.3 A lot of people fall into the river and die. In the last ten years, the damming upstream has reduced 35% to 40% of water coming downstream. That’s why the level of freshwater is not enough, and then the seawater seeps into the land. Rice farming in Vietnam has come down because the salt water comes 80 kilometres deep into the Mekong Delta.

Milenko Prvački

No one follows international law, or they are not obliged because it’s not their own river?

1 United Nations Development Programme

2 The project was sponsored and organised by the Goethe Institute Hanoi in collaboration with Goethe Institutes in the region.

3 According to Tran Luong, entire rows of houses collapsed into the river because the banks of the Mekong River collapsed. Riverbank erosion began to increase sharply in 2000 after China built eight dams on the upper reaches of the Mekong River. In the past, the highest average water flow speed was nine metres per second, but since the dam system and river bed improvements, the water flow has reached 13 metres per second or even more, which has impacted the riverbank causing landslides.

Tran Luong

Yeah, no one actually likes a water war. All Mekong River countries only look at immediate benefits, lack responsibility and vision, and China wants to control water resources as a political and military means, and direct water flows for internal purposes in their territory. So, we organise ourselves as a civil society and work in the mangrove forest in the Mekong Delta. But we get into trouble with the government and the corporations. You have to grow mangrove forests to protect eroding seashore. Because there is an increasing lack of flood water from the upstream due to the increase in the number of dams, higher sea levels have eroded into the mainland, and strong waves during the monsoon season wipe out mangrove forests and cause coastal erosion, each year depending on the region. We have lost land along the coast, the heaviest is the Mekong Delta, with some places lost from 35 to 50 metres per year.

Venka Purushothaman

Can you share with me how your interest in social development was formed? Where and what did you study?

Tran Luong

I came from a very backward European academy in Hanoi called Indochine École des Beaux-Arts. That is the only degree I have officially. The school was established by France in 1925, almost 100 years, and was one of the very early academy art schools in Southeast Asia and the Mekong region. People came from Phnom Penh, Bangkok, Saigon, and went to Hanoi to study. The school was a copy of École de Beaux-Arts in Paris and two professors from Paris, came to the founding of the Hanoi school. The school was very French style, very European French style. For about 6 decades, students from Saigon, Cambodia and Laos had to come to Hanoi to study at this school.

I studied during the war, so we spent a lot of time on field trips. I was born during the Cold War in 1960, and I was five years old when the Americans bombed Hanoi and North Vietnam. All children and women had to go to the countryside to hide from the bombing, so I did not go to school until I was 12 years old. I was actually born into an intellectual family quite high class, but I actually grew up as a countryside boy.

The first time they (the government) sent us to the countryside with our parents, they said it was for a few weeks. But finally, we were in the countryside in a different province for seven years. There was no school there, so I was self-taught. In fact, there are still schools in the countryside, but because of the war, sometimes the schools are open, sometimes they are not. Also, city children like us cannot attend school in the village, because every once in a while we have to move to a new location, which can be a way to ensure our safety. I have good skills in catching fish and swimming in the river, and that is attached to my artworks a lot, until today. I am totally a countryside boy.

The end of 1972 was the hardest bombing, which destroyed Hanoi a lot. And the Americans destroyed the whole country—like they say, carpet bombing with B-52s. They have big B-52s and throw small bombs 20sqm to each corner. So it’s like, destroy everything! And when they bomb, that means they make everything flat. And in Hanoi, they make the whole Kham Thien Street flat, killing thousands of people.

Tran Luong’s performance at the opening exhibition Polyphony Southeast Asia at AMNUA Nanjing, China 2019.

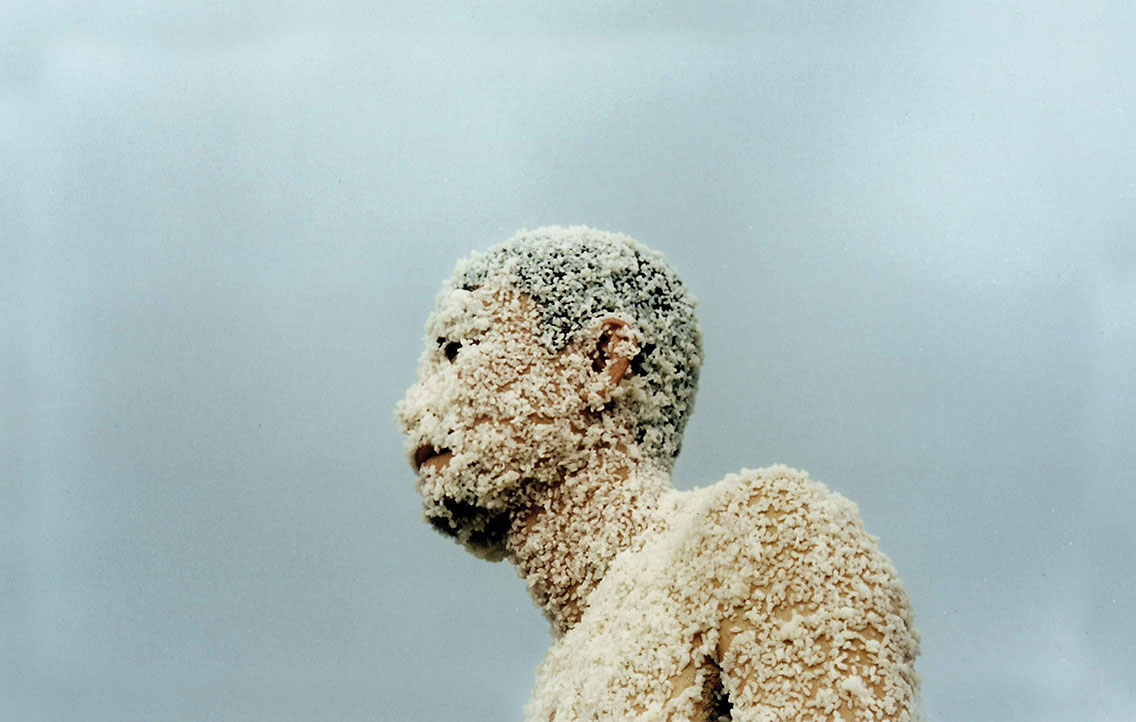

Steam Rice Man: Luong’s durational performance at Mao Khe Coal Mine Factory, 2001

So that moment, unfortunately but luckily, we were in town, because nothing had happened (no bombing) for a few months, and it was very peaceful. So whenever there is no bombing, people come back to the city. So I’m 12 years old, happy to stay in Ha Noi for a few months, and nothing happened. But suddenly, over 12 days and nights in December 1972, bombs flattened Bach Mai Hospital, killing many doctors and patients, bombs entered the French Embassy, killing the ambassador and his wife, and bombs flattened Kham Thien Street killing thousands of people, bombs destroyed the entire main building of Hanoi railway station, and many other places in Hanoi. That I’ll never forget.

