It is the start of the year 2050. The months have melted away and the seasons seep into one another, liquid, languid. Time’s passage is guided solely by the cycles of the sun and moon, the Gregorian days of waged time a blurry memory of a past long gone. Back in the Old World, people learnt to manipulate time with the mechanics of manmade devices. They made clocks that could shift time back and forth with the turn of temperate seasons. An hour more to the working day, even as the daylight hours shortened; one less hour of sleep, even as the nights grew longer.

Here on the equator in the historied Riau-Lingga Archipelago, where the present-day Singapore state sits, time has always been consistent. Day and night will again remain at equilibrium in the year 2050, especially during the Monsoon Equinox when the Earth’s rotation is at zero degrees both latitudinally and longitudinally. The days will start at seven when the sun rises, and nights will start at seven again when the moon ascends. The only period in history when equatorial time was out of joint was when the ones who came from the Old World occupied these lands, and the tumultuous years after their exit, when the then-newly formed equatorial nation states grappled with the aftermath of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), another Old World mechanism that used the longitudinal Prime Meridian at 51° 28’ 38’’ N as the false ground zero of all-world time. Up until 1984, the position of Greenwich north of the equator was treated as the centre to which all other places on Earth had to coordinate their time. When rulership over the archipelagos and highlands running along the equator got scrambled up by conquest, there remained a period of confusion even after the occupying forces left, despite the revolutionary fervour of decolonisation, as to how to align time to the false centre of Greenwich. As an example, until 1941, Malayan Time was standardised with the Straits Settlements across all its lands and waters, to GMT +07:30. After the Malayan Federation split, there was more confusion to come, as Malaysia shifted its Old World-inherited clocks forward to +08:00 in 1981, and its ex-Federation counterpart Singapore chose to follow suit to match, for the sake of retaining business and travel relations across its new divisions.

Now, time is the same everywhere, cycling through the seven seasons all across the world. Many expect that at this year’s Conference of the Parties (COP) during the season of White Dew, it will be announced that the net-zero targets for carbon emissions, as set out in the Paris Agreement in 2015, have miraculously been met.

STEVE (Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement) and the Milky Way at Childs Lake, Manitoba, Canada, 2018. The picture is a

composite of 11 images stitched together. Photo by Krista Tinder, courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Centre/Flickr.

Yet too much damage has already been wrought, and some changes remain irreversible, like the disappearance of the season named winter. Now, even at the poles of the Earth, a new year starts when the monsoon surges cause widespread, continuous, moderate to heavy rain, at times with 25–35km/h winds in the first half of the season, and rapid development of afternoon and early evening showers. There are no more glaciers or sea ice left on the Earth’s surface, only in the relics of deep freezers. As the last ancient ice sheet melted away in 2049, the polar vortex no longer remains polar, inciting a combination of warming air and ocean temperatures from the poles to the equator, and frequent occurrences of geomagnetic storms along the equatorial belt. Boreas (north wind) and Auster (south wind) are also no longer, having slowly been absorbed into the monsoon drifts of the equator since 2016, when the Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement (STEVE) phenomenon was first officially discovered. Instead of the Auroras Borealis and Australis, namesakes of the Grecian north and south winds, STEVE has been erupting across the sky every night during the Monsoon Equinox, a hazy enchantment of magenta amid the constant rain and warm winds of the season, a phenomenon which we can expect to continue seeing in 2050 as well. After the Monsoon Equinox, comes the season of Lalang Fires.1 Fierce winds are expected to plough through again this Lalang Fire season, when the warm monsoon winds turn dry and unpredictable, sparking grass fires across the island. It starts with the slow crepitation from burning weeds, with sound travelling fast towards the city centre. As always, it will be a busy season full of mayhem for the local Civil Defence Force, but they have maintained a strong track record of being reliable first responders to crises of varying natures since 1948, when a record-breaking heatwave sparked twenty-two fires across just four days. Investigations found that the cause of the outbreaks were unattended joss sticks at cemeteries during the Qingming Festival, a Taoist day of offerings to the spirits of deceased ancestors which historically took place 106 days after the Winter Solstice. Since the early 2010s, after the enactment of the New Burial Policy in 1998 that cited land scarcity as a reason to impose a fifteen-year term on burial grounds, Qingming rites began to migrate to temple columbariums as the dead were exhumed from the ground, and cremated or reinterred into crypts instead, depending on one’s religious beliefs. In 2007, the Crypt Burial System was introduced alongside the New Burial Policy, which saw the mass transference of Muslim places of rest to a grid-like cemetery in Choa Chu Kang, and the gradual disappearance of multifaith burial sites.