They say 12-day carpet bombing. And you know what kind of bombing? Both sides used violence to negotiate for peace in Paris. They sit in Paris for many years; they say, please, submit an agreement between America, Russia, and two countries—North Vietnam and South Vietnam. They negotiated from around 1968 until around 1972, four years. Whenever the negotiations were stuck at the table, they started killing people. Communist troops fought with American troops and the southern government troops in border areas, they also terrorized with mines and raids right in the cities of south Vietnam. American bombs in north Vietnam killed normal people. And that’s a negotiation for peace. So I grew up from that.

Venka Purushothaman

The negotiating model hasn’t changed even today.

Tran Luong

Yeah, you see Kosovo, everything after that…

Milenko Prvački

You mentioned that you don’t exhibit here in Vietnam. I suppose this is the kind of decision artists make when they are impotent to change the system. You can be loud, but you’re not allowed to be loud, then you create another world, and you do something else. And I think these conditions also include weather and rivers.

I like this idea of the river, that’s why we went last year to Phnom Penh. I was born on the Danube River, and the Danube River connects most of Europe, from Schwarzwald in Germany to the Black Sea in Romania. Just like the Mekong. But they have wars over rivers.

Venka Purushothaman

How about your experience, Huy?

Milenko Prvački

You don’t have to talk about art as we want views from everyone.

Huy Nguyen: Weatherman

Huy Nguyen

You might find some art in my story!

I started to study the weather, climate change and disaster twenty years ago when I finished my PhD at Kyoto University in Japan. I started with a study of drought conditions in the Mekong region, especially in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, between 2005 and 2006. Then, recently, I studied other countries like Bangladesh, Marshall Islands, and Indonesia. Most of the researches focus on how the local people adapt to extreme weather conditions. For example, in the areas of prolonged drought, meaning lack of water, I am interested in understanding how local people deal with it, using their traditional knowledge of prediction of weather and navigation over the ocean. It is interesting to see how knowledge changes from generation to generation. On the shores of the downstream Mekong Delta as well, understanding how the local people apply the weather forecast for their livelihood is important. Before they have smartphones; they can access weather information more easily. Before smartphones, people observed nature around them and had traditional knowledge transmitted through folk songs to predict the weather—like seeing the dragonfly…

Redemptorist Church in Hue city, Vietnam during the flood event on 15 October 2022.

Photo: Nguyen T.A. Phong

Manor area, a new developed area of Hue city during the flood event on 15 October 2022.

Photo: Nguyen T.A. Phong

Tran Luong

They fly at a very high level when it is sunny, low when it is rainy, and the middle level in normal conditions. In Vietnam, everyone, including myself, every morning, if we see a dragonfly, we will know the weather of the day.

But now urbanisation has destroyed everything and the young generations don’t know what it is.

Huy Nguyen

So those kinds of tradition, they put in the traditional song as well, and the poem. And it’s seeing the sun and the moon, and the prediction for the weather condition in the coming days. And so observe the plants and vegetables at the sea, and animals like ants, you know, as to observe the behaviour of ants, when groups of ants move up to higher floors, it means that there will be heavy rainfall coming soon. So, that kind of indigenous knowledge has been applied in many of the communities around the world.

So I was trying to see if it works in Vietnam, and can it in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Laos and Indonesia, as well. When I did my research inland of Vietnam and Indonesia, the people living there observed the mangrove leaves, and if the mangrove had young leaves growing up, it meant that there would be rain very soon, in the coming days. So, much of the traditional knowledge has been applied for a long time before, but it’s for the old people who can know and remember about it. But younger people do not do so, as they rely on technology, such as radio, and information from their cell phones. So traditional knowledge somehow had not been applied and transferred to the next generation.

Venka Purushothaman

What you say reminds me of the 2004 tsunami that hit Southeast Asia. Research shows that, particularly in Sri Lanka, many animals started to migrate inland weeks before the tsunami hit. People didn’t pick it up because we’ve become so urban that we have lost our sensing of the fact that we as humans are actually part of the environment, and urbanisation has actually disassociated us, our connection to the environment.

Milenko Prvački

Because it was normal local oral communication and kind of transition from grandfather to grandfather to father. And then because you have readymade information now, and nobody cares about nature. And this is a bit of a problem, because they can’t predict some things in advance, they can’t anticipate. Usually weather report is what is it about yesterday or today. But what we’re talking, it is about generations, and it’s about anticipation through nature.

Huy Nguyen

Similarly in Vietnam, I watch the weather forecast information on TV and it’s very funny. I open the forecast news, in 2000, in 1999 or in 1990. The weather forecast from the national centre, meteorological centre remains the same. It means there’s no change on the way of the weather forecast.

It’s very general information, like—tomorrow, some parts of the region will be rainy, some parts of the region will be windy, and visibility will be 10 kilometres. That alone shows that the local people are not really relying on the weather news from local television.

Because of this, I have my own weather forecast channel, and there are about half a million people who follow it.

Milenko Prvački

Half a million people, wow.

Tran Luong

He turned out to be a dangerous person, and the government started watching him because he has a half million followers. Ordinary people going to work can learn each day his show. And each day he says to people in an area to be careful: you clean up things; or go back to the seashore, because the weather will change soon. And people follow him. He is so famous now that the government wants to meet him.

Milenko Prvački

When I was young, I was listening to the weather report, but it was called a water report. So, the change in the Danube River in Germany will affect people who are travelling by ship or boat or fishing or whatever. And then there are sea reports and ocean reports because many people are going from the Mediterranean to the Philippines, you know. So they can listen to what is the situation of the water, what kind of weather, what level, how to navigate. They don’t do this form of specific reporting anymore.

Huy Nguyen

And another part of my research work recently, I was trying to see the correlation between the people in the Mekong Delta and their reasons for leaving their hometown to some other parts. Is there a correlation between people leaving their villages in search of jobs and the weather condition? Actually, there is a close correlation. For example, just after the historical drought in 2016, the number of farmers who left their farms increased the following year because they had no income in the fields and they had to move to Ho Chi Minh city and other places searching for jobs. Many people are permanent migrants. They’ve not gone back to their homeland.

But why not go back to their homeland? The problem is that if they go back, they don’t know what to do for their incomes because of the very hard conditions. The intrusion of salinity into the fields and the low productivity of agricultural products, the impact of the many dams upstream of the Mekong River just stopped water flow for fisheries to survive. The biodiversity in the lower Mekong delta has been impacted. Before, it was easy for people to live; it’s like they could catch fish, they could get some vegetables around the fields, to survive on their lunch and dinner, you know, for food.

But now, it is money or nothing. They have to pay. Before, nature provide food and water to people. Now people have to pay for water and food. That’s why many of these people migrate out of the Mekong and many are in debt with banks. Many take loans to start some agriculture or aquaculture project. And then it collapses, and then they are in debt, they move out.

These have some relation to weather conditions, particularly the prolonged drought, salinity intrusion, etc. They impact everyone, including our children. You know, in one family, one parent leaves for a job search in the city, so the children also lack parental support. And then some of them drop out of school, or the education is not good for them as there is no one taking care for them. That will impact the future generations.

Milenko Prvački

Domino effect.

Huy Nguyen

Yes, that’s right. That will be generation effected in the future.

Venka Purushothaman

Perhaps Mithu, we’ll come to you? We’ve heard some very interesting and strong perspectives.

Mithu Sen: Language and poetic Interludes

Mithu Sen

I hear such strong perspectives on weather and ecology, and you both are working so intensely with this idea or this, you know, situation. Whereas I’m an artist who is definitely not working on issues related to climate change and weather, though I can see that they are serious in today’s time.

I can see my work related to the human condition and affected by different kinds of politics and situations and balances. And so if I extend that idea of how this balance happens definitely, climate change is one of the issues. But that is again kind of connected with politics and the different kinds of demographic and economic and political conditions in different places. Not only particularly in my country but as a whole, how this whole general nature of human violence affects us over centuries.

I can give some examples from my work. Recently, I was working on a project with Khōj and World Weather Network, five artists were appointed to do something about the weather and the weather conditions in India and other places.

So I was given only one key phrase: 28th degree north parallel, which is actually one big line from one part of this country (India) in the west to the northeast. Interestingly, my studio is situated on this line. You know it’s in Delhi, and it starts from Rajasthan. I actually travelled to the northeast states, to Assam and Arunachal Pradesh border, following a river. Again, this river, the Brahmaputra, connects China, Tibet, India, and Bangladesh. My work is definitely not related to hardcore research and data, so I cannot put myself into that category. Rather my practice is based on human instincts and speculative intuition.

I perceive something as an issue like weather through metaphorical keywords like river and execute it as a speculative future. So that project I did with the river, it’s called I Bleed River4 and was dated 2124, so 100 years from now, how it becomes. So, I made a film, of course I was recording and shooting my journey for a week through the river.

But finally, I made one film, which is like out of four seconds of footage. It was after the high tide, you know, like during the low tide, in the back of the river, there’s left a little pothole full of water, because the tide is like the whole river has gone back to its place.

4 See cover for image.

Milenko Prvački

The remains.

Mithu Sen

Yeah, the remains of the water, and somehow I was so emotional. I felt trance-like, and I started seeing the future through this tiny pothole water body. I was in extreme fear that this was what was going to happen to the river a hundred years from now—a little remains.

So I cannot explain why, but definitely it was last year’s end, and when the Israel and Palestine war started, and the bombings were happening. So you know my whole thing is very imaginative, and when we fictionalise, I start seeing the rains, bombing like everywhere. So with the whole violence of war, including the Ukraine and Russia war, instead of working on weather-related things, I actually started researching the wars and the associated violence in the last maybe one year.

I made this imaginative video out of the four-second footage, where a river is burning – the edge of the river was on fire due to petrochemicals. There is a big projection of the river burning, and I kind of explained in four lines what violence is from Gaza to Kyiv. Because of war violence, our nature is becoming ashes; it’s ending.

Milenko Prvački

Just again, to connect the war and violence to the Vietnam experience.

Mithu Sen

Yes, yes, all countries.

Milenko Prvački

I remember, as a kid, looking at the destruction of Vietnam. It changed the environment because such an intense bombing changes the environment.

Mithu Sen

Lots of technical disruptions are happening, like deforestation and world pollution, forcing migrations that happen. This human-made systematic violence is affecting nature and our human life. It is traumatic. People are migrating and cannot reverse migrate, that is, return to their homes.

All these things make me think of the future and how I can also use my own freedom, leverage my practice, and execute something provocative so that people are provoked to think and act. I use this method in my practice by deliberately and intentionally creating some fear of what might happen.

Milenko Prvački

I think it’s important. In our previous dialogues, we could not separate politics from the lives of people in Southeast Asia.

Mithu Sen

Here, the politicians build dams and prevent the next countries from getting the water. You know, between India, Bangladesh and Pakistan we also have these issues, especially regarding the causes of drought, flood etc.

Everything is interlinked and interconnected, and the nature of violence is ever-present.

Milenko Prvački

You can’t ignore.

Mithu Sen

You cannot ignore. As an artist, this affects me a lot. And I really like to think about the kind of emotions as humans become traumatised and how their behavioural nature changes. So everything affects, you know? If I see somebody cutting down nature like trees and plants in the name of cleaning the city or something, I feel this is a kind of violence and inhumane. Which is repeated in the name of civilisation.

Venka Purushothaman

What sets the stage for you for these points of enquiry?

Mithu Sen

My mother is a poet and I was born in a very culturally aware intellectual family surrounded by music. Even being a Bengali family from Kolkata, we never lived in the city— rather moved to different places, mostly near the Himalayas because of my father’s work.

I went to study in Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan, Bengal. As you know, it is an open school. We used to get classes under the trees. You know, it rained, and it sounded very romantic. It’s only 25, 30 years ago, but it’s still very much the same today, as if it is part of nature. We did have classes in concrete buildings, but we hardly were there. We always used to bicycle, go around, and feel the weather on our skin. That was my upbringing, for seven years studying there.

Then I moved to the capital, New Delhi, which was a horrible experience because I had never been to such a big city. I started confronting different kinds of politics, including the social, political, and economic lingo—everything that was confronting. India, as a post-colonial country, has many hierarchies and hegemonies. I felt very less powerful, and my own identity crisis started very strongly.

It’s not very good right now in India as censorship is increasing. A lot of censoring in the last couple of years, especially the last 18 years, including my own practice. I never thought that my kind of art, from an artist who is directly not connected with strong politics is looked at. Even I can be under surveillance, my work can be censored. And this is happening, and this is experienced at different levels. It’s happening in a very subtle way, under the table like just. So, as an artist, what I constantly try to do is like as a trickster, I try to subvert and sabotage that kind of censorship and try to play and roleplay.

I was restless. Earlier, I was more like a poet because I wanted to be like my mother. I started writing at an early age and published my books in Bengali during my university days, so I had confidence that I understood things. But migrating to a different city for a job gave me a completely different idea of identity—rather, identity as a struggle. The contrast between Santiniketan (open and kind of equal) and Delhi (chaotic and unequal) was jarring.

My practice is also based on radical hospitality, which is about deconstructing regular role-play. My medium evolves to prevent the art market from getting to me to produce the same type of work. I resist that and keep changing my mediums every few months. This upsets the galleries. The art market tries to put artists in one kind of frame and try to glamourise and glorify one kind of style or identity, encouraging the artist to repeat the same thing. It’s a trap. As a feminist artist changing my approach constantly is my politics, where I intervene and disrupt the patriarchal shape of the market.

Milenko Prvački

As artists, we are all migrants in some form. Some people migrate physically, but most of the time, we migrate intellectually to find our own space. I find it’s quite common.