These days, Qingming is observed throughout the season, but temple managements have banned unattended fires in rites and rituals. They have also reduced the number of joss sticks that can be used for prayer (Ng, 2023). The institutionalisation of such practices has not meant their acceptance from devotees. The Force responded quickly and effectively to the 1948 fires, though, and have continued to do so since. Although Qingming-related grassfire outbreaks have dwindled over the years, it is predicted that the 2050 season of the Lalang Fires will not be any easier to manage than previous years, as dry winds blow across the island wilder than ever, at high speeds. For better or for worse, it has been remarked that “‘crisis’ is the metier of the Singaporean state.”2 Crisis conjures chaos, unmanageable and unruly. Crisis invokes control, as in damage control, a calculated managerial impulse enforced en masse. Chaos evokes anarchy, as in calls to action, the emergence of self-organised methods of living together in a more-than-human world. These first fifty years of the Anthropocene have oscillated wildly between crisis and chaos, a long, difficult balancing act between impulses to control, and grassroots organisational movements.

After the Lalang Fires comes the Awakening of Insects. The lingering heat of the grassfires warms the soil; the Earth becomes humid as hot air rises from the heated ground. Meanwhile, the hot humid air from the north is strong and creates frequent winds. Arising as a countermovement to the preventative measures against the grassfires, the Awakening of Insects has become a season of vernacular, syncretic ceremonies, when bonfires are lit in open fields to collectively mourn the losses of the last fifty years, while awakening new cycles of life. Unlike during the season of Lalang Fires, though the winds fan the flames of the ceremonial bonfires that are held during this season to rouse the insects from their slumber, humidity swallows the fires again by nightfall, and no major damage is expected.

As the earth warms, various species of insects, non-human and post-human, awaken from hibernation and rise from the soil. They swarm the skies, unhindered by the skyscrapers that used to dominate the Singapore horizon.

Image of a swarm of insects over an open field, created with Open AI DALL-E 3 text-to-image generation software.

Courtesy the author.

In murmurations numbering in the thousands, they begin their migratory journeys across the world, scattering lifegiving pollen and seeds along the way. Across the climate discourse that has developed since the start of the twenty-first century, some words often appear as suffixes: crisis and control, alongside others like action, adaptation, displacement, justice, migration, mitigation, reparations. These climate-related syntaxes generated a paradox of concurrent yet unsynchronised scenarios, where the consequences of centuries of anthropogenic climate change created extreme inequity throughout the world. Small islands in warming and rising seas were the first to initiate a global call to action, yet many of them were the first to suffer the consequences. The Paris Agreement has been fulfilled, but not without sacrifices and losses.

The Awakening of Insects is a time for mourning, while looking ahead. Many believe that the government’s 30 by 30 initiative, which aimed to achieve 30% of local food growth by 2030, failed because of their lack of support to preserve local and indigenous fishing and foraging techniques. Instead, an expensive, techno-engineering development programme was pursued with the singular goal of increasing agri- and aquacultural yields. In the process, open-air, land-based farms and open-sea fishing were forcibly replacing with confined, microclimatic solutions.

The word ‘microclimate’ implies the ability to control or manipulate ‘climate’ into something scalable and manageable, which has been proven to be an impossible task, though not for a lack of trying especially in the case of Singapore. Entrenched as it is in a long history of protectionism and safeguarding national interest, this logic of control fits neatly into its founding narrative of survival, that propagated the creation myth of the formation of the modern nation state. Early efforts to terraform the island’s natural landscape into a microclimate optimised for maximum productivity evidence this survival-of-the-fittest mindset. The narrative of climate control continued for a long time to undergird the development of the island-state as an ongoing project of constant monitoring, upgrading, and optimisation in the interest of microclimatic survival and flourishing.

But it was the park’s microclimate that he was most concerned about. Unceremoniously taking leave of the parks’ officials, he and Mrs Lee took an unscheduled walk along the Esplanade, with security officers and reporters hovering. Walking through the Anderson Bridge tunnel and past Victoria Theatre, they stopped by the Singapore River, near the statue of Stamford Raffles. There, the prime minister gave reporters his verdict. The pavement was so broad, he said, that the trees, even when fully grown, would leave large areas exposed to the sun. He noted that although the sun had nearly set, one could feel the heat through the soles of one’s shoes. He squatted suddenly and placed a palm inches off the ground. He could sense the heat radiating from the pavement, he said.

—Cherian George

Air-Conditioned Nation: Revisited, 20203

“Think of Singapore instead as the Air-Conditioned Nation,” the media scholar Cherian George once suggested, “a society with a unique blend of comfort and central control, where people have mastered their environment, but at the cost of individual autonomy, and at the risk of unsustainability.”4 And indeed, the time of unsustainability arrived, climaxing in the 2030s, heralded by the mass teardown of towering office and housing complexes as they turned from novel urban planning solutions to solve land scarcity, into safety hazards, as natural barriers of protection against strong winds slowly eroded away.

Tall, towering buildings, constructed with modernist materials like steel, glass, concrete and so on, became too heavy to withstand the relentless storms that come with Grain Rain, the season that follows the Awakening of Insects. As the ice sheets melted, sea levels continued to rise, and skyscrapers got torn down block by block in desperate efforts to keep reclaimed lands afloat. Their mass and centre of gravity were too high for the artificial islands on which they were built to remain buoyant amidst the floods that rushed in against the old water-breakers and sea walls. These historic fixtures have been around since the early 1990s, when the government first started mandating that every new reclamation and construction project had to be built to double the height of the expected sea level rise in annual Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates, and vulnerable highways constantly elevated. As more and more stone and cement were added to meet these standards, they started to weigh heavier and heavier on already sinking islands. By the late 2010s, 70% to 80% of Singapore’s coast, both natural and reclaimed, was already lined with hard walls or gradated stone embankments,5 but they could never keep up with the ever-increasing heights of new construction projects.

Inevitably, some islands sank, but for the most part, people have learnt to live with the rising seas. Bamboo rafts have become popular again, for their durability and tensile strength against the strong winds and currents that come with Grain Rain season. Historically celebrated by fishing villages in the coastal areas, Grain Rain marks the start of the fisherfolks’ first voyage of the year. On the first day of the season, marked by the first downpour since the Monsoon Equinox, people would worship the sea and stage sacrifice rites. The custom dates back thousands of years ago when people believed they owed a good harvest to the gods, who protected them from the stormy seas. This period of rainfall is also extremely important for the growth of crops. As the old saying goes, “rain brings up the growth of hundreds of grains.” It’s warmer than ever, but we are coping. There are less office buildings than there were before, as air-conditioning technology for hundreds of floors of square footage became too costly to bear, not with the net-zero target that had to be met.

As the soil absorbs the rainfall of Grain Rain season, the earth warms again with the season of Rising Heat. During this season, the mid-afternoon heat is expected to reach an average maximum of 38 degrees Celsius, which meteorologists hope will be the limit for the next fifty years. Lazy natives, some were called by neocolonial leaders who had adopted or been indoctrinated by Greenwich Mean Time, for seeking shade under generous banyans in the mid-afternoon heat.6 Even then, the elemental forces of the equator proved powerful resistors to the clockwork rhythm of manmade time. When the red-haired ones first landed here, they too could not deal with the heat, and perhaps never learnt to do so. A piece of advice in the Malayan Federation’s local daily Morning Tribune read in 1936, more than a hundred years after their first landing, “If you want to look and feel cool, rearrange your living schedule so that you will not have to hurry and worry so much … Allow yourself time for a brief siesta and a cooling shower …”7

The ‘living schedule’ on the equator (though not quite about a cool, leisurely, and worry-free life), however, was always already in tune with the eddying movements of heat, governed by the cycles of the sun and moon. Workers of the land would rise with the sun while taking breaks in the shade, while fisherfolk who work on floating farms would follow the push and pull of tides, as the moon waxes and wanes. They work this way not out of laziness or indolence, but because they know it makes no sense to work against the weather, or on a time out of joint.