Radical instinct

Venka Purushothaman

I think it’s quite an interesting jumping-off point. One of the connecting ideas around all of you is how you find your space since all your actions have been very instinctual in many ways. It’s not theoretical, it’s not ideological, it’s instinctual. How do I respond to the conditions of my time? You know, just what you’re talking about, having your video channels and the weather, it’s instinctually building on histories that people have known, receive knowledge. And instinct is quiet; it’s often not used in the kind of creative space.

Tran Luong

Art today has become more classical and formalised.

Venka Purushothaman

That’s right, today, because today we live very much in a data-driven space. So the kind of instinct that drives us as humans is muted or it’s disappearing.

All of you talk about the fact that instinct also depends on how someone is going to look at it. Some would look at it as radical. Some would look at it as just ordinary. But through whose lens? If someone sees Huy’s work as 500,000 people watching, that means that’s radical. Alternatively, it could be simply, oh my god, 500,000 people are interested in me?

Or the fact that Tran, your works are only being shown outside of Vietnam and not here. Then how do you make that connection in spaces like these that we are sitting in? So some might see it as radical, and some might say it’s quite ordinary. Because the instinct ties back to some sort of radical practice. But radical not in the kind of the political sense, alright, but in terms of a practice.

How do you follow through with your instinct?

Mithu Sen

I do a lot of sabotage and subversion in the digital space. I kind of have a couple of Instagram accounts; one is for the conventional art market, very nicely done. Then, in parallel, I have another one, and then another two anonymous accounts that enable me to play and explore. I try to see who is following me, and I interview them when they like something that is not associated with Mithu Sen’s ‘popular’ aesthetics. I don’t hack, but change the information on my Wikipedia page. So I appoint students or interns who can do this. And it goes unnoticed. So you can also challenge that authentication, how much we can authenticate, I like to keep changing my data pathway. It is a kind of violation.

Milenko Prvački

Maybe subversion instead of violation?

Mithu Sen

No, what I’m saying is that, from others’ perspective, when I’m actually disrupting, I become a violator. Twenty years ago, I had a show called I Hate Pink where gender politics was addressed and colour was addressed as a violation, and today, in India, the saffron colour often violating us, as a political symbol.

From colour, I move quickly to perhaps violence in Manipur, where an ongoing violence is happening, and the government is almost invisible there; they are not doing anything. I extend the invisibility—a place that is constantly being ignored and violated by the government.

But I must say, I don’t understand politics. As a human being and as a citizen, I witness some unfair things happening every day. I have the right to talk about it and to say something. I feel traumatised by the violence around us. I return to my studio, I cannot draw a flower. We all are traumatised by some dominant powers. And that is making our behaviour change. And that behaviour change is very important, like how we are acting and reacting to these changes in our body and mind.

Tran Luong

I very much agree with Venka’s statement: “Because the instinct ties back to some sort of radical practice. But radical not in the kind of the political sense, all right, but in terms of a practice.” In the process of improvisation and perception of artists, instinct plays a role in keeping the axis of perception filled with personality and the local context without being eroded or distorted by the dominance of the social trend. The instinct to preserve the dare to speak up, dare to practice and dare to confront. When I was young, I felt I had an automatic mind that if I set out to do something, I would do it. But reality teaches me that it is a dream. I trained, I told you, at the academy, and I dreamed of being a big painter. Amid the war, I was quite successful.

We started a collective to create something more realistic and change the language of art. We were quite successful in the early years of Vietnam’s open door, from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s. We started like an early group of artists who went out of the country, and very early, compared with other artists, we could go out. At that moment, we were controlled tightly, and it was not easy to get an invitation to a democratic country.

But after a while, when we had a free market, I suddenly found that it was quite dangerous. The free market came and changed our lives very quickly. For the first time in Vietnam, a painter had a more luxurious life than other artists, compared to film and theatre, which were still tightly controlled by communists. It was not easy for them to travel and to make something. But the painter was more independent, and it was easy to travel and decide our own future. And not much censorship, cannot follow us.

Around 1995, after extensive travelling, I suddenly found that, oh, the free market does not vitalise (it’s not a vitamin boost) but poison. Because artists were getting corrupted early because the market threw money at the artist, ordering them to paint what they wanted, “oh, this series fits well in the eyes of rich Japanese, please reproduce.” You paint for someone else and not for yourself. I’m proud that I say I’m the first artist in Vietnam to start the movement of rejecting the art markets’ proposition. In 1997, I quit painting to do conceptual performance. I found that the contemporary art form gives me more freedom to break away from censorship.

Also, I started thinking about what you can do to change the environment. As an otherwise self-taught learner and curator, I founded an alternative art space where people can talk freely without fear or self-censorship. I founded a studio in 1998; it can be said to be the first artist-run independent space. After that year, I founded the Hanoi Contemporary Art Centre.

So, my artworks express a very strong voice for politics and freedom even though my work itself deals with building environments for people. Since 2000, I have been working on bringing intellectuals and artists into the field of social development to help change the perspectives of people. I organised overnight field trips for artists to help them learn in real time instead of getting information from the newspaper. But they do not spend real-time learning.

Mithu Sen

We share a similar kind of struggle…

Tran Luong

There was an exhibition in Nanjing Museum, one month before COVID-19 involving a group of Southeast Asian artists. The artists tried to push the issue of the upstream dam construction in the Mekong, right in their centre.5

So I made a performance with a soda bottle filled with live fish in water, and the water flowed through my throat, emphasising—whether fish or human—that we need to survive together. We cannot separate. The fish can survive, and I can because I’m still breathing. So, the live performance really showed the real ecological problem in 20 minutes.

But it takes time to transform a conceptual piece of artwork into a direct message—not violent, not political teaching, but the rest of the fish is political. As you know, Vietnam and China are the ‘red’ fish covered by Maoism. I myself grew up in Maoism.

I made several performance works, very political work, thinking about how to turn it into a message. Since 2013, I have been performing with a hammer, everywhere from Paris to Tokyo. The sound of hammering, in many ways, recalls the return of the violent Russian and Chinese troops.

You know, the idea for a live hammering performance came from a very traditional moment. We have a long history of making gold and silver leaf sheets, which are used to decorate pagodas and the Buddha’s body in Buddhist rituals. Traditionally, people, the middle class, even

5 Tran Luong: “Because the organiser had printed the 9-dash line on the poster and banner of the exhibition, I objected to this incident. After that, the organisers removed the 9-dash line on onsite advertising media but still left it on the museum’s website and thus created quite a loud reaction from Vietnam and internationally. Two days after opening, the censors removed my works from the exhibition [I had three works: a 3-channel video projection, a video documentary, and a live performance]. Three other Vietnamese artists and I had to leave Nanjing immediately and fly back to Vietnam.”

the poor, can buy a bunch of goldleaf for the visiting pagoda. They stick the goldleaf to the Buddha’s body to receive energy from the Buddha. It’s a very strong, delicate, and amazingly peaceful ritual.

I was struck by the sound of Vietnamese people hammering. They hammer to make very delicate objects, to make peace. Then I suddenly found out that hammering can also kill. As I grew up, I discovered that hammering can also kill. Then, I created the work that I have made until now. I perform everywhere in the world, in almost 26 cities. It became a film montage, Coc Cach. This is how I adapt the artwork to my history and my life.