Across the 2010s and early 2020s, construction companies learnt this the hard way when they started losing workers to heat-related accidents, despite groups like the SG Climate Rally (SGCR) warning and advocating heavily against such workers’ violations. Construction entities have since dwindled in influence or transformed into unionised coalitions. The construction boom in Singapore infamously started in 1961, following the notorious Bukit Ho Swee fire that skyrocketed the profile of the then-nascent Housing Developing Board (HDB). The fire, which broke out in the tightly packed and highly flammable kampong squatter settlement of wooden houses in Bukit Ho Swee, rendered some 16,000 people homeless, despite a robust ‘culture of fire’ that existed in kampong settlements, in which local volunteer firefighting squads consisting of unemployed youth and secret society members took turns to patrol the kampongs. The biggest fire yet in Singapore history, outdoing even the 1948 grassfires, it is considered by many as the pivotal moment in the transformation Singapore’s architectural and social landscape, turning unruly urban squalor and ‘inert’ squatter communities into modern, lawful citizens living in planned estates.8

“Looking Cool in Hottest Weather.” The Morning Tribune, 18 August 1936, p.17.

Courtesy National Library Board, Singapore. First cited in an essay by Fiona

Williamson in the chapter “Lalang Fires” in The 2050 Weather Almanac,

ed. Soh Kay Min and Ng Mei Jia, 2024.

Till this day, the cause of the conflagration remains a mystery, though there were whispers during the heated pre-independence years of the early 1960s, that the Bukit Ho Swee fire was a case of arson, sparked by the then-ruling party to declare a state of emergency that would blaze a path straight through the kampongs, so to speak, and clear space to launch their highly-anticipated high-rise public housing model. These rumours were never verified but reveal an enduring fact of public perception and the power of grassroot beliefs. Even as the heat of fire dissipates, the smoke of secrets lingers in the air long after. This season of Rising Heat, the case of the Bukit Ho Swee fire is tabled to be reopened for investigation, as civil society calls for accountability for the numerous heat-related deaths on construction sites force the courts to locate and address the historical root of the problem.

Tan Choo Kuan, Rebuilding Bukit Ho Swee, 1962.

Ink on paper, 37.3 x 27.2 cm. Gift of Ms Tan Teng Teng. Collection of National

Gallery Singapore. Courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore

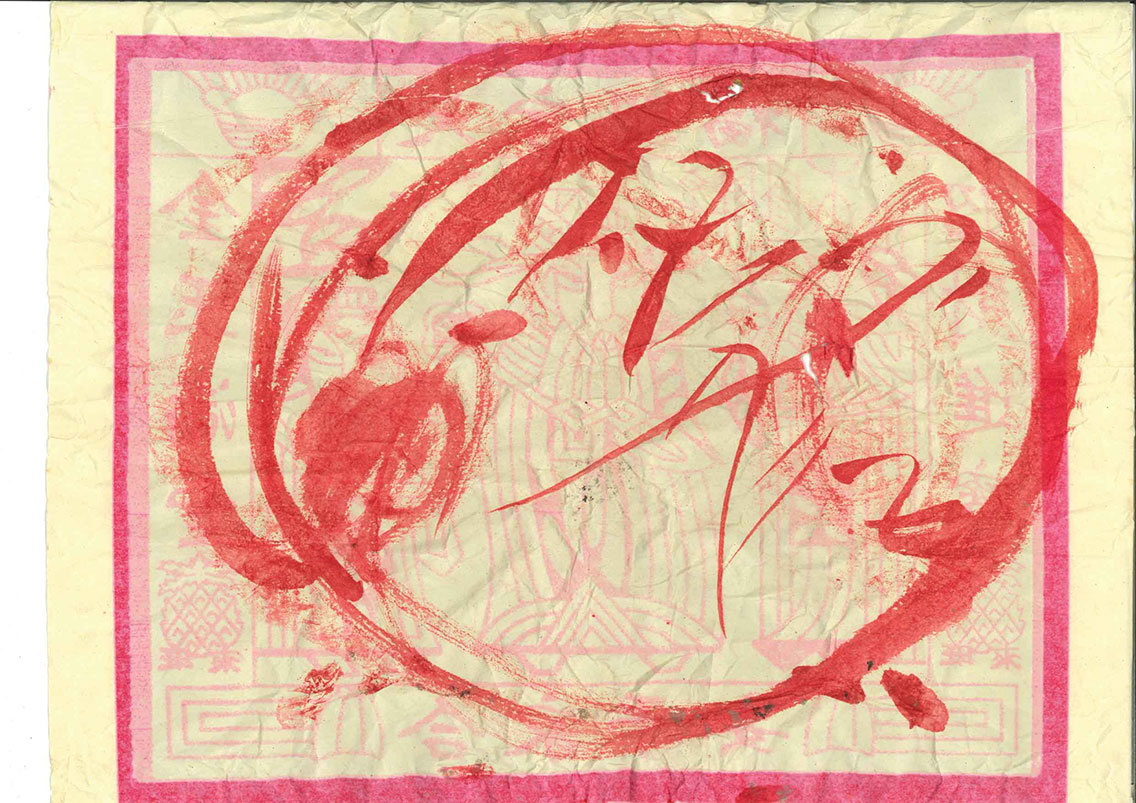

Ink drawing on joss paper by Thunder Marshall Leizhenzi, during a consultation

at Shui Gou Guan Temple, Singapore, on 27 November, 2023.