In 2007, I was arrested in front of the Mao portrait in Tiananmen Square, wearing a suit and hammering away. My work became significant, and somehow, my works became political just like that. The undercover police inside the Square came, and they stopped me. I tell them I did not dirty the ground; I’m an immigrant from far away. They thought I was Chinese, because it was 1 October (their national republic day), very big crowd. So I did it, and just 15 minutes later, the crowd was in front of me, and suddenly, someone, a big guy, undercover, held my hand, and he talked to me like a dog barking; I didn’t understand.

And I say I’m Vietnamese, I’m foreigner.

He just kept on, picked up the internal phone, and I realised he was police. A group of them, also undercover, came and made the audience go away by covering me.

I showed my other video work and said I cannot speak Chinese. They called someone to translate. They took my passport away bring to the police. I stayed three hours in Tiananmen Square, waiting until the vice-general of police of Beijing Station arrived. He was a senior, and his car could come inside the Square. He talked to me directly, “You Vietnamese?” He knows Vietnam and China [in] very strong conflict, I said yes. “Are you gonna perform more? I say no.” He said, “If you keep performing, I use the rule.” I reply, “Passport?” And he says “Don’t be silly, don’t do anything.” Luckily, someone filmed it from far away and the work in some way shows the 2007 relationship between Vietnam and China.

Huy Nguyen

So that is not so strict like North Korea. First of all, if you were in the NK, you would not be here.

Venka Purushothaman

I’m just interested in your own space, Huy, as to how you negotiate that tension. You are trained in Kyoto, and the Japanese lens of looking at tensions is different. How do they then deal with kind of negotiated space? Has it helped you sharpen your own space, right? Because your Vietnamese experience is quite distinctive from the way the Japanese mind trains you to think. I am aware that the Japanese are well-trained in disaster management, and each community responds quite distinctively to environmental challenges.

Huy Nguyen

Actually, it is in the education system and also in the family training system, which is passed on from generation to generation.

When I was the student in Japan, I thought site training (or learning about a space) from the beginning was important to everyone, whether you were working or just visiting Japan. These kinds of training provide you knowledge on how to cope with nature and manmade disasters. Because Japan is a country that experiences many kinds of disasters, the most hazardous quite frequently are earthquakes and tsunamis. That’s why the children are trained in elementary school about safe spaces to avoid the risks and how to respond to earthquakes and tsunamis. My two children, born in Japan, were trained in elementary school. Another system is training in the community; the Japanese train each other. They document the historical information of the disaster in their own communities and put it on the wall, put it in the notice on the wall. For example, every year, the level of the water since a tsunami is marked to remind newcomers to the next generation that the place has experienced a disaster. They apply technology for weather prediction and every citizen use it. They also have to comply with a law that when an earthquake, tsunami or typhoon happens, every telpatrichalevision must turn on live broadcasts for the reporting of the condition of the disaster.

If you make a comparison with Vietnam, it’s totally different. I still remember in 2020, there were prolonged flood conditions in central Vietnam. It was prolonged for 20 days and is not always in the same condition; it always changes. For example, in the beginning, there was a flood in Huế, the next day in the next province in Quảng Trị, and another day in Quang Binh province. But there is less of forecast news on television, less of warning notices to people.

Then, I started providing detailed information to people in the area about a very big flood coming into that area because I had data, both international and local. From that time, many people started to follow me because of the lack of information from national television. I posted on Facebook a story of what happens when a disaster happens in Japan, what television does. After that, many television stations in Vietnam changed their policy to talk live about disaster. They tried to invite experts from the meteorological centre to talk about the typhoon. I laughed. Okay, at least I have made some changes.

Tran Luong

They now make the reporter go to the site, which they never did before.

Milenko Prvački

It’s a very specific controlled environment, politically controlled environment. And they will justify like, oh we don’t want to disturb people, you know. But usually, it’s tragic because they are not informed. It’s not a Vietnamese syndrome, many countries have this problem.

Huy Nguyen

It puts up the space for political change.

Venka Purushothaman

But I think it also comes back to the idea of providing everyone early warning, and it comes back to my earlier point about instinct. We are always responding to some sort of an early warning because that’s something that artists have learnt in some ways. Because of your own personal transformation through your practice and situated experience in various environments, you have an intuition something might happen. There’s an early warning radar within you.

Tran Luong

The intuition about the possibility of early warning is real. But it also depends on the conditions and luck. That’s why I look for opportunities to organise hands-on projects and field trips for artists. I recall the artist field trip I organised in 2006 to see and experience inland Vietnam and its changes and challenges. Artists were to create work that responded to the experience. If they follow information that exists, it is propaganda, and their artwork is wrong. So they must find out for themselves. Since then, I have seen many artists’ work—not just only the voice and the message—becoming more independent and more real. I believe we build good contemporary artists. I’m very proud and very successful with that.

So this year and last year, in Project of Song Foundation in collaboration with the APD Centre, I sent nine young artists/activists on a field trip; some of them went to a mangrove tree forest in Vinh Chau town, Soc Trang province and some went to a dry forest in Ninh Thuan province, south central region of Vietnam. And I brought three of them to Village 3, Tra Linh commune, Bac Tra My district, and Lang Loan village, Tra Cang commune, Nam Tra My district, Quang Nam province, a central region of Vietnam , where we have a finished project. For two weeks, we organised a conference about our social development project. In five years, we would have built two villages, replacing where they have a problem with the mountain landslide. The villages will as they have better climate conditions, electricity, etc, and people return back to work and live. Now, I have a specific programme for rebuilding a traditional community house, which disappeared during the Vietnam War.

Venka Purushothaman

What you describe is a particular feature in Southeast Asia, where that kind of collectivism starts happening in the artists’ community first with a careful study of materials.

Tran Luong

Yes, nowadays, there is more material and more realistic art, and it is a massive turn in art. But it may promote the wrong future: working as a social developer in general without understanding the people and their communities.

Mithu Sen

Like when you specifically mention how instinctively artists assume or predict the future, and in terms of his or her work, how they take a position to change that own practice.

Around 2007, I was starting my own career and I was suddenly very popular in the art market, the West mostly. It’s always the exotic we are selling outside. And that is a trap.

I remember when I was in New York in 2006, there were a lot of works and solo shows happening, and within six months, my own artwork was prized five to six times more. I was very upset, and you know, I asked my gallery what the reason was. And they tried to say I’m very talented, and I should do my work, and they take care of the market. Of course, suddenly, in one year, you can buy a house.

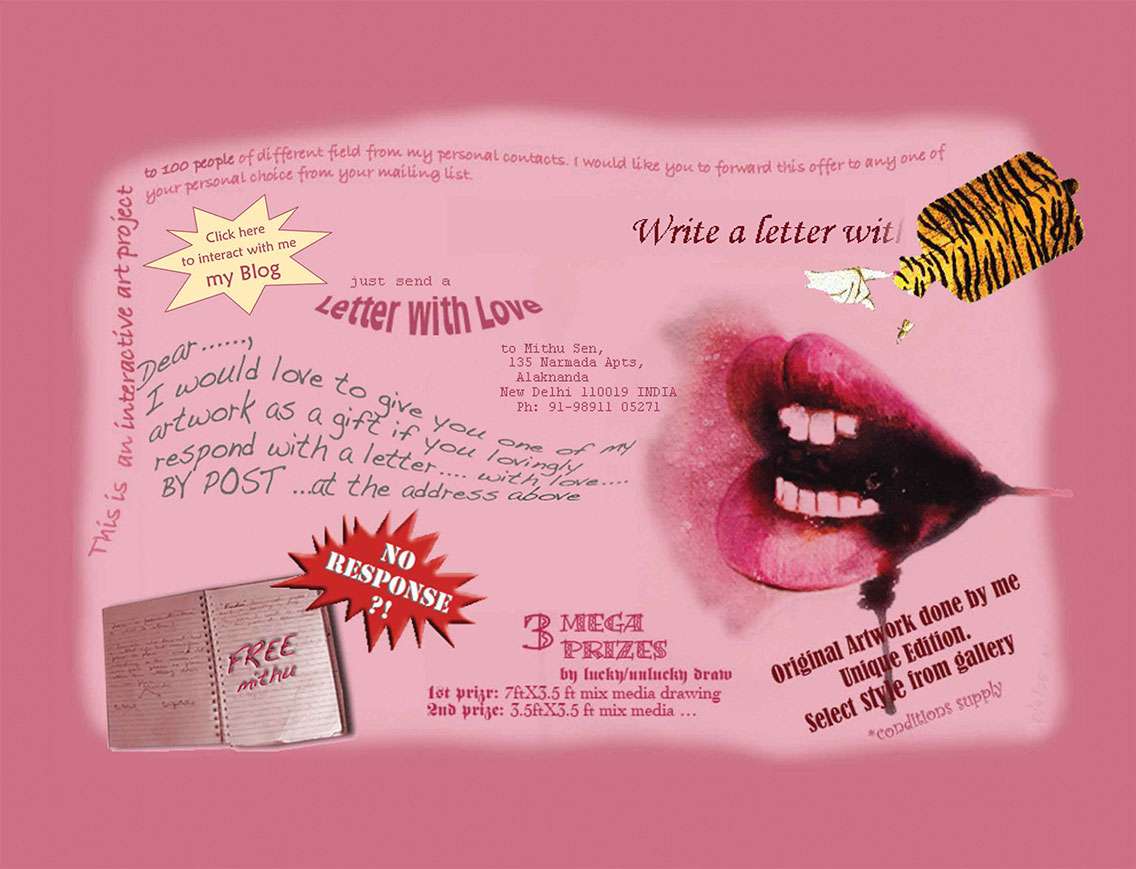

I was in extreme fear and nervous. I said no, and I had to deal with the market in some way. So I launched a website called FreeMithu (https://freemithu.mithusen.com/), putting up 20 works at $1000 each every year. I started giving people free artworks, with conditions such as engaging the community all over the world. It’s free or it’s gifted a gift, you know what’s the politics inside the gift. It’s very interesting. So the whole idea of gift giving, because nothing is free, you know. And to also encounter the market. So if I make 40 works, so 40,000 dollars I earn in a year, but in case 10 works are going without the market, this 40,000 is becoming 30,000. So that was my very romantic way of nurturing or manipulating the market and subverting it.

I’m still doing this—it’s been 16 years now. It was one thing to create a community that wants to really engage in art without going through the market.

Last seven or eight years, I have been doing another project to address censorship. I started creating a legal paper for the government for my artwork, stating that I was declaring why I was making this work. So contractually, I declared all my object-based, material-based artworks as by-products. So this is like started in 2017. Right now I’m working on declaration number 26. So, all my works are by-products, and the rest of the process is my work, which is never executed in one form that the market can handle.

I also use a lot of different mediums like QR codes as my artwork, so that people scan and get to the back-end of each QR code. So, even if they own the QR code, the art owner, does not own the fixed back-end—which is rather unpredictably and randomly changing.

In 2007-08, I did a work on homosexuality called Black Candy (Iforgotmypenisathome). It was highly appreciated at that time, but later, with the change of government and censorship rules in 2019, two of the works from that season I wanted to share were not allowed as the government did not want to hurt sentiments because it had violence and nudity.

I took it as a kind of provocation; I blackened my work, which was originally mostly white, now overdrawn with beautiful, non-controversial images. When I displayed that work, I put a very small before and after photograph of the work (which people almost overlooked) as a declaration asking what kind of inappropriateness in that work made me be self-censored.

Challenging the market, the whole capitalist form of marketing, to deconstruct and kind of breaking is a form of ‘Un’. Un world, so Un-ing that kind of construct, that mythical construct that is in everything. Then, we create an alternative way of sabotaging and then reaching. So as an artist that way, that instinctual kind of function in our system happens, and then immediately we take that call.

Recently, in Dubai, they stopped (censored) me because I screamed “ceasefire!” I was performing a work speaking in a non-language about peace and healing. They said I could not do anything controversial. Even in the Middle East, in a place like Dubai, I cannot be pro-Palestine.

So, I always try to play different roles as an artist around the globe: in my country or outside. This gives space for some kind of experimentation and radicalism. If I am drawing strong erotica and sexualised images, I am deemed a “brave, feminist artist in town.” But they don’t want to see that feminist act where I’m also trying to subvert the market economy by freemithu project or artist declarations. They don’t want to see my feminism there. This kind of patriarchal format that makes artists or defines the identity of an artist is very interesting.t So it’s like my identity in India will be one kind, and in America, it is another type, and in Japan, it is another type. So it’s very interesting to confront different cultures and see how I am looked. For there is one kind of format for ‘Global South’ women artists—expected and projected. A particular range of issue-based practices by women artists are mostly celebrated and controlled by the invisible mainstream West.

FreeMithu 2007–

Freemithu is an ongoing web-based interactive project that started in early 2007

https://freemithu.mithusen.com/

Apolitically Black

2007–2019

mixed media on paper

diptych

152.4 x 121.9 cm each

Courtesy of artist

Venka Purushothaman

I find it interesting that what we call the marketplace today is quite distinctive in the sense that the options are there for the artist to choose different kinds of personas that they might want to take and play with and change with. And that’s something that’s very unique, and the marketplace also has its own control measures on how you function, because we can talk about political systems, but then there’s a marketplace, which is the free market economy, where your works travel to.

Tran Luong

No secret between the politician and the market runner! We have to know how to deal with it.

Venka Purushothaman

The marketplace has always been called the free market economy, which is outside of politics and government control. But governments have also discovered that the marketplace has become a very effective instrument of governmentality. Art marketplaces promote cultural signifiers of countries.