Courtesy of Shui Gou Guan Temple.

Bolts of lightning illuminate the sky in the season of Sumatra Squalls, as hot afternoons get subsumed by sudden thunderstorms and short-duration showers, and strong wind gusts up to 40–80km/h stir up the seas from the predawn hours until midday. Taoist devotees have long believed that the Thunder Marshall is most active during this season. A leading deity of Heaven’s Department of Thunder, he descends to the mortal realm every two weeks during this season, to commune and provide consul with his congregation, channelling his presence through spirit mediums and ritual performances. The Thunder Marshall’s likeness is said to be that of a bird, and the howling squalls of the season’s early morning wind gusts are believed to be a sign heralding his arrival, alongside booms of thunder that rumble like a drumbeat through the air and in one’s chest. Legend has it that at the bidding of the Heavens, he metes out punishment to both earthly mortals guilty of secret crimes, and evil spirits who have used their knowledge of Taoism to cause harm in the realm of Earth.

Yet the power of the deities resides in the power of belief in their presence. It is based on a dialectical relationship between the spirit and mortal realms. Within the last fifty years, the mortal realm has encountered an unprecedented series of ecological trials, as fires during the hot seasons took away lives and destroyed infrastructure, or lack of rainfall during Grain Rain in some years resulted in poor harvests and hungry ghosts. Belief in the gods waxed and waned, as people wondered if their prayers were being heard at all. As a rare interview with the Thunder Marshall conducted in 2023 showed, however, the deities do not hold any material sway over events of the mortal realm, neither are they capable of controlling the weather.9 Rather, they exist with the cycles of nature as it transforms: the two seasons of fire, Lalang Fires and the Awakening of Insects, used to be one. But as the Thunder Department saw the sincere, continuing need of the people to mourn with open fires, even as temple managements banned the practice, Madame Wind, another deity of the department and a trusted assistant of the Thunder Marshall, turned the dry gusts wet and humid, tamping out the bonfires that would otherwise spread through the island.

Historically, years began with the Winter Solstice. It was the first solar term to emerge in the traditional lunisolar calendar. As the months melted away and winter disappeared, White Dew has become the last season of the year. As the squalls die down and storms abate, an unusual chilly vortex is left to signal the last of the seven seasons. When air-conditioning was still a widely utilised tool of climate control and heat relief, meteorologists struggled to forecast the season of White Dew as its namesake dewy residue, a result of vapours condensing on grass and trees, were spotted all the time instead of just during the morning hours. Since the mass teardown of high-rise buildings lined with vertical columns of air-conditioning units for each household, it has been much easier to recognise the arrival of White Dew.

There was a period when the invention of the air-conditioner was seen as a life-changing technology that changed the lives of people in the tropical regions. This was the time in between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, when the ‘lazy native’ myth had yet to die away. A fabled leader of the time once said, “before air-con, mental concentration and with it the quality of work deteriorated as the day got hotter and more humid… Historically advanced civilisations have flourished in the cooler climates. Now, lifestyles have become comparable to those in temperate zones and civilisation in the tropical zones need no longer lag behind.”10 In the year 2050, however, the coldest season has been lost, and some like the artist Kent Chan (in his videos Future Tropics, 2023; Warm Fronts, 2022; Monsoon Sessions, 2022) even anticipate a complete mono-climatic expansion in the next few hundred years, in which all meridians and parallels will become tropical. This White Dew is expected to be slightly warmer than the last, considering the melting of the last ice sheet in the past year. Along with the possibility of a New Tropics, this issue is expected to be a key point of discussion at the season’s annual Conference of the Parties.

Kent Chan, Future Tropics, 2023, video still. Courtesy the artist.

Acknowledgements

The research for this essay is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Academic Research Fund Tier 2 grant for the project Climate Crisis and Cultural Loss (MOE-T2EP40120-0002).