But I think an important part of the theme that’s emerging is how, through your own practice, you build resilient communities both for artists and the community at large. As for artists, whether you’re helping communities realise the weather patterns that affect their lives or enabling artists to understand the weather patterns of the art market is key to operating outside received systems of patriarchal, colonial and historical traps.

Tran Luong

I am concerned about how to see the potential way of working, understanding, and reading in the current world – to be sensitive enough, understand and respond to the ‘weather’ of the market controlled by the forces of self-interest behind it. The artist community and people in general need to reactivate the biological recognition system, which is the senses that have been blunted in the context of rapid and negative changes in the natural and social environment. One of the problems I see is that when we interpret things, our idea is to understand. However, we put too much weight on seeing and hearing to determine our understanding. We are not using our senses of smell, touch, and taste (our tongues are losing). Past ten years, I have been looking at how we maintain our senses or mystic sense or are we losing more than 100 senses?

In my mentoring classes, I try to raise awareness between artists and poor people in the villages at a human level so that we are not desensitised to the environment because of technology. We are not sensitive to tasting fruits anymore. We let our skin not be sensitive to the weather, not because of the temperature but humidity. It says a lot about our senses.

Huy Nguyen

Talking about the sense, just a brief story to share. When I worked in Japan, we had one group studying mythological (traditional) ways as to what we do, how we change ourselves, and change to each other.

Once per month, at least one day per month, we go to the beach of Kobe. Then, we have three ways of measuring the temperature and wind. One is to use the traditional, it’s not the very old tools, for example, temperature measure. That’s the first tool. Another tool is use the electricity sensor. The third one is a human sensor, that you can stand outside for five minutes and then record the temperature into a notice, and then make some comparison with the sense from the skin and from the old tools and also the modern tool. In this way, you observe and cast a sense around their surroundings. It is a good way to connect people to the environment and nature.

The Japanese system does train our body to acclimatise to change through rituals, as the human body has a sense of adapting to the weather and connecting with nature on its own through layers of material. It builds resilience.

Resilient Communities

Venka Purushothaman

The idea of resilient communities seems to be present in all your comments. How do we imagine those communities supporting each other and learning from each other? What does that mean to you, right? I’m just kind of interested in hearing your perspective on the role of translation and translatability in communities. I think translation is a big part of some of the things that you do—such as social development, public education and dismantling the power of language system—continuously problematising issues and spaces.

Huy Nguyen

In extreme events in Vietnam, community-based disasters help build social capital amongst the people and people in the same places. In the past, we have a very strong culture of helping each other. For example, during flood relief efforts, neighbours help each other by sharing safe spaces such as the second floor of their house. The mood to help build social capital. We can be proud to say that the social capital among the commune is that the villagers are very strong in Vietnam. However, today, people tend to be closed up because of safety.

Venka Purushothaman

Why do you think that’s happened?

Huy Nguyen

Before, people did not have good things inside their houses. Now, they have televisions, computers, and cell phones. They have something they want to protect. Trust is limited. This weakens the connection with neighbours. This is visible as the speed of development forces people to stay closed in, not open to others. This affects the resilience of communities. And that’s my observation.

Milenko Prvački

Could be. I have experienced living in Romania. It’s not about protecting what you have, but people don’t trust you because you don’t know who’s spying or who’s in control.

Mithu Sen

This is real. This thing about door/window grills, is it for the neighbours, or is it just for me? I can trust my neighbour, but I may not know who is passing by. So, it’s not like my neighbour; maybe I still trust them, but I still put the grills to protect myself from some other circumstances or some animals come, like the cows or the dogs, stray dogs. So, it can also be like that, but it is also like distrusting your neighbour.

Tran Luong

There is also another problem because of migration. People move, and with new people next to you, trust is less.

Mithu Sen

But I think because if we talk about community and trust, we may have to think beyond the physical location because your community may not always be one in your immediate surroundings. We develop our own communities based on trust, and they could be in different parts of the world or virtual.

A kind of trust emerged within a community, believing just in art.

As I mentioned earlier, moving from Kolkata to New Delhi and then to Glasgow—the anglophonic colonial atmosphere and its hierarchy and elitism made me numb from continuing to write Bengali poetry. I stopped writing for about 10 years. I went into silence. I wanted to understand true empathetic human communication—like how people communicate when you feel humiliated, and how we can overcome that too, you know, develop that compassion and empathy between us to create a community. During the 10 years of my complete silence from Bengali poetry I was practising my visual art, experimenting in this space language, its construct and myth. India has many languages, and dominant languages suppress many, many native languages. Similarly, around the world dominant/coloniser’s languages killed/suppressed others. I have experienced travelling around the world facing unknown languages and cultures. As an artist, as an experimental material self, I find myself throwing myself into vulnerable situations where I don’t understand Portuguese, Japanese or Chinese but discovered a mode of communication.

My confidence was building with something that was there, where I could still communicate and survive. With that kind of belief, I started performing, I call it ‘perform’, but I think it’s like my life, I do the gibberish non-language performance, to deconstruct all kinds of languages. Not to build another language. That is how I think, on a very conceptual level, here, the ‘weathering’ comes in. How you weather yourself, you know, how with your body, with your language, with your religion, everything. However, that also brings a lot of victimhood and polarisation.

Milenko Prvački

Polarisation is killing. But technological devices are helping. Japanese and Chinese almost don’t speak English. Last year, I was shocked at how they communicate. They have these devices to communicate with everyone.

Mithu Sen

The advancement of science and technology has made a space for different kinds of communities all over the world. But there is also instinct.

Venka Purushothaman

Community is built around language and trust. And just listening to what is being said, I think one of the key things is today we have a trust deficit, you know we don’t trust systems, governments, neighbours—we don’t trust ourselves for we may be vulnerable. So, I’m wondering if, more than trust, we should focus on reliability. Can I rely on someone to help me? It might not be my neighbour, but my global artist community, which might be a reliable community. Whether I trust them or not could be a different thing, but I could rely on them to help me if something is difficult.

Mithu Sen

Yes, it is possible.

Venka Purushothaman

Reliability does bring us back to some sort of social or associated engagement with various people. Relying on someone will allow us to transcend the translation and language issues and find a common purpose. In sociological terms, this is called associational relationships. We always build relationships associated with a purpose outside of the formal kinship systems.

Tran Luong

When I jump out of my ivory tower as an artist, I realise that you have to read different people and situations and understand the disconnect between my life in an artist community. When you live in your own artistic community, everything is quite easy and tolerated. You even fight with each other. That’s why I try and mentor artists to work in different spaces. It’s a kind of self-learning and getting more experienced by understanding others.

In working with communities in social development projects, first, we have to work to create trust. Secondly, co-design the way we make trust. If we do not ask them, give them a voice, or give them ideas, there will be no trust. I work closely with the village/province leaders and let their elders choose the land on which we will design and build. After many challenges, culturally specific concerns and government regulations, the people love the village we built for them, and other villagers come to stay here.

Milenko Prvački

Villages in Serbia are similar. When someone is not speaking at their level, they consider you a philosopher, which has a negative connotation. They hate intellectuals and only engage with people who can do something, convince and speak their language.

Tran Luong

Yeah, actually, they really hate us if we do not really like them.

Mithu Sen

Experience the real side of real people! It’s great that you already developed your organisation.

Tran Luong

Self-taught!

Mithu Sen

Your personal initiative in building this organisation and developing this kind of project is great.

Venka Purushothaman

One of the unifying themes that’s emerging for me is, how do we then, in looking into the future, look at artist education in different ways, just like the way you bring artists to work with the communities.

Tran Luong

Yes, education should change.

Venka Purushothaman

Right, it’s changing quite dramatically because artists’ education is also no longer about that isolation sitting in that studio, but by being located in those very communities—doing, making and living with their communities. So, it’s organic, with no separation between the environmentalist, the farmer, the artist. They are all building themselves into the way they actually think, do and want to live.

Mithu Sen

Contemporary art should be rethought completely beyond the object-based experience; it should be organic, and artists should not think so much about the longevity of their art and its archival material.

Tran Luong

Sorry for interrupting you, but if we look beyond, everything needs to change altogether. We have to change the rules. Museum structures are already backwards today. Art universities are no more fun. There should be less permanent faculty and more invited artists to teach. The class should be outside, not in the auditorium anymore.

Mithu Sen

Yes, you know, in Shantiniketan, where I studied, it was just like that.

It cannot happen overnight but organically. The speed of digital technology works for the young generation. A four-year-old can operate and show you everything. It is key to think about how our body and mind develop. Today, we seem to be occupied with art with a temporary, short-lived memory. The perception of perfection is changing.

Milenko Prvački

For 50 years, I did not care, but now, in my 70s, I am archiving because nothing exists in memory because of the speed of technology. I must say that all art is conditioned by technology. First, humans discovered they could paint caves with terracotta; it was an invention. It only took 20,000 years. After that, 300 years ago they found the fresco wall. And then oil, then photography…

Tran Luong

It’s very much based on scientific discovery of materials.

Milenko Prvački

Technology conditions a lot of things, especially art.

Mithu Sen

Are we only thinking about ourselves, protecting our past and archiving our history?… I’m just thinking radically.

Milenko Prvački

I know you are talking about choosing, choosing methods that are valid.

Huy Nguyen

Can I say something? We talked a lot about community engagement. When I worked in Japan, I had a small room for living on a floor with more than 10 rooms. No one knew each other. Every morning, we say Konnichiwa (hello) to people. And then when we meet each other nightly, we just say Konbanwa (good evening), no further communication. And that’s all we say to each other, even though we live under the same roof. Not because of language but because of culture. The Japanese have a kind of value—the best gift that you can give to someone is to not disturb them.

I have a friend, two friends actually, twin activists who do art: Le brothers, I don’t know if you know of them [question to Tran Luong]. When I visit one of them in Hue city, he is doing some performance painting. I ask, “What are you doing?” and he says, “I’m doing a performance.” Performance for him means he invites his neighbour to join him. For the project named In the Forest I saw him put oil over a wall and doors and invite some people to drop more oil.

And then I asked, “What are you doing?” He answers me, “I’m asking the tree how old it is, and I invite people also to ask the tree.” But actually, it’s not the tree, the door is made from wood, and that is the way he communicates with the neighbour, with a friend. Everyone can join the art activity. Art is not expensive, art is not that difficult to understand. Art is, you know, familiar and open—so I think.

Milenko Prvački

And that’s why public art, or community art, are good, because they are open. You don’t need money to see public art.

Huy Nguyen

No tickets, no access rights issues.

Weather Forecast

Venka Purushothaman

I want to get everyone’s weather forecast. What’s your forecast for the future?

Tran Luong

To fit into a world that is quickly changing, we as artists should not be quick at change, but we should keep our own speed. If we keep it slow enough, we can see things differently, and we can see things clearly than we stay on the train. Because if we stay on the same train, you know the vision of the landscape all the same.

But the solution, I think, and I practice this, is being site-specific. As things change, we as a society are destroying the environment. We should change our social structure. I really like that we talk about climate change, changing the environment—culture helps to change. So, being site-specific is important.

And how can it be site-specific? The modern is already growing, and artists today should take on the role of social developers. Artists need more knowledge, more practical works, more engagement and more crossing of continental borders. But if you look back to history, artists travel a lot rather than staying in the bamboo jungle. Cross-continental travel is a better thing to do, and I think many will travel in search of a better model of art practice. That is my forecast.

Mithu Sen

In my own way, which will be poetic and political, creating a speculative fictional kind of imaginative space is needed. I believe that something poetic will always be understood in the future. If I can create something through the medium of poetry—not in the sense of language or taste—but indulge in poetic freedom, speculating something like whether it’s a river or a forest or a human being having like a horn in their forehead will be very imaginative. A very strong experimental radical speculation that can create a kind of sense of fear, and also a sense of awareness, that as an artist, I can bring to that imaginative space.

Huy Nguyen

The weather changes hourly, hour by hour, and lifestyle as well. Movement is always about change. The central question is whether we adapt to the change or keep to our original values. So important in our work, I think, to try and keep values traditional, but still adapt to the movement, to the transition. Lifestyles are changing, technology will always develop, and we cannot even imagine what it will be. But some core values will still be there. We should try to adapt to protect our core values.

Milenko Prvački

I think that we need solidarity, altogether. It’s still weather, you are a scientist, you are a community-based activist, you are a poet, I’m…old. You know, but what I want to say is we need to unify in this. It shouldn’t be a political agenda to save this planet.

Venka Purushothaman

We all can contribute in our own way. I can’t do what he does, and he can’t do what I do, but we can build together. That’s all.

That is a wonderful closing because I think all of you really summarised some significant work. I totally agree that to move forward, the weather of our era has to be built on solidarity, core values, being poetic and changing at our pace.

We need each other’s help and to learn from each other. But to take it further, even in solidarity, we need a renewed commitment to our core values and our purpose. It’s not about saying what the right value is or not, but how we want to define our values at that moment.

And those values have to be underpinned by what is our emerging politics or philosophy that’s coming through. So, you talked about the new philosophy that is going to shape this generation because we are all in a moment where everyone is disagreeing with everything that happened in the 20th century. We are all in that moment of flux or turbulent weather, correct? I think that philosophy has to be wayfinding space for self-expression—finding meaning through different forms.

A lot of the answers are also not so much about the big picture as opposed to what we do onsite, in a site-specific location. So situatedness, and I think this is where it’s going to become very critical, because we need to be situated and, from that situation, see the world. But the point of it is, being situated, we can develop a point of view. through my community. And I think that’s what kind of beautifully came through these two days of conversations—I’ve learnt a lot, listening.

Mithu, Huy, Milenko, Venka and Tran at dialogue at APD Center. Photo: Sureni Salgadoe

Courtesy of LASALLE College of the Arts